Scotland

Oh, Picts!

We’re heading into the wilds of Caledonia in this week’s post.

I wanted to discuss a topic that is often neglected although it is very interesting: the Picts and Pictish art.

As I’ve been packing for a move, I discovered some of my old photos from my days in St. Andrews, Scotland. I came across a packet of prints from an outing with some of my MLitt colleagues to visit Pictish sites in Angus and Perthshire.

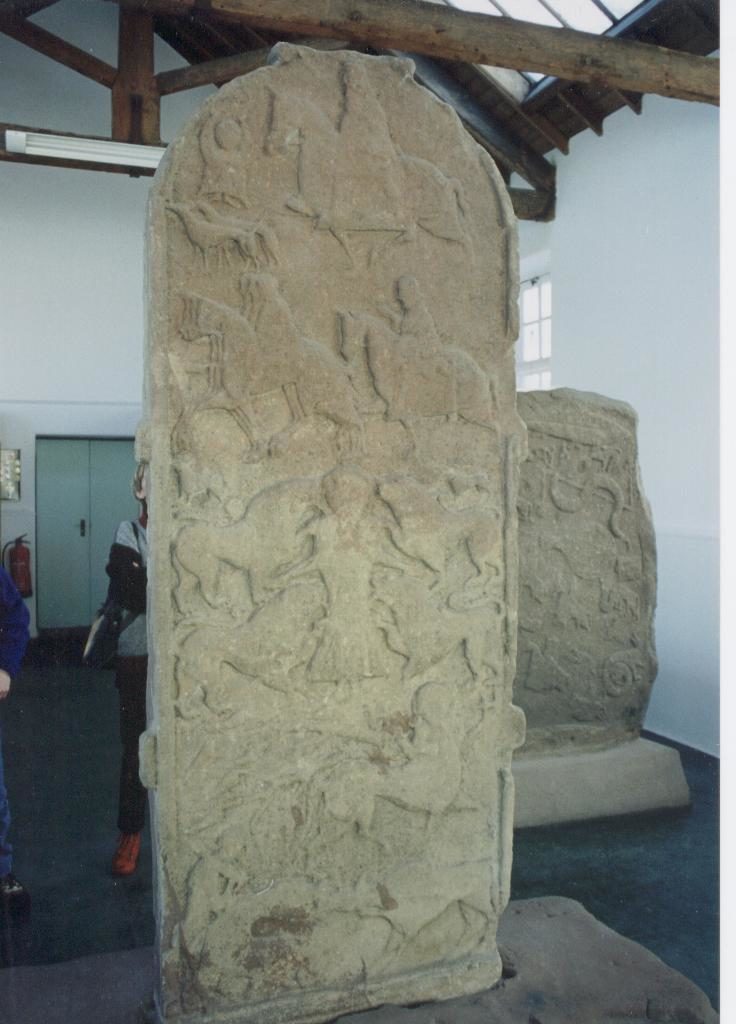

The main attraction for us was the wide array of ornate carvings on several Pictish gravestones, most of which are maintained by Historic Environment Scotland at the Meigle Museum which is itself an old school house on the A94 Coupar Angus to Forfar road (for those of you who are interested in visiting). This little museum is a true gem and well worth a visit.

Before looking at the carvings however, I suppose I should answer one simple (or not so simple) question. Who were the Picts?

In brief, they are the direct descendants of the Caledonii, the blanket name given to those tribes who lived in the lands north of the Firth of Forth.

We hear about the latter in relation to the Roman invasion of what is now Scotland by Agricola in AD 79. The action-packed movie Centurion, with Michael Fassbender, which came out in 2010, deals with Agricola’s operations north of the Firth of Forth and the presumed disappearance of the Ninth Legion. In the film, the Caledonii/Picti are portrayed as a society run by a warrior elite, the members of which paint themselves with blue woad. The film is very entertaining, if not violent, but the best thing is that it was filmed where much of the history presumably took place. It’s worth a gander for that, if anything.

But were the Picts simply a mass of blue barbarians as they’re so often portrayed? Likely not.

Contrary to the usual portrayal, the Picts were not simply one enormous group living and fighting north of the Antonine Wall. They were indigenous Celts and the term ‘Picti’, like ‘Caledonii’ or ‘Maeatae’ is more of a blanket term that included approximately twelve Celtic tribes north of the Forth and Clyde rivers. These were recorded by the Roman geographer Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. Because of the military threat posed by Imperial Rome, the Celts in the area amalgamated into two larger groups. The Caledonii and the Maeatae and, in turn, came to be later referred to as ‘Picti’.

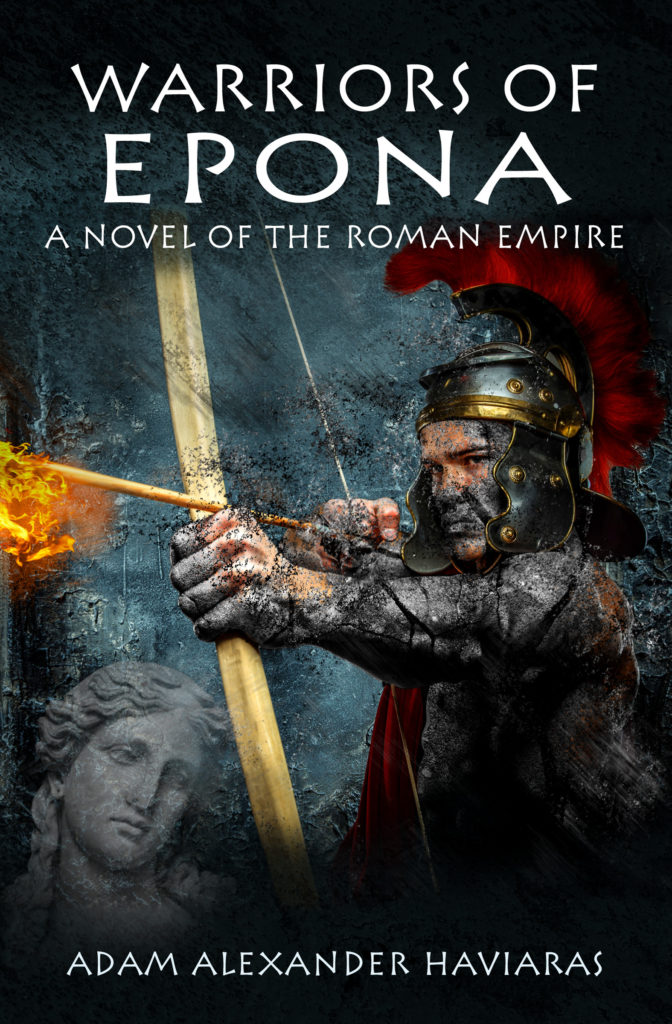

The tribal federation survived the various Roman incursions (the last one being the Severan invasion of Scotland in the early 3rd century – the setting for Warriors of Epona). As a result the Picts were able to develop mechanisms of kingship and by the 6th century there was a Pictish kingdom.

In Pictish art, there are certain recurrent symbols such as those found on the Aberlemno stone including the ‘serpent’, the ‘double-disc’, the ‘crescent’ and the ‘Z-rod’. When I visited the Meigle museum I was struck immediately by the amount of Christian imagery, having had in my mind typical images of paganism when it came to the Picts. The presence of crosses and other Christian images is due to the conversion of the Picts to Christianity after the Irish abbot of Iona, St. Columba, ventured into ‘Pictland’ in AD 565. Columba met the Pictish king, Bridei son of Maelchon in a fortress near the River Ness and thus began the conversion of the Picts, a process that was complete by about AD 700.

The Pictish symbol stones are one of the most important sources for information about the Picts, and the symbols, common from one end of Scotland to the other, were widely understood by all the tribes. Now, however, we know very little of their actual meaning except that they functioned as memorial stones or territorial boundary markers.

The church yard at Meigle contained a large number of Pictish stones, implying that Meigle was itself a very important centre of burial for the Pictish church and under the patronage of the kings of the Picts. Eventually however, Pictish rule, which had survived the onslaught of Rome in Late Antiquity, was taken over by the Gaelic-speaking settlers of Dalriadia (or ‘Dal Riata’ – modern Argyll) which led to the reign of the Scots King, Kenneth mac Alpin and his subsequent dynasty.

Before we bid farewell to the Picts however, there is an interesting Arthurian connection with Meigle and one of the Pictish stones (cross-slab no.1).

On entering the graveyard at Meigle, there is a grassy mound known as Vanora’s Grave. Local tradition has it that Vanora was actually Queen Guinevere, the wife of Arthur. Vanora was abducted by the Pictish king, Mordred, and held captive near Meigle. When she was returned to her husband after this forced infidelity, she was sentenced to death by being torn apart by wild beasts, hence the scene of Vanora’s death on the back of cross-slab no.1. Her remains were buried at Meigle.

Tradition also says that Vanora (and Guinevere for that matter) was barren and it is believed that any young woman who walks over her grave risks becoming barren herself. True or not, this is yet another interesting anecdote of history and legend.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post. Once more, if you ever get the chance to visit Meigle’s museum and some of the stones in the surrounding area, it’s well worth it.

If Picts are your thing, then you may also wish to take a look at the map and pamphlet of Pictish sites released by the Angus Council by CLICKING HERE.

Thank you for reading!

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part IV – Battle Line: The Gask Ridge Frontier

When most think of the Romans in Britannia or Caledonia, almost always the first thing that comes to mind is Hadrian’s Wall.

But there is another frontier that many people may not know of. You may have heard of some of the forts or camps that make up a part of this frontier, such as the legionary base at Inchtuthil.

Roman re-enactor watching the frontier

I’m talking about a line of forts and camps known as the ‘Gask Ridge’.

Research on this particular frontier has been less in depth than either the Antonine or Hadrianic walls. However, over the past ten years or so, the Gask Ridge has received its due attention thanks to the efforts of Birgitta Hoffmann and David Woolliscroft who have spearheaded the Roman Gask Project.

The importance of this frontier cannot be over-emphasized.

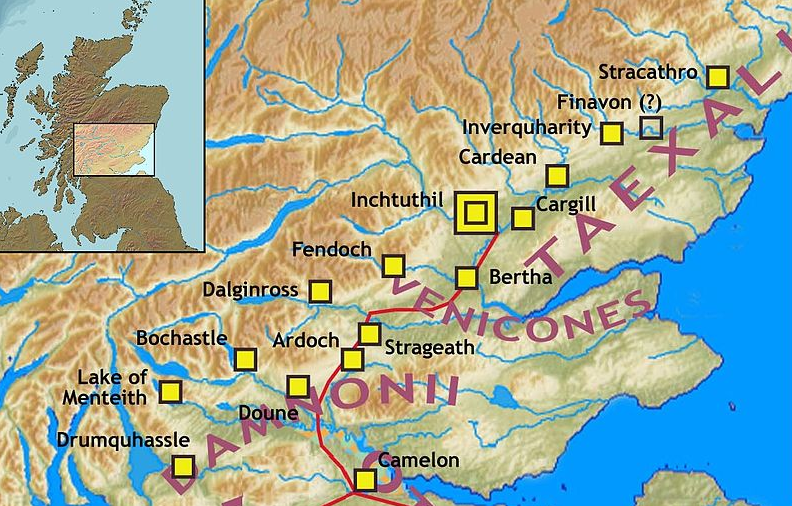

Gask Ridge Forts (Wikimedia Commons)

The Gask Ridge frontier has seen action in every one of Rome’s Caledonian campaigns and some of the research even shows that it was the first chain of forts in northern Britain, predating the other walls.

Some believe it is the first such frontier in the Empire!

It consists of a long line of forts, watchtowers, and temporary marching camps that run from the area of Stirling, on the Antonine Wall, past Doune, along the edge of Fife and up into Angus, all the way to Stracathro.

This is a very impressive line of defence built by Rome with the intent of holding the Caledonii at bay, and separating the highlands from the flatter plains leading to the North Sea.

Artist Impression of Caledonian Warriors

In writing Warriors of Epona, the trick was finding out which forts may have been in use during the campaigns of Septimius Severus in the early 3rd century A.D.

The forts of the Gask Ridge were used mostly during Agricola’s campaign in the late first century, and then by Antoninus in the mid-second century.

Roman road along Gask Ridge in Perth and Kinross

The Romans definitely knew how to pick a strategic location along the perfect line of march, so it’s likely marching camps would have been reused in later campaigns. But some of that is supposition.

One site that we know was built as part of the Severan campaign was the legionary fort at Carpow, on the banks of the Tay. With a large part of a legion stationed there, the supply chain could be maintained by sea with Roman galleys coming up the Tay. It was also at this time that some believe the first Tay Bridge was built when Severus ordered the creation of a boat or pontoon bridge to the Angus side of the river.

Aerial view of Horea Classis site (Carpow)

Carpow was a large base of operations intended to make a statement – Rome was going to stay this time! Severus was a military emperor who liked to prove his point. He was in Caledonia to finish what other Roman emperors had started, just as he did in Parthia.

The Gask Ridge plays a key role in Warriors of Epona, especially the forts that may have seen re-use during the third century, among them the forts at Camelon, Ardoch, Fendoch, and Bertha, the latter being where Lucius Metellus Anguis establishes his forward base.

Ardoch Roman camp remains

Of course, one of the exciting things about writing historical fiction, after the research, is filling in the gaps and exploring possibilities.

Because research on the Gask Ridge is relatively new, we can certainly look forward to learning more from Hoffmann, Woolliscroft, and everyone else on the Roman Gask Project team who are leading the charge to further our knowledge of this ancient frontier.

One thing that I have discovered over the years is that even though the history and research are very important, at the end of the day, in fiction, the story must come first.

With Warriors of Epona, history and story have come together nicely, and that has been pure magic!

Cheers, and stay tuned for the fifth and final part of The World of Warriors of Epona.

Aerial view of Fendoch and the Sma’ Glen from the south with the fort on the low plateau in the right foreground.

If you are interested in reading more about the Roman Gask Frontier, or about the Romans in Scotland, do have a look at the following resources:

The Roman Gask Project: http://www.theromangaskproject.org/

Rome’s First Frontier: The Flavian Occupation of Northern Scotland. By D. J. Woolliscroft and B. Hoffman. Pp. 254. ISBN: 0 7524 3044 0. Stroud: Tempus. 2006.

Warriors of Epona – Eagles and Dragons Book III is one sale now!

But remember! If you have not yet read any of the Eagles and Dragons novels, and if you want to start off on an adventure in the Roman Empire, you can pick up the #1 Best Selling prequel novel, A Dragon among the Eagles. It is a FREE DOWNLOAD on Amazon, Apple iTunes/iBooks, and Kobo.

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part III – Combatants: The Tribes of the North

In the last post we looked at one of the sites that was right in the middle of the war zone beyond Hadrian’s Wall, a place that Rome used to good effect as it marched north over Britannia.

But who were the tribes north of Hadrian’s Wall that caused Rome such misery and bloodshed for over a hundred years? Who was Rome fighting?

In Part III of The World of Warriors of Epona, we’re going to look at the various combatants in our story.

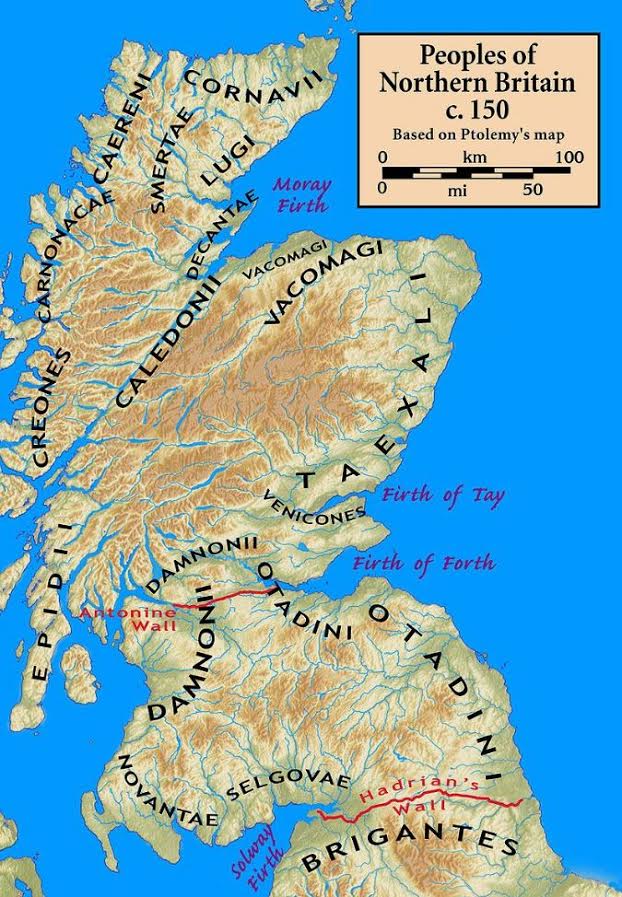

Tribes of Northern Britain according to Ptolemy (Wikimedia Commons)

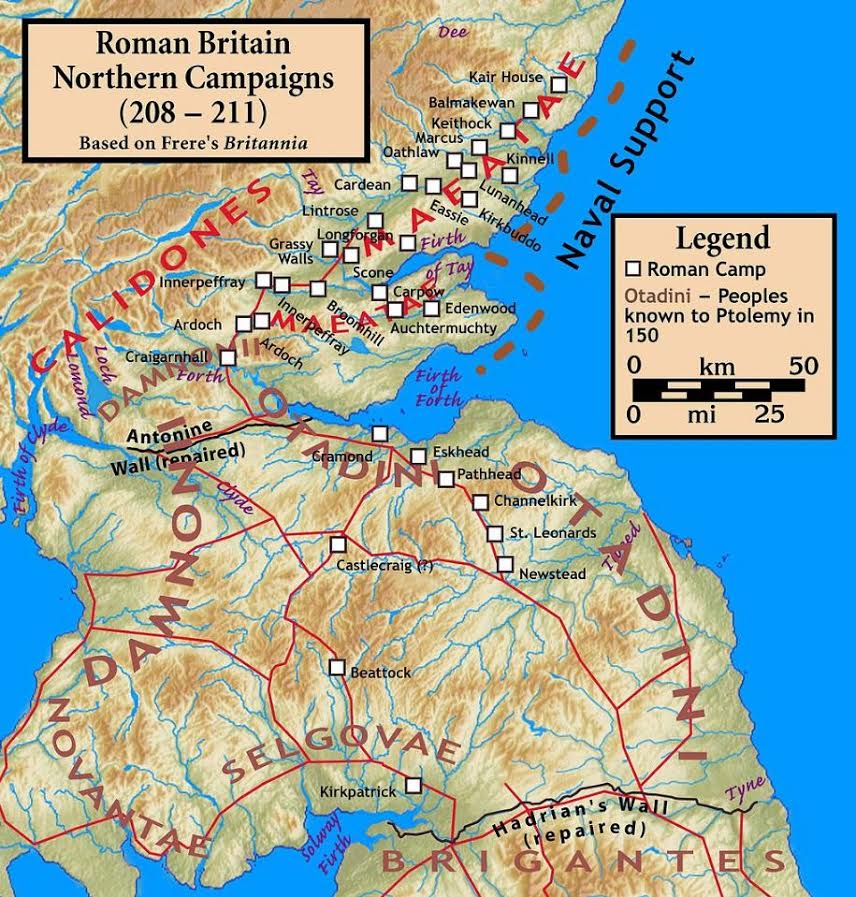

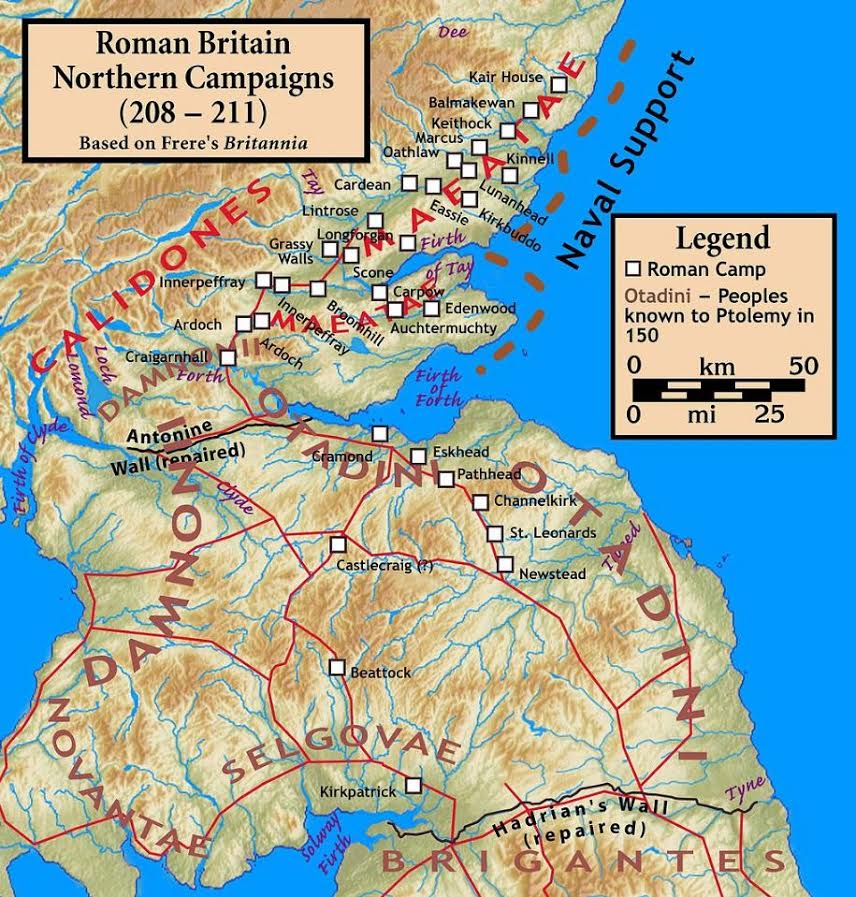

On a couple of occasions in the second century, the tribes north of the wall rebelled against Rome, and by the time Septimius Severus had finally defeated the Parthian Empire in the East, the time had come for Rome to deal once-and-for-all with the tribes of Caledonia.

This was no small venture.

Severus marched into Caledonia with at least six legions, his Praetorian Guard, plus numerous auxiliary units and cavalry ala, to deal with the rebellious tribes.

In this major offensive, the legions had to deal with bad weather, rough terrain, mountains, bogs, and river fords, as they attempted to take back strategic positions Rome had once held in previous campaigns.

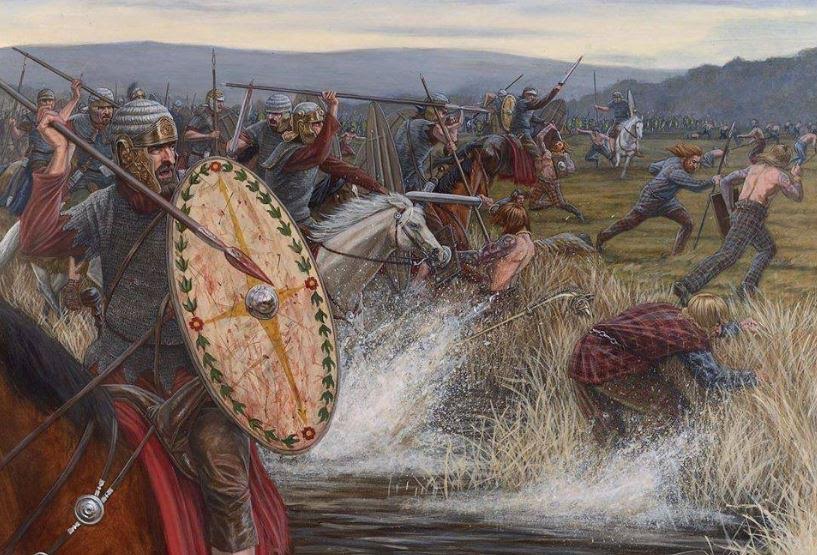

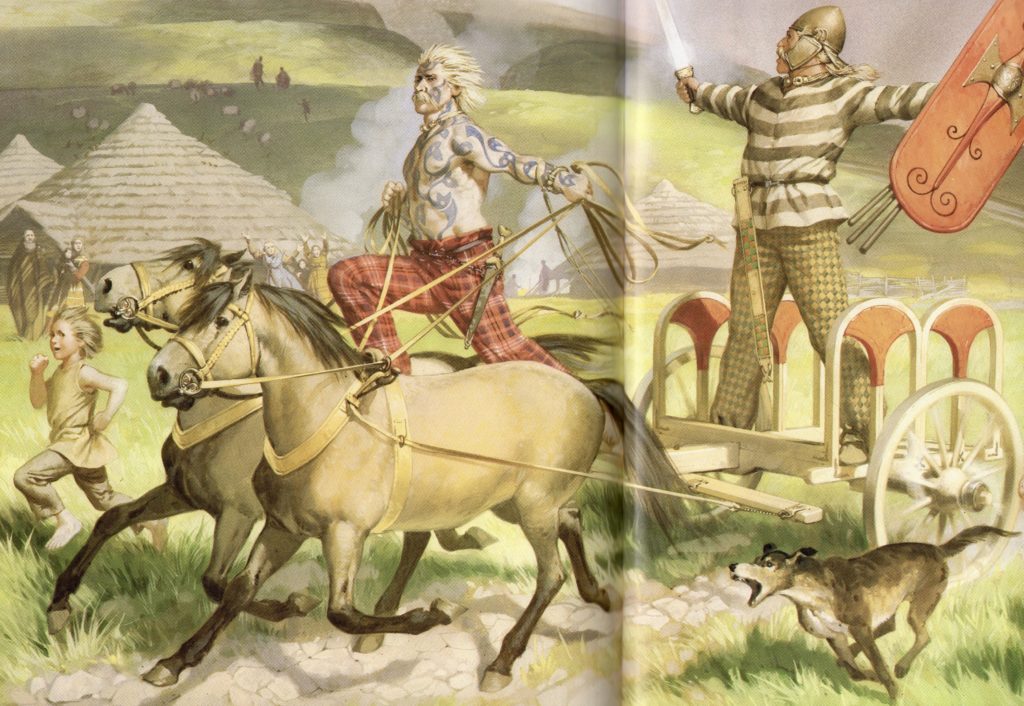

Rome’s foes were also cunning and highly skilled at their unique guerilla tactics, never meeting the legions in open, pitched battle. They were mostly infantry, but they also used war chariots. Their weapons often consisted of small round shields, short spears, and swords.

Their devices lured many a legionary to his doom too. Livestock would be used as bait to lure Roman troops into swamps or ambushes, and warriors would lie in wait submersed beneath the surface of water when the Romans were marching by.

It was all about hit and run and hacking away at the edges of Rome’s forces. And they were so good at it that, by the end of the campaign, the Romans are said to have lost around 50,000 men.

So who were these expert guerilla fighters who proved such a thorn in the side of Rome for almost the entirety of its time in Britannia and Caledonia?

Let’s find out.

Most of what we know about the names of the tribes at this time in Caledonia and northern Britannia comes down to us from Claudius Ptolemaeus, or Ptolemy as most know him.

Ptolemy was a Greco-Egyptian mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, and geographer who lived c. A.D.100-170. It is his work, known as Geographia, which compiles geographical coordinates and knowledge of the Roman Empire in the second century, and which mentions many of the tribes and locations we are dealing with during the Severan invasion of Caledonia.

Severan Campaigns in Caledonia (Wikimedia Commons)

Other sources for places during this period and in this region are the Ravenna Cosmography, which is an early eighth century list of place-names from Ireland to India, and the second century Antonine Itinerary. The latter was created under Antoninus Pius and likely finalized under Caracalla at the beginning of the third century. The portion of the itinerary known as Iter Britanniarum was a list of Roman place names and roads in Britain.

Rome was anything but invincible in this fight, so we need to look first at those who fought alongside the legions in Caledonia.

One of Rome’s allies in this fight were the Votadini, and they play a large role in Warriors of Epona.

This tribe of Celtic Britons held the territory of what is now south-east Scotland and north-east England, and they had been Roman allies for generations by the time of the Severan invasion, and may well have been one of the key Romano-British fighting forces.

The Votadini came under Roman alliance in the mid-second century, and proved to be a great stabilizing entity between the Antonine and Hadrianic walls, mainly the region we know today as the Scottish Borders.

Dunpedyrlaw (Trapain Law) – Capital of the Votadini

Their capital, named ‘Curia’ by Ptolemy, was called Dunpendyrlaw, which meant the ‘fort of the spear shafts’. Today, the massive hill fort at this place is known as Traprain Law. This place was occupied by the Votadini and their descendants until about A.D. 400 when the capital was moved to Din Eidyn, that is, Castle Rock in Edinburgh.

One of the most magnificent finds from the Votadini capital of Dunpendyrlaw is a hoard of Roman silver plates, cups and more. Some believe this was given to the Votadini in thanks for service to Rome, others that it was a bribe to keep them in check and fulfilling their role as allies.

Trapain Law Treasure

The Votadini’s descendants were none other than the Gododdin, those Britons who made an heroic last stand at the battle of Catraeth around A.D. 600 when the Saxons were poised to overrun the island. This final battle is chronicled in the poem, Y Gododdin by Aneirin.

The poem was certainly an inspiration for me when I was writing about the Votadini in this book. It seems quite romantic in a sense, the Votadini, loyal Rome, standing against the enemy tribes after Rome pulled back from Antonine Wall.

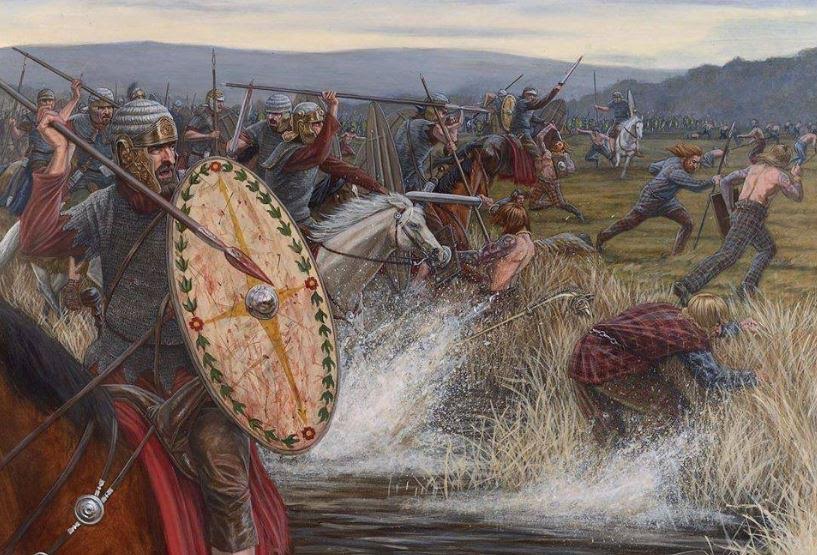

Artist impression of Roman cavalry ala engaging Caledonians

The other allies in this fight with Rome, although perhaps a little more reluctant, was a tribe known as the Venicones. Their lands covered what is basically modern Fife, in eastern Scotland, and where, funnily enough, my alma mater, St. Andrews University, is located.

The Venicones are known to us from Ptolemy who mentions a town by the name of ‘Orrea’ which many have come to identify as the Roman settlement of Horea Classis. This is believed to be the site of the Severan legionary base at Carpow, along the Tay estuary, and it is from here that the emperor likely oversaw the Caledonian campaign, when not in the northern capital of Eburacum (York).

The Venicones were in a tough position. On the one hand, they were neighbours with Rome’s enemies, the Caledonii to the West, and the Taexali to the North.

Crop marks showing outline of Roman Principia at Carpow

They chose to side with Rome in the fight, but one wonders how much of a choice that was? As it turned out, the legionary base and ports at Horea Classis (Carpow) and the forts of the Gask Ridge frontier (the topic of our next post), were all in the lands of the Venicones.

What must the Venicones have been thinking when they agreed, or were forced, to become a Roman client state?

I wouldn’t have wanted to be the one throwing those dice!

Ordnance Survey map extract (Gask ridge and Venicones lands)

Now we come to Rome’s adversaries in the Caledonian campaign.

Even though we have some hints from Ptolemy and the other sources, it is difficult to be exact in naming the tribes that Rome was fighting on this far northern frontier. Many Roman writers, including Cassius Dio, use the name ‘Caledonians’ for all the tribes rebelling against the Empire.

In writing Warriors of Epona, I had to pick and choose which tribes I would write about, and which to leave out.

There are three peoples in particular who may well have joined forces with larger groups but which I decided to leave out of the story specifically.

The first are the Novantae. These were a people of the second century who lived in modern Galloway and Carrick in south-western Scotland. The Saxon historian, Bede, refers to the Novantae as Picts in his history, but it is believed that they were a Brythonic people.

Another group I decided to leave out of the story were the Damnonii. These were Celtic Britons located in Strathclyde in southern Scotland. They are only mentioned by Ptolemy and there really is not enough information on them and their activities.

The third group I decided to leave out was the Maeatae. This group was larger, and believed by some to be a union of smaller tribes whose lands lay somewhere along the Antonine Wall, westward from Stirling. The little that I read about them indicates that they likely joined forces with the Caledonii in the rebellion of A.D. 210.

British warriors (illustrated by Angus McBride)

In Warriors of Epona, the Romans have to deal with two main adversaries in the Caledonian campaign – the Selgovae, and the Caledonii.

At the beginning of the book, Lucius Metellus Anguis and his Sarmatian cavalry ala are engaging the Selgovae in the lands around Trimontium, north of the wall.

The fighting has been brutal and the leader of the Selgovae ruthless in his campaign against Rome.

Who were the Selgovae?

They were a large tribe of Britons mentioned by Ptolemy in the late second century. Their territory covered south-west Scotland and what is Dumfriesshire today.

It is believed that they were related to the Brigantes, Rome’s old enemies south of Hadrian’s Wall.

The Selgovae, like many other British tribes, used chariots in warfare. They also lived in stone huts and had many hill forts across their lands. Their warlike demeanour and the strength of their fortresses made them an obvious target for Rome during successive campaigns. Like the Brigantes, the Selgovae were more troublesome than other tribes.

Aerial view of Eildon Hill North – Capital of the Selgovae

In a previous post, we have already discussed the legionary fortress at Trimontium, the place Lucius uses as a base in his fight against the Selgovae. But before Rome occupied the site, Eildon Hill North, one of Trimontium’s three peaks, was the main tribal centre of the Selgovae.

Writing about this group of warriors, making a last stand against Rome at the beginning of the story, was thrilling and bitter-sweet. They were a once-proud people, but, like many who stood against Rome, they had to face the harsh realities of the Empire.

The main opponents of Rome during the Caledonian campaigns of Septimius Severus, and in Warriors of Epona, were the Caledonii.

These were the indigenous people of what is now Scotland.

They were originally considered to be another group of Britons, but now it is more widely believed that they were the people who later came to be known as the Picts.

Pictish stone at the Meigle Museum in Strathmore, Scotland

The Caledonii may also have been a federation of many tribes in Scotland, as well as remnant forces fleeing north after being defeated by Rome in the South.

One thing is certain – Rome was a definite threat to all the northern tribes, and the scene was set for a brutal fight, with the Caledonii leading the charge.

The Caledonii were certainly a hearty people who lived in a very rugged world that included the Scottish Highlands. As the first century historian, Tacitus, points out, they had red hair and long limbs. Much later than Tacitus, Cassius Dio, our main source for the period, added a bit more colour to the picture of the Caledonii, saying that they:

…inhabit wild and waterless mountains and desolate and swampy plains, and possess neither walls, cities, nor tilled fields, but live on their flocks, wild game, and certain fruits; for they do not touch the fish which are there found in immense and inexhaustible quantities. They dwell in tents, naked and unshod, possess their women in common, and in common rear all the offspring. Their form of rule is democratic for the most part, and they are very fond of plundering; consequently they choose their boldest men as rulers. The go into battle in chariots, and have small, swift horses; there are also foot-soldiers, very swift running and very firm in standing their ground. For arms they have a shield and a short spear, with a bronze apple attached to the end of the spear-shaft, so that when it is shaken it may clash and terrify the enemy; and they also have daggers. They can endure hunger and cold and any kind of hardship; for they plunge into the swamps and exist there for many days with only their heads above water, and in the forests they support themselves upon bark and root…

(Cassius Dio, Roman History 12,1)

One must always take ancient writers’ descriptions with a grain of salt, of course, but if even a part of this description of the Caledonii is true, then the Romans must have felt like they were fighting ghosts as they marched into Caledonia.

Artist impression of a Caledonian warrior

The Severan campaign was certainly not the first time Rome engaged the Caledonians. There were other campaigns which we shall look at in a later post in this blog series.

Prior to Severus’ invasion, the Caledonians rebelled in A.D. 180 when they travelled south and breached Hadrian’s Wall. And then in A.D. 197, the Caledonii, Brigantes, and Maeatae led another attack on the frontier.

At the time of these rebellions, Severus was campaigning against the Parthians in the East.

By the time A.D. 209 rolled around, Rome’s legions were set for the biggest offensive yet into Caledonia.

Once again, Cassius Dio gives us an account:

Severus, accordingly, desiring to subjugate the whole of it, invaded Caledonia. But as he advanced through the country he experienced countless hardships in cutting down forests, levelling the heights, filling up swamps, and bridging rivers; but he fought no battle and beheld no enemy in battle array. The enemy purposely put sheep and cattle in front of the soldiers for them to seize in order that they might be lured on still further until they were worn out; for in fact the water caused great suffering to the Romans, and when they became scattered, they would be attacked. Then, unable to walk, they would be slain by their own men, in order to avoid capture, so that a full fifty thousand died.

(Cassius Dio, Roman History 14,1)

Caledonia: The Scottish Highlands

Some believe that Septimius Severus actually wanted to settle the North and that there were plans for a city near the Tay estuary, but others stand firm in the belief that the goal of the Severan campaign was none other than the mass genocide of the Caledonii who had proved supremely troublesome to Rome for a long time.

Whatever the reasons for Severus’ invasion of Caledonia, one thing is certain – with their guerilla tactics, rough terrain, and sheer determination to keep Rome out of their lands, the Caledonii and their allies gave the men of the legions a fight for their lives.

We mustn’t think, however, that Rome was adrift and defenseless in Caledonia. On the contrary, the Empire dug in for a fight and, as part of Lucius’ mission in Warriors of Epona, they took back an old frontier to hem the Caledonians in on their highlands.

This battle line, this frontier, will be the subject of Part IV of The World of Warriors of Epona.

Thank you for reading.

The World of Rosslyn Chapel

I can’t believe the holidays are upon us already. Where did autumn go to? It seems that the festive time of year always manages to creep up on us.

And that’s a good thing! It certainly is time for a bit of a break, some good cheer, and a few helpings of my homemade wassail.

I hope you enjoyed the wonderful posts from my fellow authors during the Holiday Historical Fiction Blowout event from December 1-8th. It was a very busy eight days, but we had a great time, met some new readers, and picked up some great books!

I hope many of you were able to take advantage of the fantastic .99 cent deals.

Time for a new blog post.

During this time of year, with the run-up to Christmas, talk of yule logs, wassail (drink and carols), I always tend to gravitate toward my Medieval interests.

Summer makes me think of ancient Greece and Rome, but the time of the Winter Solstice sets me firmly in the Middle Ages. Perhaps it’s the songs I imagine being sung in soaring cathedrals, or the glow of bees’ wax candles among fresh strands of cedar and pine. I have a bit more time at home, and it becomes my castle, a place where I can sit, read one of my antiquarian books of Arthurian tales, and think back on the year with gratitude.

After digging up the Christmas ornaments last weekend, I was going through one of many boxes of old photos that I have from my studies and travels, and came upon a packet of prints from a visit to a truly amazing place – Rosslyn Chapel.

Having lived in St. Andrews, Scotland for a couple of years, I had the opportunity to visit new and interesting sites all of the time, from Melrose and the Roman fort at Trimontium in the Scottish borders, to Inverness and Eilean Donan castle, and everything in between. It was something new every weekend. You can visit prehistoric sites, Pictish hill forts and Roman remains, of which there are many.

The great thing about living in Britain is that there are more medieval sites to visit than you can possible see in a lifetime.

One of the most interesting sites that I did visit during my time in St. Andrews was Rosslyn Chapel.

I was fortunate enough to have done this in the pre-Da Vinci Code days of publishing after which, I am certain, hordes of eager tourists turned the quiet chapel into a virtual marketplace of symbology. I’m not trashing that as I’m sure the major influx of funds helped Rosslyn Chapel to complete the restoration which finished in 2013. When I visited the chapel, there was scaffold everywhere, along with piles of stone that were to be used in the work.

But oh, what a place! And what a treat for me and my three friends to have it all to ourselves at the time.

Rosslyn Chapel lies just south of Edinburgh and has been known as many things throughout its history – the Chapel of the Grail, a key to the secrets and treasures of the Templar Knights, the survivors of which were absorbed, some say, into the Masonic order. Certainly, many authors and historians have contributed to theories that go beyond the boundaries of conventional academia. And why not? It makes for fascinating fiction as well as some perfectly viable historical theories. A few book mentions later on.

Rosslyn Chapel was founded in 1446 (a few years after the founding of St. Andrews University in 1410, my alma mater) by Sir William St. Clair, the last St. Clair Prince of Orkney, who was buried in the chapel. It took some forty years to build what remains today and even that was not what was intended, for the original plan called for a larger structure. Evidence of this was found in an early excavation when the archaeologists discovered foundation walls that went well beyond the existing walls. Not everyone perceived Rosslyn as a sanctuary, a work of art, or marvel of mysticism. Many, especially protestants, labelled Rosslyn as a house of idolatry, no doubt disconcerted by the images staring at them from every corner of the intensely ornate chapel.

I will not go into the long history of Rosslyn Chapel here as this is more of a short pictorial tease. However, this place was not awarded the respect that was due to such a work of art. In 1650, during the Civil War, when Oliver Cromwell’s troops were besieging St. Clair Castle (only about 100 meters away), the English horses were stabled in the chapel. In 1688, pro-Protestant villagers from Roslin entered and damaged the chapel because it was “Popish and idolatrous”.

It was abandoned until 1736 when James St. Clair repaired the windows, roof and floors. If you have read a great deal about Rosslyn, the Templars and/or Masons, you will know that the name of St. Clair (or Sinclair) figures prominently.

In April of 1862, Rosslyn Chapel was rededicated as a place for worship and has undergone various stages of repair over the years, including when I visited in 2000.

It is, unfortunately, easy to get taken up with picture taking in such a place. I know that at first, I certainly did, but once I ran out of film (yes, before digital was common!) I was able to sit quietly in that place and admire it for a while. I remember it being very quiet, and there certainly was a feeling of constantly being watched (and not by CCTV cameras!). No, there was definitely a feeling to the place, unlike any other.

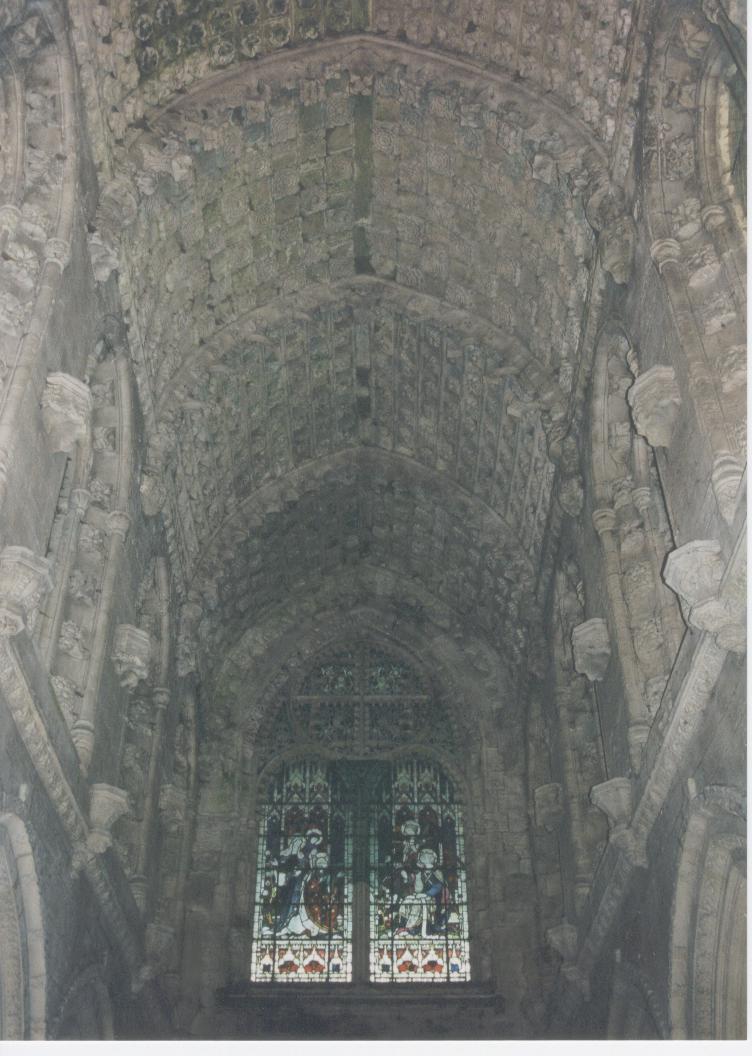

Yes, you do have some of the usual religious iconography and stained glass, but there is more of the unusual and mysterious. Questions certainly abound. For instance, the appearance of American vegetation such as aloe or Indian corn! There is a plethora of mythical creatures, dragons especially, of unusual angels such as the one playing the bag pipes, or another carrying the heart of Robert the Bruce (could it be the Black Douglas who was to take the Bruce’s heart to Jerusalem?).

One of the most famous works in the chapel is the Apprentice Pillar. This twisted pillar, based with eight coiled dragons, is a true masterpiece and the story goes that when the master mason was away, his apprentice continued to work and created something that far surpassed that of the master. The master mason was so enraged with jealousy that he killed the apprentice with his mallet.

I think however, that the most striking thing for me was the barrel-vaulted ceiling of the chapel. At one point, you look up and there above is an intricate pattern of alternating daisies, lilies, flowers, Roses and stars.

Numerous books have been written about this place, countless pictures published on-line, but there is no substitute for actually visiting it and interacting with it.

Rosslyn has quite a story to tell, no matter what your perspective. You can gaze at it for hours and not see it all.

Here are a few recommended reads that touch on Rosslyn, but also on the Templars and Masons. If fiction is your thing, check out Jack Whyte’s Templar Trilogy in which the St. Clairs make an appearance. Oh, and why not check out Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code – it may not be literary fiction, but it is highy entertaining and has caused millions of people to pick up a book and read who might not otherwise have done so. Besides, he fictionalizes some quite interesting theories put forward by Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh as well as other alternative historian/detectives.

A couple of non-fiction recommendations that I have are Rosslyn, Guardian of the Secrets of the Holy Grail by Tim Wallace-Murphy and Marilyn Hopkins and secondly, The Sword and the Grail by Andrew Sinclair. The latter is a very interesting exploration into the Templars and the possibility that they travelled to North America more than ninety years before Columbus’s journey of discovery. I know, it sounds mad, but it’s truly fascinating and besides, the Vikings discovered Newfoundland some five hundred or so years before Columbus! For you alternative history buffs out there, you’ll already have made the link to the carvings of Indian corn and aloe on the walls or Rosslyn Chapel.

Well, that’s all for now. I hope you’ve enjoyed this post. Be sure to check out the Rosslyn Chapel website for more information.

As ever, thank you for reading.

Also, do check out this 4-part BBC documentary on Rosslyn Chapel hosted by art historian, Helen Rosslyn – yes, the chapel has been in her family for hundreds of years!