We make war that we may live in peace.

Aristotle

Is this statement of Aristotle’s correct? Perhaps it was in ancient Greece when the Persians were invading the lands of the Hellenes, murdering and enslaving them. It might even have been true in the smaller world of the Greek homeland when one neighbouring city-state overstepped and boundaries for the relationship needed to be re-established.

This is a very simplistic way of looking at it. War was part of life in the ancient world and a good city-state, and its citizens, were prepared for war if the need should arise.

Perhaps the better question to ask ourselves in regard to Aristotle’s words above is this:

Is this still true today?

Do we still make war that we may live in peace? Or do we make war for other reasons? And who is the ‘We’ in all of this?

As November 11th approaches and we rightly honour the sacrifices of our men and women in uniform, past and present, on Remembrance Day and Veterans Day, questions of war are front of mind for many of us.

I’ve been thinking about writing a post like this for some time now. Let’s face it, it’s not an easy topic, and many are divided. This is more of a thought process post in which we will take a brief look at what ancient democracies and republics did when it came to the decision to go to war, and whether we can learn anything from them today.

Sadly, I can’t recall a time when there wasn’t some terrible conflict choking the screens of our televisions, or drowning the feeds of our social media platforms. Tragically, it seems that our world is at a terrible tipping point.

It seems like ‘we’ are addicted to war.

Again, I ask, who is the ‘We’ in that statement? Here is another statement from Aristotle for us to consider as we wade through the weedy terrain of this topic:

We are what we repeatedly do.

Aristotle

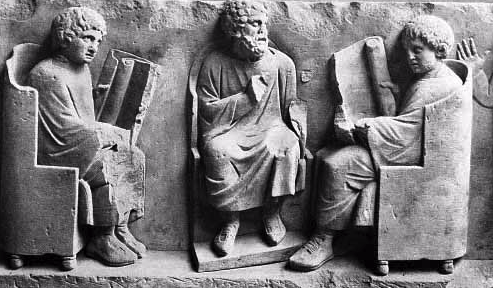

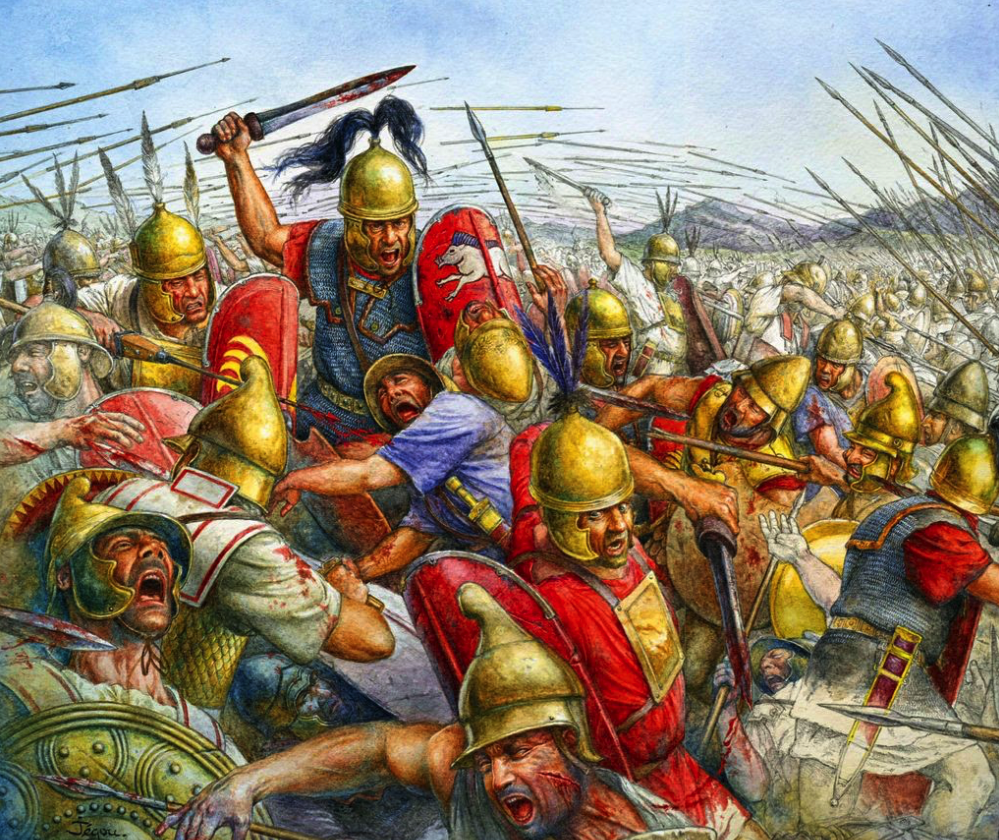

Ancient Greek Hoplites in Battle

The history of ancient democracies is marked by a fascinating interplay between citizen participation and the conduct of foreign affairs, particularly in matters of war. These early democratic societies grappled with the ethical and practical complexities of deciding whether to go to war against their enemies. The concept of “war by the people, for the people” was not only a foundational principle but also a challenging moral and strategic puzzle.

Let’s explore briefly the decision-making processes and the moral considerations that ancient democratic civilizations such as Athens and the Roman Republic confronted when deciding whether to wage war.

View of the Acropolis of Athens from the Pnyx, site of the Athenian Assembly

The Athenian Democracy

The Athenian democracy, which emerged in the 5th century BCE, is often hailed as a pioneering model of citizen participation in governance. At the heart of Athenian democracy was the Ekklesia, an assembly of free male citizens who could propose and vote on laws, including decisions related to war and peace. Thucydides, the ancient historian, captures the essence of Athenian democracy in his account of the Peloponnesian War:

Pericles… declared that a man who took no interest in public affairs was not a quiet, unoffending citizen, but a useless one. In one word, he conceived that they were born to serve the state, not only in matters great and high, but in the least and lowest also.

(Thucydides – History of the Peloponnesian War)

It is interesting to note that in ancient Greece, the word idiota referred to someone who refrained from participation in public life, who chose not to take part in the decisions that affected the democracy itself.

In ancient Athens, male citizens were expected serve the state, not only by serving the required minimum of two years in the military, but also by voting and putting forth an opinion on matters great and small, including the decision to go to war.

Are citizens’ voices and opinions held in such high regard today?

Let’s leave that particular question hanging for the moment.

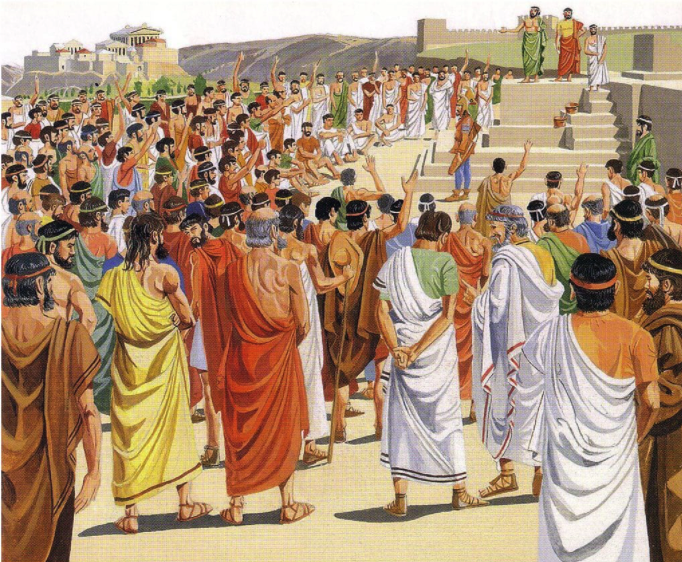

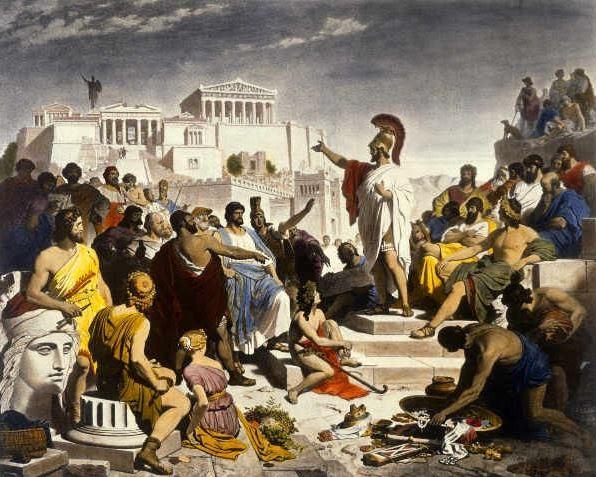

Artist impression of a meeting of the Athenian Assembly on the Pnyx

In the Ekklesia of ancient Athens, the moral dilemma of whether to undertake a certain action or policy, including whether or not to go to war, was expected to be strongly considered by the citizens of the assembly, the citizens of Athens.

However, this empowerment of citizens in the decision-making process came with its own dilemma. Athens faced a delicate balance between the pursuit of its interests and the ethical considerations of war. As Thucydides continues:

…a reason for attacking a neighbour; they thought it equitable to keep what they held and weak to give up anything, and it was more disgraceful to lose anything once possessed than not to have gained at all.

(Thucydides – History of the Peloponnesian War)

This statement will, of course, sting when it comes to the conflicts currently happening in parts of the world, as it should. However, when it comes to imperialistic tendencies, the moral dilemma behind this statement stings all the more.

If a country has what it has always had, if it has not been attacked, should it still go to war?

There is was definite tension between self-interest and moral principles in Athenian democracy. The Ekklesia had the power to decide on war, but it was not always clear whether the decision was driven by strategic necessity or imperial ambition.

Most citizens of the Greek city-states agreed that the war against Persia had to be waged. It was about survival, about ‘freedom or death’, a phrase that is ingrained in the Greek psyche to this day. Could the same be said of the Peloponnesian conflict?

Pericles’ funeral oration for Athenian dead of Peloponnesian War.

Wars have dire consequences on both sides of the conflict, so why do ‘we’ seem to be so willing to engage in them?

In ancient Athens, the people had a voice, or at least they were supposed to. Here are some specific examples of confrontations in ancient Athens in which the decision to go to war was hotly debated by the citizenry:

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) – Athens vs. Sparta

The outbreak of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta was met with significant debate in the Athenian Ekklesia. The statesman Pericles argued in favour of a defensive strategy, urging the Athenians to retreat behind the city’s walls and rely on their navy which was the strongest in the world at the time. However, there was public opposition to this strategy, with some advocating for a more aggressive stance.

Ultimately, the Athenian assembly decided to follow Pericles’ strategy, leading to the construction of the Long Walls that connected Athens to its port, Piraeus. Still, at various points during the Peloponnesian War, there were instances of public opposition to the conflict, particularly in Athens. The war’s prolonged nature and the suffering of the Athenian population led to widespread dissatisfaction.

The war, marked by several debates and shifts in strategies, eventually ended with the defeat of Athens in 404 BCE.

The Sicilian Expedition (415-413 BCE) – Athens vs. Syracuse

The Sicilian Expedition was a controversial military campaign proposed by the Athenian general Alcibiades not only against Sparta, but this time also against Corinth and Syracuse. Many Athenians were initially opposed to it due to its immense cost and risks.

Again, there was much debate in the Ekklesia of Athens with the young, arrogant Alcibiades pushing for war. In opposition to him, the commander, Nicias, debated that Athens should not go to war in Sicily, that they would be leaving powerful enemies at their backs as the war still raged in Greece. Nicias also tried to warn the assembly that Alcibiades and his proponents wanted to lead Athens into war for their own ends.

Despite public opposition and concerns, the Athenian assembly eventually approved the expedition. Unfortunately for Nicias, and for Athens, two hundred ships and thousands of soldiers were sent to Sicily, and they were all lost. Athens had spread itself too thinly and its, (and Alcibiades’) ‘imperial hubris’ were the death stroke for Athens.

The Sicilian Expedition ended in a catastrophic failure, with the Athenian fleet and forces suffering heavy losses, which significantly weakened Athens in the Peloponnesian War.

The Peloponnesian War and the Sicilian Expedition both had severe, negative impacts on both Athens and Sparta. Athens experienced a devastating plague that decimated its population, and the conflict drained its treasury. In Sparta, the prolonged war created economic hardships, and the agricultural land was ravaged. Ultimately, the war resulted in the eventual defeat and decline of Athens, but left both city-states significantly weakened.

In these prolonged conflicts one could say that both sides ‘lost’, for the winner and the loser both paid heavy prices.

Was the Athenian citizenry swayed by false promises and flowery rhetoric? Probably.

Painting depicting Cicero speaking out in the Senate

The Roman Republic

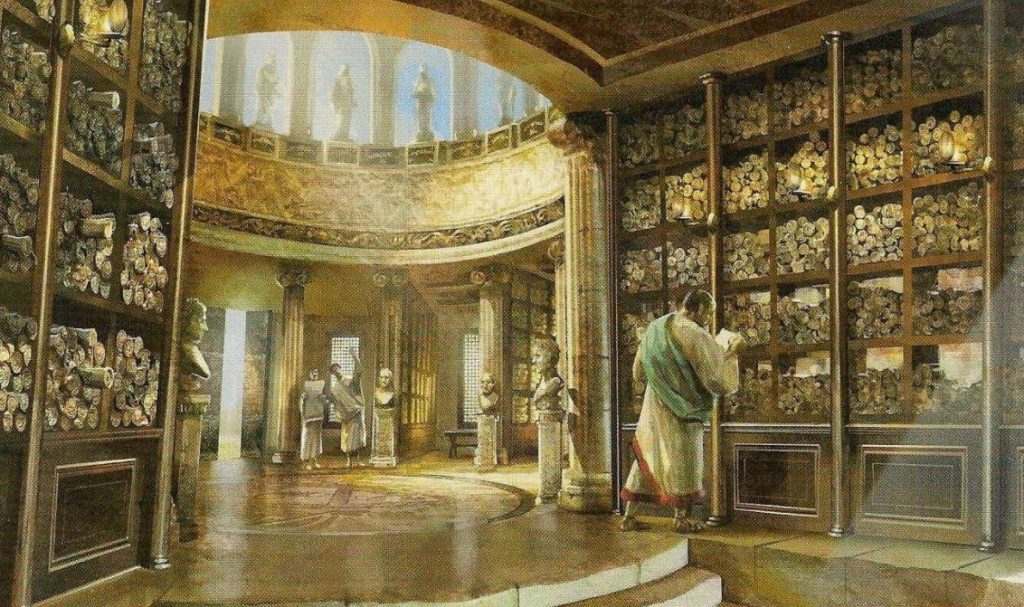

In the Roman Republic, a different form of democratic governance emerged. Power was divided between the Senate, an aristocratic body of elders, and various popular assemblies in which Roman citizens could vote on key matters. The Roman Republic’s decision to go to war was often a complex interplay between the Senate and the Popular Assemblies.

This form of government is more akin to our modern democracies than that of ancient Athens where citizens had the opportunity to speak for themselves in the assembly and to vote directly on decisions.

When it came to debates in the Roman Senate about decisions to go to war, few could argue so eloquently as the Roman statesman and philosopher, Cicero. He grappled with the ethical dimensions of war in his writings. In his work De Officiis (On Duties), he discusses the moral principles that should guide leaders in deciding whether to wage war:

[W]e must consider not only the honesty and justice of going to war, but also the ways and means of conducting it… Above all, nothing is more disgraceful than to be eager to make war, but without taking proper precautions.

(Marcus Tullius Cicero, On Duties)

Cicero’s emphasis on the necessity of just cause and proportionality in warfare reflects the moral concerns that were at the heart of Roman deliberations. He wasn’t against war, but strongly emphasized careful consideration of what it meant, the cost to the Republic and its citizens, as well as proper preparation if the decision to go to war was taken.

In the history of Rome, there were numerous wars and conflicts that were hotly debated and pushed for by various factions in the Senate and Popular Assemblies. Here are a couple of examples…

The Roman Invasion of Carthage (149-146 BCE) – Roman Republic vs. Carthage

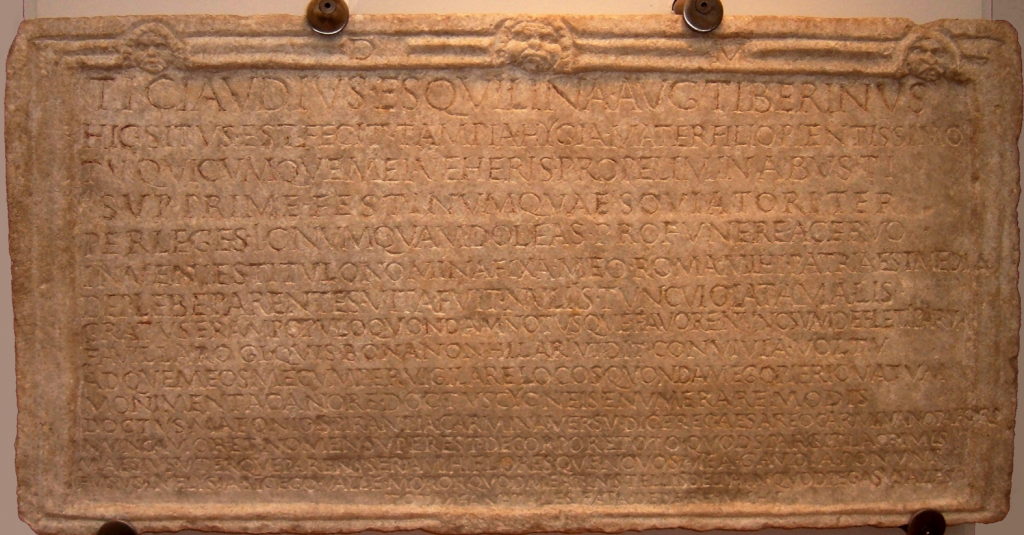

When it came to the third Punic War which followed the defeat of Hannibal in the second, the Roman Senate was divided over whether to fight Carthage once more. Prominent senators like Cato the Elder argued passionately for the destruction of Carthage, citing it as a long-term threat to Rome. He was so eager for the destruction of Carthage that it is said that he ended nearly every speech in the Senate with Carthago delenda est – “Carthage must be destroyed”.

However, others were more cautious, as Carthage posed no immediate danger, having been thoroughly trounced at the Battle of Zama.

Despite opposition to the war – for the Roman people had suffered greatly in the previous one with Hannibal arriving at the gates of Rome itself – the Roman Senate ultimately declared war on Carthage and the Third Punic War began. The conflict ended with the complete destruction of Carthage in 146 BCE, symbolized by the razing of the city, the apparent salting of the surrounding earth, and the enslavement of its population. Rome may have won that particular war, but at what cost to the Roman people?

The Roman Civil Wars (1st Century BCE) – Various Factions

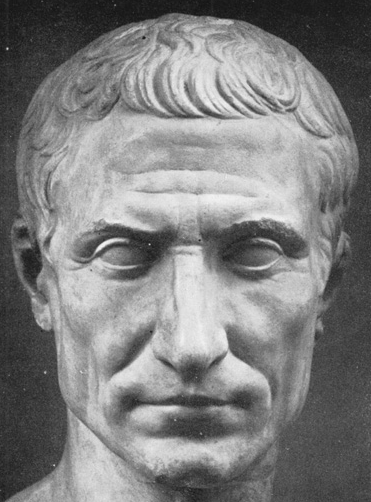

The final years of the Roman Republic were marked by intense political and military conflicts among various factions, including the Populares and the Optimates. Key figures like Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Cicero were involved in debates over the course of action. Cicero, for instance, consistently advocated for the preservation of the Republic through peaceful means. He loved the Republic, and did not want to see it destroyed.

The aim of a ship’s captain is a successful voyage; a doctor’s, health; a general’s, victory. So the aim of our ideal statesman is the citizens’ happy life–that is, a life secure in wealth, rich in resources, abundant in renown, and honourable in its moral character. That is the task which I wish him to accomplish–the greatest and best that any man can have.

(Marcus Tullius Cicero, On the Republic / On the Laws)

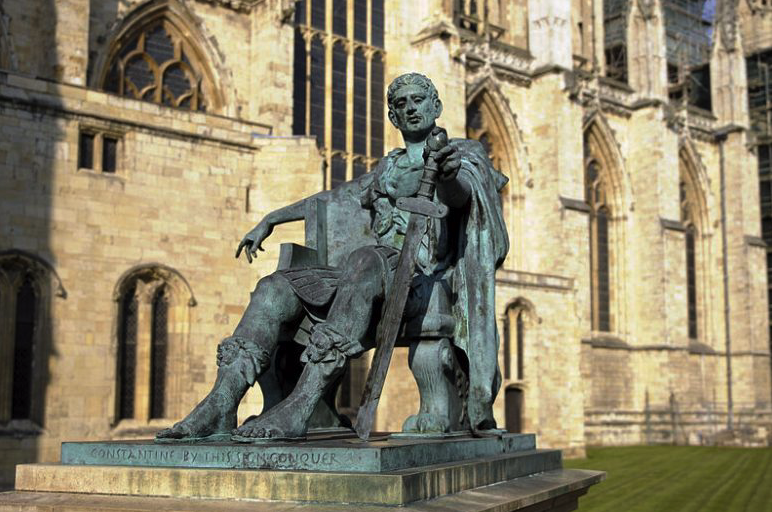

Unfortunately for the Roman people, the prolonged civil war that came out of the debates brought about political instability, economic hardships, and military conscription, which took a toll on the Roman populace. The social fabric of Rome was torn asunder, and the eventual victory of Julius Caesar marked the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire, with centralized imperial rule replacing the traditional republican system.

Cicero had been justified in his concern about the erosion of the Republic’s institutions.

In both the examples of the Third Punic War and the Civil Wars, the disregard for public opposition to war by political leaders had serious repercussions. These instances serve as cautionary tales, highlighting the consequences of leaders pursuing their agendas despite significant public resistance, ultimately leading to significant upheaval and societal change.

Civil War

This is a vastly complicated topic, and we have but scratched the surface of the armour here. We’ve only looked at a few examples out of many in the history of Greece and Rome.

Comparing the Athenian and Roman models of democracy reveals striking differences in their approaches to war. Athens embraced a more direct form of democracy, where the citizens themselves decided on matters of war. This often led to rapid and aggressive military actions. In contrast, the Roman Republic, with its complex system of checks and balances, tended to approach war with more caution, as reflected in Cicero’s moral reflections. Still, were the wishes of Rome’s citizens carefully considered? Was Cicero facing a tidal wave of opposition, or were the greedy motives of a few what brought war to the Roman people once again?

Both Athens and Rome grappled with moral considerations when deciding whether to wage war. Pericles’ assertion of civic duty in Athens and Cicero’s ethical principles in Rome demonstrate that moral discourse was intrinsic to these ancient democracies. However, both models were not infallible. One could say that the Athenian democratic and Roman Republican models allowed for debate, but were also prone to more impulsive decisions driven by self-interest.

Artist impression of the Second Macedonian War

Ancient democracies navigated the intricate path of deciding whether to wage war against their enemies. These societies, though distinct in their democratic structures, were united in their commitment to deliberating the ethical dimensions of warfare.

The tension between self-interest and moral principles was an enduring challenge, reflecting the enduring complexity of democratic decision-making.

As we reflect on these historical examples, we are reminded that the dilemma of whether to go to war or not remains a pressing concern in contemporary democracies. The lessons of the past offer valuable insights into the delicate balance between the will of the people and the moral and strategic imperatives that underpin the decision to wage war. Ancient democracies can serve as a source of inspiration and contemplation as we grapple with the challenges of our own time.

Modern politicians would do well to mind what history has taught us.

Public opposition and debates were common, reflecting the diversity of opinions within these societies. The outcomes varied, often with significant consequences for the states involved.

Certainly, there were instances in ancient Greece and Rome where the people were strongly opposed to going to war, but politicians ignored their concerns and pursued military campaigns regardless. These wars often had negative impacts on the populations involved, and this is not relegated to the distant past, but has indeed played out in the modern era.

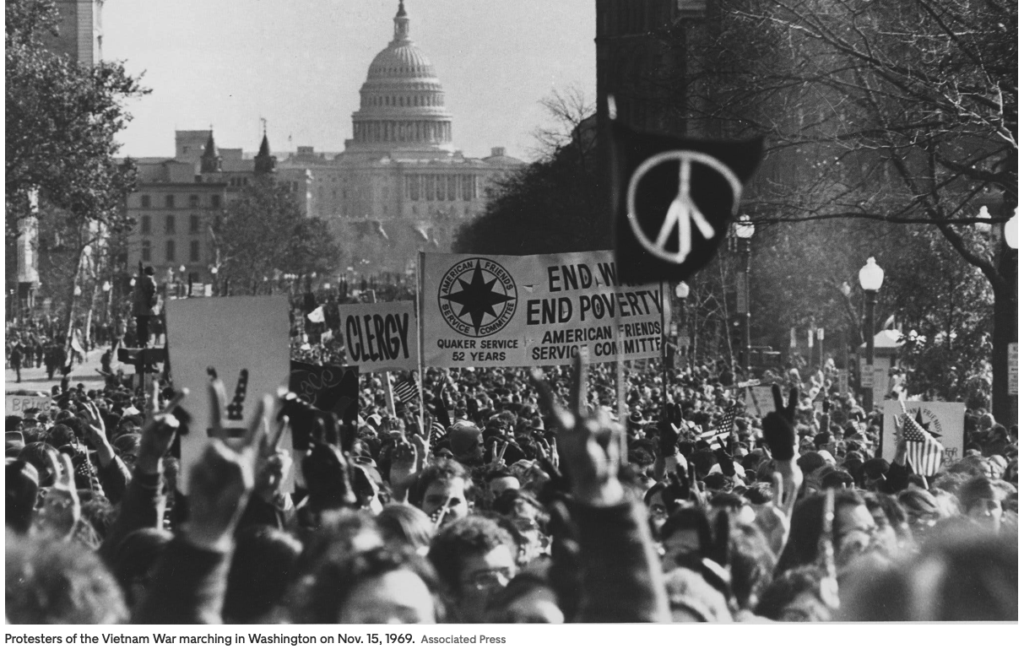

Vietnam War

Here are some examples:

The Vietnam War (1955-1975) – This conflict had devastating consequences for both the United States and Vietnam. It resulted in a high death toll, significant economic expenditure, and a deeply divided American society. The war also led to environmental damage due to the widespread use of defoliants like Agent Orange.

In the case of the Vietnam War, American politicians faced widespread public opposition, with anti-war protests, draft dodging, and disillusionment among the youth. The negative impact of the war, both in terms of lives lost and economic burden, weighed heavily on subsequent administrations. The war’s unpopularity played a role in the electoral defeat of President Lyndon B. Johnson and influenced the 1972 presidential election.

The Iraq War (2003-2011) – This war had profound negative consequences. It destabilized the region, led to the loss of thousands of lives, and incurred substantial financial costs. The war’s aftermath saw the rise of extremist groups and sectarian violence, contributing to regional instability that persists to this day.

The Iraq War faced significant public opposition, and politicians who supported it faced criticism. The war’s costs, both in terms of lives and resources, contributed to declining public support and played a role in the 2008 presidential election, where the Iraq War was a key issue.

The Afghanistan War (2001-2021) – This was America’s longest conflict, and it had significant negative consequences. It resulted in a protracted and costly military engagement, with a high human toll. Despite initial objectives to combat terrorism, Afghanistan remained politically unstable, and the Taliban regained control following the U.S. withdrawal in 2021.

The Afghanistan War eroded public support over time and, one could say, the global good will toward the U.S. after 9/11 was ultimately squandered by the drawn out conflict. Politicians who advocated for continued military involvement often faced scrutiny, and the war’s unpopularity became a factor in subsequent elections.

American troops in Afghanistan

Again, these are just a few examples of wars, but it is worth asking: Are they worth the human, financial, and societal costs?

Perhaps modern politicians should listen more closely to public opinion, and take a more ‘Ciceronian’ approach to war when assessing the costs and consequences of going to war? There should be a robust debate. Should any one person make the decision to go to war? I would say there is too much at stake to allow that.

Citizens of modern democracies are led to believe that politicians encourage open and robust debates on matters of war and conflict. Do they?

Public discourse and debate can help weigh the pros and cons, ensuring that decisions are well-informed and scrutinized. Does that happen?

Do you think that diplomacy and conflict resolution should be prioritized whenever possible?

Do you believe that war should be a last resort, and politicians should exhaust all diplomatic avenues before considering military action?

Again, we come back to one of the questions asked at the outset: Are citizens’ voices and opinions on these matters held in such high regard today as they were, say, in ancient Athens?

In ancient democracies, the people had avenues to express their wishes in matters of war, but do we truly have that today? Do the people’s wishes truly matter? Are our politicians simply taking the ‘easy’ way out?

It is more difficult to organize a peace than to win a war; but the fruits of victory will be lost if the peace is not organized.

Aristotle

The Voice of the People