Mycenae…

The name conjures something deep inside, something out of myth and legend. There is a feeling of mystery about the name, of power, and perhaps of dread.

How is that? It’s just a name after all, isn’t it?

Not really. It’s much more than that.

Mycenae.

It echoes in the mind, in the memory of time. For me, it is something of a sign post in far away antiquity. It’s not just a place, but also a culture, a people… It is a warlike period that stands out in the vast Bronze Age, between the Age of Heroes and the Archaic period.

Mycenae itself, the place, is a symbol of a brutal time, long ago, that continues to captivate our imaginations, the same way that it has done for our ancestors since then.

Mycenaean Warriors

A barrage of names comes to mind when I think of Mycenae, like so many barbed bronze arrows raining down in the midst of a battle – Atreus, Agamemnon, Achilles, Menelaus, Helen, Clytemnestra, Electra, Orestes and all the heroes of the Trojan War. I think of Homer whose epic Iliada immortalized them all, and even of Alexander the Great who is said to have slept with a copy of that epic beneath his pillow.

Before the summer of 2023, the last time I had visited Mycenae, that dread cyclopean-walled palace whose corridors echoed with war and murder, was on a warm day in March over twenty-years ago.

On my first visit, it was springtime, the ruins surrounded by wild flowers.

I had been back to Greece frequently since then, of course, visiting other archaeological sites, writing about them in my novels and articles, but in all that time, I avoided Mycenae.

I don’t know why exactly, but my natural tendency was to give it a wide berth, to be near it, but only orbiting it. I avoided the tourist assault upon the great ‘Lion Gate’, and the blazing heat that one experiences when visiting it in high summer.

I felt like returning to Mycenae too soon was like returning to the scene of a crime. There is a lingering sadness, a sense of loss about the place that is difficult to describe.

As the epics teach us, however, life is beautiful, and terrible, and fleeting. Since my first visit long ago, time seemed to have flowed more quickly than I would have wished when I as a child.

The citadel of Mycenae as seen from the approach on the road from the modern village of Mykines.

When I first visited Mycenae I was much younger, a little naive, and definitely more idealistic. I was just setting out for my own battles beneath the walls of a distant, metaphorical Troy.

Older now, and having endured my own toils, I wondered if I was ready to return to the flattened halls of Mycenae with a perspective that is afforded by age and experience.

With my wife, and our own children bearing the same excitement and idealism I once possessed, the decision was taken. We would make our way to Mycenae.

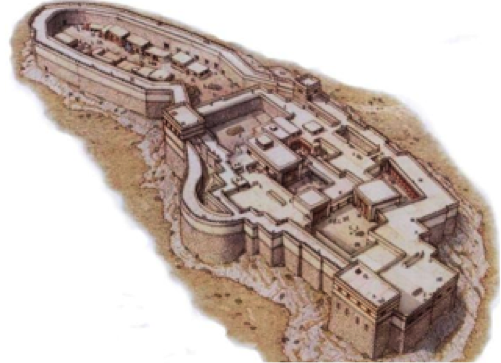

Aerial view of the archaeological site

Though it is mostly known as the fortress of King Agamemnon, who led the Greek army at Troy, Mycenae has a long, rich and mythical past.

Briefly then…

Although it is believed that there has been habitation on the acropolis of Mycenae since roughly c. 2500 B.C.E, legend has it that Mycenae was originally founded by Perseus, the son of Zeus and Danae, and first King of Mycenae. Perseus is said to have used the legendary Cyclops to build Mycenae’s great walls some time in the first half of the 14th century B.C.E.

For a long time, Mycenae thrived under the descendants of Perseus, including Eurystheus for whom Herakles performed his famed Labours. After Eurystheus was killed in battle against the children of Herakles and the Athenians, the people of Mycenae chose Atreus, the son of Pelops and Hippodameia to rule them.

Many years of prosperity and greatness followed under the Atreidai dynasty, beginning with King Atreus, and then under his son, King Agamemnon, who was said to be the greatest king in Greece, ruling over the plains of Argos to the south, and the entire northeastern Peloponnese, including Corinth, sometime between 1220-1190.

Mycenae was at the heart of this world, and one of the most important cultural and political centres during Greece’s Bronze Age until its destruction toward the end of the 12th century B.C.E.

It was (and remains) a place where the history of the curse of the Atreidai, written about by ancient playwrights, still echoes about the landscape, and behind the mass of Mycenae’s great Cyclopean walls.

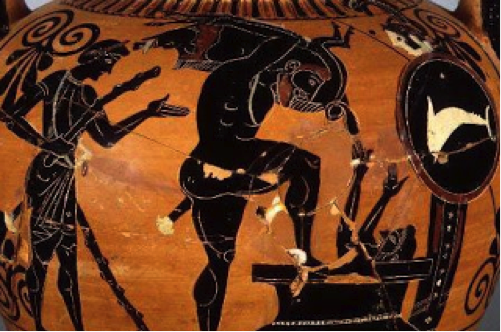

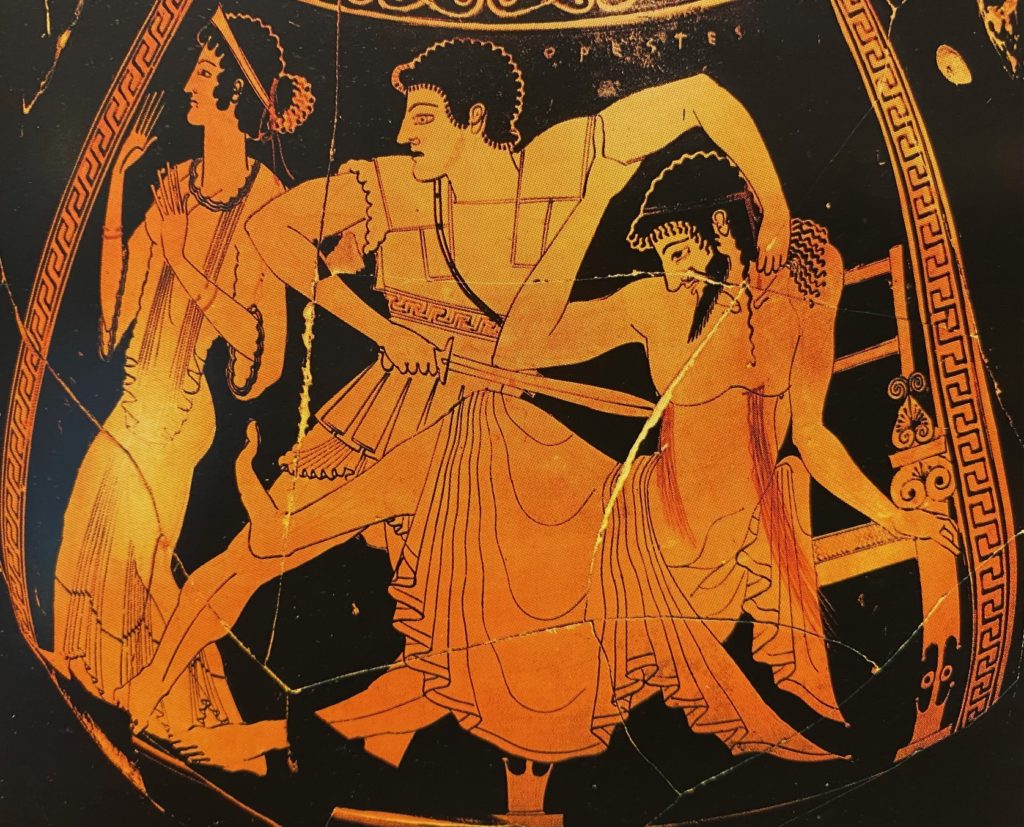

Ajax, Agamemnon, and Odysseus

The later traveller Pausanias, who visited Mycenae in the middle of the second century C.E. is thought to be the last ancient author to write about Mycenae:

There still remain, however, parts of the city wall, including the gate, upon which stand lions. These, too, are said to be the work of the Cyclopes, who made for Proetus the wall at Tiryns.

In the ruins of Mycenae is a fountain called Persea; there are also underground chambers of Atreus and his children, in which were stored their treasures. There is the grave of Atreus, along with the graves of such as returned with Agamemnon from Troy, and were murdered by Aegisthus after he had given them a banquet. As for the tomb of Cassandra, it is claimed by the Lacedaemonians who dwell around Amyclae. Agamemnon has his tomb, and so has Eurymedon the charioteer, while another is shared by Teledamus and Pelops, twin sons, they say, of Cassandra, whom while yet babies Aegisthus slew after their parents. Electra has her tomb, for Orestes married her to Pylades. Hellanicus adds that the children of Pylades by Electra were Medon and Strophius. Clytemnestra and Aegisthus were buried at some little distance from the wall. They were thought unworthy of a place within it, where lay Agamemnon himself and those who were murdered with him.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.16)

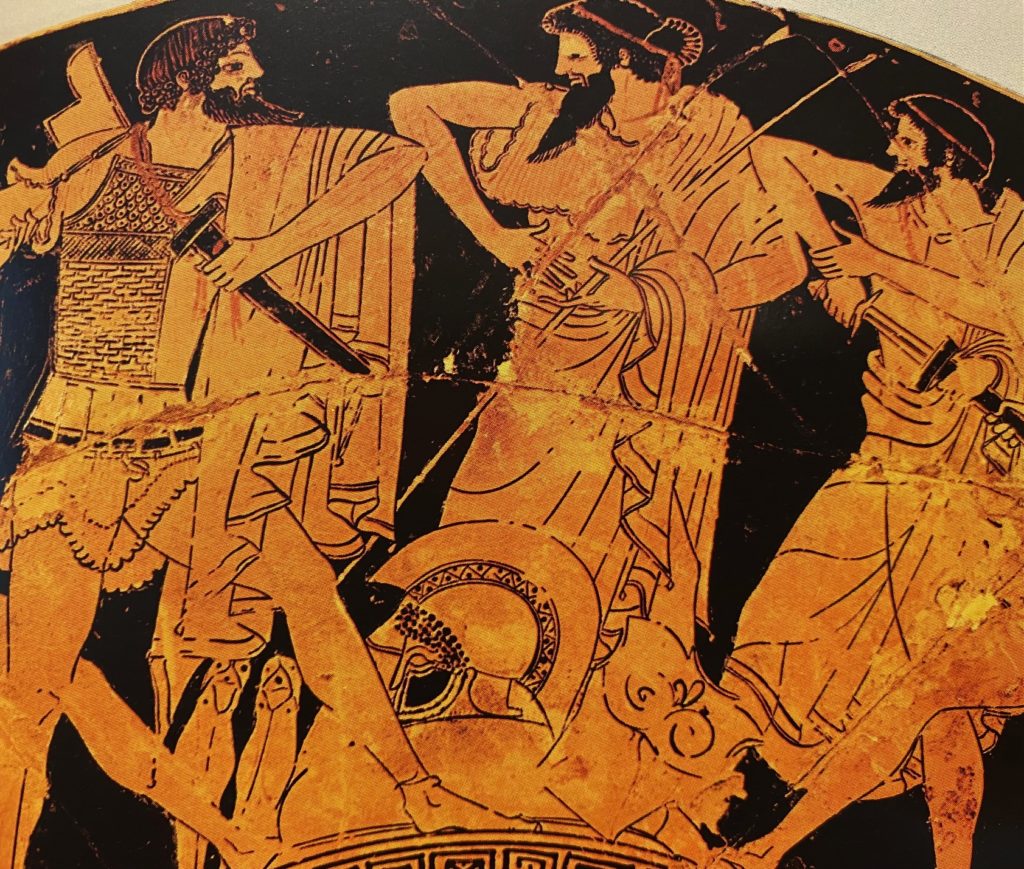

The Murder of Aegisthus by Orestes

When we made the decision to visit Mycenae again, these are the stories and people whom I was thinking about the night before as we ate dinner on a terrace beneath the stars.

The night was hot and calm, those ancient mountains black against the purple and indigo night sky pocked with stars. From our hotel in the modern village of Mykines, I was constantly aware of the citadel up the hill, surrounded by the tombs of legends. As I sipped cool wine from a glass and listened to the bark of a distant dog, or the screech of a fox, I wondered if, from the palace of Mycenae itself, Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, Orestes and Electra, or even a young Iphigenia, had seen what I was seeing.

Had those people of myth and legend looked from their palace walls to see the flickering of fires atop the walls of Argos across the plain? Had they travelled to make offerings to Hera at her sanctuary down the mountainside on the way to Tiryns? Did they enjoy the slash of brilliant blue afforded by the Gulf of Argos that lit the distance on a clear day? Did they too savour the wine, oil, and fruit of that very same land as I was in that moment?

It that ancient landscape laced with history and myth, I felt certain that they had done all of that.

The myths are everywhere in the Argolid.

Dinnertime view from the village of Mycenae to the south from the terrace of our hotel, La Petite Planète.

The next morning we rose early with the crowing of a nearby cock and the barking of a dog, had a hearty breakfast, and drove the short kilometre up the road to the archaeological site in the hopes of beating the crowds.

It was just 8 a.m. and yet the car park was already half-full, the sun beating down, priming us for yet another day of 45 degrees Celsius.

While most of the sweating hordes of tourists went first to the museum, or a stop at the loos, we marched directly up the curving path toward the high walls of Mycenae and found ourselves with a blessedly unobstructed view of the famed ‘Lion Gate’ of the citadel.

The ‘Lion Gate’ of Mycenae

It took my breath away, though I had been before, and seen it countless times in books while doing research.

To stand in the shadow of those Cyclopean walls, before that monumental gate, to imagine Mycenaean warriors with their spears and boar’s tusk helmets staring down at you, is an experience unlike any other.

The pictures don’t do it justice.

How many kings and warriors had walked through that gate? How many chariots with bronze warriors had driven up to it? How many Trojan slaves, like Cassandra, had been forced within that stoney curtain of unimaginable size?

After taking it in, we filmed what we needed to, and pressed forward to begin our exploration of the vast ruins.

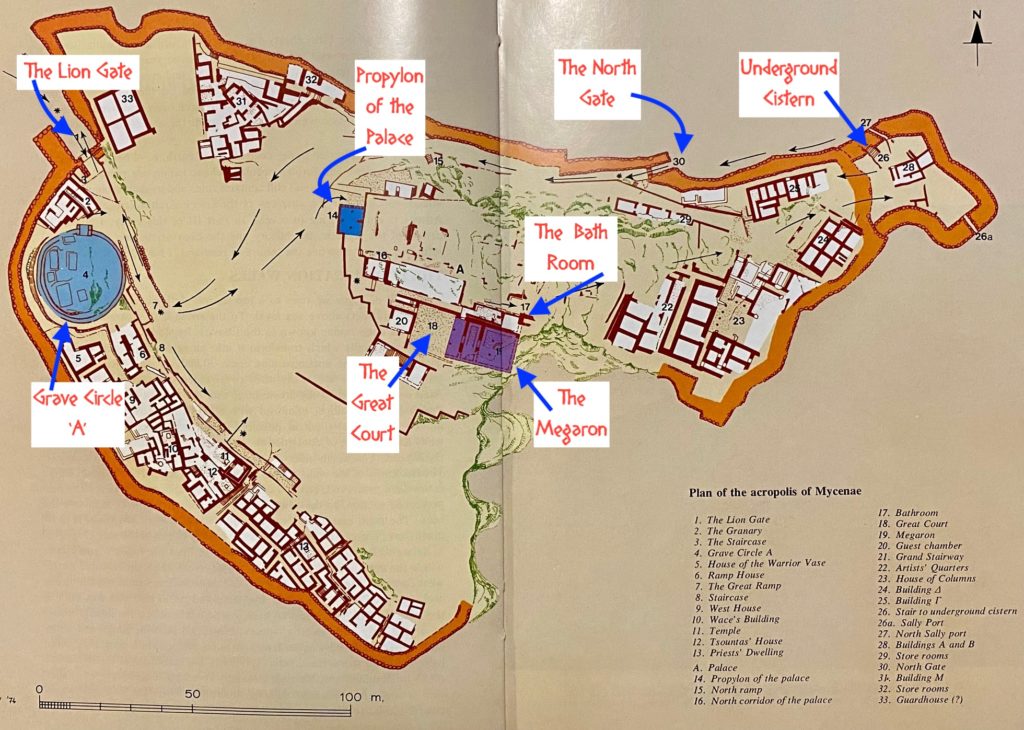

It can be overwhelming to visit a site as big as Mycenae, especially if you don’t know what you’re looking at.

Fortunately, that was not us. It helps to be familiar with the site and to come armed with a proper map such as we were. There is no grid pattern such as one might find in ancient Roman settlements. Mycenae is spread out over the top of a high rock, and surrounded by higher mountains with deep chasms on the north and south sides, and and rocky cliffs that fall away to plains covered in olive groves and fruit trees in the valleys to the northwest and southwest toward Argos and the sea.

Inside the Lion Gate, and past the guardhouse on the left, we made directly for one of the most famous locations within the citadel: Grave Circle ‘A’.

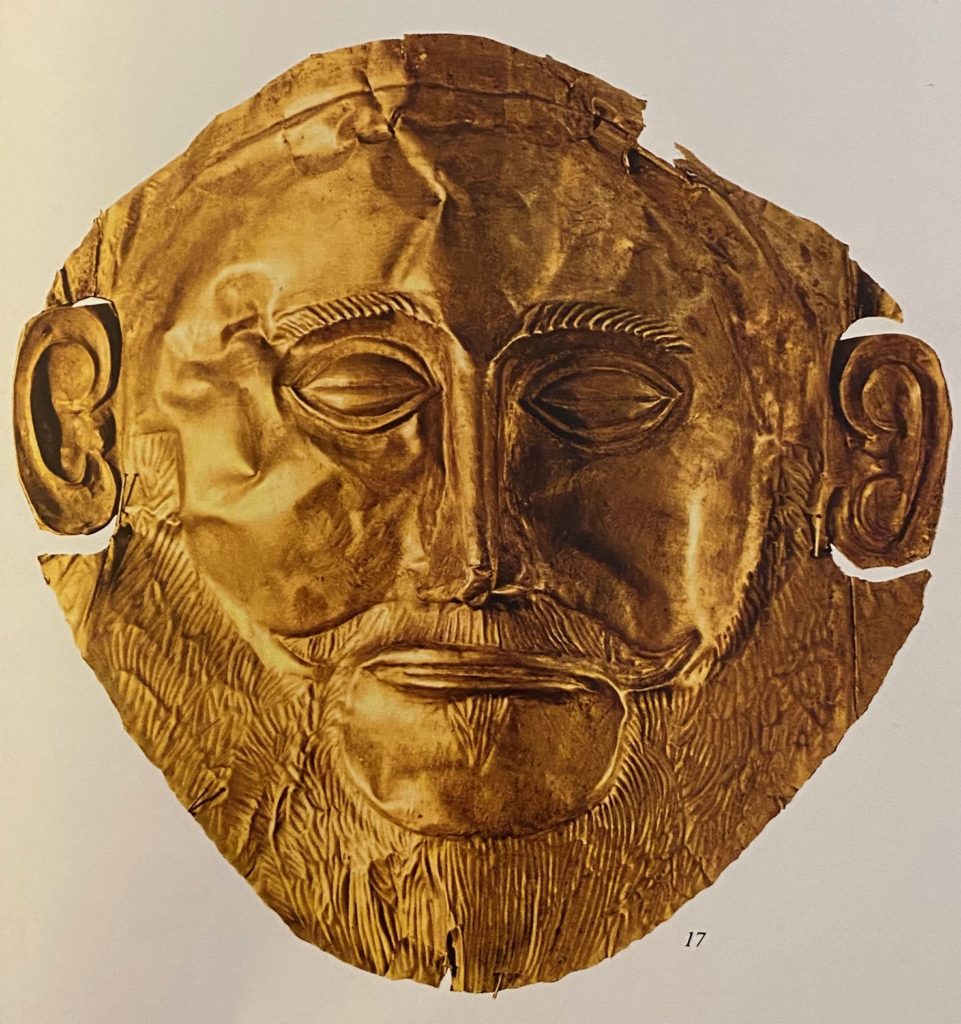

This vast, deep circle surrounded by upright slabs was the royal cemetery, intended to impress those who entered the fortress, and to honour the dead rulers of Mycenae. This is where Heinrich Schliemann, the German archaeologist who discovered Troy, found the six grave shafts in 1876 and the remains of nineteen skeletons, including eight men, nine women, and two children. They were buried with riches, gifts, food and furnishings for their journey to the Underworld.

Bronze daggers found in ‘Grave Circle A’

It is also here that Schliemann and Greek archaeologist, Panagiotis A. Stamatakis, discovered among the grave goods some of the most famous artifacts from the period, including the bronze swords and daggers, golden goblets and cups, five golden death masks and other objects with elaborate gold leaf designs, amber and more.

Though Schliemann was determined that one of the graves and the golden death mask within it, belonged to Agamemnon, it was later determined that these burials predated that period by a few hundred years.

Still, the beauty of those finds is unmistakable, and the site unlike anything else.

Site of the Royal Tombs in Grave Circle ‘A’

After visiting Grave Circle ‘A’, most people will begin the trek to the upper acropolis where the palace is located, but before one does, it’s a good idea to continue ahead to view the southern sector of the citadel where there was a temple and the dwellings of the priests of Mycenae. From here, beneath the shade of a lone fig tree, one can look out across the plain to the distant mountains and sea.

I stood there for a few moments, the air white hot and dusty, the light blinding as I looked over my map to see my route up the stairs and the path that leads to the propylon of the palace.

View from the ‘Great Court’ and propylon of the megaron of the palace toward the Argolic Gulf and Argos across the plain.

On my first visit to Mycenae I didn’t really know what I was looking at. It was all quite overwhelming. Of course I knew about the Trojan War, and something of Agamemnon, but the importance of that place, those stories and characters in the identity of the west, and corpus of literature of western civilization, was still unknown to me.

However, on this visit, as I passed through the propylon, the grand entrance to the palace, I knew what lay ahead, knew that I was walking in the footsteps of legends.

The pathway leads up until, on your right, you come to a series of rooms that were the beating heart of the palace. There is a guest chamber where dignitaries would have stayed, and the ‘Great Court’ where courtiers and guests would have waited for an audience with the king. And then from the ‘Great Court’, you can see another propylon leading to what was the megaron of Mycenae, the throne room.

Artist impression of the megaron of Mycenae

On my first visit to Mycenae, I was able to walk though the ‘Great Court’ unimpeded, forward through the propylon, and on into the megaron itself. I remembered looking at the outline of a great circle in the middle where the hearth fire was supposed to have been located.

Sadly, today, the ‘Great Court’ and megaron are closed off, so I could only admire them from the path higher up. There is also now a small shelter over the location of the hearth fire, shielding it from the elements, and also from the prying eyes of tourists.

The megaron of Mycenae today. Note the roof covering the site of the hearth fire in the centre.

Perhaps one of the most interesting parts of the site, that may be linked to one of the bloodier episodes purported to have taken place at Mycenae, is the room adjacent to the throne room. This long oddly shaped room that has some low walls is thought to be the bathroom where, as legend has it, Clytemnestra murdered her husband, Agamemnon, as he bathed.

The Murder of Agamemnon, painting by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1817) – though not in the bath in this representation.

Having taken in the heart of the site, it is worth crossing the path and climbing up the ruins on the other side for a magnificent 360 degree view of the site and surrounding countryside. There was a later temple on this high spot, believed to be dedicated to either Hera or Athena. The temple is long gone sadly, but it is still worth standing there and taking it all in.

That done, we proceeded down the path that led to the eastern quarter of the citadel where it is believed there were artists’ quarters, store rooms, and other structures that formed part of the palace’s east wing.

Stairs leading down to the cistern of Mycenae

If you pass this eastern area of the citadel and proceed to the end of the path, you will find low ruins of buildings flanked by an arched ‘sally port’ on the right, and to the left the north ‘sally port’ beside which is the arched tunnel that leads down a staircase to the underground cistern of Mycenae. It is definitely worth having a look down there, but if you do go, bring a good flashlight so that you can properly peer into the darkness below.

The ‘North Gate’ of Mycenae’s citadel

After we emerged from the cool dark of the cistern, we exited the citadel at the North ‘Sally Port’ and took a path along the outside of the north wall to re-enter the citadel at the sturdy north gate of the acropolis. From here, the cliff falls away to olive groves and the site museum down the hill, built to look like the palace itself might have done.

Beautiful views are a constant when one visits Mycenae. You just have to remember to look up.

From there, the path leads along the inside of the north wall back to the guardhouse and the inside of the ‘Lion Gate’.

When we arrived back at the main gate, it was to a great invasion of tourists, all of them crowded beneath the monumental sculpture which they admired, taking advantage of the shade afforded by those magnificent Cyclopean walls.

I was grateful we had come early, and felt blessed to have had a quiet moment alone with the Lions of Mycenae.

One of the golden death masks found in Grave Circle ‘A’ at Mycenae. This one was believed by Schliemann to be the ‘face of Agamemnon’

Admittedly, the heat had been so intense, my mind so taken up with the site itself, that the museum which we visited afterward, was a bit of a blur. The most impressive finds from Mycenae are in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, but there is still a lot to see in the site museum at Mycenae itself. Once you have rested, it is definitely worth a look.

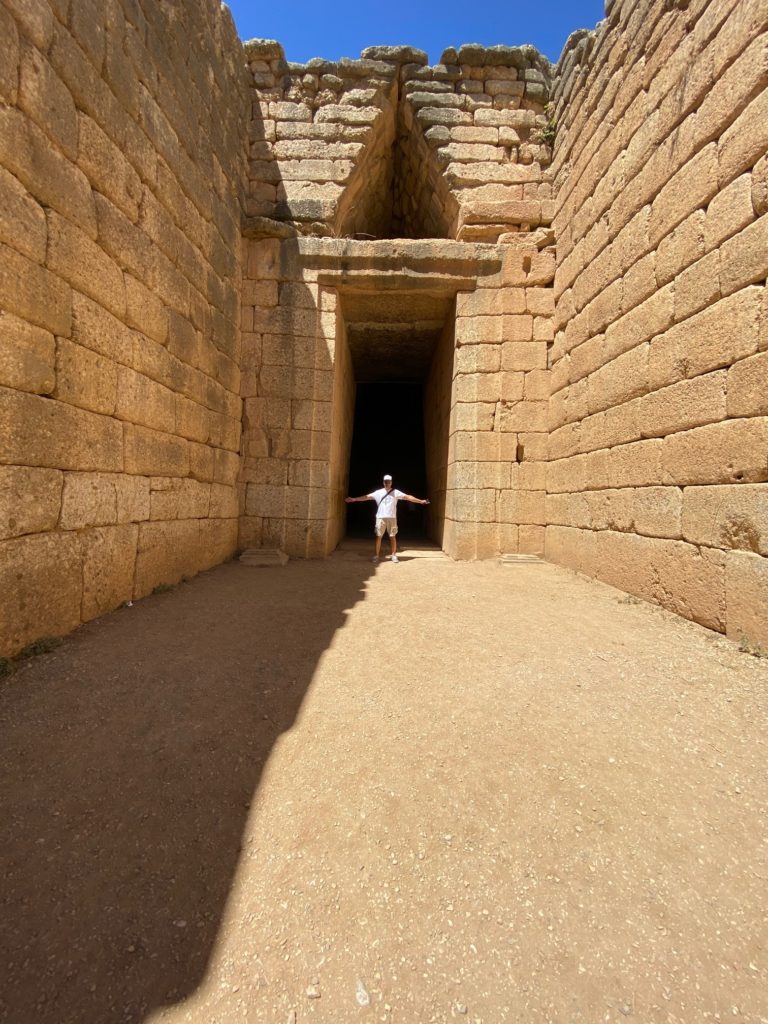

There is another aspect to my return to Mycenae that I have not covered, and that is my exploration of the great tombs that surround it.

Mycenae, it seems to me, is surrounded by the Dead, and after a brief rest, we went in search of them.

But that is a story for next time…

Stayed tuned for the next post on the ‘Tombs of Mycenae’

If you are interested in visiting Mycenae for yourself, be sure to check out the deals that are available from Eagles and Dragons Publishing’s subsidiary, Ancient World Travel here:

https://www.ancientworldtravel.net/travel-resources-1

Check out our specially-curated deals on visits, tours (many from Athens) and tickets to Ancient Mycenae by CLICKING HERE.

If you want to see the magnificent collection of artifacts from Mycenae, you can get affordable tickets to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens by CLICKING HERE.

Also, read the review of La Petite Planète, a lovely hotel (with an amazing terrace for dinner!) in the village of Mycenae where you can stay here:

https://www.ancientworldtravel.net/post/hotel-review-la-petite-planète-a-warm-welcome-in-the-shadow-of-ancient-mycenae

Lastly, check out the video of our site visit to Mycenae on the Eagles and Dragons Publishing YouTube and Rumble channels.

Walk with us through the ruins of this legendary site!

Stay tuned for our next post about the Tombs of Mycenae…

Thank you for watching, and thank you for reading!