The World of Warriors of Epona – Part I – Epona: Goddess of Horses

The Eagles and Dragons saga is marching on, and so I’m very excited to begin a new series of blogs posts based on the newest release, Warriors of Epona.

Writing the Eagles and Dragons series has been a fantastic and exciting adventure thus far, for me and for the characters inhabiting this world. And with each new book, I’ve tried to explore new realms, new areas of thought and belief, and to plumb new depths of the human experience.

In Warriors of Epona Lucius Metellus Anguis’ journey leads him down a very different path to a place that is both beautiful and terrifying.

I do hope that you enjoy the next phase in this adventure.

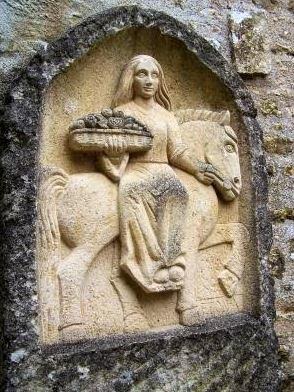

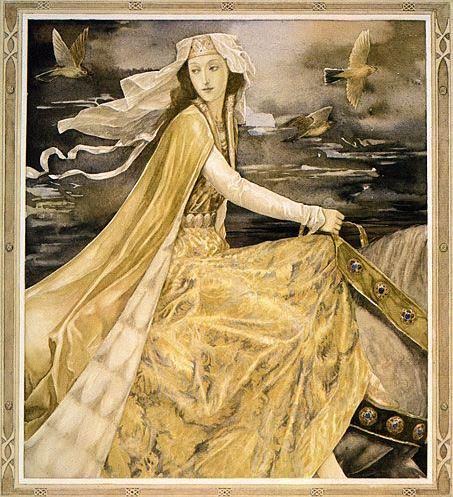

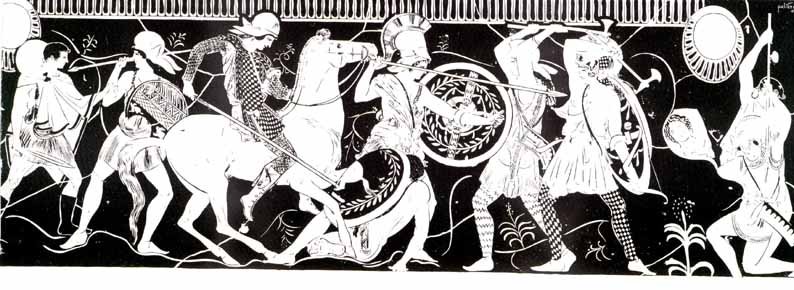

Epona and horses (Wikimedia Commons)

In Part I of The World of Warriors of Epona, I want to introduce you to a new character in the series, a goddess.

In Warriors of Epona Lucius has started the next phase of his military career as the praefectus of a Sarmatian cavalry ala. To read more about the Sarmatians, CLICK HERE.

Originally, Epona was a Celtic horse goddess, and some believe that her worship spread out from Alesia, in Gaul, at the time of Caesar’s conflict there with the Celtic war leader, Vercingetorix.

The interesting thing about Epona is that she came to be widely worshiped by Romans as well. This was a truly unique circumstance for a Celtic goddess, for worship of such deities was usually local in nature, and then they were often combined with a Roman god (for example the worship of Sulis Minerva at Bath).

Epona riding side saddle

However, the worship of Epona spread across the Roman Empire, especially among cavalrymen, and dedicatory inscriptions and altars to her have been found largely along the Rhine and Danube frontiers, but also in Gaul and Britannia.

She was also associated with plenty, and some of the few representations that survive show her holding sheaves of wheat. She was also associated with apples.

The Roman festival of Epona was celebrated on December 18th.

I have always been drawn to Epona since I read the Mabinogion, the compilation of early Welsh tales, or ‘Triads’. In the tale Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed, the otherworldly woman, Rhiannon, is a reflection of the Goddess Epona, riding a brilliant white horse, followed by three white, red-eared hounds, and of course the birds of Rhiannon.

In Warriors of Epona, I chose to portray the goddess, who is Lucius’ new protector, as Rhiannon is portrayed in the Welsh Triads. If you have never read Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed, I highly recommend it as it beautifully portrays some of the strongest archetypes of ancient Celtic myth.

Here is an excerpt from Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed:

Once upon a time he [i.e. Pwyll] was in Arbeth, a chief court of his, with a feast laid out and great hosts of men all around him. After the first course, Pwyll got up to go for a walk and made for the top of a mound which was above the court and was called Gorsedd Arbeth.

‘Lord’, said one of the court ‘it is a peculiarity of the mound that whatever high-born man might sit upon it, he will not go away without one of two things: either wounds or blows, or his witnessing a marvel.’

‘I have no fear of wounds or blows in the midst of this host. A marvel, however, I would be glad to see. I will go,’ he continued ‘ and sit on this mound’. And he went to sit on the mound.

As they were seated, they could see a woman on a large stately pale-white horse, a garment of shining gold brocaded silk about her, making her way along the track which went past the mound. The horse had an even, leisurely pace; and she was drawing level with the mound it seemed to all those who were watching her.

‘Men’ said Pwyll ‘ is there any of you who recognizes that lady on horseback over there?’

‘There is not, my Lord,’ they replied.

‘One [of you] go up to her to find out who she is’ he said.

One [man] got up, but when he came onto the road to meet her, she had [already] gone past. He went after her as fast as he was able to on foot, but the greater was his speed, the further away from him she became. When he could see that following her was to no avail, he returned to Pwyll and said to him:

‘Lord, it is no use anyone in the world [trying] to follow her on foot.’

‘Aye,’ said Pwyll ‘go back to the court, and take the fastest horse that you know, and go after her.’

He took the horse and off he went. He got to smooth open country, and he began to set his spurs to the horse; but the more he struck the horse, the further away she became. Yet she still had the same pace with which she had begun. His horse flagged, and when he noticed his horse’s slackening pace, he returned to Pwyll.

‘Lord,’ said he ‘it is no use following that Lady over there. I haven’t known any horse in the land faster than this one, but [even on this] following her was to no avail.’

‘Aye’ said Pwyll ‘there is some kind of a magical meaning to this. Let us go [back] to the court.’

[So] they went [back] to the court, and passed the rest of that day. The next day they arose and that [too] passed until it was the hour to eat. After the first meal [Pwyll spoke thus]:

‘We will go – the company that we were yesterday – to the top of the mound. And you,’ he said to one his retainers ‘take with you the fastest horse you know in the field.’ And that the retainer did. They [then] made for the mound with the horse.

And, as they were sitting, they could see the woman on the same horse, with the same apparel about her, coming up the same road.

‘Look!’ said Pwyll ‘here comes the lady on horseback. Be ready, boy, to find out who she is.’

‘Lord, that I’ll do gladly.’

Thereupon, the lady on horseback drew level. The boy then mounted his horse, but before he had [even] settled in the saddle, she had already gone past, and there was a distance between them. Her pace was no different from the day before. He [too] put his pace at an amble, supposing as he did that however slowly his horse went, he might be able to overtake her. But it was no use. He loosed his at the reins, but got no nearer than if he had been on foot; and the more he beat his horse, the further away she became. [Yet] her pace was no greater than before. Since he saw it was useless [trying] to follow her, he returned, coming back to Pwyll.

‘Lord,’ said he ‘there is no more this horse can do than what you have seen.’

‘[So] I saw’ replied [Pwyll] ‘ its pointless anyone pursuing her. But between me and God,’ he continued ‘she has a message for someone on this plain, if obstinacy would [only] allow her to say it. Let us go back to the court.’

They came [back] to the court and spent the evening in song and carousel as they pleased.

The next morning, they passed the day until it was the hour to eat. When they had finished the meal Pwyll announced ‘Where is that group of us that went up on the mound yesterday and the day before?’

‘Here [we are], my Lord’ said they.

‘Let us go [then],’ said he ‘to sit upon the mound. And you’ he said to his stable-boy ‘saddle my horse well and bring him to the path, and bring my spurs with you.’ And that the boy did.

They came to sit on the mound. They had hardly been there any time before they caught sight of the lady on horseback, coming along the same path, with the same apparel, at the same pace.

‘Ah, boy, I can see the lady on horseback coming!’ said Pwyll ‘Bring me my horse.’

Pwyll mounted his horse, and no sooner than he had done so, she had passed him by. He turned after her, and let his lively horse prance at its own pace. He guessed that he would catch her up on the second or third bound. [But] no nearer did he get to her than [any of the times] before. He spurred on the horse as fast as it could go. But he saw it was useless following her [in this way].

Then Pwyll spoke: ‘Maiden,’ he said ‘for the sake of the man you love the best, wait for me!’

‘Gladly I’ll wait’ said she ‘but it might have been better for the horse if you had asked me a good while before.’

The maiden stopped and waited and drew aside the part of her headdress that was there to cover her face. She looked him in the eye, initiating conversation with him.

‘Lady,’ he asked ‘where are you from? And where are you going?’

‘Going about my business’ said she ‘and glad I am to see you.’

‘And you are also welcome to me,’ said he.

And he realized at that moment the faces of every woman and girl he had ever seen were dull in comparison to her face.

Rhiannon – Illustrated by Alan Lee

The first time I read this passage, it was like a spell was cast over me, just as Rhiannon’s beauty overcame Pwyll in the tale.

Epona, in the guise of this otherworldly woman, has been in my thoughts ever since, and so beautiful goddess of horses has finally come into the Eagles and Dragons story as a mother and protector of Lucius and his elite group of horse warriors.

They will certainly need her in the battles to come…

Warriors of Epona (Eagles and Dragons – Book III) is out now!

To pique your interest, here is the synopsis of this new adventure with Lucius Metellus Anguis:

At the peak of Rome’s might a dragon is born among eagles, an heir to a line both blessed and cursed by the Gods for ages.

It is the year A.D. 208, and Emperor Septimius Severus’ legions are set to invade Caledonia in an effort to subdue the rebellious tribes north of Hadrian’s Wall once and for all.

Ahead of the legions, the emperor has sent Lucius Metellus Anguis, prefect of an elite force of Sarmatian cavalry, to re-establish contact with Rome’s old allies and begin waging bloody war on the rebel tribes. As the guerilla war rages on the edge of the highlands, the legions, the imperial court, and Lucius’ own family draw nearer to the front he was commanded to secure.

With the help of his horse warriors, can Lucius snatch victory from the chaos and blood of war? Can he keep the family he has not seen in years safe? As Lucius is drawn into a mysterious world of violence and despair, he discovers that his greatest enemy may well be the one within.

Find out if the Gods will turn their backs on Lucius, or if they will pull him out of the darkness before it is too late…

Roman Cavalry (Comitatus re-enactment group)

Stay tuned for Part II of The World of Warriors of Epona.

If you have not yet read any of the Eagles and Dragons novels, and if you want to get stuck in, you can start with the #1 Best Selling prequel novel, A Dragon among the Eagles. It is a FREE DOWNLOAD on Amazon, Apple iTunes/iBooks, and Kobo.

Thank you for reading.

Ancient Everyday: Medicus! – Physicians in the Roman Empire

Going to the doctor’s office is never something one looks forward to.

For most, myself included, it gets the heart rate and stress levels up to step into a building that’s full of ‘sick people’.

Sitting around in a waiting room with a group of scared, nervous, fidgety folks, is enough to drive you mad, and the sight of a white coat and stethoscope makes one want to run screaming from the building.

It was probably the same for our ancient Greek and Roman ancestors. Most civilians would have been loath to visit with a physician. It might not have been someone you wanted around, unless absolutely necessary.

‘Oh dear. That cough doesn’t sound good, my dear Septimius!’

Not so for the soldiers in the field.

I’m not an expert in ancient medical history, but I do know that the level of injury on an ancient battlefield would have been staggering. The sight or sound of your unit’s medicus would have been something sent from the gods themselves.

Imagine a clash of armies – thousands of men wielding swords, spears and daggers at close quarters. Then lob some volleys of arrows into the chaos. Perhaps a charge of heavy cavalry? How about heavy artillery bolts or boulders slamming into massed ranks of men?

Ancient surgical instruments, including forceps

It would have been one big, bloody, savage mess.

Apart from the usual cuts, slashes, and puncture wounds, the warriors would have suffered shattered bones, fractured skulls, lost limbs, severed arteries, sword, spear and arrow shafts that pushed through armour on into organs.

If you weren’t dead right away, you most likely would have been a short time later.

This is where the ancient field medic could have made the difference for an army. He would have been going through numerous patients in a short period of time. He would have had to decide who was a lost cause, who could no longer fight, and who could be patched up before being sent back out onto the field of slaughter.

The medicus of a Roman legion was an unsung hero whose skill was a product of accumulated centuries of knowledge, study, and experience.

Asklepios and Igia

Many of the physicians in the Roman Empire were Greek, and that’s because Greece was where western medicine was born. Indeed, the ancient Greeks had patron gods of health and healing in the form of Asklepios, Igeia, and sometimes Apollo.

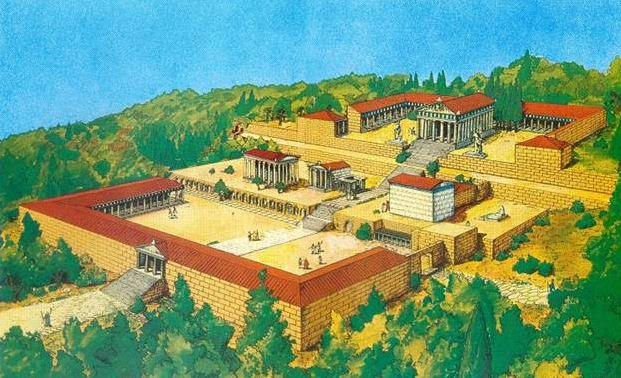

Artist rendering of the Asklepion of Kos

The greatest medical school of the ancient world was in fact on the Aegean island of Cos, where students came from all over the Mediterranean world to learn at the great Asklepion. Hippocrates himself, the 5th century B.C. ‘father of medicine’, was from Cos and said to be a descendant of the god Asklepios himself.

When it comes to Roman medicine, much of it is owed to what discoveries and theories the Greeks had developed before, but with a definite Roman twist.

Hippocrates

The fusion of Greek and Roman medicine in the Empire consisted of two parts: the scientific, and the religious/magical.

The more scientific thinking behind ancient medical practices is a legacy owed to the Greeks, who separated scientific learning from religion. The religious aspects of medicine in the Roman Empire were a Roman introduction.

Because of this fusion of ideas and beliefs, you could sometimes end up with an odd assortment of treatments being prescribed.

‘To alleviate your hypertension over your new business venture, you should take three drops of this tincture before you sleep. You should also sacrifice a white goat to Janus as soon as possible.’

Many Roman deities had some form of healing power so it depended on one’s patron gods, and the nature of the problem, as to which god would receive prayers or votive offerings over another. Amulets and other magical incantations would have been employed as well.

Roman surgical instruments

Romans had a god for everything, and soldiers were especially superstitious.

Greek medical thought rejected the idea of divine intervention, opting more for practicality in the treatment of wounds, and injuries; cleaning and bandaging wounds would have been more logical than putting another talisman about the neck.

All the gods were to be honoured, but in the Greek physician’s mind they had much better things to look after than the stab wound a man received in a Suburan tavern brawl.

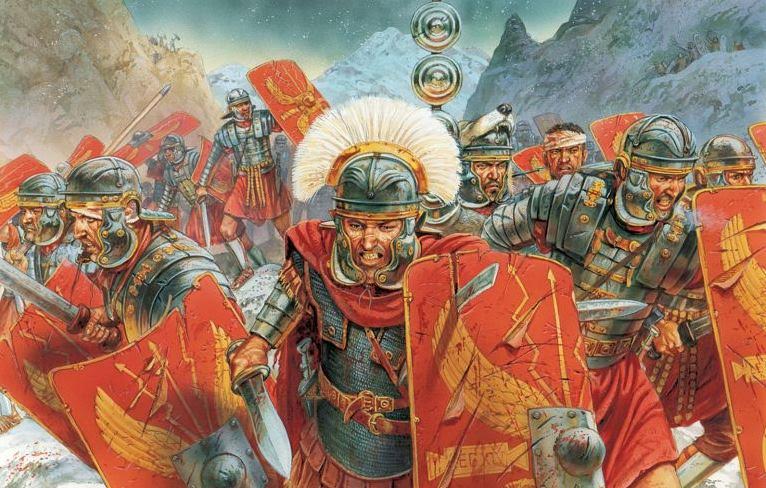

Roman Legionaries (illustrated by Peter Dennis)

For the battlefield medicus, things must have been much simpler than for the physician who was trying to diagnose mysterious ailments. They were faced mostly with physical wounds and employed all manner of surgical instruments such as probes, hooks, forceps, needles and scalpels.

Removing a barbed arrowhead from a warrior’s thigh must have required a little digging.

Of course, in the Roman world, there was no anaesthetic, so successful surgeons would have had to have been not only dexterous and accurate, but also very fast and strong. Luckily, sedatives such as opium and henbane would have helped.

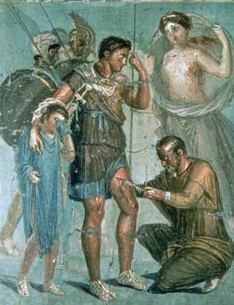

Medic helping a warrior tend a wound

When it came to the treatment of wounds, a medicus would have used wine, vinegar, pitch, and turpentine as antiseptics. However, infection and gangrene would have meant amputation. The latter was probably terrifyingly frequent for soldiers, many of whom would end up begging on the streets of Rome.

It is interesting to note that medicine was one of the few professions that were open to women in the Roman Empire. Female doctors, or medicae, would also have been mainly of Greek origin, and either working with male doctors, or as midwives specializing in childbirth and women’s diseases and disorders. When it came to the army however, most doctors would have been male.

Roman shears

Army surgeons played a key role in spreading and improving Roman medical practice, especially in the treatment of wounds and other injuries. They also helped to gather new treatments from all over the Empire, and disseminated medical knowledge wherever the Legions marched. Many of the herbs and drugs that were used in the Empire were acquired by medics who were on campaign in foreign lands.

Early on, physicians did not enjoy high status. There was no standardized training and many were Greek slaves or freedmen. This began to improve, however, when in 46 B.C. Julius Caesar granted citizenship to all those doctors who were working in the city of Rome.

This last point really hits home when it has become common knowledge that foreign doctors who come to our own countries today find themselves driving taxis or buses because they are not allowed to practice.

Modern governments, take your cue from Caesar!

Galen

One of the most famous physicians of the Roman Empire is Galen of Pergamon (A.D. 129-c.199). Galen was a Greek physician and writer who was educated at the sanctuary of Asklepios at Pergamon in Asia Minor.

After working in various cities around the Empire, Galen returned to his home town to become the doctor at the local ludus, or gladiatorial school. He grew tired of that work and moved to Rome in A.D. 162 where he gained a reputation among the elite. He subsequently became the personal physician of the Emperors Marcus Aurelius, Commodus, and for a short time, Septimius Severus.

Galen’s work and writings provided the basis of medical teaching and practice on into the seventeenth century. No doubt many an army medicus referred to Galen’s work at one point or another.

Galen is also an important character in A Dragon among the Eagles, the FREE prequel in the Eagles and Dragon series. In the book, Galen, an old friend and colleague of Lucius Metellus’ late tutor, presents Lucius with a choice that could well change the direction of Lucius’ life. In fact and fiction, Galen is a fascinating person of history.

Re-created ancient surgical instruments

I’ve but barely scratched the vast surface of this topic.

For some, there is this assumption that ancient medicine was somehow false, crude and barbaric. But modern western medicine owes much to the Greeks and Romans, civilian and military, who travelled the Empire caring for their troops and gathering what knowledge and knowhow they could.

The fusion of science, religious practice, and magic provides for a fascinating mix. In truth, medical practices in medieval Europe might have been more barbaric than in the ancient world.

Thank you for reading, and may Asklepios, Igeia and Apollo grant you good health!

12th century mural of Galen and Hippocrates in conversation

The Nine Muses – Creativity and the Higher Realm

And one day they taught Hesiod glorious song while he was shepherding his lambs under holy Helicon, and this word first the goddesses said to me – the Muses of Olympus, daughters of Zeus who holds the aegis: “Shepherds of the wilderness, wretched things of shame, mere bellies, we know how to speak many false things as though they were true; but we know, when we will, to utter true things.”

So said the ready-voiced daughters of great Zeus, and they plucked and gave me a rod, a shoot of sturdy laurel, a marvellous thing, and breathed into me a divine voice to celebrate things that shall be and things there were aforetime; and they bade me sing of the race of the blessed gods that are eternally, but ever to sing of themselves both first and last.

(Hesiod, Theogeny)

Hesiod

Sometime between the eighth and seventh centuries B.C. the poet Hesiod created his Theogeny, a work outlining the birth and genealogy of the Gods.

At the beginning of this epic poem, Hesiod talks about how, as a shepherd, he was caring for his flock on the slopes of Mt. Helicon, in the region of Boeotia. While there, Hesiod says that the Muses came to him and inspired him to create the Theogeny, a work that to this day provides the basis for ancient Greek religion.

Hesiod, before that, had not discovered his artistic self. He was a shepherd, the son of a farmer.

And yet, while on the slopes of this sacred mountain, the goddesses, the Muses, came to him and inspired him to bring forth his great work.

Mt. Helicon – 1829

Hesiod does not say he invented the contents of his work, or that he gathered existing tales from all over the Hellenic world.

The Gods gave him that song to sing. They inspired it in him, and he heard them.

We may scoff at this sort of thing today, our modern, media-driven minds too dense and distracted to hear anything beyond the ping of a mobile, but in the ancient world, and later ages of faith, the greatest artists and creators were those that paid attention to divine inspiration.

In the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, creativity and artistic endeavour were the realm of the Nine Muses, the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, or ‘Memory’.

Tell me, Muse, the story of that resourceful man who was driven to wander far and wide after he had sacked the holy citadel of Troy. He saw the cities of many people and he learnt their ways. He suffered great anguish on the high seas in his struggles to preserve his life and bring his comrades home. But he failed to save those comrades, in spite of all his efforts. It was their own transgression that brought them to their doom, for in their folly they devoured the oxen of Hyperion the Sun-god and he saw to it that they would never return. Tell us this story, goddess daughter of Zeus, beginning at whatever point you will.

(Homer, The Odyssey)

There is a wonderful book that every creative person should read and re-read. It’s called The War of Art, by historical fiction author, Steven Pressfield. The book is about doing the things that you love and were meant to do without giving in to any excuses, or ‘Resistance’, as Pressfield calls the artist’s enemy.

Whenever I read The War of Art, Pressfield reminds me of something that I forget from time to time.

Creativity should never be taken for granted.

If you feel that there is something creative you want to do, or be, it is your sacred duty to do or become that. When you feel those urges, you have to fight ‘Resistance’ and rationalization with all of your might so that you can bring those things you were meant to create to fruition.

Those urges are the Muses speaking to you, telling you it’s time. If you ignore them, it’s to the detriment of your own soul.

Because when we sit down day after day and keep grinding, something mysterious starts to happen. A process is set into motion by which, inevitable and infallibly, heaven comes to our aid. Unseen forces enlist in our cause; serendipity reinforces our purpose.

This is the other secret that real artists know and wannabe writers don’t. When we sit down each day and do our work, power concentrates around us. The Muse takes note of our dedication. She approves. We have earned favor in her sight.

(Steven Pressfield, The War of Art)

Homer and his Guide – William Adolphe Bouguereau 1874

In ancient eyes, those who ignored the Gods didn’t do too well.

Hesiod and Homer knew that it was their duty to honour the Muses, they knew that they could not have created the works that they did without the goddesses’ help. Hubris was not a good thing in the ancient world.

But it was not just Hesiod and Homer who called on these goddesses for help. Throughout history, some of the greatest poets and other artists did so too.

Tell me, Muse, the causes of her anger. How did he [Aeneas] violate the will of the Queen of the Gods? What was his offence? Why did she drive a man famous for his piety to such endless hardship and such suffering? Can there be so much anger in the hearts of the heavenly gods?

(Virgil, The Aeneid)

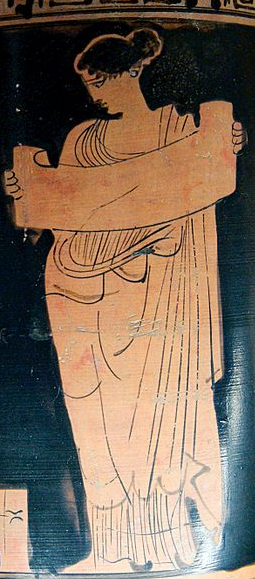

Praxiteles’ Hermes and Dionysos

The artist who called on the Muses for aid and blessing was the one that was listening.

We know of writers and poets who have called on the Muses in their work because they have been written down, but I imagine that painters and sculptors would have done so too. What might Praxiteles have done before he broke the surface of a piece of marble? Or Michelangelo before he put his brush to the ceiling of the Cappella Sistina? What went through Mozart’s head before the first heavenly notes of his Clarinet Concerto in A major came to him? Just listen to it…

Before an ancient singer breathed those first notes, or before the lyre player plucked that first string at the Panathenaea or the Pythian Games, you can be sure that some inner prayer, conscious or unconscious, was sent up to their own Muse.

Apollo

You can also be sure that for the artist whose heart was open to this, the Muses spoke back.

…and I alone was there, Preparing to sustain war, as well Of the long way as also of the pain, Which now unerring memory will tell. Oh Muses! O high Genius, now sustain! O Memory who wrote down what I did see, Here thy nobility will be made plain.

(Dante, Inferno)

But who were the Muses? Early traditions said there were three, but that eventually turned to nine, and that is the number that has been given for ages. Their leader was Apollo, the God of Art, Light and Prophecy, and in this particular capacity he was known as ‘Apollo Mousagetes’, or ‘Apollo Muse-leader’.

Each one of these goddesses was responsible for a particular art form, and so, individual artists may have called on certain Muses. The names of these goddesses and their assigned art are as follows:

Calliope – Epic Poetry

Clio – History

Erato – Lyric Poetry

Euterpe – Song and Elegaic Poetry

Melpomene – Tragedy

Polyhymnia – Hymns

Terpsichore – Dance

Thalia – Comedy

Urania – Astronomy

I will begin with the Muses and Apollo and Zeus. For it is through the Muses and Apollo that there are singers upon the earth and players upon the lyre; but kings are from Zeus. Happy is he whom the Muses love: sweet flows speech from his lips. Hail, children of Zeus! Give honour to my song! And now I will remember you and another song also.

(Homeric Hymn to the Muses and Apollo)

Some of the arts assigned to the Muses might not seem like ‘art’ to us today – I’m thinking of Astronomy and History in particular. However, to the ancients, this made perfect sense. Astronomy involved philosophy and the understanding of the Heavens; it required great imagination and thought.

Mnemosyne by Gabriel Dante Rosetti

And History? Well, to me that is ‘Mnemosyne’. History is the record of human achievement in all areas, including art. History, poetry, and storytelling go arm in arm.

It must have been a humbling experience for ancient artists to know that the Muses were looking over their shoulders as they carried out the work they were inspired to do.

It must also have been a wonder-full experience to feel that, to know that you were not alone.

My hope is that we have not totally lost this today – artists, writers, athletes, inventors, creators of all kinds will find themselves in what we call ‘The Zone’. Many will thank ‘God’ for their successes, they will be exhilarated after a good session.

As a writer, I know that when I sit down and have a fantastic writing time, even after the worst of days, there must be something more at work. I feel like I’ve had help that day. I feel like I have done justice to the art that I love, and for that, I am grateful.

If you are a creator of something, anything, it behoves you to acknowledge the help that you have had, especially if that help is Heaven-sent.

O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend The brightest heaven of invention! A kingdom for a stage, princes to act, And monarchs to behold the swelling scene!

(William Shakespeare, Henry V)

Thank you for reading.

Rewarding Sacrifice: What today’s world leaders can learn from Alexander the Great

Every year around this time, I try to write a post dedicated to the theme of Remembrance Day, something of a hat-tip to the service men and women who are scattered over the Earth trying to protect the world from itself.

After all, everyone one of my books deals with warriors, the struggle of war, and the changes war wreaks upon the fighters, their families, and the world around them. Eagles and Dragons Publishing’s #1 best selling book in 2016, A Dragon among the Eagles, is dedicated to men and women in service (and I mean that with utmost sincerity), and every year I attend my local Remembrance Day ceremony and think of all those who have laid down, or are currently risking their lives for the rest of us.

D-Day at Omaha Beach, Normandy

I think of my two grandfathers who fought in the World Wars as part of the British Army and Greek Merchant Navy respectively, and of my cousin who lost her husband outside of Kandahar more recently.

But is this enough of a tribute?

I don’t think so.

Frankly, I feel like anything I do or say or write, no matter how sincere and heartfelt it is, is not enough to be of sufficient thanks.

And I’m not talking about honouring war or the politicians who send men and women to war for their own selfish ends. I’m not going to sully this post with talk of political motives.

The troops are not responsible for the wars that happened in the past, or that are happening as we speak.

British Troops in Afghanistan

Sadly, we’ve seen a whole new generation of veterans emerge, people younger than you or I. When I was young, the word veteran was relegated to grandparents wearing poppies, or stories from history.

Not so anymore.

And we’ve a seen a resurgence of anti-war, pro-soldier art in the form of books, music, illustration, poetry, film and more. So much that seeks to honour the sacrifices being made.

Is it important to create these works of art?

Absolutely.

But again, is it enough?

I still don’t think so…

A new generation of troops

Let me say this now. I don’t have any answers. You won’t leave this post thinking, wow, he’s hit it on the head!

That is not my intent. But my hope is that we can all be a bit more aware and leave this post with some questions in our minds.

My original intent with this post was to rant about the lack of support for troops returning from various tours in the current hell-holes of the earth.

But ranting isn’t productive either.

WWII veterans visiting a cemetery in Normandy

In truth, when I started research for this post, I did some digging on-line for programs intended to support veterans and their families here in Canada, as well as in the USA and United Kingdom.

To my surprise, there are a lot of support systems in place.

That’s good, because veterans of any age are dealing with a tonne of shite that you and I can only imagine. Here are just a few:

-

extreme uncertainty

-

re-integration into civilian society

-

proper health care for injuries sustained in line of duty

-

PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder)

-

relationship difficulties

-

unemployment

-

homelessness

-

financial uncertainty and debt

That is a pretty heavy list, and there are a lot more that could be added to it.

The support that is out there is largely charity and foundation-driven. Many groups seem to be doing some outstanding work, and they do get some government support, but perhaps not enough.

Shouldn’t the people sending troops into danger do their utmost to help those same troops when they return home and are in crisis as a result of combat?

Alexander riding into battle at the head of his troops

This leads me to the title of this post: Rewarding Sacrifice: What today’s world leaders can learn from Alexander the Great

Whenever I think of the prime example of a true leader, I think of Alexander the Great.

Yes, I know many think of him as blood-thirsty tyrant, a maniacal conqueror, maybe even a selfish psychopath.

Whatever you think of Alexander the Great, however, you can’t deny that he shared in his soldiers’ hardships, and led by example. He inspired his troops to do what many thought was impossible, and after it all, including looming mutinies, they still loved him.

Alexander led from the front in every engagement, and when the battles were over, he knew how to reward his soldiers.

He knew that they had given everything to him, that they had been away from their families for years. They had fought and died, and Alexander, though disappointed with their grumblings at times, knew how to reward their sacrifices.

So what can world leaders learn from Alexander the Great?

What prompted this question was a passage I came across while doing some research for the (still ongoing) Alexander novels.

When Alexander’s army had crossed the Gedrosian Desert at the end of their long march to India, and they arrived at Opis, the troops, jealous of ranks given to Persians, threatened mutiny again.

Alexander delivered his famous ‘speech at Opis’ then, speaking to his disgruntled troops, not as the son of Zeus, or the new ‘Great King’, but as one of them. He could do this, and his words did move them, for he had shared their toils. If you would like to read the full speech in Arrian’s Anabasis, CLICK HERE.

But what we are concerned with here is not the mutiny, or the speech itself. It is how Alexander rewarded the veterans, those unfit for service due to old age and injury, or those unwilling to go further.

According to A.P. Dascalakis in his book Alexander the Great and Hellenism, Alexander:

“…had paid off all their debts, without asking how they had been contracted: they received high pay, besides what they seized as booty after every siege. Most of them had golden wreaths, as immortal guerdons of their valor and of honor from him. And if any died, their death was glorious, their burial splendid; bronze statues of most of them were set up in their towns, their parents were honoured and were exempt of all tax or levy.”

Think about some of that for a moment…and then think of the list of things troops returning home have to deal with after serving.

Canadian troops in Afghanistan

From what I can tell, there are support programs to help veterans with PTSD, injuries, and general health care, but we still hear a lot about veterans living on the streets, unable to afford a home, however small, or even get a job.

Some might say ‘Hey, a lot of other people are out there facing those same things!’, and that is true, but not everyone steps forward to defend their fellow citizens on the battlefield.

Alexander the Great honoured his soldiers with wreaths and statues and his love, but more practically, he paid off their debts, gave them good pensions, and rewarded their families by exempting them from taxation. He also ordered that soldiers’ children be given a proper education.

This got me to wondering…

If returning veterans did not have to worry about debt, taxation, homelessness, little to no pension, or further education for themselves or their children, they could focus more on the intense healing needed for them to deal with PTSD, health issues, new disabilities, and re-integration into the society which they had stepped up to defend.

Out of the trenches in WWI

I think Alexander the Great had it right. Give your veterans the rewards they deserve, commensurate with the sacrifices they have made.

I know this is more practical, but sometimes I’m guessing that is what’s needed.

Here are some crazy ideas Alexander the Great would approve, and that world leaders could implement for veterans:

-

Forgive all debts for veterans and their families so that they can have a fresh start

-

Give them boundless health care to overcome their wounds (mental and physical)

-

Ensure all vets get high-level pensions

-

Create legislation that forces all colleges and universities to provide free tuition for veterans and veterans’ children

Some of this may already be done in some countries, but I suspect most not.

Does this mean higher taxes for the rest of us civilians?

Likely, yes. But these are things that I think we can do for those who put themselves on the line for the rest of us.

Greek Resistance fighters in WWII

Call me naïve and idealistic, but with everything else vets are dealing with, money worries should not be among them.

As I said before, I don’t have all the answers, and I don’t know about all the programs for veterans and their families that are out there.

Here are a few that I know of and which I came across while researching this post:

In Canada:

Vets Canada

Veterans Transition Network

Wounded Warriors Canada

Veterans Affairs Canada

In the United Kingdom:

Veterans Aid

Veterans’ Foundation

Royal British Legion

Veterans UK

In the United States:

Disabled Veterans National Foundation

Veterans Support Foundation

United States Veterans Initiative

US Department of Veterans Affairs

If any of you know of some particularly helpful charities or programs in the country where you are, please do share the information in the comments below. You never know who will be reading and whether something here might help.

Also, if you haven’t heard about Theatre of War, you may want to check out this post on healing PTSD with ancient Greek tragedy. PTSD was a condition that afflicted ancient warriors as well as modern ones, and this particular theatre group has been making great headway in helping veterans to cope with PTSD. CLICK HERE to check it out.

As for what us civilians can do, it may not be enough, but every little must help.

Pin a poppy on your jacket, donate to a veterans’ charity, go to a ceremony, write a blog post, shake a vet’s hand, say thank you to a veteran.

It’s all better than doing nothing, lest we forget…

Thank you for reading

This year, Eagles and Dragons Publishing is happy to make a donation to Wounded Warriors Canada and their COPE program which provides therapy to military families dealing with PTSD.

Ancient Everyday – Garum: MSG of the Roman World

Here is lordly garum, a costly gift, made from the blood

of a still-gasping mackerel

(Marcus Valerius Martialis)

If you are a fan of the Roman Empire, or read any fiction or non-fiction about Roman civilization, chances are you will come across a certain salty condiment that many ancients went mad for.

In this edition of Ancient Everyday, we’re going to look at garum.

Now, let me say this: I’m not a big fish-eater.

Yes, I know, I’m half island Greek and don’t all Greeks love to eat fish?

Not this one.

So let me tell you that when I first found out what garum was, what it was made of, I had a titanic wave of nausea wash over me.

But whereas garum would have had me running, most Romans across the Empire loved this stuff!

So, as this is supposed to be an educational piece, I shall set aside my disgust and press on in the interests of history.

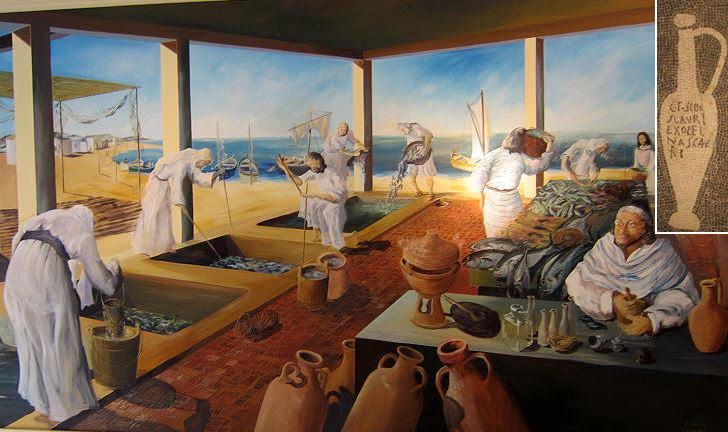

A Roman Banquet – spot the hints of garum!

So, what exactly is garum?

Basically, it is fermented fish sauce that was used as a condiment on just about anything. It was created from fish intestines and other parts mixed with salt.

It was immensely popular and supposedly quite healthy in that it was packed with protein, amino acids, minerals and vitamin B.

It was also rich in monosodium glutamate. That’s right…MSG!

Many of you will know MSG as a long-standing chemical compound used in modern food flavouring. It’s been called a ‘silent killer’, and linked to adverse health effects including something called ‘Chinese restaurant syndrome’.

Fish bits used to make garum

Now I don’t know if the Romans experienced anything like garumitis (today’s made-up word), and that doesn’t really matter here. What we need to know is that Romans put it on everything from seafood and chicken, to olives, porridge and more. It was the food seasoning of choice for those who could afford it.

They couldn’t get enough of garum!

Here is Pliny the Elder, the famed natural historian, speaking about garum:

Another liquid, too, of a very exquisite nature, is that known as “garum:” it is prepared from the intestines of fish and various parts which would otherwise be thrown away, macerated in salt; so that it is, in fact, the result of their putrefaction. Garum was formerly prepared from a fish, called “garos” by the Greeks; who assert, also, that a fumigation made with its head has the effect of bringing away the afterbirth.

At the present day, however, the most esteemed kind of garum is that prepared from the scomber, in the fisheries of Carthago Spartaria: it is known as “garum of the allies,” and for a couple of congii we have to pay but little less than one thousand sesterces. Indeed, there is no liquid hardly, with the exception of the unguents, that has sold at higher prices of late; so much so, that the nations which produce it have become quite ennobled thereby. There are fisheries, too, of the scomber on the coasts of Mauretania and at Carteia in Bætica, near the Straits which lie at the entrance to the Ocean; this being the only use that is made of the fish. For the production of garum, Clazomenæ is also famed, Pompeii, too, and Leptis; while for their muria, Antipolis, Thurii, and of late, Dalmatia, enjoy a high reputation.

(Pliny the Elder, Natural History 31.43)

Artist impression of a garum factory

After the garum liquid was extracted, the macerated remains, a pulp called allec, was used by the poorer classes, those who could not afford garum, to flavour their porridge – a grisly tapenade of sorts.

FYI – I prefer maple syrup on my porridge.

Garum production and export was a BIG industry in the Roman Empire, with production centres, a system of distribution by land and sea, amphora marked by the producer etc. etc.

It was also a smelly industry, for obvious reasons, so garum factories were often located outside of cities.

Garum amphorae

Just as with wine and olive oil, there were different grades of garum that were priced accordingly, as Pliny alludes to in the quote above.

Not all gara were created equal, and there were different recipes from different ports. The best was said to be from the Iberian Peninsula, in Hispania, particularly from Carthago Novo (Cartagena), and Gades (modern Cadiz in Andalusia).

Ruins of a garum factory in Spain

Different fish were used in garum too, depending on the company, recipe, and place where it was made. Some of the most common were mackerel, anchovies, sprats, sardines, tuna, and even shell fish. Archaeology has also revealed the production of kosher garum among Roman Jews.

You might think that every person in the Empire loved garum, but not everyone was a fan, including Seneca, whose family was from Hispania:

What? Do you suppose that those oysters, a sluggish food fattened on slime, do not weigh one down with mud-begotten heaviness? What? Do you not think that the so-called “Sauce from the Provinces,” the costly extract of poisonous fish, burns up the stomach with its salted putrefaction? What? Do you judge that the corrupted dishes which a man swallows almost burning from the kitchen fire, are quenched in the digestive system without doing harm? How repulsive, then, and how unhealthy are their belchings, and how disgusted men are with themselves when they breathe forth the fumes of yesterday’s debauch! You may be sure that their food is not being digested, but is rotting.

(Seneca, Ad Lucilium Epistulae Morales 95.25)

Seneca seemed like a rather more health-conscious person, so, perhaps like people today who ask for their Chinese food without MSG, he was aware (or disgusted by) the adverse effects of consuming too much of the over-pricey liquid that Pliny believed was “exquisite in nature”.

I suppose the tastes of the people in the Roman world were as vast and varied as the Empire itself.

Modern garum

For myself, I’ll give garum or its modern equivalent a miss, but that’s not to say people don’t go in for it today. Maybe you do as well?

Thank you for reading!

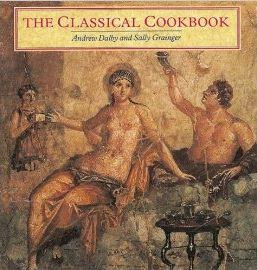

If you are curious about an ancient recipe that uses garum, and you want to try it out, the Classical Cookbook has a few. Here is one by Apicius for soft-boiled eggs (page 117) that you may want to try.

Ingredients:

– 4 oz pine kernels, soaked overnight in white wine

– 1 teaspoon chopped fresh lovage or celery leaf

– 1 tablespoon of Garum (Fish Sauce)

– 1 tablespoon of honey

– 1 tablespoon of white wine vinegar

– ½ teaspoon of ground black pepper

– 4 soft-boiled eggs

Strain the pine kernels and pound or process them to a smooth paste. Add the lovage, fish sauce, honey, vinegar and pepper and continue to pound or process until you have a smooth mixture. Finish the dish as if you were making egg mayonnaise and garnish with cucumber.

Bon appétit! Or rather, Bene sapiat!

Samhain at the Gates of Annwn

It’s the end of October, and as it is the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain I thought it would be a good idea to look a place that is both mysterious and iconic: Glastonbury Tor.

To most, the mere mention of Glastonbury will likely conjure images of wild, scantily clad or naked youths and aged hippies. You’ll think of thousands of people covered in mud as they wend their way, higher than the Hindu Kush, among the tent rows to see their favourite artists rock the Pyramid Stage.

It’s a great party, but to me that’s not the real Glastonbury.

This small town in southwest Britain is an ancient place. The real Glastonbury is a place of mystery, lore and legend. It is a place that was sacred to the Celts, pagan and Christian alike, Saxons, and Normans. For many it is the heart of Arthurian tradition, and for some it is the resting place of the Holy Grail.

Today, Glastonbury is a place where those seeking spiritual enlightenment are drawn. The New Age movement is going strong there, yet another layer of belief to cloak the place.

I lived in the countryside outside of the town for about 3 years and I never tired of walking around Glastonbury and exploring the many sites that make it truly unique.

From where I lived on the other side of the peat moors, I awoke every morning to see Glastonbury’s majestic Tor shrouded in mist.

My morning view of the Tor across the Somerset levels

Tor is a word of Celtic origin referring to ‘belly’ in Welsh or a ‘bulging hill’ in Gaelic. Glastonbury Tor thrusts up from the Somerset levels like a beacon for miles around. Every angle is interesting. On the top is the tower of what was the church of St. Michael, a remnant of the 14th century. Before that, there was a monastery that dated to about the 9th century A.D.

However, habitation of this place goes much farther back in time with some evidence for people in the area around 3000 B.C. But it was not always a religious centre. In the Dark Ages, the Tor served a more militaristic purpose and there are remains from this period.

In Arthurian lore, the Isle of Avalon is a sort of mist-shrouded world that is surrounded by water and can only be reached by boat or secret path. In fact, during the Dark Ages and into later centuries, until the drainage dykes were built, the Somerset levels were prone to flooding. This flooding made Glastonbury Tor and the smaller hills around it true islands. With the early morning mist that covers the levels, this watery land would have been a relatively safe refuge for the Druids, and early Christians, Dark Age warlords and late medieval monks.

The Tor surrounded by flooded levels – Avalon!

In Celtic myth, Glastonbury Tor is said to be the home of Gwynn ap Nudd, the Faery King and Lord of Annwn, the Celtic otherworld.

Gwynn ap Nudd is the Guardian of the Gates of Annwn. He is an Underworld god. It is at Samhain that the gates of Annwn open. This was also the place where the soul of a Celt awaited rebirth. (Quick hint: We delve into this in the upcoming Eagles and Dragons novel, Warriors of Epona!)

If you are on the Tor at Samhain, you may hear the sound of hounds and hunting horns as the lord of Annwn emerges for the Wild Hunt of legend.

The Wild Hunt 1872 by Peter Nicolai Arbo

In Arthurian romance, there is a tradition of the wicked Melwas imprisoning Guinevere on the Tor. Arthur rides to the rescue, attacks Melwas and saves Guinevere. This particular story mirrors an episode in Culhwch ac Olwen, one part of the Welsh Mabinogion, in which Gwythyr ap Greidawl attempts to save Creiddylad, daughter of Lludd, whom he is supposed to marry, from Gwynn ap Nudd himself.

Another even more fascinating Arthurian connection can be found in a pre-Christian version of the ‘Quest of the Holy Grail’, called the ‘Spoils of Annwn’ which was found in the ‘Book of Taliesin’. In this tale, Arthur and his companions enter Annwn to bring back a magical cauldron of plenty. In this, some say that ‘Corbenic Castle’ (the ‘Grail Castle’) is actually Glastonbury Tor. It isn’t just Herakles and Odysseus who journeyed to the Underworld!

Glastonbury Tor is not only associated with Celtic religion, myth and legend. It is also said by some to be a place of power or a sort of vortex in the land that lies along some of the key ley-lines, including what is called the St. Michael ley-line. The majority of sites associated with St. Michael, the slayer of Satan, along the ley-line were indeed places of power and belief of the old religion.

But this is nothing new. Christians built on top of sites sacred to the pagans they were eager to overcome. What better way to symbolize your ‘victory’ than to build right on top of a site and make it yours.

‘Gates of Annwn and Gwynn ap Nudd? Let’s build a church of St. Michael on top of it! That’ll show ‘em!’

Artist impression of Gwynn ap Nudd at the hunt

But myth and legend persist through story and place, and the Tor is a prime example of how successive traditions do not overcome each other, but rather combine to make up the various aspects of that place.

If you ever get to Glastonbury, the Tor is a definite must. Walk to the top and sit awhile. Look out over the landscape and watch the crows and magpies dive in the wind around the steep slopes. Close your eyes and listen. While you’re there, you can decide whether you are sitting on a natural formation, a ceremonial labyrinth, a hill fort, a sleeping dragon, the mound where Arthur sleeps until he is needed once more, or the doorstep of the Gates of Annwn itself! The Tor is all of these things and more.

However, no matter what you believe, one thing is certain: Glastonbury Tor remains a site of extreme beauty and mystery that is well worth a visit, even if it is just to watch the sun sink in the West.

Have a safe and happy Samhain.

The World of Killing the Hydra – Part V – Desert Legion: The Fortress of Lambaesis – Imagining Saharan Frontier Life

What was it like to live on the very edge of the Roman Empire?

When writing Killing the Hydra, this was something I asked myself many times. What was life like for soldiers, commanders, women, children, and locals under Roman rule? What was it like to be so isolated in a place that, for many, sat on the precipice of the known world?

The Numidian Desert – the Sahara in modern Algeria

In this fifth and final part of The World of Killing the Hydra, we’re going to look at the place where Lucius Metellus Anguis is posted to, and where his family joins him – the legionary base at Lambaesis.

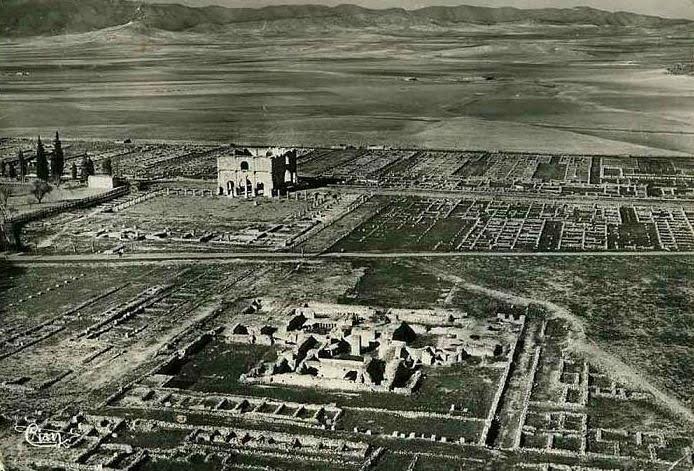

Lambaesis was located in the province of Numidia (modern Algeria), and was the base for the III Augustan legion at the beginning of the third century A.D. when this story takes place. Lambaesis was established by Emperor Hadrian between A.D. 123-129 when the III Augustan legion moved there.

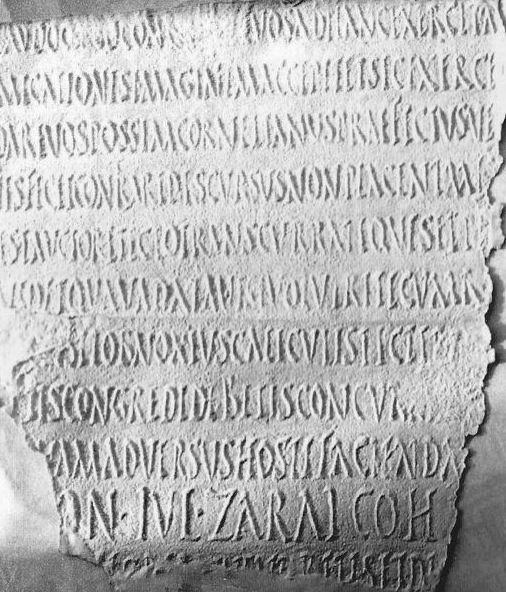

Hadrian toured the Empire and on his visit to Lambaesis, he addressed the troops of this desert legion. Evidence of this address has come down to us in the form of a pillar inscription that was located on the large outdoor parade ground of the base.

Part of the inscription from Lambaesis documenting Hadrian’s address to the troops when he visited there.

The III Augustan legion, however, was older than that. It originated under Pompey the Great in the civil war against Julius Caesar and was eventually moved to North Africa in 30 B.C. by Octavian (who became Augustus) after his victory over Mark Antony.

Eventually, the III Augustan came to be based at Lambaesis, one of only two Roman legions in North Africa, the other being based in Aegyptus.

The III Augustan played an important role in the security and urbanization of North Africa, helping to build roads, aqueducts, fortifications, theatres and more. This work in turn connected towns and cities, facilitated trade, and provided protection for outlying settlements. The work of the army engineers and surveyors brought Roman civilization to this remote frontier.

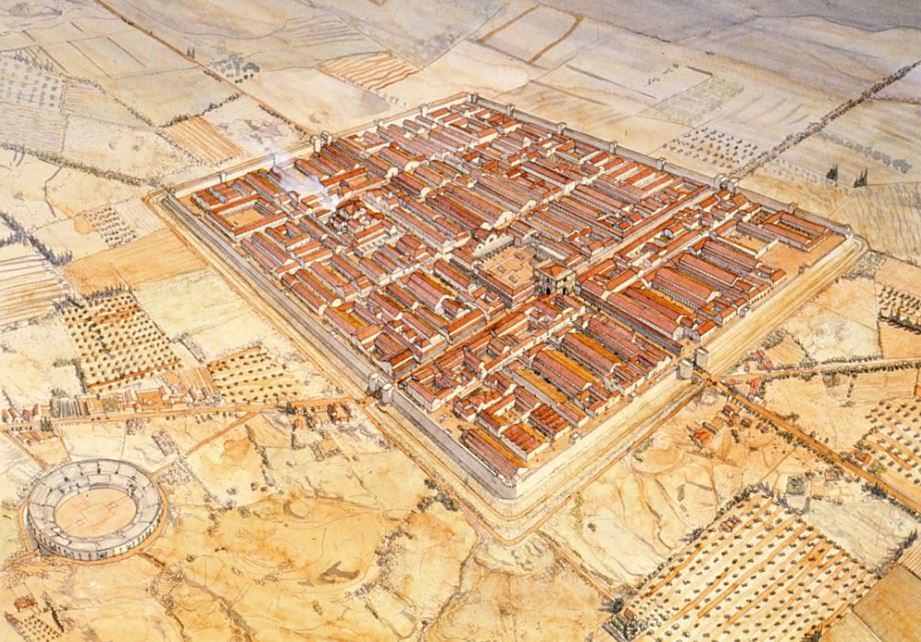

The Praetorium of Lambaesis

The III Augustan was a veteran legion, and of the remains present in that place, apart from the arches of Septimius Severus and Commodus, temples, baths and cemeteries, the principia with its open courtyard is the most stunning of its remains.

This base was on the edge of the deep desert in modern Algeria, backed by the Aures Mountains. At first glance, this seems to have been a lonely windswept place, just as it is today. However, during the Roman period, Lambaesis would have been a busy, thriving place.

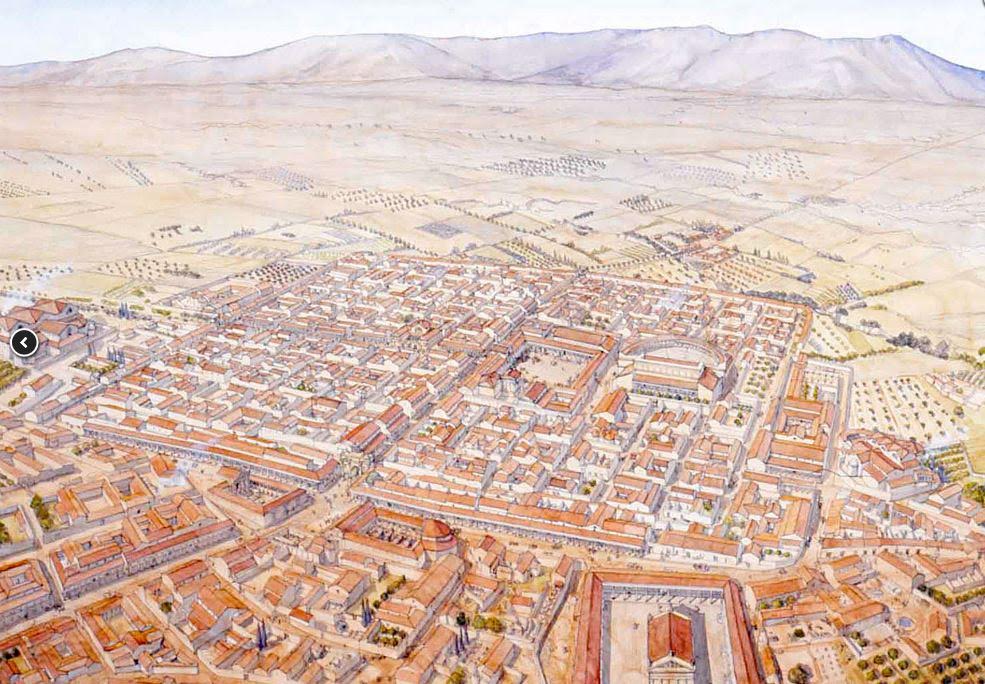

Artist impression of Lambaesis by Jean Claude Golvin

This was not so much an active frontier like that of the Danube or Parthian fronts, but rather a more peaceful place, punctuated with occasional incursions by Garamantians, nomadic Berber tribes and others.

For the most part, the veterans of the III Augustan took part in public building works and improvements, as well as patrols. The men of the legions were a part of society at Lambaesis and the surrounds.

Previously, men of the legions were not permitted to marry, but this law was changed under Septimius Severus, and so many men would have had families living in the vicus outside the base’s walls, or in some instances within the walls.

Add to this the presence of the large, prosperous colonia of Thamugadi, just seventeen miles away, and you have a frontier that was busy, social, and economically vibrant.

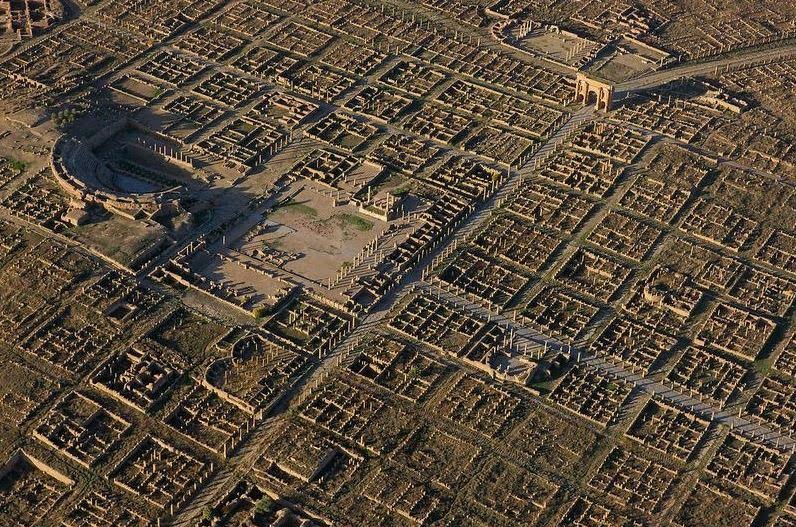

Aerial view of the colonia of Thamugadi

The colonia of Thamugadi was where veterans of the III Augustan legion retired to once their military service was at an end. It was founded by Emperor Trajan in about A.D. 100 under the name of Marciana Traiana Thamugadi. It was a walled settlement, but not fortified, and had a population of about 15,000.

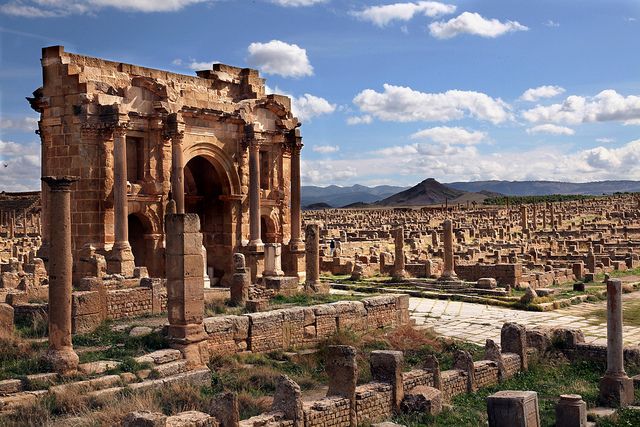

Today, it is made up of some of the most intact and vast ruins of Roman North Africa, including the well-preserved arch of Trajan. It had twelve public baths, theatres, a public library, a basilica and a magnificent temple of Jupiter.

The arch of Trajan in Thamugadi

One imagines that it was lonely for soldiers’ wives and their children, being posted to such a remote location, compared with other parts of the Empire, but with the changed laws regarding marriage for troops, the close proximity of Thamugadi to Lambaesis, and the thriving economy of Roman North Africa at this point in time, it seems like Saharan frontier life may not have been the sort of lonely, wasteland existence that I had in mind when I started my research and writing.

I always try to travel to the places I am writing about, but sometimes that just isn’t possible, or safe. Lambaesis was one of those places.

At the time of my Tunisian research for Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra, we were told there was a travel ban to Algeria where the remains of both Lambaesis and Thamugadi are located.

Artist impression of Thamugadi by Jean Claude Golvin – this was not a tiny village, but a bustling settlement!

Our 4X4 skirted the military border between the two countries, distant guard towers and barbed wire visible as a long grey line cutting across the North African landscape.

We asked our guide if we could drive into Algeria but he was adamant that it wasn’t possible. “No chance. It is forbidden. They will shoot at us,” he said.

I don’t know if that was true or not, but some things are not worth the risk. After all, we have the internet now and a myriad of resources on-line.

So, we had to settle for pulling our truck over on the gravelly roadside and gazing westward across the guarded border to the Aures Mountains of Algeria and imagining what remnants of Rome lay scattered in that vast expanse.

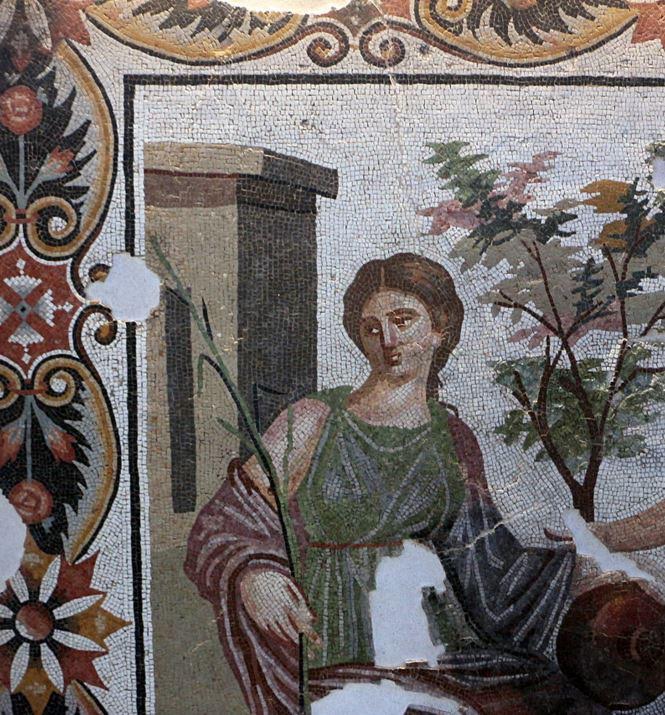

Mosaic fragment from Lambaesis

The light was dull that day, an iron-grey winter sky, so the feeling of loneliness and desolation was acute. Somewhere out there was the base of the veteran III Augustan legion. There was a colonia for veterans filled with the amenities of Roman civilization.

This was a land where my character was to be posted, along with his family, and the families of his fellow officers and troops. Many would have had family and friends in Thamugadi, done business there, and used the network of roads that really did, in one way or another, lead back to Rome…

It was hard to imagine as I stood there with the dust whipping around us, our guide looking nervously in our direction as if we might attempt something stupid.

The relief on his face when we said “OK. Let’s go.” was darkly comic. It was also real.

But maybe that hints at Saharan frontier life in the Roman Empire?

Aerial view of Lambaesis

Despite the fact that this was not one of the most active (militarily) fronts of the Empire, or that Roman civilization was indeed present and thriving in this remote place far from the heart of the Empire, Lambaesis was nevertheless a place of war, a place of danger, a place where one could not let one’s guard down. When war was not being waged, there were still battles to be fought on the political front, and enemies lurking in the shadows.

History has taught us that complacency can lead to trouble, and in the Roman Empire this was a fact of life.

Will Lucius Metellus Anguis come out of it alive? Will he be able to protect his family in that remote corner of the world?

Well, you would have to read the book to find out.

I hope you have enjoyed this series on The World of Killing the Hydra.

Writing this book was a fantastic adventure that took me to places I never expected to reach, but which are endlessly fascinating. If you read it, I do hope you enjoy it.

And if you missed any of the posts in this blog series, you can read the full set of blog posts by CLICKING HERE.

If you have not yet read any of the Eagles and Dragons series books, remember you can always get the first book, A Dragon among the Eagles, for FREE. Just CLICK HERE.

Thank you for reading.

The World of Killing the Hydra – Part IV – Horse Warriors: The Sarmatians

In this fourth installment of The World of Killing the Hydra, we’re going to look at a group of warriors who also have ties to myth, and who, as a fighting force, became legendary in the Roman world.

We are, of course, going to talk about the Sarmatians.

In Killing the Hydra, Lucius Metellus Anguis finds himself getting to know the men of the cavalry ala of Sarmatians who have been sent to join the III Augustan Legion at Lambaesis, in Numidia.

Artist impression of Sarmatian Cavalry

The leader of this fighting force is Mar, a king of his people who led them against Rome in the wars with Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Mar is joined by his royal nephew, Dagon, and both men play a key part in the story.

But who were the Sarmatians?

The average person has not heard about this group of warriors that came to form the elite heavy cavalry of the Roman Empire. Most people probably know of them only from the role they play in the movie King Arthur, with Clive Owen.

Researching Sarmatian warrior culture was a fascinating part of the research for Killing the Hydra.

The Sarmatians were a Scythian-speaking people from north of the Black Sea, and the high point of their civilization spanned from the 5th B.C. to the 4th century A.D. when they eventually went into decline because of pressure from the Huns and Goths.

Lance head of a Sarmatian ‘contos’, a 16 foot lance

The Sarmatians were a nomadic Steppe culture whose lands extended from the Black Sea to beyond the Volga in western Scythia.

Herodotus believed the Sarmatians (or ‘Sauromatae’) were descended from intermarriage between Scythian men and Amazon women, and that ever since the two peoples joined:

“the women of the Sauromatae have kept their old ways, riding to the hunt on horseback sometimes with, sometimes without, their men, taking part in war and wearing the same sort of clothes as men… They have a marriage law which forbids a girl to marry until she has killed an enemy in battle; some of their women, unable to fulfill this condition, grow old and die unmarried.”

(Herodotus, The Histories, Book IV)

Indeed Sarmatian grave discoveries have revealed armed women warriors, so it seems likely that such tales would easily have given rise to the Greek perception that the Sarmatians were descended from the Amazons, those beautiful and terrible daughters of Ares.

Amazons in battle

In Killing the Hydra, Mar, in conversation with Lucius, relates to the young Roman how the women of their people also fought:

“The women of our land are brave souls. We do not lock them up before the hearths of our homes. They are free to ride with us and wield the sacred sword. Some are priestesses and others have been gifted by our gods with foresight. Sarmatian women are nobler than what your Latin word ‘noble’ implies.”

(Mar, in Killing the Hydra)

And what of the men? Sarmatian men were fierce warriors and skilled horsemen, and according to the Roman writer Ammianus Marcellinus, they:

“…have very long spears and cuirasses made from smooth and polished pieces of horn, fastened like scales to linen shirts; most of their horses are made serviceable by gelding, in order that they may not at sight of mares become excited and run away, or when in ambush become unruly and betray their riders by loud neighing. And they run over very great distances, pursuing others or themselves turning their backs, being mounted on swift and obedient horses and leading one, or sometimes even two, to the end that an exchange may keep up the strength of their mounts and that their freshness may be renewed by alternate periods of rest.” (Ammianus Marcelinus, Roman History, Book XVII)

A Sarmatian crown

Sarmatian art and culture is also very rich.

Animal imagery was common in their artwork and often included such totem animals as dragons, griffins, eagles, sphinxes, snake women, and of course, horses. Often, these images were tattooed on their bodies.

The characters of Mar and Dagon are naturally curious about the dragon imagery on Lucius’ armour and weapons. They see it as a sign.

Also, if you remember the Sibyl’s prophecy from Children of Apollo, you will know that Lucius’ meeting with the Sarmatians is no coincidence.

The Sarmatians take their gods very seriously, but the one they most revered was their war god who was represented by the Sacred Sword.

Sarmatian Warriors on

Trajan’s Column

The Sarmatians’ favourite trial of strength was single combat.

They believed that there was mystical power in battle, and when they defeated their enemies, it’s said they often took the heads, scalps, and beards of the vanquished, drinking blood from the skulls of the slain.

Ancient cultures often did have what we might perceive as barbaric rituals, but it’s sometimes difficult to detect truth in the midst of Greek and Roman propaganda or storytelling.

The picture painted does make for a wonderfully colourful group of warriors.

Despite the tales of fighting women, magic swords, scalping, and the drinking of blood, there is one fact that remains certain – the Sarmatians were some of the best cavalry the world had ever seen.

They were sometimes known as ‘lizard people’ because of their scale armour which covered both the horse and rider almost completely.

The Sarmatians were heavy cataphracts, the shock troops that were used to ride down the enemy while wielding their long swords, and the contos, a lance of about five meters, or sixteen feet long.

Artist impression of a

Draconarius carrying a Draco

The image that the Sarmatians are probably most known for, however, is the draconarius.

This was their war standard which they carried into battle. It consisted of a bronze dragon’s head with a long wind sock attached to it. It was held on a pole and carried at a gallop. When the wind passed through the draco, it made a loud howling sound that was said to terrify the enemy.

The draco was adopted as a standard by all Roman cavalry in the 3rd century A.D.

It’s amazing that, as a highly disciplined fighting force, the Sarmatians remained active for as long as nine centuries.

When Marcus Aurelius won a decisive victory over the Sarmatians in A.D. 175, he obtained an elite heavy cavalry for Rome that would make the auxiliaries much more of a force to be reckoned with.

Coin of Marcus Aurelius showing Sarmatian captives

As ever, the Romans knew a good thing when they saw it.

In the aftermath of Rome’s victory, Marcus Aurelius obtained 8000 heavy Sarmatian cataphracts which became the most skilled cavalry of the age.

It is these warriors, descended from the Amazons and mighty Scythians of the Steppes, who now step into The World of Killing the Hydra.

Mar, Dagon, and their warriors turn the tides of war against the nomads in Numidia, and become an important new force in the life of Lucius Metellus Anguis.

Draco standard

The Dragons are now in the thick of it with the Eagles of Rome.

Thank you for reading.

The World of Killing the Hydra – Part III – Thugga: Walking through a Roman Ghost Town

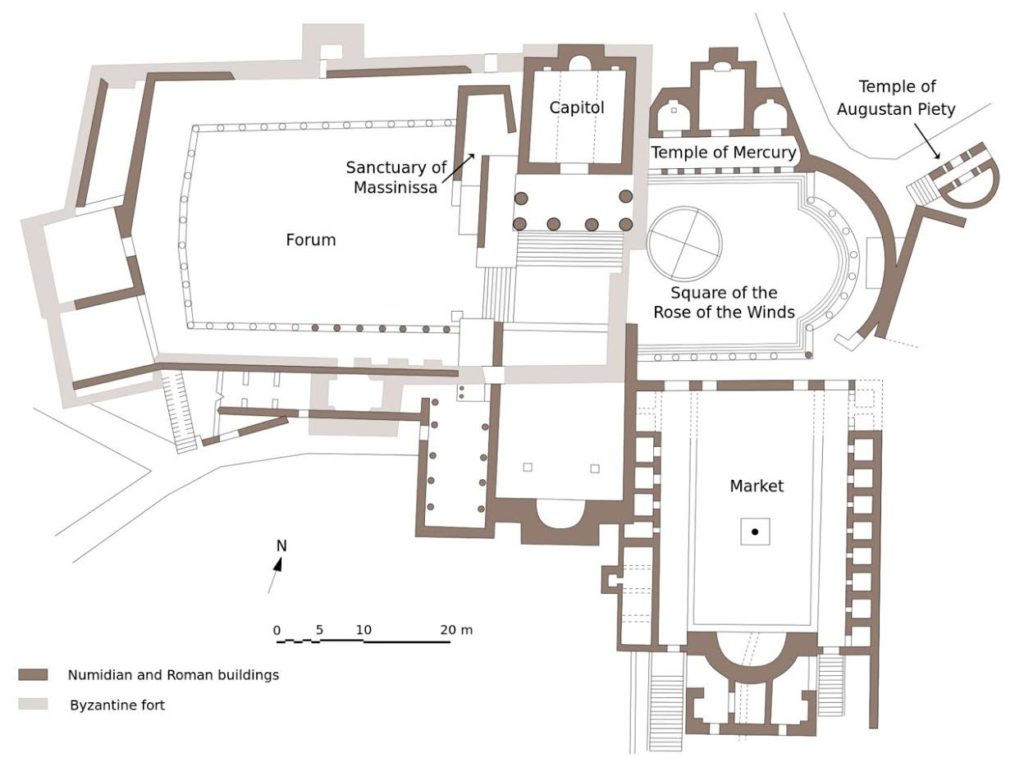

We’re heading back into the province of Africa Proconsularis this week with a brief look at one of the best preserved ‘small towns’ of Roman North Africa – Thugga.

I visited Thugga (also spelled ‘Dougga’) a few years ago, when I was doing research in Tunisia for Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra.

I was with a small group that headed out in two 4x4s from the ruins of Carthage, south to Thysdrus (El Jem), across the great salt plains of Chott El Jerid and into the soft, sand-seas of the Sahara.

When we turned north again, skirting the edge of the guarded Algerian border, we came once more into the lush plains of northern Tunisia where grey mountains sprout from green, olive-dotted valley floors, and where low clouds hovered comfortably around their peaks in what was the mildest January I’ve ever experienced.

The countryside was beautiful and lonely, and I missed the desert dunes very much by that point, our time in the South having been all-too-short.

Countryside of Northern Tunisia

Admittedly, I had not heard of our next destination, ‘the place of Dougga’ as our guide called it. Our truck pounded along the winding, potted roads, climbing higher and higher, the land getting greener by the mile.

I also had a fever at this point in the journey, the result of having opted for what I thought was boiled soup, rather than camel meat a couple nights before.

Quick tip: they don’t boil the soup, and eating it is equivalent to drinking a murky glass of Saharan tap water.

A public latrine in Thugga

Nevertheless, the historian in me could not help but spot the distant ruins perched on a hillside in the distance. As we came closer, and the road got rougher, it became apparent that there was much more to ‘the place of Dougga’ than we had been led to believe.

The sprawling remains of Thugga

This wasn’t a small gathering of weathered ruins – it was a city! Or rather, it felt as such in that lonely, windswept place.

I stepped out of the truck, grateful that the ‘Couscous Beats’ soundtrack our driver had been torturing us with since the beginning of the trip finally stopped. Everything was quiet, but for the wind, and the crunch of gravel beneath our feet as we approached the small, shuttered kiosk.

When I saw no one was there, I wondered if we would be able to get in, and craned my neck to try and see the tantalizing view beyond the gates.

From the side came a man with a shot gun slung over his shoulder. We had just woken him from his obviously important duty. He smiled however, and spoke in hushed tones with our guide who evidently knew the man, or appeared to know him.

Our man turned to us and nodded. “You have one hour,” he said, and the gates opened.

One of the main streets of Thugga

I’m not going to go into the history of Thugga a great deal here – there is an uncharacteristically good Wikipedia page on this site which you can read by CLICKING HERE.

But, before we walk the streets of this Roman ghost town, there are a few things worth mentioning.

Thugga has had a long a varied history of settlement, having gone from its origins as a Numidian-Berber settlement, to a place under Punic control during the ages of Carthaginian hegemony, to a major Roman town, and finally under Byzantine control prior to Arab dominance in the region.

In the first century B.C., the Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus mentioned the “beautiful enormity” of Thugga.

The Forum of Thugga

It is a big site – about sixty-five hectares (about 161 acres) – which makes it surprising that Thugga is considered a ‘small’ Roman town. Its population when it was at its most prosperous in the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D. is said to have been about five thousand residents.

UNESCO made it a World Heritage Site in 1997, and cited it as the “best preserved Roman small town in North Africa”.

Thugga was a thriving settlement because of agriculture, its location on the fields of northern Tunisia ideal for crops. But its fortunes took an even better turn in A.D. 205 when it was made a municipium by order of Septimius Severus and his son, Caracalla, acquiring the title of Municipium Septimium Aurelium Liberum Thugga. After that, Thugga received more rights and freedoms, and magistrates of the town were made Roman citizens.

Thugga didn’t enjoy the imperial favour that Severus’ hometown of Leptis Magna did, but it did prosper under Severus, aided by the fertile landscape that surrounded it, olives, oil, and grain being key to the running of the Empire.

Theatre of Thugga

I didn’t know any of this however, as I stepped through the gate of the archaeological site and entered the labyrinthine streets of Thugga as our guide settled himself beneath an olive tree and left us to our own devices.

One hour was not nearly enough time!

Our small group quickly broke apart as people set about exploring the site with confidence, as if they were walkers in some sort of past-life recollection, certain of where they needed to go.

For myself and my friend, it was more a feeling of overwhelm that snared us. The streets stretched out before us in great slabs of polished white and grey stone. We didn’t know where to start, so we headed in the direction of the biggest monument near the entrance – the theatre.

The theatre of Thugga is incredibly intact, and as we climbed the concentric rows of seating to the top, the picture of Thugga became much more clear as it spread out before us.

The Capitol of Thugga – the Temple of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva

From the top row of the theatre I could see the high part of the town with the capitolium and agora beside it, the market place, the curve of one of the main streets passing the baths and going farther down into the residential part of ancient Thugga.

Five thousand residents may not seem like many, but when you look at a sprawling site like this, so quiet and complex, you begin to hear the voices of the past in a way that makes visiting an isolated archaeological site a truly unique experience.

To me, Thugga is a place of ghosts.

At every turn, I felt like I was intruding upon someone – a priest sacrificing in the Temple of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, a slave buying supplies in the marketplace, a couple of locals discussing business in the agora, or two ladies whispering in hushed tones in the baths where they stand upon the black and white geometric mosaic floor that was open to the sky. From the marble-framed doorway of a private domus, a mother watches me pass while her child plays on the stoop at her feet… It was the same, everywhere we went.

Inside one of the public baths, mosaics open to the sky!

As we walked around, the voices Thugga’s residents became louder in my ears, their shades passing around me as they went about their daily business.

I was blown away by the fact that this almost completely intact city was just sitting there, deserted, its mosaics open to the sky.

Even more shocking was that as I walked around, the seeds of my story began to take shape in my mind. I saw Lucius walking through these very streets, visiting the temple, the marketplace, being pursued by local thugs.

What I didn’t see was the young prostitute who would approach him on that very street I was walking on, and how she would be the only person who could help him in a time of need.

Seeing my characters wander down this main street…

As a writer, it’s a magnificent experience to have your story take shape like that. I didn’t realize it fully at the time as I stepped into the ruins of the brothel, or the public latrine, following the road down toward the second century B.C. Libyan-Punic mausoleum to look out over the valley.

As I stood there, our short, almost cruel, hour hard upon us, I can’t recall hearing any birdsong, tractors in neighbouring fields, or distant cars.

What sticks with me from my time in Thugga, apart from the wondrous physical remains, is the sound of the wind and the ghostly whispers of its citizens in my ears.

It really is one of the most amazing places I have ever travelled to, and the fact that it was deserted was a gift.

View of the lower town from the baths