Salvete Romanophiles!

We have a special guest post on Writing the Past this week!

Author, A David Singh is here to talk to us about the idea of ambition in Roman society. We may not be surprised by the fact that Romans were ambitious – one doesn’t build an empire without ambition – but ambition took different forms for people at all levels of Roman society. David has done an excellent job of outlining this, so be sure to keep reading!

If you haven’t read David’s previous guest post about slavery in ancient Rome, then you should also read that by clicking HERE.

For now, it’s time to learn all about Roman ambition!

Ambition in the Roman Republic

By A. David Singh

As some of history’s pre-eminent over-achievers, ancient Romans championed a quality that transformed their city-state to the foremost civilization of antiquity: ambition!

At its core lay the desire for wealth, power, and prestige. In that respect it was no different from ambition as seen in today’s world.

Let’s start by looking at this need to create a better life among those at the lowest rung of the Roman strata.

Slaves

Slaves were not citizens of Rome. Not only were they denied statehood, they were also stripped of personhood. Roman society considered them as mere objects or possessions—with no more agency than a piece of furniture or cattle.

Given these circumstances, one might be tempted to imagine slaves as men and women devoid of ambition, with no hope for rising above their lot in life. But that was hardly the case.

Most slaves harboured one viable ambition—to break free from the shackles of slavery and become Roman citizens.

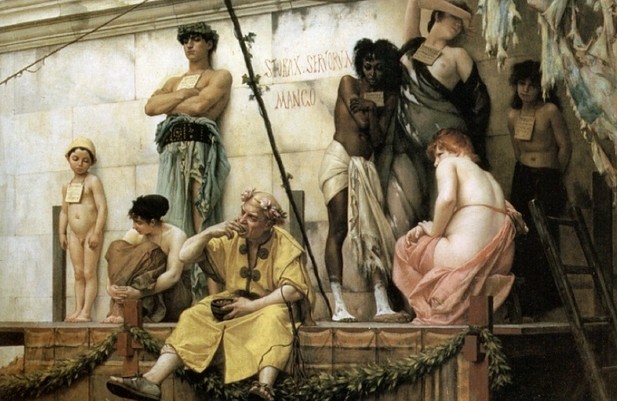

The Slave Market – oil painting by Gustave Boulanger, 1886 (Wikimedia Commons)

If a slave showed the “right” attitude toward his servitude and discharged his duties satisfactorily—these attributes being open to interpretation by the masters—the slave could be set free by appearing before a magistrate. Once the magistrate had confirmed that the slave was a freedman, the master would slap the slave as a final insult before he started his new life.

Quite often, masters bequeathed freedom to their slaves in their wills. Rarely, slaves could earn their own freedom if they were able to raise enough coin to buy themselves out of slavery.

The process of becoming freedmen and freedwomen was called manumission.

Because house slaves worked in direct contact with their masters, they could endear themselves to those who held power over them. As a result, house slaves had a better chance of getting manumitted compared to those working on country estates and in mines.

Once manumitted, the slaves transitioned into freedmen/freedwomen, and became citizens of the great city of Rome. Now they were deemed human, and not objects anymore—a significant upgrade in their station.

Freedmen and freedwomen

As citizens, freedmen and freedwomen were entitled to all the civil rights in Rome. However, they were not entirely free of their former masters. Those masters exercised some degree of hold over them by becoming their patrons.

As patrons, the former masters helped them make strides within the Roman society—by opening doors and helping them both financially and professionally. In return, the clients (freedmen and freedwomen) had to provide services to their patrons, most of which involved either making the patrons wealthier, or by extending their patrons’ prestige further into Roman society.

Freedmen could not hold political office. So they endeavoured to make a better life for themselves through other means. The easiest avenue was to acquire wealth from business ventures.

Rome was filled with waves of such newly manumitted freedmen eager to make their mark. Blacksmiths, butchers, barbers, cloth-merchants, and tradesmen dotted the over-populated city, with a singular goal in their minds: make more coin!

Some even amassed their own slaves—the more slaves a man had, the more prestigious he was considered. This was their way to prove their “equality” to the society that had once enslaved them.

Over time, rich freedmen started marrying into traditional but impoverished Roman families. This became a cultural norm, as it proved to be of mutual benefit—the old Roman families became richer, thanks to the nouveau riche, while the freedmen elevated their prestige and circle of influence.

Even though the freedmen and freedwomen (or children born to them before manumission) could not hold political office, that was not the case for children born to them after they’d gained freedom. Many freedmen and freedwomen encouraged these children to hold political office, thereby vicariously fulfilling their own ambition through their children.

Lastly, the option to join the Roman legions was readily available. Rome was an ever-expanding war machine, eager to recruit men younger than forty-five years. As a legionary, a young freedman could travel the Roman world, earn coin, and even rise to become a centurion. All in all, that was a good plan, unless one was unlucky enough to feel the pointy end of a barbarian’s sword.

The Roman legions

Legionaries—or the foot-soldiers—were the lowest rank in the Roman legion. They fell into several categories, although these categories did not have official standing.

If a legionary held a modicum of ambition, he’d aspire to become an immunis—or a legionary with special skills, like carpentry or weapon-making. It was even better if he could read and write. He could then become a clerk and be responsible for communications and record-keeping.

Becoming an immunis allowed one to leave the common herd behind, along with all the menial tasks like latrine duty and heavy-lifting. Though this was only a minor step-up in prestige, it was not an unattractive one by any standard.

A legionary with no aptitude for special skills aspired to become a principalis. Examples include a tesserarius, who was responsible for sentry duty, and an optio—who was the second-in-command of a century.

Though the salary of a legionary did not increase with these step-ups, any legionary mindful of his dignity and prestige aimed to climb this unofficial hierarchy. His reputation and influence within the legion played a critical role in his ascent.

Roman legionaries marching in uniform, re-enactment (courtesy Pixabay)

The first official non-legionary rank was a centurion. Principales stood the best chance of becoming centurions.

Centurions were the backbone of the legion. They were responsible for the day-to-day activities of their legionaries, escorting prisoners, and conducting diplomatic missions. During battle, centurions led the charge alongside their men.

Interestingly enough, not all centurions in a legion were equal (or, to borrow from Animal Farm, some were more equal than others). The centurion of the 1st century, 1st cohort (Primus Pilus) was the senior-most, while the centurion of the 6th century, 10th cohort ranked the lowest. Among other privileges, this gradation determined who got the best seat in a tavern, and who was the last to conduct a fatigue party in the rain.

That’s prestige on raw display, isn’t it?

The annual salary of a legionary was 1,200 sesterces, and a centurion’s was 20,000 sesterces. The Primus Pilus commanded a whopping 100,000 sesterces (during the 1st & 2nd centuries CE).

While a legionary—upon becoming a centurion—might feel satisfied with his progress up the ladder, that was likely to be the last stop in his career. The ranks above a centurion were populated by men of senatorial classes.

The only exception was the Camp Prefect, or Praefectus castrorum, who outranked the military tribunes (we’ll meet them shortly). The camp prefect was chosen from long-standing centurions of a legion, and would have likely been a Primus Pilus in the past. As the third senior-most officer in a legion—outranked only by the Legatus and Tribunus laticlavius—he was responsible for training and equipment, and held the command of his legion in his superiors’ absence.

And that brings us to the senatorial classes.

Senators and the Path of Honours

During the early republican period, senators were a group of unelected men who advised the magistrates. From the 3rd century BCE onwards, the senate increased its power, and virtually functioned as the government of Rome by exercising control over the assemblies and the magistrates.

Education in rhetoric and experience in law were considered essential preparations for political life. And boys from prominent families were groomed from an early age in these disciplines.

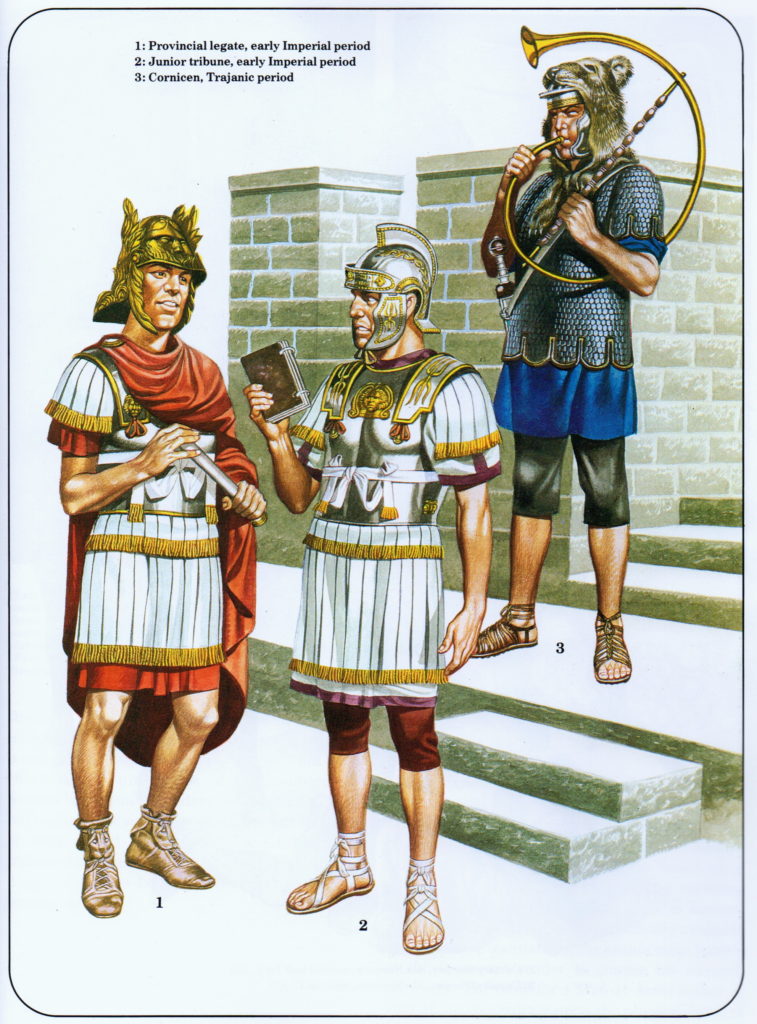

Young men harbouring senatorial aspirations might even join the legions as military tribunes. They were responsible for the administrative duties of their legions. Military tribunes outranked the centurions, but were below the camp prefect.

Their military competence varied (some may have had prior experience in auxiliary units), but what remained constant was their shark-like determination to ascend the Path of Honours.

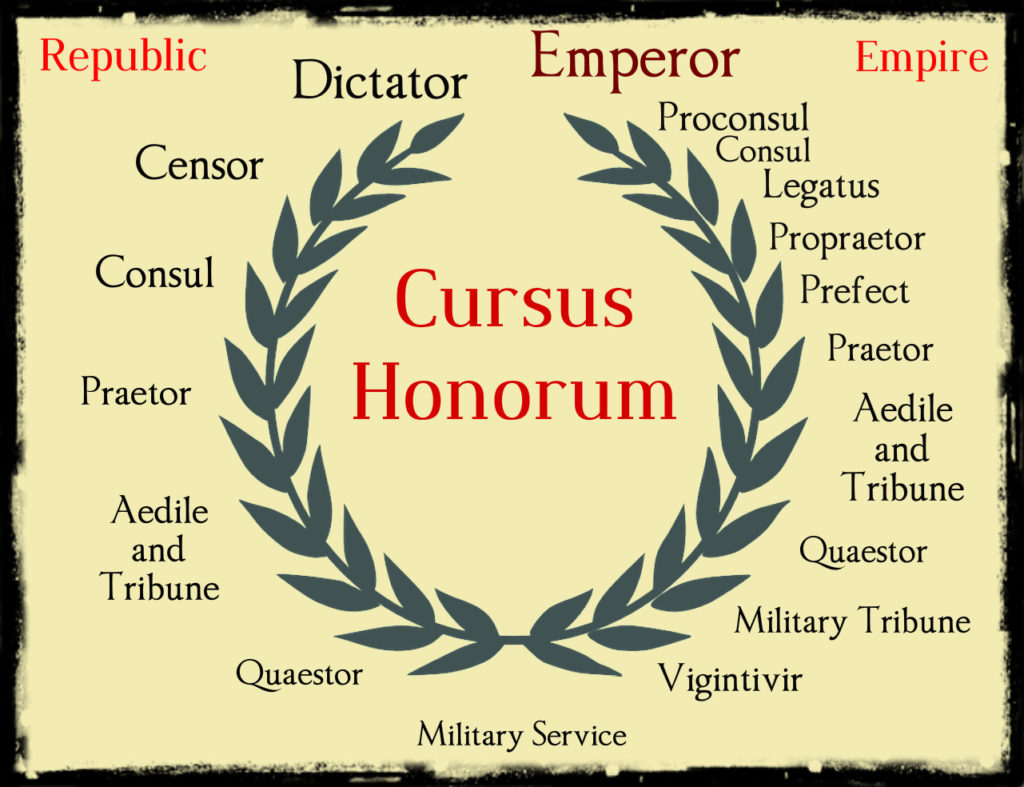

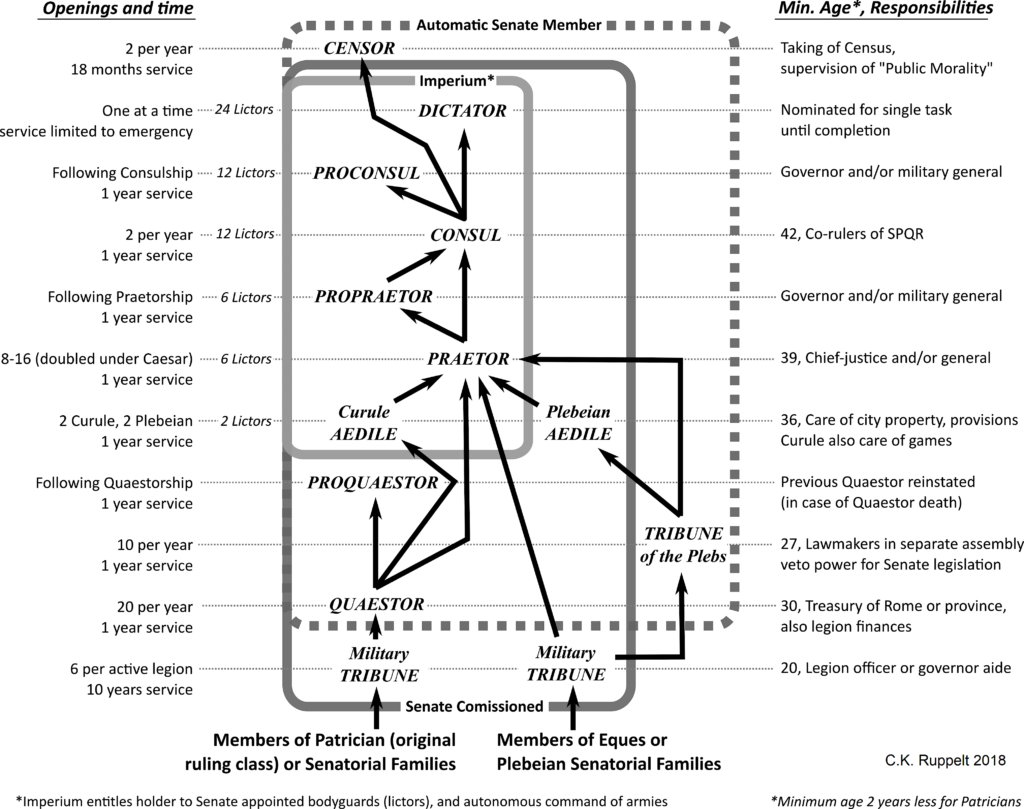

The Path of Honours (Cursus Honorum) as in the time of Julius Caesar – 1st century BCE (courtesy C. K. Ruppelt – Wikimedia Commons)

Elected officials in the republic were called magistrates. Once a man was elected to his first magistracy, he was automatically admitted to the Senate.

Quaestores were the lowest magistrates, responsible for the state and military treasuries. They were stationed in Rome and its provinces, and were also embedded in the legions.

On the next rung were aediles, who supervised public works—repair of temples, streets, sewers, public buildings, and aqueducts. They were in charge of markets (weights and measures, and distribution of grain). Lastly, the aediles organized festivals and public games. Ambitious aediles spent prodigious amounts of coin to attract publicity and vote-catching, to advance their political careers even further.

Tribune of the Plebs: This office was formed in the early republican days to protect plebeians from patricians, when patricians held all public offices. As the title suggests, only plebeians could hold this office. Though technically not magistrates, they functioned very much like the magistrates of the Roman state; they could propose legislation and summon the senate. An important function of the plebeian tribunes was to veto decisions by the consuls and other magistrates, thus protecting the interests of the plebeians.

Praetors were magistrates responsible for the Roman judiciary. They acted as chief judges and at times as deputies to the Consuls. By 80 BCE, Sulla increased the number of Praetors to eight: two were responsible for civil matters, and six for criminal.

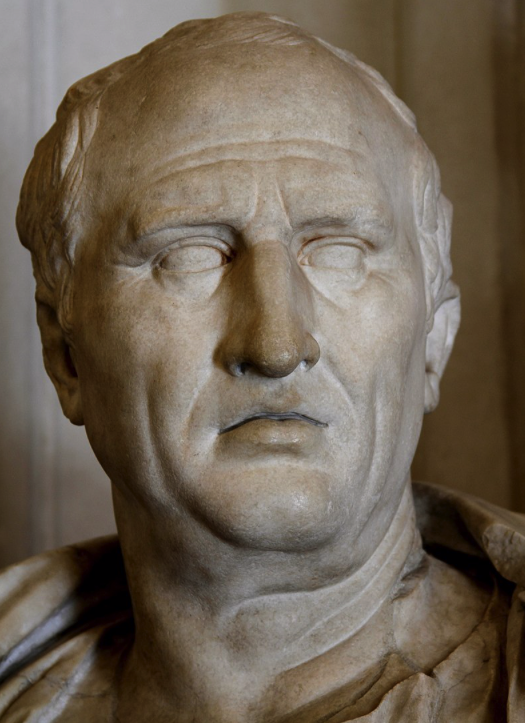

Two consuls were elected each year. They were the joint heads of the Roman state and commanders-in-chief of the legions. Consuls presided over Senate meetings and implemented its decisions. Both plebeians (from 367 BCE onwards) and patricians could become consuls. Interestingly, years were named after the Consuls, e.g. what we call 63 BCE was known as the “Year of the Consulship of Cicero and Hybrida”.

In times of crisis, a Dictator could be appointed. His term could be no longer than six months. But during his time in office, he possessed supreme military and judicial authority. An exception was Julius Caesar, who was proclaimed Dictator for life.

Partial view of the Roman Forum. The Curia Julia (or Senate House) is seen in the centre (courtesy Pixabay).

Governors of the Roman Provinces were selected from former praetors and consuls. Accordingly, they were named pro-praetors, or pro-consuls. They also held military command when directed by the Senate.

Governorship of the provinces gave these men free rein over the provinces, and this position was vastly abused to accumulate enormous amounts of wealth. However, most governors considered this their right, since they were not paid a salary during their decades as senators.

The ascent from military tribune to consul (and beyond) brought incremental prestige and influence to the men. No wonder, the senatorial classes aggressively engaged in the pursuit of political power for themselves, and for their family and friends.

Volatile alliances, political factions, bribery, corruption, one-upmanship, and even marriages and divorces formed the backdrop against which the lives of senators unfolded.

In the Roman republic, senatorship and the Path of Honours remained the sole domain of men. Women could not vote, become senators, or hold any political office.

So, what did women do to quench their ambition in a male-dominated Rome?

Women and ambition

Roman women lived under the guardianship of the primary male member of their family—the paterfamilias. Fathers played this role during their childhood, and the responsibility was handed over to husbands at marriage. Thus, the social identity of women was defined by being someone’s daughter, and later, by being someone’s wife.

Although there was no shortage of loving marriages in Rome, by today’s standards those women lived in relative submission and obscurity. Therefore, their avenues of ambition have to be understood within the context of their societal limitations.

Trades were open to free born women and freedwomen—both married and unmarried. Plebeians took on vocations like midwifery, hair-dressing, basket-weaving, and cooking, among others. Even patrician women were expected to sew and weave.

On the home front, wives of prominent families would co-host banquets with their husbands and preside over religious activities of the household. Many were well read in Greek and Latin literature.

The last decades of the republic saw the emergence of independent women—especially among the patrician families—who were unwilling to live within the sphere of traditional female virtues like modesty, devotion, and frugality.

Although women could not vote in elections or hold office, the political milieu of the 1st century BCE was not impervious to women’s influence.

Graffiti found on the walls in Pompeii indicate that women frequently endorsed candidates for political office. It is quite likely that women attended rallies and canvassed for their candidates.

Some even played a robust role in Roman politics, e.g. Servilia, who—because of her proximity to Julius Caesar—was a figure to reckon with.

Rome was steeped in religion. Priesthood conferred prestige and special privileges upon women, that others did not enjoy.

Vestal priestesses belonging to the cult of goddess Vesta were considered fundamental to the continuance and security of Rome.

They could free slaves and criminals by touching them; they had a reserved place of honour to watch games and spectacles; they could own property, and give evidence without anyone doubting their word, and were even entrusted with the safe-keeping of important wills and state documents.

Vestal priestesses fulfilled their duties for a period of thirty years, after which they would command marital alliances in prestigious Roman families.

Although Roman ambition came in many flavours, the core drive was to excel and elevate as a collective whole. That ancient model still shines a light for today’s world, nudging us to strive for a better tomorrow. Thank you for your kind attention.

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE) – Roman senator, lawyer, scholar, and consul (63 BCE) (courtesy Pixabay).

Author Bio

A neurosurgeon by profession, A. David Singh operated on brains invaded by tumors, aneurysms, and other vile maladies. Funnily, after turning a couple (or more) gray hairs, a rather strange affliction invaded his own brain. Characters from a parallel universe besieged his brain cells and refused to leave, unless David transcribed their lives onto paper. At first, he resisted the assault on his cerebral faculties, but these denizens of the Magical Rome Universe kept prodding his gray cells with their antics, forcing him to write their story.

You can enter the Magical Rome Universe through the novel Dead Boy’s Game and the Broken Vow.

In Magical Rome, three Romans strive to become senators—each to satisfy their unique and diverse ambitions. Villius is a senator’s apprentice, Julius is a victorious centurion, and Calpurnia…well, Calpurnia is a woman living in a man’s world.

To read this story, please visit https://MagicalRome.com

I’d like to thank David for writing such an interesting post about ambition. It’s fascinating how ambition plays a part at every level of society.

Be sure to check out David’s website and his new book in the Magical Rome Universe.

And if you have any questions about ambition in Roman society, be sure to ask your questions in the comments below so that David can answer them.

Thank you again to A. David Singh, and thank you to all of you for reading!