Mars – God of War

We’re finally into the month of March and Spring is in our sights.

If we were living in ancient Rome, this would have been a very exciting time. Mars’ month, or mensis Martius, was almost entirely taken up with various celebrations to honour the Roman god of War.

The festival of Mars included the Equirria, a horse-racing festival at Rome, and the Tubilustrium, the day when the sacred war trumpets were purified. The festival of Mars also coincided with the Matronalia, the festival of Juno, mother of Mars, to whom prayers were offered. During the latter, husbands gave gifts to their wives, and female slaves were feasted by their masters.

One of the fixtures of the Festival of Mars were the dancing, or leaping, priests of Mars known as the Salii.

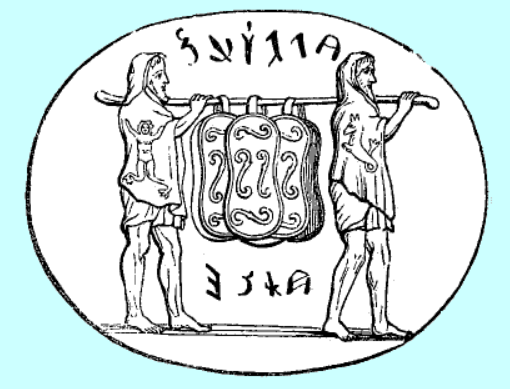

Artist impression of Salii

Throughout the festival, the Salii would process through the streets of Rome wearing military dress and armour, and stop at certain places along the way to perform ritual dances and sing their ancient hymns known as the Carmen Saliare, sung at the beginning (March) and end (October) of the military campaign season. Here is a small fragment:

Sing of him, the father of the gods! Appeal to the God of gods!

When thou thunderest, O God of light, they tremble before thee!

All gods beneath thee have heard thee thunder!

…

but to have acquired all that is spread out

Now the good … of Ceres … or Janus

…

In the Roman state religion, there were no full-time, professional priests. Most were taken from the aristocracy, including the Salii who were supposed to be patricians with both parents still living.

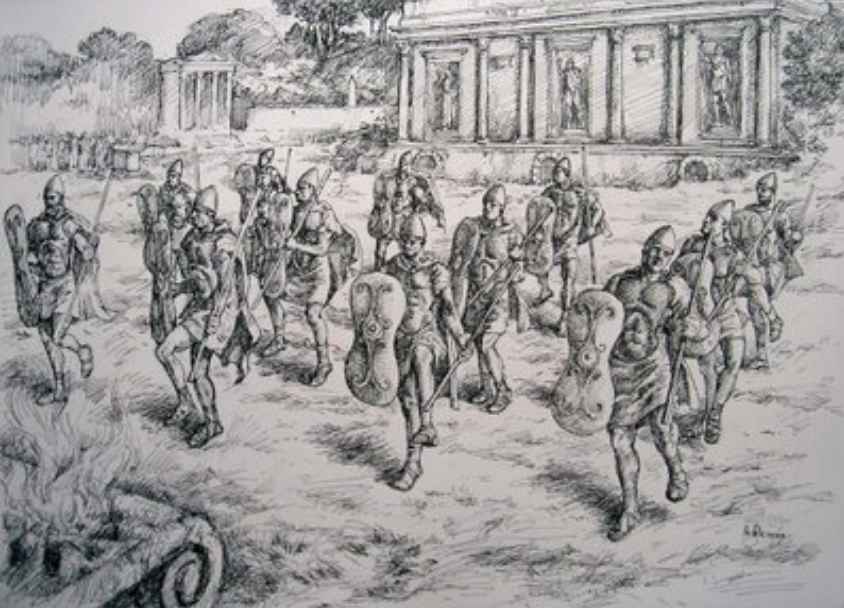

Artist impression of theTemple of Mars Ultor

But where did the order of Salii come from?

Legend has it that Rome’s second king, Numa Pompilius (715 – 673 B.C.) created them in order to protect the sacred shields of Mars, called the ancilia, which the Salii carried in their processions, and which were stored in the Temple of Mars. Dionysius of Halicarnassus relates the legend:

Among the vast number of bucklers [the ancilia] which both the Salii themselves bear and some of their servants carry suspended from rods, they say there is one that fell from heaven and was found in the palace of Numa, though no one had brought it thither and no buckler of that shape had ever before been known among the Italians; and that for both these reasons the Romans concluded that this buckler had been sent by the gods. They add that Numa, desiring that it should be honoured by being carried through the city on holy days by the most distinguished young men and that annual sacrifices should be offered to it, but at the same time being fearful both of the plot of his enemies and of its disappearance by theft, caused many other bucklers to be made resembling the one which fell from heaven, Mamurius, an artificer, having undertaken the work; so that, as a result of the perfect resemblance of the man-made imitations, the shape of the buckler sent by the gods was rendered inconspicuous and difficult to be distinguished by those who might plot to possess themselves of it.

(Dionysius of Halicarnassus; Roman Antiquities)

King Numa instituted twelve Salii to guard the sacred shields and perform the rites for Mars, and his successor, King Tullus Hostilius, is said to have instituted another twelve Salii, bringing the number to twenty-four which became the norm for generations.

Salii carrying the sacred Ancilia

It must have been quite a sight to see these patrician priests dancing through Rome’s streets, carrying the sacred shields while singing, and dancing or leaping before the crowds.

We should remember that this was not some clown-like activity. Mars, war, and the rites to honour both were extremely sacred to the Roman people. When the Salii came into a square, or stood before a temple, I can imagine a hush falling over the people of Rome as they watched the dances and listened to the ancient hymns. Or perhaps the crowd chanted and stomped their feet along with the Salii, all of them honouring the god who had helped to make Rome the superpower it had become?

This dance they perform when they carry the sacred bucklers [the ancilia] through the streets of the city in the month of March, clad in purple tunics, girt with broad belts of bronze, wearing bronze helmets on their heads, and carrying small daggers with which they strike the shields. But the dance is chiefly a matter of step; for they move gracefully, and execute with vigour and agility certain shifting convolutions, in quick and oft-recurring rhythm. (Plutarch; Numa)

Artist impression of the Salii performing the ritual dance to honour Mars

I love learning about ancient religions not only for what they tell us about ancient cultures, but also for the uniqueness of the rites themselves, the origins and mythologies of the beliefs, and the glimpse they give us of what life was like in the ancient world.

Armed and dancing priests during the month of Mars? Who doesn’t like that?

Thank you for reading.

Ruins of the Temple of Mars Ultor (Mars the ‘Avenger’)