All literature, all philosophical treatises, all the voices of antiquity are full of examples for imitation, which would all lie unseen in darkness without the light of literature. (Cicero)

Salvete Romanophiles!

If you are here, presumably you like to read. Perhaps you also like to hear things read or performed? Maybe you’re a movie person? Or are comedy skits your thing?

There are many different forms of literary arts today, just as there were in ancient Rome. Actually, in Rome, no matter the literary form, there was something for everyone. You didn’t even have to be able to read to enjoy literature of a sort.

In this post, we’re going to be taking a brief look at this quite large subject by discussing the types of literature in ancient Rome, some of the main authors and surviving texts, and which forms of literature survived the test of time and public opinion in the capital the Roman Empire.

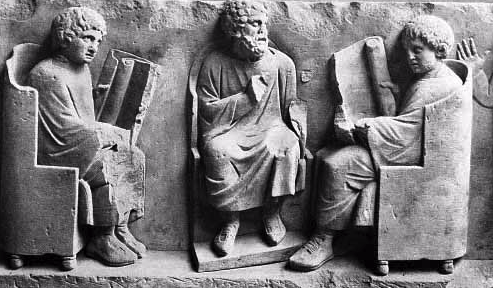

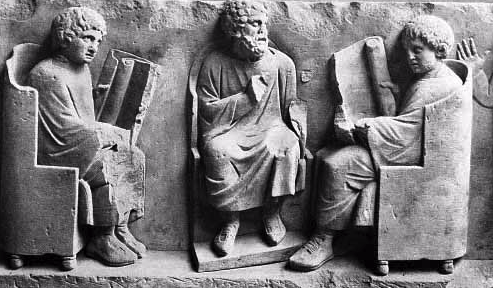

Roman writing materials

Literary sources that we know of from the world of ancient Rome include such things as histories, speeches, poems, plays, practical manuals, law books and biographies, treatises and personal letters.

More often than not, authors in ancient Rome were well-educated and even very wealthy, and as a result, the opinions often expressed in literature reflected the values of the upper classes either because the authors were of that class themselves, or because they were patronized by the wealthy.

The main types or classifications of literature were drama, poetry, prose and satire. Though much was written in each of these areas in ancient Rome, in some cases, very little has survived, which makes this a sort of tragedy in and of it self. We’re going to be taking a look at each of these in turn.

An array of Greek theatre masks

Drama was performed in Rome since before the 3rd century B.C., and these early performances took the form of mimes, dances, and farces.

One example of these early forms of drama were the fabulea atellanae which originated in the town Atella. These were a collection of vulgar farces that contained a lot of low or buffoonish comedy and rude jokes. The were often improvised by the actors who wore masks.

Mimes were very similar and were dramatic performances by men and women that were more licentious nature. They were highly popular, especially with the lower classes, but they have also been accused of being the cause of the decline of comedy in ancient Rome. By the early sixth century A.D. they were banned or suppressed.

The ancient theatre of Epidaurus, Greece

Enter SCEPARNIO, with a spade on his shoulder.

SCEPARNIO

to himself . O ye immortal Gods, what a dreadful tempest has Neptune sent us this last night! The storm has unroofed the cottage. What need of words is there? It was no storm, but what Alcmena met with in Euripides1; it has so knocked all the tiles from off the roof; more light has it given us, and has added to our windows.

Enter PLESIDIPPUS, at a distance, talking with three CITIZENS.

PLESIDIPPUS

I have both withdrawn you from your avocations, and that has not succeeded on account of which I’ve brought you; I could not catch the Procurer down at the harbour. But I have been unwilling to abandon all hope by reason of my remissness; on that account, my friends, have I the longer detained you. Now hither to the Temple of Venus am I come to see, where he was saying that he was about to perform a sacrifice.

SCEPARNIO

aloud to himself, at a distance . If I am wise, I shall be getting ready this clay that is awaiting me. Falls to work digging.

PLESIDIPPUS

looking round . Some one, I know not who, is speaking near to me. Enter DÆMONES, from his house.

DÆM.

Hallo! Sceparnio!

SCEPARNIO

Who’s calling me by name?

DÆM.

He who paid his money for you.

SCEPARNIO

turning round . As though you would say, Dæmones, that I am your slave.

DÆM.

There’s occasion for plenty of clay2, therefore dig up plenty of earth. I find that the whole of my cottage must be covered; for now it’s shining through it, more full of holes than a sieve.

PLESIDIPPUS

advancing . Health to you, good father, and to both of you, indeed. DÆM. Health to you.

SCEPARNIO

to PLESIDIPPUS, who is muffled up in a coat . But whether are you male or female, who are calling him father?

PLESIDIPPUS

Why really, I’m a man.

DÆM.

Then, man, go seek a father elsewhere. I once had an only daughter, that only one I lost. Of the male sex I never had a child.

PLESIDIPPUS

But the Gods will give—-

SCEPARNIO

going on digging . A heavy mischance to you indeed, i’ faith, whoever you are, who are occupying us, already occupied, with your prating.

PLESIDIPPUS

pointing to the cottage . Pray are you dwelling there?

SCEPARNIO

Why do you ask that? Are you reconnoitring the place for you to come and rob there?

PLESIDIPPUS

It befits a slave to be right rich in his savings, whom, in the presence of his master, the conversation cannot escape, or who is to speak rudely to a free man.

SCEPARNIO

And it befits a man to be shameless and impudent, for him to whom there’s nothing owing, of his own accord to come to the house of another person annoying people.

(Plautus, excerpt from Rudens (or ‘The Fisherman’s Rope’), Act I; Henry Thomas Riley, Ed.)

When we think of ancient theatre, however, we cannot help but think first of ancient Greek drama, which was an art form in the lands of the Hellenes long before Romans began producing Latin literature. And like so many other things, the Romans adopted forms of drama from the Greeks as well, especially drama in the form of plays.

Greek ‘New Comedy’ was introduced in Latin in Rome around 240 B.C. by Livius Andonicus and Naevius, and shortly afterward, Greek plays were being adapted by Terence, Caecilus Statius and of course, Plautus, whose early works are the oldest Latin literary works to survive in their entirety. These plays were called fabulae palliatae, or ‘plays in Greek cloaks’.

However, Latin drama had begun to evolve out of this, and soon there emerged the fabulae togatae, or ‘plays in togas’, which were comic plays about Italian life and Italian characters. Sadly, there are no surviving examples of these early Latin comedies.

Surprisingly, by the first century B.C., Roman comic plays pretty much ceased to be written and were replaced by mime which was much more vulgar and thought by many to be of little literary merit.

Illustration of Roman mime performance

Other fabulae were introduced by Livius Andronicus, including the fabula crepidata which was a Roman tragedy on a Greek theme, and the fabula praetexta which was a Roman drama based on a historical or legendary theme.

The latter, a form invented by Naevius, gained little popularity in Rome, and by the late Republican era, tragedy in general began to decline. There was a short revival under Augustus, but it did not last, and there are no surviving works of Roman tragedy that come down to us.

It seems the Romans would have leaned more toward Dumb and Dumber than Romeo and Juliet…

One theory about the lack of survival of tragedy in ancient Rome is that under the Empire, it was difficult to choose a safe subject.

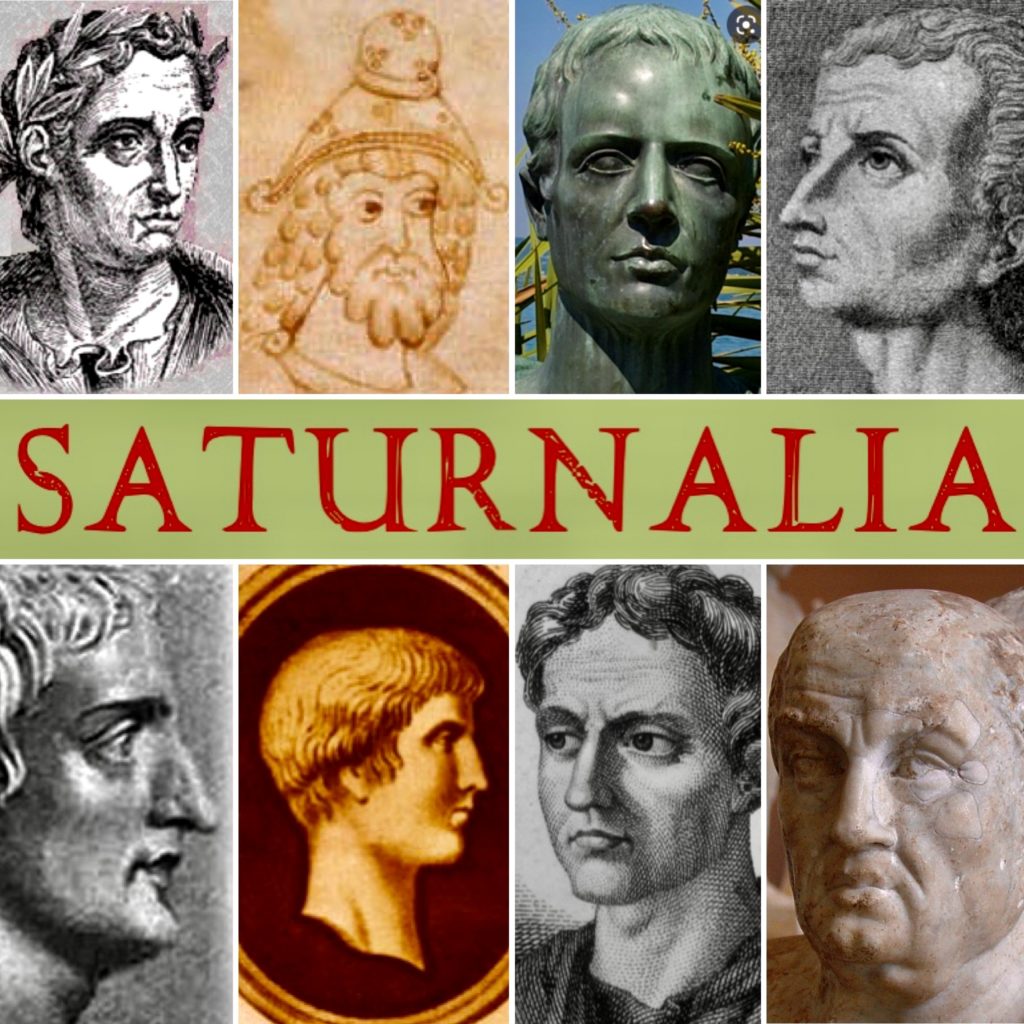

Livius Andronicus

The second form of literature we are going to look at is poetry, and this seems to have caught on much more in ancient Rome.

Again, there was some borrowing from the Greeks when it came to poetic meters, but a Latin style did develop.

The oldest form of Latin verse was known as ‘Saturnine meter’, which was named after the god Saturn, it is believed, to indicate its great antiquity.

Latin poetic verse did not have stressed or unstressed syllables like the English verse we are familiar with, but rather it relied on the larger quantity of long and short syllables in a single line.

One example of this is hexameter, which was thought to be perfected by Virgil:

Thus he cries weeping, and gives his fleet the reins, and at last glides up to the shores of Euboean Cumae. They turn the prows seaward, then with the grip of anchors’ teeth made fast the ships, and the round keels fringe the beach. In hot haste the youthful band leaps forth on the Hesperian shore; some seek the seeds of flame hidden in veins of flint, some despoil the woods, the thick coverts of game, and point to new-found streams. But loyal Aeneas seeks the heights, where Apollo sits enthroned, and a vast cavern hard by, hidden haunt of the dread Sibyl, into whom the Delian seer breathes a mighty mind and soul, revealing the future. Now they pass under the grove of Trivia and the roof of gold.

(Virgil, Aeneid, Book VI, Trans. H.R. Fairclough)

Mosaic showing Virgil with the Muses, Clio (history) and Melpomene (tragedy) – Bardo Museum, Tunis

Fescennine verses were an early form of Latin poetry that, like the mimes, were intended to amuse the masses. These were ribald in nature and took the form of songs or dialogues that were often performed at festivals. It is believed they may be the origin of Italian drama.

There were also naeniae, or neniae, were funeral poems or songs that were performed by the female relatives of the deceased, or by hired singers.

Lyric poetry was popular in ancient Rome, and was more often sung and not written. However, a very few examples of this do exist such as a poem composed by Livius Andronicus himself around 207 B.C. for the goddess Juno, and the Carmen Saeculare composed by Horace which was sung at the Secular Games of 17 B.C.

Blessed is he, who far from the cares of business,

Like one of mankind’s ancient race,

Ploughs his paternal acres, with his own bullocks,

And is free of usury’s taint,

Not roused as a soldier is, by the fierce trumpet,

Nor afraid of the angry sea,

Shunning the Forum, avoiding proud thresholds

Of citizens holding more power.

Instead he’s either out tying his full-grown vines

To the heights of his poplar trees,

Or watching his wandering herds of lowing cattle

In some secluded deep valley,

Or pruning the useless branches back with his knife,

And grafting superior ones,

Or storing thick honey away in clean vessels,

Or perhaps shearing helpless sheep:

Or when crowned with a garland of ripened fruit,

In the fields, Autumn rears its head,

How he takes delight in picking the grafted pears

And the grapes that vie with purple,

To honour Priapus, and Father Silvanus

Who’ll protect his boundaries.

It’s pleasant to lie now beneath some old oak-tree,

Or now on the springy turf,

While the streams go gliding, between their steep banks,

And little birds sing in the leaves,

And the fountains murmur, with flowing waters

That invite us to gentle sleep.

Then when Jove the Thunderer’s wintry season

Brings both rain and snow together,

With a pack of hounds you can drive fierce wild-boars,

Here and there, to waiting barriers,

Or on gleaming poles, stretch the broad-meshed nets out,

A snare for the greedy thrushes,

Or catch with a noose trembling hares, and migrating

Cranes, the most joyful of prizes.

Among such delights who can’t fail to forget,

The sad cares that passion may bring?

And if a chaste wife should be playing her part there,

In caring for home and children,

Like a Sabine girl, or the sun-tanned wife, of some

Nimble-footed Apulian,

Piling the sacred hearth high with old firewood

For her weary man’s arrival,

Penning the frisky flock in the wickerwork fold,

And draining the swollen udders,

Then pouring the year’s sweet vintage from the jar,

And preparing a home-grown meal:

Then Lucrine oysters could never delight me more

Or a dish of scar or turbot,

Should winter thundering with Eastern waves

Direct them towards our coastline:

Not African fowls, nor Ionian pheasants

Could more happily pass my lips,

Than the fruit collected from the most heavily

Loaded branches of the olive,

Or the leaves of the meadow-loving sorrel,

Mallows good for a sick body,

Or a lamb sacrificed at Terminus’ feast,

Or a kid retrieved from the wolf’s jaws.

At such a meal what a pleasure it is to see

Flocks of sheep hurrying homewards,

The listless oxen dragging along an upturned

Ploughshare, yoked to their weary necks,

And the crowd of slaves born there on a wealthy farm,

Ranged all round the gleaming Lares.’

When Alfius the usurer has uttered all this,

On the verge of a rural life,

He recalls his money, once more, on the Ides,

On the Kalends, farms it again!

(Horace, Carmen Saeculare, II, The Delights of the Country; trans. A. S. Kline)

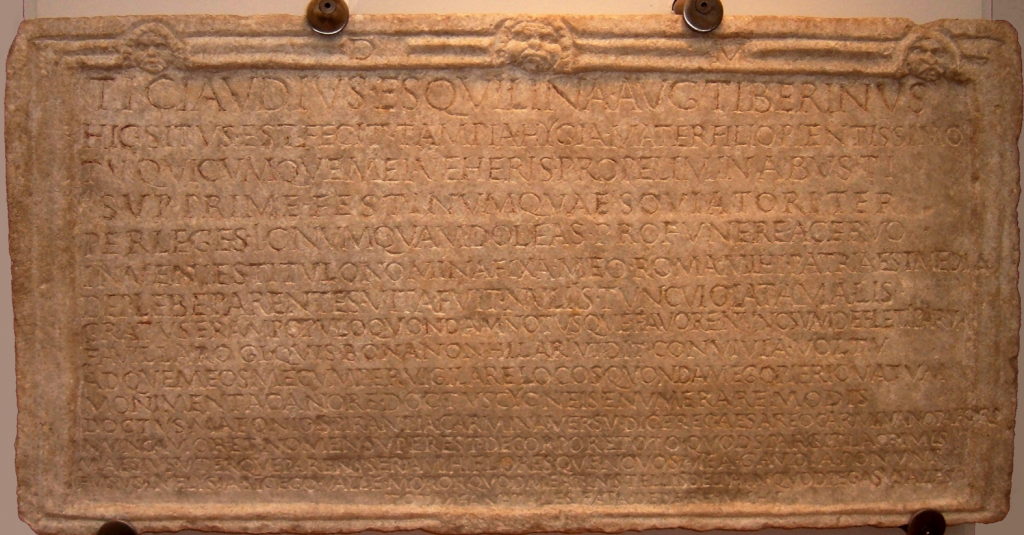

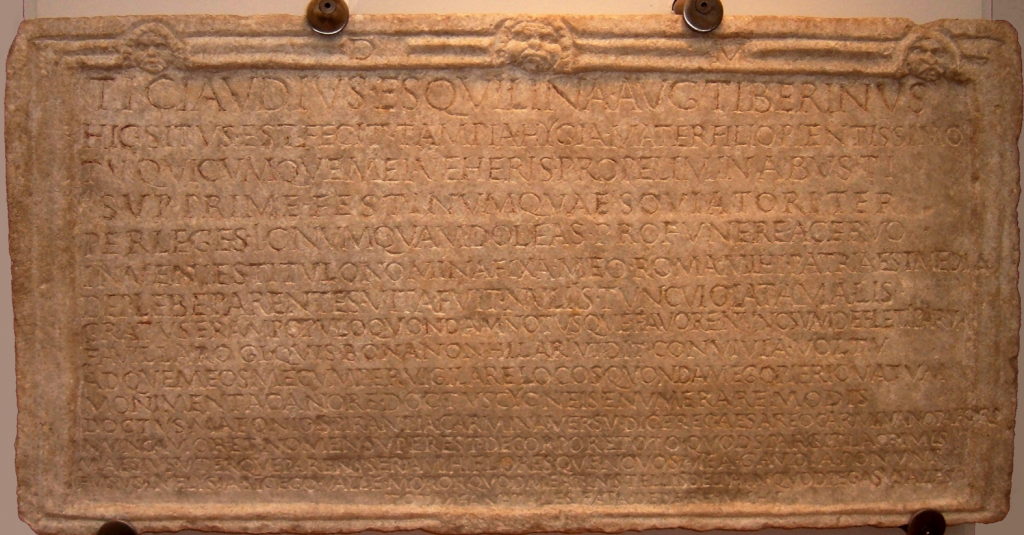

Funerary inscription for Tiberius Claudius Tiberinus

Another form of poetry that was widespread in ancient Rome was the elegy.

Elegies were poems to express personal sentiments that were commonly used in funeral inscriptions. They often took the form of an elegiac couplet with alternating lines of hexameter and pentameter.

Elegies were influenced by Greeks who were present in Rome in the first century B.C., and apart from funeral inscriptions, they were mostly used for love poetry by such writers as Gallus, Tibullus, Propertius, Catullus and Ovid.

Lesbia, come, let us live and love, and be

deaf to the vile jabber of the ugly old fools,

the sun may come up each day but when our

star is out…our night, it shall last forever and

give me a thousand kisses and a hundred more

a thousand more again, and another hundred,

another thousand, and again a hundred more,

as we kiss these passionate thousands let

us lose track; in our oblivion, we will avoid

the watchful eyes of stupid, evil peasants

hungry to figure out

how many kisses we have kissed.

(Catullus, V; trans. Michael G. Donkin)

Artist impression of Catullus singing to an audience at his villa (NYPL, Science Source Images)

Funeral inscriptions were also popular in the form of epigrams. These were written in verse, and from the second century B.C. were written on themes of love.

One of the great Roman writers of epigrams was Martial:

Laevina, so chaste as to rival even the Sabine women of old, and more austere than even her stern husband, chanced, while entrusting herself sometimes to the waters of the Lucrine lake, sometimes to those of Avernus, and while frequently refreshing herself in the baths of Baiae, to fall into flames of love, and, leaving her husband, fled with a young gallant. She arrived a Penelope, she departed a Helen.

(Martial, On Laevina, Epigram LXII; trans. Bohn.)

Pastoral landscape in Etruria

Bucolic poetry also achieved a level of popularity. This was poetry on pastoral themes, and it included such works as Virgil’s Eclogues, and Georgics, while authors such as Lucretius used this particular poetic form to give instruction, such as in his De Rerum Natura.

THE WORLD IS NOT ETERNAL

And first,

Since body of earth and water, air’s light breath,

And fiery exhalations (of which four

This sum of things is seen to be compact)

So all have birth and perishable frame,

Thus the whole nature of the world itself

Must be conceived as perishable too.

For, verily, those things of which we see

The parts and members to have birth in time

And perishable shapes, those same we mark

To be invariably born in time

And born to die. And therefore when I see

The mightiest members and the parts of this

Our world consumed and begot again,

‘Tis mine to know that also sky above

And earth beneath began of old in time

And shall in time go under to disaster.

And lest in these affairs thou deemest me

To have seized upon this point by sleight to serve

My own caprice- because I have assumed

That earth and fire are mortal things indeed,

And have not doubted water and the air

Both perish too and have affirmed the same

To be again begotten and wax big-

Mark well the argument: in first place, lo,

Some certain parts of earth, grievously parched

By unremitting suns, and trampled on

By a vast throng of feet, exhale abroad

A powdery haze and flying clouds of dust,

Which the stout winds disperse in the whole air.

A part, moreover, of her sod and soil

Is summoned to inundation by the rains;

And rivers graze and gouge the banks away.

Besides, whatever takes a part its own

In fostering and increasing [aught]…

. . . . . .

Is rendered back; and since, beyond a doubt,

Earth, the all-mother, is beheld to be

Likewise the common sepulchre of things,

Therefore thou seest her minished of her plenty,

And then again augmented with new growth.

(Lucretius, Re Rerum Natura, Book V, lines 235-260; trans. William Ellery Leonard. E. P. Dutton. 1916)

Lastly, among the poetic forms, we have epic poetry.

This was narrative poetry on a grand scale that related the deeds of ancient heroes.

It was introduced by the philhellene, Livius Andronicus, in the third century B.C. with his Latin translation of Homer’s Odyssey.

Latin epic poems were written by men such as Lucan, Silius Italicus, Valerius Flaccus, Statius and Claudian. However, when it comes to epic Latin poetry, the greatest work is by far Virgil’s Aeneid. Who can forget these opening lines?:

Arms and the man I sing, who first from the coasts of Troy, exiled by fate, came to Italy and Lavine shores; much buffeted on sea and land by violence from above, through cruel Juno’s unforgiving wrath, and much enduring in war also, till he should build a city and bring his gods to Latium; whence came the Latin race, the lords of Alba, and the lofty walls of Rome.

(Virgil, Aeneid, Book I; Trans. H.R. Fairclough)

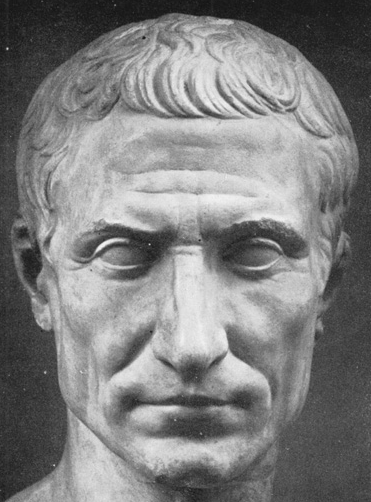

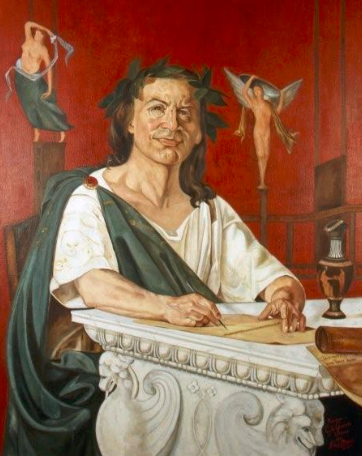

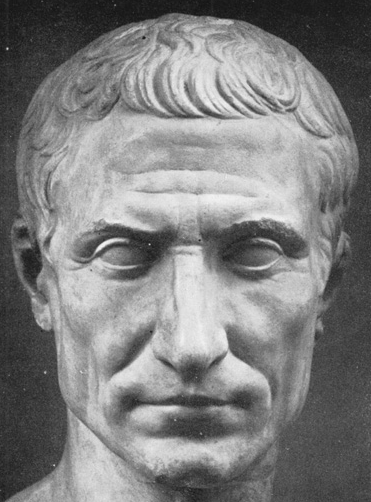

Cicero

And what of prose?

Today, prose is perhaps the most common form of literature. But in ancient Rome, though it was commonly used in certain social circles, prose was used for more than just works of fiction or non-fiction.

In ancient Rome, prose was actually born out of public speech records or annales. Interestingly, Roman prose was not really influenced by Greek tradition.

The high point of Roman prose is believed to be Cicero, the bane of every Latin student’s life.

Those, therefore, who allege that old age is devoid of useful activity adduce nothing to the purpose, and are like those who would say that the pilot does nothing in the sailing of the ship, because, while others are climbing the masts, or running about the gangways, or working at the pumps, he sits quietly in the stern and simply holds the tiller. He may not be doing what younger members of the crew are doing, but what he does is better and much more important. It is not by muscle, speed, or physical dexterity that great things are achieved, but by reflection, force of character, and judgement; in these qualities old age is usually not only not poorer, but is even richer.

(Cicero, Cato the Elder: On Old Age, XVII; ed. William Armistead Falconer)

But what were the various types of prose that one might encounter in ancient Rome?

Well, there were controversiae which were rhetorical Latin exercises in oratory that were used in the law courts.

Declamationes, were exercises that were performed by students in rhetoric, and suasoriae were speeches of advice or political oratory.

Obviously, these were forms of literature that were practiced by a select few who had the means and the will to study rhetoric, probably those who were climbing the cursus honorum.

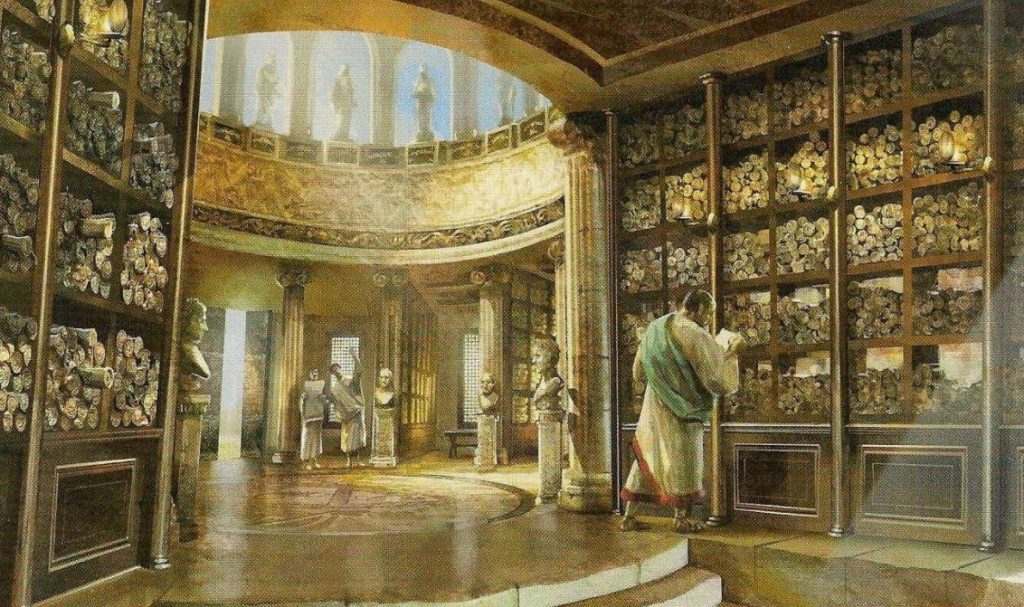

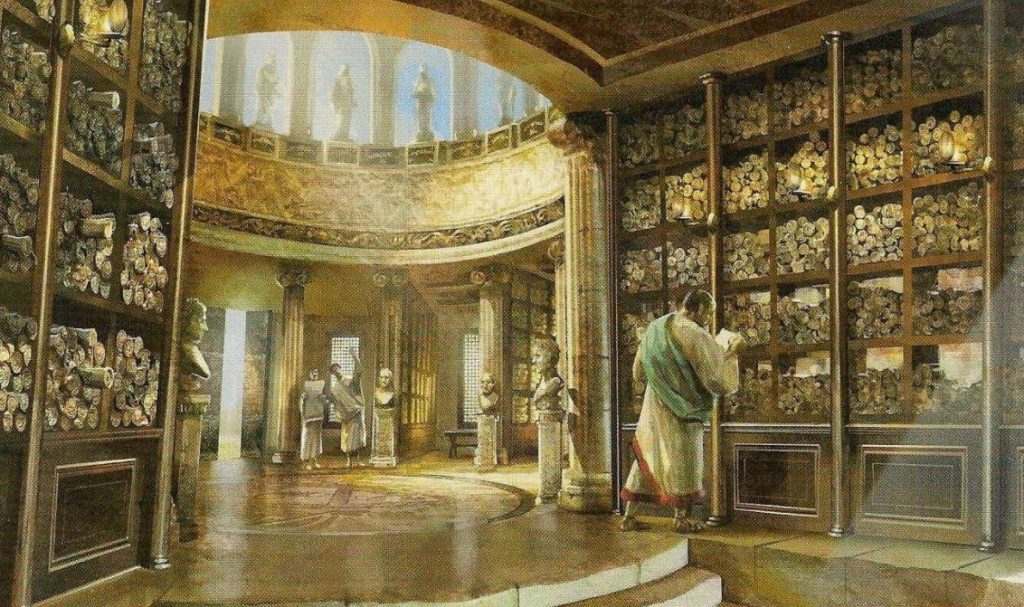

Artist impression of an ancient library

Perhaps the form of Roman prose we are most familiar with today is the ‘history’, but here there was indeed Greek influence.

The earliest Roman historians wrote in Greek because Latin had not fully developed as a literary medium, but they also wanted to tie Rome’s foundation to the glories and deeds of the more ancient Greek world. Think of of Thucydides, Aristotle, Xenophon and Herodotus to name a few. Early Roman writers wanted to live up to these great historians, or go them better.

The first historical work in Latin was Cato the Elder’s Origines which was a work on Roman and Italian history. It inspired the study of Rome’s official records which where published after 130 B.C. as the Annales Maximi. This was a history of Rome in chronological order and became a style of writing that was later used by such famous Roman authors as Sallust, Tacitus, and Ammianus Marcellinus.

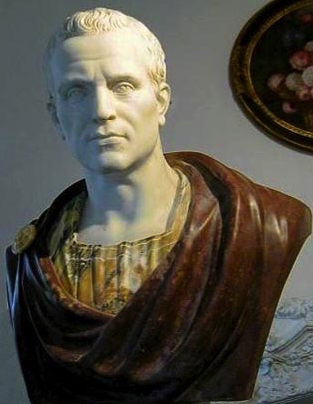

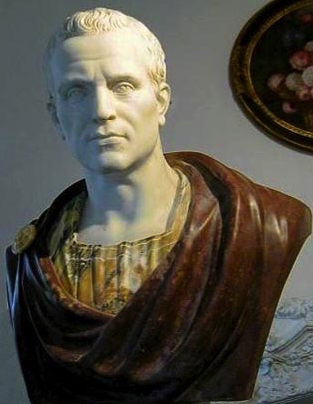

Julius Caesar

Another form of prose was the biography, and the earliest version of this was the funeral oration. Later, this developed as the memoirs of Republican generals, such as Julius Caesar’s Conquest of Gaul.

There in like manner, Vercingetorix the son of Celtillus the Arvernian, a young man of the highest power (whose father had held the supremacy of entire Gaul, and had been put to death by his fellow-citizens, for this reason, because he aimed at sovereign power), summoned together his dependents, and easily excited them. On his design being made known, they rush to arms: he is expelled from the town of Gergovia , by his uncle Gobanitio and the rest of the nobles, who were of opinion, that such an enterprise ought not to be hazarded: he did not however desist, but held in the country a levy of the needy and desperate. Having collected such a body of troops, he brings over to his sentiments such of his fellow-citizens as he has access to: he exhorts them to take up arms in behalf of the general freedom, and having assembled great forces he drives from the state his opponents, by whom he had been expelled a short time previously. He is saluted king by his partisans; he sends embassadors in every direction, he conjures them to adhere firmly to their promise. He quickly attaches to his interests the Senones , Parisii , Pictones, Cadurci, Turones , Aulerci, Lemovice, and all the others who border on the ocean; the supreme command is conferred on him by unanimous consent. On obtaining this authority, he demands hostages from all these states, he orders a fixed number of soldiers to be sent to him immediately; he determines what quantity of arms each state shall prepare at home, and before what time; he pays particular attention to the cavalry. To the utmost vigilance he adds the utmost rigor of authority; and by the severity of his punishments brings over the wavering: for on the commission of a greater crime he puts the perpetrators to death by fire and every sort of tortures; for a slighter cause, he sends home the offenders with their ears cut off, or one of their eyes put out, that they may be an example to the rest, and frighten others by the severity of their punishment.

(Julius Caesar, Caesar’s Gallic War, VII.4; Trans. W. A. McDevitte and W. S. Bohn)

No autobiographies survive from the imperial period, however, what have survived are biographies known as vitae, or ‘Lives’. There are many examples of ‘Lives’ that will be familiar to students of Roman history, including Tacitus’ life of Agricola, or the lives of the Twelve Caesars by Suetonius. Another example are the Confessiones of St. Augustine of Hippo.

Roman prose could also take the form of letters that were written for publication, such as the letters of Pliny the Younger.

Or there were the dialogues which were Greek in origin, but which Cicero used to great effect in his treatises. Dialogues were in the form of a conversation on a particular theme.

The last form of prose was one that we are perhaps more familiar with today, and that is the novel.

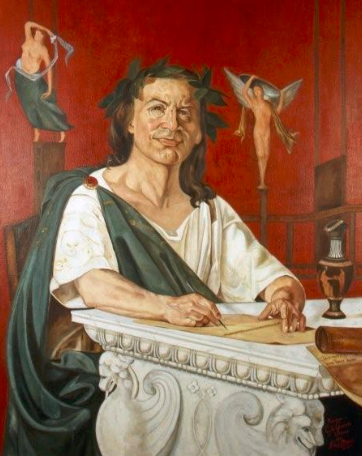

Gaius Petronius Arbiter

So after they had all wished themselves good sense and good health, Trimalchio looked at Niceros and said, “You used to be better company at a dinner; I do not know why you are dumb now, and do not utter a sound. Do please, to make me happy, tell us of your adventure.” Niceros was delighted by his friend’s amiability and said, “May I never turn another penny if I am not ready to burst with joy at seeing you in such a good humour. Well, it shall be pure fun then, though I am afraid your clever friends will laugh at me. Still, let them; I will tell my story; what harm does a man’s laugh do me? Being laughed at is more satisfactory than being sneered at.” So spake the hero, and began the following story:

“’While I was still a slave, we were living in a narrow street; the house now belongs to Gavilla. There it was God’s will that I should fall in love with the wife of Terentius the inn-keeper; you remember her, Melissa of Tarentum, a pretty round thing. But I swear it was no base passion; I did not care about her in that way, but rather because she had a beautiful nature…”

(Petronius, Satyricon, 61; trans. Michael Heseltine)

The earliest surviving novel from ancient Rome is the Satyricon which was written in a mixture of prose and some verse by Gaius Petronius Arbiter during the reign of Emperor Nero.

The only complete Latin novel to survive is Metamorphoses or The Golden Ass by Apuleius:

The moment the sun put the darkness to flight and ushered in a new

day, I woke up and arose at once. Being in any case an all too eager

student of the remarkable and miraculous, and remembering that I

was now in the heart of Thessaly, renowned the whole world over as

the cradle of magic arts and spells, and that it was in this very city

that my friend Aristomenes’ story had begun, I examined attentively

everything I saw, on tenterhooks with keen anticipation. There was

nothing I looked at in the city that I didn’t believe to be other than

what it was: I imagined that everything everywhere had been changed

by some infernal spell into a different shape – I thought the very

stones I stumbled against must be petrified human beings, I thought

the birds I heard singing and the trees growing around the city walls

had acquired their feathers and leaves in the same way, and I thought

the fountains were liquefied human bodies. I expected statues and

pictures to start walking, walls to speak, oxen and other cattle to utter

prophecies, and oracles to issue suddenly from the very sky or from

the bright sun.

(Apuleius, The Golden Ass, Book II; trans. E. J. Kenney)

When one considers how few have survived, we should probably count ourselves lucky that we have so much to choose from in the modern era.

Now we come to the final item in our short study of literature in ancient Rome: Satire.

Satire was a separate literary genre, for it could be done using various forms of literature such as dialogues, verse and prose.

In ancient Rome, satire was a personal commentary in the form of good humour or highly abusive invective. This was more popular during the Republican era, rather than the Empire for, it seems, the emperors had little sense of humour when it came to their reputations.

One of the earliest Roman satirists was Quintus Ennius who wrote satires in verse, but whose works sadly only exist in fragments now.

However, the most popular satirist in ancient Rome was Gaius Lucilius, an equestrian class author who was part of the Scipios’ inner circle during the Republican era. Sadly, very few of his works survive, and those that do are only fragmentary.

Horace (by Giacomo Di Chirico)

In researching and writing this short piece, I can’t help but be saddened by how much literature from ancient Rome has been lost to us. Yes, we have many surviving examples, but over and over I read about the work of various authors surviving only in fragments or being completely lost to us.

Did their work burn with the library of Alexandria? Were there so few copies? Was much of it memorized for performance?

The list of questions that are likely to be left unanswered is too much to contemplate.

Rather, I suppose we Romanophiles should be grateful for the works that do survive. We should study them, and try to understand them. We should enjoy them as they were meant to be enjoyed.

These surviving works of literature from a past age continue to inform us and give us a window into the people and places of the world of ancient Rome.

Thank you for reading.