Hello fellow history-lovers!

Welcome back to the blog for another exciting announcement. Over the past two weeks, we’ve introduced you to Eagles and Dragons Publishing’s new non-fiction series, HISTORIA, and the first two volumes having to do with Celtic Literary Archetypes and Arthurian Romance.

This week, we want to introduce you to the third volume in the series:

Y Gododdin– The Last Stand of Three Hundred Britons: Understanding People and Events during Britain’s Heroic Age

This book introduces the reader to one of the most important and moving literary works to come out of Dark Age Britain: The Gododdin of Aneirin.

The Gododdin is not only a praise poem and elegy for three hundred British warriors who made a heroic last stand against the invaders of their island, it is also an important source for understanding the culture, people, and events of the seventh century.

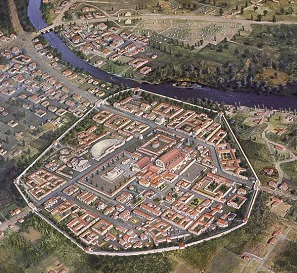

In this book, the reader will learn about the poem itself, the historical background, as well as the archaeological evidence that has come to light.

The Gododdin is an inspiring, tragic tribute to ‘three hundred gold-torqued warriors’, composed by a man who was their contemporary and friend who sought to ensure their sacrifice would never be forgotten.

If you are studying The Gododdin itself, or have an interest in Celtic, Arthurian, or Dark Age studies, then you will enjoy this short study of the heroic last stand of three hundred men against thousands, an act of historical bravery worthy of the successors of Arthur himself.

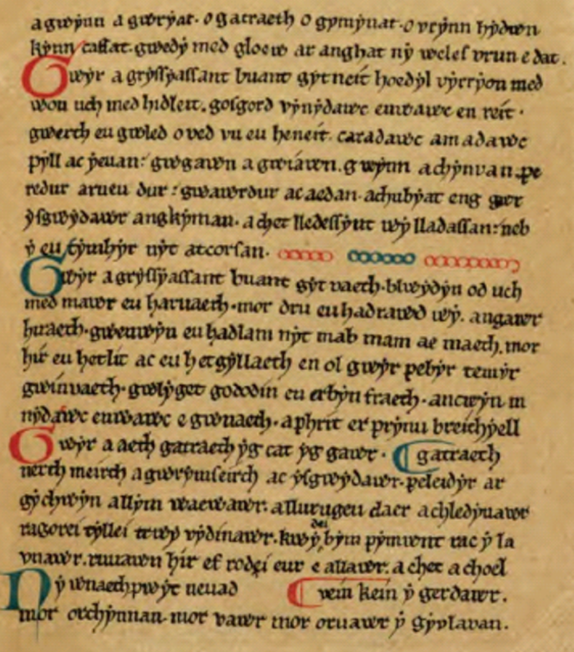

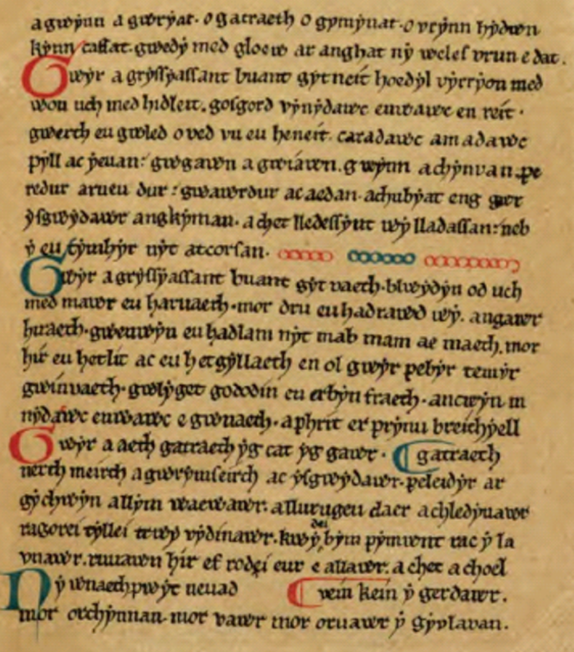

Page from the Book of Aneirin – NLW Llyfr Aneirin, Cardiff MS 2.81 (Wikimedia Commons)

The poem, Y Gododdin, is perhaps one that not many of you have heard of before, unless you’ve studied early medieval Welsh poetry, Celtic or Arthurian studies.

I actually came across the poem during my graduate studies, as well as part of my research into the historical ‘Arthur’. The mention of ‘Arthur’ is what drew me to the poem in the first place, but Y Gododdin is so much more than that small reference to a Romano-British hero.

Aneirin’s poem is an amazing example of bardic praise poetry. It sounds very different read aloud, versus in one’s head. But it’s also a moving tribute, an elegy, to a group of three hundred warriors who knew, more or less, that they were riding to their deaths.

I compare the ride of the Gododdin warriors to the last stand of the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, and I don’t believe this is an exaggeration. The poem sings of their deeds and bravery, but it also gives us an insight into Dark Age society that is invaluable to our understanding of the age.

To me, Y Gododdin is a sort of ‘swan song’ for Romano-Celtic Britain.

If you are interested in getting a copy of this third book in the HISTORIA non-fiction series, you can check it out on Amazon, iTunes and Kobo by CLICKING HERE.

You can also purchase a copy directly from Eagles and Dragons Publishing on the ‘Buy Direct from Eagles and Dragons’ tab of the website, or by CLICKING HERE.

That concludes our launch series for HISTORIA, but we will continue to add more titles over time with the fourth volume coming sometime in the autumn.

Thank you for reading!