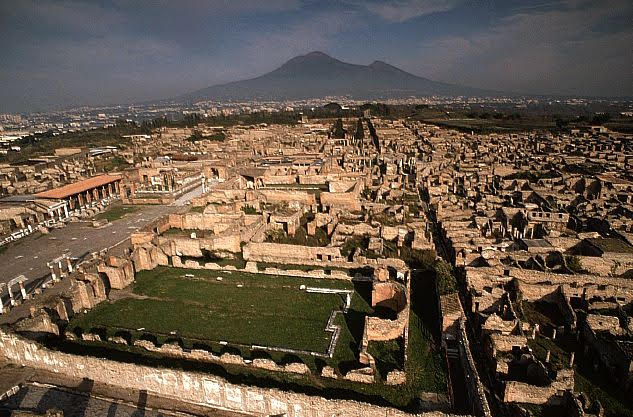

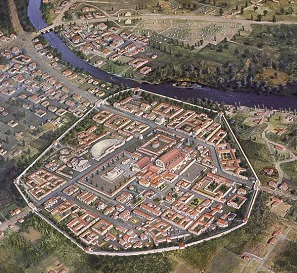

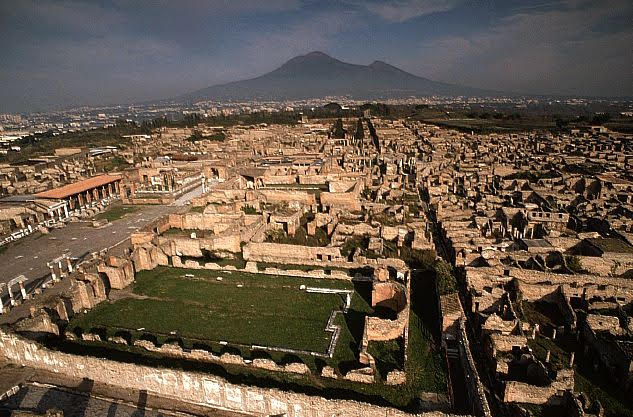

When it comes to the Roman Empire, few things fascinate us as much as the destruction of Pompeii and the host of archaeological treasures that have been preserved by Mt. Vesuvius’s pyroclastic eruption.

We’ve all read the books, and seen the documentaries, artistic recreations, and recent film that have attempted to bring this ancient city back to life. They help us to understand, and live safely through, one of the greatest cataclysms in Roman history.

Pompeii movie poster

When I think of Pompeii, some of the first things that come to mind are the frescoes of the newly-restored Villa of Mysteries, the Temple of Apollo in the forum, or the Great Lupanar, Pompeii’s largest brothel. The artistic and architectural treasures that have been preserved by the ash are myriad.

Fresco from Pompeii’s Villa of Mysteries

However, it is the people of Pompeii that haunt me most.

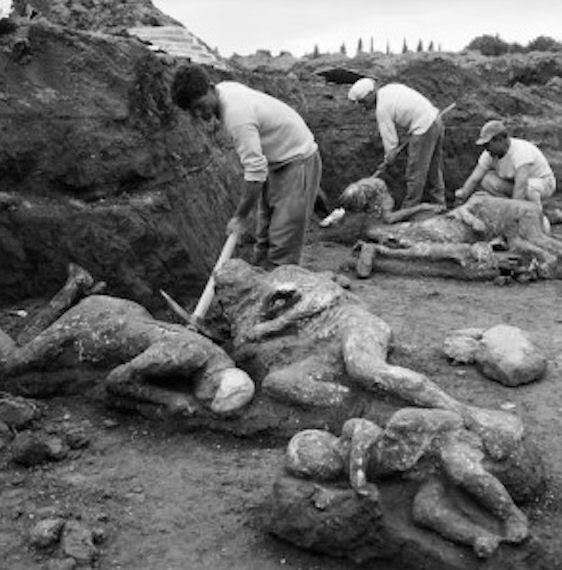

Unlike neighbouring Herculaneum, where the populace seems to have escaped, Pompeii’s ruins were littered with human remains.

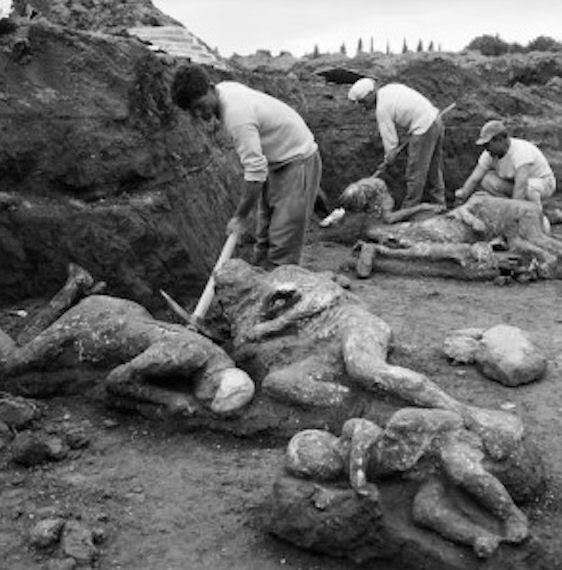

Many of you will recognize the shades of these fallen Pompeians from the plaster casts that now represent them.

In 1863 the head archaeologist at Pompeii, Giuseppe Fiorelli, noticed unusual voids in the ash layer of the site. He realized that these voids contained human remains, and so devised the technique of injecting plaster into the spaces to recreate the forms of Vesuvius’s victims.

A Pompeian Family

These are the most haunting artifacts Pompeii has to offer: its people.

Today I have something very special to share with you.

My friend and fellow author, Jenn Blair, recently had a triad of poems about events that took place on February 3rd, 1863 published in The Cossack Literary Journal.

The first of these poems is entitled ‘Pompeii’, and the first time I read it I knew I had to share it with you.

It takes us back in time to the excavations of Pompeii and gives us an intimate glimpse into the thoughts and feelings of Guiseppe Fiorelli:

February 3, 1863

Pompeii

The wells went dry. But they did not suspect, even then,

walking, to prayers, to market – swimming along in

strange morning light whose quality was already

changing. I kneel down and fish out the bones carefully,

with slender tongs, before pouring gesso in the hardened ash.

Some sculpt out of the air, but I persist in believing there are

forms already present, absences which are too telling-

a chance to become intimate with curdled hands or

even the downcast eyelashes of the woman and man

and child long ago cast down. Perhaps they will have

amulets and goddesses in arm, or perhaps they will

hold nothing, except themselves, that one last possession,

all limbs pulled in as if to ask the gods for respite now

that their small bodies inhabit even tighter boundaries.

Frescoes, vases, temples, carbonized loaves of bread: important.

But enough of artifacts. I want to see a living face.

Uncovering the Dead of Pompeii

I love this poem.

Having worked as an archaeologist, I remember getting excited about ancient people’s rubbish, about broken pots, coins, and crushed decorations, but in reading Jenn Blair’s poem above, I imagine the great sadness that must have descended on Fiorelli as he unearthed his plaster casts of the dead.

Uncovering the people of Pompeii was not like discovering an intentional burial, where the dead are at peace, surrounded by prized grave goods.

In Pompeii, when the bodies were unearthed, they appeared in pain and despair, “all limbs pulled in as if to ask the gods for respite…”

Pompeii and its disaster will, I feel sure, fascinate and haunt us for generations to come.

Vintage Postcard of Pompeii

Thank you for reading.

Jenn Blair

Jenn Blair has published work in the Berkley Poetry Review, Copper Nickel, Superstition Review, Kestrel, Cold Mountain Review, Blood Orange Review, Tusculum Review, New Plains Review, Tidal Basin Review, Southloop Review, Clockhouse Review, and The Newtowner among others. Her prose manuscript Human Voices was a finalist for Texas Review Press’s 2014 George Garrett Prize. She teaches at the University of Georgia and lives with her family in Winterville, GA.

Be sure to check out Jenn’s poetry chap books too at the links below: