Salvete Readers and Romanophiles!

Welcome back to The World of Sincerity is a Goddess, the blog series in which we delve into the research that went into the dramatic and romantic comedy of ancient Rome, Sincerity is a Goddess.

If you missed Part VI on the theatre and healing sanctuary of ancient Epidaurus, you can read that by clicking HERE.

Today, in Part VII of this blog series, we’re going to be sticking with the healing theme, only this time from the Roman perspective rather than from the Greek one, though they are related.

In this post, we’re going to be taking a look at doctors in the Roman Empire, as well as that famed centre of healing in the heart of ancient Rome, Tiber Island.

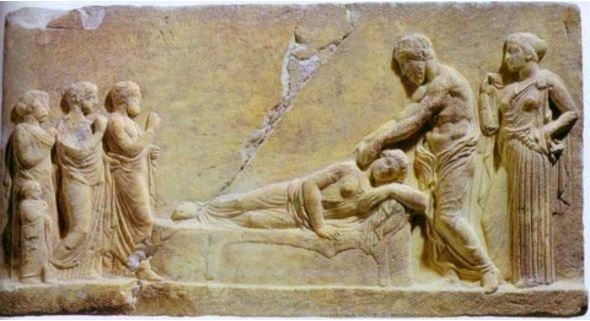

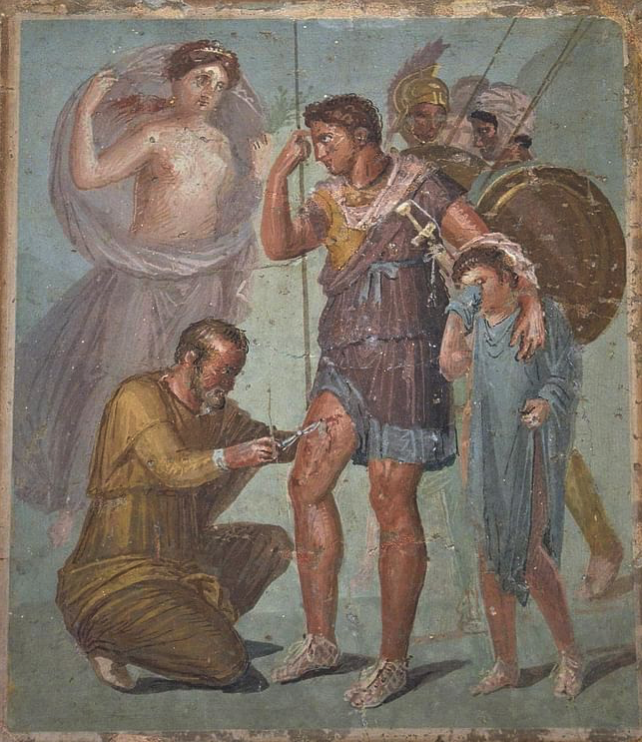

A doctor making a house call.

Going to the doctor’s office is never something one looks forward to.

For most, myself included, it gets the heart rate and stress levels up to step into a building that’s full of ‘sick people’. With our modern plague, I’m sure many of us are feeling that.

Sitting around in a waiting room with a group of scared, nervous, fidgety folks, is enough to drive you mad, and the sight of a white coat and stethoscope makes one want to run screaming from the building.

In a way, it was probably the same for our ancient Greek and Roman ancestors. Most civilians would have been loath to visit with a physician. It might not have been someone you wanted around, unless absolutely necessary.

When it comes to physicians in the Roman Empire, it has to be said that many, if not most, were Greek, and that’s because Greece was where western medicine was born. Indeed, the ancient Greeks had patron gods of health and healing in the form of Asklepios, Igeia, and sometimes Apollo.

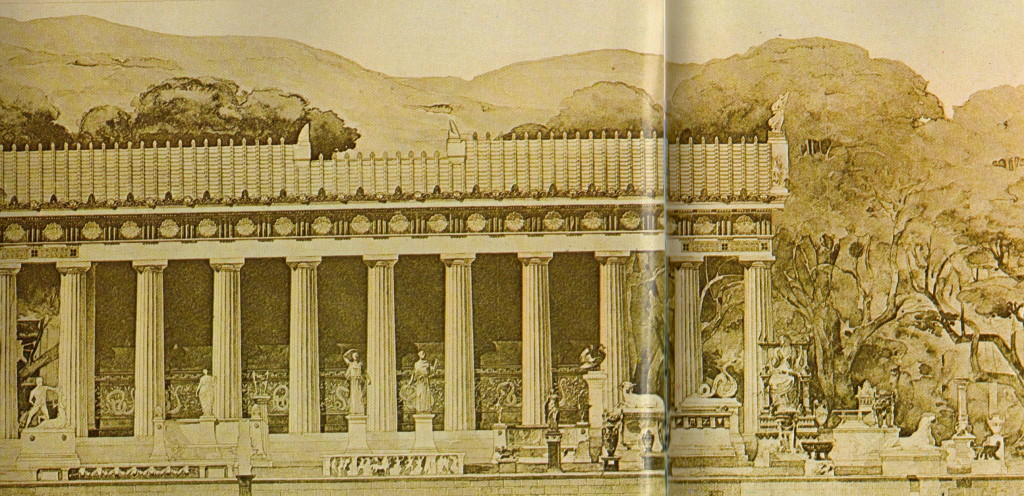

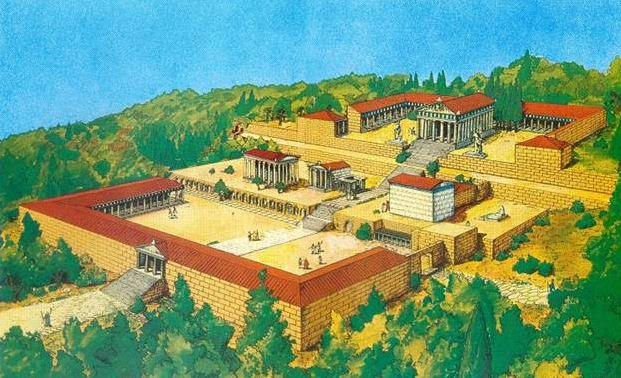

Artist rendering of the Asklepion of Kos

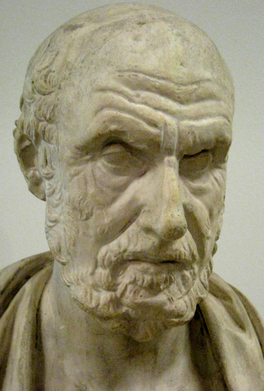

The greatest medical school of the ancient world was in fact on the Aegean island of Cos, where students came from all over the Mediterranean world to learn at the great Asklepion. Hippocrates, the 5th century B.C. ‘father of medicine’, was from Cos and said to be a descendant of the god Asklepios himself.

When it comes to Roman medicine, much of it is owed to what discoveries and theories the Greeks had developed before, but with a definite Roman twist.

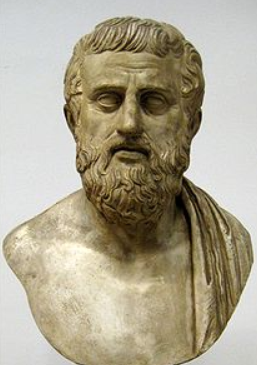

Hippocrates

The fusion of Greek and Roman medicine in the Roman Empire consisted of two parts: the scientific, and the religious/magical.

The more scientific thinking behind ancient medical practices is a legacy owed to the Greeks, who separated scientific learning from religion. The religious, or rather superstitious, aspects of medicine in the Roman Empire were a Roman introduction.

Because of this fusion of ideas and beliefs, you could sometimes end up with an odd assortment of treatments being prescribed.

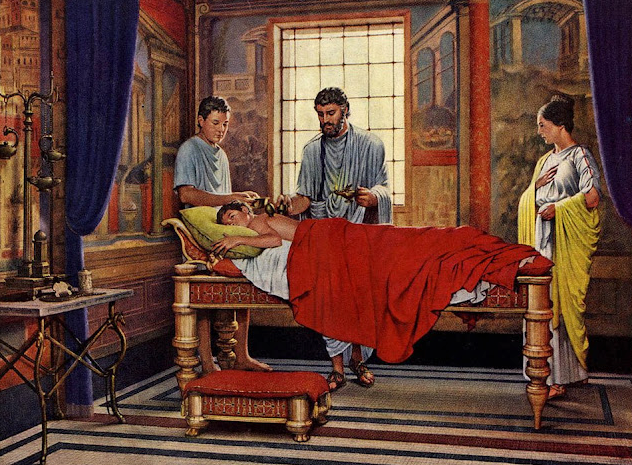

A Roman physician blood letting (by Robert Thom, c. 1958)

To alleviate your anxiety over your new business venture, you should take three drops of this tincture before you sleep. You should also sacrifice a white goat to Janus as soon as possible.

Many Roman deities had some form of healing power so it depended on one’s patron gods, and the nature of the problem, as to which god would receive prayers or votive offerings over another. Amulets and other magical incantations would have been employed as well.

Roman surgical instruments

Romans had a god for everything, and soldiers were especially superstitious.

Much of Greek medical thought opted for practicality in the treatment of wounds, and injuries; cleaning and bandaging wounds would have been more logical than putting another talisman about the neck. That said, let us not forget the aspect if divine intervention when it came to some aspects of healing in such places as Epidaurus.

All the gods were to be honoured, but in the Greek physician’s mind they had much better things to look after than the stab wound a man received in a tavern brawl.

Battlefield medics treating wounded soldiers on Trajan’s Column

For the battlefield medicus, things must have been much simpler than for the physician who was trying to diagnose mysterious ailments for someone in the heart of Rome. They were faced mostly with physical wounds and employed all manner of surgical instruments such as probes, hooks, forceps, needles and scalpels.

Removing a barbed arrowhead from a warrior’s thigh must have required a little digging.

Of course, in the Roman world, there was no anaesthetic, so successful surgeons would have had to have been not only dexterous and accurate, but also very fast and strong. Luckily, sedatives such as opium and henbane would have helped.

Medic helping a warrior tend a wound

When it came to the treatment of wounds, a medicus would have used wine, vinegar, pitch, and turpentine as antiseptics. However, infection and gangrene would have meant amputation. The latter was probably terrifyingly frequent for soldiers, many of whom would end up begging on the streets of Rome.

It is interesting to note that medicine was one of the few professions that were open to women in the Roman Empire. Female doctors, or medicae, would also have been mainly of Greek origin, and either working with male doctors, or as midwives specializing in childbirth and women’s diseases and disorders. When it came to the army however, most doctors would have been male.

Ancient surgical instruments, including forceps

Army surgeons played a key role in spreading and improving Roman medical practice, especially in the treatment of wounds and other injuries. They also helped to gather new treatments from all over the Empire, and disseminated medical knowledge wherever the legions marched. Many of the herbs and drugs that were used in the Empire were acquired by medics who were on campaign in foreign lands.

Early on, physicians did not enjoy high status. There was no standardized training and many were Greek slaves or freedmen. This began to improve, however, when in 46 B.C. Julius Caesar granted citizenship to all those doctors who were working in the city of Rome.

This last point really hits home when it has become common knowledge that foreign doctors who come to our own countries today find themselves driving taxis or buses because they are not allowed to practice.

Modern governments, take your cue from Caesar!

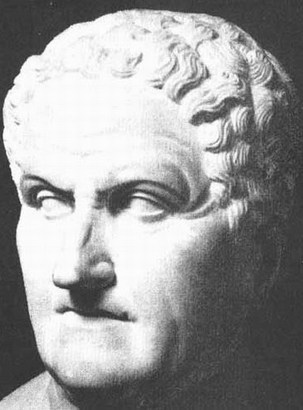

Galen

One of the most famous physicians of the Roman Empire is Galen of Pergamon (A.D. 129-c.199). Galen was a Greek physician and writer who was educated at the sanctuary of Asklepios at Pergamon in Asia Minor.

After working in various cities around the Empire, Galen returned to his home town to become the doctor at the local ludus, or gladiatorial school. He grew tired of that work and moved to Rome in A.D. 162 where he gained a reputation among the elite. He subsequently became the personal physician of the Emperors Marcus Aurelius, Commodus, and for a short time, Septimius Severus.

Galen’s work and writings provided the basis of medical teaching and practice on into the seventeenth century. No doubt many an army medicus referred to Galen’s work at one point or another.

Galen is also an important character in A Dragon among the Eagles, the prequel in the Eagles and Dragon series. In the book, Galen, an old friend and colleague of Lucius Metellus’ late tutor, presents Lucius with a choice that could well change the direction of Lucius’ life. In fact and fiction, Galen is a fascinating person of history.

Re-created ancient surgical instruments

There was, of course, a difference between medical procedures that were frequently carried out on civilians in Rome versus what was needed on the battlefields of the Empire.

I’m not an expert in ancient medical history, but I do know that the level of injury on an ancient battlefield would have been staggering. The sight or sound of your unit’s medicus would have been something sent from the gods themselves.

Imagine a clash of armies – thousands of men wielding swords, spears and daggers at close quarters. Then lob some volleys of arrows into the chaos. Perhaps a charge of heavy cavalry? How about heavy artillery bolts or boulders slamming into massed ranks of men?

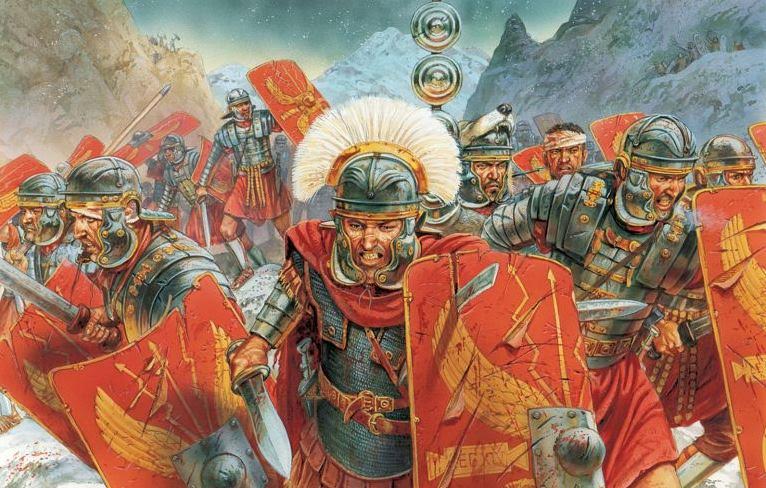

Roman Legionaries (illustrated by Peter Dennis)

It would have been one big, bloody, savage mess.

Apart from the usual cuts, slashes, and puncture wounds, the warriors would have suffered shattered bones, fractured skulls, lost limbs, severed arteries, sword, spear and arrow shafts that pushed through armour on into organs.

If you weren’t dead right away, you most likely would have been a short time later.

This is where the ancient field medic could have made the difference for an army. He would have been going through numerous patients in a short period of time. He would have had to decide who was a lost cause, who could no longer fight, and who could be patched up before being sent back out onto the field of slaughter.

The medicus of a Roman legion was an unsung hero whose skill was a product of accumulated centuries of knowledge, study, and experience.

Model showing Tiber Island

When it came to ancient Rome, the centre of health and healing was Tiber Island, and its foundation has a most fascinating story…

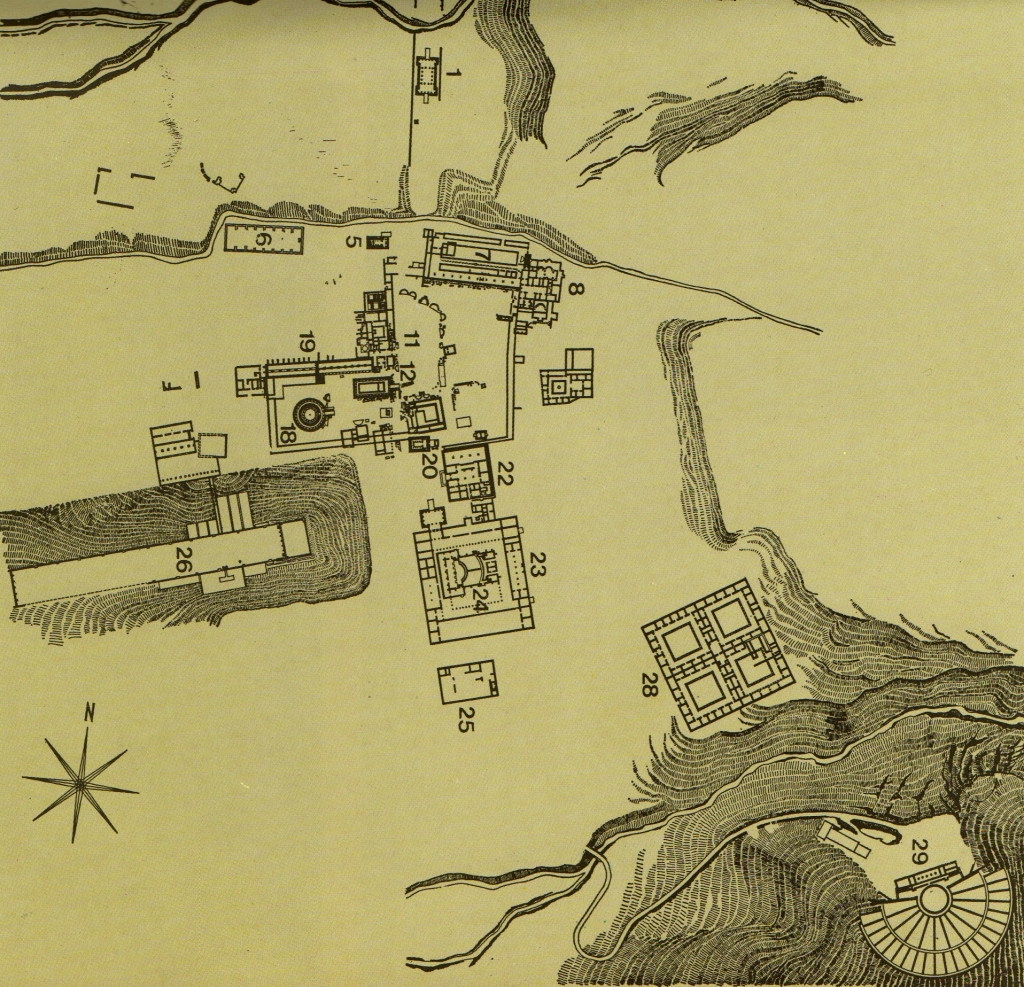

Tiber Island is a boat-shaped mass in the middle of the River Tiber where it runs through Rome. It was connected to the Field of Mars by the Pons Fabricius, and to the right bank, where modern Trastevere is, by the Pons Cestius.

The legend goes that the island was formed when, after the fall of the Etruscan tyrant, Tarquinius Superbus, in 510 B.C., the angry Romans threw his body into the Tiber where silt subsequently formed around it.

Another legend is that after the same tyrant died, the people hated him so much that they took all of his grain stores and threw it all into the river where it became the island.

Sic semper tyrannis, as the Romans would say…

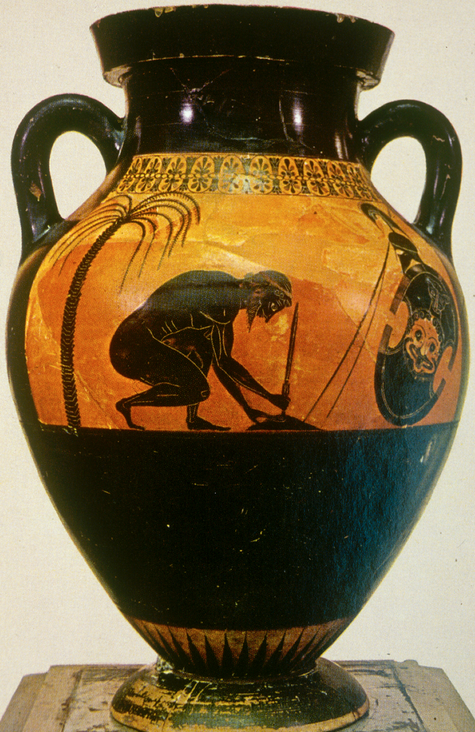

Tarquinius Superbus

Whatever the reason for the creation of Tiber Island, it seems that it was, early on, a place to be avoided as it was where criminals and the terminally ill were sent.

The story gets very interesting in 293 B.C. when a great plague hit Rome.

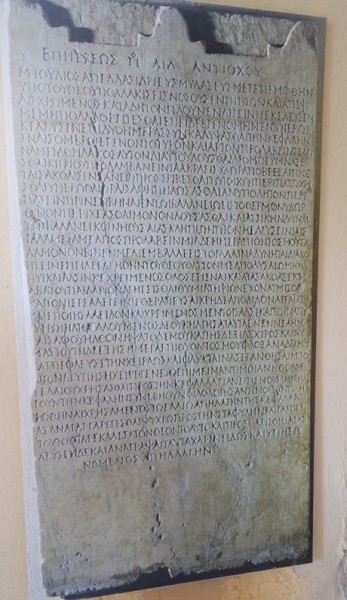

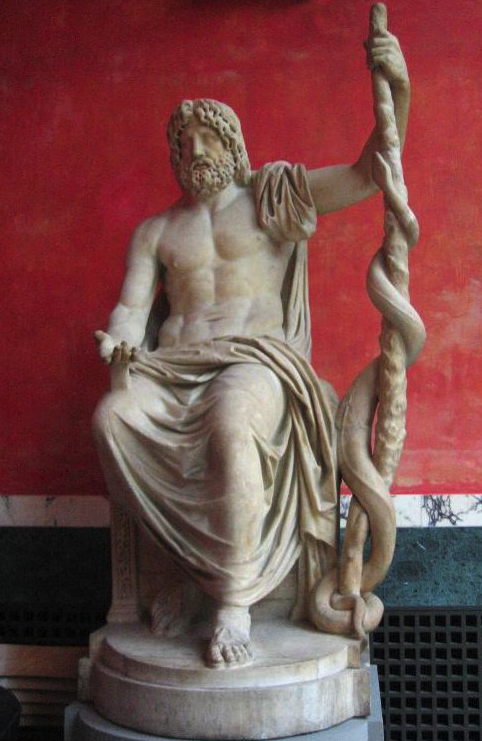

When the plague arrived, the Senate consulted the Sibyl, the Oracle of Apollo at Cumae, who told the Romans that they should build a temple to Aesculapius (Asklepios in Greek) in the city of Rome.

A delegation of Romans was sent to Epidaurus where Aesculapius’ most famous sanctuary was located, so that they could obtain a statue of the god for the proposed temple.

The delegation also obtained one of the sacred snakes from Epidaurus.

Aesculapian Snake – zemenis longissimus (Wikimedia Commons)

The story goes that as soon as the delegation returned to their ship with the statue and sacred serpent, the snake immediately curled itself about the main mast for the return journey to Rome. They took this as a good omen.

When the ship sailed down the Tiber and entered the city of Rome, the snake moved, slithered off of the ship into the water, and swam to Tiber Island where it settled itself.

The Romans took it as a sign that this was where they should build the temple of Aesculapius.

Since that time, Tiber Island has been identified with that ship, and even modelled to resemble it with travertine facing forming it to look like a ship’s prow and stern in the first century B.C., and an enormous obelisk erected to represent the mast of the ship that brought the statue and sacred serpent to Rome from Greece.

One can still see the carving of Aesculapius’ rod and serpent on the ship’s prow to this day!

Carving of the serpent and rod on the ‘prow’ of Tiber Island

In time, other shrines were built on Tiber Island such as to Jupiter Jurarius (Guarantor of Oaths), Semo Sancus Dius Fidius (Witness of Oaths), Faunus (the spirit of Boundaries), Vediovis (God of Healing), Tiberinus (the River God), and to Bellona (Goddess of War).

There was also a festival of Aesculapius and Vediovis every year on the first of January.

Just as it is today, good health was important to the Romans!

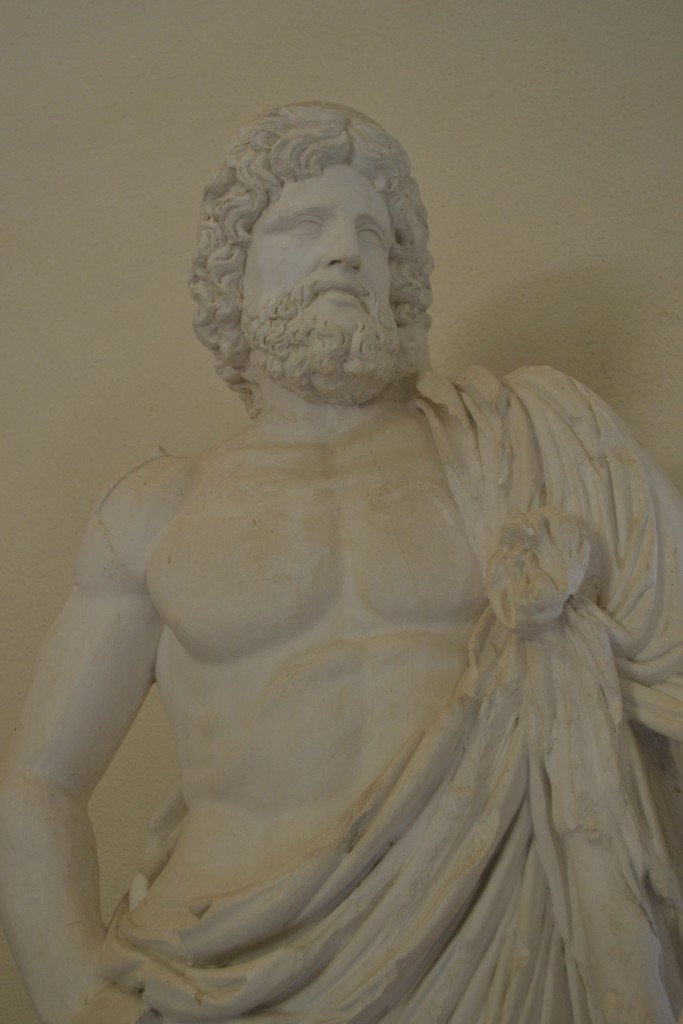

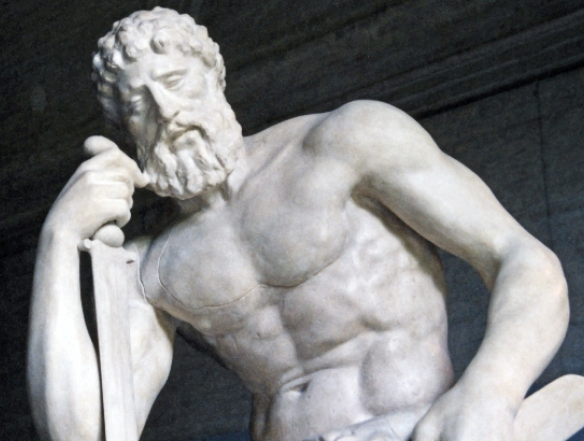

Statue of Aesculapius (Asklepios)

With the establishment of the sanctuary of Aesculapius on Tiber Island, the healing practices of Epidaurus were brought to Rome, including the use of the sacred snakes which were, it is believed, the species known as zemenis longissimus, a non-venomous serpent that could grow up to two meters in length.

The doctors also employed the use of sacred dogs whose licks were said to be healing for some patients. It is not surprising, I suppose, considering that some dogs can sniff out cancer, or restore circulation to injured limbs through licking.

Do the practices of the doctors of Tiber Island actually work in the story of Sincerity is a Goddess? Well, you have to read the book to find out. There is, we can say with certainty, a bit with a dog, a doctor with some interesting prescriptions, healing dreams, votive offerings, and a connection between Rome and ancient Epidaurus that is certainly felt on a deep level.

Votive fingurine of a ‘healing dog’ (Museum of Wales)

I’ve but barely scratched the vast surface on this topic.

For some, there is this assumption that ancient medicine was somehow false, crude and barbaric. But modern western medicine owes much to the Greeks and Romans, civilian and military, who travelled the Empire caring for their troops and gathering what knowledge and knowhow they could.

The fusion of science, religious practice, and magic provides for a fascinating mix. In truth, medical practices in medieval Europe were more barbaric than in the ancient world.

We owe much to the followers of Aesculapius and the traditions that flowed from ancient Epidaurus to the heart of Rome where there is still a working hospital on Tiber Island.

Thank you for reading.

Sincerity is a Goddess is now available in hardcover, paperback, and ebook from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortal chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy and get ISBN#s information for the edition of your choice.