It’s the end of October, and as it is the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain I thought it would be a good idea to look a place that is both mysterious and iconic: Glastonbury Tor.

To most, the mere mention of Glastonbury will likely conjure images of wild, scantily clad or naked youths and aged hippies. You’ll think of thousands of people covered in mud as they wend their way, higher than the Hindu Kush, among the tent rows to see their favourite artists rock the Pyramid Stage.

It’s a great party, but to me that’s not the real Glastonbury.

This small town in southwest Britain is an ancient place. The real Glastonbury is a place of mystery, lore and legend. It is a place that was sacred to the Celts, pagan and Christian alike, Saxons, and Normans. For many it is the heart of Arthurian tradition, and for some it is the resting place of the Holy Grail.

Today, Glastonbury is a place where those seeking spiritual enlightenment are drawn. The New Age movement is going strong there, yet another layer of belief to cloak the place.

I lived in the countryside outside of the town for about 3 years and I never tired of walking around Glastonbury and exploring the many sites that make it truly unique.

From where I lived on the other side of the peat moors, I awoke every morning to see Glastonbury’s majestic Tor shrouded in mist.

My morning view of the Tor across the Somerset levels

Tor is a word of Celtic origin referring to ‘belly’ in Welsh or a ‘bulging hill’ in Gaelic. Glastonbury Tor thrusts up from the Somerset levels like a beacon for miles around. Every angle is interesting. On the top is the tower of what was the church of St. Michael, a remnant of the 14th century. Before that, there was a monastery that dated to about the 9th century A.D.

However, habitation of this place goes much farther back in time with some evidence for people in the area around 3000 B.C. But it was not always a religious centre. In the Dark Ages, the Tor served a more militaristic purpose and there are remains from this period.

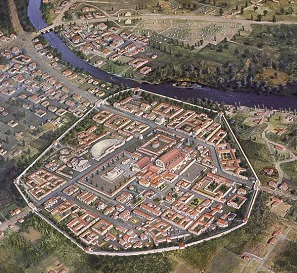

In Arthurian lore, the Isle of Avalon is a sort of mist-shrouded world that is surrounded by water and can only be reached by boat or secret path. In fact, during the Dark Ages and into later centuries, until the drainage dykes were built, the Somerset levels were prone to flooding. This flooding made Glastonbury Tor and the smaller hills around it true islands. With the early morning mist that covers the levels, this watery land would have been a relatively safe refuge for the Druids, and early Christians, Dark Age warlords and late medieval monks.

The Tor surrounded by flooded levels – Avalon!

In Celtic myth, Glastonbury Tor is said to be the home of Gwynn ap Nudd, the Faery King and Lord of Annwn, the Celtic otherworld.

Gwynn ap Nudd is the Guardian of the Gates of Annwn. He is an Underworld god. It is at Samhain that the gates of Annwn open. This was also the place where the soul of a Celt awaited rebirth. (Quick hint: We delve into this in the upcoming Eagles and Dragons novel, Warriors of Epona!)

If you are on the Tor at Samhain, you may hear the sound of hounds and hunting horns as the lord of Annwn emerges for the Wild Hunt of legend.

The Wild Hunt 1872 by Peter Nicolai Arbo

In Arthurian romance, there is a tradition of the wicked Melwas imprisoning Guinevere on the Tor. Arthur rides to the rescue, attacks Melwas and saves Guinevere. This particular story mirrors an episode in Culhwch ac Olwen, one part of the Welsh Mabinogion, in which Gwythyr ap Greidawl attempts to save Creiddylad, daughter of Lludd, whom he is supposed to marry, from Gwynn ap Nudd himself.

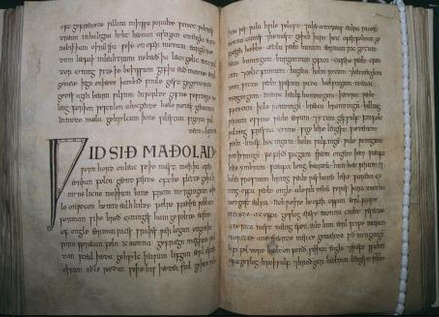

Another even more fascinating Arthurian connection can be found in a pre-Christian version of the ‘Quest of the Holy Grail’, called the ‘Spoils of Annwn’ which was found in the ‘Book of Taliesin’. In this tale, Arthur and his companions enter Annwn to bring back a magical cauldron of plenty. In this, some say that ‘Corbenic Castle’ (the ‘Grail Castle’) is actually Glastonbury Tor. It isn’t just Herakles and Odysseus who journeyed to the Underworld!

Glastonbury Tor is not only associated with Celtic religion, myth and legend. It is also said by some to be a place of power or a sort of vortex in the land that lies along some of the key ley-lines, including what is called the St. Michael ley-line. The majority of sites associated with St. Michael, the slayer of Satan, along the ley-line were indeed places of power and belief of the old religion.

But this is nothing new. Christians built on top of sites sacred to the pagans they were eager to overcome. What better way to symbolize your ‘victory’ than to build right on top of a site and make it yours.

‘Gates of Annwn and Gwynn ap Nudd? Let’s build a church of St. Michael on top of it! That’ll show ‘em!’

Artist impression of Gwynn ap Nudd at the hunt

But myth and legend persist through story and place, and the Tor is a prime example of how successive traditions do not overcome each other, but rather combine to make up the various aspects of that place.

If you ever get to Glastonbury, the Tor is a definite must. Walk to the top and sit awhile. Look out over the landscape and watch the crows and magpies dive in the wind around the steep slopes. Close your eyes and listen. While you’re there, you can decide whether you are sitting on a natural formation, a ceremonial labyrinth, a hill fort, a sleeping dragon, the mound where Arthur sleeps until he is needed once more, or the doorstep of the Gates of Annwn itself! The Tor is all of these things and more.

However, no matter what you believe, one thing is certain: Glastonbury Tor remains a site of extreme beauty and mystery that is well worth a visit, even if it is just to watch the sun sink in the West.

Have a safe and happy Samhain.