There is one race of men, one race of gods; and from a single mother we both draw our breath. But all allotted power divides us: man is nothing, but for the gods the bronze sky endures as a secure home forever. Nevertheless, we bear some resemblance to the immortals, either in greatness of mind or in nature, although we do not know, by day or by night, towards what goal fortune has written that we should run…

(Pindar, Nemean Ode #6)

For those who love history and archaeology, travelling through Greece is an absolute joy. There is something around every corner, bend in the road, mountain top or valley. History, and its remains, are everywhere.

For me, however, the thing I like the most about this ancient land is how history and mythology are so closely linked, and how they are indelibly tied to the landscape itself.

The Peloponnese is especially rich in this way.

It would take a whole lifetime to visit every historical and archaeological site and landscape that has strong links to the stories of myth and legend from Ancient Greece.

This past summer, we returned to one such place, and I was reminded of how rich and deeply moving this connection between myth, history, and the land can be.

This place is Ancient Nemea.

I first visited Nemea almost twenty years ago, just prior to the 2004 Athens Olympics. At the time, I was unfamiliar with the history and mythology of the site. I was more caught up with this gathering of mysterious ruins set among the undulating vineyards of Nemea’s Wine Country, the largest wine region in Greece where the variety is sometimes known as the ‘Blood of Herakles’.

The myths are as much a part of the Agiorgitiko wine as are the fragrant aromas of raspberry or cherry.

Returning to the site in 2023, I explored the site with a great deal more knowledge of what I was looking at, but also with an awareness of the poignant reason for the creation of the site and the Nemean Games, one of the four Crown Games of Ancient Greece, which were held here.

First, a bit about the myths…

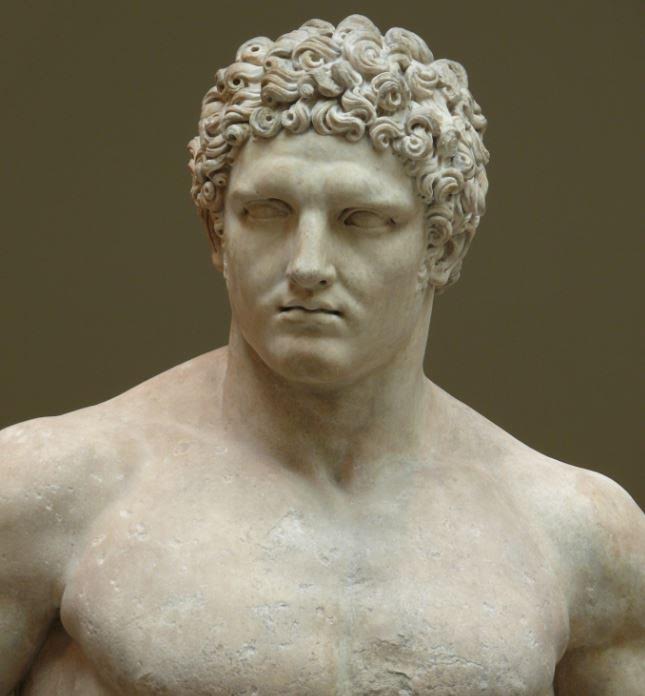

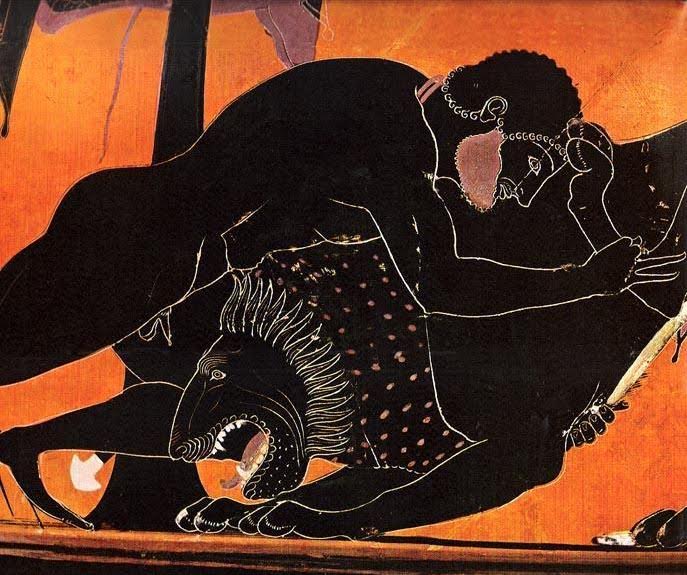

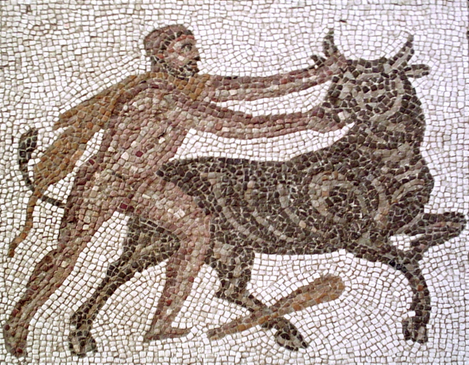

Perhaps the most famous myth related to Nemea is in relation to the first labour of Herakles in which the hero defeated the Nemean Lion. It’s a fantastic and exciting myth, but the Nemean Games were not started in honour of Herakles’ great labour.

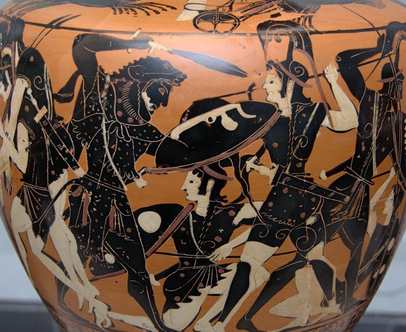

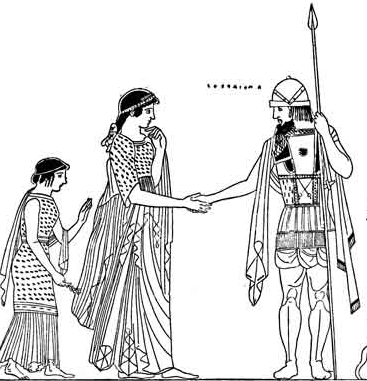

In legend, the Nemean Games are related to the ‘Seven Against Thebes’, the group of warriors who went with Polynices to take back Thebes from his brother, Eteocles. On their way to Thebes, the Seven stopped in Nemea where King Lykourgos ruled with his queen, Eurydike.

The king and queen had a newborn son named Opheltes, whom they were told by the Oracle at Delphi that they could not let touch the ground until he could walk.

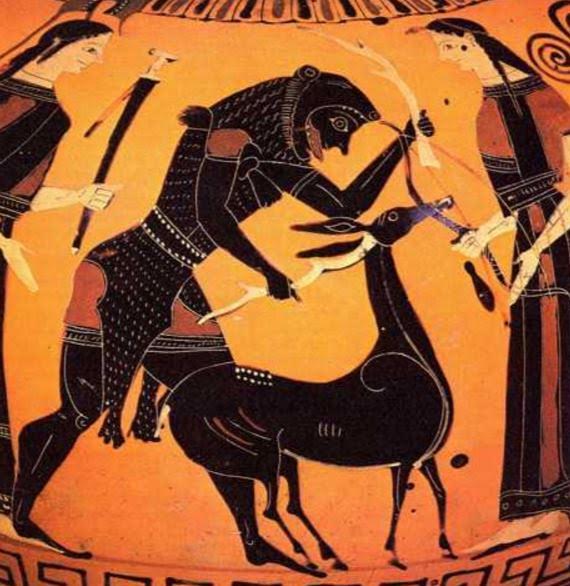

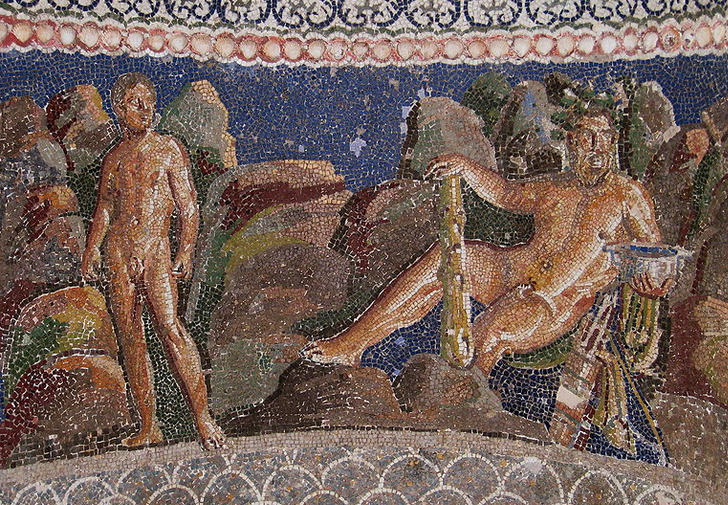

However, one day, the baby’s nurse, Hypsipyle, was walking with the baby when the Seven stopped in Nemea. The Seven asked where the nearest well was, and so Hypsipyle put the baby Opheltes down on a bed of wild celery while she took the generals to the well.

The baby was set upon the ground in contradiction of the Oracle of Delphi’s warning, and so a snake came along and killed the child.

The Seven saw this as a bad omen and sought to honour the soul of the slain child, and propitiate the Gods by holding funeral games on site.

Thus were the Nemean Games born as funeral games for the deceased child, Opheltes.

The victory crown for the Nemean Games, was a crown of wild celery.

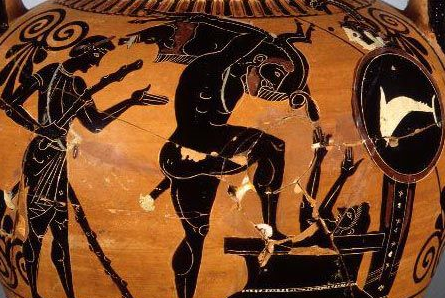

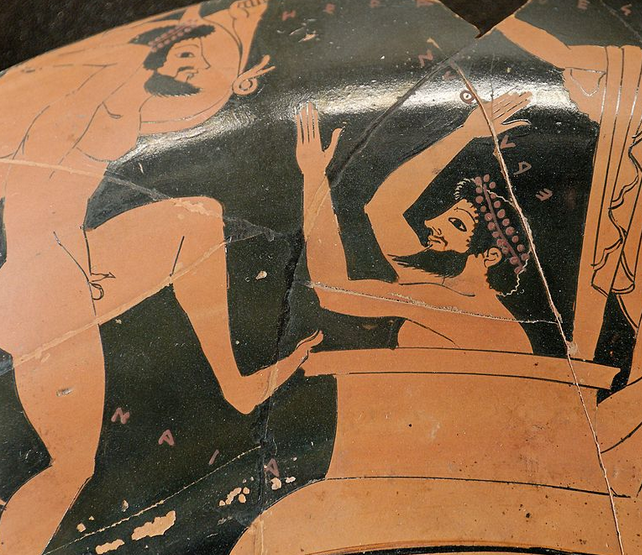

The slaying of the Opheltes by the serpent

The first historical games at Nemea were held in 573 B.C., and they took place every two years. There was no settlement at Nemea, and the games were most often under the auspices of Argos, moving to that ancient city to the south for long stretches of time, except during the period of Macedonian hegemony.

The sanctuary at Nemea was important in the ancient world, but somehow experienced more neglect than others when the Games were moved to Argos. Pausanias, in his second century A.D. tour of Greece, describes the run-down ruins of the site during the Roman period:

In Nemea there is a temple of Zeus Nemeios worth visiting, although the roof has collapsed and there is no longer any statue. Around the temple is a sacred cypress grove. Here was Opheltes, put on the grass by his wet-nurse, killed by the snake, according to the story. The inhabitants of Argos sacrifice to Zeus also in Nemea and choose a priest of Zeus Nemeios. They organize a running contest for men in armour at the festival of the Winter Nemea. So there is the grave of Opheltes, with a stone enclosure around it and inside the enclosure altars. There is also a tumulus as a monument for Lykourgos, the father of Opheltes.

(Pausanias II 15, 2-3)

The Temple of Zeus at Nemea with the great Altar of Zeus in the foreground

Unlike the sanctuary at Ancient Olympia, the archaeological site of Nemea is quiet and uncrowded. You can roam at will where you like without running into any other tourists. It is almost a meditation to visit this place, and that’s good, for the air is heavy with tragedy and toil, and the songs of victory.

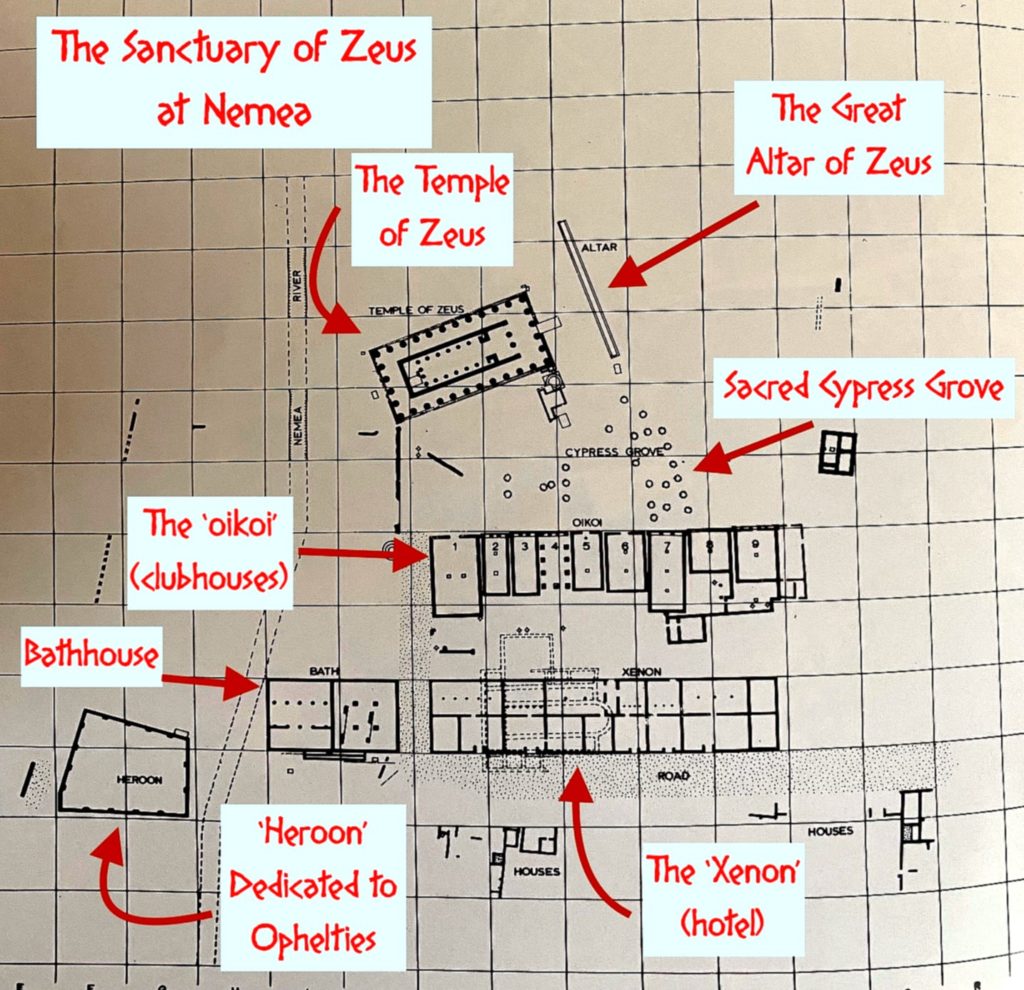

The archaeological site is actually two different sites: the Sanctuary of Zeus, and the Ancient Stadium.

The main site, the Sanctuary of Zeus, where the wonderful museum is located, includes the remains of houses, baths, and a hero shrine or heroon dedicated to the child, Opheltes. It also includes the ruins of the xenon, a sort of ancient hotel for visitors or participants in the Games, and a series of nine oikoi, or ‘clubhouses’ sponsored by specific city-states to house their athletes and coaches during the Games.

The most impressive part of the Nemean sanctuary, however, is the temple of Nemean Zeus which was built c.330 B.C.

The lovingly restored ruins of this temple are truly inspiring and, unlike other sites such as the Parthenon, you can walk through the temple to get a better sense of its scale and its magic. Uniquely, the temple contains the remains of a sunken crypt accessed through the cella, or inner chamber. It is believed the crypt was either used as the site of an oracle, or as a treasury for the sanctuary.

On the east side of the temple is another feature that is unique to Nemea, and Isthmia (an altar to Poseidon), and that is a very long altar to Zeus where athletes and trainers swore their oaths and made sacrifices prior to the competitions. This altar dates to the fifth century B.C.

When we visited the site this time, we were armed with a 4K video camera and so, rather than tell you about all the minute details of the sanctuary, we can now show you in the video Nemea – A Tour of the Sanctuary of Zeus…

After roaming the Sanctuary of Zeus, we got in the car and drove the very short distance down the road to the second part of the archaeological site of Ancient Nemea, the Stadium.

This site is much smaller than the sanctuary, taking less time to visit, but it is well worth it.

Participants in the Nemean Games would have sworn their oaths and made their offerings to Zeus at the long altar in the sanctuary before processing to the stadium for the actual athletic competitions.

Nemea’s stadium is smaller than Olympia’s, but it’s still substantial, as it should have been for a location of one of the four Crown Games. It could seat up to 40,000 spectators in its day on the roughly hewn stone seats and embankments.

There are some fascinating remains to be seen at Nemea’s stadium, including the starting line and its mechanism, as well as the channels that flow around the stadium, once fed by mountain springs, so that athletes and spectators could drink and stay hydrated during the competitions.

The apodyterion, or ‘locker room’ where athletes prepared