The Legions are on the move once more in this second part of The World of Warriors of Epona.

In this post, we’re going to take a brief look at the site of Trimontium, which is located at Newstead.

Trimontium is the site of a Roman fort in what are today the Scottish Borders, north of Hadrian’s Wall. This was not a full legionary base, but rather a fort that housed about 1500 troops at its peak usage, cavalry in particular!

Trimontium fort site, below Eildon Hill

However, it was a major stopping point on the route north, located as it was along Dere Street, the major Roman road in the region.

I first became aware of Trimontium as part of my master’s degree thesis research while at St. Andrew’s University. In researching a theory about the activities of an historical ‘Arthur’ in the region, I came across this remarkable Roman fort set in a beautiful and dramatic setting.

A site visit was definitely in order!

If you have ever been to the Borders, you will know that the region’s pastoral beauty belies its warlike past.

Scott’s View

As I drove south from Edinburgh on the A68 (which follows the line of Roman Dere Street, bulbous green and treeless landscapes gave way to fertile fields lined with hedges and accented with summer wildflowers. It was a bright, sunny day, which was often not the case in Scotland, and so I could see for some distance.

As we approached the River Tweed, the three peaks of the Eildon Hills came into view with the river sparkling in the summer sun. I was finally there, having followed in the footsteps of the legions.

Trimontium from the A68 with Tweed river and bridge

This area is loaded with wonderful places to see such as Scott’s view, a favourite place of reflection for Sir Walter Scott and a great spot from which to see the Eildon Hills, Dryburgh Abbey, Melrose Abbey (where the heart of Robert the Bruce’s heart is buried), and myriad country paths.

But it was the Roman presence that concerned me on this trip.

Eildon Hill from the ruins of Melrose Abbey

The fort at Trimontium was used as a marching camp by Agricola’s troops c. A.D. 80 and had eight subsequent phases of Roman occupation all the way to the time of Septimius Severus’ campaigns into Caledonia in the early 3rd century, the latter being the time in which Warriors of Epona takes place.

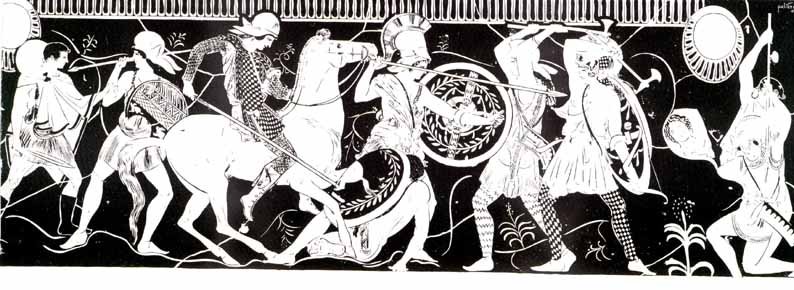

Trimontium is so-named because of the three peaks of the Eildon Hills that overshadow it. It was on the marching route to the north and provided a visible and central meeting place for the legions and auxiliaries. Some of the most important finds to come from the area are the horse harness and ornamental cavalry armour of the troops that were stationed there.

2nd century Roman cavalry auxiliaries (illustrated by Kawaleria Rzymska)

These finds are wonderful and some can be seen in the museum in Melrose, but mainly in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. The cavalry masks discovered at Trimontium inspired some tweaks to Lucius Metellus Anguis’ own armour in the book.

The Newstead Cavalry Mask (wikimedia commons)

It was the obvious presence of Roman auxiliary cavalry that gripped my imagination then, and so it quickly became obvious that Lucius and his Sarmatian cavalry ala would be based at Trimontium during a portion of Severus’ Caledonian campaign, the final phase of use for Trimontium.

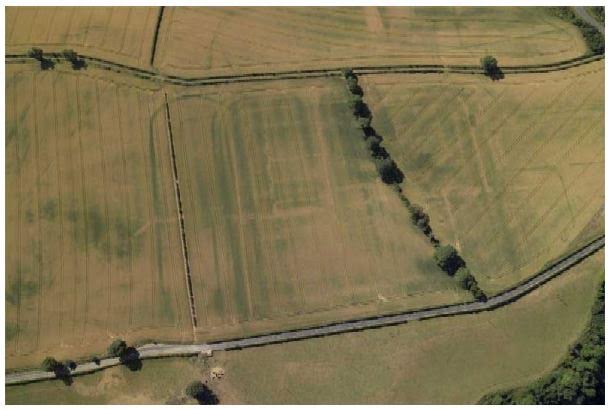

Crop marks showing outline of fort at Newstead

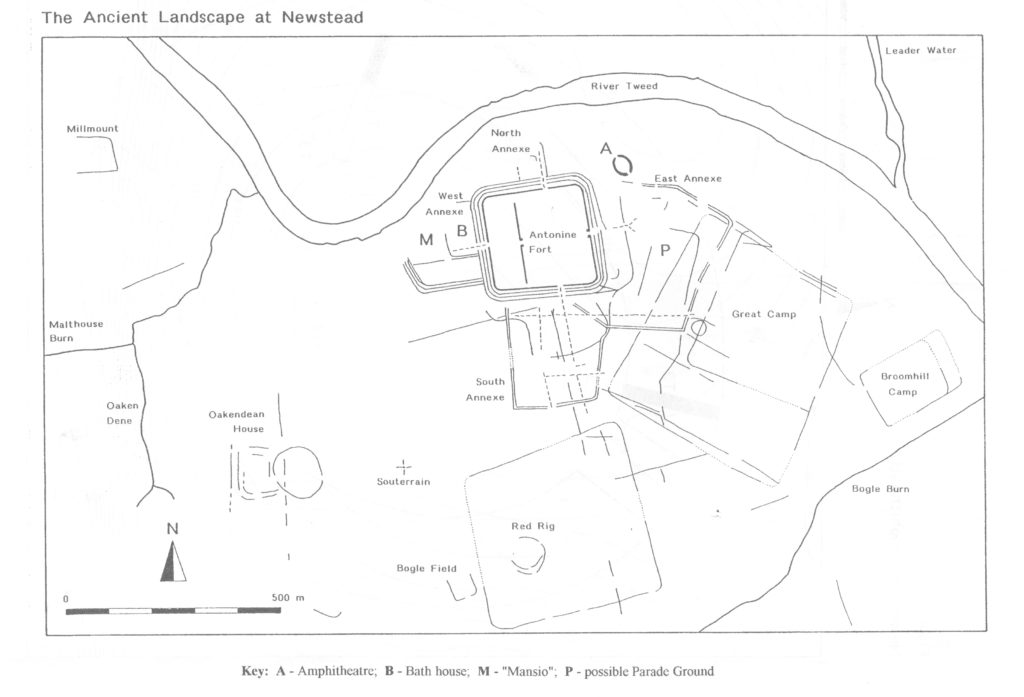

Though today almost nothing remains of the Roman fort (it’s mainly a great field), during the Antonine period, the fort at Trimontium had three defensive ditches and a rampart, a principia (headquarters building) that may also have served as an exercise hall just off of the via Decumana, barracks, stables, a commander’s house, and granaries.

There were also annexes on every side of the fort with a parade ground on the east side, and a mansio (a sort of hostel) and bath house on the west side.

Plan of the site and successive fort(s) at Trimontium (from Newstead 1996 – The Northern Vicus and the Amphitheatre Excavations and Survey; University of Bradford)

Trimontium did not only have a military presence. Wherever the Roman army went, there were others who followed – wives and children, merchants, prostitutes and others.

Outside the walls of the fort, as with many Roman forts, there was a vicus, a civilian settlement on the north side where the people mentioned above would have lived.

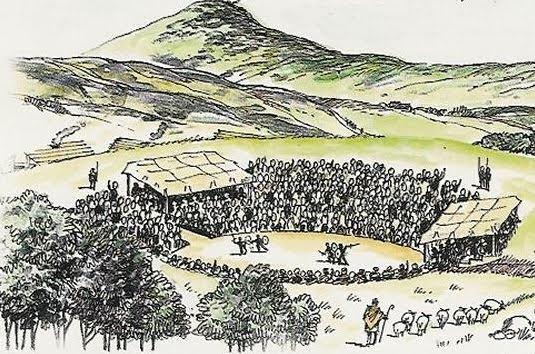

But one of the most interesting features of Trimontium’s fort is the presence of an amphitheatre beyond the north-east corner of the fortress, near the banks of the River Tweed. The outlines indicate that it was elliptical rather than round, and because of its location next to the military installation, it was likely used not only for games, but also for drills.

Artist impression of Newstead Amphitheatre

When you visit a site like the fort of Trimontium, there actually isn’t much to see when you are ‘on the ground’. It helps to do a bit of research beforehand so you know what you are looking at.

For someone like me, who is interested not only in the site, but the smell of the air, the sound of the wind and the view of the surroundings, it is magic for my creativity. But it also helps to get a bird’s eye view of the site.

If you don’t have a helicopter or bi-plane, the best way to do that is to climb Eildon Hill North, the biggest, broadest peak of the three and that which overlooks Melrose and the fort at Trimontium.

Eildon Hill North (Wikimedia Commons)

I drove the car as close as I could get to the base of the hill, having left the fort behind, parked, and began to climb.

From a distance, Eildon Hill North doesn’t seem so big, but when you get up close, you realized you have quite a workout ahead of you. I was glad of my hiking boots, let me tell you.

Once at the top, the world opens up before you. The view is magnificent.

But after the calm beauty of the farmlands down around the fort, the howling winds at the top of Eildon Hill North made for quite a contrast. It wasn’t a place to picnic when I finally got up there.

View from the top of Eildon Hill