Salvete Readers and History-lovers!

Happy New Year to all of you, and may this new decade bring you much love, joy, good health, and prosperity in all you do!

I’ve been off for a couple of weeks after a full autumn of blogging, right up to threshold of 2020, but now it’s time to get back down to work and bring you all more history and historical fiction!

I thought it would be nice to start the year off right with a new Ancient Everyday post about one of the most important gods in ancient Rome: Janus.

Janus, the two-faced god. Give him a thought as we step from one year into another.

See Janus comes…the herald of a lucky year to thee, and in my song takes precedence. Two-headed Janus, opener of the softly gliding year, thou who alone of the celestials dost behold thy back, O come propitious to the chiefs whose toil ensures peace to the fruitful earth, peace to the sea. And come propitious to thy senators and to the people of Quirinus, and by thy nod unbar the temples white. A happy morning dawns. Fair speech, fair thoughts I crave! Now must good words be spoken on a good day.

(Ovid, Fasti, Book I, Kalends, Ianuarius)

Unlike many other gods, there was no equivalent to Janus in Greek myth. He was a uniquely Roman god.

In Roman mythology, Janus was said to be the first king of Latium. He pursued caught up with the virgin nymph, Carna (who usually escaped her suitors), and in return he gave her power over door hinges and a branch of hawthorn to keep evil spirits away from thresholds and doorways.

Janus was also the father of Tiberinus, who gave his name to the River Tiber, and of the nymph Canens, by Venilia, who married Picus, the son of Saturn, both of whom were tortured by the jealous enchantress, Circe.

While the fates guard Canens, Janus’s daughter, for me [Picus], I will not harm our bond of affection by an alien love. Repeating her entreaties, time and again, in vain, Circe cried: ‘You will not go unpunished, or return to your Canens, and you will learn the truth of what the wounded; a lover; a woman, can do: and Circe is a lover; is wounded; is a woman!’

(Ovid, Metamorphoses, XIV:320-396)

Circe Changing Picus into a Bird (Circes concubitum detestatur Picus), from Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ (Wikimedia Commons)

The mythology around Janus is fascinating enough, but even more so are the aspects of this Roman god.

Janus is one of those gods who permeated many aspects of Roman life, but one who is sometimes glossed over when looking at ancient Rome today.

Janus was really everywhere. Right now, we find ourselves in the month of Janus, or Ianuarius, as the Romans said. That’s January to all of us. Why is the month of January named after this archaic Roman god?

Among the many aspects of Janus, he was the Roman god of new beginnings, as well as endings. Not only was January dedicated to Janus, but also the kalends (the first day) of every month were as well.

When Romans wanted to bless the beginning of anything new – a month, a year, a journey, a business venture etc. – Janus was the first god they prayed to. As the god of beginnings, Janus was always the first god to be named on any list of the gods, or honoured in any ceremony, no matter for which god the ceremony was dedicated. He was also the first god to receive a portion of the sacrifice.

But Janus was not just a god of new beginnings. There was much more to this fascinating, most-ancient god of the Roman pantheon.

Remains of the Temple of Janus in Rome (Wikimedia Commons)

Janus was also a god of gates and doorways, and this is one reason for which he is often depicted as having two faces. Janus ‘Bifrons’ guarded over transitionary places such as gates and doorways, or even the crossing point of one year to the other, his two faces simultaneously looking forward and backward, seeing all.

As the god who oversaw passageways and doorways, Janus was the god who allowed mortals to communicate with the other gods, and so his invocation at the outset of a religious ceremony was crucial.

But there are even more aspects to Janus.

Janus ‘Patulcius’ was the god who actually opened doors, and Janus ‘Clusivus’ was the god who closed doors.

Janus ‘Consivius’, was a god of change and of time who was also invoked at important events such as marriage, or death, or at harvest and planting times of year.

Janus ‘Quirinus’ was the god of the all-important Roman passage from war to peace, from soldier to citizen.

In ancient Rome, however, Janus was probably most worshiped as Janus ‘Pater’, Janus the Father who was a god of creation, or a primal creator in the form of Chaos.

Definitely a god you want to have on your side.

A print from Bernard de Montfaucon’s L’antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures with different images of Janus. (Wikimedia Commons)

The ancients called me Chaos, for a being from of old am I; observe the long, long ages of which my song shall tell. Yon lucid air and the three others bodies, fire, water, earth, were huddled all in one. When once, through the discord of its elements, the mass parted, dissolved, and went in diverse ways to seek new homes, flame sought the height, air filled the nearer space, while earth and sea sank in the middle deep. ‘Twas then that I, till that time a mere ball, a shapeless lump, assumed the face and members of a god. And even now, small index of my erst chaotic state, my front and back look just the same. Now hear the other reason for the shape you ask about, that you may know it and my office too. Whate’er you see anywhere – sky, sea, clouds, earth – all things are closed and opened by my hand. The guardianship of this vast universe is in my hands alone, and none but me may rule the wheeling pole. When I choose to send forth peace from tranquil halls, she freely walks the ways unhindered. But with blood and slaughter the whole world would welter, did not the bars unbending hold the barricadoed wars. I sit at heaven’s gate with the gentle Hours; my office regulates the goings and the comings of Jupiter himself. Hence Janus is my name; but when the priest offers me a barley cake and spelt mingled with salt, you would laugh to hear the names he gives me, for on his sacrificial lips I’m now Patulcius and now Clusius called. Thus rude antiquity made shift to work my changing functions with the change of name. My business I have told. Now learn the reason for my shape, though already you perceive it in part. Every door has two fronts, this way and that, whereof one faces the people and the other the house-god; and just as your human porter, seated at the threshold of the house-door, sees who goes out and in, so I, the porter of the heavenly court, behold at once both East and West.

(Ovid, Fasti, Book I, Kalends, Ianuarius)

Janus was honoured at many different times of year, and for various events, but his main festival was, oddly enough, held on the 17th of August. This was also the festival of Portunus, or Portunalia, which honoured the god who protected doors and harbours.

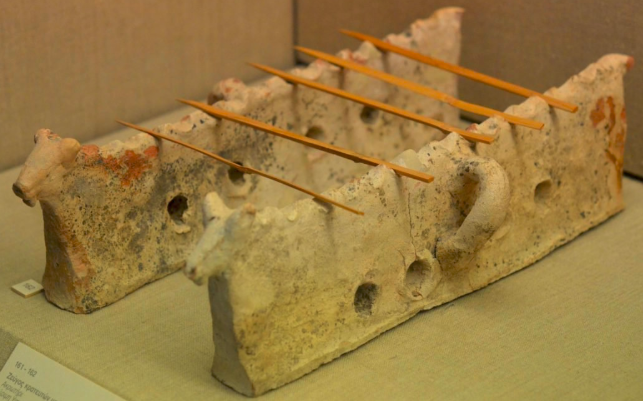

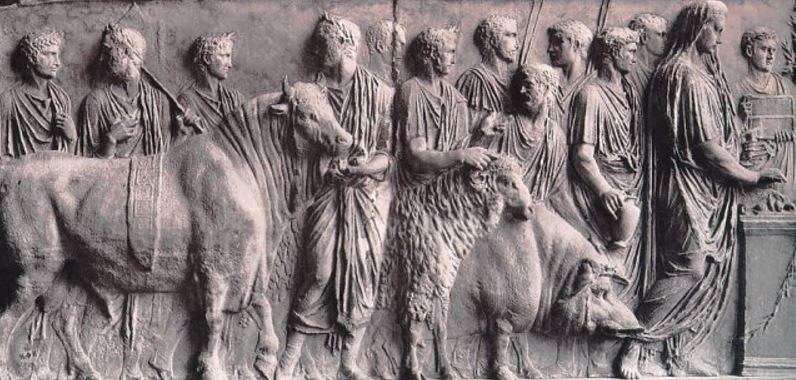

Rites dedicated to Janus at these various times of year, including the start and end of the military campaigning season (March and October) included offerings of spelt cakes and salt that were burned upon altars.

And on New Year’s Day – a very important beginning up to our own day – people gave gifts of dates, figs, honey, salt and coins.

One important tradition we still honour today is the offering of good wishes and cheerful words at New Year. All of these honoured Janus!

Interestingly, Janus did not have a specific priest in ancient Rome. The rites for him were performed by the Rex Sacrorum, the ‘King of the Sacred Rites’.

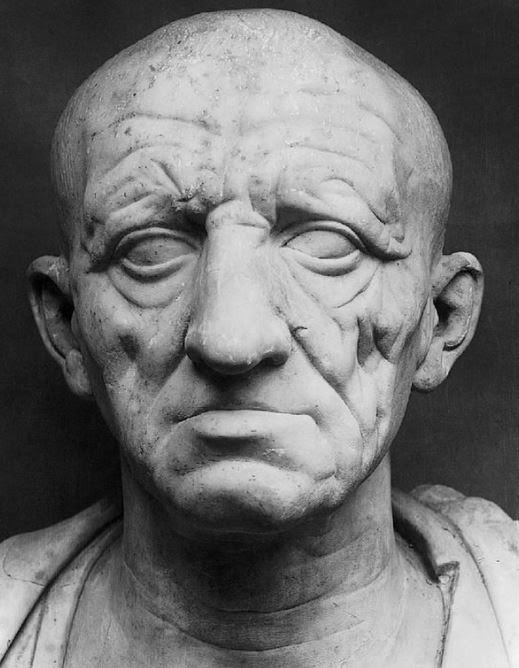

Janus had various shrines dedicated to him in Rome, but perhaps the most famous was the one built by King Numa Pompilius (c. 715-673 B.C.) the second king of Rome, after Romulus himself. Religion was important to King Numa.

The temple of Janus was built by Numa in the Forum Romanum, but this was no ordinary temple. It was more of an East-West passageway with doors at each end.

This temple represented the beginning and end of war or conflict, and the journey that entailed. During war, the doors of the temple of Janus were left open, but during peace time, the doors were closed.

Needless to say, in ancient Rome, as the Empire expanded, the doors were more often open than closed.

He [Janus] also has a temple at Rome with double doors, which they call the gates of war; for the temple always stands open in time of war, but is closed when peace has come. The latter was a difficult matter, and it rarely happened, since the realm was always engaged in some war, as its increasing size brought it into collision with the barbarous nations which encompassed it round about. But in the time of Augustus Caesar it was closed, after he had overthrown Antony; and before that, when Marcus Atilius and Titus Manlius were consuls, it was closed a short time; then war broke out again at once, and it was opened. During the reign of Numa, however, it was not seen open for a single day, but remained shut for the space of forty-three years together, so complete and universal was the cessation of war. For not only was the Roman people softened and charmed by the righteousness and mildness of their king, but also the cities round about, as if some cooling breeze or salubrious wind were wafted upon them from Rome, began to experience a change of temper, and all of them were filled with a longing desire to have good government, to be at peace, to till the earth, to rear their childrenin quiet, and to worship the gods.

(Plutarch, The Life of King Numa, XX)

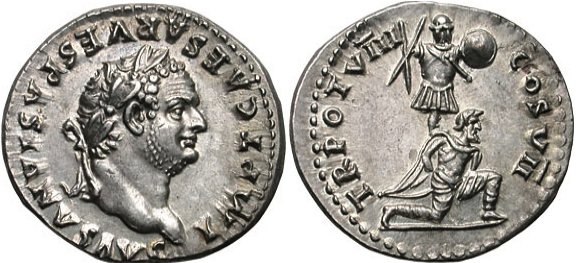

Temple of Janus on a coin minted by Nero (54-68 A.D.) Note that the doors are closed.