ancient history

Another New Eagles and Dragons Series Release – The Stolen Throne is out now!

Last month, we announced the release of Isle of the Blessed, the fourth book in our #1 bestselling Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series. You can check that out by CLICKING HERE.

This month, we’re thrilled to announce the release of Book V of the Eagles and Dragons series: The Stolen Throne.

Here is the cover and synopsis of this exciting new addition to the Eagles and Dragons series:

At the peak of Rome’s might, a dragon is born among eagles, an heir to a line both blessed and cursed by the Gods for ages.

What happened to Lucius Metellus Anguis in the wilds of Dumnonia?

The Gods have finally granted Lucius and his family what appears to be a peaceful life in a new home surrounded by friends. The memories of pain and war are finally beginning to diminish.

But when Einion, Lucius’ friend and ally, sets out to reclaim his homeland from the man who murdered his family, Lucius knows he must help. Their quest takes them on a deadly journey beyond the reach of Rome, deep into Dumnonia, a mysterious and troubled land that has been ravaged by its false king.

As Lucius and his friends journey across the ancient moors, they rally support from unexpected allies. A plan is devised and the attack is set for the night of Samhain. They must all fight or die for the stolen throne of Dumnonia.

However, all is not as it seems. Lucius’ enemies emerge from the shadows, determined to isolate and slay the Dragon of Rome once and for all.

Does Einion finally reclaim his father’s stolen throne? What happens to Lucius upon the quest that changes him forever?

Step into a world beyond the veil as Lucius faces a deadly enemy and learns a truth that shakes the foundations of the world he knows and believes in.

This story will take you to a place beyond the reach of Rome’s Empire, a place full of mystery and emotion where all is not as it seems, a place from which few heroes return.

You haven’t read anything like this before!

You can learn more about The Stolen Throne (Eagles and Dragons – Book V) and find all the links to get your copy right here:

https://eaglesanddragonspublishing.com/books/the-stolen-throne-eagles-and-dragons-book-v/

The Stolen Throne is available in e-book format at all major on-line retailers, and currently in paperback from Amazon.

If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series, you can start the series for FREE with the full-length novel, The Dragon: Genesis, which you can download by CLICKING HERE.

Here’s to a new adventure in the Roman Empire!

Happy Reading!

A New Eagles and Dragons Series Novel!

We’re excited to announce the official launch of Isle of the Blessed, Book IV in the #1 bestselling Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series.

Fans of this series have been waiting quite a long time for this book, but now the wait is over.

Sound the cornu and slam your gladii against your scuta!

Isle of the Blessed – Eagles and Dragons Book IV

At the peak of Rome’s might, a dragon is born among eagles, an heir to a line both blessed and cursed by the Gods for ages.

Emperor Septimius Severus’ war against the Caledonians has ended with a peace treaty. Rome has won.

As a reward for the blood they have shed, many of Rome’s warriors have been granted a reprieve from duty, including Lucius Metellus Anguis, prefect of the now famous Sarmatian cavalry.

The Gods seem finally to have granted Lucius a peaceful life as he builds a new home for his family upon an ancient hillfort in the south of Britannia. Lucius now finds that, after years of war and brutality, the most elusive peace, the peace within, is finally within his grasp.

But heroes are never without enemies, and Lucius, Rome’s famed Dragon, has many.

After an argument with traitorous local politicians, and a quest in which he is confronted by a dark goddess, Lucius realizes that his pastoral idyll is at an end. When war erupts in Caledonia once more, he is called away only to be assaulted on all fronts by his most deadly enemy.

The choices presented to Lucius by the Gods, his allies, and his friends are clear and terrifying. He can hand victory and power over to the wickedest men in the Empire, or he can fight for his life to create the world he believes in.

Will Lucius’ enemies and the powers of darkness overwhelm and destroy him? Or will he find the strength to survive the trials he faces and protect the people he loves?

This time, not even the Gods know…

We hope you like the sound of this one. It promises to take you on an adventure in the Roman Empire that you won’t forget, and the editorial team and beta readers have told us that this is Adam’s best book to date!

You can learn more and find all the links to get your copy ON THIS WEB PAGE.

Isle of the Blessed is available in e-book format at all major on-line retailers, and currently in paperback from Amazon.

If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series, you can start the series for FREE with the full-length novel, The Dragon: Genesis, which you can download by CLICKING HERE.

Here’s to a new adventure in the Roman Empire!

Happy Reading!

Agora – A Visit to the Heart of Ancient Athens

Greetings readers and history-lovers!

It’s been a brilliant summer, but after some time off, new adventures, and a lot more writing, we’re back on with the blog.

It’s going to be a busy fall this year with some very exciting announcements coming up soon, so if you are not a mailing list subscriber, you should sign-up now so you don’t miss anything.

If you were following along on the Instagram feed, you’ll know that I was in Greece visiting with family for about five scorching weeks.

Normally, when we go back to Greece, we visit many archaeological sites, but this time, it was more about family and refilling the creative well. Besides, the days were so hot that it was bordering on dangerous. I can still feel the burning, crisping sensation on my arms!

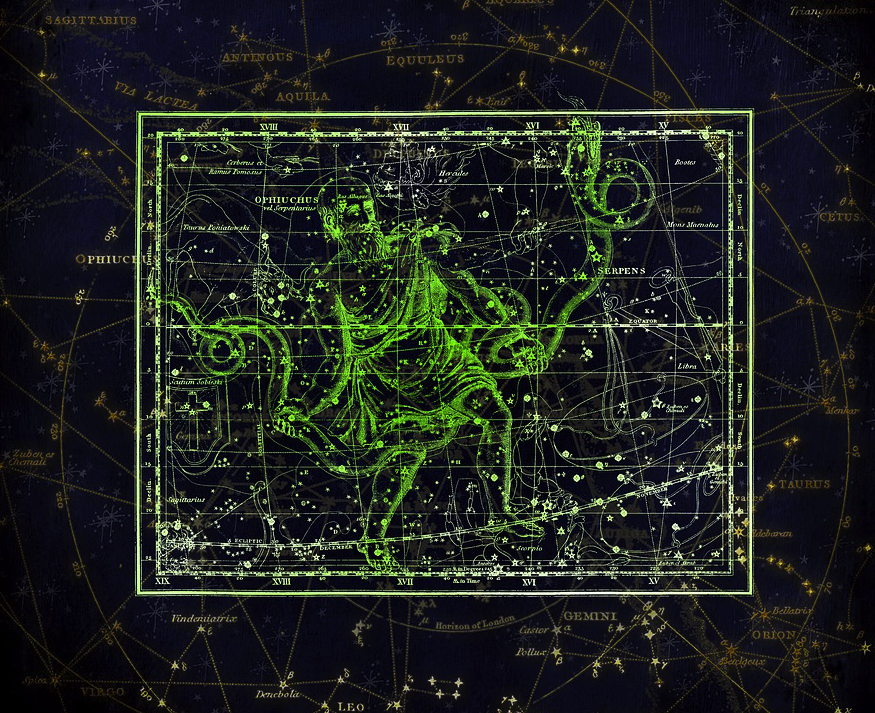

It was wonderful to hear and see that symphony of Greek summer – the gentle lap of water on pebbled beaches, brilliant sunrises that roused the chorus of cicadas, wine-filled sunsets watching the chariot of the sun disappear into the West, and night skies filled with legendary constellations – every day it was different and awe-inspiring.

I especially enjoyed the sweet scent of pine and wild thyme in the heat of day as I stared out the sky and sea, a world in myriad shades of blue…

But the historian in me would think it blasphemous to be in Greece and not visit at least one archaeological site. And so, after my seaside idyll in the Argolid peninsula, during my last couple of days in Athens, I made my way to the heart of the city to a site I had not visited in some years – the ancient agora of Athens.

Before I tell you what it felt like to return to this ancient place, here is a bit of history for those of you who are not familiar with it.

The agora has been the beating heart of ancient Athens since at least the sixth century B.C. I don’t mean human activity, for that goes march farther back. I mean that the agora has been the social, commercial, entertainment, political and religious heart of Athens since then.

Almost everything of import in Athens’ history happened in and around the agora, including the birth of Democracy.

The area of the agora is actually known as ‘Thiseio’. Years ago, when I first visited the agora, I asked about this and discovered that this stems from the mistaken belief that the intact temple of Hephaestus overlooking the site was a temple dedicated to Theseus, the legendary king of Athens (yes, Theseus who escaped the labyrinth!).

As part of the Theseus connection, there is a legend (mentioned by Pausanias) that a great battle took place on the site of the agora between the Greeks and invading Amazons who had been angered that Antiope, the sister of Queen Hippolyta and Penthesilea, fell in love with the Athenian king and returned there with him.

Antiope was killed during the battle, but Theseus and the Greeks were victorious nonetheless. As an aside, this tragic tale is depicted in a brilliant novel by Steven Pressfield, Last of the Amazons.

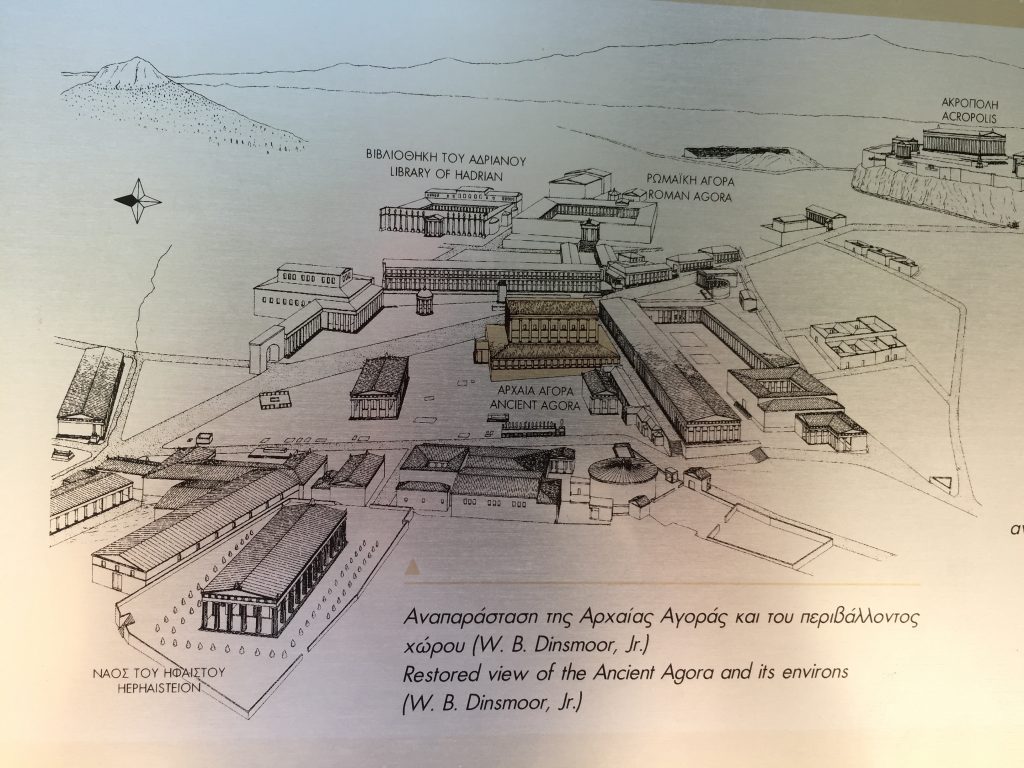

The ancient agora lies in the shadow of the Acropolis of Athens with the Areopagus (Ares’ Rock), Athens’ oldest court, to the southwest. Fun Fact: the Areopagus is called that because that is where the Gods tried Ares for murder. Murder trials continued to take place there during Athens’ history.

The agora is also flanked by the hill of Kolonos Agoraios, dominated by the temple of Hephaestus to the west, and the reconstructed stoa of Attalos to the east.

The Panathenaic Way, the road that ran from the great Dipylon Gate of Athens to the Acropolis, ran directly through the agora, as did the road to the ancient port of Piraeus.

The archaeological site is packed with ruins. In fact, excavations under the Archaeological Society and the American School of Classical Studies have been ongoing here since 1931.

The ancient agora of Athens is a place of many layers, and it’s no wonder, for it was destroyed several times in its history. The Persians destroyed it during their invasion of 480 B.C., and the Romans under Sulla did their dirty work in 86 B.C.

Later, in A.D. 267, the Herulians (a Scythian people from around the Black Sea) sacked Athens, and then the Slavs did the same in A.D. 580, not to mention the damage that was done during the wars of independence and other conflicts.

The stones of the ancient agora had born witness to a lot before being buried beneath the modern neighbourhood of ‘Vrysaki’.

I’m not going to go into every single monument that is visible today in the agora. There arsenal of ancient Athens, various stoas, the altar of Zeus Agoraios, the altar of the twelve gods, the temple of Ares, the Odeion of Agrippa, the library, and the temple of Apollo Patroos are just a few of the ruins you can wander around.

Click here for a 360 view of the Agora

Like many archaeological sites in Greece for me, a visit to the ancient agora of Athens is something more to be felt.

After taking the subway to Monastiraki station in the heart of the flea market and Plaka tourist district, we made our way through the thick and sweaty crowds, along tavernas with misting fans to the entrance on the northern side of the agora.

It seems all the world still comes to the agora of Athens. I counted about nine different languages alone in the line to get in. After a few minutes, we had our tickets and walked through to a spot away from the milling masses of snap-happy tour groups to look up and see the shining beacon of the Acropolis and the creamy white structures of the Erechtheum, Propylaea, and the Parthenon. It always fills me with silent awe to look up at that view, and the Agora is one of the best places to admire it.

To the far left, the Stoa of Attalos, where the museum is located, beckoned with its long shaded colonnades of cool marble, but we would leave that until last. Glancing up to my right, the sentry temple of Hephaestus upon the hill called to me, and so I began to make my way.

Thankfully, trees abound in the agora, so you can take your time and admire all there is to see from frequent pockets of shade brimming with cicada song.

I passed the site of the altar of the twelve gods and the overgrown ruins of the temple of Ares, unnoticed by most tourists, to stand before the imposing ruins of the Roman-build Odeion of Agrippa built in 15 B.C., and destroyed during the later Herulian attack. This spot is at the centre of the agora, and I stood there for a few minutes, gazing out from beneath the imposing statues of Tritons.

After a time pretending the murmur of tourists was the sound of ancient Athenians, I continued my walk to the altar of Zeus Agoraios, one of my favourite spots in the agora. How many offerings had been made there to the King of the Gods? The altar’s base is quite intact, and it stands in stony silence with the expanse of the agora before it, and the temple of Hephaestus and the ancient arsenal on the hill behind.

After watching most tourist by-pass Zeus’ altar as if it were just another pile of rocks, I turned around and looked up at the temple of Hephaestus, one of the most intact ancient temples I have ever seen.

The climb up is not long, but in that heat, I passed pockets of visitors resting in the shade of trees on their way up.

I couldn’t wait, however, and pressed on along the narrow, rocky path to the top.

There is something about the design of an ancient temple that appeals to my senses. I don’t know what it is. Perhaps is it is the simple lines that give one a sense of peace and order, or the ancient belief that it was where one communed with that particular god? Maybe there is something to the golden mean that permeates every aspect of those ancient structures?

I don’t know for certain, but when I am in the presence of such a beautiful structure, I fall silent. The fact that that temple is so intact makes it even more powerful.

I strolled around the perimeter of the temple, admiring the strength of its doric columns. When I reached the back, I stood peering inside, catching a glimpse of the ancient cella at its heart, so dark and quiet, cool in the middle of the inferno outside.

I had been to visit the temple before, years ago, but every time is like a first time in places like that. Our experiences change us between visits over the years. We notice new things, feel differently when we return, even though the sites themselves are frozen in time.

After admiring the temple, it was time to make our way back across the southern end of the agora toward the reconstructed stoa of Attalos. This route takes you back through the heart of the agora, along the length of the ruins of the middle stoa where you can see the rooms from which the ancient city was administered.

If you look up, you can see the Acropolis with even greater clarity, and the masses of tourists wending their way up like a flow of busy ants around a hill.

As I walked, there was much more to see, but the heat was intensifying. Some things would have to wait until the next visit.

The stoa of Attalos, built in the second century B.C. by that King of Pergamon (159-138 B.C.), was busy with people taking refuge from the shade, talking, resting, shopping in the museum shop, and admiring the remnants of Athens’ great past. You could hear tour guides teaching their groups about this history of Athens, Greek visitors talking politics, and others taking in the view and discussing the next part of their journey in Greece. The scene, apart from the clothing and languages spoken, might not have been that different from two thousand years before.

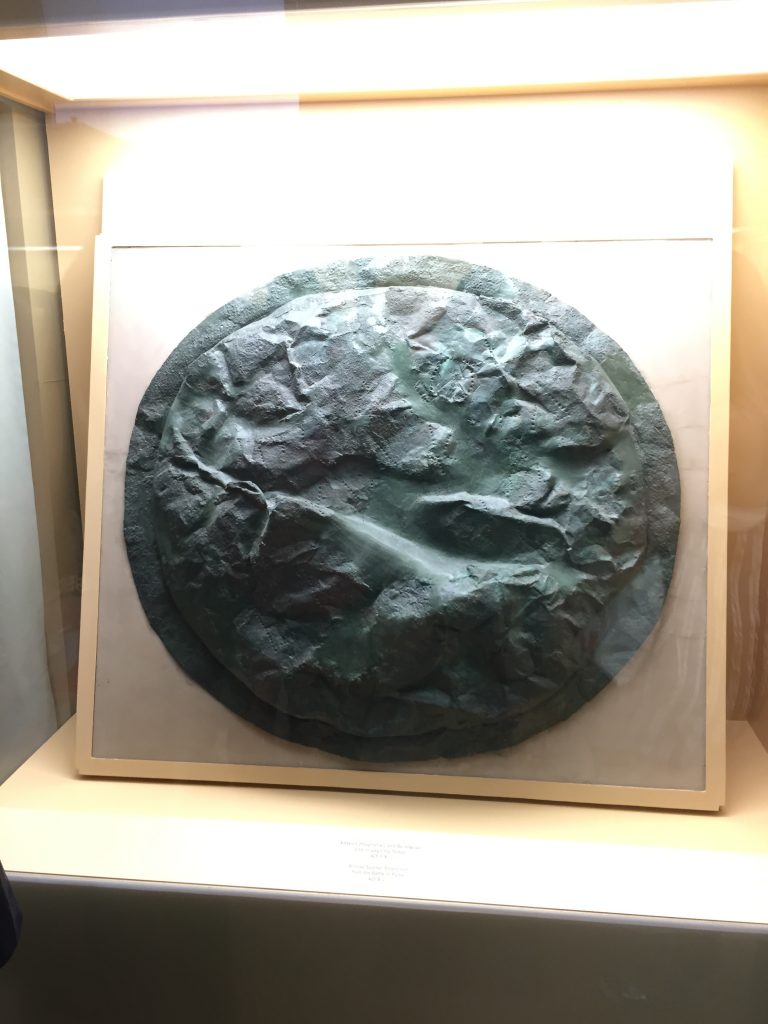

As for me, I made my way into the small museum that is housed on the ground floor of the stoa. Don’t let the size of this museum fool you. It houses a wonderful collection of artifacts from the full range of Athenian history in the agora from early Bronze Age tombs, through the Geometric period, the Classical period, and into the Hellenistic and Roman ages.

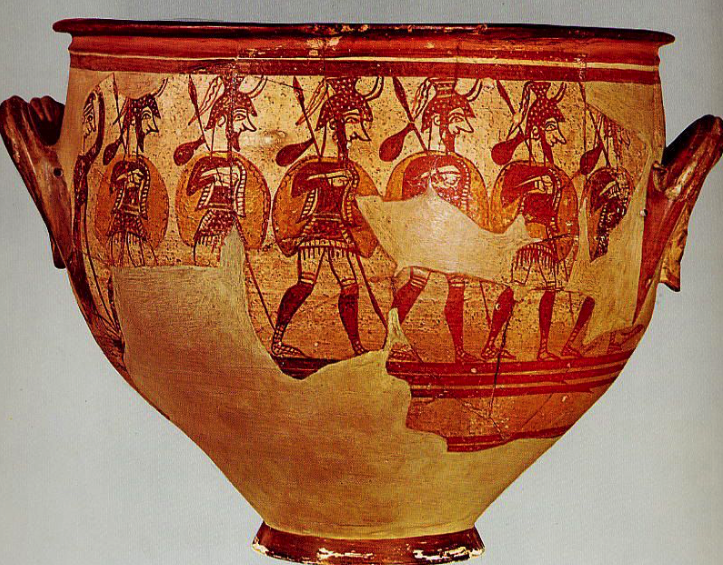

One of my favourite pieces was a three-handled bowl of which I had recently bought a wonderful replica from our friends at the Ceramotechnica Xipolias in ancient Epidaurus.

Here are a few of the wonderful artifacts that are in the museum of the ancient Agora:

After we were finished in the museum, there was one more surprise left in the stoa. If you go to the north or south end of the stoa you will see stairs leading to the second level.

We snaked our way up the stairs on the north end to find not only a wonderful view of the agora, but also, behind walls of glass, a long row of wooden shelves where myriad artifacts are stored. It was unbelievable to stand on the other side of the glass looking into the shadowed interior to see ancient black and red vases and kraters, kylixes and more. There were Mycenaean artifacts too, and all of it just sitting there silent witnesses to the ages gone past.

As we finished in the stoa and museum, we decided it was time to go. We made our way along a wall of broken monuments, displayed like ornaments in the garden of some antiquarian, each one with a story to tell of Athens’ past, each one whispering as I walked by.

I had to pull myself away from those voices, to tell them that I would see them again some day.

The day was wearing on, and there was more to do, more people to see before the end of my summer odyssey. But, I had to stand at the gates of the ancient Agora one more time and look out over the ruins of Athens’ history and up to the hopeful beacon of the Acropolis.

It is never easy to say goodbye to that ancient place, but I did so with a pang before turning and disappearing into the crowded market streets of Monastiraki and the Plaka, a part of me still wandering the Agora, haunted by history.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this short post on the agora of ancient Athens. If you did, you might also enjoy some previous posts on visits to Delphi, Delos, Tiryns, Epidaurus, Nemea, Eleusis, the temple of Apollo at Bassae, and Olympia.

Be sure to tune in next week as we step into the Hellenistic age with a guest post from historical fiction author Zenobia Neil.

Thank you for reading.

The World of The Dragon: Genesis – Part V – The Two Emperors of Rome

Welcome back to The World of The Dragon: Genesis. In our last post on the research that went into this latest book, we looked at the Evocati of ancient Rome. If you missed it, you can read it HERE.

The Dragon: Genesis spans the reigns of a few emperors. It begins during the reign of Antoninus Pius, but then moves on into unique period for Rome, a time when it was ruled jointly by two emperors, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Surprisingly, as we shall see, these two men ruled amicably, despite their differences. However, the peace of Antoninus’ reign was over, and the new emperors faced pressures and threats from outside.

First, we need to set the stage.

By the time Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus came to the imperial throne, the Roman Empire had enjoyed a period of unprecedented peace under the well-loved emperor, Antoninus Pius, who had reigned for the longest period of time since Augustus, from A.D. 138-161.

One of the only sources that survives for this period in Rome’s history is the Historia Augusta, a highly-contested, often doubted, source that relates some of the details of the reigns of certain of Rome’s emperors.

During Antoninus’ reign, a young Marcus Aurelius was already making himself known in the upper echelons of Roman society, so much so that he was a favourite of Emperor Hadrian before Antoninus Pius donned the purple.

It is believed that Emperor Hadrian would have liked for Marcus Aurelius to succeed him, but because of his young age, he chose Antoninus Pius. Prior to his death in A.D. 138, Hadrian, who cared much for the young Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, seems to have pressured Antoninus Pius into adopting them, thus ensuring their possible involvement in a later succession. Hadrian seems to have been a forward-thinking man.

Antoninus Pius, of course, agreed.

Marcus did not seem suitable, being at the time but eighteen years of age; and Hadrian chose for adoption Antoninus Pius, the uncle-in‑law of Marcus, with the provision that Pius should in turn adopt Marcus and that Marcus should adopt Lucius Commodus. And it was on the day that Verus was adopted that he dreamed that he had shoulders of ivory, and when he asked if they were capable of bearing a burden, he found them much stronger than before. When he discovered, moreover, that Antoninus had adopted him, he was appalled rather than overjoyed, and when told to move to the private home of Hadrian, reluctantly departed from his mother’s villa. And when the members of his household asked him why he was sorry to receive royal adoption, he enumerated to them the evil things that sovereignty involved.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Marcus Aurelius 5)

Then, in A.D. 140, Marcus Aurelius was made consul with Antoninus and given the title of ‘Caesar’ which officially made him Antoninus’ heir.

Now, Antoninus, who was married to Hadrian’s niece, Faustina (the Elder), did have four children, two sons and two daughters, but they all died young, except for his daughter Faustina (the Younger).

In A.D. 146, Marcus Aurelius was married to Faustina the Younger, further cementing his role as Antoninus’ successor, a role he is said not to have wanted.

As time passed, Antoninus Pius grew older and weaker, and Marcus Aurelius took on more administrative duties for the empire, especially after the death of Antoninus’ trusted Praetorian Prefect, Gavius Maximus.

Then, in A.D. 161, while at an estate in Etruria, Antoninus grew ill and called the imperial council together to formally pass the state to Marcus Aurelius. It is said that one of the last words he uttered when a tribune came to him for the night’s watchword was aequanimitas, or equanimity.

One has to wonder if Antoninus Pius really did feel a true sense of calm as he faced death, knowing that he had ruled well and that he was leaving the Empire in capable hands.

The reign of Marcus Aurelius was underway.

But Marcus Aurelius did not want to rule, and so the wheels were set in motion for the reign of two emperors and friends.

However, before we go further, let us look at these two men. Who were Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus?

Marcus Aurelius was born Marcus Annius Verus, and studies played a large role in the young man’s life. His teachers included Diognetus and Tuticius Proclus who seems to have introduced him to philosophy, a subject that Marcus took to immediately.

Philosophy played a large role in the life of Marcus Aurelius, affecting his life and his character. Even in A.D. 140 when he was made Emperor Antoninus’ heir, Marcus began studying with the sophist, Herodes Atticus, the man who built many monuments in Greece, including the great theatre beside the Acropolis of Athens. He also studied with Marcus Cornelius Fronto.

But it was the philosopher Quintus Junius Rusticus who is said to have introduced Marcus to the ways of stoicism that he would come to love and adhere to. Marcus Aurelius’ work, Meditations, was the product of his stoic view of the world and it is still widely read to this day.

One could say that stoicism is what got Marcus Aurelius through the more difficult times of his reign.

As far as a home life, Marcus Aurelius had thirteen children with his wife/cousin, Faustina the Younger, and among these were Lucilla and Commodus.

It seems that Hadrian’s favour of Marcus, and the condition he might have placed on Antoninus to adopt Marcus in order to succeed, weighed heavily on the young philosopher. Marcus was Antoninus’ sole heir, but when Antoninus died in A.D. 161, and the Senate made Marcus ‘Augustus’, ‘Imperator’, and ‘Pontifex Maximus’, it is said that he resisted. He preferred the philosophic life, but his stoicism compelled him to accept his duty, and despite his reluctance, he rose to the challenge:

Toward the people he acted just as one acts in a free state. He was at all times exceedingly reasonable both in restraining men from evil and in urging them to good, generous in rewarding and quick to forgive, thus making bad men good, and good men very good, and he even bore with unruffled temper the insolence of not a few.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Marcus Aurelius 12)

The Senate was going to confirm him as sole emperor, but Marcus refused unless Lucius Verus, his ‘brother’ beneath Antonius Pius, was given equal powers.

The Senate approved, and though officially, Marcus had more authority, Rome had two emperors for the very first time in its history: Imperator Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, and Imperator Lucius Aurelius Verus Augustus.

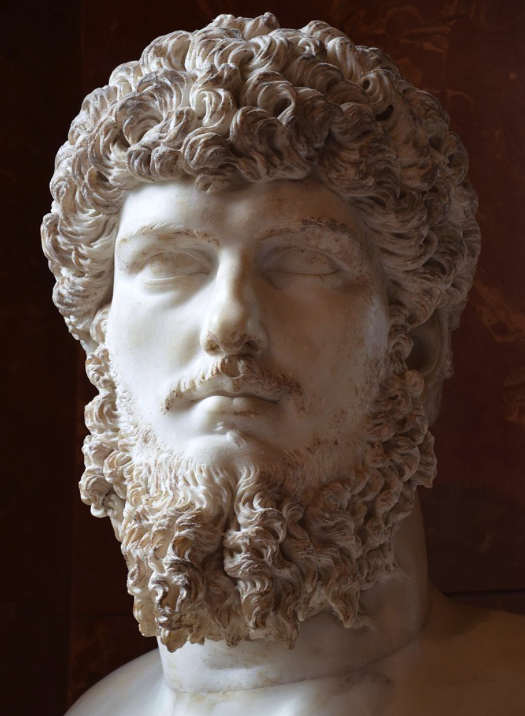

What do we know about Lucius Verus?

Apart from what the Historia Augusta tells us, we know relatively little about Marcus Aurelius’ co-ruler.

Born Lucius Ceionius Commodus (the Younger), he was a member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty, and his father, Lucius Aelius Caesar was Emperor Hadrian’s fist adopted son and heir. However, Verus’ father died in A.D. 138, and that is when Hadrian decided on Antoninus Pius as his successor.

Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius, though friends and ‘brothers’, appear to have been quite different.

Whereas Marcus Aurelius remains the calm stoic, preferring philosophy and a quieter life, Lucius Verus’ interests were said to be lower. He was fanatical about the games and chariot races, as well as gladiatorial combat, and he was said to enjoy lavish parties. He was quite the opposite of Marcus.

Lucius Ceionius Aelius Commodus Verus Antoninus — called Aelius by the wish of Hadrian, Verus and Antoninus because of his relationship to Antoninus — is not to be classed with either the good or the bad emperors. For, in the first place, it is agreed that if he did not bristle with vices, no more did he abound in virtues; and, in the second place, he enjoyed, not unrestricted power, but a sovereignty on like terms and equal dignity with Marcus, from whom he differed, however, as far as morals went, both in the laxity of his principles and the excessive licence of his life. For in character he was utterly ingenuous and unable to conceal a thing.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Lucius Verus 1)

Despite their differences, the two emperors seemed to have been able to make things work. It was as if they balanced each other. Marcus Aurelius is said to have disapproved of his co-ruler’s behaviour and vices, but he also saw that Lucius Verus fulfilled his imperial duties. Marcus even went so far as to betroth his eleven year old daughter, Lucilla, to Lucius Verus.

Things were looking bright in Rome. The emperors enjoyed the love of the people, and yet, there was great respect for the Senate and its traditions. Free speech was permitted, and the public service in government was running smoothly.

The reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, however, was not to be the period of Pax Romana that marked the golden age of Antonius Pius.

Sadly, the drums of war began to sound across the Empire.

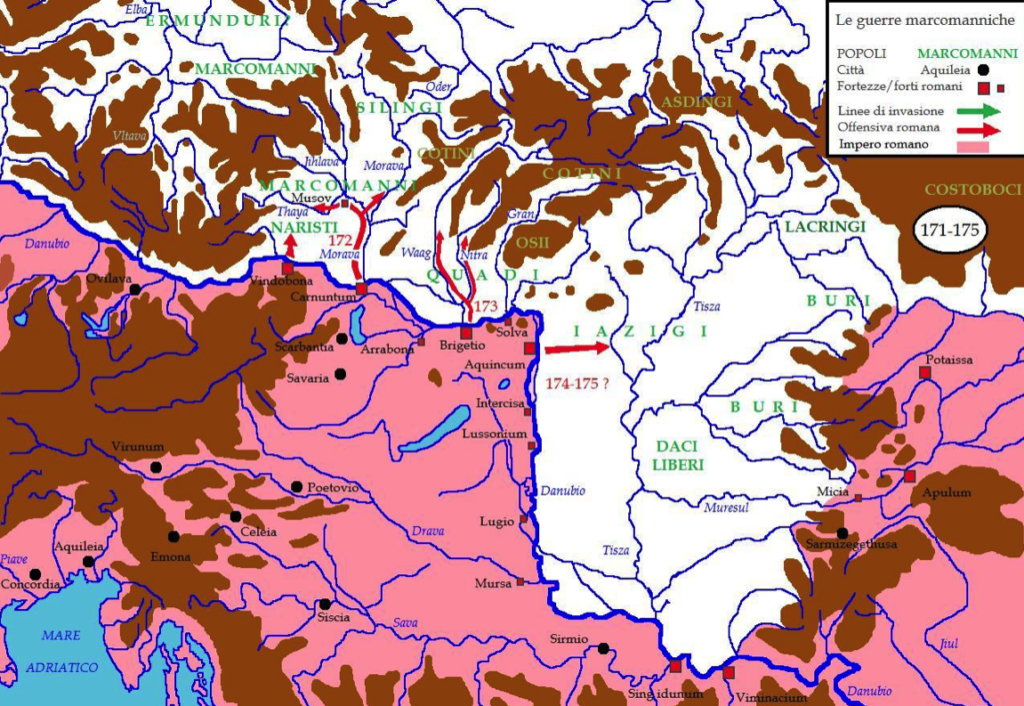

Two major wars marked the period: the Parthian war (A.D. 161 – 166) in the East, and the Marcomannic Wars (A.D. 166 – 180) in the North.

Because of aggressions shown by Vologasses IV of Parthia, and the subsequent massacre of one legion led by Marcus Severianus, the governor of Cappadocia, it was decided that Rome’s legions needed to march east.

The campaign was led by Lucius Verus, while Marcus Aurelius remained in Rome.

In fact, Verus spent most of his rule in Antioch, overseeing the Parthian campaign which was, in many ways, a success. Order was eventually restored.

It is said that Verus was a responsible commander and that he brought back discipline to the ranks of the Syrian legions who had grown soft during the prior peace. He was a good commander who knew when and how to delegate to men who were more knowledgeable, including his generals Marcus Claudius Fronto, and Martius Verus.

However, his vices followed him there, and in Antioch he is said to have lived a life of extreme luxury with grand parties. And he kept himself updated on the chariot racing in Rome by ordering regular reports sent to him about his favourite teams.

He also spend a great deal of time in the East with his mistress, Panthea, a low-born woman who was said to be a great beauty. Still, despite this, he did travel to Ephesus c. A.D. 163 to marry Marcus Aurelius’ daughter, Lucilla, who was only about fourteen at the time. She became Lucilla Augusta and they had three children together, all of whom died young. After the marriage, Verus returned to Antioch.

Lucius Verus certainly preferred bread and circuses to Marcus Aurelius’ love of learning and philosophy, but still, they seem to have worked well together.

When the Parthian campaign was successfully concluded, Lucius Verus was given the title of Parthicus Maximus. He and his men returned to Rome, but they were not only carrying coronae of victory with them. They also brought plague.

We will cover the ‘Antonine Plague’, as it is known, in the next post in this blog series, but suffice it to say, it was devastating.

And as Rome fought the plague at home, the Germanic tribes took the opportunity to attack in the North.

The Marcomannic Wars raged from A.D. 166 – 180 in a series of three major campaigns that took Rome’s legions across the Danube frontier against the rebellious tribes which included the Quadi, Marcomanni, Iazyges, Sarmatians, and the Dacians who had been peaceful for a time during the reign of Antoninus. It was an all-out offensive by the barbarian tribes.

This time, both Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus marched north with the legions to wage a war that would last the rest of their lives.

After two years of campaigning, the two emperors returned to Rome and it was then that Lucius Verus fell ill. Some said that it was food poisoning that killed him, but modern historians believe that it may well have been the plague that had returned with his men from Parthia.

Lucius Verus died and was grieved by Marcus Aurelius who, fittingly, put on games in his honour. He also had his co-emperor deified by the Senate as ‘Divus Verus’.

Marcus Aurelius now ruled alone.

After the death of Verus, Marcus Antoninus held the empire alone, a nobler man by far and more abounding in virtues, especially as he was no longer hampered by Verus’ faults, neither by those of excessive candour and hot-headed plain speaking, from which Verus suffered through natural folly, nor by those others which had particularly irked Marcus Antoninus even from his earliest years, the principles and habits of a depraved mind. Such was Marcus’ own repose of spirit that neither in grief nor in joy did he ever change countenance, being wholly given over to the Stoic philosophy, which he had not only learned from all the best masters, but also acquired for himself from every source.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Marcus Aurelius 16)

Marcus Aurelius has come down to us as one of the most noble emperors of Rome, the last of the ‘five good emperors’ as they have come to be known.

After the death of his friend and co-emperor, Marcus Aurelius brought the Marcomannic Wars to a successful conclusion. He also improved the judicial system as well as the system for distributing food. The management of the treasury was made more efficient too. He saw to the care of children, and constantly improved the civil service of which he had been a part in his early career. The Senate too, remained respected.

If he made one mistake during his reign, it was perhaps to trust his own son.

After the death of Lucius Verus and a period of lone rule, Marcus Aurelius named his son, Commodus, as co-ruler in A.D. 177. We will not go into the details of Commodus’ rule here. We need only know that it was nothing like his father’s reign, or Antoninus Pius’ before him.

Being the ruler of the greatest empire in the world could not have been an easy burden, especially for a man like Marcus Aurelius who had duty thrust upon him. This was in contrast to the life of thinking which he obviously preferred. In many ways, perhaps many of us can relate today. How many people live lives they had not intended for themselves?

Marcus Aurelius’ stoic philosophy no doubt helped him to come to terms with what fate had dealt him, but perhaps his insistence to the Senate that Lucius Verus rule with him was his way of alleviating some of the burden he felt?

It is difficult to say, but one thing we can be certain of is that, despite the lack of sources, the reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus will always stand out in the history of Rome as a time like no other.

If you have not read our latest historical fantasy novel, The Dragon: Genesis, you can download a free copy on the Eagles and Dragons website by CLICKING HERE.

Be sure to watch for the next post in The World of The Dragon: Genesis, where we will be taking a brief look at the effects of the Antonine Plague.

Thank you for reading.

Seven Outstanding Women from the Ancient and Medieval World

Hello History-Lovers!

This week on the blog we’ve got a special post about some amazing women from ancient and medieval history.

As has often been the case in history books and classes, the focus of historical personages has been male-oriented. Men declared most wars, made political decisions, ruled, and basically determined the future for numerous societies, kingdoms and empires.

While there have been some amazing men in history, there have also been many incredible women who have displayed great strength, resilience, and courage on the world scene, women who have set a shining example and challenged the status quo.

Over my years of study, I can’t remember how many times I’ve come across a woman from history who blew my mind with their daring, but whose life was rarely explored in-depth in any of my courses or the books I read. With hope, curricula in high school and beyond have changed to more properly reflect the role of women in history.

There are far too many outstanding women in history for me to list them here, but with this post I wanted to introduce you to a small group of women who have left a great impression upon me, personally, during my years of study, research and writing. The biographies below will be brief, but I hope they encourage you to read more.

Kyniska of Sparta

396 B.C.

Those of you who have read Heart of Fire will be familiar with Kyniska of Sparta, one of the main protagonists of the story. The very first time I read about this Spartan princess, I knew immediately that I had to write a story around her achievements.

Kyniska of Sparta was the daughter of King Archidamus II (476-427 B.C.), the Eurypontid King of Sparta. She was also the half-sister of King Agis, and sister to King Agesilaus II (444-360 B.C.) who waged war on both the Persians and his fellow Greeks.

It is believed that Kyniska was born sometime around 440 B.C. in Sparta and, unlike other Greek women beyond Sparta, she grew up training herself physically and mentally, as was expected of strong, Spartan women.

What makes her so special?

Well, in addition to winning in the foot race at the Heraian Games that took place at Olympia, she was also the first woman in history to win at the Olympic Games when she entered her team in the four horse chariot event. And not only did she win, she did it at two Olympiads in 396 B.C. and 392 B.C.!

When I first wrote about Kyniska, some people, including women, told me that her achievements didn’t mean much since she did not drive the chariot herself. However, my answer to that is that that is a modern perspective only. We have to keep in mind that in the world Kyniska inhabited, women were considered to be very little, other than chattel. They had no say, no involvement in affairs of war or state, and certainly no place in the Olympic Games, not even being permitted within the sacred sanctuary of the Altis, unless they were a priestess.

For someone like Kyniska to raise and train her horses – which she did – and then to enter the Olympics to compete against the richest and most powerful men of the city-states of the Greek world took no little amount of courage.

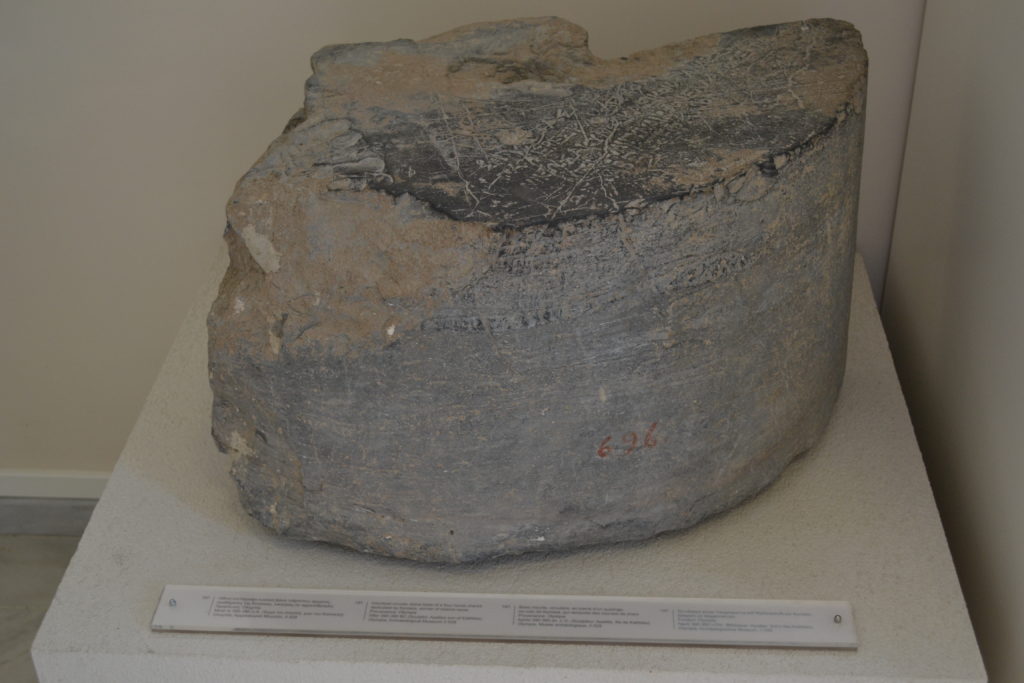

Inscribed base for the victory statue commemorating Kyniska’s victory at the Olympic Games. It is now located in a small room at the Museum of the Olympic Games in ancient Olympia, Greece. It was amazing to see this piece of stone that represented such an earth-shattering change in Olympic history!

Kyniska’s actions show that she was a strong, willful and outspoken woman in the highly misogynistic world of ancient Greece, and of Sparta.

She also opened the doors to other women to compete in the Olympic Games, includingEuryleonis, in 368 B.C., who also makes an appearance in the story of Heart of Fire. Women from other city-states, including Belistiche, Zeuxo, Encrateia, Hermione, Timareta, Theodota of Elis, and Cassia, also eventually competed and won.

For me, Kyniska is a hero of ancient history!

If you would like to read more about Kyniska of Sparta, you can CLICK HERE for the full blog post on her. You can also read about her in Heart of Fire: A Novel of the Ancient Olympics which features her achievement at the Olympiad of 396 B.C.

Olympias

375 – 316 B.C.

One name that conjures images of motherly pride, female strength, and perhaps illustrates the words ‘hell a fury like a woman scorned’ better than any other is that of Olympias, the wife of King Philip II of Macedon, and the mother of none other than Alexander III (the Great).

One thing that many great women in history seem to have in common is that they have been demonized by history, and male historians, to an extent. Olympias is certainly no exception.

As the daughter of Neoptolemus I of Epirus, King of the Molossians, Olympias was descended (and she fervently believed it!) from the Greek hero, Achilles.

She was a strong, passionate and imperious woman in the male-dominated world of ancient Greece. She was also a dedicated worshipper of Dionysus, there being many tales of her ecstatic, mad dances in honour of the god.

In 357 B.C., she married Philip of Macedon and quickly proved to be no typical wife of ancient Greece. She was not one to be locked away, or to remain silent. She and Philip were often at odds, and when he took another wife, she returned to her home in Epirus. Philip was murdered of course, and some say that she had a hand in that so as to secure the position of her son, Alexander, upon the throne.

It was also said that Olympias also murdered that wife of Philip’s, as well as the son she more.

One thing is for sure – you would not want to get in the way of this Greek mother and her son.

While Alexander was conquering lands all the way to India, Olympias fought to protect his back, and was often at odds with Alexander’s regent, Antipater, whom Olympias did not trust to look out for Alexander’s interests.

Not welcome in Macedon during Alexander’s absence, Olympias returned once more to Epirus to rule alongside her daughter, Cleopatra.

It would be difficult to call Olympias an expert at diplomacy, though she was a shrewd politician and seems to have had a knack for knowing who could or could not be trusted with her son’s interests.

Olympias was more of a force of nature, and after Alexander’s death, she returned to Macedon in 319 B.C. to support Polyperchon against Cassander, Antipater’s son, and one of Alexander’s generals.

Despite her grief over the death of her beloved son – a son some believed was actually the son of Zeus – her goal was to secure the inheritance of her grandson, Alexander IV. Olympias gave Roxana, Alexander’s wife, and her son her protection, and promptly went to war against Cassander. She won many battles in this war, a war she fought on behalf of her family.

But she was, apparently, too brutal.

When Cassander captured her at Pydna, she was put to death by the families of her victims over the years.

Here, it is important to note that Cassander’s soldiers refused to hurt her. They would not be the executioners of Alexander’s mother.

Whatever you might think of Olympias, there is no doubt that she was the ultimate woman of strength and determination, a woman who could well have lived up to her shared blood with Achilles himself.

If you are looking for a relatively accurate portrayal of Olympias, you might want to check out Oliver Stone’s epic film, Alexander, in which she is portrayed by Angelina Jolie. The historical advisor on the film was Robin Lane Fox, one of the definitive biographers of Alexander the Great. You can find Fox’s book HERE.

If you’re looking for novels, Valerio Massimo Manfredi’s Alexander Trilogy is a great read.

Cleopatra VII Philopator

69 – 30 B.C.

The name of Cleopatra needs no introduction. She is perhaps the most famous (and final) queen of ancient Egypt, portrayed in art, literature, and modern media countless times.

However, many portrayals of this last ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty have been extremely unfair and, frankly, insulting. One example is the HBO series Rome. As much as I loved that show, the portrayal of Cleopatra as a sort of nymphomaniac junkie could not have been further from the truth.

If that is the case, who was the real Cleopatra, other than a descendent of Alexander the Great’s general, Ptolemy, and a lover of Julius Caesar and Marcus Antonius?

She was royalty, and she was a survivor. She was also well-educated, a cunning diplomat, and a skilled naval commander. She was also highly intelligent, being fluent in several languages – she was the only Ptolemaic pharaoh fully fluent in the Egyptian language of her people!

Cleopatra was a brighter star than most of the rulers of her family dynasty. She was a champion of her people, and she sought to secure their future by any means necessary, going so far as to become the mistress of another rising star on the world stage, Julius Caesar, whom she bore a son named Caesarion.

When she and her son arrived in Rome in 46 B.C. their entrance became legend, but she was only to remain there until 44 B.C. when Caesar was murdered. After that, her son, and Egypt, were at the forefront of her thoughts, and she set about securing her position and that of her son by any means, including poisoning her younger brother.

Cleopatra finds herself in legend again with the subsequent romance between her and Marcus Antonius, and this affair has been written of, painted, and poeticized again and again. Sometimes the telling is quite romantic, but it is foolish to believe that the great women of history were only as great as their affairs, I think.

She became a mother yet again, this time giving Antonius three children – Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus. Though the accounts speak of love between Antonius and her, Cleopatra, during this time, negotiated the return of Egypts lost lands, and then obtained new lands, from Rome.

In the West, however, Cleopatra’s influence on Antonius and her imperial ambitions caused Octavian to begin a smear campaign against her that, to this day, taints our perception of her.

Things came to a head at the battle of Actium, in which Octavian’s forces defeated those of Cleopatra. The end was near. It should be said here that there is no evidence that she fled the battle when it appeared lost. That was perhaps another fabrication of Octavian’s propaganda machine.

When they returned to Egypt after the battle, Antonius, like a good Roman, committed suicide.

Seeing Octavian closing in, and refusing to be an ornament in his triumph in Rome, Cleopatra, the last ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty, committed suicide by snake bite on August 10th, 30 B.C. Her children by Antonius were spared and raised by his Roman wife, Octavia, but her son, Caesarion, was murdered.

Thus ended the Hellenistic Age that had begun with Alexander the Great.

Some people love Cleopatra, others hate her. But there is no denying that she was a passionate woman of extremes. She certainly owned her role as Egypt’s queen, and fought hard for herself, her people, her kingdom, and for those whom she loved.

In reaching so high, she was perhaps burned by the sun, but it is indeed hard to imagine anyone else capable of so much!

If you would like to read more about Cleopatra, you should definitely check out the biography, Cleopatra, by Michael Grant.

And as far as films, I still love the epic classic Cleopatra with Elizabeth Taylor.

Livia Drusilla

58 B.C. – A.D. 29

If were are talking about the strong women behind the men who ruled the world, we would be remiss if we did not include Livia Drusilla, later Livia Augusta, first empress of the Roman Empire.

Many of you might know of Livia from the BBC drama, I Claudius. She was not only a great power behind the imperial throne, and not a woman to be trifled with, she was also the matriarch of one of the most famous dynasties of ancient Rome.

I’ve always been curious about Livia and her world, amazed by the power she seemed to have wielded over the rulers of Rome. She was the wife of Emperor Augustus for fifty-two years, and as such she helped to build a new, Roman world.

She was also the mother of Emperor Tiberius, the grandmother of Emperor Claudius who deified her, the great-grandmother of Emperor Gaius (the infamous Caligula), and the great-great-grandmother of Emperor Nero.

If there is a supreme example of the Roman mater familias, Livia is it.

She met Octavian (future Augustus) in 38 B.C. and married him. By all accounts, she captured his heart, but she also gave him a great deal of strength.

Morals and traditions were important to the Romans, and Livia excelled at these, being a dutiful wife and mother in the eyes of the Roman people.

But she also helped Augustus with his dynastic plans. An Empire cannot be born without crises, and Livia helped her husband to weather them all.

She played a more prominent role in state and family affairs than any Roman woman before her.

Livia was extremely intelligent and perceptive, and she was Augustus’ most loyal, trusted advisor. In fact, it’s even possible that his reign would not have lasted so long without her. Together, they spearheaded what was thought to be a return to true Roman morality.

The ‘Grand Cameo of France’ artifact showing the Julio-Claudian Family, including Livia beside her enthroned son, Tiberius

However, there were rumours of her plotting to secure her son Tiberius’ accession to the throne by murdering several of Augustus’ possible heirs. Odd that once Tiberius came to the throne, the two were estranged.

Caligula, who lived with her for a time, is said to have called her a cunning intriguer, ‘Odysseus in a dress’!

To have survived for so long in the world of ancient Rome and all the dynastic family struggles that entailed, and to have been at the forefront of the creation of one of the world’s greatest empires, I think it can truly be said that Livia Drusilla was an exceptional woman deserving of her deification.

She also cleared the way for other strong women of Rome who followed in her footsteps.

For a wonderful portrayal of Livia in film, you should definitely watch the BBC mini series of I, Claudius, in which this titan of ancient Rome is expertly played by Sian Philips.

The Robert Graves book of I, Claudius, which the television series is based on, is a wonderful read too, and though it perhaps takes some poetic exaggeration, it is a fantastic book.

Boudicca – Queen of the Iceni

A.D. 60

When I think of strong women from the ancient world, Boudicca is at the forefront of my mind. I can see her now, tall, standing on her war chariot, her red hair blowing in the wind, and vengeance in her eyes.

Her acts are inspiring and heroic, and her story one of tragedy.

Boudicca was the wife of King Prasutagus of the Iceni nation of Celts, who ruled the area of modern day Norfolk. Prasutagus was a client king of Rome at the time, but upon his death, he left half of his possessions to Emperor Nero.

It did not take long for the Roman officials to descend on the Iceni to seize everything. More than that, they flogged Boudicca publicly and raped her two daughters.

Boudicca’s story is one of horror and war, and to me, her name is synonymous with rage and swift vengeance.

After these grievous attacks upon herself, her daughters, and her people, Boudicca rallied the Iceni nation, as well as the neighbouring Trinovantes (in modern Essex and Suffolk), and moved against the Romans.

With an army of one hundred-thousand, Boudicca sacked the cities of Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium (London), and Verulamium (St. Albans), the most important towns in southern Britannia. Her forces killed seventy to eighty thousand Romans and Britons living in those towns, and they went on to trounce forces from the IX Hispana Legion.

But her time of glory and vengeance was fleeting.

The governor of Britannia, Suetonius Paulinus, who had been suppressing the Druid rebellion on the Isle of Anglesey, rushed into the fray to meet Boudicca in battle. His legions included the XIV Gemina, XX Valeria Victrix, and the II Augusta.

Boudicca must have known that they could not win against three legions, but rather than submit to Rome, she and her army met them head-on in the Battle of Watling Street. Despite the Romans being outnumbered, the legions’ discipline and Suetonius’ generalship won the day, and the Queen of the Iceni died by poison before being taken.

The Boudiccan rebellion was over, but like the Spartacan revolt during the Roman Republic, it left a mark on the Roman psyche, and the battle cry of the Iceni queen would reverberate for generations to come.

Boudicca, for me, is the epitome of the Celtic warrior queen. She stood up to the might of Rome, and became an important cultural symbol for the United Kingdom in later centuries.

What we know of her comes only from the writings of the Roman conquerors, but her deeds speak for themselves!

If you are interested in reading a great series of novels about the Boudiccan rebellion, I recommend Manda Scott’s wonderful Boudicca series, beginning with the first book, Dreaming the Eagle.

Julia Domna

A.D. 160 – 217

Julia Domna, Empress of the Roman Empire and wife of Septimius Severus, may not be on your own list of outstanding women of history, but she is someone I have developed a deep respect for over the years.

Those of you who are familiar with the Eagles and Dragons series will know that Julia Domna plays a prominent role in the novels. Having researched and written about her for so long, I feel like I have developed a grasp of her role as empress at a time when the Roman Empire was at its greatest extent.

She appears as one of the strongest women in Rome’s history, an equal partner in power with her husband who heeded her advice but also respected her.

Julia Domna was the first of the so-called ‘Syrian women’, she and her sisters hailing from Antioch where their father had been the respected high priest of Baal at Emesa (Homs in modern Syria).

Julia Domna was also highly intelligent, known as a philosopher, and had a group of leading scholars and rhetoricians about her. They came from around the Empire to be a part of her circle or salon, to win commissions from her. Her strength also bought her a great many enemies, including the Praetorian Prefect and kinsman to Severus, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. The conflict between the Empress and the Prefect of the Guard is something that is explored a good deal in Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra.

Not only did Julia Domna carry on the tradition of the strong, involved Roman empress that was begun by Livia Drusilla, she did so perhaps with an openness that gained her some loyal followers. Despite the fact that she was not Roman, she had earned a great deal of respect across the Empire.

Sadly, her sons Caracalla and Geta proved to be lesser mortals than their mother, but she helped to ensure that the Severan dynasty weathered the threats from outside, and in, for a time, paving the way for her sister Julia Maesa, and her neice, Julia Mamaea, both of whom followed in her footsteps as strong, ruling women.

If you would like to read more about Julia Domna and the Severans, be sure to read the blog post by CLICKING HERE. In addition to the Eagles and Dragons series, I highly recommend Michael Grant’s excellent book The Severans: The Changed Roman Empire.

Eleanor of Aquitaine

A.D. 1124 – 1204

For the last person on our list of incredible, kick-ass women of history, we head into the Middle Ages to meet my favourite person of the medieval period, Eleanor of Aquitaine.

It is an impossible task to summarize the life of this incredible woman in a few short paragraphs. Her life was long, and full, the stuff of legend really. She was a wife of kings, and a mother to kings, but she was also much more than that.

Eleanor hailed from the southwest of what is today, France, in the extremely rich and fertile region known as the Aquitaine. She was a passionate and high-spirited woman, so much so that her nature was not to the taste of the reserved northerners. Despite this, however, she was married to King Louis VII of France from 1137-1152, during which time she gave him two daughters as Queen Consort of France.

Eleanor was a sort of rebel in language, behaviour, and fashion at the time, and was even criticised by the church and her royal in-laws for it. But her reserved husband was smitten by her liveliness and beauty, and so she did as she chose. She was even scolded by Bernard of Clairvaux for her constant interference in matters of state, a scolding she did not take to heart, it seemed.

In 1145, when King Louis set off on the Second Crusade as a penance for a massacre at Vitry, in France, Eleanor proved that she was not one to sit idly by at home while he went to war. No sidelines for her!

Along with her ladies in waiting, and three hundred soldiers from Aquitaine – which she ensured remained independent of France – Eleanor took up the cross herself and went East with her husband. And, as legend has it, she and her ladies dressed as Amazon warriors to ride to battle, earning her the title of the next Penthesilea, Queen of the Amazons when they arrived in Constantinople, the great city of the eastern Empire.

But the Holy Land was not what she had thought, and though she wished to stay with her uncle, the indomitable crusader, Raymond de Toulouse, in Antioch, Louis dragged her to Jerusalem after rumours of her relationship with her uncle emerged. As a result, she and Louis became more and more estranged, so much so that she went to the Pope himself to ask that the marriage be dissolved. When she gave birth to yet another daughter – by Louis, she had Marie and Alix – Louis finally agreed, and Eleanor was free of the marriage, though she ensured that she kept the Aquitaine.

All of a sudden, Eleanor was the most sought-after bride in all of Europe. It was at this point that men such as the Count of Blois and the Count of Nantes tried to kidnap her and take her for themselves. But Eleanor would have none of it and so, she made a strategic move of her own. She headed for Poitiers where she contacted the Duke of Normandy (future Henry II of England) and asked him to marry her!

And so, in 1152, Henry and Eleanor were married, and in 1154 they became king and queen of England.

Henry was by all accounts a willful and powerful man, and in Eleanor, he had met his match. Their marriage was tumultuous to say the least. Henry had numerous affairs but she took it all in stride. She was tough, and throughout their marriage she held onto the Aquitaine, the people of which refused Henry’s overlordship and acknowledged only Eleanor’s authority.

Eleanor of Aquitaine was a great woman, perhaps married to lesser men, at least in Louis anyway, but she also gave birth to two sons who would end up being some of the most famous kings of England – Richard the Lionheart, and King John.

She fought hard for her sons, even waging war against Henry himself on their behalf. She was always at work on affairs of state for them, on the front lines of diplomacy, or strategizing in the background. Even at the age of seventy-seven, Eleanor was travelling and negotiating on behalf of her son, King John!

In the end, however, it seemed her sons were lesser people than her.

To me, Eleanor of Aquitaine’s influence and deeds do not revolve around her husbands and sons, but more importantly around the cultural revolution she influenced and nurtured in Poitier.

At her Court of Love, from about 1168-1173, while far away from Henry II, Eleanor and her daughter, Marie de Champagne, encouraged and patronized the troubadours of France. Poets and artists flocked to her court, and out of that were born the ideals of chivalry, courtly love, and tales of Arthurian Romance that we are familiar with today.

Eleanor of Aquitaine, like many other strong women of history, was slandered and demonized by others the whole of her life, but she carried on as she believed. She was a strong, passionate, daring and revolutionary woman, and she should be lauded for that.

She stood up to the world of men, especially those she believed not her equals. Her people loved her, and she was one of the founders of a cultural revolution that was a bright light in darker times. If there was a medieval feminist warrior, I think it might just be her.

She is definitely one of my favourite women of history!

If you want to read more about Eleanor of Aquitaine, I highly recommend the book by Amy Kelly, Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Four Kings. You won’t regret it.

Also, to read more about Arthurian Romance and Eleanor’s Courts of Love, you may want to check out Arthurian Romance and the Knightly Ideal.

If movies are more your thing, you should definitely watch The Lion in Winter which has an all-star cast, including Katherine Hepburn as Eleanor of Aquitaine.

I hope you have enjoyed this post on my own favourite women from ancient and medieval history.

I know that this has been my perspective as a man, but in all of my years of study, this group has left a lasting impression on me. There are so many more, I know. Hypatia of Alexandria certainly springs to mind…or Nefertiti… Joan of Arc, etc. etc… So many.

I suppose the point is that we need to look at all examples of human achievement in history that inspire us to excel in our chosen lives.

This was just a small sample.

Now, tell us, which women of history would you put on your list?

Let us know in the comments below.

Thank you for reading.

The Pylos Combat Agate and the Griffin Warrior Tomb

They came to Pylos, Neleus’ strong-founded citadel, where the people on the shore of the sea were making sacrifice of bulls who were all black to the dark-haired Earthshaker. There were nine settlements of them, and in each five hundred holdings, and from each of these nine bulls were provided.(The Odyssey)

Pylos is a name out of time and legend, immortalized by Homer in the Iliad and the Odyssey, as was the name of Nestor, the son of Neleus and Agamemnon’s right-hand man and aged advisor during the war with Troy.

When you look at the archaeology of the Mycenaean Bronze Age in Greece, one inevitably thinks of places such as Mycenae, Tyrins, and yes, Pylos. These sites are well known.

There is, however, a misconception outside of the world of archaeology that everything has already been found.

This is far from the truth. Archaeologists are excavating new finds all the time, sometimes aided by drought and fire, other times by desperately-needed funding to back strong theories or even hunches about locations.

Pylos is no exception.

In the world of ancient Greece, one of the most exciting finds in the last few years is that of the Pylos Combat Agate and the discovery of the Griffin Warrior Tomb.

In today’s post, we’re going to take a look at the tomb and the array of magnificent finds that are challenging previous notions of the evolution of ancient Greek art.

First off, what exactly is at the site of Pylos?

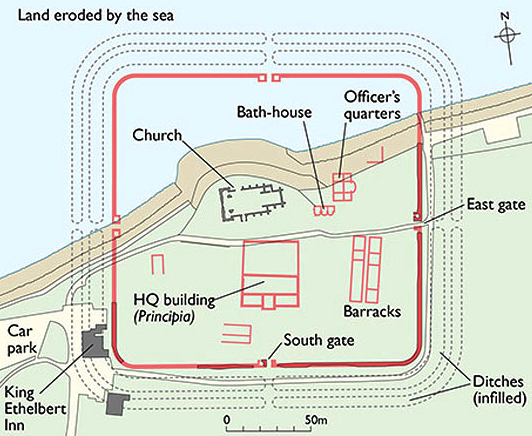

View of the megaron in the Palace of Nestor at Pylos, published by Carl Blegen in the AJA in 1956 before the first roof over the palace was built (image copyright held by the Department of Classics at the University of Cincinnati)

Pylos is located in the southwest of the Peloponnesian mainland of Greece. The palace there is the best-preserved Mycenaean palace yet discovered, said to be the power centre of King Nestor, whose ships joined the Greek army sailing for doomed Troy.

The palace of Pylos was located on a hill within the larger settlement that was, it is supposed, surrounded by an outer wall. It was made up of two storeys with various rooms, workshops, baths, reception rooms, and even a sewage system.

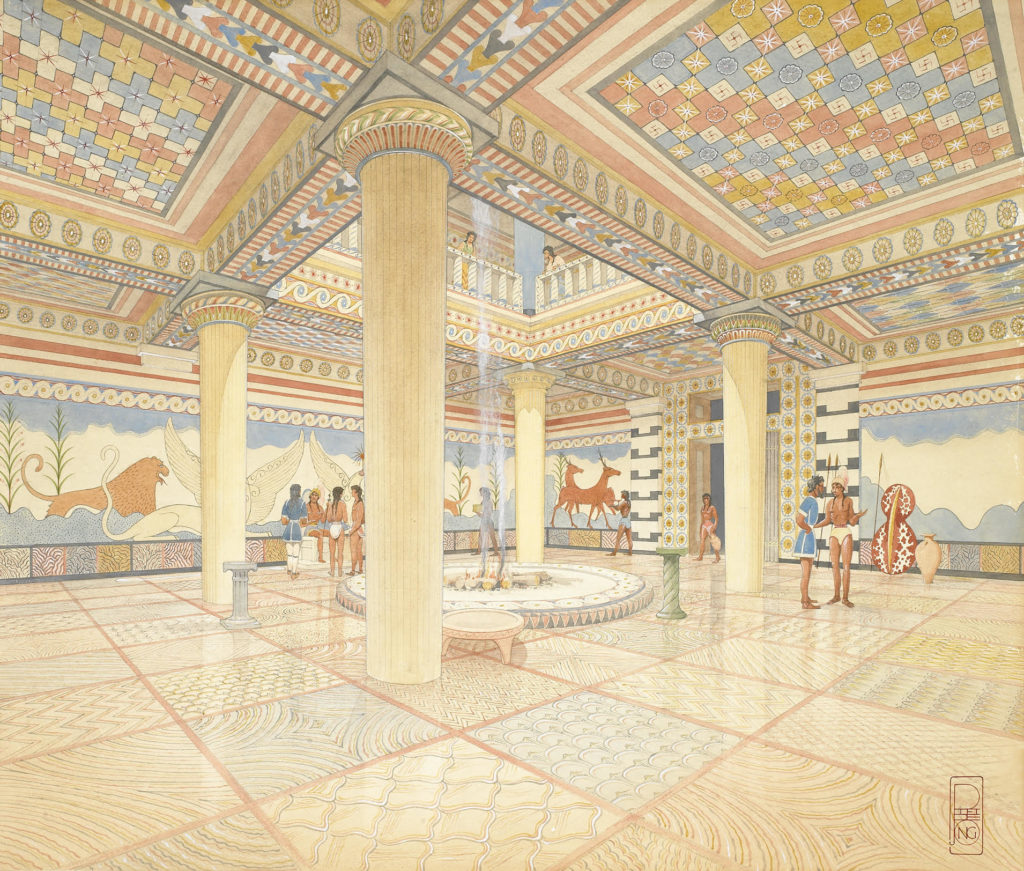

Watercolor reconstruction of the Throne room of Nestor’s Palace by artist, Piet de Jong (Image copyright by the Department of Classics at the University of Cincinnati)

Excavations at Pylos occurred in 1912 and 1926 when two tholos tombs were discovered in the area, but it was in 1939 that a proper, joint Greek-American excavation got underway. This was led by famed archaeologist Carl Blegen, from the University of Cincinnati. Blegen’s initial excavations of Pylos revealed walls, frescoes, Mycenaean pottery, and a royal archive of one thousand tablets.

World War II put the dig on hold for a while, but you can’t keep determined archaeologists down! In 1952, the palace was finally uncovered.

I’ve not been to this site personally yet, but it is definitely on my ‘to visit’ list! Here is a virtual tour of the palace at Pylos:

The University of Cincinnati has continued to excavate at Pylos since Blegen first became involved, more recently under the leadership of the archaeological husband-and-wife team of Jack L. Davis and Sharon Stocker who are responsible for the recent and fascinating discovery of what has become known as the ‘Griffin Warrior Tomb’.

What is the Griffin Warrior Tomb?

It is an undisturbed (and un-looted!) shaft tomb dating to about 1450 B.C. (before the Trojan War). It contained the intact remains of a long-haired adult male of thirty-something, of about 5 ½ feet tall, whose wooden coffin was located in the tomb along with over 3500 grave goods.

Sword and Ring from the Tomb (image copyright by the Department of Classics of the University of Cincinnati)

The grave finds included bronze weapons, armour, jewels and jewellery, mirrors, many items of silver and gold, signet rings, ivory combs, boar tusks (perhaps from a helmet), and more. It is interesting and important to note here that some of the goods are decorated with uniquely Minoan motifs.

There was also an ivory plaque between the warrior’s legs with a carved relief of a griffin. Presumably, this is where they came up with the name of this tomb.

Artist recreation of the Griffin Warrior Tomb as excavated (image copyright by the Department of Classics of the University of Cincinnati)

The tomb was located in an olive grove near the palace of Nestor, but within the Bronze Age city of Pylos.

We have no idea who this man was, but it seems likely that he was a warrior who was both rich and important. It is telling that he was buried not with many ceramic goods, which is common for warrior graves from the age, but rather with much gold and silver and finely wrought weapons. It is also thought that he could have been a priest of sorts due to the fact that many of the grave goods are ritual objects.

Grave finds of Griffin Warrior Tomb (image copyright by the Department of Classics of the University of Cincinnati)

Project co-directors Sharon R. Stocker and Jack L. Davis of the University of Cincinnati note: “The team did not discover the grave of the legendary King Nestor, who headed a contingent in the Greek forces at Troy. Nor did it find the grave of his father, Neleus. They found something perhaps of even greater importance: the tomb of one of the powerful men who laid foundations for the Mycenaean civilization, the earliest in Europe.”

This is pretty exciting!

More research and analysis of the finds is, of course, already underway. The exciting thing is that it is thought that more will be discovered about the relationship between the Mycenaean mainland and Minoan Crete.

I’m only summarizing things here. There is a lot more to read about this excavation and the finds and I’ll provide some links at the end of the blog.

Before I do, however, I wanted to touch on the one find that has truly captured the imagination of many around the world, especially my own…

The Pylos Combat Agate.

Here it is:

Image of the Pylos Combat Agate (image copyright by the Department of Classics of the University of Cincinnati)

Isn’t it stunning? Of all the wonderful finds in the Griffin Warrior Tomb, this is the one that pulls me in.

What is it?

At this point, it’s thought to be a Minoan seal that was created around c. 1450 B.C.

It’s named for the fierce combat that it portrays, and is now considered the best work of glyptic art (a symbolic figure carved or incised in relief) ever from the Aegean Bronze Age. In fact, such quality, skilled work in this style was not seen until the Classical Age about a thousand years later!

Who made this gem, and what is the scene being portrayed? Now that’s story to consider!

Pylos Combat Agate before restoration (image copyright by the Department of Classics of the University of Cincinnati)

This magnificent artifact is made of agate and is about 3.4 centimeters (1.3 inches) wide. In the Griffin Warrior Tomb, it was found along with four other signet rings with other engravings such as Minoan bulls.

It is believed that this was obtained from Minoan Crete by Mycenaeans, either by import or theft.

Artist Sketch of the Pylos Combat Agate Scene (image copyright by the Department of Classics of the University of Cincinnati)

Science, archaeology, and history aside…how does this scene make you feel?

The scene depicted is of a vicious battle with an unarmoured, long-haired warrior engaged in a brutal combat with a heavily armoured warrior. The former stands upon the body of a man he has already slain.

We don’t know anything else about this artifact, and we probably never will. But the possibilities are thrilling, aren’t they?

That’s one thing I love about archaeology – the potential for stories.

Every one of the artifacts found in the Griffin Warrior Tomb has a story behind it – how it was made and why, by whom? How did the artifacts come to be in the possession of this wealthy warrior and what meaning did they hold for him?

You can go on and on. Truly, there’s an entire book series to be written about this one man!

I was so inspired last year by the discovery of this artifact that I wrote an ‘Inspired by the Past’ short story about it which is available to all Centurion-level supporters on the Eagles and Dragons Publishing Patreon page.

Jonida Martini and Sharon Stocker excavating the upper layer of artifacts immediately after bronze was discovered. (image copyright by the Department of Classics of the University of Cincinnati)

I’ve only scratched the surface of the history and finds related to the Griffin Warrior Tomb at Pylos, but I hope you’ve found it interesting and that it has inspired you to discover more.

To find out more about the archaeological team, the project and finds, I highly recommend visiting the website set up for the project at: http://www.griffinwarrior.org/griffinwarrior-burial.html

You can also watch the interviews on Greek media with the lead archaeologists on the project, Jack L. Davis and Sharon Stocker. Their excitement and enthusiasm for the finds is contagious and inspiring! Check out the video below (and cue the dramatic Greek news show music!)

Thank you for reading!

Ancient Everyday – The Siesta

Salvete, dear readers!

I hope you’re all having a brilliant summer so far, or winter if you’re in the southern hemisphere!

The extreme heat that’s been hitting much of the world has not by-passed Toronto either. The air has been thick and humid on several occasions, causing folks to drag their feet and stay indoors if they can, or to seek out the nearest body of water to cool off.

It’s amazing how the heat can drain one’s energy!

So, that got me to thinking about a new Ancient Everyday! If you missed the last post on pets, you can check it out HERE.

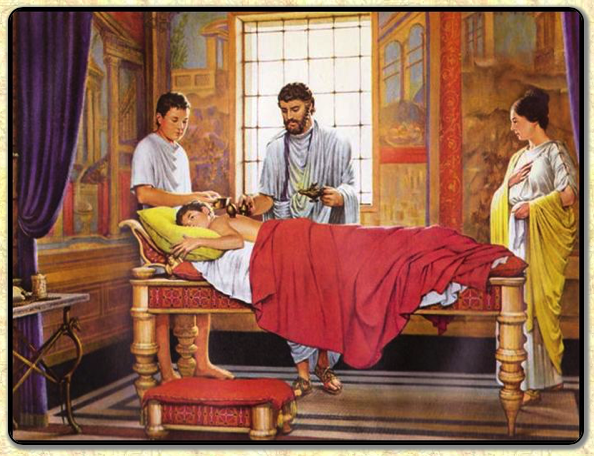

Today, we’re going to take a brief look at the siesta!

The idea of the siesta was not something I grew up with. Few people do in North America. You get up, you work through the day, or go to school, and then you come home, eat and sleep.

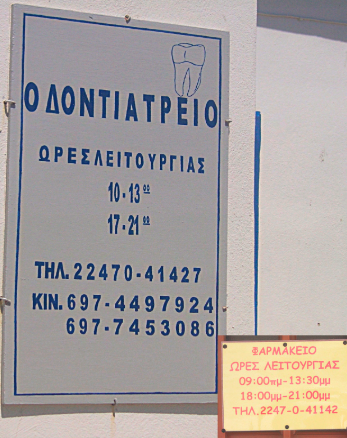

Most people associate the siesta with Spain or other Spanish-speaking countries, but I first came across the siesta when visiting Greece years ago. As ever, I was out doing the tourist thing, baking myself among the ruins of various archaeological sites, when the world seemed to grow quiet around 2 p.m. or so.

It was midday, but everyone seemed to have retreated. Businesses closed and restaurants emptied (except in the very touristy locations like the Plaka of Athens). There seemed to be a general hush over the world.

It was surreal. It felt like I was in some apocalyptic movie, the only person left in the world!

Well, maybe that’s an exaggeration, but you get the picture. Things grew very quiet.

On subsequent, longer visits to Greece, my family and friends would come home from work for lunch around 1 p.m. or so, they would eat a big lunch, sleep for an hour or two, and then they would go back to work until about 8 p.m. in the evening.

My thinking was, why would they go back to work? You’ve already been!

Enter the siesta!

But this habit of breaking up the day and resting during the hottest hours or mid-way point is not a modern invention.

Though many ancient cultures likely took time out in the middle of the day, it was the Romans who gave it the name we are now familiar with.

The word ‘siesta’ is actually derived from the Latin word sexta, which refers to the sixth hour of daylight. This is approximately 1 p.m. in winter, and 3 p.m. in summer. If you want to know all about Roman time-keeping, you can check out the Ancient Everyday mini-series on that topic by CLICKING HERE.

In ancient Rome, the siestatime of day, the time of sexta, was actually a time to eat and rest, to gather oneself for the second half of the day, whatever that might involve, be it business in the forum, opening your shop for the evening clientele, or loading up a shipment to go to the docks in Ostia. This tradition of day-rest seems to have spread to other cultures across the Roman Empire, including Hispania where it really caught on.

People today might think that the idea of eating a big meal and then taking a long nap in the middle of the working day is ridiculous, but I wouldn’t be too hasty to judge.

There have been plenty of studies to show that midday rest, or naps, are good for productivity and physical and mental performance, they alleviate stress, and are good for the immune system, and of great benefit to cardiovascular and mental health.

Indeed some famous nappers in history were Aristotle, Leonardo da Vinci, Beethoven, Napoleon, Salvador Dali, Einstein, Winston Churchill, and Margaret Thatcher. Whether you like these people and their work or not, you can’t argue that they didn’t get a lot done or have big ideas!

The Romans were certainly a productive lot, and one has to wonder if one of the reasons they conquered so much of the world was because they knew how to take time out. Who knows? It’s possible!

Just another thing the Romans gave to the world. Perhaps it’s time we brought back the siesta in force.

Think about it…

And while you do that, I’m going to take a nap…

Thank you for reading.