Salvete Readers and Romanophiles!

At long last, we’re back with another ‘World of’ blog series! We know that most of you really do enjoy these deep dives into the research related to each of our books, so we’re happy to get stuck in!

If the title of this blog wasn’t a giveaway, this new blog series is about the research for our newest novel, Sincerity is a Goddess: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome.

In this blog series, we’ll be releasing a new post every two weeks or so on a wide range of topics related to theatre, humour, festivals, healing, playwrights and actors, and more. We do hope you enjoy it!

And now, without further ado, let’s step into The World of Sincerity is a Goddess!

In this first post, we’re going to be taking a brief look at drama and actors in the world of ancient Rome. Both, of course, are central to Sincerity is a Goddess.

Let’s start with a look at the evolution of drama in Rome.

Life is like a play in the theatre: it does not matter how long it lasts, but how well it was played.

Seneca

There are many different forms of literary arts today, just as there were in ancient Rome. Actually, in Rome, no matter the literary form, there was something for everyone. You didn’t even have to be able to read to enjoy literature of a sort.

Literary sources that we know of from the world of ancient Rome include such things as histories, speeches, poems, plays, practical manuals, law books and biographies, treatises and personal letters.

More often than not, authors in ancient Rome were well-educated and even very wealthy, and as a result, the opinions often expressed in literature reflected the values of the upper classes either because the authors were of that class themselves, or because they were patronized by the wealthy.

The main types or classifications of literature were drama, poetry, prose and satire. Though much was written in each of these areas in ancient Rome, in some cases, very little has survived, which makes this a sort of tragedy in and of it self. For the purposes of this post, we’re going to be taking a look at drama.

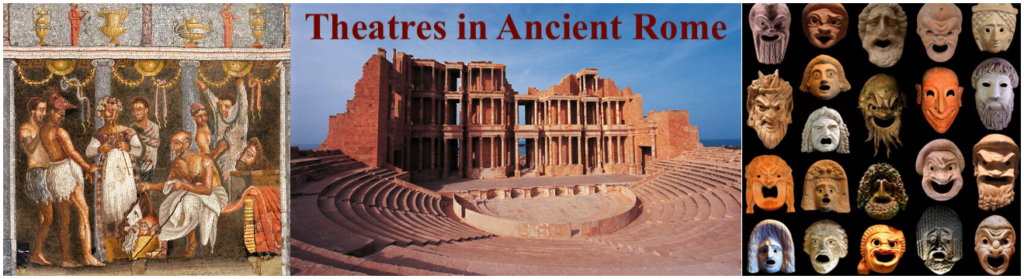

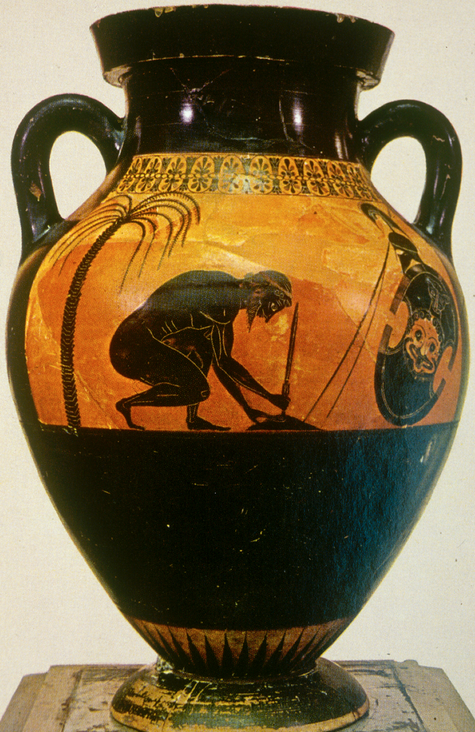

An array of Greek theatre masks

Drama is central to Sincerity is a Goddess. It was performed in Rome since before the 3rd century B.C., and these early performances took the form of mimes, dances, and farces.

One example of these early forms of drama were the fabula atellana which originated in the town Atella. These were a collection of vulgar farces that contained a lot of low or buffoonish comedy and rude jokes. They were often improvised by the actors who wore masks.

Mimes were very similar and were dramatic performances by men and women that were more licentious in nature. They were highly popular, especially with the lower classes, but they have also been accused of being the cause of the decline of comedy in ancient Rome. By the early sixth century A.D. they were banned or suppressed.

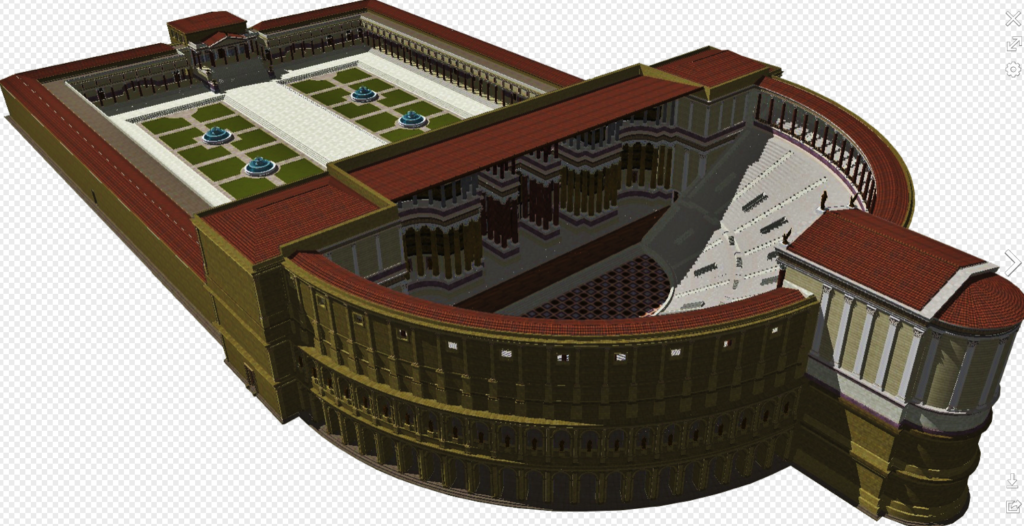

Roman Theatre in Orange (Wikimedia Commons)

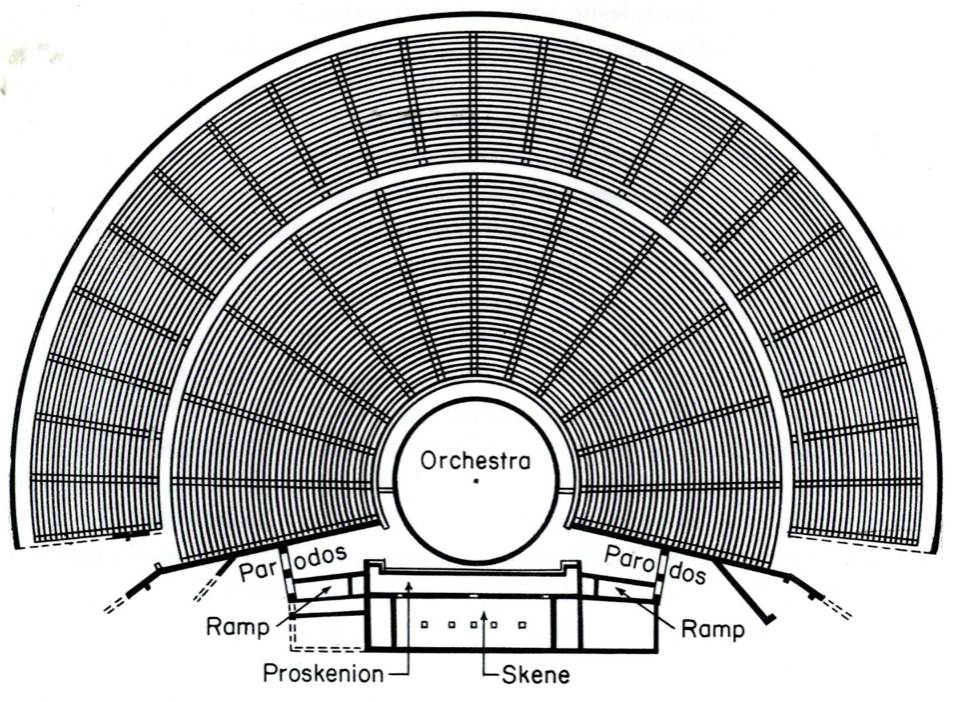

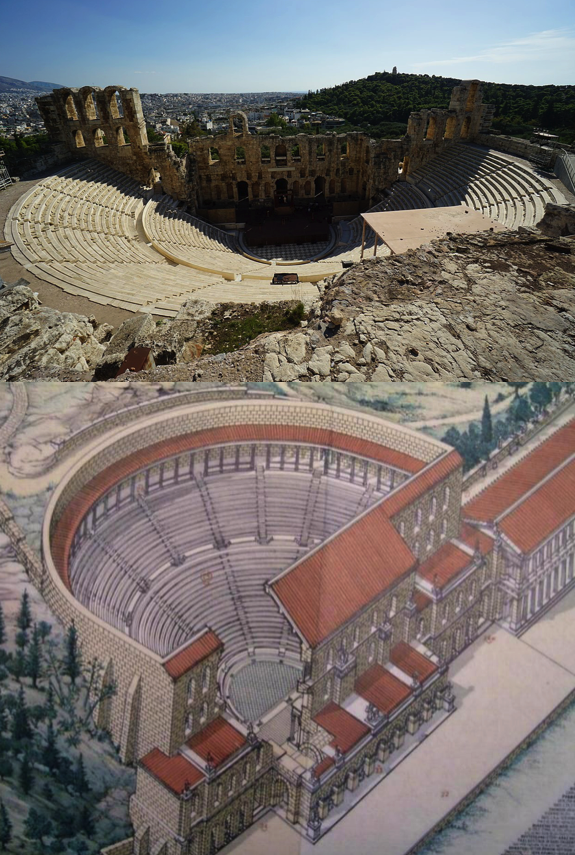

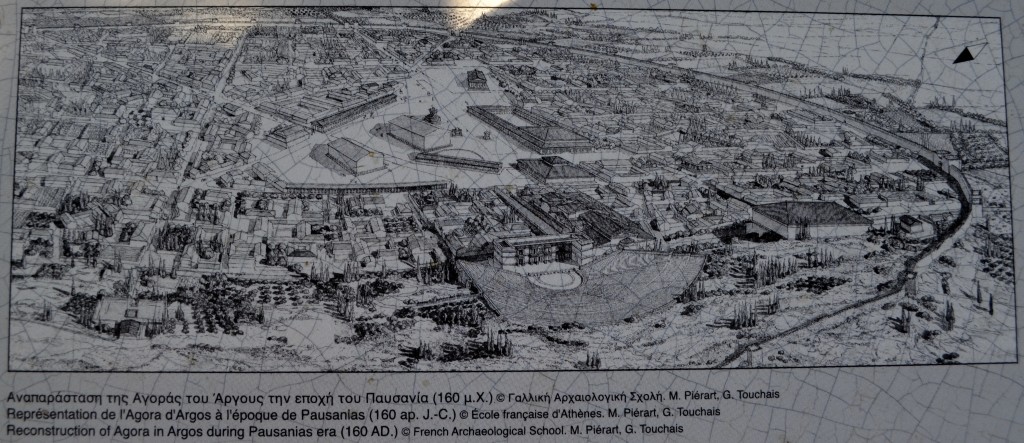

When we think of ancient theatre, however, we cannot help but think first of ancient Greek drama, which was an art form in the lands of the Hellenes long before Romans began producing Latin literature. And like so many other things, the Romans adopted forms of drama from the Greeks as well, especially drama in the form of plays.

Greek ‘New Comedy’ was introduced in Latin in Rome around 240 B.C. by Livius Andonicus and Naevius, and shortly afterward, Greek plays were being adapted by Terence, Caecilus Statius and of course, Plautus, whose early works are the oldest Latin literary works to survive in their entirety. We’ll talk more about the latter later in this blog series. These plays were called fabulae palliatae, or ‘plays in Greek cloaks’.

However, Latin drama had begun to evolve out of this, and soon there emerged the fabulae togatae, or ‘plays in togas’, which were comic plays about Italian life and Italian characters. Sadly, there are no surviving examples of these early Latin comedies.

Surprisingly, by the first century B.C., Roman comic plays pretty much ceased to be written and were replaced by mime which was much more vulgar and thought by many to be of little literary merit.

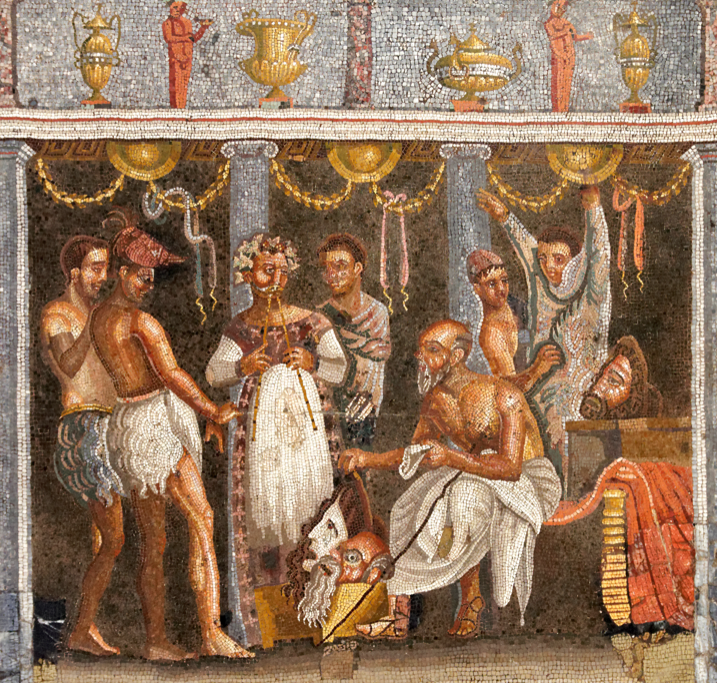

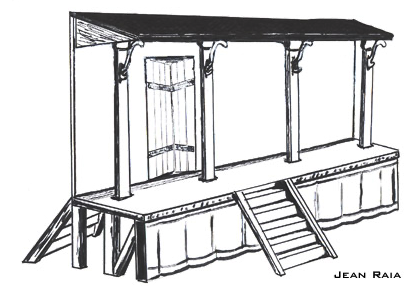

Illustration of Roman mime performance

Other fabulae were introduced by Livius Andronicus, including the fabula crepidata which was a Roman tragedy on a Greek theme, and the fabula praetexta which was a Roman drama based on a historical or legendary theme.

The latter, a form invented by Naevius, gained little popularity in Rome, and by the late Republican era, tragedy in general began to decline. There was a short revival under Augustus, but it did not last, and there are no surviving works of Roman tragedy that come down to us.

It seems the Romans would have leaned more toward Dumb and Dumber than Romeo and Juliet…

One theory about the lack of survival of tragedy in ancient Rome is that under the Empire, it was difficult to choose a safe subject.

But what about actors in ancient Rome, the people who performed before the masses in the streets, on temple steps, or in the great theatres that later adorned cities across the Empire?

Generally, actors were among the lowest on the social scale, the same as gladiators or prostitutes. People enjoyed their performances, and sometimes looked upon them with awe, but they were often kept at a distance for propriety sake. However, some actors were so famous that women, of high and low origin, had affairs with them, not unlike famous gladiators.

This is in contrast somewhat to how it was in ancient Greece where the creation of drama and acting were admired, well-respected.

In the world of ancient Rome, most actors were frowned upon, despite their ability to amuse the people. In truth, the majority of actors were either slaves or freedmen, a very few of which went on to achieve fame, respect, and personal fortune. Most of them likely performed in the lewd mimes favoured by the masses.

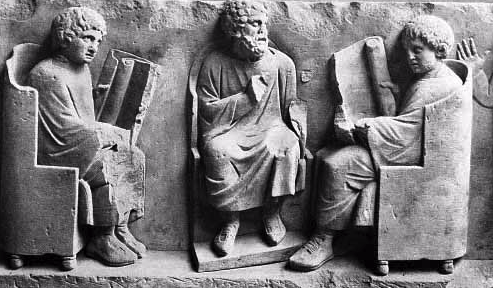

That said, a good pantomime slave actor could cost as much as 700,000 sestercii! And it is believed that many pantomime actors may have received training in dance, poetry, and even mythology, the stories of which they sometimes performed.

A famous Roman actor during the reign of Emperor Augustus, known as Pylades, accumulated so much wealth that he was able to produce his own plays. Despite their low social standing, a few actors could indeed be paid very well. In fact, it came to be such a problem that the Emperor Marcus Aurelius put a legal maximum on actor salaries.

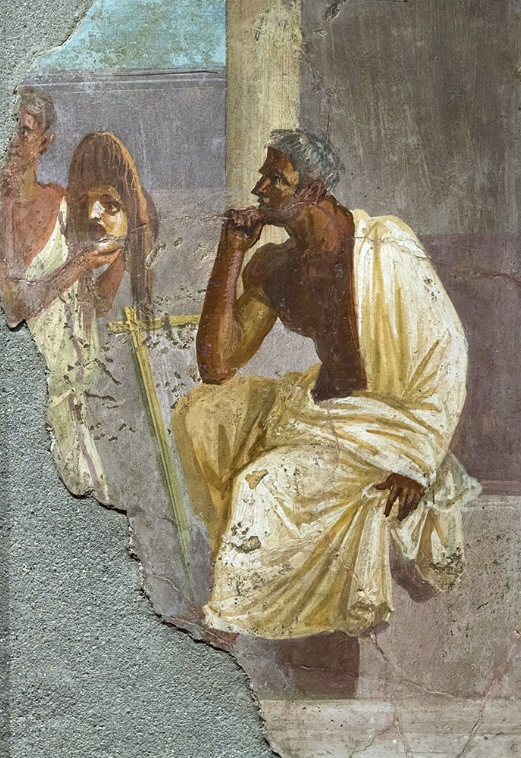

Actor and Mask from a Fresco at Pompeii (Wikimedia Commons)

There were companies of actors who moved about, usually performing at games, or ludi, in Rome and across the Empire. A company of actors, or a grex, was led by the dominus gregis, the leader and owner of the company. This person was likely a freedman who went on to have some success.

Despite the lack of respect for the actors themselves, they did have an association of theatrical authors and actors in ancient Rome known as the Collegium Scribarum Histrionumque whose patron goddess was Minerva. This was perhaps similar to modern organizations such as Actors Equity Association in the US, or the Association of Canadian Cinema Television and Radio Artists (ACTRA).

Acting in Rome was different than it was in the world of ancient Greece. We have already mentioned the general lack of respect toward the acting profession in Rome compared with Greece where there were festivals with prizes such as the Dionysia and Panathenaea at Athens, and even the Pythian Games at Delphi.

However, in ancient Greece, women were strictly barred from performing on stage. It was a man’s world with men performing the roles of female characters. It was seen as dangerous to have a woman on stage.

This carried over into early drama in the Roman world, influenced as it was by Greek tradition. Over time however, women were permitted to perform on Roman stages. At first, their roles were limited to performing in mimes or pantomimes as part of the chorus or as dancers.

Eventually, female actors began to take on greater roles in Roman drama, some of them becoming so famous that they were permitted to perform in the great theatres of Rome and across the Empire.

Such actresses were known as archimimae, or leading ladies, and some of their names have come down to us.

One incredible example is the actress Licinia Eucharis, a Greek-born slave who was so talented that she went on to earn her freedom and be allowed to perform Greek dramas upon the great stages of Rome before the nobles. And this was during the Roman Republic! Quite a feat! Eucharis amassed great wealth from her acting alone.

Another example of an actress who achieved fame as an archimima, this time during the imperial period, was the actress Fabia Arete. She was a freedwoman who was also a diuma, that is, a leading actress who toured and was invited to perform in different places because of her great skill.

Though there are examples of male and, more rarely, female actors achieving great fame, wealth, and respect in ancient Rome, most actors struggled and were relegated to the makeshift wooden stages that they erected in the streets, or upon temple steps, performing lewd mimes for the people who might have tossed a coin their way.

Being an actor was not an easy life, to be sure.

Perhaps it isn’t so different from today?

Sure, there are actors and actresses who achieve fame and accumulate massive amounts of wealth in the modern age, but the reality is that most performers (actors, dancers, musicians, and writers) struggle to make a living.

One thing does seem apparent when it comes to actors in ancient Rome, and that is that this was a time when women in the profession experienced some ascendency, between the strict rules of the ancient Greek theatre world which banned them, and the Medieval Christian era that seemed intent on demonizing them and, once again, banned from the stage.

Despite its shortcomings, the world of ancient Rome seemed to have been a bright spot, in a sense, in the historical timeline. However, when it came to actors, people admired them for their skill and performance, but perhaps mostly from a distance. It was, after all, a world that was foreign to most.

Thank you for reading.

Roman Actors from Fresco at Herculaneum (Wikimedia Commons)

We hope that you’ve enjoyed this short post on drama and actors in ancient Rome. There is a lot more to learn on this subject, so if you want to read more, Professor Edith Hall at Durham University, a leading expert on the subject, has kindly made her books on ancient theatre freely available to the public. You can check them out HERE.

You can also learn more about other types of Roman literature in our popular post Literature in Ancient Rome by CLICKING HERE.

There are a lot more posts coming in The World of Sincerity is a Goddess, so make sure that you are subscribed to the Eagles and Dragons Publishing Newsletter so that you don’t miss any of them. When you subscribe you get the first book in our #1 best selling Eagles and Dragons series for FREE!

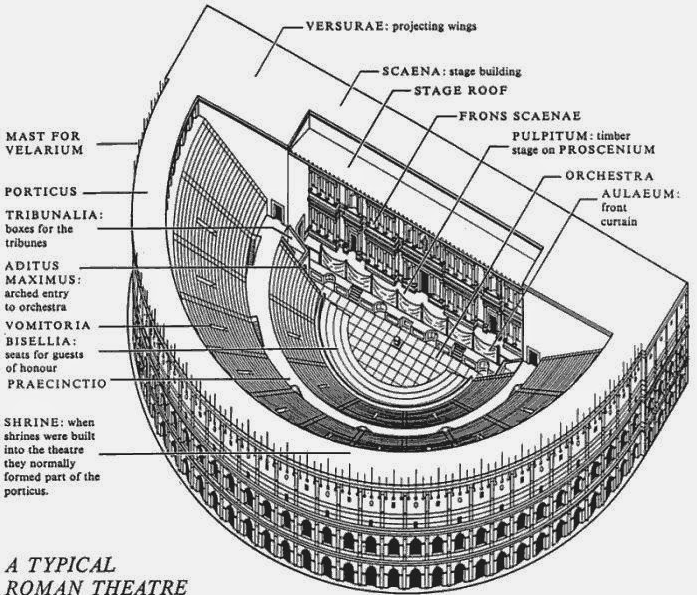

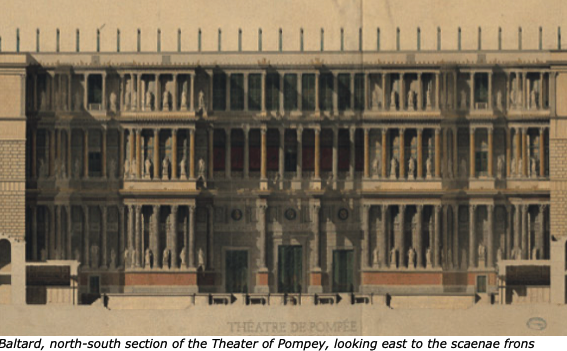

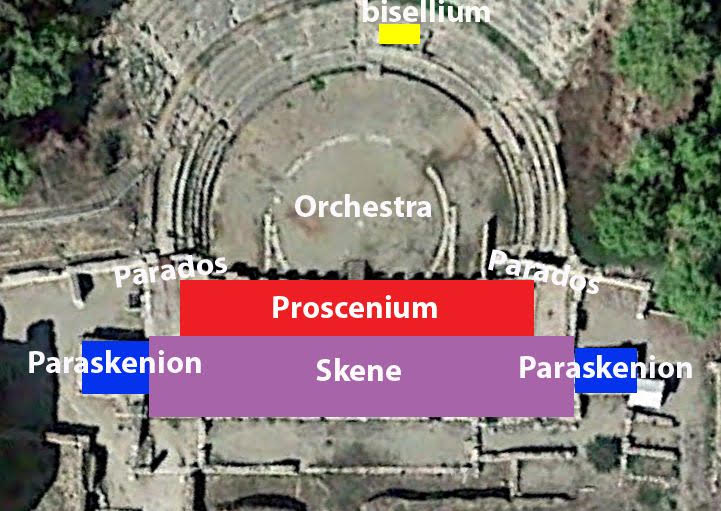

Stay tuned for the next post in this series in which we’ll be looking at theatres in ancient Rome.

Sincerity is a Goddess is now available in ebook, paperback and hardcover from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortar chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy and get ISBN# information for the edition of your choice.

The Etrurian Players are coming! Brace yourselves!