We’re changing pace for this next blog post, leaving the world of Roman Britain behind for the moment.

Over the holiday season, I managed to watch a bit of television – something that I don’t really do that often.

Like most people nowadays, I headed over to Netflix to see if anything caught my eye, and sure enough, there was a title that promised some great historical drama: MEDICI.

The show was only eight episodes, and certainly called to my love of history, Tuscany, and Italy in general. So, I sat down to watch.

I was not disappointed.

If you want a peak at Florence and the era that really gave rise to the Italian Renaissance, this is something you should watch.

Tuscan landscape

I love Florence, and have been there a couple of times.

It’s one of the most beautiful, culturally-rich cities I’ve seen, and I would go back there in a heartbeat.

If you’ve been there, you’ll know what I mean when I say that this city is for roaming and enjoying. From the Duomo and Baptistery, to the Ponte Vecchio, the Piazza della Signoria and the Palazzo Vecchio, to the hallowed halls of the Uffizi Gallery where countless masterpieces hang, there is so much to see and do (and eat!) in this beacon of art and culture on the banks of the Arno.

Piazza della Signoria (by Giuseppe Zocchi)

When anyone thinks of Florence, they think of late medieval and Renaissance art and architecture, of the greats of history such as Dante, Da Vinci, Machiavelli, the Medici and many more.

When one thinks of Florence, the Roman Empire is not usually the first thing that comes to mind.

The truth is that Florence was originally established as a Roman camp. It was called ‘Florentia’, and beneath the façade of Renaissance grandeur that we see today, this city has Roman roots.

Today, we’re going to take a brief look at the Roman origins of Florentia.

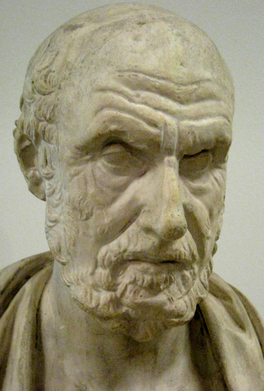

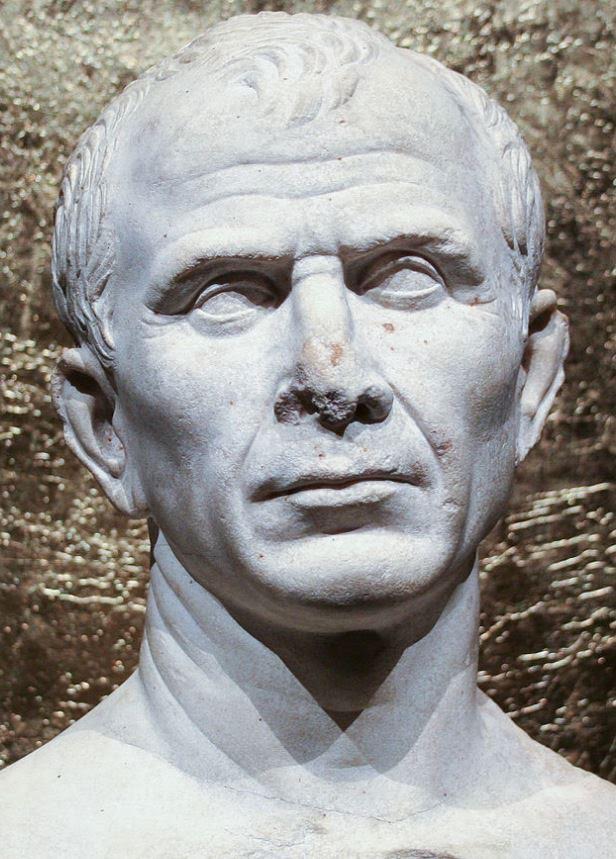

Julius Caesar

Before the Romans overtook this land, the Etruscans ruled here, and they had established a centre at Fiesole, up the hill a short distance from the Arno River.

The Roman settlement of Florentia was established, most agree, by Julius Caesar around 59 B.C. as a military camp intended to guard the ford where the Via Cassia, the main road through Etruria, crossed the river.

It was just prior to this that Catiline led a rebellion against the Republic, and it seems that perhaps he, and many of his supporters holed up in nearby Fiesole.

Around 60 B.C., Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer, one of Rome’s consuls at the time, marched out to meet Catiline’s forces.

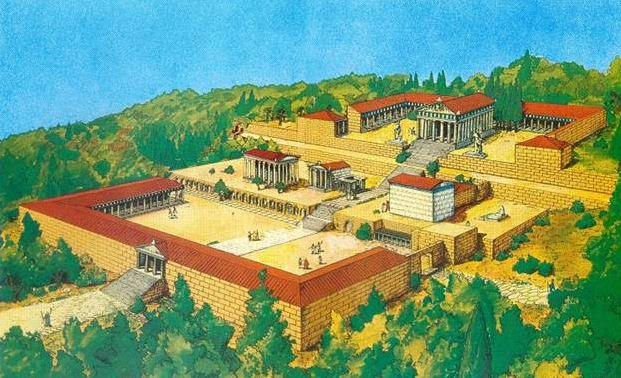

Roman ruins at Fiesole

Now, here is where the story gets a bit blurry.

There appears to be some confusion around the origins of the name, ‘Florentia’.

Some believe that the word stems from ‘fluente’ which may refer to the flowing of the Arno river itself.

However, there is another, more romantic tale regarding the foundation of Florentia.

There is a story that accompanying Metellus against Catiline’s forces in Fiesole was a praetor or other high-ranking person named ‘Fiorinus’ who led several actions against Catiline and his conspirators.

This Fiorinus apparently fought very bravely, but was killed in an attack on the Roman camp along the Arno.

Why was this man, Fiorinus, important?

Well, some believe that Julius Caesar, who joined the battle against Catiline at Fiesole shortly thereafter, named Florentia after Fiorinus.

Here, Machiavelli writes about the two different theories about the origins of the name:

There are various opinions concerning the derivation of the word Florentia. Some suppose it to come from Florinus [Fiorinus], one of the principal persons of the colony; others think it was originally not Florentia, but Fluentia, and suppose the word derived from fluente, or flowing of the Arno… I think that, however derived, the name was always Florentia, and that whatever the origin might be, it occurred under the Roman empire, and began to be noticed by writers in the times of the first emperors.

(Niccolo Machiavelli, History of Florence and the Affairs of Italy)

The Discovery of the Body of Catiline (1871) Alcide S … allery of Modern Art, Florence) Wikimedia Commons

As with many ancient tales, it’s difficult to ascertain the truth.

The important thing, and that which is more generally agreed upon, is that Florentia was established as a camp by Julius Caesar, who later made it a colonia for veterans of his legions.

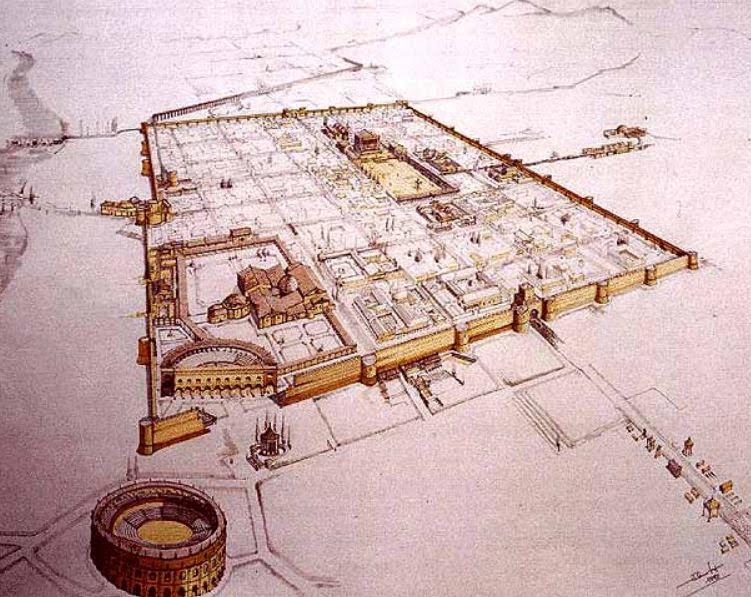

When we walk around Florence today, it is clearly a medieval and Renaissance city. However, if you know where to look, you can see the remains of Colonia Florentia.

Main roads of Roman Florentia

In the image above, you can see the main Roman roads on today’s Florentine streets.

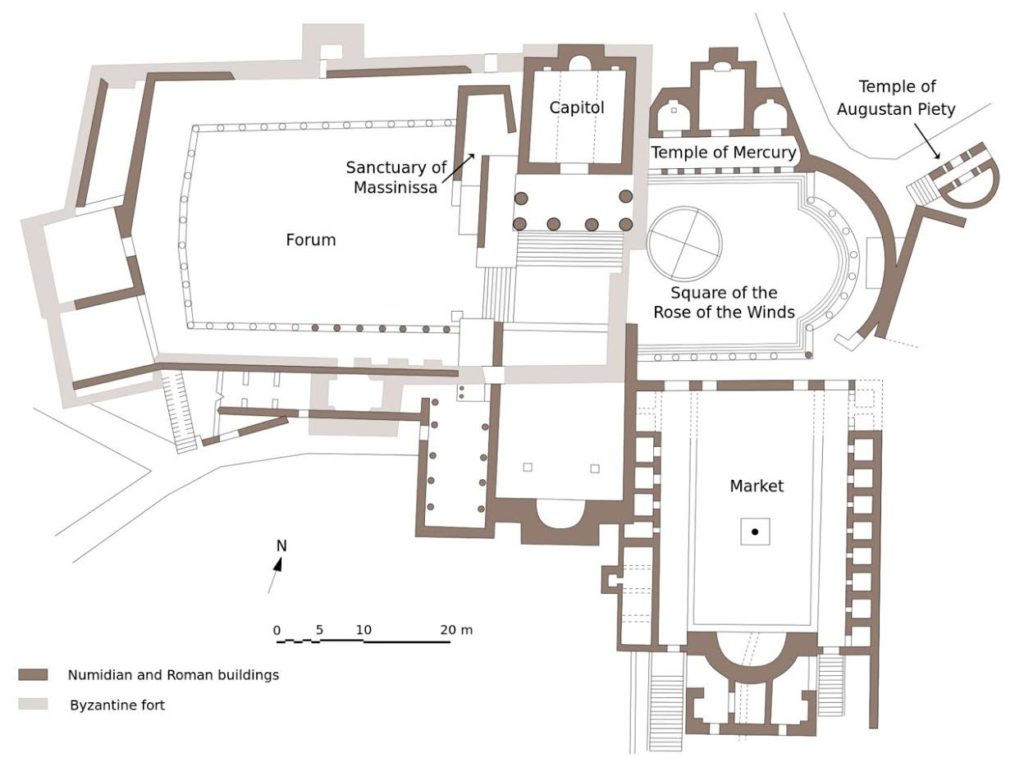

The main north-south street of Florentia, the cardo maximus, followed the line of the Via Roma today. On the east-west axis, the former decumanus maximus ran the length of the current Via degli Speziali, and the Via degli Strozzi.

Like all thriving Roman settlements, the beating heart of the city was the forum, and Florentia’s was located in what is now the Piazza della Republica.

Piazza della Repubblica – the Forum of Florentia (Wikimedia Commons)

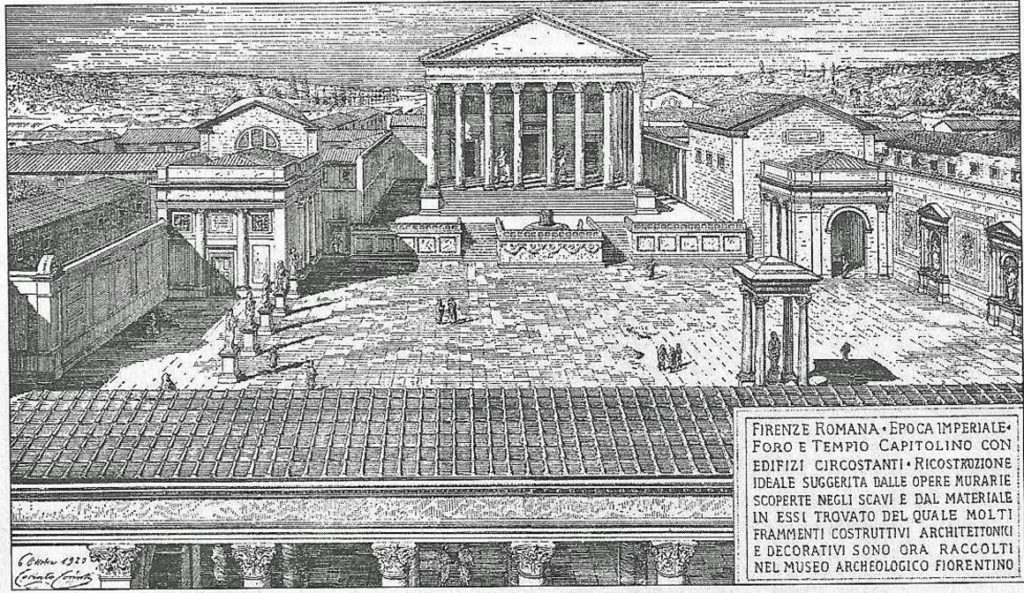

Apart from being the commercial centre of Florentia, the forum was also the administrative and religious centre of the colonia. There was no antique carousel, as there is today, but there was a temple to Mars, as well as a temple to the Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva.

The curia itself, which was also located in the forum, was where the town council, made up of decurions, met to discuss the business of the colonia. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the governing body of Florence, known as the Signoria instead of the Curia, met in the Palazzo Vecchio, located in the current Piazza della Signoria.

Artist impression of the Forum of Florentia

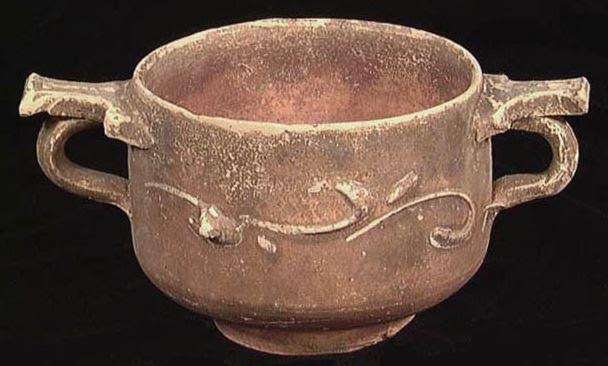

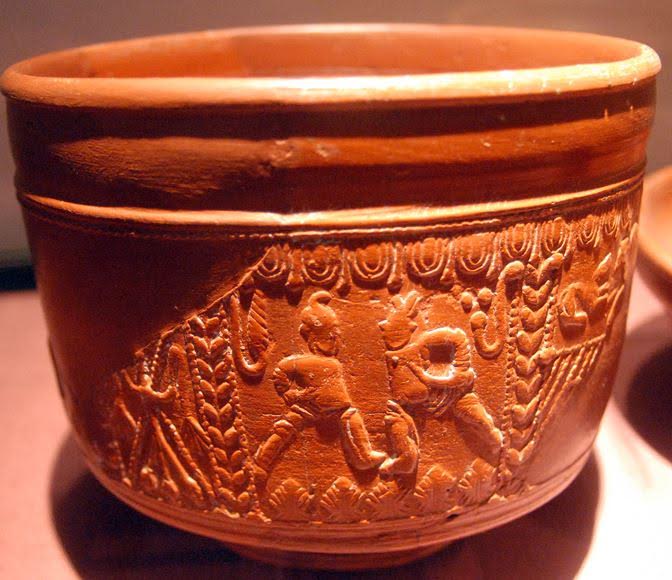

Archaeologists, over time, have discovered other Roman structures beneath the streets of this city, ghostly shades of Florentia’s past.

There were Roman baths located outside the south wall of the original fort along the current Via delle Terme. After all, what Roman settlement did not have a bath?

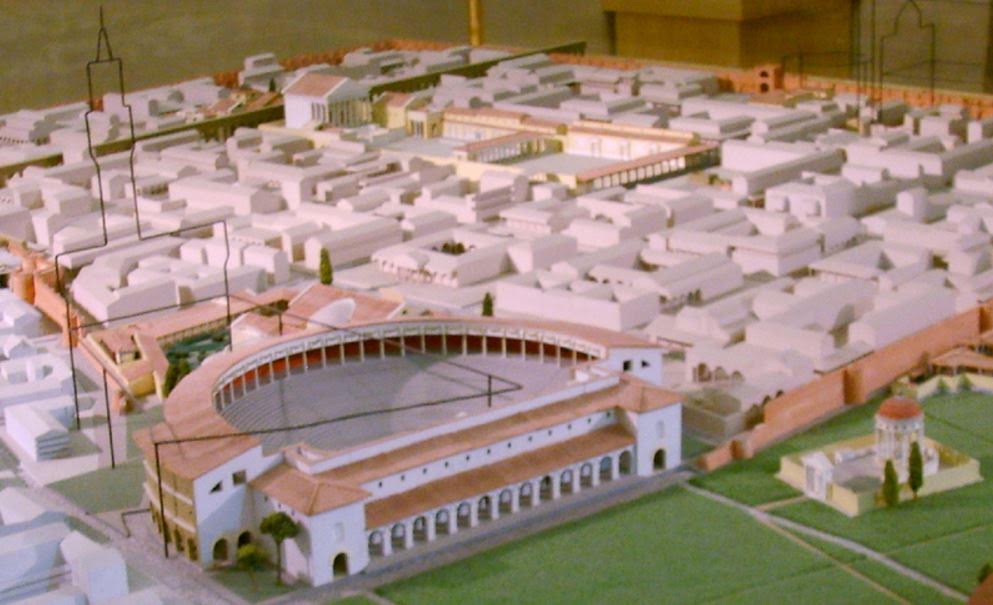

Model of Roman Florence (from the southeast)

The same goes for a theatre.

As if echoing the artistic future of this great city, Florentia had an 8-10 thousand seat theatre in the southwest precinct of the colonia. The Palazzo Vecchio is partially built over top of this.

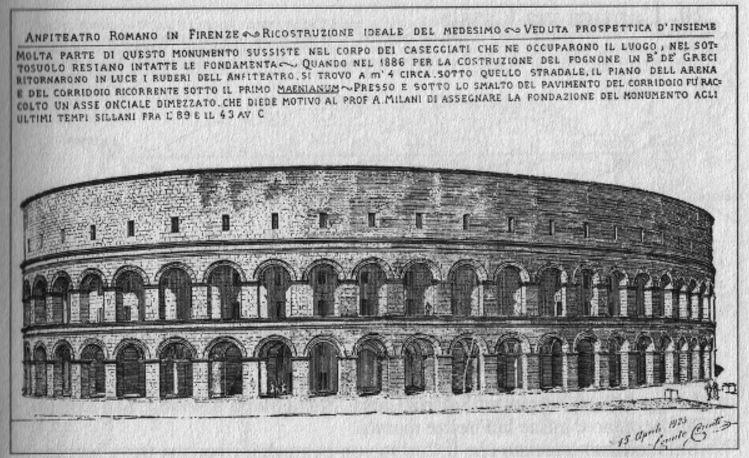

Reconstruction of Florentia’s Theatre

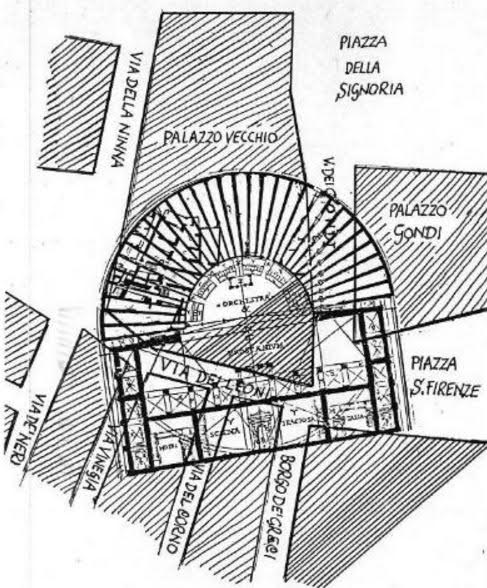

If you walk behind the Palazzo Vecchio today, and cross Vie dei Leoni, you will find yourself outside the line of the original Roman walls.

Along Borgo dei Greci lies Piazza san Firenze where, during the Roman period, there stood a temple of Isis, the Egyptian goddess whose cult had become quite popular across the Roman Empire.

Continue on Borgo dei Greci to the curve of Via Bentacordi and you will find yourself on the site of the amphitheatre of Florentia, just near the current Piazza Santa Croce.

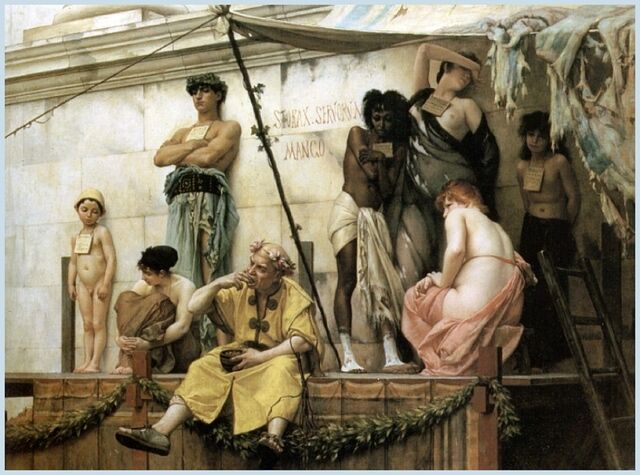

The amphitheatre was, of course, where the troops would have drilled and paraded, and the populace would have enjoyed gladiatorial combats and other entertainments popular in the Roman world.

Reconstruction of Florentia’s Amphitheatre

Sadly, most of Roman Florentia is hidden from our eyes, but there are a few other places where the Roman past is hinted at.

For example, just before the Bargello, outside what was the ancient east wall, there is a brass half-circle in the street that marks the foundation of a Roman watch tower. Archaeologists have also found the remains of cloth dying vats which indicate that Florence’s pre-eminence as a textile-producing centre may have originated much earlier than in the Middle Ages.

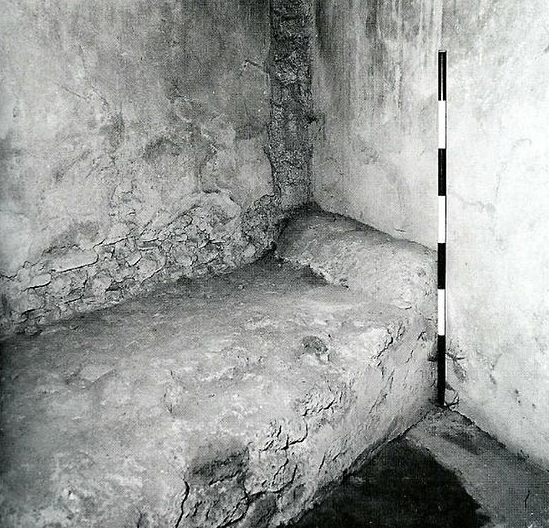

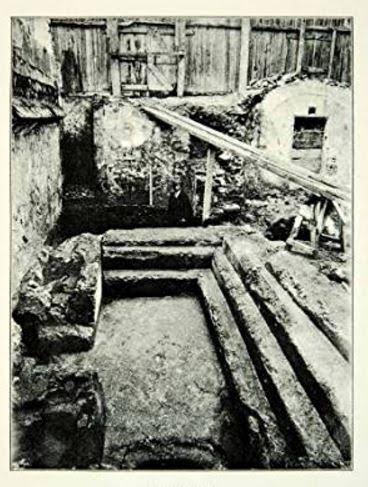

Remains of a frigidarium in Florance

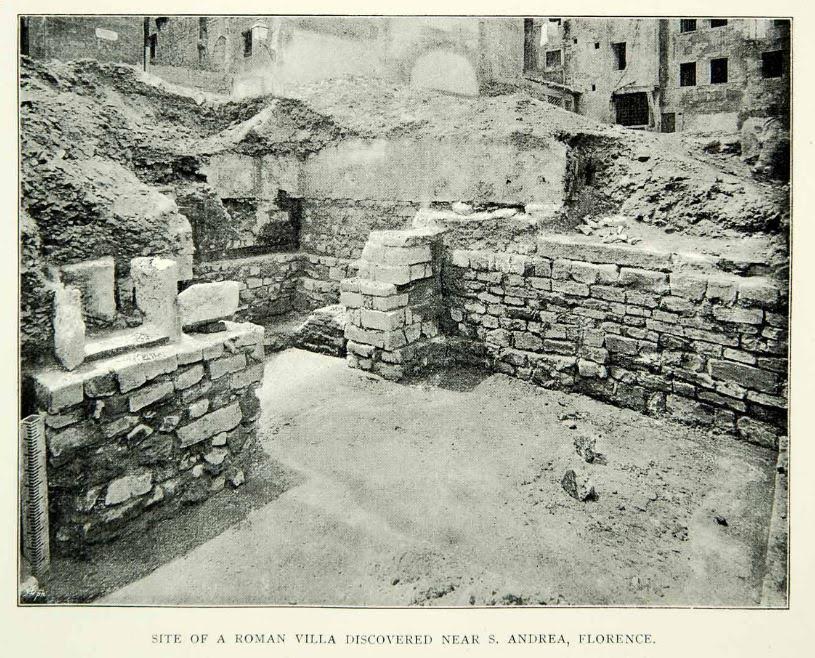

There are other remains dotted around the city too – the remains of baths, private villas and homes – but most are inaccessible, or require permission from property or business owners to view.

Beneath Florence’s most prominent monument, Santa Maria del Fiore, or the ‘Duomo’ as it is known, was the site of an ancient Roman temple and other buildings (both Roman and early Christian). These can be viewed in the crypt of the Duomo, which was opened to the public, I believe, in 2014. Sadly, that was after I had visited!

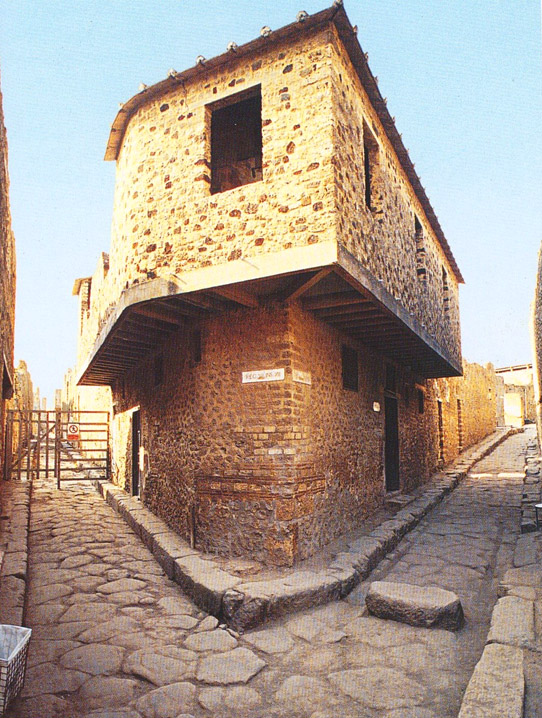

Part of a Roman Villa near San Andrea, Florence

And finally, across from the entrance to the Duomo, is the famous Baptistery of San Giovanni, which was built in the 11th century. This magnificent, octagonal building is one of the oldest standing buildings in Florence today, and it is believed that much of the marble facing used to decorate the walls of the Baptistery was taken from the ancient buildings of Roman Florentia.

Artist impression of Roman Florentia

I often daydream about the places I’ve travelled to, and Florence is certainly at the top of that list – the history, the art, the architecture, the food, and the surrounding Tuscan countryside are the stuff of dreams.

If you ever get the chance to visit Florence, or to go back, by all means, soak up the Medieval and Renaissance worlds to your heart’s content. Those are the reasons to go in the first place!

However, while you’re strolling the streets, enjoying your gelato from Festival del Gelato or any other gelateria there, take a few moments to think about where this magnificent city of art and culture came from.

Florence from Fiesole

The Etruscans had built on the hill, away from the river, but it was the Romans who set up camp here. And whether it was erected by Julius Caesar or not, or named after a fallen hero of Rome, the Florence of today owes its past to the Florentia of the ancient world.

The remains of Florentia may not be easily visible now, but they are there, in the shadows cast by ancient Rome.

Arrivederci e grazie!

Ciao from Firenze!

Ok, so that photo is a few years old