It has to be admitted that learning does take something away – as a file takes something from a rough surface, or a whetstone from a blunt edge, or age from wine – but it takes away faults, and the work that has been polished by literary skills is diminished only in so far as it is improved… (Marcus Fabius Quintilianus)

Salvete, Romanophiles!

I think that most of us will agree that education is crucial to our quality of life and, if we are to take the Roman educator Quintilian’s word for it, learning only makes things better.

Education, however, is perhaps something that we take for granted in the West where most children have free access to a primary and secondary school education, and some beyond that. Today, education up to some level, is assumed.

But was it the same in ancient Rome?

In this new Ancient Everyday post, we’re going to take a very brief look at education in ancient Rome from the early Republican age on into the imperial period.

If you missed the previous two-part Ancient Everyday post on food and dining in ancient Rome, you can check that out by clicking HERE.

When I think of education in the ancient world, I have to admit that my first thoughts are of ancient Greece and the golden age of Athens which, let’s face it, created the foundations of education in the western world, especially a liberal arts education.

But even in ancient Greece, there were other systems. The Spartan agoge springs to mind, that educational machine of war that took young boys at 7 years of age and thrust them into a world of brutality and torture to create the best warriors of the ancient world.

When it comes to the Romans, however, education was more practical, a happier medium between philosophical discourses of Athens and the trials of Sparta’s agoge.

Throughout most of the Rome’s Republican age, homeschooling was how young boys, and sometimes girls, were educated. They were taught by members of their family, either the father and/or mother, or some other relative who may have been more qualified.

Boys were most often educated by their fathers in Republican Rome. The paterfamilias controlled everything, and made all the decisions about his children’s education, even whether or not they received one at all.

For another post on the role of the paterfamilias in Roman society, click HERE.

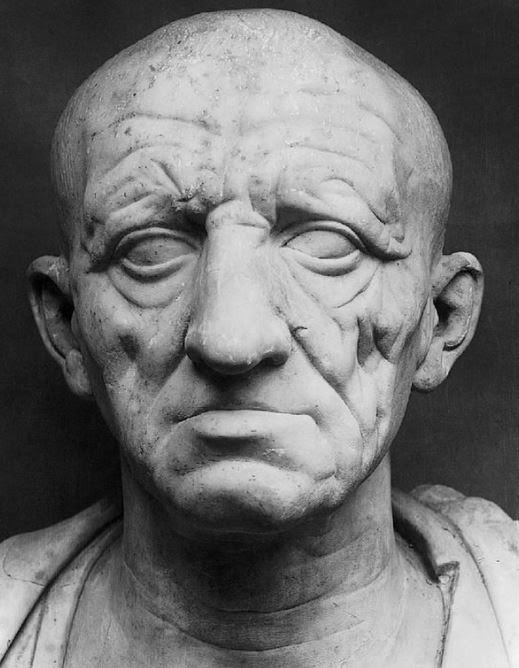

Cato thought it not right, as he tells us himself, that his son should be scolded by a slave, or have his ears tweaked when he was slow to learn, still less that he should be indebted to his slave for such a priceless thing as education. He was therefore himself not only the boy’s reading-teacher, but his tutor in law, and his athletic trainer, and he taught his son not merely to hurl the javelin and fight in armour and ride the horse, but also to box, to endure heat and cold, and to swim lustily through the eddies and billows of the Tiber. His History of Rome, as he tells us himself, he wrote out with his own hand and in large characters, that his son might have in his own home an aid to acquaintance with his country’s ancient traditions. (Plutarch, The Life of Cato the Elder)

From about the age of seven, Roman boys were trained by their fathers in the areas that were deemed most important to life as a Roman citizen: reading, writing, and weapons training. You can see from the quote above that Cato the Elder pursued this course with his own son.

Boys would also have accompanied their fathers on religious duties, as well as senatorial duties if they were from a senatorial family. Everything was geared toward an effective public life as a Roman citizen, and while boys were groomed for public life, girls were likewise groomed and trained in reading, writing, and arithmetic so as to be able to run an effective household.

At sixteen years of age, the boys of nobles were given a political apprenticeship, and then at seventeen, they spent the campaigning season with the army so as to learn the business of war, Rome’s bread and butter, so to speak.

This system of traditional homeschooling went on into the imperial age in some families, but it was in the third century B.C. that things changed and new ideas crept into the Roman educational system.

With the capture of the Greek colony of Tarentum in southern Italy in 272 B.C., and then the annexation of Sicily in 241 B.C., there was an influx of Greek prisoners of war and slaves into Roman society, and with them came Greek ideas.

Many of the Greeks who were brought into Roman society became teachers or private tutors.

Perhaps the most famous of this first wave of Greeks was Livius Andronicus (284-205 B.C.) who became a slave and tutor to his dominus’ children. He later was freed, and decided to stay in Rome where he is said to have become the first teacher of Greek education. He was also responsible for translating the Odyssey into Latin.

It was people like Andonicus who introduced the literary education to Rome, for prior to that, the focus in Roman education was more practical and martial.

But there remained differences between the Greek and Roman educational mindset for some time. For example, in the Greek educational system, music and athletics were of prime importance. These two areas were not taken seriously in Rome. To Greeks, music enriched the soul, but to Romans, music was perceived as a path to moral corruption.

I doubt that Cato the Elder was very musical!

Likewise, to the Greeks, the goal of athletic competition and training was to obtain a beautiful and healthy body, a noble goal in and of itself. In Rome, athletics were only seen as a way to maintain good soldiers who would fight for Rome.

Again, Romans were much more practical in their education and the goals of that education.

The study of literature, however, became more important in Rome as time went by, as it was seen to be beneficial in producing effective speakers. In a society where public life was so important, especially among the upper classes, this skill was crucial.

So, generally, what were the stages of the Roman educational system?

The first step was a sound moral education, and this began at home with fathers and mothers teaching their children (boys and girls) what Roman mores dictated were right and wrong, duties to family, to Rome, and to the gods themselves. In ancient Greece, community was central to moral education, but in Rome, it was all about family.

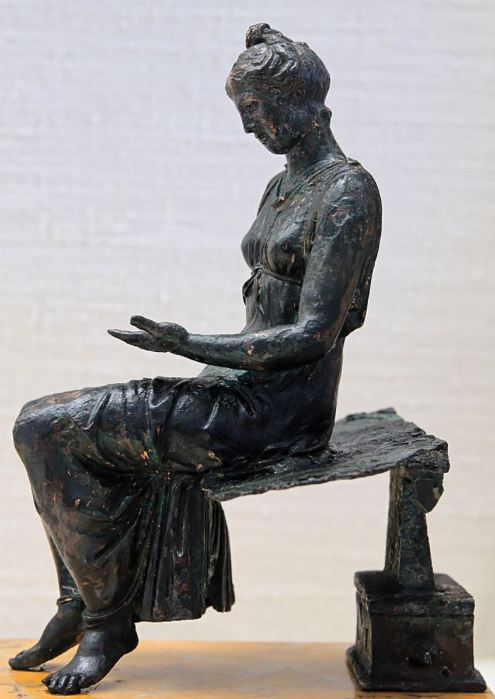

Formal early education began at age seven and lasted until age eleven. This included reading, writing and arithmetic taught by a litteratoror, in Greek, a paidagogus. Both boys and girls received this early education.

The rich tended to have private tutors for their children, but there were supposedly schools for the poor. This sort of school was known as a ludus litterarius. Because of the low wages paid to a litterator of the time, many such teachers also set up private schools of their own along the Greek tradition. These private schools did not have set locations, but rather moved around.

Secondary education in ancient Rome took place from twelve to fifteen years of age, and lessons were taught by a grammaticus.

The foci here were the literary subjects and the analysis and expression of ideas, and lessons were taught in both Greek and Latin. The purpose of the secondary education (more often of the upper classes) was for general education, but also to prepare for the all-important training in rhetoric. Many classical Greek texts were used, but as time passed and more Latin writers emerged, texts would have included the works of Ennius, Virgil and others.

Again, secondary education would have taken place in private, or in groups in various places.

The final major stage of education in ancient Rome was training in rhetoric.

Painting depicting Cicero speaking out against Cataline in the Senate – putting his rhetoric to good use!

Thank you for this very informative post Adam. Some people say what did the Romans ever do for us. I would say they gave us education along with the Greeks Great post !!

Cheers, Rita! So glad you liked this one. Yes, the Romans did so much for us! That reminds me of that wonderful series from a few years back – ‘What the Romans Did for Us’ – with Adam Hart Davis. Some of the most obvious things we take for granted today were in fact given to us by the Romans. Thanks for your comment 🙂

Adam,

As a semi-retired Teacher, Outdoor Educator, and Middle School Administer of 50 years, your post really resonated with me. My BA in Classical Philosophy, and the Liberal Arts bent of the K-12 Independent School I work at in Honolulu both flow from the roots you dsscribe. There still is much to be said for a broad education built on lasting values, understanding the past, exposure to great Art, literature, with a central emphasis on effective verbal and written communication…. supported by the old Greek guideline: “Nothing to Excess”.

It’s a pity our modern arragance sometimes condems us to repeat mistakes of the past… but that’s not really anything new.

We do owe much of this formula to the Greek and Roman Civilizations.

Thank you very much for your comment, Timothy. Even after years of study and ‘working with’ history, I’m still surprised by how much we owe our ancient ancestors. As you say, it is a shame mistakes are repeated. If more people studied history, and made an attempt to understand it, the world certainly would be a better place. The research on this post for education definitely was an eye-opener. I’m very glad you enjoyed it and that it resonated with you. Cheers!