Greetings readers and history-lovers!

It’s been a brilliant summer, but after some time off, new adventures, and a lot more writing, we’re back on with the blog.

It’s going to be a busy fall this year with some very exciting announcements coming up soon, so if you are not a mailing list subscriber, you should sign-up now so you don’t miss anything.

If you were following along on the Instagram feed, you’ll know that I was in Greece visiting with family for about five scorching weeks.

Normally, when we go back to Greece, we visit many archaeological sites, but this time, it was more about family and refilling the creative well. Besides, the days were so hot that it was bordering on dangerous. I can still feel the burning, crisping sensation on my arms!

Pegasus constellation as seen through ‘Star Walk’ app

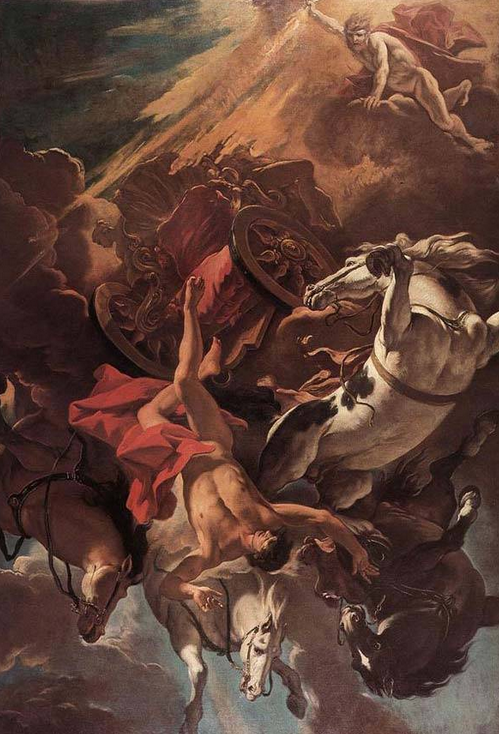

It was wonderful to hear and see that symphony of Greek summer – the gentle lap of water on pebbled beaches, brilliant sunrises that roused the chorus of cicadas, wine-filled sunsets watching the chariot of the sun disappear into the West, and night skies filled with legendary constellations – every day it was different and awe-inspiring.

I especially enjoyed the sweet scent of pine and wild thyme in the heat of day as I stared out the sky and sea, a world in myriad shades of blue…

But the historian in me would think it blasphemous to be in Greece and not visit at least one archaeological site. And so, after my seaside idyll in the Argolid peninsula, during my last couple of days in Athens, I made my way to the heart of the city to a site I had not visited in some years – the ancient agora of Athens.

Before I tell you what it felt like to return to this ancient place, here is a bit of history for those of you who are not familiar with it.

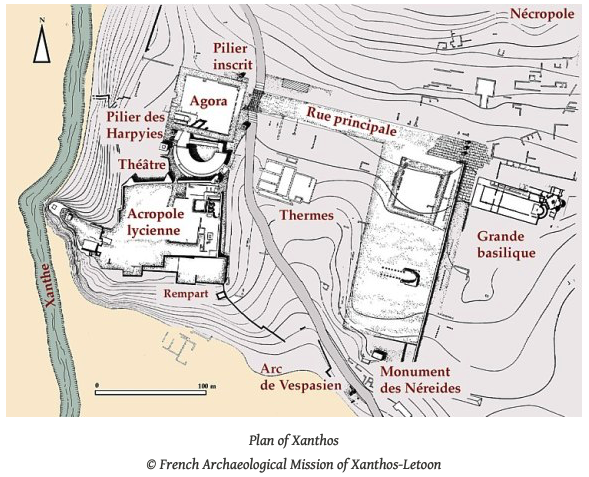

The agora has been the beating heart of ancient Athens since at least the sixth century B.C. I don’t mean human activity, for that goes march farther back. I mean that the agora has been the social, commercial, entertainment, political and religious heart of Athens since then.

Almost everything of import in Athens’ history happened in and around the agora, including the birth of Democracy.

The Agora of ancient Athens with the Acropolis in the background

The area of the agora is actually known as ‘Thiseio’. Years ago, when I first visited the agora, I asked about this and discovered that this stems from the mistaken belief that the intact temple of Hephaestus overlooking the site was a temple dedicated to Theseus, the legendary king of Athens (yes, Theseus who escaped the labyrinth!).

As part of the Theseus connection, there is a legend (mentioned by Pausanias) that a great battle took place on the site of the agora between the Greeks and invading Amazons who had been angered that Antiope, the sister of Queen Hippolyta and Penthesilea, fell in love with the Athenian king and returned there with him.

Antiope was killed during the battle, but Theseus and the Greeks were victorious nonetheless. As an aside, this tragic tale is depicted in a brilliant novel by Steven Pressfield, Last of the Amazons.

Statue of Theseus at Thisieo metro station in Athens

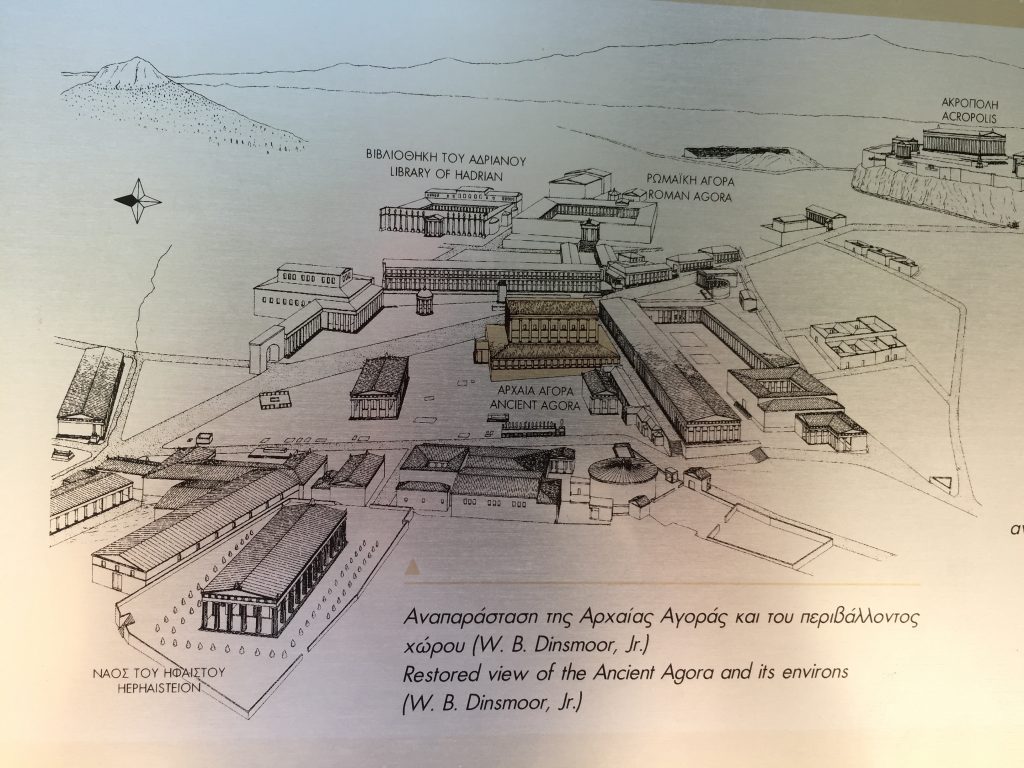

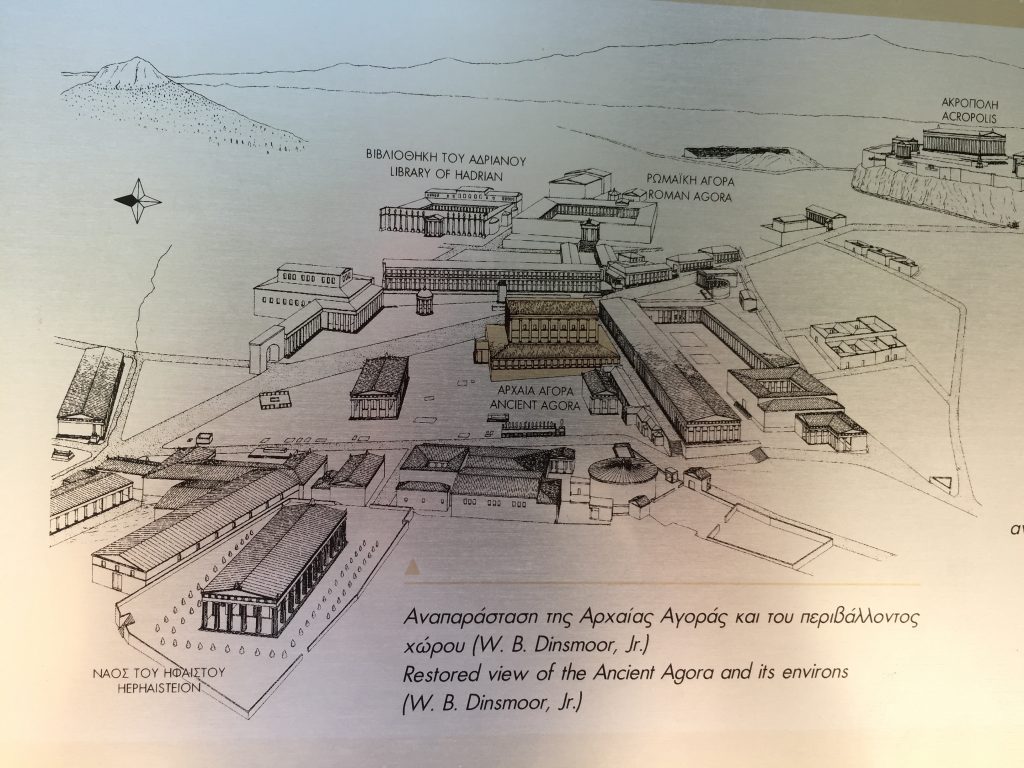

The ancient agora lies in the shadow of the Acropolis of Athens with the Areopagus (Ares’ Rock), Athens’ oldest court, to the southwest. Fun Fact: the Areopagus is called that because that is where the Gods tried Ares for murder. Murder trials continued to take place there during Athens’ history.

The agora is also flanked by the hill of Kolonos Agoraios, dominated by the temple of Hephaestus to the west, and the reconstructed stoa of Attalos to the east.

The Panathenaic Way, the road that ran from the great Dipylon Gate of Athens to the Acropolis, ran directly through the agora, as did the road to the ancient port of Piraeus.

The archaeological site is packed with ruins. In fact, excavations under the Archaeological Society and the American School of Classical Studies have been ongoing here since 1931.

Map of ancient Agora of Athens

The ancient agora of Athens is a place of many layers, and it’s no wonder, for it was destroyed several times in its history. The Persians destroyed it during their invasion of 480 B.C., and the Romans under Sulla did their dirty work in 86 B.C.

Later, in A.D. 267, the Herulians (a Scythian people from around the Black Sea) sacked Athens, and then the Slavs did the same in A.D. 580, not to mention the damage that was done during the wars of independence and other conflicts.

The stones of the ancient agora had born witness to a lot before being buried beneath the modern neighbourhood of ‘Vrysaki’.

I’m not going to go into every single monument that is visible today in the agora. There arsenal of ancient Athens, various stoas, the altar of Zeus Agoraios, the altar of the twelve gods, the temple of Ares, the Odeion of Agrippa, the library, and the temple of Apollo Patroos are just a few of the ruins you can wander around.

Like many archaeological sites in Greece for me, a visit to the ancient agora of Athens is something more to be felt.

After taking the subway to Monastiraki station in the heart of the flea market and Plaka tourist district, we made our way through the thick and sweaty crowds, along tavernas with misting fans to the entrance on the northern side of the agora.

It seems all the world still comes to the agora of Athens. I counted about nine different languages alone in the line to get in. After a few minutes, we had our tickets and walked through to a spot away from the milling masses of snap-happy tour groups to look up and see the shining beacon of the Acropolis and the creamy white structures of the Erechtheum, Propylaea, and the Parthenon. It always fills me with silent awe to look up at that view, and the Agora is one of the best places to admire it.

View of Acropolis from centre of Agora

To the far left, the Stoa of Attalos, where the museum is located, beckoned with its long shaded colonnades of cool marble, but we would leave that until last. Glancing up to my right, the sentry temple of Hephaestus upon the hill called to me, and so I began to make my way.

Thankfully, trees abound in the agora, so you can take your time and admire all there is to see from frequent pockets of shade brimming with cicada song.

I passed the site of the altar of the twelve gods and the overgrown ruins of the temple of Ares, unnoticed by most tourists, to stand before the imposing ruins of the Roman-build Odeion of Agrippa built in 15 B.C., and destroyed during the later Herulian attack. This spot is at the centre of the agora, and I stood there for a few minutes, gazing out from beneath the imposing statues of Tritons.

One of the Tritons on the facade of the Roman Odeion of Agrippa

After a time pretending the murmur of tourists was the sound of ancient Athenians, I continued my walk to the altar of Zeus Agoraios, one of my favourite spots in the agora. How many offerings had been made there to the King of the Gods? The altar’s base is quite intact, and it stands in stony silence with the expanse of the agora before it, and the temple of Hephaestus and the ancient arsenal on the hill behind.

After watching most tourist by-pass Zeus’ altar as if it were just another pile of rocks, I turned around and looked up at the temple of Hephaestus, one of the most intact ancient temples I have ever seen.

Looking toward the temple of Hephaestus from the altar of Zeus

The climb up is not long, but in that heat, I passed pockets of visitors resting in the shade of trees on their way up.

I couldn’t wait, however, and pressed on along the narrow, rocky path to the top.

There is something about the design of an ancient temple that appeals to my senses. I don’t know what it is. Perhaps is it is the simple lines that give one a sense of peace and order, or the ancient belief that it was where one communed with that particular god? Maybe there is something to the golden mean that permeates every aspect of those ancient structures?

I don’t know for certain, but when I am in the presence of such a beautiful structure, I fall silent. The fact that that temple is so intact makes it even more powerful.

Looking at the interior of the temple of Hephaestus

I strolled around the perimeter of the temple, admiring the strength of its doric columns. When I reached the back, I stood peering inside, catching a glimpse of the ancient cella at its heart, so dark and quiet, cool in the middle of the inferno outside.

I had been to visit the temple before, years ago, but every time is like a first time in places like that. Our experiences change us between visits over the years. We notice new things, feel differently when we return, even though the sites themselves are frozen in time.

After admiring the temple, it was time to make our way back across the southern end of the agora toward the reconstructed stoa of Attalos. This route takes you back through the heart of the agora, along the length of the ruins of the middle stoa where you can see the rooms from which the ancient city was administered.

If you look up, you can see the Acropolis with even greater clarity, and the masses of tourists wending their way up like a flow of busy ants around a hill.

As I walked, there was much more to see, but the heat was intensifying. Some things would have to wait until the next visit.

The colonnade of the restored Stoa of Attalos

The stoa of Attalos, built in the second century B.C. by that King of Pergamon (159-138 B.C.), was busy with people taking refuge from the shade, talking, resting, shopping in the museum shop, and admiring the remnants of Athens’ great past. You could hear tour guides teaching their groups about this history of Athens, Greek visitors talking politics, and others taking in the view and discussing the next part of their journey in Greece. The scene, apart from the clothing and languages spoken, might not have been that different from two thousand years before.

As for me, I made my way into the small museum that is housed on the ground floor of the stoa. Don’t let the size of this museum fool you. It houses a wonderful collection of artifacts from the full range of Athenian history in the agora from early Bronze Age tombs, through the Geometric period, the Classical period, and into the Hellenistic and Roman ages.

One of my favourite pieces was a three-handled bowl of which I had recently bought a wonderful replica from our friends at the Ceramotechnica Xipolias in ancient Epidaurus.

Here are a few of the wonderful artifacts that are in the museum of the ancient Agora:

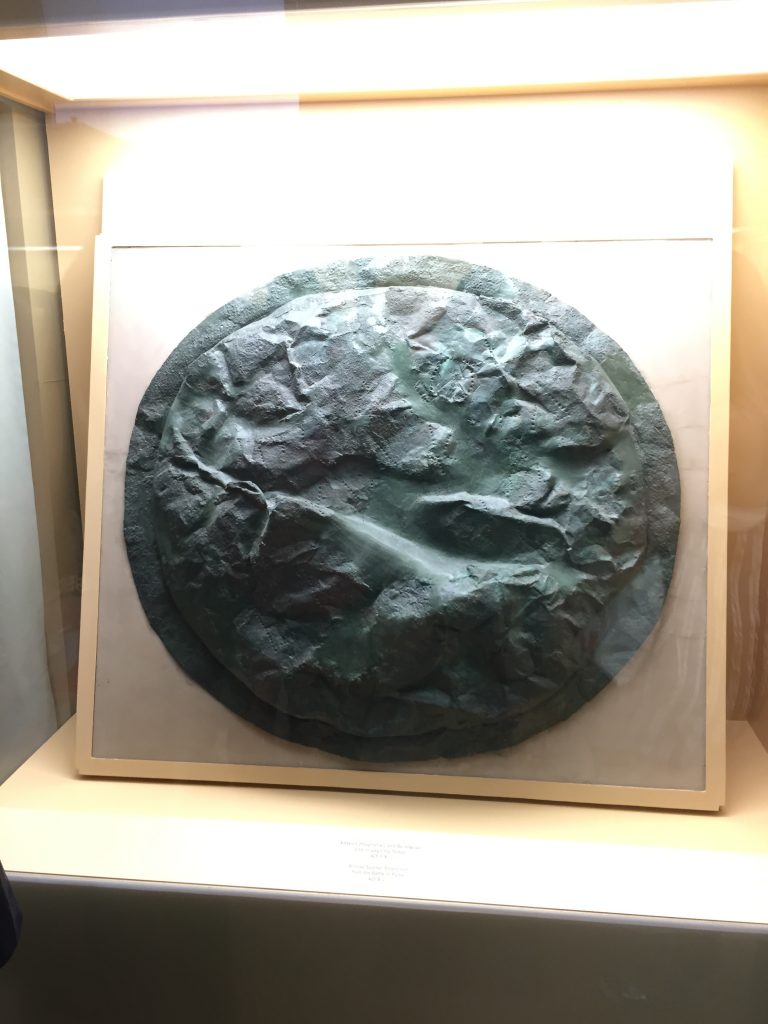

A Spartan hoplon shield in the museum

Bronze spear heads and horse bits

Ostraka with the name of ‘Themistocles’, the great Athenian general, on them

Souvlaki anyone? See this small oven and kebab sticks! People also came to eat in the Agora.

After we were finished in the museum, there was one more surprise left in the stoa. If you go to the north or south end of the stoa you will see stairs leading to the second level.

We snaked our way up the stairs on the north end to find not only a wonderful view of the agora, but also, behind walls of glass, a long row of wooden shelves where myriad artifacts are stored. It was unbelievable to stand on the other side of the glass looking into the shadowed interior to see ancient black and red vases and kraters, kylixes and more. There were Mycenaean artifacts too, and all of it just sitting there silent witnesses to the ages gone past.

Oh, just some ancient pottery tucked away on a shelf.

As we finished in the stoa and museum, we decided it was time to go. We made our way along a wall of broken monuments, displayed like ornaments in the garden of some antiquarian, each one with a story to tell of Athens’ past, each one whispering as I walked by.

I had to pull myself away from those voices, to tell them that I would see them again some day.

The day was wearing on, and there was more to do, more people to see before the end of my summer odyssey. But, I had to stand at the gates of the ancient Agora one more time and look out over the ruins of Athens’ history and up to the hopeful beacon of the Acropolis.

It is never easy to say goodbye to that ancient place, but I did so with a pang before turning and disappearing into the crowded market streets of Monastiraki and the Plaka, a part of me still wandering the Agora, haunted by history.

Finishing things off with some shopping in the Plaka.

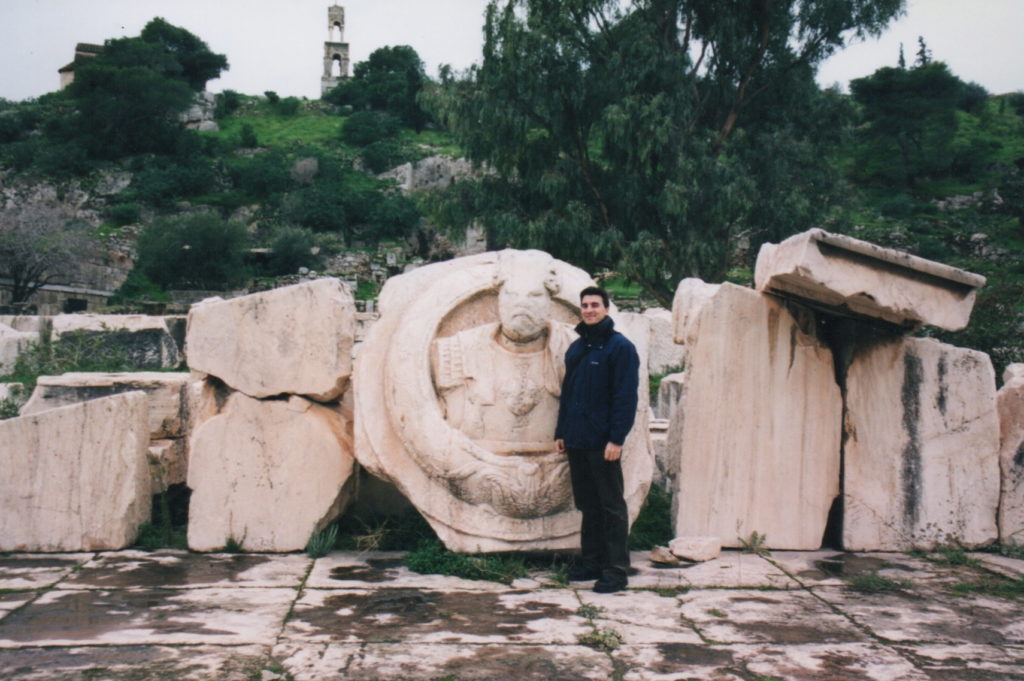

I hope you’ve enjoyed this short post on the agora of ancient Athens. If you did, you might also enjoy some previous posts on visits to Delphi, Delos, Tiryns, Epidaurus, Nemea, Eleusis, the temple of Apollo at Bassae, and Olympia.

Be sure to tune in next week as we step into the Hellenistic age with a guest post from historical fiction author Zenobia Neil.

Thank you for reading.