Io Saturnalia, Romanophiles!

It’s that time of year again, the time which the Roman poet Catullus referred to as optimo dierum, the ‘best of days’.

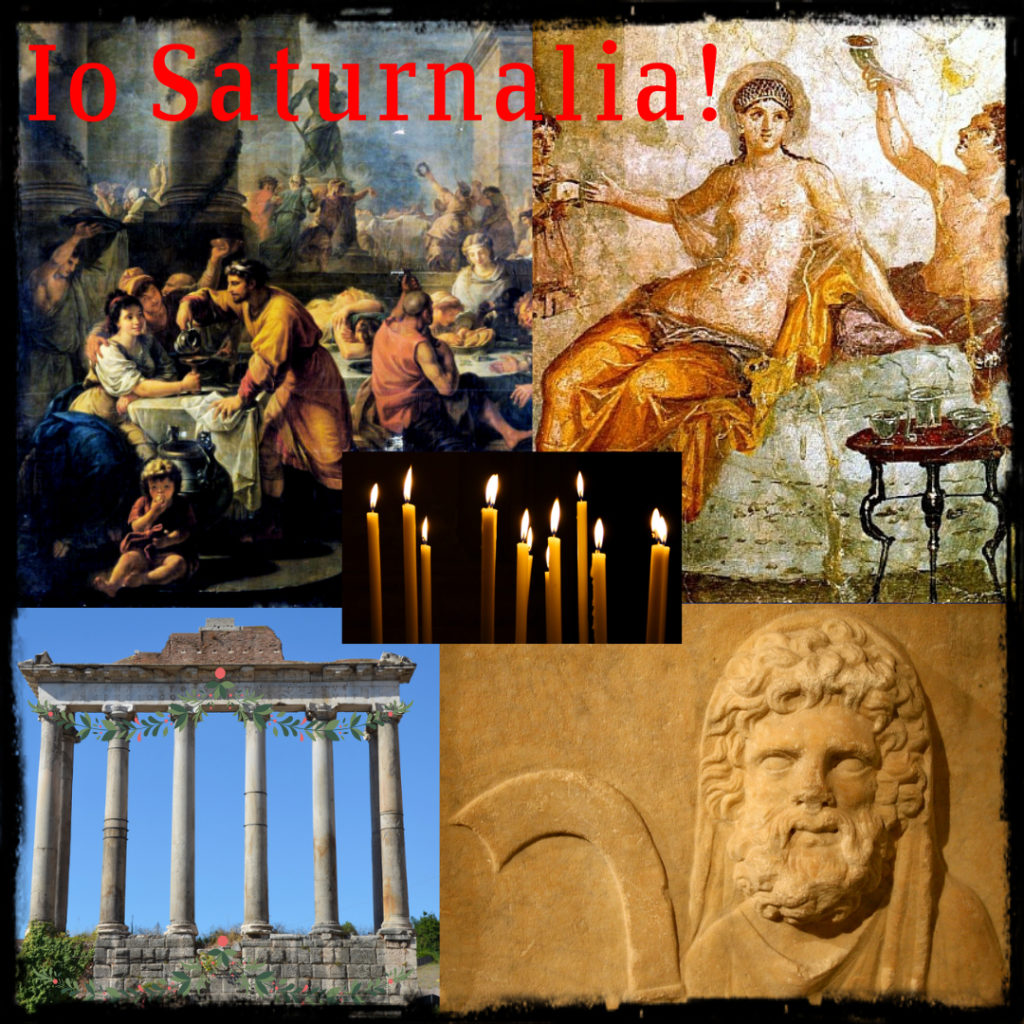

From December the 17th to the 23rd, Romans and people across the Empire would celebrate Saturn, the Winter Solstice, and the Unconquerable Sun. It can only be described as a joyous, indulgent carnival atmosphere that involved, eating, drinking, candles, holly, gifts, music, gambling, dressing up (or down!) and more. In fact many of the traditions of Saturnalia have informed our own traditions of Christmastime.

To read all about the specific traditions of Saturnalia, check out the previous post entitled Io Saturnalia! – Celebrating ‘The best of days’ in Ancient Rome by CLICKING HERE.

This year, we’re going to be looking at the festival of Saturnalia from a different angle, that is, through the eyes of ancient writers!

What did Saturnalia mean for people in ancient Rome? Was it like Christmas for us today? Did they look forward it? Did they dread the expense and preparation it required to entertain or put a smile upon the faces of their familiae?

In this brief blog post, we’re going to hear from several ancient authors about what they thought of the various aspects of this ancient and sacred festival…

The Gods Command You to Have a Good Time!

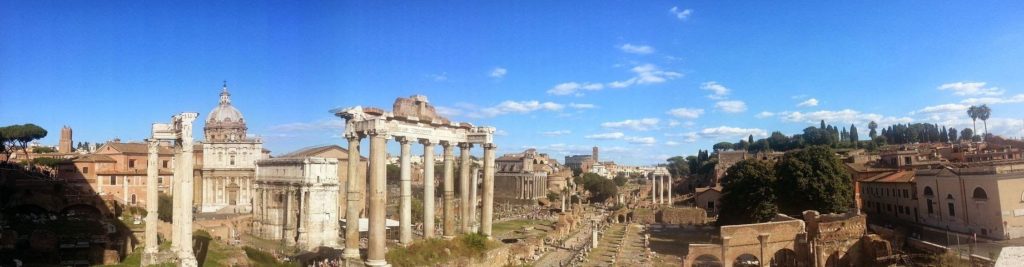

The rule of Saturnus was thought to be a mythological ‘golden age’ for Rome, and this festival harkens back to that. It honours Saturn who was the chthonic (of the earth) Roman god of seed sowing, who was often equated with the Greek god Cronus.

The Greek writer, Lucian of Samosata (c. 125-180 CE), in his dialogue, Saturnalia, relates a conversation between the god Cronus (ie. Saturn) and his priest, in which he declares that people should enjoy themselves during his festival:

Mine is a limited monarchy, you see. To begin with, it only lasts a week; that over, I am a private person, just a man in the street. Secondly, during my week the serious is barred; no business allowed. Drinking and being drunk, noise and games and dice, appointing of kings and feasting of slaves, singing naked, clapping of tremulous hands, an occasional ducking of corked faces in icy water,–such are the functions over which I preside. But the great things, wealth and gold and such, Zeus distributes as he will.

(Lucian, Saturnalia II)

This one paragraph is a wonderful source for us today because it highlights some of the most important traditions and activities of Saturnalia. and if the Gods command it, well, you HAVE to obey!

But Saturnalia was not always seven days in duration. At first, it was only a single day. As it grew in popularity, however, this expanded.

The ancient author Macrobius Theodosius Ambrosius (c. 400 CE), usually referred to simply as Macrobius, wrote what is perhaps the most famous work on this ancient festival. He acknowledges and praises the changes that led to a longer festival:

Long awaited, the seven Saturnalia are now at hand… “Our ancestors instituted many fine customs, and this is the best: from the deepest chill they produced the seven-day Saturnalia.”

(Macrobius, Saturnalia 10.3)

In addition to a lengthy period of merrymaking, just as today, things shut down for a few days. From December 17th, to December 19th, everything closed in Rome. No business was transacted and no war was waged. In a way, everyone was bound by divine decree to enjoy themselves!

Enjoy the Feast!

Just as with our own sacred days, food and eating played a major part in the Saturnalian festivities. The main sacrifice to Saturn consisted of a suckling pig, and this is what most Romans ate, if they could afford it.

The roman authorities also put on public feasts for the people of Rome, so everyone got a chance to enjoy and indulge a little. This convivium publicum was held in the Roman forum and the image of the God Saturn, presided over it.

The famous Roman historian, Titus Livius (c. 64 BCE – 12 CE), wrote about this public feast:

Finally-the month was now December – victims were slain at the temple of Saturn in Rome and a lectisternium was ordered – this time senators administered the rite – and a public feast, and throughout the City for a day and a night “Saturnalia” was cried, and the people were bidden to keep that day as a holiday and observe it in perpetuity.

(Livy, The History of Rome, Book I, XXII – 1.19)

Saturnalia was indeed a time of good will and everyone, rich and poor, master and slave, enjoyed some portion of the festivities.

A Time of Opposites

One thing that was unique to Saturnalia was the encouragement to do the opposite of what was considered normal. Rules were meant to be broken. For example, public gambling was encouraged without risk of punishment, but they did not gamble with coin, but rather, with hazelnuts! Instead of their usual toga or tunic, men wore a brightly coloured garment called a synthesis, and a pointy felt cap called a pileus. Priests at the temples and the paterfamiliae in private homes, who usually made sacrifices with their heads covered, made sacrifices during Saturnalia with their heads uncovered in the ritus Graecus, the ‘Greek fashion’.

Perhaps the most well-known, and looked-forward-to tradition for some, was the role reversal of master and slave. At one point during Saturnalia, the masters prepared and served dinner to their slaves, and gave them presents as well. Macrobius describes this for us:

Meanwhile, the head of the slave household, whose responsibility it was to offer sacrifice to the Penates, to manage the provisions and to direct the activities of the domestic servants, came to tell his master that the household had feasted according to the annual ritual custom. For at this festival, in houses that keep the proper religious usage, they first of all honour the slaves with a dinner prepared as if for the master; and only afterwards is the table set again for the head of the household. So, then, the chief slave came in to announce the time of dinner and to summon the masters to the table.

(Macrobius, Saturnalia, 1.24.22-23)

In the above quote, Macrobius references ‘houses that keep the proper religious usage’, and so, by this reference, one has to infer that there were houses where such traditions were not kept, religious or not. Surely there were houses where the slaves of the familia were treated better than in others? Those slaves whose masters observed the proper traditions of Saturnalia were, no doubt, the envy of others whose masters took a more miserly view of Saturnalia.

It does seem like most masters were happy to honour the tradition of trading places with their slaves for part of the festival, but no doubt some masters had to deal with impertinent slaves as well!

In his Satyricon, Gaius Petronius Arbiter (27-66 CE), often known simply as Petronius, refers to masters having to deal with impudent slaves during a feast, and of giving gifts to slaves:

Taking everything that was said for high praise, the foul slave now drew an earthenware lamp from his bosom, and for more than half an hour mimicked a trumpeter, while Habinnas accompanied him, squeezing his lip down with his fingers. Finally he actually stepped out into the middle of the room, and first imitated a flute player by means of broken reeds; then with riding-cloak and whip, acted the muleteer, till Habinnas called him to his side and kissed him, gave him a drink and cried, “Bravo! Massa, bravo! I’ll give you a pair of boots.”

We should never have seen the end of these tiresome inflictions but for the extra-course now coming in,- thrushes of pastry, stuffed with raisins and walnuts, followed by quinces stuck over with thorns, to represent sea-urchins. This would have been intolerable enough, had it not been for a still more outlandish dish, such a horrible concoction, we would rather have died than touch it. Directly it was on the table,- to all appearance a fatted goose, with fish and fowl of all kinds round it. “Friends,” cried Trimalchio, “every single thing you see on that dish is made out of one substance.” With my wonted perspicacity, I instantly guessed its nature, and said, giving Agamemnon a look, “For my own part, I shall be greatly surprised, if it is not all made of filth, or at any rate mud. When I was in Rome at the Saturnalia, I saw some sham eatables of the same sort.” I had not done speaking when Trimalchio explained, “As I hope to grow a bigger man,- in fortune I mean, not fat,- I declare my cook made it every bit out of a pig. Never was a more invaluable fellow! Give the word, he’ll make you a fish of the paunch, a wood-pigeon of the lard, a turtle-dove of the forehand, and a hen of the hind leg! And that’s why I very cleverly gave him such a fine and fitting name as Daedalus. And because he’s such a good servant, I brought him a present from Rome, a set of knives of Noric steel.” These he immediately ordered to be brought, and examined and admired them, even allowing us to try their edge on our cheeks.

(Petronius, Satyricon LXIX)

One imagines that a master could, when in company, be embarrassed by his slaves’ behaviour as is so hilariously portrayed by Petronius above. Though the feast of Trimalchio in Satyricon is not a Saturnalia feast, it carries many similarities, as well as a reference to the sacred festival.

But it was not only slaves who sought to call upon Saturnalia for better treatment from their masters. Cassius Dio, in The Roman History, relays how the troops in Britannia, under the command of Aulus Plautius, invoke Saturnalia when they are most upset with their commander:

While these events were happening in the city, Aulus Plautius, a senator of great renown, made a campaign against Britain; for a certain Bericus, who had been driven out of the island as a result of an uprising, had persuaded Claudius to send a force thither. Thus it came about that Plautius undertook this campaign; but he had difficulty in inducing his army to advance beyond Gaul. For the soldiers were indignant at the thought of carrying on a campaign outside the limits of the known world, and would not yield him obedience until Narcissus, who had been sent out by Claudius, mounted the tribunal of Plautius and attempted to address them. Then they became much angrier at this and would not allow Narcissus to say a word, but suddenly shouted with one accord the well-known cry, “Io Saturnalia” (for at the festival of Saturn the slaves don their masters’ dress and old festival), and at once right willingly followed Plautius…

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History LX 19)

A Time of Gift-Giving

December the 19th, the third day of Saturnalia, was the all-important day of the sigillaria. Sigillaria were gifts that were given to family members, to friends, guests, and even to slaves.

Just as today at Christmas, gifts given at Saturnalia varied widely and in accordance with one’s budget and social status. The poet Marcus Varlerius Matialis (c. 38-102 CE), known as Martial, wrote about the giving of gifts at Saturnalia:

Now, while the knights and the lordly senators delight in the festive robe, and the cap of liberty is assumed by our Jupiter; and while the slave, as he rattles the dice-box, has no fear of the Aedile, seeing that the ponds are so nearly frozen, learn alternately what is allotted to the rich and to the poor. Let each make suitable presents to his friends. That these contributions of mine are follies and trifles, and even worse, who does not know? or who denies what is so evident? But what can I do better, Saturn, on these days of pleasure, which your son himself has consecrated to you in compensation for the heaven from which he ejected you? Would you have me write of Thebes, or of Troy, or of the crimes of Mycenae? You reply, “Play with nuts. But I don’t want to waste even nuts. Reader, you may finish this book wherever you please, every subject is completed in a couple of lines.

(Martial, Epigrams XIV)

Martial seems to have especially enjoyed the gift-giving aspect of Saturnalia, for his works, Xenia, and Apophoreta, were apparently given as gifts during this ancient festival. In his Epigrams, he also gives a long list of gifts that are suitable for Saturnalia, and there is something to fit every budget.

Some of the possible gifts for guests at feasts which Martial lists include tablets (of wood or ivory); coffers (wood to hold silver, ivory to hold gold); a dice box; a gaming table; a pen case; toothpicks; ear picks; hair pins; combs; balls; hats; knives; spears; a sword and belt; a dagger; a bookcase; bundles of reed pens; candles (cerei); candlesticks; games; balls; dumbbells; leather caps; strigils; flasks; horse whips; reed pipes; slippers; pigs; various birds; vases; cups; furniture etc. etc.

Cut Out That Racket!

Not everyone enjoyed Saturnalia, however, and just as many may not look forward to the holidays today, so too did some Romans dread the advent of Saturn’s festival.

How many of us, when caught up in the chaos of entertaining and large family gatherings (before our modern plague, that is), longed for some quiet time to catch our breath? The introverts among us especially need occasion to recharge before heading back into the partying throng, no?

It was the same for the Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (c. 61-113 CE), Pliny the Younger, who relayed his need to escape the festivities:

Adjoining it is an ante-room and a chamber projected towards the sun, which the latter room catches immediately upon his rising, and retains his rays beyond mid-day though they fall aslant upon it. When I betake myself into this sitting-room, I seem to be quite away even from my villa, and I find it delightful to sit there, especially during the Saturnalia, when all the rest of the house rings with the merriment and shouts of the festival-makers; for then I do not interfere with their amusements, and they do not distract me from my studies.

(Pliny the Younger, Epistles II.17.24)

Pliny doesn’t seem to want to be a party-pooper, and so kindly withdraws to allow his guests to carry on with their revelry.

However, not everyone would have been so kind.

Enter Lucius Annaeus Seneca (c. 4-65 CE), the Scrooge of his age, it seems, for he paints a dire and distasteful picture of the Saturnalian revels going on around him:

It is the month of December, and yet the city is at this very moment in a sweat. Licence is given to the general merrymaking. Everything resounds with mighty preparations, – as if the Saturnalia differed at all from the usual business day! So true it is that the difference is nil, that I regard as correct the remark of the man who said: “Once December was a month; now it is a year.”

If I had you with me, I should be glad to consult you and find out what you think should be done, – whether we ought to make no change in our daily routine, or whether, in order not to be out of sympathy with the ways of the public, we should dine in gayer fashion and doff the toga. As it is now, we Romans have changed our dress for the sake of pleasure and holiday-making, though in former times that was only customary when the State was disturbed and had fallen on evil days. I am sure that, if I know you aright, playing the part of an umpire you would have wished that we should be neither like the liberty-capped throng in all ways, nor in all ways unlike them; unless, perhaps, this is just the season when we ought to lay down the law to the soul, and bid it be alone in refraining from pleasures just when the whole mob has let itself go in pleasures; for this is the surest proof which a man can get of his own constancy, if he neither seeks the things which are seductive and allure him to luxury, nor is led into them. It shows much more courage to remain dry and sober when the mob is drunk and vomiting; but it shows greater self-control to refuse to withdraw oneself and to do what the crowd does, but in a different way, – thus neither making oneself conspicuous nor becoming one of the crowd. For one may keep holiday without extravagance.

(Seneca, Epistles XVIII, Letters to Lucilius)

A Time of Hope

Even though some people, like Seneca, seemed to dread the coming of Saturnalia, for most it was a time of hope and celebration, a time to honour Saturn and each other, and to celebrate the Solstice and the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the birthday of the Unconquerable Sun.

It was something to look forward to at the darkest time of year.

Perhaps not that much changes? In the West, many of us look forward to December and the celebrations that do stretch on for some time.

The Greco-Roman poet, Publius Papinius Statius (c. 45-96 CE), in one of his poems, relates the feelings of hope and joy which many must have felt with the coming of December:

Mighty Apollo, and stern Pallas

And you Muses, away and play!

We’ll recall you on Janus’ Kalends.

Let unchained Saturn join with me,

And December soaked with wine,

Smiling Humour and wanton Jest,

While of happy Caesar’s joyous

Day I tell, and of tipsy feasting.

Scarce had Aurora brought the dawn,

And already good things rained down:

These the dews the easterly sprinkled:

Whichever are best of Pontic nuts,

And dates from Idume’s fertile hills,

And plums pious Damascus grows,

And figs Ebusos and Caunos ripen,

Freely the lavish spoils descend.

And pastries and ‘little Gaiuses’

Ameria’s un-dried apples and pears,

Spiced cakes and ripened dates,

Shower from an unseen palm.

Not stormy Hyas drenches Earth

Nor the Pleiades with such showers

As rattled down on the Latian theatre

Like bursts of hail from a clear sky.

Let Jupiter cloud the whole world

Threaten to deluge the open fields,

So long as our Jove brings such rain.

Look, along the aisles comes another

Crowd, handsome and finely dressed,

No less in number than those seated!

These bring bread-baskets and white

Napkins, and elegant delicacies to eat,

Those pour out mellow wine freely:

So many cupbearers down from Ida.

The fourteen rows, now virtuous, sober,

Are fed, with the people wearing gowns;

And since you nourish so many, Lord,

Annona, the price of corn’s, outweighed.

Ages, compare now, if it’s your wish,

Old Saturn’s centuries, golden days:

Never flowed wine so, even then,

Nor did harvest anticipate new year.

Every order eats here at the one table:

Women, children, knights, plebs, Senate:

Freedom has set aside reverence.

Why you yourself (which of the gods

Issues and accepts his own invitation?)

Have come to the feast along with us.

Now all, now whoever, rich or poor

Can boast of dining with our leader.

Amid the din, and rich novelties,

The pleasant spectacle flickers by.

The unskilled sex, unused to swords,

Take position in warlike combat.

They seem like troops of Amazons

In heat, by Tanais or wild Phasis.

Here’s a line of audacious midgets,

Whom Nature suddenly left off making,

And tied forever in spherical knots.

They deal wounds and ply their fists

And threaten each other with death!

Mars and blood-stained Courage laugh

While cranes swoop at their errant prey

Wondering at their pigmy pugnacity.

Now as the shades of night gather,

A scattering of riches provokes tumult!

The girls enter, now readily bought,

Here’s whatever delights the stalls,

Pleasing forms, or established skill.

Here, the fat Lydian ladies applaud,

There are cymbals, jingling Spaniards,

And there, the troops of noisy Syrians.

Here’s the theatre-mob, and those who

Barter common sulphur for broken glass.

Meanwhile vast flocks of birds suddenly

Swoop like clouds from among the stars,

Flamingos, pheasants and guinea fowl,

That Nile, Phasis and Numidia capture.

Too many to seize; the folds of gowns

Are happily filled with new-won prizes.

Countless voices, that rise to the stars,

Proclaim the Emperor’s Saturnalia,

Acclaim him leader with fond applause.

Here’s the only licence Caesar banned:

Barely had darkness cloaked the world,

When a fiery ball from the arena’s midst

Shone as it rose through the dense gloom,

Exceeding the light of the Cretan crown.

The sky was bright with flame, permitting

No licence at all to night’s dark shadows.

At the sight of it, idle Silence and Sleep

Must take themselves off to other cities.

Who could sing the free jests, the shows,

The banquets, the home-grown foodstuffs,

Those lavishly flowing rivers of wine?

Now my strength ebbs, and your liquor

Drags me tipsily towards needful slumber.

To what distant ages shall this day travel?

Sacred, undiminished, through the years.

Whilst Latium’s hills, by Father Tiber,

And Rome, still stand, and its Capitol,

That you restore to Earth: it shall remain.

(Statius, Silvae 1.6)

I do love this poem by Statius, for it seems to envelop all the religious beliefs, traditions, chaos and revelry of Saturnalia. It paints of picture of life in ancient Rome like no other.

It may not have been enjoyed by all, but it was, perhaps, the most universally celebrated festival across all classes of Romans, something to be looked forward to and shared, something to be honoured.

And with that, I say to you, dear reader, Io Saturnalia!

I hope you enjoyed this post about what ancient Romans thought of Saturnalia.

This ancient festival is a wonderful subject to research and write about, for it brings the world of ancient Rome to colourful and vivid life!

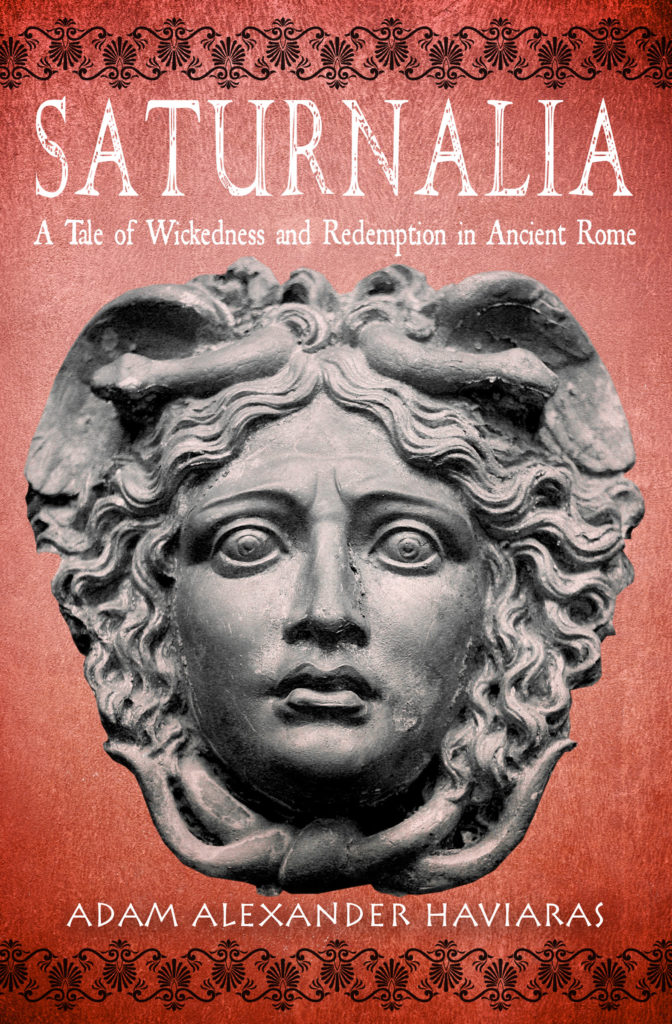

If you would like to experience ancient Rome during Saturnalia, you will want to check out Saturnalia: A Tale of Wickedness and Redemption in Ancient Rome.

Many of the sources mentioned above helped to inform the research for this book which is also a sort of homage to Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and our own holiday traditions.

You can get Saturnalia from all major bookstores and on-line retailers in e-book or paperback, from your local public library through OverDrive, as well as directly from Eagles and Dragons Publishing HERE.

For a taste of the book, see the video below in which I read an excerpt.

From all of us at Eagles and Dragons Publishing, Merry Christmas, Happy Holidays, Happy Solstice, and Io Saturnalia!