Greetings History-Lovers!

Welcome back to The World of The Blood Road, the blog series in which we’re looking at the research into the history, people, and places behind-the-scenes of the newest Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy novel.

If you missed the previous post on Roman Etruria, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part VII we’re going to be visiting one of the most sacred sanctuaries of the ancient world. We’re going to Delphi.

Are you ready to visit the oracle?

Let’s begin…

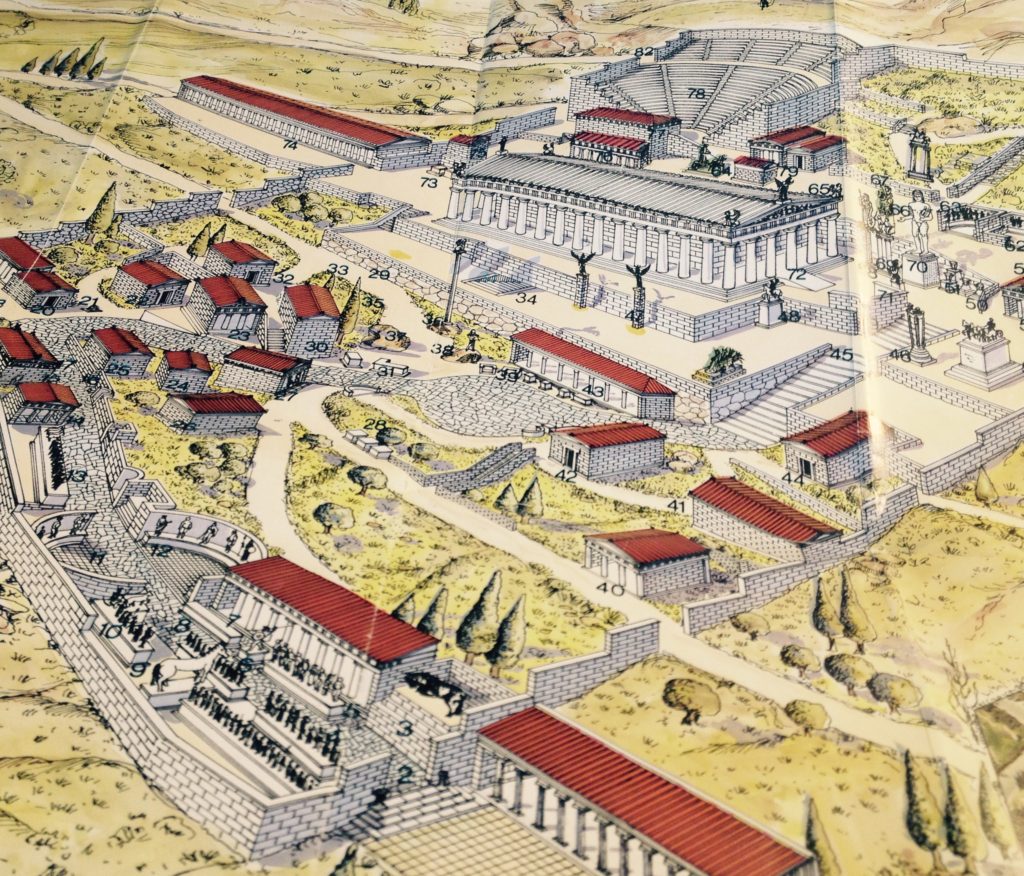

Speculative illustration of ancient Delphi by French architect Albert Tournaire.

Just as Delphi is perhaps one of the most well-known historical sites of Greece today, it was also one of the most famous and important places in the ancient world, sacred to both Greeks and Romans.

In this post, however, we’re not going to be discussing the history of Delphi. If you would like to read about that and my own experience walking through the sanctuary, you should definitely read this previous post by CLICKING HERE.

In this seventh part of The World of The Blood Road, we’re going to walk alongside ancient pilgrims, or theopropoi, on their way to consult the Pythia, the famous oracle of Apollo at Delphi.

…the high road to Delphi becomes both steeper and more difficult for the walker. Many and different are the stories told about Delphi, and even more so about the oracle of Apollo. For they say that in the earliest times the oracular seat belonged to Earth….

…I have heard too that shepherds feeding their flocks came upon the oracle, were inspired by the vapour, and prophesied as the mouthpiece of Apollo.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, 10.5.5)

The peaceful sanctuary of Athena Pronaia

People would come from all over the Greek and Roman world to consult the oracle at Delphi who spoke the words of Apollo himself, the god of art, music, healing and prophecy, common to both Greeks and Romans. More often than not, they would come from very far away to do this, but when they arrived at Delphi, they could not just step into line and wait to see the oracle in the temple. There was a process.

First of all, you had to get there, and whether you came over land from the direction of Thebes, or from the ancient port of Kirrha on the gulf of Corinth, you had to climb your way up to the god’s eyrie.

Timing was important, for the oracle was not there all day, everyday. The priests of the temple could give simple answers to simple questions by individuals regularly, but for cities seeking wisdom, or individuals with weighty questions, the Pythia herself would give her oracles once every month on the seventh day, except for the three months of winter when Apollo was said to be in the land of the Hyperboreans. During Winter, Dionysos was said to watch over Delphi.

Whenever you arrived in Delphi, you would probably have stopped at the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia to thank the gods for bringing you there safely.

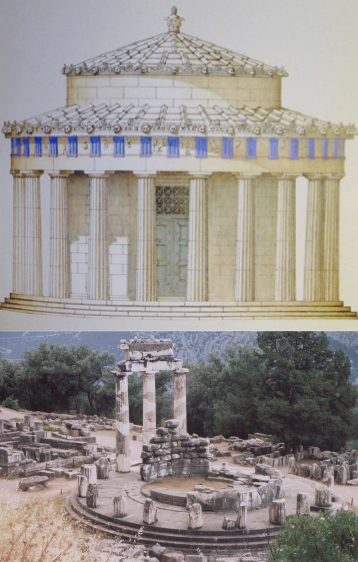

The Tholos in the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia (reconstruction by K. Iliakis)

This sanctuary was the sort of gateway or ‘entrance’ to the sanctuary of Apollo. It was located down the mountain from the main sanctuary, along the road from Thebes. Here, there were temples to Athena, Hygeia, Zeus and others. There were altars and a hero shrine too, all within the walled enclosure. If you were Roman, you might have recognized the statue of Hadrian looking over the sanctuary, for he loved Greece and visited Delphi twice during his reign.

This is a peaceful place, filled with whispering olive trees, birdsong, and light. In this sanctuary, the traveller could take a breath and prepare him or herself for the next stage.

Within the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia, there was the larger, ‘old’ temple of Athena (built c. 510 B.C.), and the smaller ‘new’ temple of Athena (built c. 380 B.C.) where pilgrims would have made their offerings.

Today, however, the main structure that draws the eye is the tholos, the round temple that stood between the two main temples of Athena. It is not known exactly what rituals took place inside this striking temple, one theory being that its shape echoed the round huts or structures of a more ancient time. The tiled roof was accented by lion heads about the perimeter an the metopes, some of which remain, depicted the Gigantomachy (battle of the Giants) and the Amazonomachy (battle of the Amazons).

Beside the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia, there also lay the long tiled roof of the Roman gymnasium, one of the more recent additions to Delphi, where Athletes participating in the Pythian Games, or travellers seeking to stay fit, might be training.

Most people, however, would have been eager to make their offerings to Apollo in the main sanctuary up the mountainside, and have their questions answered by the Pythia. However, it was not just a matter of walking in and doing so.

One had to be purified.

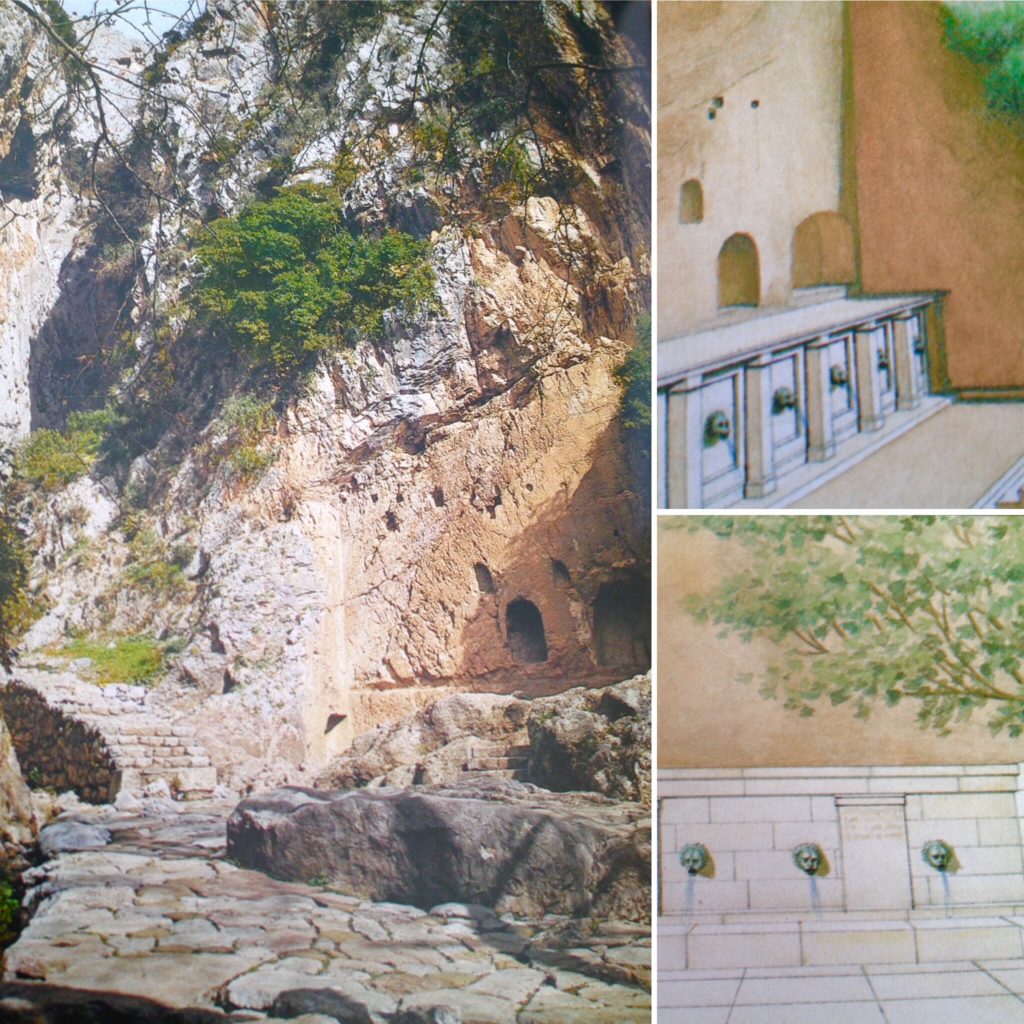

The Phaedriades, or ‘Shining Ones’ (Wikimedia Commons)

In the shadow of the twin peaks known as the Phaedriades, or the ’Shining Ones’, there lay the sacred spring of Castalia. The water that fed this spring came out from the Phaedriades and was used in the important purification rituals of Delphi. Even the Pythia purified herself with this water.

If one did not go through the purification, one could not enter the sanctuary which was about five hundred meters away. The line would have been long, especially if one arrived for the seventh day of the month.

Within a shaded court, there was a pool fed by lion-headed spouts. Stairs led down into the water where pilgrims washed their hands, face and hair with the sacred water. If one was guilty of homicide, however, the entire body needed to be washed in the Castilian spring.

The Castalian Fountain House where pilgrims purified themselves before entering the sanctuary. (Reconstruction by K. Iliakis)

Once a pilgrim had purified himself or herself, it was time to purchase offerings if you had not already brought some. Conveniently, there was an agora that the Romans had built, just before the entrance to the sanctuary of Apollo. Here there would have been small animals, votive sculptures, food and more available for purchase.

You might not have been able to see into the sanctuary yet, though you knew it was there, for as soon as one approached Delphi, there was a niggling feeling of awe and wonder that accompanied such proximity to this most holy place of Apollo’s, the place where he slew the great Python and where, ever since, heroes, kings and countries had come for his wisdom.

Once you stepped through the main gate into the sanctuary, the flow of people would have led you on.

Site map of Delphi showing the Sacred Way running up through the sanctuary of Apollo to the temple itself. Reconstruction by Dimitris Kyriakos and Dimitris Nassides based on research by the French Archaeological School)

As one walked along the Sacred Way of Delphi, one would have been struck by the amount of artworks, monuments and votive offerings along the way. It would have been like walking through a filled museum for the modern traveller, which is fitting as Apollo was the leader of the Muses.

The first thing one would have seen are various statues groups that included the Bronze Bull of the Corkyrans, thirty-seven statues of the Spartan admirals, and votive statues of the Arcadians. These lined the road on both sides, and were followed by statues created by the famed sculptor, Phidias, to commemorate the Athenian victory over the Persians at Marathon.

One could have taken shelter in the shade next at the small stoa that was there alongside the votive statues of the Argive kings which were across from the wooden horse of Troy, and the statue group of the famous Seven against Thebes.

Perhaps some travellers would have stopped to look at all of the works of art, to feel the connection to an ancient past. If one was Roman, perhaps one might have felt a bit more out of place, like an intruder, or invader, there to seek the wisdom of the god you shared with the Greeks walking beside you?

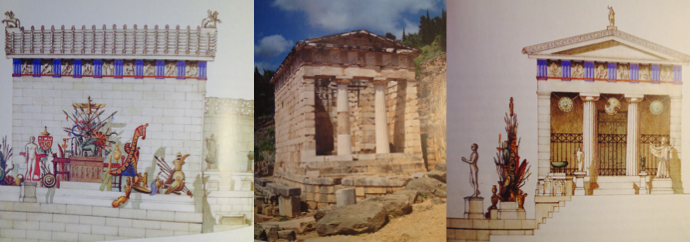

The Athenian Treasury along the Sacred Way. (Reconstructions by K. Iliakis)

The road then widened, and perhaps the crowd walking up the mountain to the main temple spread out. Next, where the road began to switch back on its way up, one came to the various treasuries where cities from across the Greek world kept riches, offerings and trophies. The treasuries of the Thebans, Beotians and Poteideans were there, squat stone structures with tiled rooftops, their doors either open to their respective citizens, or barred to outsiders.

Between the latter two treasuries was a reminder of where one was in that moment, for there was the enormous, carved omphalos stone, the ‘navel’ that told one Delphi was the centre of the world.

Then came the grand treasury of Athens with its beautiful facade and metopes depicting the deeds of Theseus and Herakles. There were banners, enemy armour and more adorning the outer steps, and riches filling the interior, there since it was dedicated to the victory at Marathon. Perhaps some were weather-worn, or perhaps Rome had already taken some, but it was nonetheless impressive, right down to the text inscribed upon the outer walls.

Continuing along the Sacred Way, one passed the bouleuterion, the Delphic council house, and the treasuries of the Syracusans and Megarians as well as other monuments and altars.

The Sybil’s Rock

If one was nervous about approaching the god with one’s question, one might have had to pause at what was seen next. In the shadow of the long temple of Apollo, which now stood above you on the next terrace, one now stood before two rocks: the rock of Leto, where Apollo slew the great Python, and the rock of the Sibyl, where the first oracle spoke Apollo’s words to the world.

What must it have been like for an ancient pilgrim to stand there, further unnerved by the gaze of the Naxian Sphinx on its ten meter column, looking down on you! Did the sound of the crowds fall away as you contemplated your purpose in being there? Could you hear the roar of the Python as Apollo loosed his arrows?

The experience was, no doubt, different for everyone.

The Naxian Sphinx in the museum at Delphi.

Past the treasury of the Corinthians and the Delphic prytaneion, the magistrates’ hall, one then mounted the Tarentine stairs beneath the great golden tripod with its thick serpent columns, a battle-offering for the Greek victory over the Persians at Plataea. To your right you would have seen another area with various large columns and votive statues of the kings Attalos and Eumenes, the stoa of Attalos which had two levels, and where people gathered to rest or talk in the shade.

This area was also dominated by the golden chariot of Helios, offered to Apollo by the Rhodians.

But your eyes would now have been drawn inexorably to your left where the colossal statue of Apollo with his lyre, and of the goddess Athena atop a soaring bronze palm stood before the temple of Apollo itself.

If it was the seventh day of the month, then perhaps it was difficult to move in the crowd of pilgrims awaiting their turn make their offerings upon the great altar of the Chians which faced the temple entrance.

The Altar of the Chians before the Temple of Apollo (Wikimedia Commons)

Would you have been frustrated to see those with promanteia – the right to see the oracle first – skip the line? These included the Delphians themselves, as well as people from Chios and some other places. If you were there, in Delphi, no doubt your questions were pressing, but there was plenty to see and do while you waited for your turn.

Looking out over the mountainside, down toward the South, the sun would have warmed your face as you gazed down on the valley of sacred, silver-leafed olive groves to the sea beyond. The sound of cicadas and birdsong might have been matched only by the hum of the gathered pilgrims.

If you still had to wait your turn to enter the temple, you could have walked up to the next terrace, above the temple, passed various columns and monuments, including the shrine to Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles. Then, to more shrines and monuments until you paused before the great bronze charioteer, and the bronze statue group of the lion hunt of Alexander the Great, dedicated by his general Crateros.

The Charioteer of Delphi

Up the hill there was another enclosure that included the rock of Kronos and the meeting hall of the Cnidians, but you had no need to go there, for you were drawn by the sound of music coming from the great theatre of Delphi which rose up the mountainside to your right. Perhaps musicians were practicing for the coming Pythian Games, or perhaps a lone poet was practising his recitation before an empty theatre, a solo offering to the ears of Apollo himself?

The Stadium farther up the mountain from the sanctuary was the site of the Pythian Games and seated up to 7000 spectators

Along the path from the top of the theatre, on into the pine-scented air of Parnassus, the stadium stretches away. Athletes are training there, running, throwing the discuss, testing their strength and skill against each other. Or perhaps they are sitting in the sun gazing up at the trees and rocky slopes above?

You think about going to watch, but then your name is called. It is your turn to see the oracle.

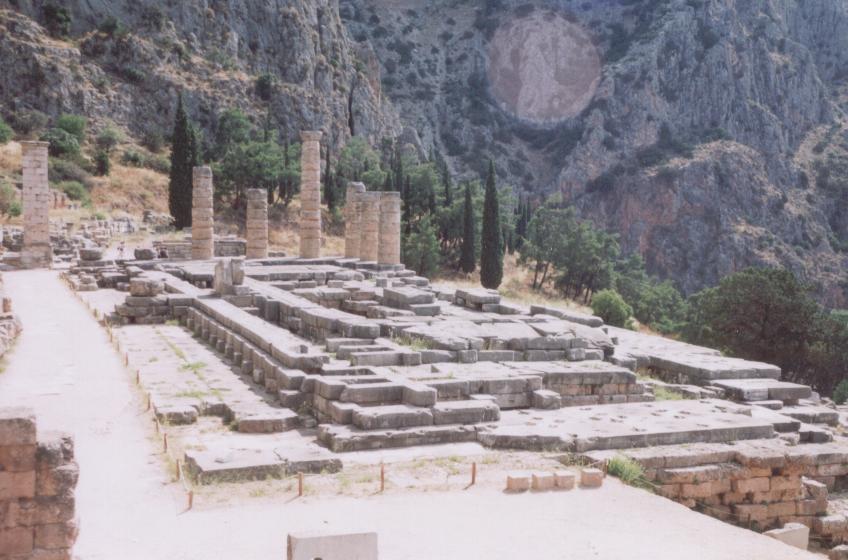

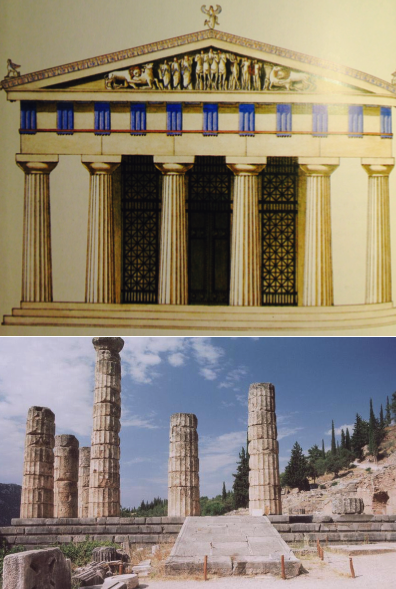

The Temple of Apollo

The temple of Apollo is the focus of the entire sanctuary. It is the home of the god. As one approaches it, perhaps one feels nervous anticipation? You are, after all, going to step into the presence of Apollo. You don’t want to get things wrong either, for then your journey might be wasted.

After you have cleansed yourself with Castalian water, you might walk up to the altar before the temple to make your offering of pelanon, the honeyed bread that all pilgrims give. You would give money too, the amount dependent upon your financial state. And then, you would offer a goat, the preferred blood offering. This act would have awoken a sense of morality in you, and you pray that when the cold water is poured over the animal, it shivers a suitable amount, for if it does not, then there will be no prophecy for you.

The Temple of Apollo at Delphi (reconstruction by K. Iliakis)

Once your offering have been made and accepted, you are told by the priests that you may make your way into the temple.

The time has come.

First you pass through a small forest of columns and the pronaos of the temple where the words of Delphi’s famous maxims arrest you.

‘Know thyself’

‘Nothing in excess’

‘Surety brings ruin’

Do you doubt yourself as you step into the temple? Are you guilty of the hubris the Gods so despise in mortals?

How many people turned away at this point, unable to step further?

You can read all about the Delphic Maxims by CLICKING HERE.

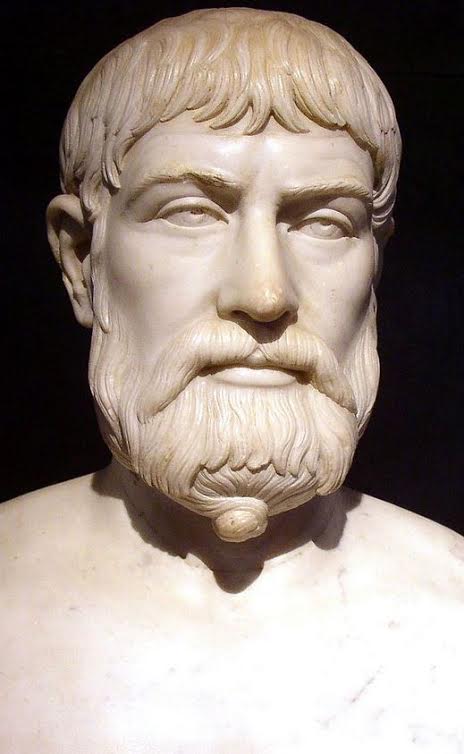

But you step into the temple, as sure of yourself as you can be, and your eyes are treated to some of the most beautiful works of art you have seen, frescoes, votive objects such as musical instruments, kraters, gilded tables, chariots, weapons, crowns and more, all offered to Apollo. There is even the iron throne that was where the great epinikion poet, Pindar, sat when he recited his words to Apollo at Delphi.

And that saying, in these fortunate circumstances, brings the belief that from now on this city will be renowned for garlands and horses, and its name will be spoken amid harmonious festivities. Phoebus, lord of Lycia and Delos, you who love the Castalian spring of Parnassus, may you willingly put these wishes in your thoughts, and make this a land of fine men. All the resources for the achievements of mortal excellence come from the gods; for being skillful, or having powerful arms, or an eloquent tongue. As for me, in my eagerness to praise that man, I hope that I may not be like one who hurls the bronze-cheeked javelin, which I brandish in my hand, outside the course, but that I may make a long cast, and surpass my rivals. Would that all of time may, in this way, keep his prosperity and the gift of wealth on a straight course, and bring forgetfulness of troubles. Indeed he might remember in what kind of battles of war he stood his ground with an enduring soul, when, by the gods’ devising, they found honour such as no other Greek can pluck, a proud garland of wealth.

(Pindar, Pythian 1, For Hieron of Aetna)

Pindar

Beyond the piles of offerings about you, and the other maxims inscribed upon walls and plaques, there is a wood and ivory screen that separates the first room of the temple from the cella.

One of the priests ushers you through the screen, and on the other side you see the main altar where Apollo looks down upon you. At the god’s feet is the pythomantis, the eternal flame that is always tended by the Pythia and the Hestiades, the five chosen Delphic maids who continually feed the flames with fir wood from the mountainside.

The temple smells strongly of smoke, of oil and burning wood, but there is another smell you cannot discern, something slightly foul coming from a chamber beneath the cella.

Besides the Delphic maids, there are three priests of the oracle, and the five holy men descended from Deucalion, whose ark landed on Parnassus during the Great Flood.

One of the priests steps forward to ask what question you would pose to Apollo, and then he leads you, under the watchful gaze of the others, down the steps to the oracular adyton below the cella.

It is dark, lit only by the slightest of fires as you descend into the earth, a faint scent of sulphur stinging your nose. When you reach the adyton, you see the great omphalos stone, covered by the agrenon, the wool net with golden eagles upon it. There are also ancient statues of Apollo himself in wood and gold. You would observe them more closely, but then your heart is pounding and you sweat, and then you see her: the Pythia.

Apollo and the Pythia who uttered his prophecies to mortals

She sits upon a bronze tripod, above a crack in the earth, a branch of laurel in her hand, her eyes shaded by the cowl of her cloak. Upon the floor is a cistern with water from the spring of Cassiotis.

The priest speaks your question to the Pythia, there is a pause, and then she utters the words of Apollo…

…the untrod Parnassian cliffs, shining, receive the wheel of day for mortals. The smoke of dry myrtle flies to Phoebus’ roof. The woman of Delphi sits on the sacred tripod, and sings out to the Hellenes whatever Apollo cries to her. But you Delphian servants of Phoebus, go to the silver whirlpools of Castalia; come to the temple when you have bathed in its pure waters; it is good to keep your mouth holy in speech and give good words from your lips to those who wish to consult the oracle. But I will labor at the task that has been mine from childhood, with laurel boughs and sacred wreaths making pure the entrance to Phoebus’ temple, and the ground moist with drops of water; and with my bow I will chase the crowds of birds that harm the holy offerings. For as I was born without a mother and a father, I serve the temple of Phoebus…

(Euripides, Ion, Line 82)

Today, we know very little of the divination process at Delphi. Scholars continue to try and piece together a picture of the process of what happened and what was involved from a few mentions in ancient sources.

Often, answers were given in riddles, if they were not ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers. Sometimes, the oracle would give a punishment or penance such as that given to Herakles after the murder of his family.

The archaeological site of Delphi as seen from above the theatre, with the temple of Apollo below.

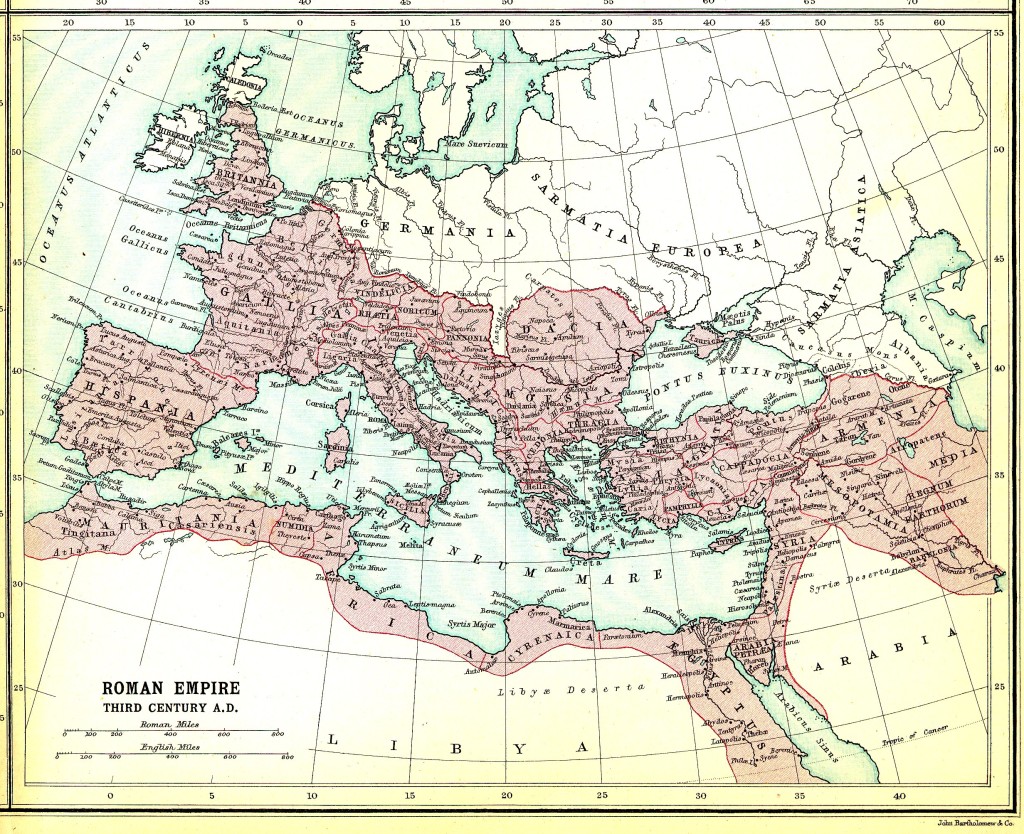

Despite Delphi’s sacred role in the ancient world, including to the Romans, not all men of the Tiber were kind to the sanctuary of Apollo.

Sulla and Nero both stripped the sanctuary of bronze and marble statuary. However, Domitian repaired the temple of Apollo in A.D. 84, and Hadrian, a great Hellenophile, lavished gifts upon the sanctuary when he visited in A.D. 126 and 129.

Even Caracalla, who is emperor in The Blood Road, ordered the restoration of parts of the sanctuary, perhaps as atonement for the murder of his brother, Geta.

The sights described above on our virtual pilgrimage through the sanctuary are pieced together with information from the archaeological record and ancient sources such as Pausanias, Euripides and others. There are many gaps in our knowledge, especially around the actual rituals of divination.

One thing is certain, however, and that is the awe that both ancient and modern visitors to Delphi experience. Whether the sanctuary was at its peak during the Golden Age of the Classical period, or whether it lay in romantic ruin as it does today, one cannot help but feel overwhelmed by Delphi as one walks in the footsteps of millions who sought the wisdom of Apollo.

I’ve been to Delphi several times, and each time feels like the first. And after I’ve walked the sacred way, past the treasuries and empty spaces once filled by incredible works of art, I like to sit at the top of the theatre and look down over the sanctuary to the temple of Apollo and the valley of sacred olive trees far below, leading to the sea. The crowds about me disappear and all I can hear are birds, cicadas and the wind. I feel peace like nowhere else, and in that peace, if you listen closely enough, you might just hear music washing down that mountainside where Apollo made his mark on the world.

Stay tuned for Part VIII in The World of The Blood Road when we’ll be visiting Antioch, the ‘Rome of the East’.

Thank your for reading.

The Blood Road is available on-line now in e-book and paperback at major retailers. CLICK HERE to get your copy. You can also purchase directly from Eagles and Dragons Publishing HERE.

If you are new to the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series, you can check out the #1 best selling prequel, A Dragon among the Eagles for just 1.99 HERE.