One of the things that fascinates me the most about studying the ancient world is the vast array of gods and goddesses. They all played an important role in the day-to-day lives of ancient Greeks, Romans, Celts and others.

There were many deities associated with agriculture in ancient Rome, Ceres and Saturn, for example. Many gods and goddesses, major and minor, could affect crops, agricultural endeavours and the subsequent harvests.

When you hear the name of Mars, agriculture is not the first thing that comes to mind. When I think of the Roman god, Mars, I think of one thing.

WAR.

The Roman God of War was second to none other than Jupiter himself in the Roman Pantheon.

The Romans were a warlike people after all, and so Mars always figured prominently.

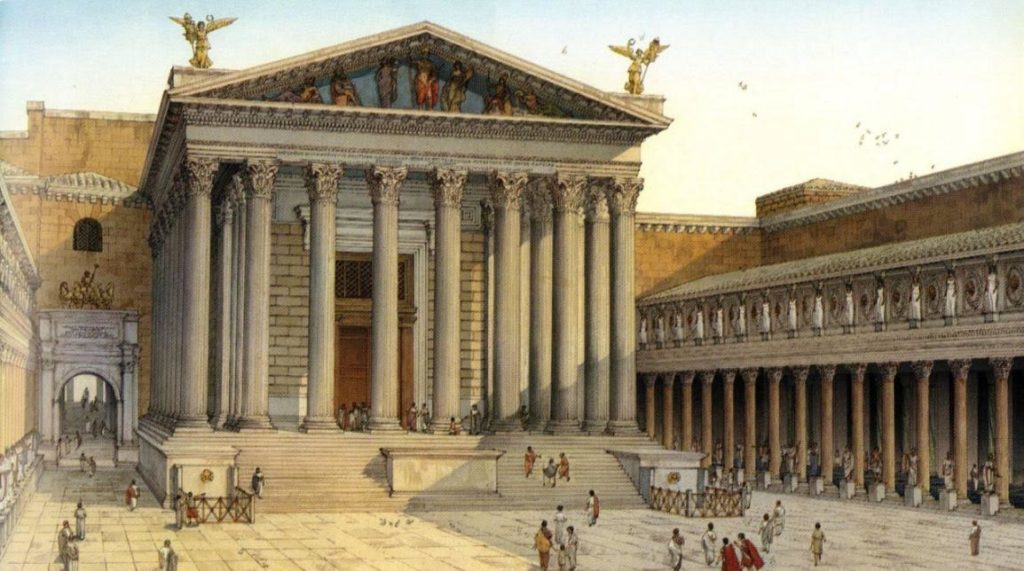

Octavian (later the Emperor Augustus) vowed to build a temple to Mars in 42 B.C. during the battle of Philippi in which he, Mark Antony and Lepidus finally defeated the murderers of Julius Caesar. When Augustus built his forum in 20 B.C. the Temple of Mars Ultor (the Avenger) was the centrepiece.

“On my own ground I built the temple of Mars Ultor and the Augustan Forum from the spoils of war.” (Res Gestae Divi Augusti)

Artist impression of temple of Mars Ultor (the ‘Avenger’)

People often think that Mars was the Roman name given to Ares, the Greek God of War, as was the case with many other gods in Roman religion. This is not exactly true.

In the Greek Pantheon, Ares was simply God of War, brutal, dangerous and unforgiving. To give oneself over to Ares was to give in to savagery and the animalistic side of war. Fear and Terror were his companions. Most Greeks preferred Athena as Goddess of War, Strategy and Wisdom.

Mars was a very different god from Ares. He was a uniquely Roman god. He was the father of the Roman people.

Mars was the God of War, true, but he was also a god of agriculture.

Just as he protected the Roman people in battle, so too did Mars guard their crops, their flocks, and their lands.

War and agriculture were closely linked in the Roman Republic. Most Romans who fought in the early legions were farmers who had set aside their plows and scythes to pick up their gladii and scuta when called upon to defend their lands. One of the most cited examples of this is Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (519 BC – 430 BC), one of the early Patrician heroes of Rome.

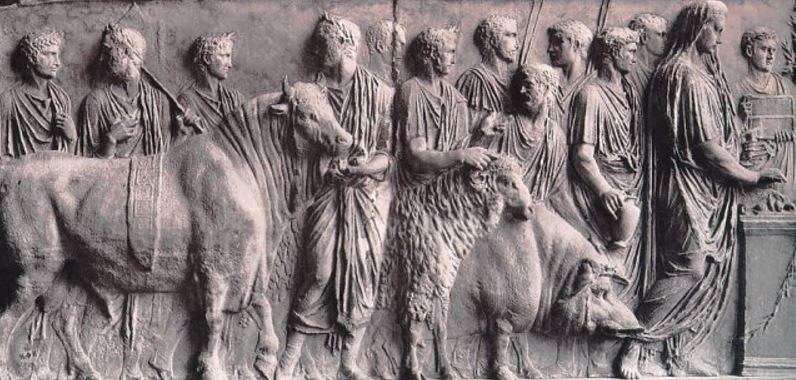

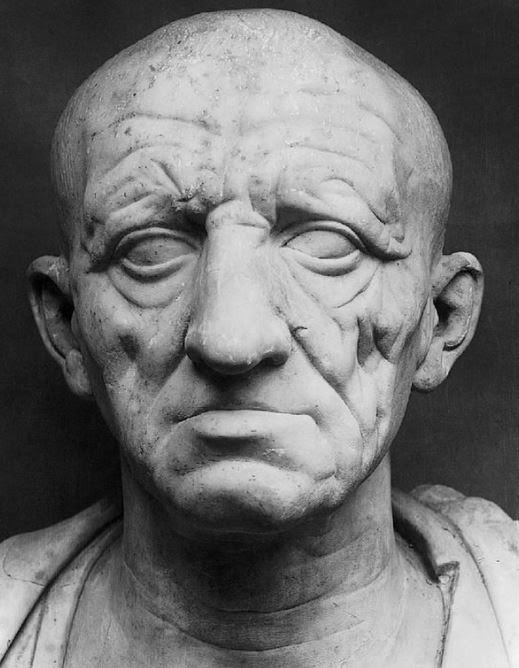

In his work De Agri Cultura, Marcus Porcius Cato (234 BC– 149 BC) speaks at length about the tradition of the suovetaurilia, a sacrifice that was made roughly every five years and occasionally at other times. This ceremony was a form of purification, a lustratio.

Relief of a Suovetaurilia ceremony

The highly sacred suovetaurilia was dedicated to Mars with the intent of blessing and purifying lands.

It involved the sacrifice of a pig, a sheep, and a bull – all to Mars.

The sacrifice was done after the animals were led around the land while asking the god to purify the farm and land.

Cato describes the prayer that is uttered to Mars once the sacrifices have been made:

“Father Mars, I pray and beseech thee that thou be gracious and merciful to me, my house, and my household; to which intent I have bidden this suovetaurilia to be led around my land, my ground, my farm; that thou keep away, ward off, and remove sickness, seen and unseen, barrenness and destruction, ruin and unseasonable influence; and that thou permit my harvests, my grain, my vineyards, and my plantations to flourish and to come to good issue, preserve in health my shepherds and my flocks, and give good health and strength to me, my house, and my household. To this intent, to the intent of purifying my farm, my land, my ground, and of making an expiation, as I have said, deign to accept the offering of these suckling victims; Father Mars…“

(Cato the Elder; De Agri Cultura)

Cato the Elder

This is not a prayer to the bloodthirsty god of war that Ares was.

The words and actions above evoke a wish from a child to a supreme father and protector. We see the fears that would have occupied the minds of the Roman people. No matter how mighty in war they may have been, if crops failed and disease spread, they would have been lost.

Romans prayed to Ceres and Saturn for the success of their crops, for abundance.

But the prayer above was to Mars, he who held Rome’s enemies, the enemies of its lands, at bay.

In war and in peace, Mars was always the guardian of his people.

Thank you for reading

If you want a clearer understanding of the suovetaurilia ceremony, and the meaning of this interesting Latin compound word, here is a very short presentation: https://youtu.be/pz1KiILdW2s

Hello Adam

Great post about Mars. Knowing his other position as a god of agriculture offers a variant perspective on the Founding of Rome as well, at least for me. After all, Romulus’ original followers were mostly shepherds, herdsmen and possibly pastoralists as well! Not soldiers or formal warriors.

Glad you liked the post, Marie. It does give a different perspective on the founding of Rome. On that, I’ve been reading Mary Beard’s book, SPQR, and she talk a lot about the founding of Rome and the stories of Romulus. Seems Rome was also founded by criminals and refugees as well – people who were not accepted elsewhere but brought into the fold by Romulus. Interesting theory anyway. Cheers and thanks for your comment!

I particularly like the last picture in this interesting article – the Italian countryside as it might look in any age. Wish I was there!

Cheers Lin! Yes, Tuscany is one of my favourite places in the world. I often wish I was back there too!

Thank you for a very good article.

Cheers, Bert! I’m glad you liked this article. Many thanks for your comment!

A great post, very interesting how Mars and Ares are so different.

Cheers, Lucy! Glad you liked the post. I agree. I think a lot of people don’t realize that the two gods of war are quite different in some ways. Thanks for your comment