Hadrian

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part V – Legions in the North: The Romans in Scotland

Warriors of Epona is set against the backdrop of the Severan invasion of Caledonia (modern Scotland). It was a massive campaign, and Rome’s last major attempt at subduing the tribes north of the Antonine Wall.

However, this was not the first time Rome had attempted to invade Caledonia. In fact, Septimius Severus’ legions were using the infrastructure of previous campaigns into this wild, northern frontier.

In this fifth and final part of The World of Warriors of Epona, we’re going to look briefly at the Roman actions in Caledonia prior to and including the campaigns of Emperor Septimius Severus.

The full scale conquest of Britannia was undertaken in A.D. 43 under Emperor Claudius, with General Aulus Plautius leading the legions. Campaigns against the British tribes continued under Claudius’ successor, Nero in A.D. 68.

The conquest of the South of Britain involved overcoming the tribes, including Boudicca and the Iceni, the Catuvellauni, the Durotriges, the Brigantes, and others, and the attempted extermination of the Druids on the Isle of Anglesey.

Boudicca

Eventually, after much blood and slaughter, the South was subdued, and the Pax Romana began to take root in that part of Britannia. (It pains me to gloss over so large a part of the history of Roman Britain, but we’re talking about Caledonia here…)

It was not until A.D. 71 that Rome decided it was time to invade Caledonia, and the man assigned this task was Quintus Petillius Cerialis, a veteran of the Boudiccan Revolt, and governor of Britannia at that time.

Once Cerialis’ legions were able to break through the Brigantes, it was time to press north into Caledonia.

The person who is most associated with these initial campaigns in Caledonia is none other than Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who had served in the campaigns against Boudicca in the South and who was also governor of Britannia from A.D. 77-85.

Agricola – Statue at Roman Baths, Bath, England

In around A.D. 80, Emperor Titus (A.D.79-81) ordered Governor Agricola to begin the campaigns into Caledonia by consolidating all of the lands south of the Forth-Clyde (roughly between Edinburgh and Glasgow). This involved taking on the tribes of the Borders, including the Selgovae, Maeatae, Novantae, and Damnonii.

It is in during this campaign that the fort at Trimontium, and many others were established in the Borders.

Commemorative stone at Newstead, in the Scottish Borders

By A.D. 81, Emperor Domitian had decided to order Agricola and his legions into Caledonia, and within two years, Agricola is said to have brought the Caledonians to their knees at the Battle of Mons Graupius.

He [Agricola] sent his fleet ahead to plunder at various points and thus spread uncertainty and terror, and, with an army marching light, which he had reinforced with the bravest of the Britons and those whose loyalty had been proved during a long peace, reached the Graupian Mountain, which he found occupied by the enemy. The Britons were, in fact, undaunted by the loss of the previous battle, and welcomed the choice between revenge and enslavement. They had realized at last that common action was needed to meet the common danger, and had sent round embassies and drawn up treaties to rally the full force of all their states. (Tacitus, Agricola; XXIX)

The Roman historian, Tacitus, was actually Agricola’s son-in-law, and his account, De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae, provides us with the best first-hand account of Agricola and his invasion of Caledonia.

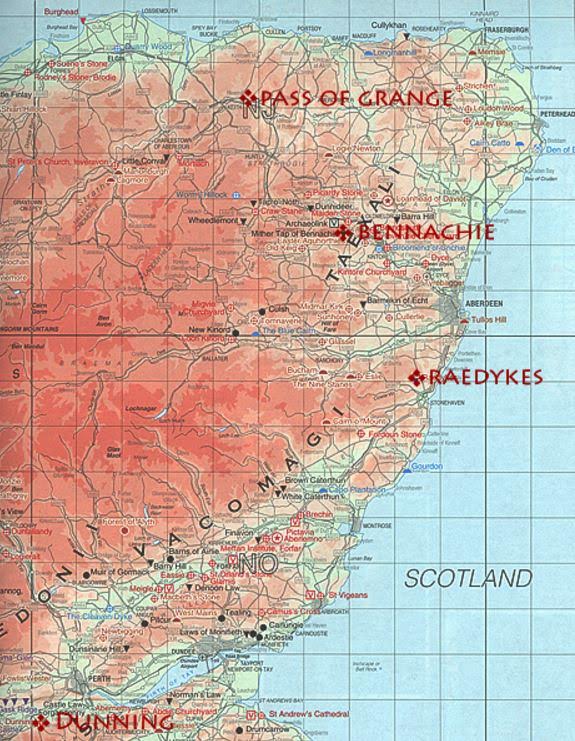

Possible locations for Battle of Mons Graupius

This is a time of legions exploring the unknown reaches of the Empire.

Sadly, the battlefield for Mons Graupius has not been identified, though there are certain candidates.

What is fortunate, however, is that Agricola’s legions left a long train of breadcrumbs in the form of marching camps, legionary bases, watch towers and of course, roads, all the way to northern Scotland.

And it is network of war that was to be used in later invasions of Caledonia.

Early Roman campaigns in Caledonia

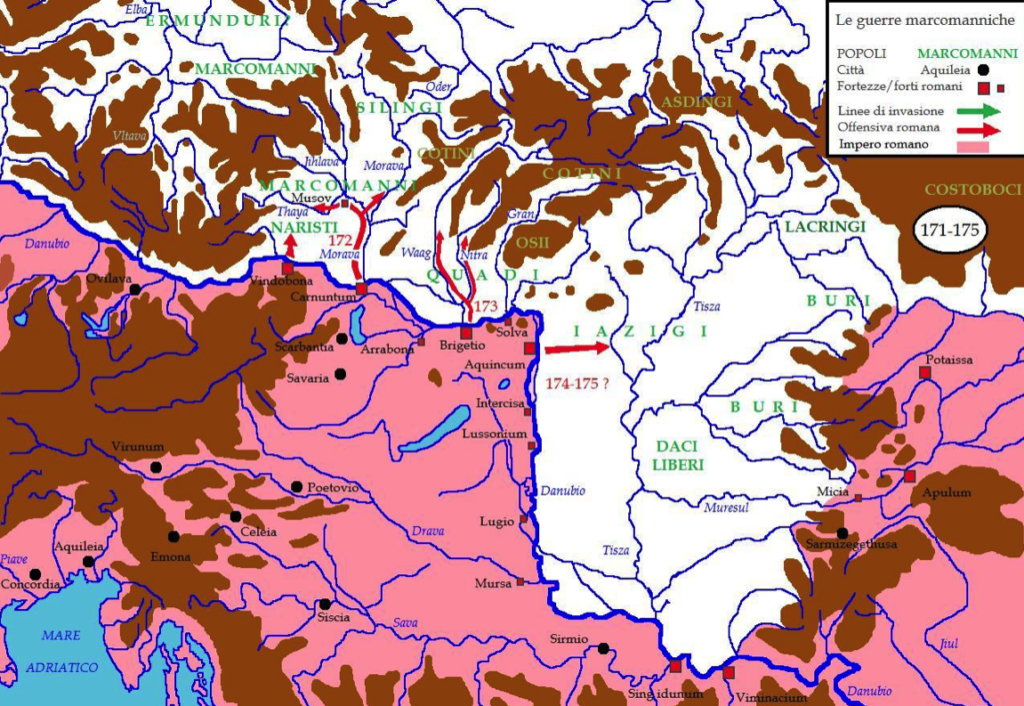

War broke out again on the Danube frontier at this time, and so Roman man-power was sucked out of Britannia and Caledonia to meet threats elsewhere in the Empire.

And so, the legions in Caledonia went into a period of retrenchment and pulled back to the Forth-Clyde by A.D. 87.

By the time of Emperor Trajan’s reign, c. A.D. 99, Rome had retreated farther to the South to the Tyne-Solway, the future line of Hadrian’s Wall, construction of which began in A.D. 122.

The Caledonian lands for which Agricola and his legions had fought, had been given up for the time being.

Hadrian’s Wall

As was the case for centuries to come, the lands between the Forth-Clyde line, and the Tyne-Solway line, the area known today as the Scottish Borders, went into a period of push and pull, of occupation, retreat, and re-occupation.

It was during the reign of Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161) that it was deemed necessary to re-occupy the lands lost during the Flavian period, and so the army advanced again across the borders, using those same roads and forts that had been constructed by Agricola, and constructing new ones.

Twenty years after construction began on Hadrian’s Wall, Antoninus Pius ordered the construction of a new wall in Caledonia itelf in A.D. 142. This was the Antonine Wall, and it’s earth and timber ramparts ran the width of Caledonia from the Forth to the Clyde in an attempt to hem the raucous tribes in on their highlands.

The Antonine Wall

But, after more campaigning and entrenchment by Rome, the Antonine Wall was abandoned during the reign of Marcus Aurelius in around A.D. 163.

A few outposts remained in use to the north of Hadrian’s Wall, but for the most part, the bones of the Empire were left to rot and be overwhelmed by the Caledonians and their allies.

For the next forty years, the northern tribes became a menace, breaking through the frontier defences twice, once during the reign of Commodus (c. A.D. 184) and then again during the early part of Septimius Severus’ reign in A.D. 197.

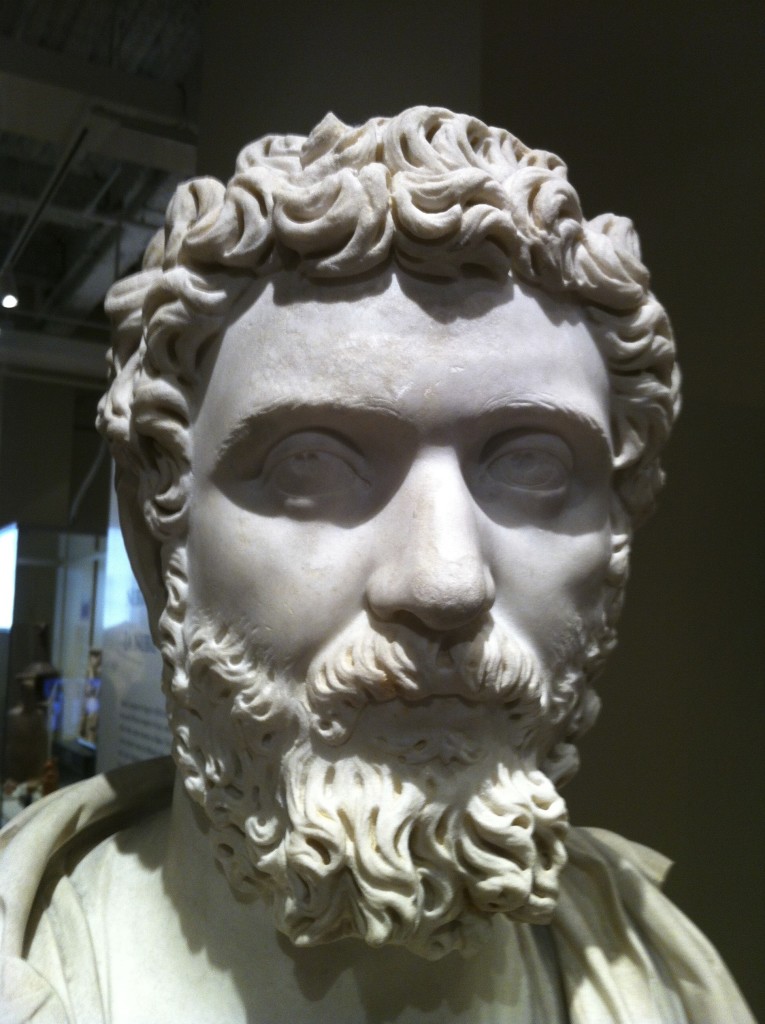

Septimius Severus

When Septimius Severus took the imperial throne, he was immediately engaged in consolidating the Empire after the civil war, and then taking on the Parthian Empire. He was a military emperor, and he knew how to keep his troops busy, and how to reward them.

The Caledonians had been a thorn in Rome’s side for a long while at that time, but it was not until A.D. 208 that Severus was finally able to deal with them. And so, the imperial army moved to northern Britannia, poised to take on the Caledonians once again.

We’ve already touched on Severus’ campaign in previous parts of this blog series. However, it’s important to note that this is believed to be the last real attempt by Rome to take a full army into the heart of barbarian territory.

Severus moved on the Caledonians with the greatest land force in the history of Roman Britain, making use of his predecessors’ fortifications (such as the Gask Ridge frontier) and roads, and penetrating almost as far as Agricola’s legions over a hundred years before.

According to Cassius Dio, when the inhabitants of the island revolted a second time, Severus:

…summoned the soldiers and ordered them to invade the rebels’ country, killing everybody they met; and he quoted these words: ‘Let no one escape sheer destruction, No one our hands, not even the babe in the womb of the mother, If it be male; let it nevertheless not escape sheer destruction.

Rome was poised for a final push, and ultimate victory over the Caledonians.

Goddess Fortuna

But Fortuna was not on Severus’ side, for it was at that time that his chronic health problems finally got the better of him.

In A.D. 211, the man who had won a brutal civil war, and who had finally brought the Parthians to heel, died at Eburacum (modern York) in Britannia.

Roman Tower at Eburacum (York)

His son, Caracalla, who was ill-equipped to handle the situation, struck a deal with the Caledonians, abandoning all the headway his father had made in that northern land, and all of the blood shed by fifty-thousand Romans in the Severan campaign.

What happened after the death of Severus is for another story (i.e. for the next book!). However the Severan conquests in Caledonia did usher in a fleeting period of tranquility.

Later expeditions into the North were mounted in c. A.D. 296 by Constantius Chlorus, and by his son, the future Emperor Constantine, in A.D. 306. However, neither of these campaigns were on a scale comparable to the Severan campaign.

Like other remote corners of the Empire, Caledonia must have seemed like a lost cause.

Roman Cavalry

But the Eagles and Dragons series is not yet finished with this exciting period of history in Roman Britain. Like Severus, we are poised for a final punitive push into the Highlands.

It’s a fascinating period in Roman history, and I hope you have enjoyed this journey through The World of Warriors of Epona with me. If you missed any of the previous blog posts in this series, you can read them all on one page by CLICKING HERE.

If you would like to learn a bit more about the Romans in Scotland, I highly recommend checking out the documentary Scotland: Rome’s Final Frontier with Dr. Fraser Hunter.

Warriors of Epona is out now on Amazon, Apple iBooks/iTunes, and Kobo, so be sure to get your copy today.

Remember, if you haven’t yet read any of the Eagles and Dragons novels, and if you want to get stuck in, you can start with the #1 Best Selling prequel novel, A Dragon among the Eagles. It’s a FREE DOWNLOAD on Amazon, Apple iTunes/iBooks, and Kobo.

Thank you for reading!

The World of Killing the Hydra – Part V – Desert Legion: The Fortress of Lambaesis – Imagining Saharan Frontier Life

What was it like to live on the very edge of the Roman Empire?

When writing Killing the Hydra, this was something I asked myself many times. What was life like for soldiers, commanders, women, children, and locals under Roman rule? What was it like to be so isolated in a place that, for many, sat on the precipice of the known world?

The Numidian Desert – the Sahara in modern Algeria

In this fifth and final part of The World of Killing the Hydra, we’re going to look at the place where Lucius Metellus Anguis is posted to, and where his family joins him – the legionary base at Lambaesis.

Lambaesis was located in the province of Numidia (modern Algeria), and was the base for the III Augustan legion at the beginning of the third century A.D. when this story takes place. Lambaesis was established by Emperor Hadrian between A.D. 123-129 when the III Augustan legion moved there.

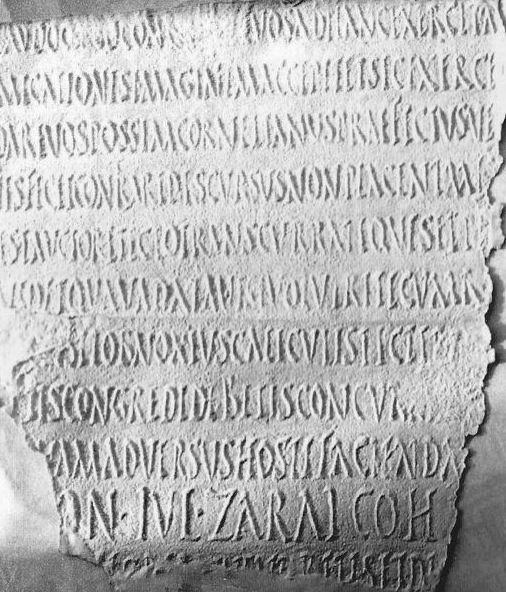

Hadrian toured the Empire and on his visit to Lambaesis, he addressed the troops of this desert legion. Evidence of this address has come down to us in the form of a pillar inscription that was located on the large outdoor parade ground of the base.

Part of the inscription from Lambaesis documenting Hadrian’s address to the troops when he visited there.

The III Augustan legion, however, was older than that. It originated under Pompey the Great in the civil war against Julius Caesar and was eventually moved to North Africa in 30 B.C. by Octavian (who became Augustus) after his victory over Mark Antony.

Eventually, the III Augustan came to be based at Lambaesis, one of only two Roman legions in North Africa, the other being based in Aegyptus.

The III Augustan played an important role in the security and urbanization of North Africa, helping to build roads, aqueducts, fortifications, theatres and more. This work in turn connected towns and cities, facilitated trade, and provided protection for outlying settlements. The work of the army engineers and surveyors brought Roman civilization to this remote frontier.

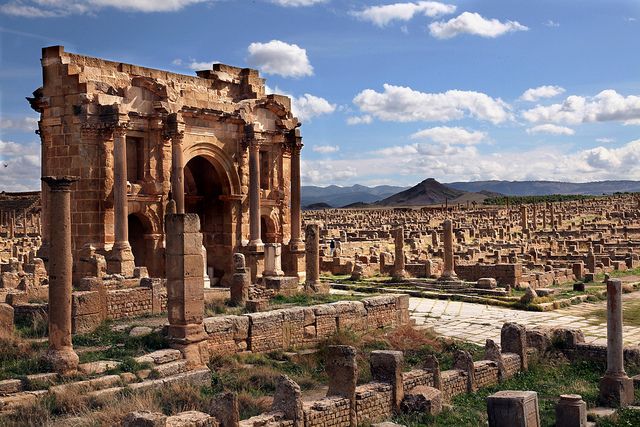

The Praetorium of Lambaesis

The III Augustan was a veteran legion, and of the remains present in that place, apart from the arches of Septimius Severus and Commodus, temples, baths and cemeteries, the principia with its open courtyard is the most stunning of its remains.

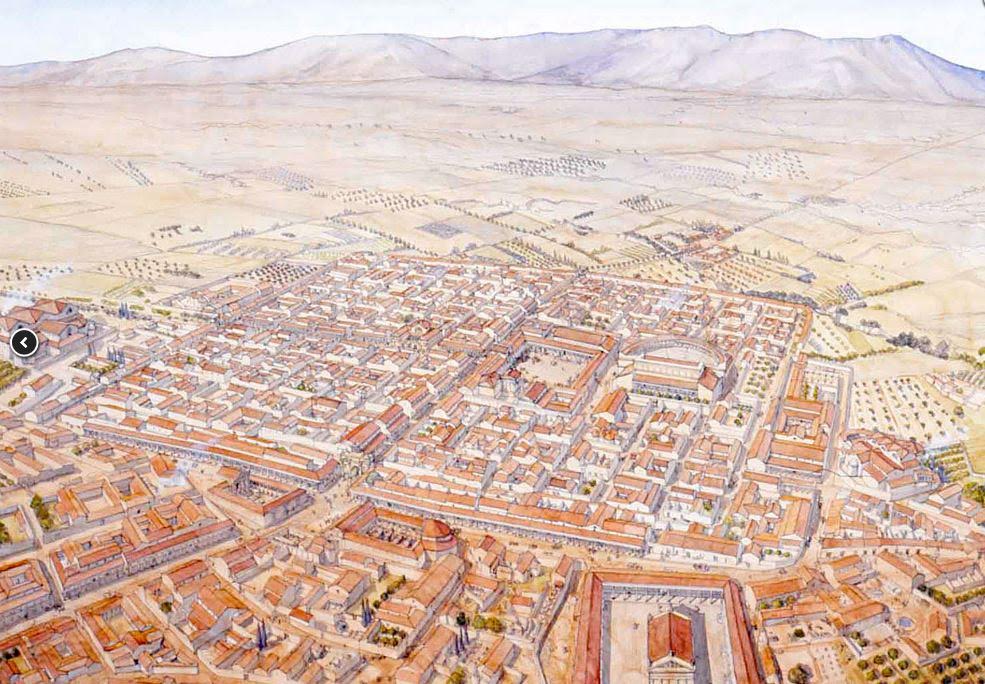

This base was on the edge of the deep desert in modern Algeria, backed by the Aures Mountains. At first glance, this seems to have been a lonely windswept place, just as it is today. However, during the Roman period, Lambaesis would have been a busy, thriving place.

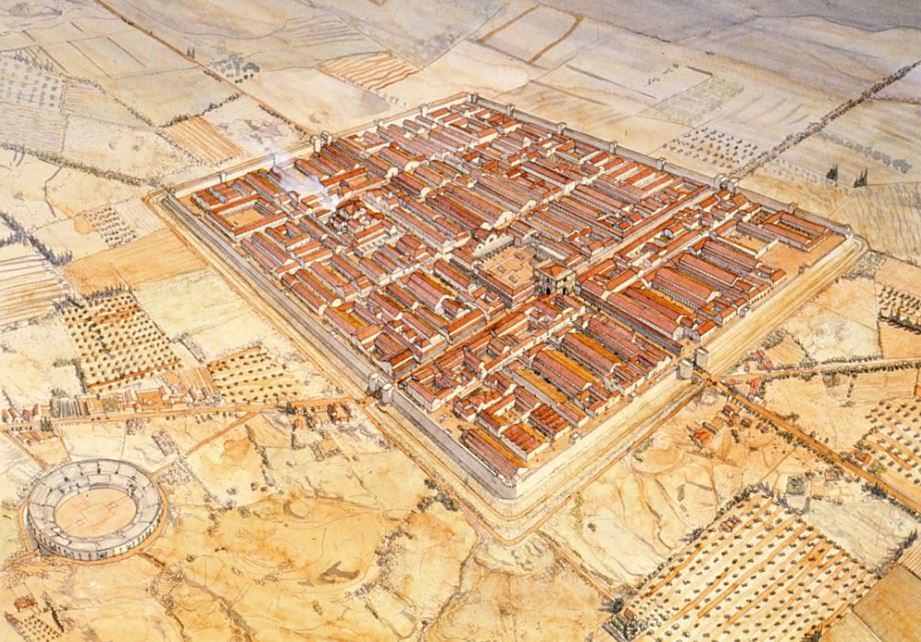

Artist impression of Lambaesis by Jean Claude Golvin

This was not so much an active frontier like that of the Danube or Parthian fronts, but rather a more peaceful place, punctuated with occasional incursions by Garamantians, nomadic Berber tribes and others.

For the most part, the veterans of the III Augustan took part in public building works and improvements, as well as patrols. The men of the legions were a part of society at Lambaesis and the surrounds.

Previously, men of the legions were not permitted to marry, but this law was changed under Septimius Severus, and so many men would have had families living in the vicus outside the base’s walls, or in some instances within the walls.

Add to this the presence of the large, prosperous colonia of Thamugadi, just seventeen miles away, and you have a frontier that was busy, social, and economically vibrant.

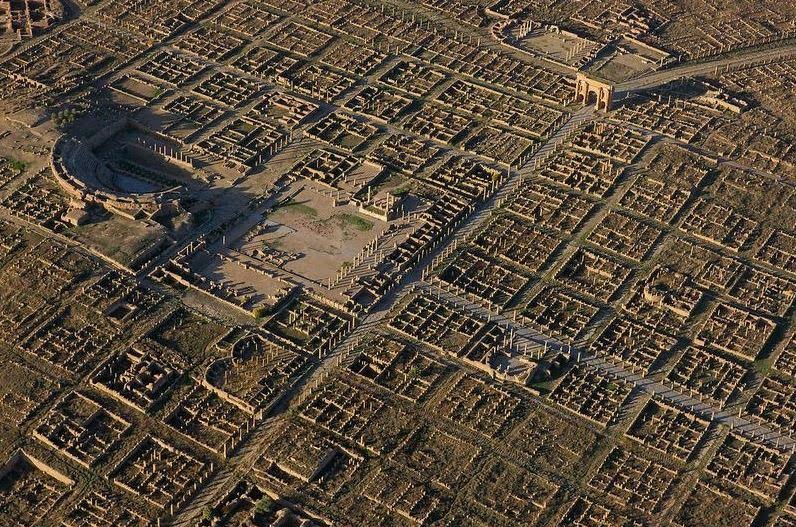

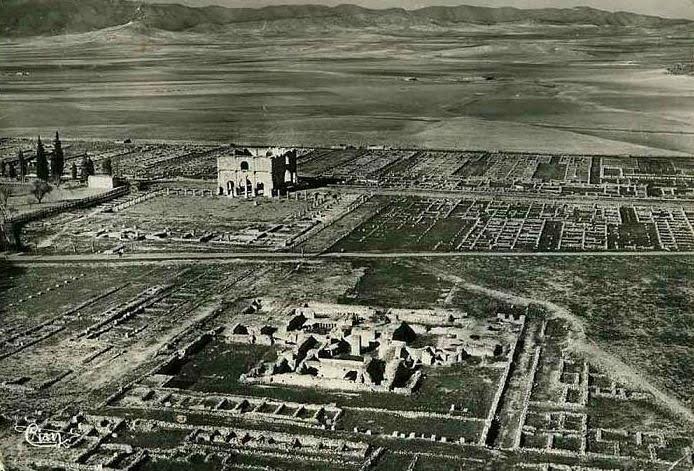

Aerial view of the colonia of Thamugadi

The colonia of Thamugadi was where veterans of the III Augustan legion retired to once their military service was at an end. It was founded by Emperor Trajan in about A.D. 100 under the name of Marciana Traiana Thamugadi. It was a walled settlement, but not fortified, and had a population of about 15,000.

Today, it is made up of some of the most intact and vast ruins of Roman North Africa, including the well-preserved arch of Trajan. It had twelve public baths, theatres, a public library, a basilica and a magnificent temple of Jupiter.

The arch of Trajan in Thamugadi

One imagines that it was lonely for soldiers’ wives and their children, being posted to such a remote location, compared with other parts of the Empire, but with the changed laws regarding marriage for troops, the close proximity of Thamugadi to Lambaesis, and the thriving economy of Roman North Africa at this point in time, it seems like Saharan frontier life may not have been the sort of lonely, wasteland existence that I had in mind when I started my research and writing.

I always try to travel to the places I am writing about, but sometimes that just isn’t possible, or safe. Lambaesis was one of those places.

At the time of my Tunisian research for Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra, we were told there was a travel ban to Algeria where the remains of both Lambaesis and Thamugadi are located.

Artist impression of Thamugadi by Jean Claude Golvin – this was not a tiny village, but a bustling settlement!

Our 4X4 skirted the military border between the two countries, distant guard towers and barbed wire visible as a long grey line cutting across the North African landscape.

We asked our guide if we could drive into Algeria but he was adamant that it wasn’t possible. “No chance. It is forbidden. They will shoot at us,” he said.

I don’t know if that was true or not, but some things are not worth the risk. After all, we have the internet now and a myriad of resources on-line.

So, we had to settle for pulling our truck over on the gravelly roadside and gazing westward across the guarded border to the Aures Mountains of Algeria and imagining what remnants of Rome lay scattered in that vast expanse.

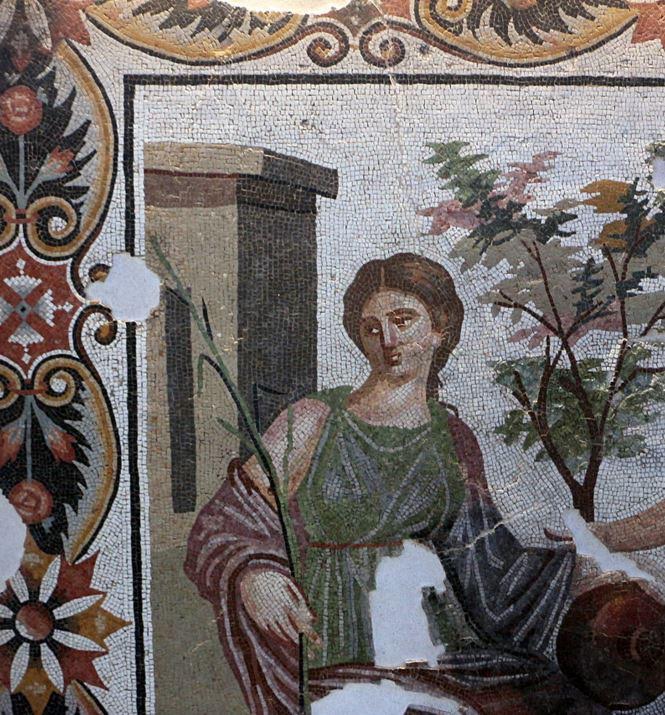

Mosaic fragment from Lambaesis

The light was dull that day, an iron-grey winter sky, so the feeling of loneliness and desolation was acute. Somewhere out there was the base of the veteran III Augustan legion. There was a colonia for veterans filled with the amenities of Roman civilization.

This was a land where my character was to be posted, along with his family, and the families of his fellow officers and troops. Many would have had family and friends in Thamugadi, done business there, and used the network of roads that really did, in one way or another, lead back to Rome…

It was hard to imagine as I stood there with the dust whipping around us, our guide looking nervously in our direction as if we might attempt something stupid.

The relief on his face when we said “OK. Let’s go.” was darkly comic. It was also real.

But maybe that hints at Saharan frontier life in the Roman Empire?

Aerial view of Lambaesis