Roman Army

The World of the Carpathian Interlude – Part II : Roman Weapons

Welcome to Part II in The World of the Carpathian Interlude.

In this historical horror series, there are several battle sequences against not only human foes, but also against the evil forces of undead and unnatural creatures.

In such situations, having the right weapons is one of the only ways to survive, that and having your gods on your side…

When Optio Gaius Justus Vitalis and his men set out to confront legions of undead in a dark valley of the Carpathian mountains, there is one thing that really enables the Romans to hold their own: weapons.

Let’s look at the weapons of a Roman soldier.

The Roman army was one of the most disciplined, well-organized and well-armed fighting forces of the ancient world, and their weaponry evolved over time as they adopted the best from each nation they conquered.

In The Carpathian Interlude, I have tried to use the Latin names for all the weapons and articles of clothing. However, for those of you who may not be familiar with the world and weapons of ancient Rome, here is a crash course in case you ever find yourself facing down legions of undead.

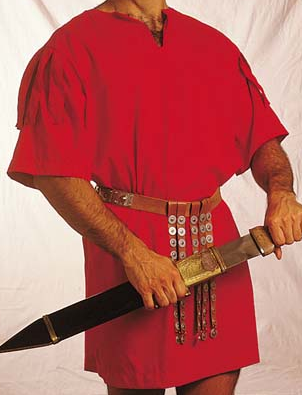

First, and most importantly, is the gladius. This is the Roman soldier’s (legionary’s) sword. The word ‘gladiator’ is derived from this word. This weapon has been called the ‘meat-cleaver’ of the ancient world because of its brutal efficiency. It was primarily a stabbing weapon, worn on the soldier’s right side. The style varied slightly from the Republic to the Empire but the effect for each was the same. The gladius was indeed an extremely deadly weapon.

In the ancient world, shields were of primary importance for defending the bearer against all manner of attacks from arrows and sling stones, to cavalry charges, and a rush of roaring Celts. The Roman legionary’s shield was called a scutum. This was a very large, heavy rectangular or oblong shield with a large boss in the middle that could be used to smash the face of an attacker. It would protect more than half of a soldier standing up, and was used to great effect in military formations such as the tustudo, or tortoise formation.

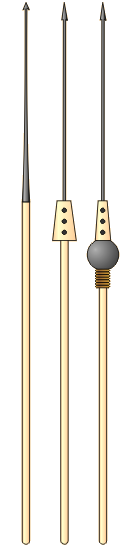

What ancient warrior’s kit would be complete without a spear? The Roman soldier’s spear was called a pilum. This differed from the spears of the ancient Greek hoplite in that it was much lighter and could be used only once. It was however, very effective at piercing armour and flesh because of its fine point. A hail of these was truly deadly and was the Romans’ first offensive weapon after artillery. And, once thrown, it could not be picked up by the enemy and thrown back due to the special design that ensured the tip broke off or bent upon impact making it useless.

For an optio, like Gaius Justus Vitalis in the early part of The Carpathian Interlude, a hastile was carried instead of a pilum. The hastile was a staff carried by that particular rank of officer and though it was symbolic of his rank it could also be used as a weapon if need be.

When the fighting inevitably came to close quarter combat, and pila and gladii were spent or lost, the Roman dagger, called a pugio, was what was called for. This blade, apart from having practical uses such as cutting meat or sharpening a stake, this could be thrust into the side of an enemy when he came too close for comfort. The pugio was worn at the soldier’s left side and secured tightly at the waist for a quick and easy draw.

So there you have it! These are the main weapons of a Roman legionary which they would carry on the march and into battle. They would never leave his side whether he was sleeping or digging ditches and ramparts at the end of the day.

The question you have to ask yourself is whether these weapons, honed and perfected over centuries of use, would be enough to defeat an enemy that feels neither pain nor fear, an enemy that will keep coming at you until you do one thing…

In Part III of The World of The Carpathian Interlude, we’ll be looking at the armour and clothing of a Roman soldier.

Thank you for reading.

The General Muleteer: Publius Ventidius Bassus

Those of you who have read the books in the Eagles and Dragons series will know that they are set during the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus who waged a mostly successful war on Rome’s longstanding enemy, the Parthian Empire.

What you may not know, however, is that long before Severus, Verus, Trajan, and Mark Antony’s campaigns, there was a Roman who was the original punisher of the Parthians.

His name was Publius Ventidius Bassus.

Denarius of Publius Ventidius Basso – minted during Triumvirate of Mark Antony, showing Jupiter on right holding a scepter and olive branch (Wikimedia Commons)

We all hear about the big names of history often enough, but once in a while, I like to highlight some of the secondary and tertiary characters who played a role in the history of the ancient world.

If you missed the previous post on Gaius Asinius Pollio, the founder of the first public library in ancient Rome, you can read that one by CLICKING HERE.

But today, we’re going to take a very brief look at Ventidius.

When I came across Ventidius I couldn’t help but admire his rise from very humble beginnings to the heights of glory on the battlefield for Rome.

He was not from Rome, but rather from Picenum, the birthplace of Pompey the Great, and located in what is now Abruzzo, to the East of Rome.

When the Social War of 91-88 B.C. broke out – this was the war between Rome and the Italian allies – the young Ventidius was in the eye of the storm.

After the Samnite Wars, Rome basically controlled the Italian allies, and the terms that were reached eventually led to great inequalities around money, land ownership, foreign policy, troop levies and more.

This left the Italian allies in poverty, despite their having contributed so many men to Rome’s legions.

In 91 B.C. the Tribune of the Plebs, Marcus Livius Drusus, proposed a series of fair reforms to remedy the situation with Rome’s allies, but for this he was assassinated.

When the Italian allies heard this, they declared independence and war broke out. Most of the Latin cities remained loyal to Rome, but a confederation of eight tribes joined forces (with their Roman-trained men) with the capital at Corfinium, in Abruzzo.

Ventidius and his mother were taken prisoner in the ensuing slaughter of that war and paraded through the streets of Rome in the subsequent triumph of the Roman general, Pompeius Strabo.

But Ventidius survived his ordeal, and as he grew up he became a skilled muleteer. Eventually, he joined the Roman army and after some time, came to the notice of Julius Caesar.

During Caesar’s Civil War, Ventidius acquitted himself admirably and came to be one of Caesar’s favourites.

After the assassination of Julius Caesar, Ventidius threw in his lot with Mark Antony who, after the creation of the Second Triumvirate, sent Ventidius to hold the Parthians back.

When the Parthians invaded Cilicia in 40 B.C., along with some Roman mercenaries led by Quintus Labienus, Ventidius went to meet them head-on with several legions of his own.

The muleteer from Picenum now had a large command!

Ventidius crushed the Parthian forces in two major battles: the Battle of the Cilician Gates, and a battle at the Amanus Pass.

Antony heard the news in Athens and celebrated:

It was while he was spending the winter at Athens that word was brought to him of the first successes of Ventidius, who had conquered the Parthians in battle and slain Labienus, as well as Pharnapates, the most capable general of King Orodes. To celebrate this victory Antony feasted the Greeks, and acted as gymnasiarch for the Athenians. He left at home the insignia of his command, and went forth carrying the wands of a gymnasiarch, in a Greek robe and white shoes, and he would take the young combatants by the neck and part them. (Plutarch, The Life of Antony)

The Parthians were not to be deterred however. They proceeded to bring a massive force into Syria, this time led by Pacorus, the son of King Orodes.

Ventidius’ legions marched to meet the Parthians and utterly crushed them and slew Prince Pacorus at the battle of Cyrrhestica.

Because of Ventidius’ victory, the Parthians were held back in Media and Mesopotamia, and Rome attained a sort of vengeance for the horrible defeat of Marcus Licinius Crassus and his legions years before at the battle of Carrhae.

After the battle of Cyrrhestica, Ventidius pursued the Roman allies who had sided with the Parthians – mainly Antiochus of Commagene – and laid siege to them at a place called Samosata.

When Antiochus proposed to pay a thousand talents and obey the behests of Antony, Ventidius ordered him to send his proposal to Antony, who had now advanced into the neighbourhood, and would not permit Ventidius to make peace with Antiochus. He insisted that this one exploit at least should bear his own name, and that not all the successes should be due to Ventidius. But the siege was protracted, and the besieged, since they despaired of coming to terms, betook themselves to a vigorous defence. Antony could therefore accomplish nothing, and feeling ashamed and repentant, was glad to make peace with Antiochus on his payment of three hundred talents. After settling some trivial matters in Syria, he returned to Athens, and sent Ventidius home, with becoming honours, to enjoy his triumph. (Plutarch, The Life of Antony)

When I read this passage from Plutarch, I can’t help but shake my head at Antony’s jealousy of Ventidius.

It would obviously not do for Antony, who had always lived in the shadow of Julius Caesar, who was Triumvir of the East, to be outdone by a mere muleteer from Picenum.

But he was.

Publius Ventidius Bassus, a man who had worked his way up the ranks of the Roman army, had done what no Roman had done before, nor would do again for a long time.

He was the only Roman general (not an emperor) to celebrate a triumph for victory over the Parthians.

A Triumphal Procession – Ventidius would have celebrated in similar fashion back in Rome. The only general to be awarded a triumph for victory over the Parthians

And the sad thing is that we never hear of Ventidius again in history.

Ventidius… was a man of lowly birth, but his friendship with Antony bore fruit for him in opportunities to perform great deeds. Of these opportunities he made the best use, and so confirmed what was generally said of Antony and Caesar, namely, that they were more successful in campaigns conducted by others than by themselves. (Plutarch, The Life of Antony)

I’ve been told by some folks that people only like to read stories about the ‘marquee characters’ of history, people like Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, or Alexander the Great.

But I have to disagree with this. When I read about men like Ventidius, I’m captivated by their story, and because there are so few details about their lives compared with the big names of history, I find myself filling in the blanks, trying to figure out how they did what they did, how they might have felt when they achieved the heights of glory.

Now that makes a great story! Not only do I want to read about these secondary and tertiary characters, I also want to write about them, to tell their story as more than an anecdote of history whispered in the shade of a larger tree.

Thank you for reading.

Oh, Picts!

We’re heading into the wilds of Caledonia in this week’s post.

I wanted to discuss a topic that is often neglected although it is very interesting: the Picts and Pictish art.

As I’ve been packing for a move, I discovered some of my old photos from my days in St. Andrews, Scotland. I came across a packet of prints from an outing with some of my MLitt colleagues to visit Pictish sites in Angus and Perthshire.

The main attraction for us was the wide array of ornate carvings on several Pictish gravestones, most of which are maintained by Historic Environment Scotland at the Meigle Museum which is itself an old school house on the A94 Coupar Angus to Forfar road (for those of you who are interested in visiting). This little museum is a true gem and well worth a visit.

Before looking at the carvings however, I suppose I should answer one simple (or not so simple) question. Who were the Picts?

In brief, they are the direct descendants of the Caledonii, the blanket name given to those tribes who lived in the lands north of the Firth of Forth.

We hear about the latter in relation to the Roman invasion of what is now Scotland by Agricola in AD 79. The action-packed movie Centurion, with Michael Fassbender, which came out in 2010, deals with Agricola’s operations north of the Firth of Forth and the presumed disappearance of the Ninth Legion. In the film, the Caledonii/Picti are portrayed as a society run by a warrior elite, the members of which paint themselves with blue woad. The film is very entertaining, if not violent, but the best thing is that it was filmed where much of the history presumably took place. It’s worth a gander for that, if anything.

But were the Picts simply a mass of blue barbarians as they’re so often portrayed? Likely not.

Contrary to the usual portrayal, the Picts were not simply one enormous group living and fighting north of the Antonine Wall. They were indigenous Celts and the term ‘Picti’, like ‘Caledonii’ or ‘Maeatae’ is more of a blanket term that included approximately twelve Celtic tribes north of the Forth and Clyde rivers. These were recorded by the Roman geographer Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. Because of the military threat posed by Imperial Rome, the Celts in the area amalgamated into two larger groups. The Caledonii and the Maeatae and, in turn, came to be later referred to as ‘Picti’.

The tribal federation survived the various Roman incursions (the last one being the Severan invasion of Scotland in the early 3rd century – the setting for Warriors of Epona). As a result the Picts were able to develop mechanisms of kingship and by the 6th century there was a Pictish kingdom.

In Pictish art, there are certain recurrent symbols such as those found on the Aberlemno stone including the ‘serpent’, the ‘double-disc’, the ‘crescent’ and the ‘Z-rod’. When I visited the Meigle museum I was struck immediately by the amount of Christian imagery, having had in my mind typical images of paganism when it came to the Picts. The presence of crosses and other Christian images is due to the conversion of the Picts to Christianity after the Irish abbot of Iona, St. Columba, ventured into ‘Pictland’ in AD 565. Columba met the Pictish king, Bridei son of Maelchon in a fortress near the River Ness and thus began the conversion of the Picts, a process that was complete by about AD 700.

The Pictish symbol stones are one of the most important sources for information about the Picts, and the symbols, common from one end of Scotland to the other, were widely understood by all the tribes. Now, however, we know very little of their actual meaning except that they functioned as memorial stones or territorial boundary markers.

The church yard at Meigle contained a large number of Pictish stones, implying that Meigle was itself a very important centre of burial for the Pictish church and under the patronage of the kings of the Picts. Eventually however, Pictish rule, which had survived the onslaught of Rome in Late Antiquity, was taken over by the Gaelic-speaking settlers of Dalriadia (or ‘Dal Riata’ – modern Argyll) which led to the reign of the Scots King, Kenneth mac Alpin and his subsequent dynasty.

Before we bid farewell to the Picts however, there is an interesting Arthurian connection with Meigle and one of the Pictish stones (cross-slab no.1).

On entering the graveyard at Meigle, there is a grassy mound known as Vanora’s Grave. Local tradition has it that Vanora was actually Queen Guinevere, the wife of Arthur. Vanora was abducted by the Pictish king, Mordred, and held captive near Meigle. When she was returned to her husband after this forced infidelity, she was sentenced to death by being torn apart by wild beasts, hence the scene of Vanora’s death on the back of cross-slab no.1. Her remains were buried at Meigle.

Tradition also says that Vanora (and Guinevere for that matter) was barren and it is believed that any young woman who walks over her grave risks becoming barren herself. True or not, this is yet another interesting anecdote of history and legend.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post. Once more, if you ever get the chance to visit Meigle’s museum and some of the stones in the surrounding area, it’s well worth it.

If Picts are your thing, then you may also wish to take a look at the map and pamphlet of Pictish sites released by the Angus Council by CLICKING HERE.

Thank you for reading!

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part V – Legions in the North: The Romans in Scotland

Warriors of Epona is set against the backdrop of the Severan invasion of Caledonia (modern Scotland). It was a massive campaign, and Rome’s last major attempt at subduing the tribes north of the Antonine Wall.

However, this was not the first time Rome had attempted to invade Caledonia. In fact, Septimius Severus’ legions were using the infrastructure of previous campaigns into this wild, northern frontier.

In this fifth and final part of The World of Warriors of Epona, we’re going to look briefly at the Roman actions in Caledonia prior to and including the campaigns of Emperor Septimius Severus.

The full scale conquest of Britannia was undertaken in A.D. 43 under Emperor Claudius, with General Aulus Plautius leading the legions. Campaigns against the British tribes continued under Claudius’ successor, Nero in A.D. 68.

The conquest of the South of Britain involved overcoming the tribes, including Boudicca and the Iceni, the Catuvellauni, the Durotriges, the Brigantes, and others, and the attempted extermination of the Druids on the Isle of Anglesey.

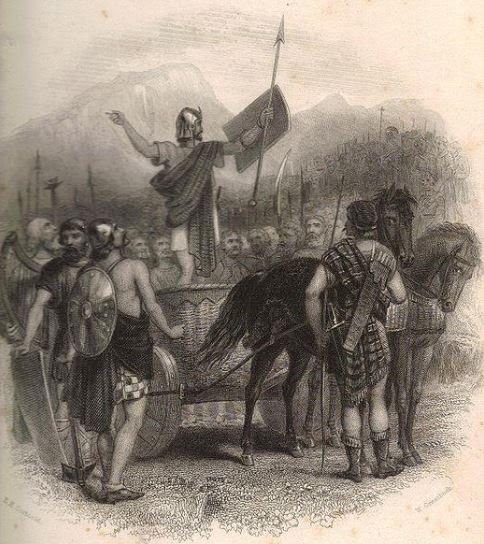

Boudicca

Eventually, after much blood and slaughter, the South was subdued, and the Pax Romana began to take root in that part of Britannia. (It pains me to gloss over so large a part of the history of Roman Britain, but we’re talking about Caledonia here…)

It was not until A.D. 71 that Rome decided it was time to invade Caledonia, and the man assigned this task was Quintus Petillius Cerialis, a veteran of the Boudiccan Revolt, and governor of Britannia at that time.

Once Cerialis’ legions were able to break through the Brigantes, it was time to press north into Caledonia.

The person who is most associated with these initial campaigns in Caledonia is none other than Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who had served in the campaigns against Boudicca in the South and who was also governor of Britannia from A.D. 77-85.

Agricola – Statue at Roman Baths, Bath, England

In around A.D. 80, Emperor Titus (A.D.79-81) ordered Governor Agricola to begin the campaigns into Caledonia by consolidating all of the lands south of the Forth-Clyde (roughly between Edinburgh and Glasgow). This involved taking on the tribes of the Borders, including the Selgovae, Maeatae, Novantae, and Damnonii.

It is in during this campaign that the fort at Trimontium, and many others were established in the Borders.

Commemorative stone at Newstead, in the Scottish Borders

By A.D. 81, Emperor Domitian had decided to order Agricola and his legions into Caledonia, and within two years, Agricola is said to have brought the Caledonians to their knees at the Battle of Mons Graupius.

He [Agricola] sent his fleet ahead to plunder at various points and thus spread uncertainty and terror, and, with an army marching light, which he had reinforced with the bravest of the Britons and those whose loyalty had been proved during a long peace, reached the Graupian Mountain, which he found occupied by the enemy. The Britons were, in fact, undaunted by the loss of the previous battle, and welcomed the choice between revenge and enslavement. They had realized at last that common action was needed to meet the common danger, and had sent round embassies and drawn up treaties to rally the full force of all their states. (Tacitus, Agricola; XXIX)

The Roman historian, Tacitus, was actually Agricola’s son-in-law, and his account, De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae, provides us with the best first-hand account of Agricola and his invasion of Caledonia.

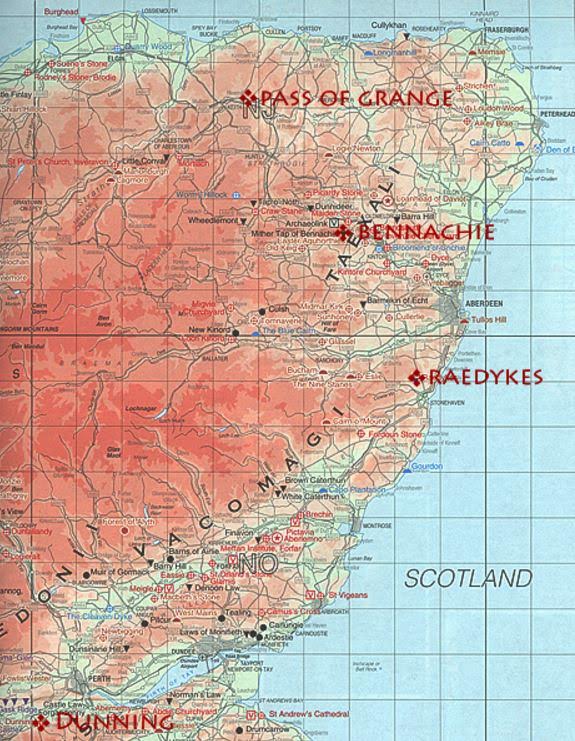

Possible locations for Battle of Mons Graupius

This is a time of legions exploring the unknown reaches of the Empire.

Sadly, the battlefield for Mons Graupius has not been identified, though there are certain candidates.

What is fortunate, however, is that Agricola’s legions left a long train of breadcrumbs in the form of marching camps, legionary bases, watch towers and of course, roads, all the way to northern Scotland.

And it is network of war that was to be used in later invasions of Caledonia.

Early Roman campaigns in Caledonia

War broke out again on the Danube frontier at this time, and so Roman man-power was sucked out of Britannia and Caledonia to meet threats elsewhere in the Empire.

And so, the legions in Caledonia went into a period of retrenchment and pulled back to the Forth-Clyde by A.D. 87.

By the time of Emperor Trajan’s reign, c. A.D. 99, Rome had retreated farther to the South to the Tyne-Solway, the future line of Hadrian’s Wall, construction of which began in A.D. 122.

The Caledonian lands for which Agricola and his legions had fought, had been given up for the time being.

Hadrian’s Wall

As was the case for centuries to come, the lands between the Forth-Clyde line, and the Tyne-Solway line, the area known today as the Scottish Borders, went into a period of push and pull, of occupation, retreat, and re-occupation.

It was during the reign of Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161) that it was deemed necessary to re-occupy the lands lost during the Flavian period, and so the army advanced again across the borders, using those same roads and forts that had been constructed by Agricola, and constructing new ones.

Twenty years after construction began on Hadrian’s Wall, Antoninus Pius ordered the construction of a new wall in Caledonia itelf in A.D. 142. This was the Antonine Wall, and it’s earth and timber ramparts ran the width of Caledonia from the Forth to the Clyde in an attempt to hem the raucous tribes in on their highlands.

The Antonine Wall

But, after more campaigning and entrenchment by Rome, the Antonine Wall was abandoned during the reign of Marcus Aurelius in around A.D. 163.

A few outposts remained in use to the north of Hadrian’s Wall, but for the most part, the bones of the Empire were left to rot and be overwhelmed by the Caledonians and their allies.

For the next forty years, the northern tribes became a menace, breaking through the frontier defences twice, once during the reign of Commodus (c. A.D. 184) and then again during the early part of Septimius Severus’ reign in A.D. 197.

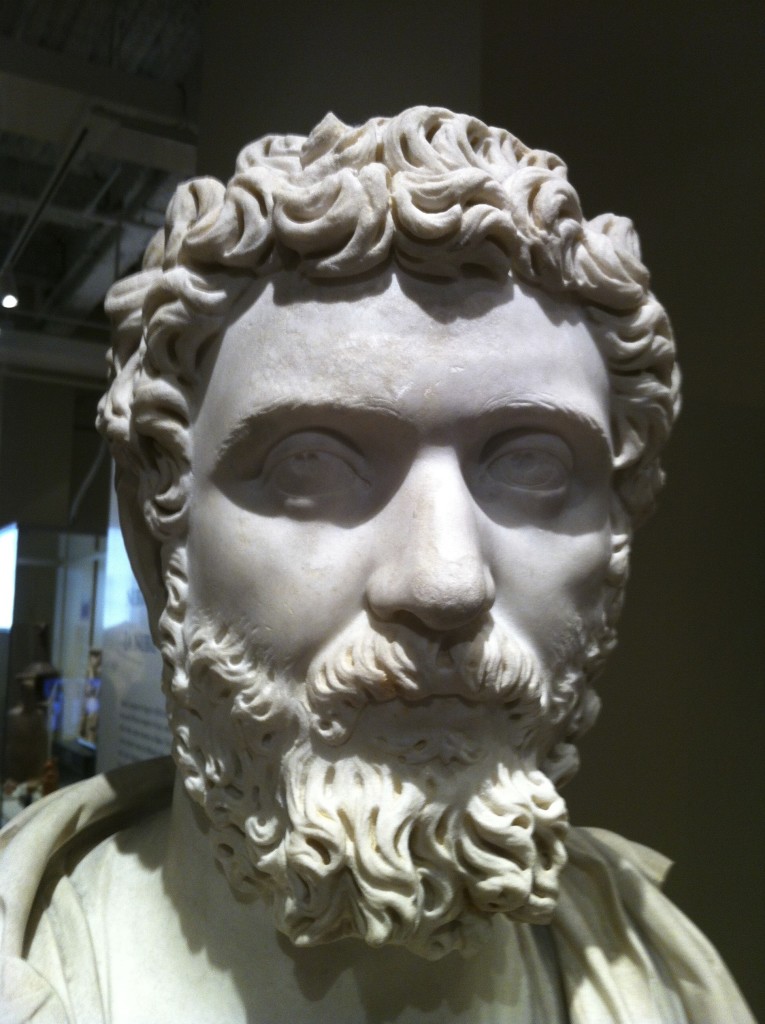

Septimius Severus

When Septimius Severus took the imperial throne, he was immediately engaged in consolidating the Empire after the civil war, and then taking on the Parthian Empire. He was a military emperor, and he knew how to keep his troops busy, and how to reward them.

The Caledonians had been a thorn in Rome’s side for a long while at that time, but it was not until A.D. 208 that Severus was finally able to deal with them. And so, the imperial army moved to northern Britannia, poised to take on the Caledonians once again.

We’ve already touched on Severus’ campaign in previous parts of this blog series. However, it’s important to note that this is believed to be the last real attempt by Rome to take a full army into the heart of barbarian territory.

Severus moved on the Caledonians with the greatest land force in the history of Roman Britain, making use of his predecessors’ fortifications (such as the Gask Ridge frontier) and roads, and penetrating almost as far as Agricola’s legions over a hundred years before.

According to Cassius Dio, when the inhabitants of the island revolted a second time, Severus:

…summoned the soldiers and ordered them to invade the rebels’ country, killing everybody they met; and he quoted these words: ‘Let no one escape sheer destruction, No one our hands, not even the babe in the womb of the mother, If it be male; let it nevertheless not escape sheer destruction.

Rome was poised for a final push, and ultimate victory over the Caledonians.

Goddess Fortuna

But Fortuna was not on Severus’ side, for it was at that time that his chronic health problems finally got the better of him.

In A.D. 211, the man who had won a brutal civil war, and who had finally brought the Parthians to heel, died at Eburacum (modern York) in Britannia.

Roman Tower at Eburacum (York)

His son, Caracalla, who was ill-equipped to handle the situation, struck a deal with the Caledonians, abandoning all the headway his father had made in that northern land, and all of the blood shed by fifty-thousand Romans in the Severan campaign.

What happened after the death of Severus is for another story (i.e. for the next book!). However the Severan conquests in Caledonia did usher in a fleeting period of tranquility.

Later expeditions into the North were mounted in c. A.D. 296 by Constantius Chlorus, and by his son, the future Emperor Constantine, in A.D. 306. However, neither of these campaigns were on a scale comparable to the Severan campaign.

Like other remote corners of the Empire, Caledonia must have seemed like a lost cause.

Roman Cavalry

But the Eagles and Dragons series is not yet finished with this exciting period of history in Roman Britain. Like Severus, we are poised for a final punitive push into the Highlands.

It’s a fascinating period in Roman history, and I hope you have enjoyed this journey through The World of Warriors of Epona with me. If you missed any of the previous blog posts in this series, you can read them all on one page by CLICKING HERE.

If you would like to learn a bit more about the Romans in Scotland, I highly recommend checking out the documentary Scotland: Rome’s Final Frontier with Dr. Fraser Hunter.

Warriors of Epona is out now on Amazon, Apple iBooks/iTunes, and Kobo, so be sure to get your copy today.

Remember, if you haven’t yet read any of the Eagles and Dragons novels, and if you want to get stuck in, you can start with the #1 Best Selling prequel novel, A Dragon among the Eagles. It’s a FREE DOWNLOAD on Amazon, Apple iTunes/iBooks, and Kobo.

Thank you for reading!

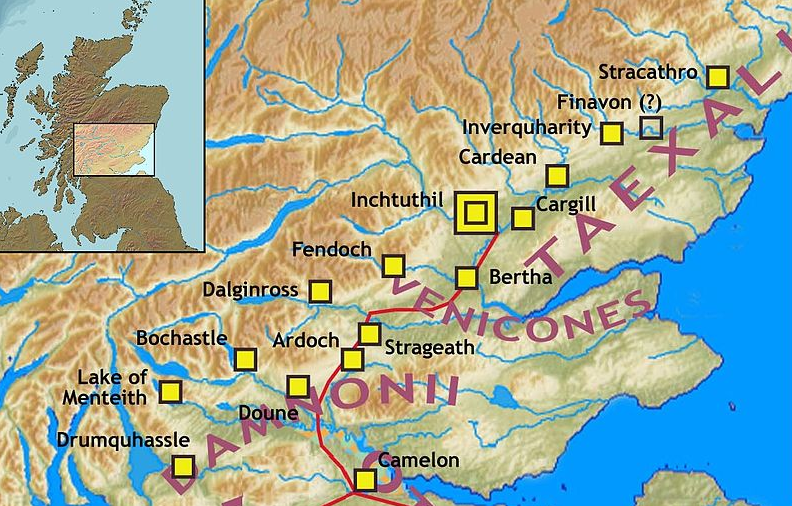

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part IV – Battle Line: The Gask Ridge Frontier

When most think of the Romans in Britannia or Caledonia, almost always the first thing that comes to mind is Hadrian’s Wall.

But there is another frontier that many people may not know of. You may have heard of some of the forts or camps that make up a part of this frontier, such as the legionary base at Inchtuthil.

Roman re-enactor watching the frontier

I’m talking about a line of forts and camps known as the ‘Gask Ridge’.

Research on this particular frontier has been less in depth than either the Antonine or Hadrianic walls. However, over the past ten years or so, the Gask Ridge has received its due attention thanks to the efforts of Birgitta Hoffmann and David Woolliscroft who have spearheaded the Roman Gask Project.

The importance of this frontier cannot be over-emphasized.

Gask Ridge Forts (Wikimedia Commons)

The Gask Ridge frontier has seen action in every one of Rome’s Caledonian campaigns and some of the research even shows that it was the first chain of forts in northern Britain, predating the other walls.

Some believe it is the first such frontier in the Empire!

It consists of a long line of forts, watchtowers, and temporary marching camps that run from the area of Stirling, on the Antonine Wall, past Doune, along the edge of Fife and up into Angus, all the way to Stracathro.

This is a very impressive line of defence built by Rome with the intent of holding the Caledonii at bay, and separating the highlands from the flatter plains leading to the North Sea.

Artist Impression of Caledonian Warriors

In writing Warriors of Epona, the trick was finding out which forts may have been in use during the campaigns of Septimius Severus in the early 3rd century A.D.

The forts of the Gask Ridge were used mostly during Agricola’s campaign in the late first century, and then by Antoninus in the mid-second century.

Roman road along Gask Ridge in Perth and Kinross

The Romans definitely knew how to pick a strategic location along the perfect line of march, so it’s likely marching camps would have been reused in later campaigns. But some of that is supposition.

One site that we know was built as part of the Severan campaign was the legionary fort at Carpow, on the banks of the Tay. With a large part of a legion stationed there, the supply chain could be maintained by sea with Roman galleys coming up the Tay. It was also at this time that some believe the first Tay Bridge was built when Severus ordered the creation of a boat or pontoon bridge to the Angus side of the river.

Aerial view of Horea Classis site (Carpow)

Carpow was a large base of operations intended to make a statement – Rome was going to stay this time! Severus was a military emperor who liked to prove his point. He was in Caledonia to finish what other Roman emperors had started, just as he did in Parthia.

The Gask Ridge plays a key role in Warriors of Epona, especially the forts that may have seen re-use during the third century, among them the forts at Camelon, Ardoch, Fendoch, and Bertha, the latter being where Lucius Metellus Anguis establishes his forward base.

Ardoch Roman camp remains

Of course, one of the exciting things about writing historical fiction, after the research, is filling in the gaps and exploring possibilities.

Because research on the Gask Ridge is relatively new, we can certainly look forward to learning more from Hoffmann, Woolliscroft, and everyone else on the Roman Gask Project team who are leading the charge to further our knowledge of this ancient frontier.

One thing that I have discovered over the years is that even though the history and research are very important, at the end of the day, in fiction, the story must come first.

With Warriors of Epona, history and story have come together nicely, and that has been pure magic!

Cheers, and stay tuned for the fifth and final part of The World of Warriors of Epona.

Aerial view of Fendoch and the Sma’ Glen from the south with the fort on the low plateau in the right foreground.

If you are interested in reading more about the Roman Gask Frontier, or about the Romans in Scotland, do have a look at the following resources:

The Roman Gask Project: http://www.theromangaskproject.org/

Rome’s First Frontier: The Flavian Occupation of Northern Scotland. By D. J. Woolliscroft and B. Hoffman. Pp. 254. ISBN: 0 7524 3044 0. Stroud: Tempus. 2006.

Warriors of Epona – Eagles and Dragons Book III is one sale now!

But remember! If you have not yet read any of the Eagles and Dragons novels, and if you want to start off on an adventure in the Roman Empire, you can pick up the #1 Best Selling prequel novel, A Dragon among the Eagles. It is a FREE DOWNLOAD on Amazon, Apple iTunes/iBooks, and Kobo.

The World of A Dragon among the Eagles – Part V – The City of Alexander

In this fifth and final part of The World of A Dragon among the Eagles, we’re going to take a brief look at a city that has perhaps captured history-lovers’ imaginations more than any other – Alexandria.

There were, of course, many Alexandrias in the world, stretching from Greece to India, but the one we are going to discuss, and which provides the setting for the final third of A Dragon among the Eagles, is Alexandria in Egypt.

Statue of Alexander in downtown Alexandria

Alexandria was founded by Alexander the Great in about 331 B.C., near the westernmost branch of the Nile Delta. From a few scattered fishing villages, it grew to become one of the world’s great metropolises, a centre for trade, religion and learning the world had not really seen to that point.

There are many origin stories to the foundation of Alexandria, but the one I often refer to is that given by Arrian who says the following:

From Memphis he sailed down the river again with his Guards and archers, the Agrianes, and the Royal Cavalry Squadron of the Companions, to Canobus, when he proceeded round Lake Mareotis and finally came ashore at the spot where Alexandria, the city which bears his name, now stands. He was at once struck by the excellence of the site, and convinced that if a city were built upon it, it would prosper. Such was his enthusiasm that he could not wait to begin the work; he himself designed the general layout of the new down, indicating the position of the market square, the number of temples to be built, and what gods they should serve – the gods of Greece and the Egyptian Isis – and the precise limits of its outer defences. He offered sacrifice for a blessing on the work; and the sacrifice proved favourable.

A story is told – and I do not see why one should disbelieve it – that Alexander wished to leave his workmen the plan of the city’s outer defences, but there were no available means of marking out the ground. One of the men, however, had the happy idea of collecting the meal from the soldiers’ packs and sprinkling it on the ground behind the King as he led the way; and it was by this means that Alexander’s design for the outer wall was actually transferred to the ground.

(Arrian; The Campaigns of Alexander, Book III)

There is no real way to know whether this is true or not, but it is not impossible. Alexander was a man of vision, and learned in architecture, planning and much more. As a conqueror of the world, as many saw him, it was to be expected that he create one he hoped would have been a perfect city at the centre of the known world.

The Egyptians had welcomed Alexander as a liberator against the Persians who had disrespected their gods. Alexander, on the other hand, respected Egypt’s ancient gods, and was even declared the son of Zeus Ammon by the famous Oracle at Siwa in the western desert.

Egypt’s new pharaoh had great plans for the city, but he died long before it could be completed. That task fell to Alexander’s friend and general, Ptolemy I, founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty, the last dynasty of Egypt before Rome took over.

Alexandria quickly became a destination that thrived under the Ptolemies, and as the resting place of Alexander the Great’s body, a major tourist destination. It was the greatest of the Hellenistic cities, dwarfing all others.

As time marched on, so did Rome.

Ancient Alexandria in the years after Severus

Alexandria came under Roman jurisdiction in the will of Ptolemy Alexander in 80 B.C. Then, when a domestic dispute broke out between Ptolemy’s children, Ptolemy and Cleopatra, Rome, under Gaius Julius Caesar, stepped in to settle the dispute.

Most of you probably know this part of the story, how Caesar threw his weight behind Cleopatra, making her sole Queen of Egypt in about 47 B.C. They had a son, Caesarion, and the rest is history.

With the death of Caesar, Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra joined forces with the hopes of creating a new, greater Hellenistic world with Alexandria at the centre. But those hopes were dashed by Rome at the Battle of Actium where Octavian came out victorious and as a result, brought Alexandria under the control of Rome.

This is probably one of the most famous periods in Roman history, but it took place two hundred years before A Dragon among the Eagles.

What happened to Alexandria after the Battle of Actium? What did things look like for the city of Alexander?

Even though Rome remained the centre of the Empire, and basically the Mediterranean world, Egypt lost little importance. In fact, it gained, being as it was the granary of the Roman Empire, before the North Africa provinces came to the fore. Alexandria was so important that Octavian kept it under direct imperial control, making it so that Alexandria had no governor, and therefore, no one powerful enough to hold Rome’s grain hostage.

Fertile land of the Nile

Alexandria was beautiful and learned, but it was also tumultuous .

In A.D. 115 it was destroyed during the Greek-Jewish civil war. Luckily, that great phil-Hellene emperor, Hadrian, decided to rebuild the city so that it could continue to thrive.

By the time of A Dragon among the Eagles, when Emperor Septimius Severus and his legions came into Egypt at the conclusion of the Parthian campaign around A.D. 199, Alexandria was once again a metropolis to rival Rome.

Alexandria was always well placed at the crossroads of the world, beside the waters of the Nile Delta, at the edge of the Silk Road, and with free access to the rest of the Mediterranean Sea.

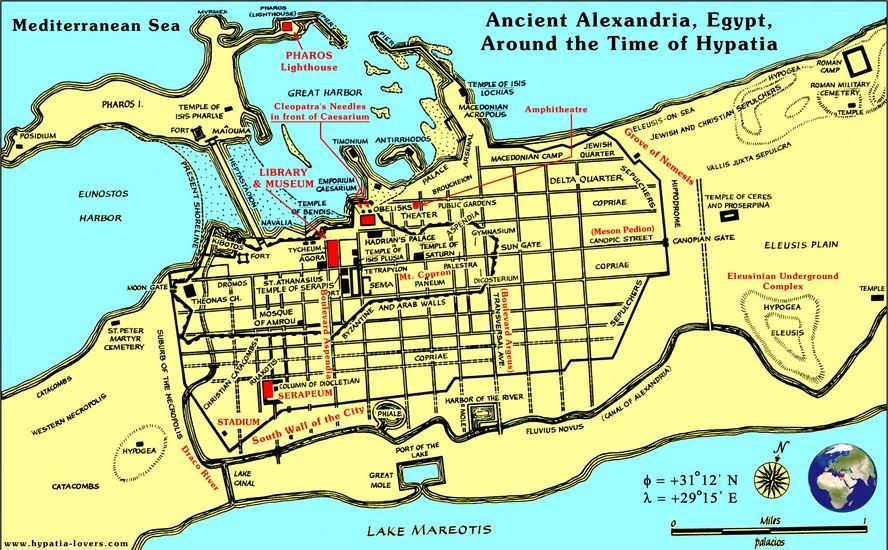

It was built on a narrow strip of land which was sandwiched between the Mediterranean to the north, and the fresh waters of Lake Mareotis to the south.

Alexandrian street scene in movie Agora

To the east of the city was the Eleusis Plain which contained an underground complex where the Eleusinian Mysteries, that major ritual of Ancient Greece, were presumably carried out. Closer to the sea on that side of the city were the Jewish and Christian sepulchers, as well as temples and Roman cemeteries beyond the Grove of Nemesis.

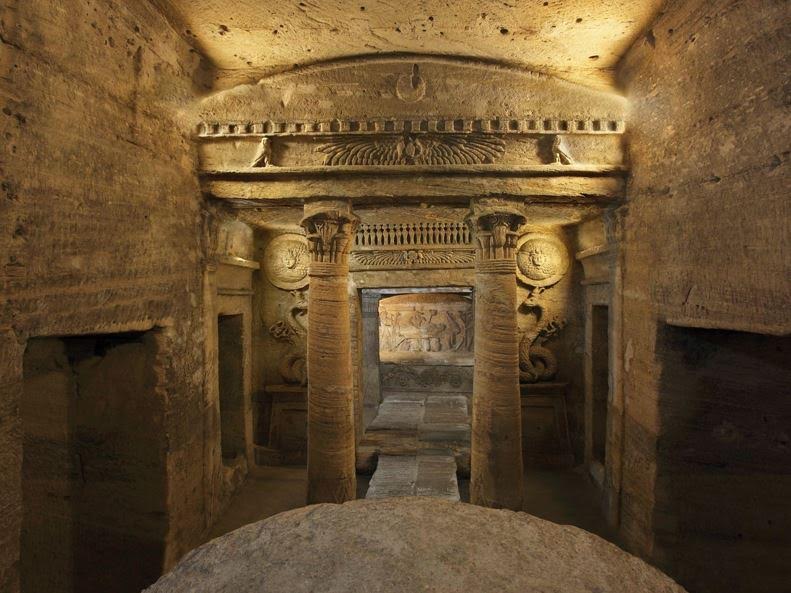

On the western side of the city, beyond the Draco River which ran along the south of the city and into the Fluvius Novus, the Great Canal of Alexandria, was the western necropolis which also contained Christian catacombs.

Alexandrian catacombs with mixture of Egyptian, Hellenistic and Roman styles

If you have seen the movie Agora, with Rachel Weiss, you will have seen a later, dirtier recreation of Alexandria from the time of this particular story.

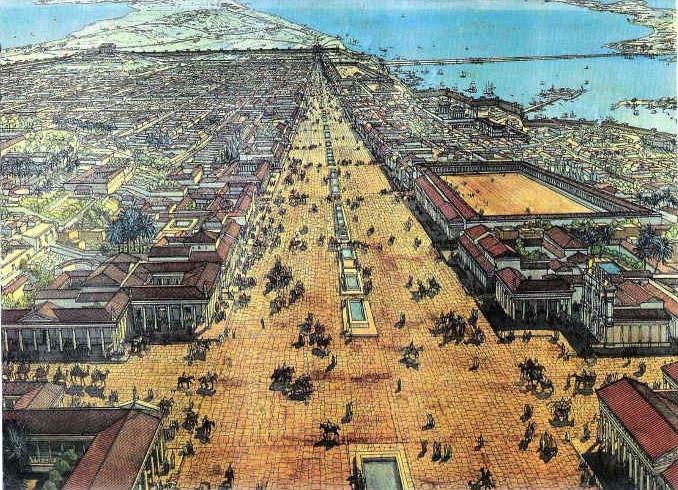

At the heart of Alexandria were the temples and palaces, and the Cema destrict where the tomb of Alexander the Great was located. Through it all ran the great city street known as the Canopic Way.

Alexandria’s Canopic Way (artist impression by Egyptologist Jean-Claude Golvin)

The Canopic Way, with the Sun Gate in the East, and the Moon Gate to the West, was ancient Alexandria’s main artery. It was the place to see and be seen, where giant litters carrying perfumed ladies went back and forth in the shadow of luxurious villas and temples. There were huge fountains running down the middle of the thoroughfare. Perhaps the Canopic Way was a sort of ancient version of Rodeo Drive, or 5th Avenue?

The success and livelihood of Alexandria did not necessarily stem from the richness of the street, nor the number of its temples, but rather from the Great Harbour which was faced by the royal palaces, agora, and the Great Library.

Across the man-made mole known as the Heptastadion, a bridge of about seven stades long, was the island of Pharos, and the structure that beckoned all the world to Alexandria – the Lighthouse.

The City of Alexander today

As one of the wonders of the ancient world, the great lighthouse of Alexandria set this city apart, and if that was the beacon, the library, for many, was what awaited them. It has been said that the previous library, that which stood during the reign of Cleopatra, burned down, and all the treasures it contained with it.

However, there are some theories that say the great library was never fully destroyed, that many of the works survived and that the library continued to send people out into the world to collect copies of every book or work ever created.

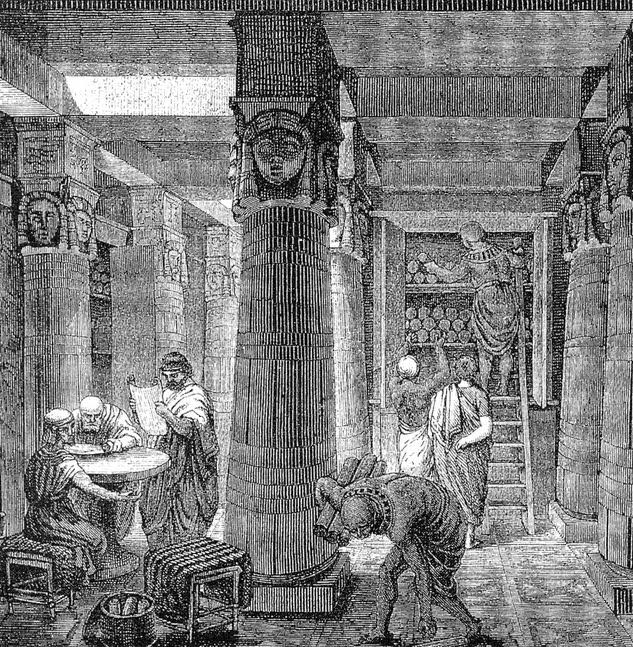

Library of Alexandria

I wonder if Alexandria would have lived up to the Conqueror’s expectations as he was laying out the city with his men’s rations, prior to his defeat of the Persian Empire?

It is ironic that the body of Alexander also became a big draw in Alexandria, for people came from around the ancient world to see this titan among men.

Augustus himself stopped to see Alexander’s body after the Battle of Actium, and successive emperors did likewise, including Septimius Severus who, for some strange reason, closed Alexander’s tomb to the public prior to going on a Nile cruise with his wife, Julia Domna.

Writing about this ancient city was no easy feat. First of all, I had to discover which structures were actually there during this time, and which I could not include.

It was also fun writing about Alexandria, in comparison to Rome, for it was generally believed that Alexandrian morals were much looser than those of Rome, making it something of a brilliant, seedy, learned metropolis.

When Lucius Metellus Anguis arrives in Alexandria, a city he has dreamed of visiting for a long time, he is torn between two worlds.

Can’t really blame the Emperor and Empress for taking a Nile cruise!

This made for some interesting and fun storytelling.

But it seems to me, after the research I’ve done, and after having written in that world, that Alexandria was anything but uniform, despite its logical grid of streets laid out by Alexander.

Alexandria was a world of contrasts, of perhaps the worst and the best that life had to offer. It preserved culture, and destroyed it, but it always rose from the ashes.

Riotous Alexandrians in the movie Agora

The glory days of its early Hellenistic existence were long gone, but perhaps under Rome, it experienced a revival that may not have been possible under the drunken ancestors of Cleopatra? I’m not sure, but if Cleopatra’s father saw the need to have Rome care for it after his death, there must have been a reason for it.

Antony and Cleopatra

Well, that’s the end of this blog series about The World of A Dragon among the Eagles.

I hope you’ve enjoyed it and found it informative, even though I have only but scratched the surface of some of these topics. If you missed any of the posts, or if you would like to re-read them, you can see them all by CLICKING HERE TO READ THE FULL SERIES.

A Dragon among the Eagles, is now available on Amazon and Kobo, and very soon on iTunes/iBooks.

It is also now available in paperback from Amazon and Create Space.

So, if your interest is piqued, download a copy today and let us know what you think by leaving an honest review.

The story continues in Children of Apollo, so be sure to also check that out.

To stay up-to-date with new releases in this and other series by Eagles and Dragons Publishing, be sure to sign-up for the mailing list By Clicking Here. You’ll have first access to new releases, special offers, blog posts, and much more!

Thank you for reading!

The World of A Dragon among the Eagles – Part IV – Cities Under Siege

One of the great things about reading and writing historical fiction is that one is given the chance to journey to a time and place far away from the modern world.

In this fourth part of The World of A Dragon among the Eagles, we’re going on location to some of the places where the action takes place, some of which, sadly, are still making headlines today.

This won’t be an in-depth look at these ancient cities, for their histories are long and varied, and they each deserve their own a book. Here, we’re just going to take a brief look at their place in this story.

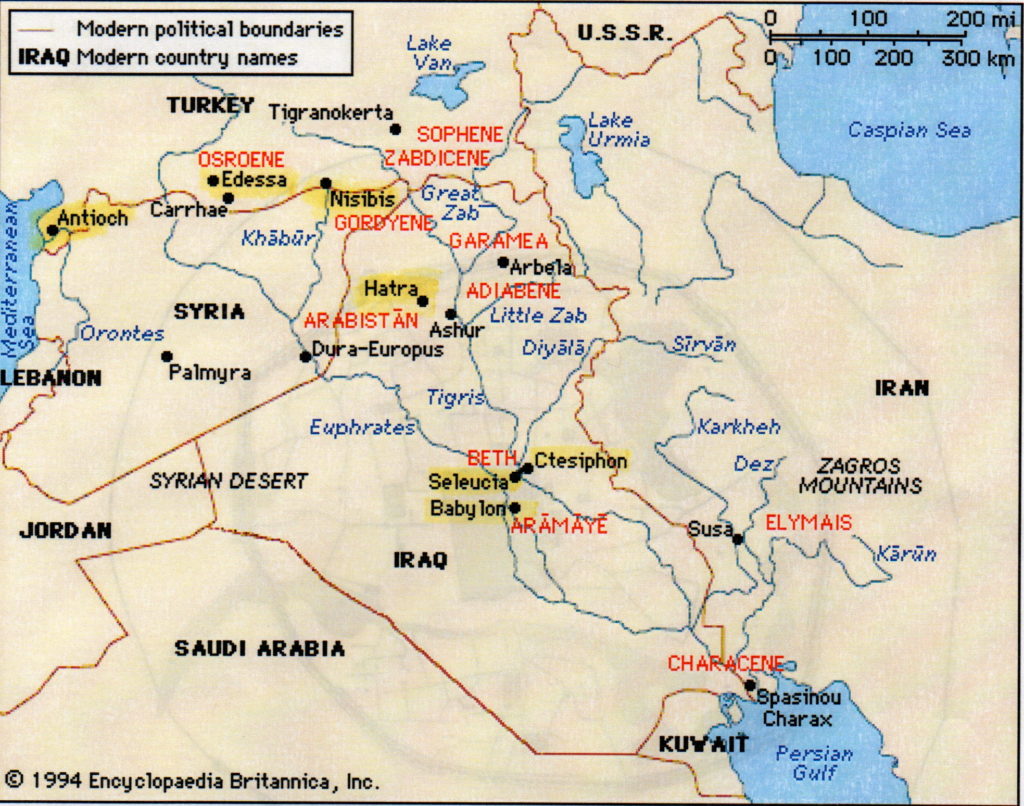

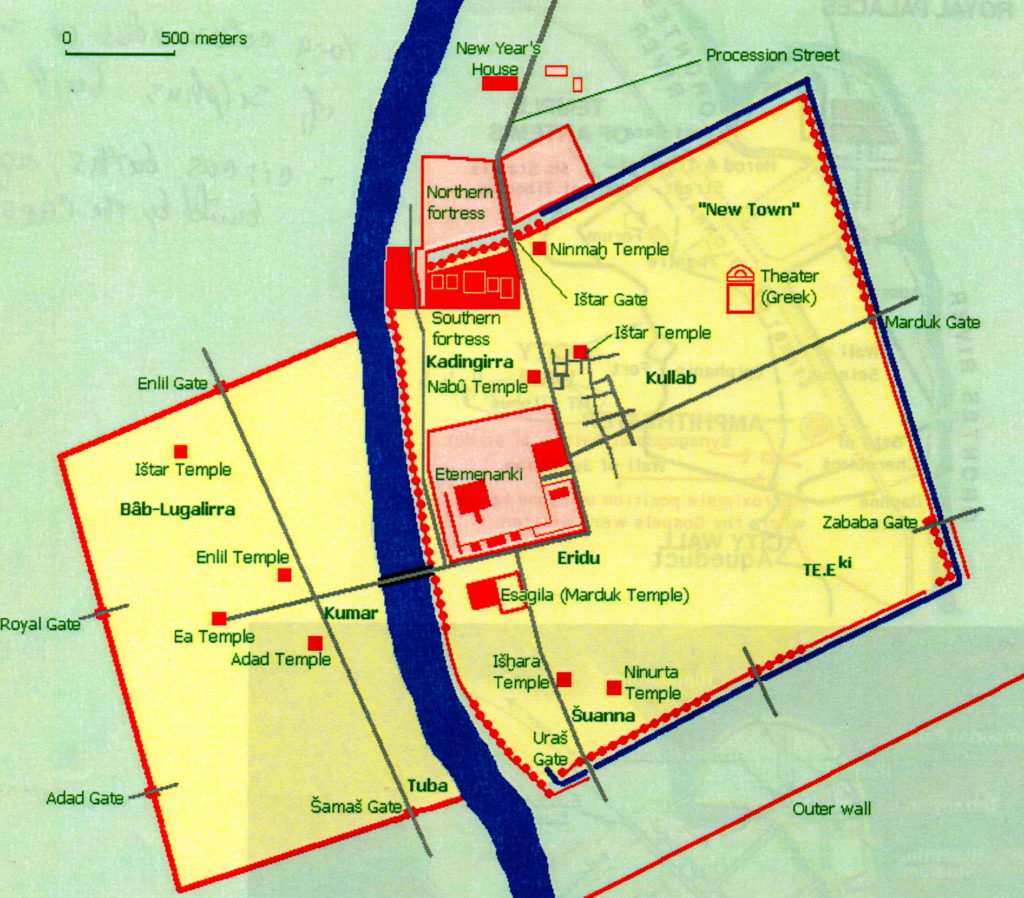

Sites where A Dragon among the Eagles takes place

The first third of A Dragon among the Eagles takes place in Rome, then Athens, and a little at Amphipolis which has gained recent fame for the massive tomb and the excavations there which have been linked to the period of Alexander the Great.

However, we are not going to look at Rome and Athens, as we visit those cities much more in Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra, the sequels to A Dragon among the Eagles. If you would like to read more about Amphipolis, you can read this BLOG POST HERE.

For this blog, we are mainly concerned with the cities where Lucius Metellus Anguis, our protagonist, gets his first taste of war with the Legions.

Mesopotamia is said to be the cradle of civilization, a land of alternating fertility and desert where the first cities were built, and empires made. It also was, and is, a land of war, a land of terrible beauty.

Trooper in modern Iraq

For millennia, successive civilizations have fought over this rich land, a land from which Alexander the Great had decided to rule his massive empire.

In A Dragon among the Eagles, Lucius Metellus Anguis’ legion arrives at the port of Antioch where Emperor Severus has assembled over thirty legions on the plains east of the city.

Antioch, which was then located in Syria, now lies in modern Turkey, near the city of Antyaka. It was founded in the fourth century B.C. by one of Alexander’s successor-generals, Seleucus I Nicator, the founder of the Seleucid Empire.

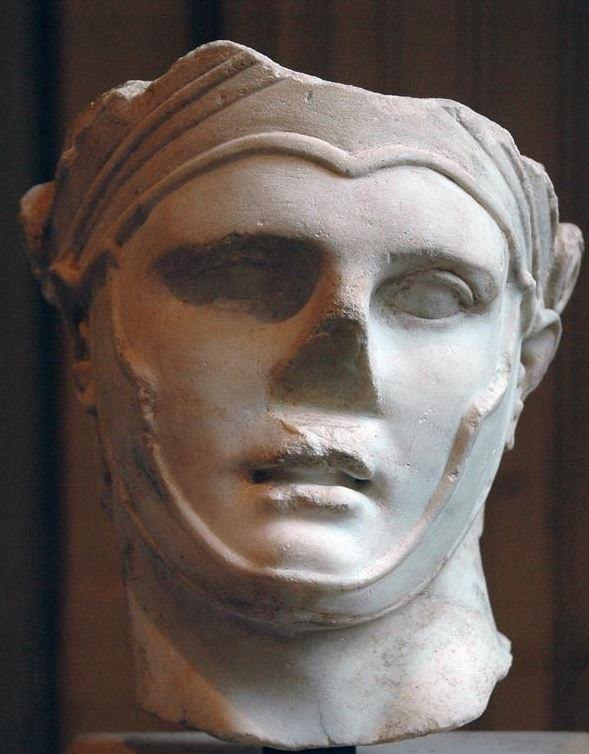

Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus named this city after his son, Antiochus, a name that would be taken by later kings of that dynasty.

Antioch was called the ‘Rome of the East’, and for good reason. It was rich, mostly due to its location along the Silk Road. Indeed, Antioch was a sort of gateway between the Mediterranean and the East, with many goods, especially spices, travelling through it. It is located on the Orontes river, and overlooked by Mt. Silpius.

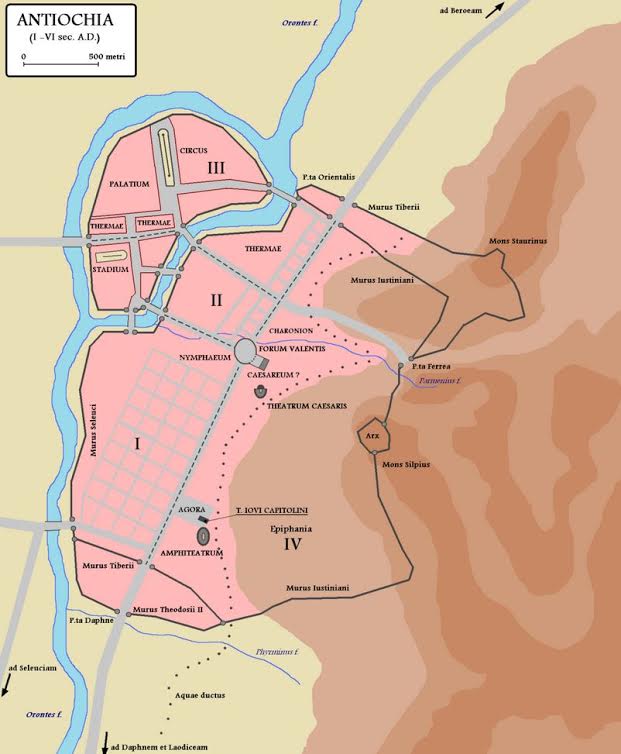

Antioch in the Roman Empire

In the book, we catch a glimpse of this Ancient Greek city that was greatly enhanced by the Romans who saw much value in it. Actually, most of the development in Antioch took place during the period of Roman occupation. Enhancements included aqueducts, numerous baths, stoas, palaces and gardens for visiting emperors, and perhaps most impressive of all, a hippodrome for chariot racing that was 490 meters long and based on the Circus Maximus in Rome.

Antioch, during the late second century A.D., rivalled both Rome and Alexandria. It was a place of luxury and civility that was in stark contrast to the world of war where the legions were headed.

Some ruins of Nisibis today

In writing A Dragon among the Eagles, I have followed the itinerary presented to us by Cassius Dio, the main source for this period in Rome’s history and the Severan dynasty. So, the order in which we are looking at these locales is roughly the order in which Severus’ legions are supposed to have attacked them.

The first real battle in the book, and the first time our main character experiences battle, is at the desert city of Nisibis.

At the time, Nisibis was under Roman control. However, that control was about to break according to Dio, as the Romans inside were just holding onto it. This is due mainly to the leadership of the Roman general, Maecius Laetus, whom we meet in the story.

Laetus managed to hold the defences of Nisibis until Severus’ legions showed up, and was hailed as a hero for it.

Nisibin Bridge – Gertrude Bell’s caravan crossing bridge.

Nisibis was situated along the road from Assyria to Syria, and was always an important centre for trade. This was the only spot where travellers could cross the river Mygdonius, which means ‘fruit river’ in Aramaic. Today it is located on the edge of modern Turkey.

Early in its history, Nisibis was an Aramaen settlement, then part of the Assyrian Empire, before coming under the control of the Babylonians. In 332 B.C. Alexander the Great, and then throughout the Roman-Parthian wars, it was captured and re-captured, over and over.

Such is the fate of strategically placed settlements, especially when they are located along the Silk Road.

Ruins of Edessa

From the bloody fighting in Nisibis, Severus’ forces then moved into the Kingdom of Osrhoene and the upper Mesopotamian city of Edessa, located in modern Turkey.

Edessa was originally an ancient Assyrian city that was later built up by the Seleucids.

Edessa’s independence came to an end in the 160s A.D. when Marcus Aurelius’ co-emperor, Lucius Verus, occupied northern Mesopotamia during one of the Roman-Parthian wars.

From that point on, Osrhoene was forced to remain loyal to Rome, but things changed when the civil war broke out between Severus, Pescennius Niger, and Clodius Albinus. Osrhoene threw their support behind Niger, who was then governor of Syria.

When Severus came out the victor in the civil war, it was inevitable that Edessa and Osrhoene would have to face the drums of war.

Edessa was where King Abgar of Osrhoene, who was sympathetic to the Parthians, was holed up as Severus’ legions advanced.

King Abgar of Osrhoene and Commodus

One has to wonder what King Abgar was thinking as Severus approached this ancient city. Whatever it was, and whatever he said to the Roman Emperor when he arrived, it must have been acceptable, for Abgar was permitted to keep his throne as a client king of the Empire.

There was a siege, but it seems that with King Abgar accepting Rome’s overlordship, and Severus’ need to move south, this is why the Osrhoenes escaped any large scale retribution.

In a way, it was not so for Lucius Metellus Anguis, for whom Edessa proves to be a harsh and enlightening experience.

At this time, Septimius Severus had his sights set on southern Mesopotamia and the great cities of Seleucia, Babylon, and the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon.

Ancient Babylon

The legions made their way south, directly for Seleucia-on-Tigris.

Seleucia, as the name suggests, was built by the Seleucus I Nicator in 305 B.C. as the capital of his empire. It was located sixty kilometers north of Babylon, and just across the Tigris River, on the west bank, from Ctesiphon. Today, Seleucia is located in modern Iraq, thirty kilometers south of Baghdad, and in its day, it was a major city in Mesopotamia.

It was a great Hellenistic city in the third and second centuries B.C., with a rich mixture of Greco-Mesopotamian architecture, and walls enclosing a full 1,400 acres as well as a population of 60,000 people.

When the Parthians took Seleucia, the capital was moved across the river to Ctesiphon and, though the city remained in use and inhabited, it went into a slow decline.

During the Roman-Parthian wars, Seleucia was burned by Trajan, rebuilt by Hadrian, and then destroyed again. Like a battered boxer with heart, it kept rising from the ground until there was no more will to keep it alive.

By the time Severus’ legions were marching on Seleucia, the Parthians had abandoned it completely, giving the Romans a foothold on the Tigris River, opposite their capital.

Seleucia on Tigris c.1927

Ctesiphon would have to wait, however, for there was another magnificent and symbolic prize within Severus’ grasp at that time – Babylon.

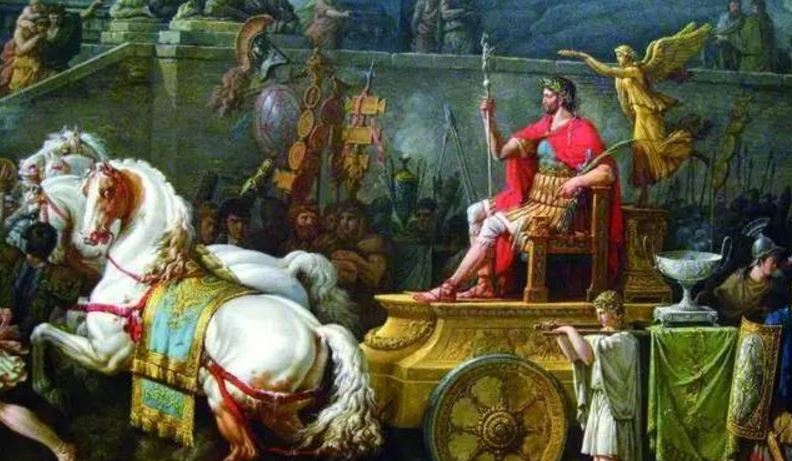

Alexander entering Babylon (Charles Le Brun)

I find that when I utter the name of Babylon, I get chills. Think about it, this is one of the most famous of ancient cities! This was the place that welcomed Alexander the Great with open arms and triumph, the place from which he had decided to rule his titanic empire, and the place where he died.

Babylon was located on the fertile plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Actually, part of it was built over the Euphrates.

The original settlement of Babylon is said to date to about 2300 B.C when it was part of the Semitic Akkadian Empire. It was fought over and rebuilt, and in about 1830 B.C. it became the seat of the first Babylonian dynasty.

From about 1770 B.C. to 1670 B.C. Babylon was the largest city in the world with a population of over 200,000.

Perhaps the most famous period in Babylon’s long and ancient history is during what is known as the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626-539 B.C.), and especially the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 B.C.)

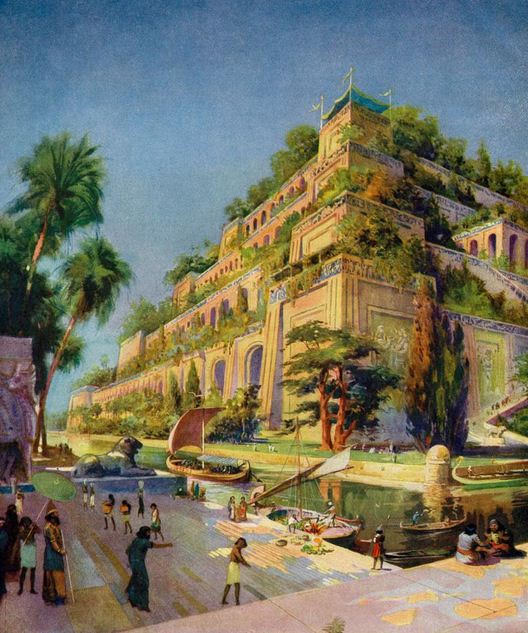

Then Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Nebuchadnezzar was a great builder, and it was he who made Babylon one of the most beautiful cities of the ancient world, home to one of the Seven Wonders.

He built the famed Hanging Gardens of Babylon for his Median wife who missed the lushness of her homeland, and he also constructed the giant ziggurat of Etemenanki beside the temple of Marduk.

Babylon at this time must have been a sort of paradise on earth with the ziggurat as the doorway to the heavens. The walls of the city too, were so big that it was said that two chariots could pass each other as they drove along the top of the walls.

Ishtar Gate of Babylon at Pergamon Museum Berlin

When the Seleucids came onto the scene and Babylon’s power and beauty faded into history, the population was moved to Seleucia, one supposes to bolster the economy of the great new capital envisioned by Seleucus I.

There was a lot of history at Babylon, and it’s not improbable that all the Romans who marched through there thought of Alexander as they approached, including Severus.

But Babylon was a very different place when the legions marched on it late in A.D. 198.

Just as Seleucia had been abandoned, so too was Babylon. And so, with barely a drop of blood being shed, the Romans walked into this ancient city of faded glory in stern silence, their prize almost too easily won.

Ruins of Babylon (Wikimedia Commons)

It was time for the real battle.

With Seleucia and Babylon basically given over to Rome and Severus’ legions, the forces of Rome and Parthia converged on the capital of Ctesiphon.

This time, the Parthians were waiting.

Ctesiphon, compared to the other cities we have seen, was a relatively new settlement on the east bank of the Tigris River, facing Seleucia. It was built around 120 B.C. on the site of a military camp built by Mithridtes I of Parthia. At one point in time, it merged with Seleucia to form a major metropolis straddling the river.

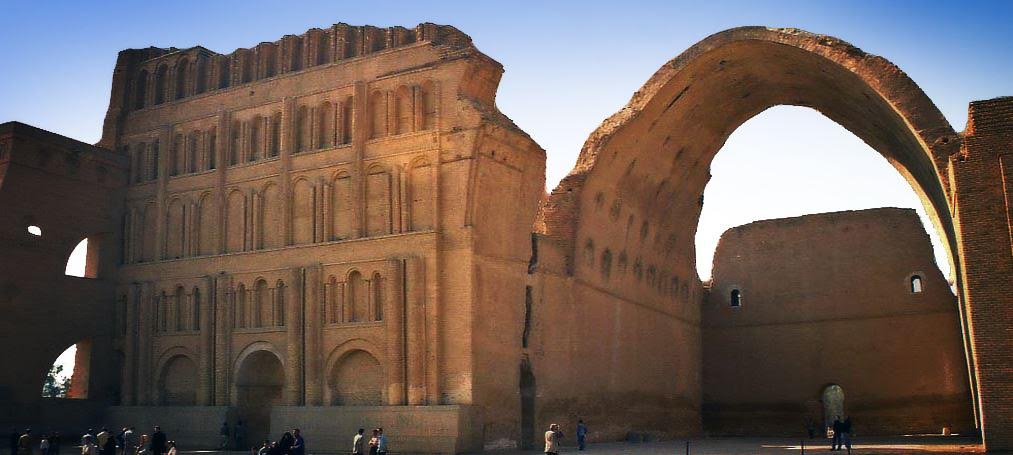

Ctesiphon’s ruins today, including the great audience hall.

During the Roman-Parthian wars, Ctesiphon did not have an easy time of it. It was captured by Rome five times in its history, the last time by Septimius Severus who burned it to the ground and enslaved much of the population.

The Greek geographer, Strabo, describes the foundation of Ctesiphon here:

In ancient times Babylon was the metropolis of Assyria; but now Seleucia is the metropolis, I mean the Seleucia on the Tigris, as it is called. Nearby is situated a village called Ctesiphon, a large village. This village the kings of the Parthians were wont to make their winter residence, thus sparing the Seleucians, in order that the Seleucians might not be oppressed by having the Scythian folk or soldiery quartered amongst them. Because of the Parthian power, therefore, Ctesiphon is a city rather than a village; its size is such that it lodges a great number of people, and it has been equipped with buildings by the Parthians themselves; and it has been provided by the Parthians with wares for sale and with the arts that are pleasing to the Parthians; for the Parthian kings are accustomed to spend the winter there because of the salubrity of the air, but they summer at Ecbatana and in Hyrcania because of the prevalence of their ancient renown.

Being built by the Parthians, Ctesiphon, unlike Seleucia, Babylon, or the other places we have discussed, was a Parthian invention. Probably the greatest structure of this capital was the great, vaulted audience chamber, or hall, which seems to be all that remains today. In truth, there is very little information on other structures within Ctesiphon itself.

Ctesiphon from the air

The final sack of Ctesiphon by Severus’ legions in A.D. 197 was a brutal affair, and one that ended that city and provided the death blow to the Parthian Empire.

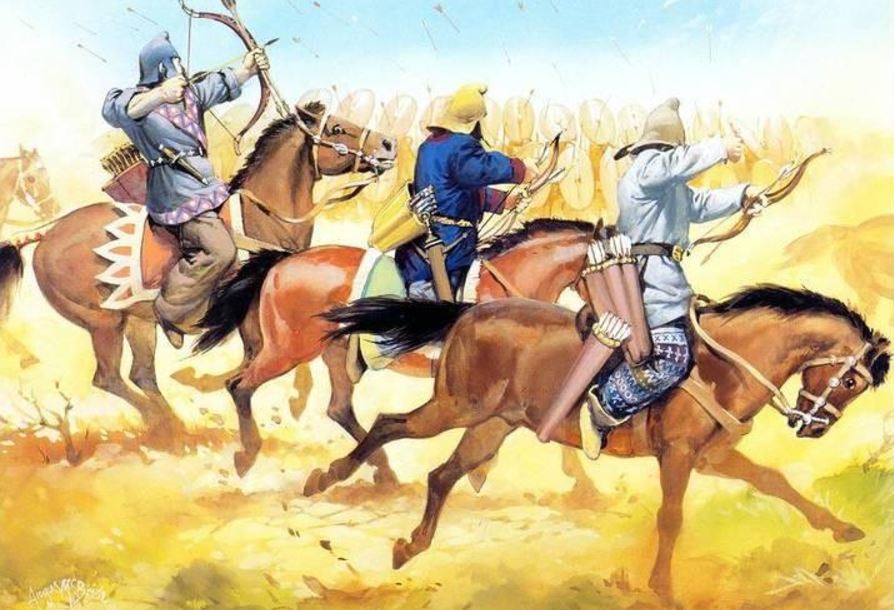

In A Dragon among the Eagles, the Roman attack on Ctesiphon is one of the major battle scenes which I had envisioned a long time ago. Imagine, almost thirty legions lined up on the other side of the river with the entire force of Parthian horse archers and heavy cataphracts awaiting them.

The Romans had to cross the river, gain a beachhead, and then push forward. In the end, Rome prevailed, but at great cost to the troops.

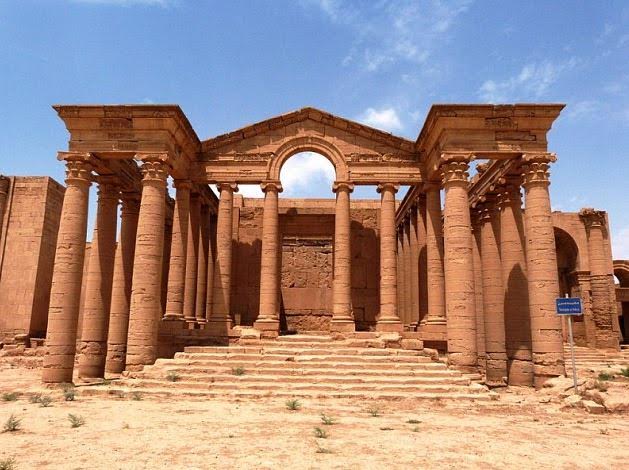

One would have thought that with the sacking of the Parthian capital, all would be finished, but there was another score for Rome to settle, another city to take – the desert city of Hatra.

As I write this, I have a pang of sadness, for while I was researching and writing about Hatra and the Roman siege there, extremist groups in the Middle East were in the process of the wonton destruction of this ancient heritage site. Writing this part of the book was indeed an odd experience.

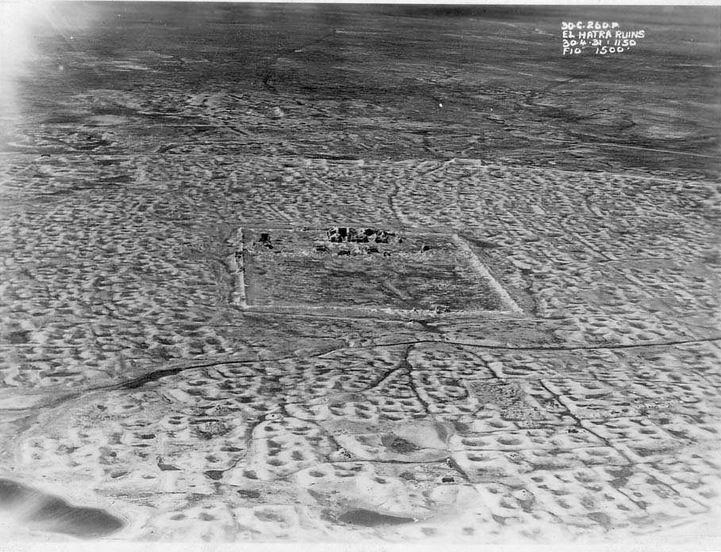

Hatra is located in modern Iraq, about 290 kilometers north of Baghdad, on the Mesopotamian desert, far from either the Tigris or Euphrates. It was built by the Seleucids, those Hellenistic giants we’ve heard so much about, around the third century B.C.

Hatra old survey aerial photo

It flourished under the Pathians too as a center of religion and trade during the first and second centuries A.D. What is fascinating about Hatra is the harmony and religious fusion it represented. This remote desert city was a place where Greek, Mesopotamian, Canaanite, Aramean, and Arabian religions lived peacefully side-by-side. And for 1,400 years it was protected and preserved by Islamic regimes, until it was destroyed in 2015.

It was the best-preserved Parthian city in existence.

Hatra before the 2015 destruction

When Septimius Severus turned his attention on Hatra after the fall of Ctesiphon, it was with a goal of doing what no other Roman, even Trajan, had been able to do.

It was personal too, for Hatra and its ruler, Abdsamiya, had supported Pescennius Niger against Severus in the civil war.

But there were a few reasons Hatra had withstood Roman sieges, including the two attempted by Severus in his Parthian campaign.

First of all, Hatra was remote, stranded out in the desert with its own water source within the walls, but none without. The nearest water was over forty miles in any direction. A legion could only march a maximum of twenty-five miles in one day. So, thirst for those laying siege was a big factor.

Then there were the walls – two of them. Hatra was protected by immense, circular, inner and outer walls, the diameter of which was 2 kilometers, or 1.2 miles. Along these massive walls were 160 towers, making this island fortress of the sand seas no easy target.

Hatra Map (with temples labelled)

At Hatra’s heart were the sacred buildings of the gods of various religions, gods whom many believed protected the city from attack.

The temples within Hatra covered a total of 1.2 hectares, and that area was dominated by the Great Temple of Bel which was about 30 meters high.

Hatra withstood two major attacks by Roman emperors, Trajan and Severus. Every time, Hatra’s walls, and her gods, turned Rome back.

Cassius Dio describes Severus’ last siege of Hatra:

He himself made another expedition against Hatra, having first got ready a large store of food and prepared many siege engines; for he felt it was disgraceful, now that the other places had been subdued, that this one alone, lying there in their midst, should continue to resist. But he lost a vast amount of money, all his engines, except those built by Priscus, as I have stated above, and many soldiers besides…

When the walls were breached, Severus gave the Hatrans time to consider surrender, as he respected the religious importance of the place, especially the temple of the Sun God. But the Hatrans were stubborn, and the troops were fed up:

Thus Heaven, that saved the city, first caused Severus to recall the soldiers when they could have entered the place, and in turn caused the soldiers to hinder him from capturing it when he later wished to do so [threat of mutiny].

Once again, Hatra resisted being conquered by Rome, making it the only place Severus’ legions were not able to take.

One of Hatra’s many magnificent temples

It is sad that, in light of the events of 2015, it seems Hatra’s gods finally deserted it.

To see more of Hatra before its destruction, CLICK HERE to watch the UNESCO video.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this march with the legions! In the next post, we’ll be going somewhere more civilized – the City of Alexander the Great!

This past week has been a good one for A Dragon among the Eagles, for in the UK it became an Amazon #1 Bestseller in three categories, including Historical Fantasy. It is also climbing in the Amazon US charts too, so thank you to everyone for supporting the book!

For those of you who prefer to read paperbacks, A Dragon among the Eagles is now available in trade paperback format from either Amazon or Create Space.

And as ever, thank you for reading.

The World of A Dragon among the Eagles – Part II – The Imperial Roman Legion

The world in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place, and with which the main characters are concerned, is also the world of the Roman legion.

Indeed, the imperial Roman legion figures largely in the entire Eagles and Dragon series, and so, I thought it good to do a brief introduction of the make-up of the legion at the time the book begins in A.D. 197.

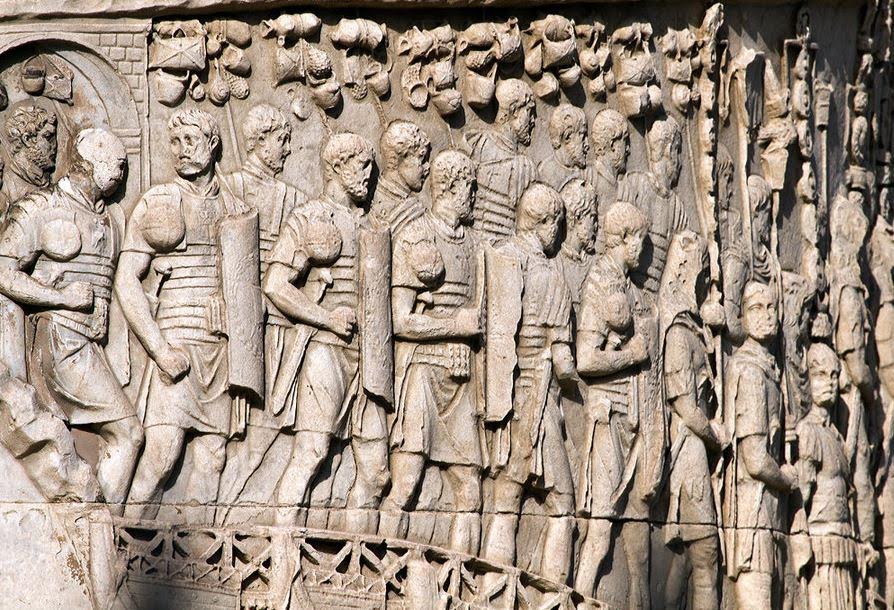

Roman legionaries on Trajan’s column

At this time in the history of the Roman Empire, the Roman legion is a well-oiled machine. It, and its troops, had been perfected after centuries of warfare, of trial and error, victory and defeat.

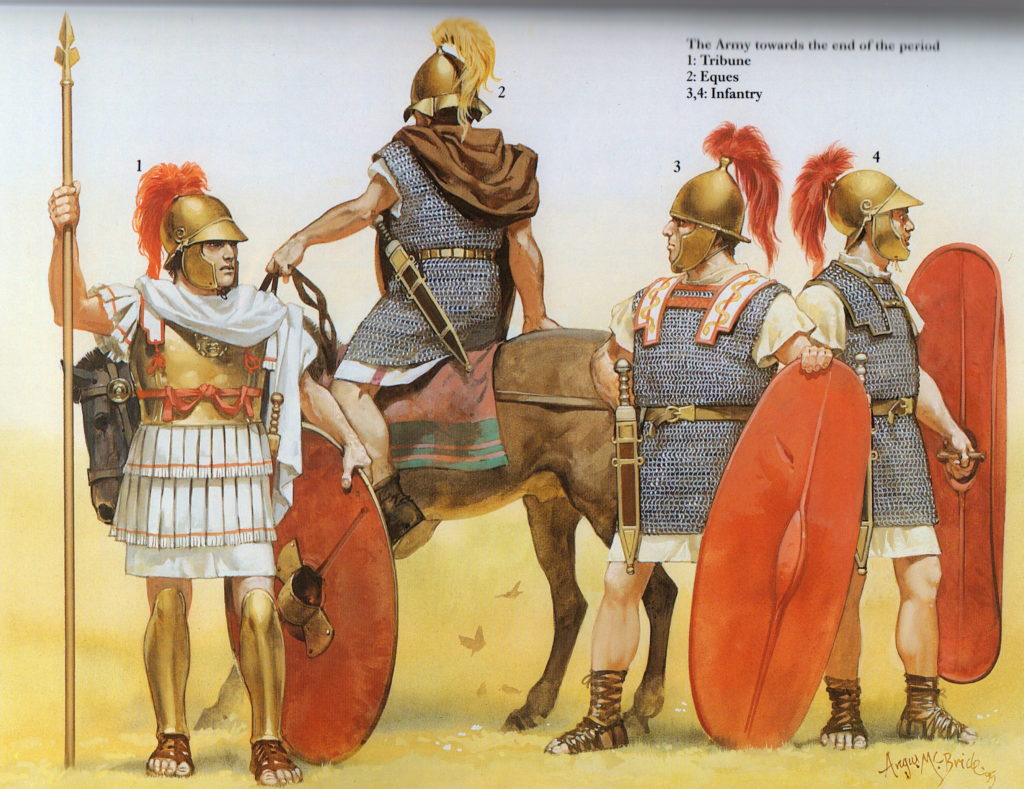

This army, the army of the Principate, is quite different from that of the Republic. It used to be that Roman legionaries were required to meet minimum requirements of possession and wealth in order to qualify for service in the ranks.

Republican Roman troops (illustration by Angus McBride)

This all changed in 107 B.C when Caius Marius was elected consul and sent to Numidia to continue the war there. However, Marius was denied the right to raise new legions in Africa, permitted only to take volunteers with him.

Of course, Marius took advantage of this, and in a move no other had taken, he appealed to the poorest classes of citizens who became known as the capite censi.

These ‘head count’ citizens were enthusiastic about joining the legions and the new opportunity for a livelihood that it presented them with. They became the backbone of the Roman Legion, and from that time onward the link between military service and property was done away with. They need only have been citizens.

Gaius Marius among the ruins of Carthage (Joseph Verner 18th century)

Marius made many reforms to the Roman army which I won’t go into here, however, his move contributed to the creation of a permanent, full-time citizen army, a self-sufficient fighting force of well-trained men with standard-issue equipment, food and lodging. They carried everything they needed on the march on their own backs, including weapons, spikes for palisades, pots, pans, and pick-axes for digging fortifications.

Marius’ Mules – Re-enactors marching in full kit

Because of all the kit they carried in the field, they became known as ‘Marius’ Mules’.

The average kit for a rank-and-file soldier in the imperial legions included hobnail sandals known as caligae, a standard tunic, a leather belt or cingulum, a lorica segmentata which was a breast plate made up of individual iron strips, a helmet, cloak, gladius (short sword), pugio (dagger), a pilum (javelin), and a scutum (shield).

Re-enactor in Roman Legionary outfit

In A Dragon among the Eagles, there is mention of the various ranks and units that make up the legion, so I think it a good idea to cover the basics now.

The smallest unit of men in the imperial legion was a contubernium which consisted of eight men who shared a tent, or barrack room. These men marched, fought, lived, and cooked together.

Then there was the century. This is probably the most well-known unit of men. It consisted of 10 contubernia, and was run by a centurion with a standard bearer and an optio beneath him.

The centurion was usually a career soldier, and a harsh task-master. He wore different armour that was chain mail, usually with a harness decorated with phalerae, decorative discs that represented awards he had been given. The crest of a centurion’s helmet was horizontal, and he carried a short wooden staff called a vinerod, which gave him the right to strike his citizen soldiers in the interests of discipline.

Re-enactor dressed as a Centurion (Wikimedia Commons)

There are stories about a particular centurion in the imperial legions whose nick-name was ‘give me another’ because he was constantly breaking his vinerod over the backs of his men!

Centuries of eighty men were the most flexible military units in the legion. They numbered enough to go on patrol, or building duty, and could manoeuvre effectively in battle.

Now, the next unit of the legion was the cohort.

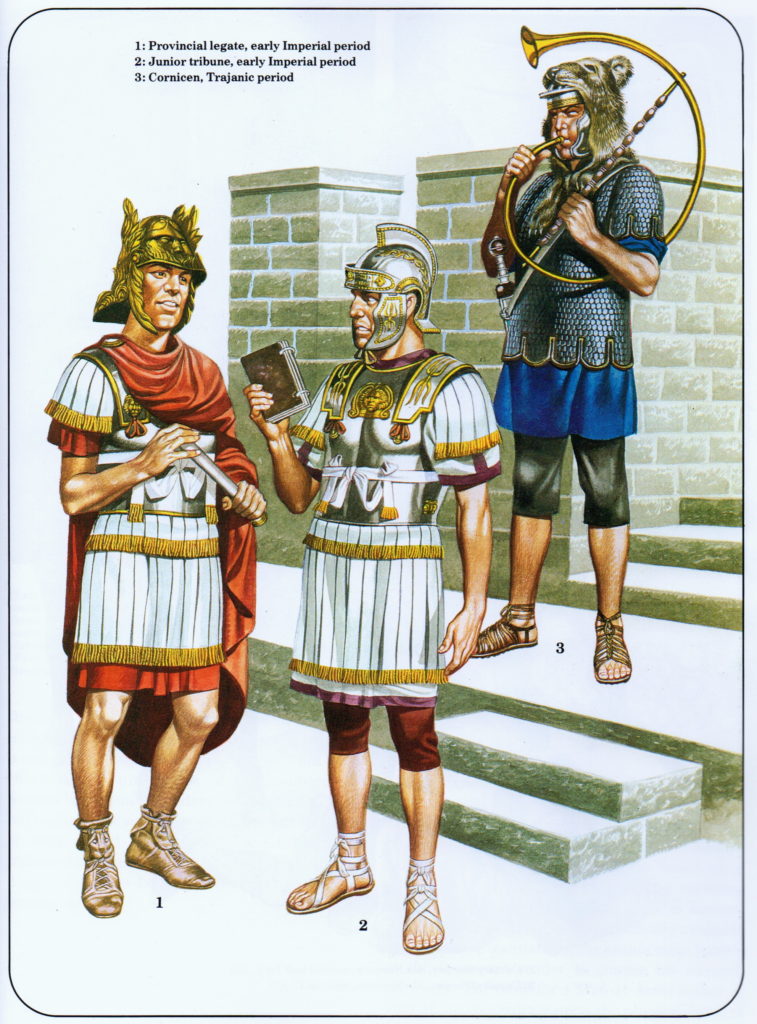

The imperial cohort was made up of 480 men, and consisted of six centuries let by an Equestrian tribune. The first cohort of a legion, however, was led by a Patrician tribune.

Officers of the Imperial Roman Legions (illustration by Ron Embleton)

Finally, there were ten cohorts in a legion which brought the average number of troops in the imperial legion to 5000.

The commander or general of an entire legion was known as the legatus legionis, or legate commander. This person was usually a senator, just like the patrician tribune who was his second-in-command. The third person of overall authority in the legion was the camp prefect, or praefectus castrorum. The latter was often a career soldier, perhaps a former centurion who had been promoted, and was responsible for much of the legion’s administration and logistics.

There were many other minor positions within the legions such as duplicarii, men who received double pay for skills such as engineering, or the building of siege equipment, as well as benificari, those who were aides to the legate or other officers, and who were excused for intense labour such as the digging of ditches and erecting palisades.

Roman legionary standards with an image of Emperor Severus and his family

We must not forget the standard bearers who made up the imperial legion. These included the vexillarius, the person who carried the vexillum standard of each unit, the signifer, the soldier who carried a century’s standard and wore a wolf or other pelt over his helmet. There was the cornicen, the trooper who carried the cornu, the round horn used to rally the troops and give commands, as well as the imaginifer of the legion, the trooper whose task it was to carry the image of the emperor before the legion.

Probably the most important standard bearer was the aquilifer, the man whose solemn duty it was to carry the legion’s golden eagle, the aquila, into battle. This man was to protect the legion’s eagle at all cost, for it was the ultimate disgrace for a legion to lose its aquila to an enemy.

Re-enactor dressed as an Aquilifer

Along with the 5000 regular troops that made up an imperial legion, there were often alae, or auxiliary units, attached to the legion. These were usually units of 120 cavalrymen who acted as scouts and supported the legion on the march. They were often made up of foreign troops who had been brought into the Roman ranks such as Sarmatians, Numidians, or Scythians to name a few.

Ala units might also consist of skirmishers such as Cretan or Balearic slingers, but most often they were cavalry.

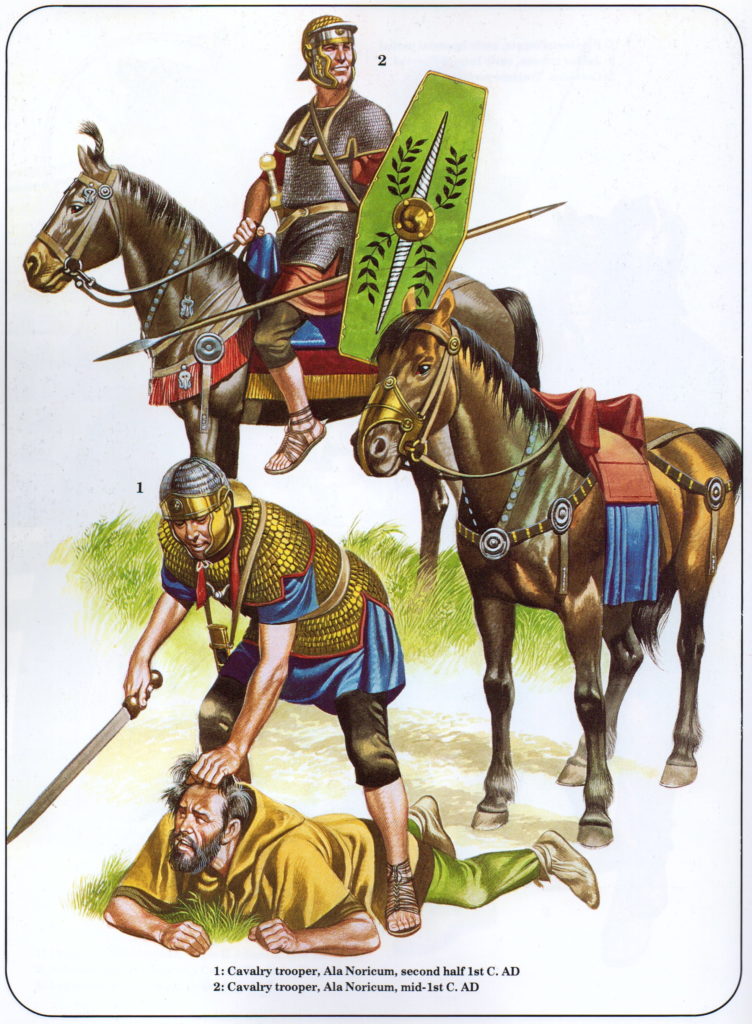

Auxiliary Cavalry troops (illustration by Ron Embleton)

The imperial Roman legion was one of the most effective fighting units of the ancient world, and it is no wonder that the Empire covered so much of the known world by the time in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place.

Disciplina, the goddess personification of discipline, was something that was taken very seriously. If a soldier obeyed her and remembered his training, he would survive the direst of circumstances.

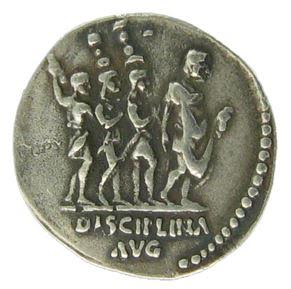

Roman coin showing stardard bearers and the world ‘Disciplina’ – second century A.D.

When the legions marched in the field, every night they dug in, every trooper going to his assigned space to dig ditches, pile up ramparts, and raise the palisade around the entire camp.

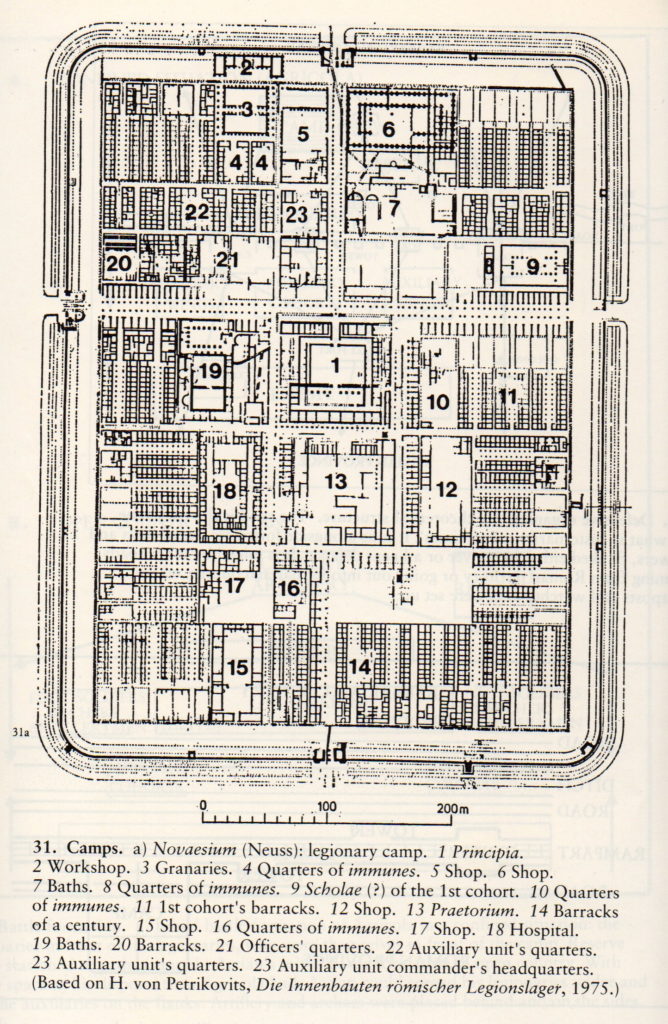

Tent and command centre, the Principia and Praetorium, tribunes’ tents, stables etc. were always in the same position, the streets set out in the same grid every time. So, whatever happened, a Roman soldier knew where he was, and what he had to do.

Every morning, when they would break camp, they would take down the work of the previous evening, which they had done after a twenty mile march, so that the enemy could not make use of their fortifications.

Plan of a typical legionary fortress (from The Imperial Roman Army by Yann Le Bohec)

It was hard work, but the imperial legion gave opportunity to the poorer classes of Roman citizens and allowed them to make something of themselves, if not at least be clothed and fed at the state’s expense.

In return, the men of the legions bled for Rome as they extended her borders into the world.

A Dragon among the Eagles takes place during the Severan invasion of the Parthian Empire, one of the biggest thorns in Rome’s side for over two hundred years.

In A.D. 197, Septimius Severus set out with one of the largest invasion forces in Rome’s history, made up of a titanic 33 legions.

The stage was set for one of the greatest military campaigns in Rome’s history.

In the next post, we’ll look at this powerful enemy and the tactics they used in battle against the legions.

Until then, check out this great video that illustrates the make-up of the Roman legion.

Thank you for reading!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wCBNxJYvNsY