In the last post we looked at one of the sites that was right in the middle of the war zone beyond Hadrian’s Wall, a place that Rome used to good effect as it marched north over Britannia.

But who were the tribes north of Hadrian’s Wall that caused Rome such misery and bloodshed for over a hundred years? Who was Rome fighting?

In Part III of The World of Warriors of Epona, we’re going to look at the various combatants in our story.

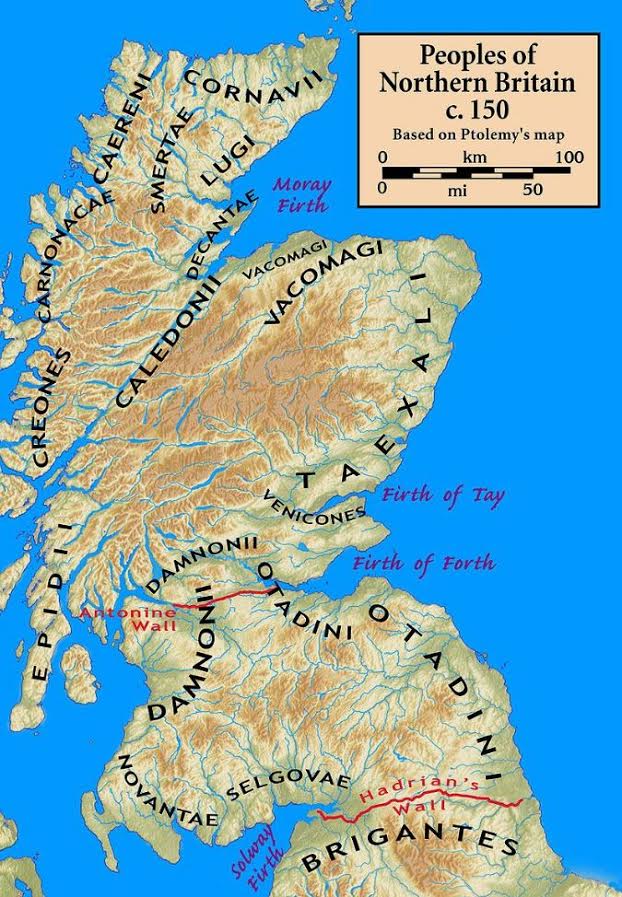

Tribes of Northern Britain according to Ptolemy (Wikimedia Commons)

On a couple of occasions in the second century, the tribes north of the wall rebelled against Rome, and by the time Septimius Severus had finally defeated the Parthian Empire in the East, the time had come for Rome to deal once-and-for-all with the tribes of Caledonia.

This was no small venture.

Severus marched into Caledonia with at least six legions, his Praetorian Guard, plus numerous auxiliary units and cavalry ala, to deal with the rebellious tribes.

In this major offensive, the legions had to deal with bad weather, rough terrain, mountains, bogs, and river fords, as they attempted to take back strategic positions Rome had once held in previous campaigns.

Rome’s foes were also cunning and highly skilled at their unique guerilla tactics, never meeting the legions in open, pitched battle. They were mostly infantry, but they also used war chariots. Their weapons often consisted of small round shields, short spears, and swords.

Their devices lured many a legionary to his doom too. Livestock would be used as bait to lure Roman troops into swamps or ambushes, and warriors would lie in wait submersed beneath the surface of water when the Romans were marching by.

It was all about hit and run and hacking away at the edges of Rome’s forces. And they were so good at it that, by the end of the campaign, the Romans are said to have lost around 50,000 men.

So who were these expert guerilla fighters who proved such a thorn in the side of Rome for almost the entirety of its time in Britannia and Caledonia?

Let’s find out.

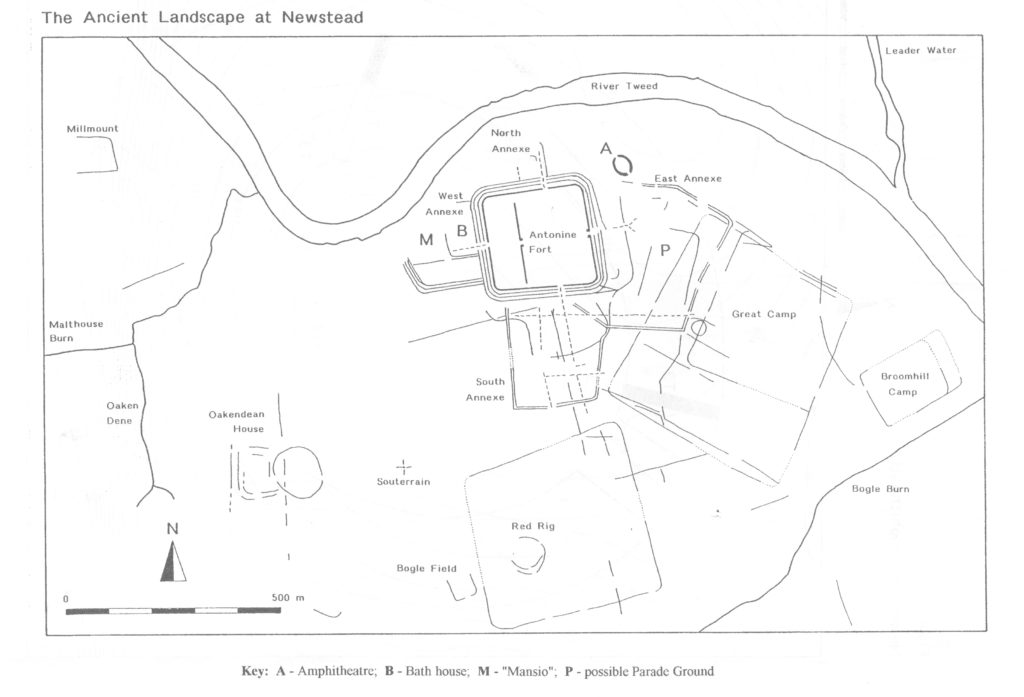

Most of what we know about the names of the tribes at this time in Caledonia and northern Britannia comes down to us from Claudius Ptolemaeus, or Ptolemy as most know him.

Ptolemy was a Greco-Egyptian mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, and geographer who lived c. A.D.100-170. It is his work, known as Geographia, which compiles geographical coordinates and knowledge of the Roman Empire in the second century, and which mentions many of the tribes and locations we are dealing with during the Severan invasion of Caledonia.

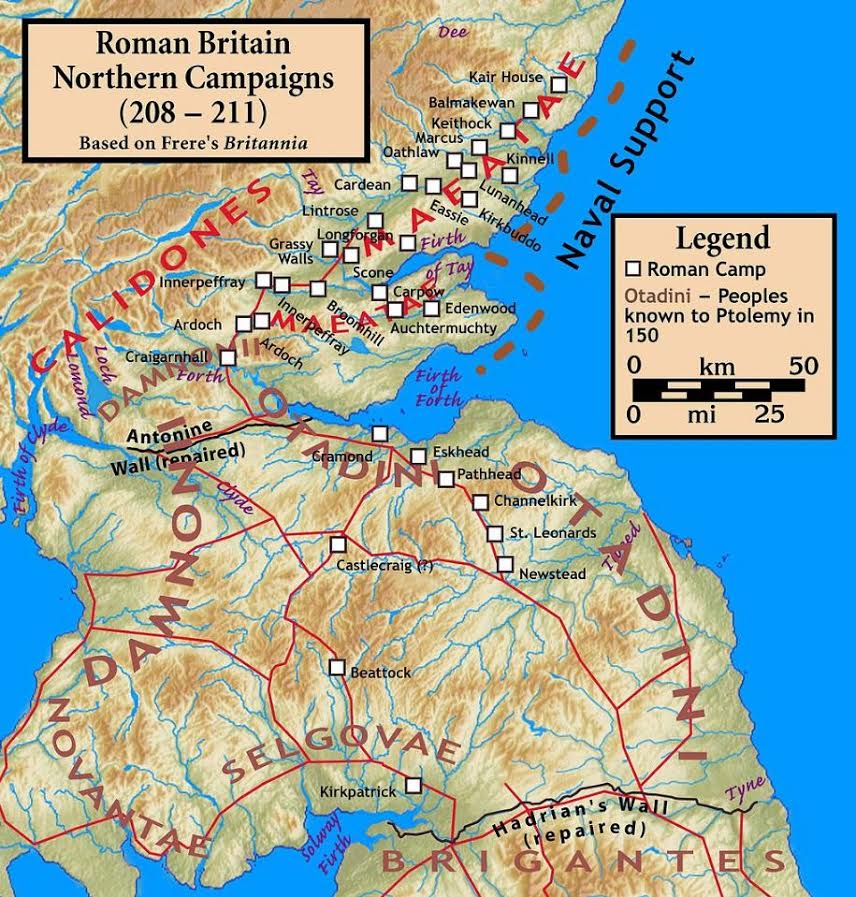

Severan Campaigns in Caledonia (Wikimedia Commons)

Other sources for places during this period and in this region are the Ravenna Cosmography, which is an early eighth century list of place-names from Ireland to India, and the second century Antonine Itinerary. The latter was created under Antoninus Pius and likely finalized under Caracalla at the beginning of the third century. The portion of the itinerary known as Iter Britanniarum was a list of Roman place names and roads in Britain.

Rome was anything but invincible in this fight, so we need to look first at those who fought alongside the legions in Caledonia.

One of Rome’s allies in this fight were the Votadini, and they play a large role in Warriors of Epona.

This tribe of Celtic Britons held the territory of what is now south-east Scotland and north-east England, and they had been Roman allies for generations by the time of the Severan invasion, and may well have been one of the key Romano-British fighting forces.

The Votadini came under Roman alliance in the mid-second century, and proved to be a great stabilizing entity between the Antonine and Hadrianic walls, mainly the region we know today as the Scottish Borders.

Dunpedyrlaw (Trapain Law) – Capital of the Votadini

Their capital, named ‘Curia’ by Ptolemy, was called Dunpendyrlaw, which meant the ‘fort of the spear shafts’. Today, the massive hill fort at this place is known as Traprain Law. This place was occupied by the Votadini and their descendants until about A.D. 400 when the capital was moved to Din Eidyn, that is, Castle Rock in Edinburgh.

One of the most magnificent finds from the Votadini capital of Dunpendyrlaw is a hoard of Roman silver plates, cups and more. Some believe this was given to the Votadini in thanks for service to Rome, others that it was a bribe to keep them in check and fulfilling their role as allies.

Trapain Law Treasure

The Votadini’s descendants were none other than the Gododdin, those Britons who made an heroic last stand at the battle of Catraeth around A.D. 600 when the Saxons were poised to overrun the island. This final battle is chronicled in the poem, Y Gododdin by Aneirin.

The poem was certainly an inspiration for me when I was writing about the Votadini in this book. It seems quite romantic in a sense, the Votadini, loyal Rome, standing against the enemy tribes after Rome pulled back from Antonine Wall.

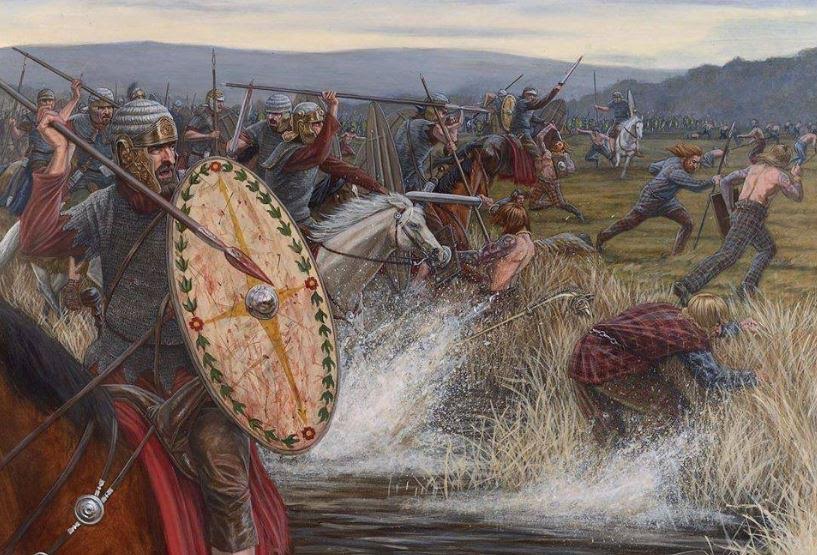

Artist impression of Roman cavalry ala engaging Caledonians

The other allies in this fight with Rome, although perhaps a little more reluctant, was a tribe known as the Venicones. Their lands covered what is basically modern Fife, in eastern Scotland, and where, funnily enough, my alma mater, St. Andrews University, is located.

The Venicones are known to us from Ptolemy who mentions a town by the name of ‘Orrea’ which many have come to identify as the Roman settlement of Horea Classis. This is believed to be the site of the Severan legionary base at Carpow, along the Tay estuary, and it is from here that the emperor likely oversaw the Caledonian campaign, when not in the northern capital of Eburacum (York).

The Venicones were in a tough position. On the one hand, they were neighbours with Rome’s enemies, the Caledonii to the West, and the Taexali to the North.

Crop marks showing outline of Roman Principia at Carpow

They chose to side with Rome in the fight, but one wonders how much of a choice that was? As it turned out, the legionary base and ports at Horea Classis (Carpow) and the forts of the Gask Ridge frontier (the topic of our next post), were all in the lands of the Venicones.

What must the Venicones have been thinking when they agreed, or were forced, to become a Roman client state?

I wouldn’t have wanted to be the one throwing those dice!

Ordnance Survey map extract (Gask ridge and Venicones lands)

Now we come to Rome’s adversaries in the Caledonian campaign.

Even though we have some hints from Ptolemy and the other sources, it is difficult to be exact in naming the tribes that Rome was fighting on this far northern frontier. Many Roman writers, including Cassius Dio, use the name ‘Caledonians’ for all the tribes rebelling against the Empire.

In writing Warriors of Epona, I had to pick and choose which tribes I would write about, and which to leave out.

There are three peoples in particular who may well have joined forces with larger groups but which I decided to leave out of the story specifically.

The first are the Novantae. These were a people of the second century who lived in modern Galloway and Carrick in south-western Scotland. The Saxon historian, Bede, refers to the Novantae as Picts in his history, but it is believed that they were a Brythonic people.

Another group I decided to leave out of the story were the Damnonii. These were Celtic Britons located in Strathclyde in southern Scotland. They are only mentioned by Ptolemy and there really is not enough information on them and their activities.

The third group I decided to leave out was the Maeatae. This group was larger, and believed by some to be a union of smaller tribes whose lands lay somewhere along the Antonine Wall, westward from Stirling. The little that I read about them indicates that they likely joined forces with the Caledonii in the rebellion of A.D. 210.

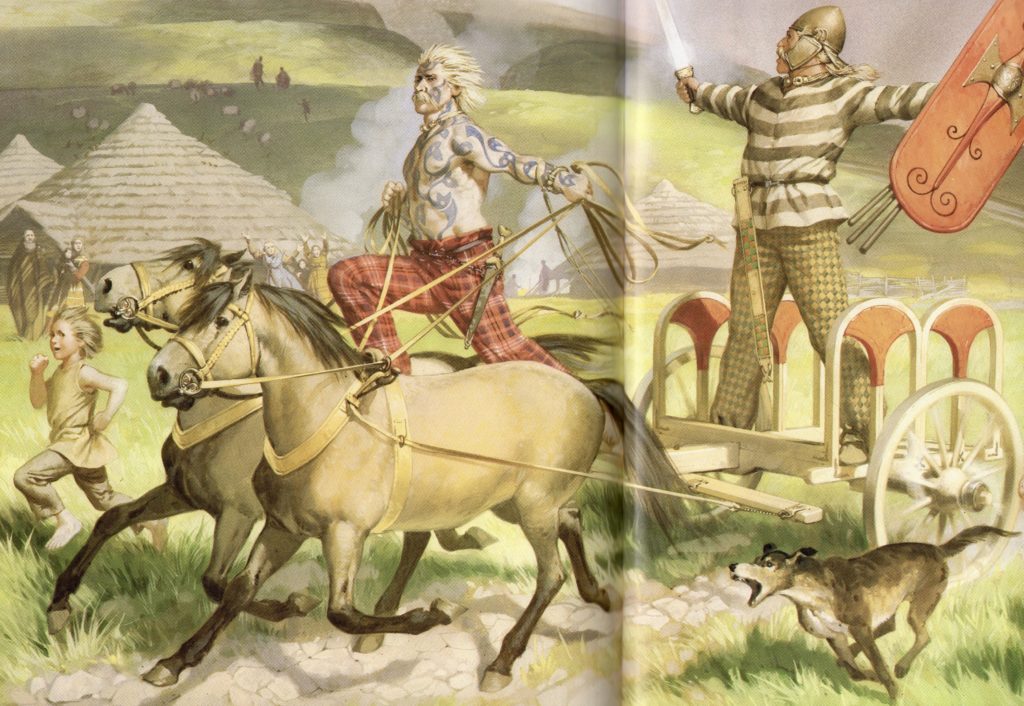

British warriors (illustrated by Angus McBride)

In Warriors of Epona, the Romans have to deal with two main adversaries in the Caledonian campaign – the Selgovae, and the Caledonii.

At the beginning of the book, Lucius Metellus Anguis and his Sarmatian cavalry ala are engaging the Selgovae in the lands around Trimontium, north of the wall.

The fighting has been brutal and the leader of the Selgovae ruthless in his campaign against Rome.

Who were the Selgovae?

They were a large tribe of Britons mentioned by Ptolemy in the late second century. Their territory covered south-west Scotland and what is Dumfriesshire today.

It is believed that they were related to the Brigantes, Rome’s old enemies south of Hadrian’s Wall.

The Selgovae, like many other British tribes, used chariots in warfare. They also lived in stone huts and had many hill forts across their lands. Their warlike demeanour and the strength of their fortresses made them an obvious target for Rome during successive campaigns. Like the Brigantes, the Selgovae were more troublesome than other tribes.

Aerial view of Eildon Hill North – Capital of the Selgovae

In a previous post, we have already discussed the legionary fortress at Trimontium, the place Lucius uses as a base in his fight against the Selgovae. But before Rome occupied the site, Eildon Hill North, one of Trimontium’s three peaks, was the main tribal centre of the Selgovae.

Writing about this group of warriors, making a last stand against Rome at the beginning of the story, was thrilling and bitter-sweet. They were a once-proud people, but, like many who stood against Rome, they had to face the harsh realities of the Empire.

The main opponents of Rome during the Caledonian campaigns of Septimius Severus, and in Warriors of Epona, were the Caledonii.

These were the indigenous people of what is now Scotland.

They were originally considered to be another group of Britons, but now it is more widely believed that they were the people who later came to be known as the Picts.

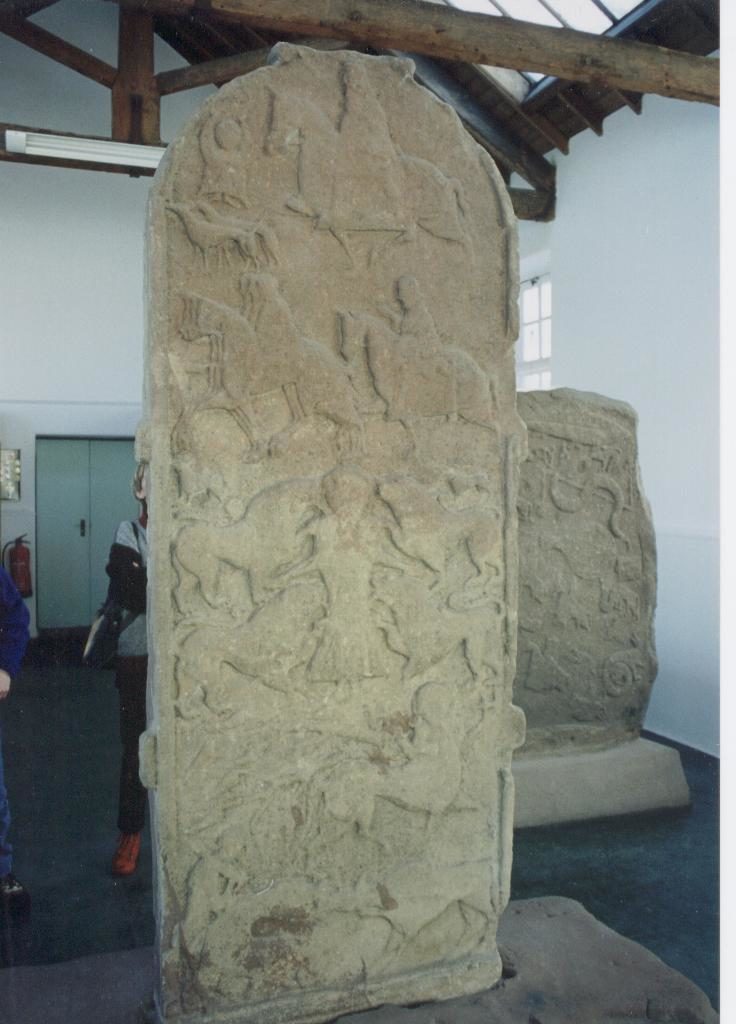

Pictish stone at the Meigle Museum in Strathmore, Scotland

The Caledonii may also have been a federation of many tribes in Scotland, as well as remnant forces fleeing north after being defeated by Rome in the South.

One thing is certain – Rome was a definite threat to all the northern tribes, and the scene was set for a brutal fight, with the Caledonii leading the charge.

The Caledonii were certainly a hearty people who lived in a very rugged world that included the Scottish Highlands. As the first century historian, Tacitus, points out, they had red hair and long limbs. Much later than Tacitus, Cassius Dio, our main source for the period, added a bit more colour to the picture of the Caledonii, saying that they:

…inhabit wild and waterless mountains and desolate and swampy plains, and possess neither walls, cities, nor tilled fields, but live on their flocks, wild game, and certain fruits; for they do not touch the fish which are there found in immense and inexhaustible quantities. They dwell in tents, naked and unshod, possess their women in common, and in common rear all the offspring. Their form of rule is democratic for the most part, and they are very fond of plundering; consequently they choose their boldest men as rulers. The go into battle in chariots, and have small, swift horses; there are also foot-soldiers, very swift running and very firm in standing their ground. For arms they have a shield and a short spear, with a bronze apple attached to the end of the spear-shaft, so that when it is shaken it may clash and terrify the enemy; and they also have daggers. They can endure hunger and cold and any kind of hardship; for they plunge into the swamps and exist there for many days with only their heads above water, and in the forests they support themselves upon bark and root…

(Cassius Dio, Roman History 12,1)

One must always take ancient writers’ descriptions with a grain of salt, of course, but if even a part of this description of the Caledonii is true, then the Romans must have felt like they were fighting ghosts as they marched into Caledonia.

Artist impression of a Caledonian warrior

The Severan campaign was certainly not the first time Rome engaged the Caledonians. There were other campaigns which we shall look at in a later post in this blog series.

Prior to Severus’ invasion, the Caledonians rebelled in A.D. 180 when they travelled south and breached Hadrian’s Wall. And then in A.D. 197, the Caledonii, Brigantes, and Maeatae led another attack on the frontier.

At the time of these rebellions, Severus was campaigning against the Parthians in the East.

By the time A.D. 209 rolled around, Rome’s legions were set for the biggest offensive yet into Caledonia.

Once again, Cassius Dio gives us an account:

Severus, accordingly, desiring to subjugate the whole of it, invaded Caledonia. But as he advanced through the country he experienced countless hardships in cutting down forests, levelling the heights, filling up swamps, and bridging rivers; but he fought no battle and beheld no enemy in battle array. The enemy purposely put sheep and cattle in front of the soldiers for them to seize in order that they might be lured on still further until they were worn out; for in fact the water caused great suffering to the Romans, and when they became scattered, they would be attacked. Then, unable to walk, they would be slain by their own men, in order to avoid capture, so that a full fifty thousand died.

(Cassius Dio, Roman History 14,1)

Caledonia: The Scottish Highlands