Welcome back to The World of The Dragon: Genesis, the blog series in which we’re delving into the research behind our latest historical fantasy release, The Dragon: Genesis. If you haven’t downloaded your free copy of the book yet, you can do so HERE.

In Part III we looked at the division of the province of Dacia in the years after Trajan’s conquest. If you missed that, you can read it HERE.

Today, in Part IV, we’re going to be taking a brief look at a class of soldiers among the veterans of ancient Rome and how they often provided a strong back-bone in the ranks of Rome’s legions. We’re going to be looking at the Evocati.

In truth, primary and secondary sources do not have a great deal to say about the Evocati of ancient Rome. And yet, they were important, highly-respected members of society across the Empire.

So, what exactly was an evocatus?

The basic definition is that an evocatus was a retired Roman soldier who returned to duty after his completed term of service.

Some of you might remember this scene from the HBO hit series, ROME, in which Lucius Vorenus decides to go back into the service as an evocatus:

https://youtu.be/g1PBt0NDv64

HBO’s ROME was a great series, but this scene seems more akin to the vigil kept by a newly-made knight during the Middle Ages. Truthfully, we don’t know how much, if any, ceremony was involved around becoming an evocatus. It may have been more of a clerical process, though religion was a big part of daily life.

What the scene above does, however, is portray the weight of the decision that re-enlisting might have had for a Roman who had already served for years in the legions.

From what we can gather, the Evocati gained more importance and respect during the Empire versus the Republic.

During the Roman Republic, the Evocati were ‘called-out’, which is where the meaning of the word comes from. This implies that they were compelled to return to service rather than given the choice. Calling out the Evocati might have been akin to instituting a draft in the Roman world.

During the Empire, however, veteran soldiers were invited to continue service as evocati, or they re-enlisted willingly.

There were two classes of evocati– the regular evocati of the legions, and the Evocati Augusti, the ‘Emperor’s Evocati’, who were former Praetorians who became evocati.

Before we go further, we should take a brief look at the veterans of ancient Rome.

Firstly, how long a man served depended on which military force he was a part of. The lengths of time shift slight back and forth over the centuries, but generally, a legionary soldier served for 20 years, a Praetorian guardsman served or 16 years, and an auxiliary trooper served for about 26 years.

These terms of service might seem short to us today, especially when some people spend up to 35 years in a career, but it is important to keep in mind that the average age of mortality in the ancient world was much younger than today.

Twenty years spent in the legions was a much greater portion of a man’s life than we might think.

For veterans, the type of discharge one received was important, as it also determined the type life one might have enjoyed afterward. The discharge types were missio causaria (discharge through injury or illness), missio ignominiosa (dishonourable discharge), and honesta missio (honourable discharge).

If one completed the full term of service, and received an honourable discharge, then life was often pretty good. Veterans had legal status in ancient Rome, and were protected by laws granting them certain rights and immunities. They could go on to be local decurions (a sort of city councilor), and they could form collegia.

Veterans received land grants too, and it is said that Emperor Augustus settled about 300,000 veterans in colonies across the empire.

Emperor Augustus

Upon being honourably discharged, veterans also received money, in addition to land. A legionary received 3000 denarii (later raised to 5000), and a Praetorian received 5000 denarii (later raised to 8250). Soldiers were also given back the savings they had been forced to put away during their time in the army. Under Hadrian, the land grants to veterans stopped, but they were still given fair financial recompense.

It seems that world leaders today could take their cue from the ancient Romans when it comes to taking care of veterans after their service is finished.

Veterans were leaders in coloniae across the Empire, and there was a peace and security present where veterans settled. This in turn attracted other civilians as the veterans also provided a skilled workforce locally. They were good for the economy too.

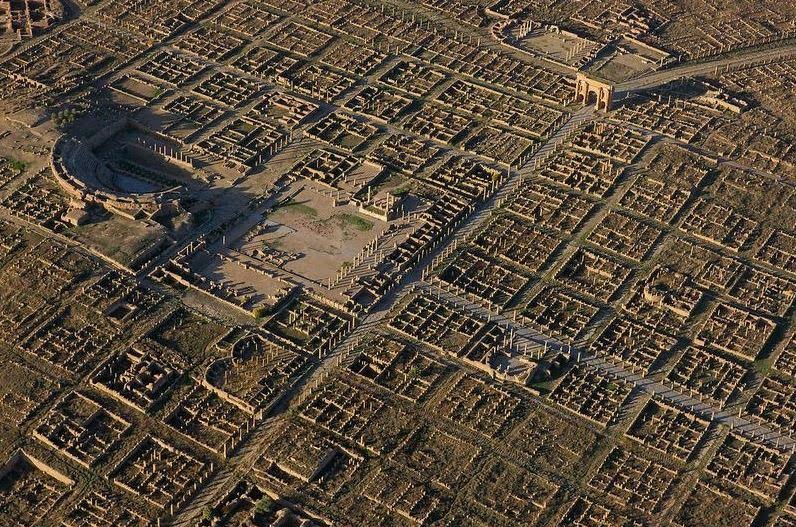

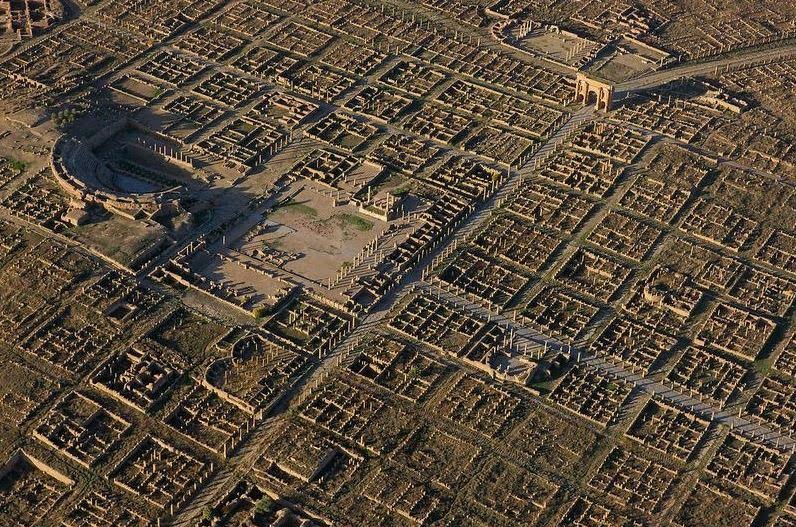

One example of a thriving veteran colonia on the edge of the Empire is Thamugadi, in Numidia, which was located a short distance from the legionary fortress of Lambaesis.

Aerial view of the colonia of Thamugadi, Numidia (North Africa), where veterans of the III Augustan Legion at Lambaesis were settled.

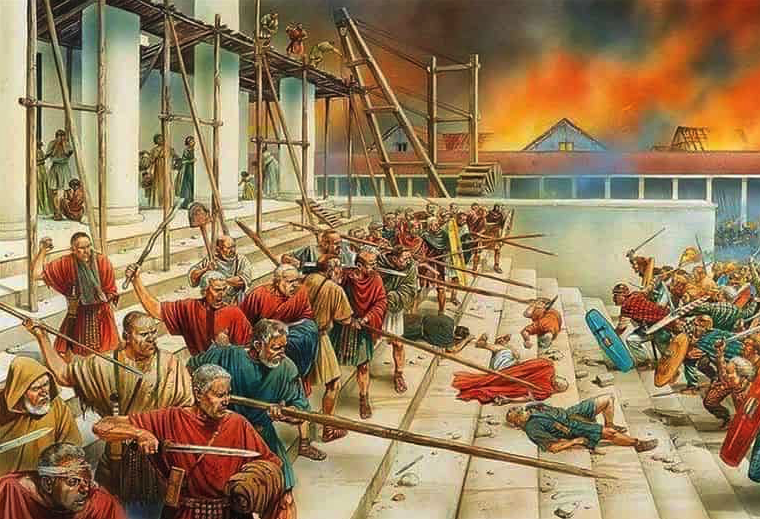

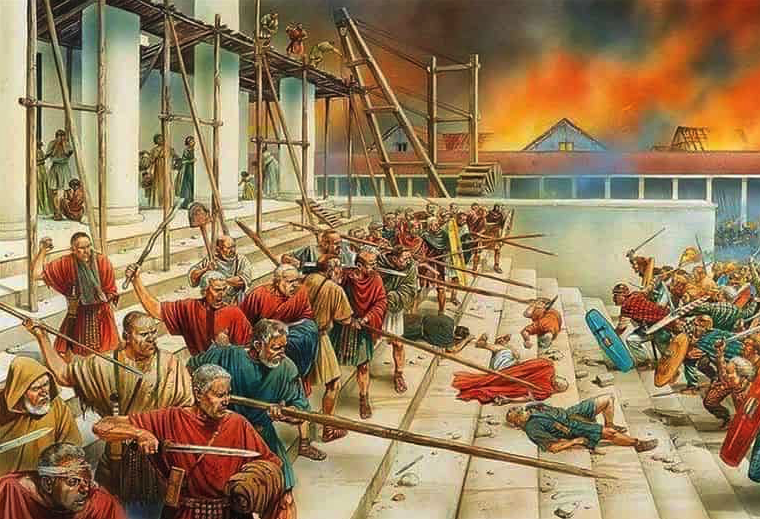

Not everyone was happy, however, with the presence of Roman veterans. Tacitus tells us of the tension between local Britons and their retired Roman conquerors:

And the humiliated Iceni feared still worse, now that they had been reduced to provincial status. So they rebelled. With them rose the Trinovantes and others. Servitude had not broken them, and they had secretly plotted together to become free again. They particularly hated the Roman ex-soldiers who had recently established a settlement at Camulodunum. The settlers drove the Trinovantes from their homes and land, and called them prisoners and slaves. The troops encouraged the settlers’ outrages, since their own way of behaving was the same – and they looked forward to similar license for themselves. (Tacitus, Annals XIV.33)

If most veterans who had been honourably discharged seemed to enjoy a good life (for them as Romans, that is), doing as they pleased on their granted lands, why might they have considered joining the ranks of the Evocati and going back to war?

Why were the Evocati even needed with so vast an empire?

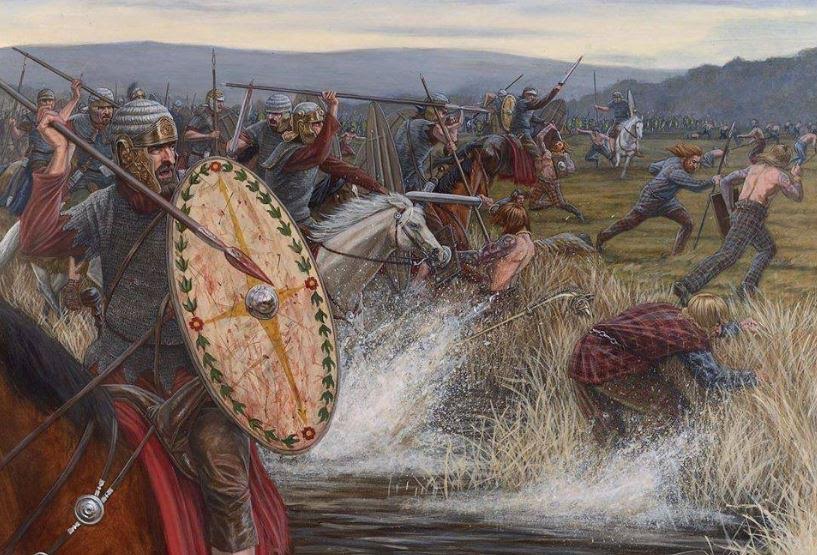

Well, the Evocati were a sort of ready, trained militia that could be called upon in times of emergency, such as during the Boudiccan revolt of A.D. 60 when Governor Paulinus Suetonius called upon 2500 evocati to join the fighting. As Tacitus tell us, “the old battle-experienced soldiers longed to hurl their javelins. So Suetonius confidently gave the signal for battle.”

Artist impression of veterans defending Camulodunum

Evocati reported directly to the governor of a Roman province, so, in times of emergency, they could be used to reinforce the garrison.

Other reasons men might join the Evocati were the need for money if they had fallen on hard times, or even the need for purpose in life after the army. Just as today, it may not have been easy for a career soldier to reintegrate into civilian society, and so many might have welcomed the opportunity to go back to the ranks.

Lastly, men could be requested to re-enter service by the consul or their former commander. This happened frequently during civil wars. At the battle of Pharsalus, Pompey used 2000 evocati against Caesar, and later, Octavian enlisted 3000 evocati when going up against Marcus Antonius. In A.D. 67, Mucianus, the governor of Syria, is said to have enlisted 13,000 evocati to move against Emperor Vitellius.

I cannot give the exact strength…for the Evocati. Augustus was the first to employ this corps when he re-enlisted those troops who had served under Julius Caesar to fight against Antony, and he kept them in service afterward. To this day, they constitute a special corps and carry ceremonial rods as centurions do.(Cassius Dio, The Roman History 24)

When Augustus made the Evocati a sort of official class, as hinted at by Cassius Dio, was it just so that they could fight in times of emergency, or did they have some other purpose? What incentives were there for a veteran who had already served for years in the army to return to service?

Praetorian officers

It seems that when a man became an evocatus, he had special privileges. The Evocati did not go back to digging ditches and manning the front lines in battle. They were too valuable an asset for that.

Apart from fighting when the need arose, the Evocati fulfilled various other roles. They became instructors of aquilifers and other standard bearers, and physical trainers for the regular troops. Many evocati returned to the ranks to be officers or qualified and skilled administrators in the legions. Some joined the vigiles, Rome’s police and firefighting force. Others were army surveyors, architects, and quarter masters.

There were many roles an evocatus could fill in the legions.

More often, the higher-ranking and skilled evocati came from the Praetorian Guard, though sometimes from the regular legions. It could be a plum job.

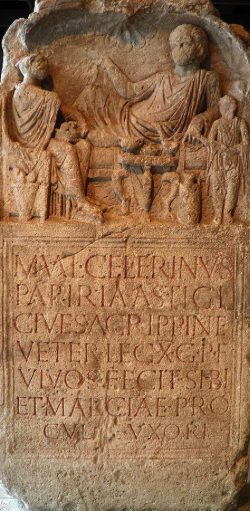

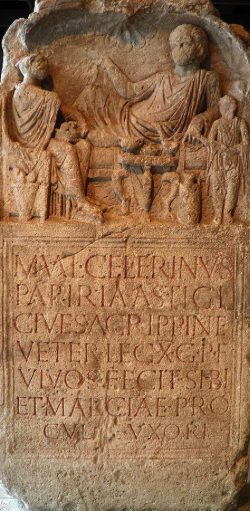

Grave stele of Marcus Valerius Celerinus, a veteran stationed on the German frontier

Grave Stele of Mira and Marcus Attius Rufus, veteran of II Adiutrix legion

Rome had a massive military force when you consider the regular legions, Praetorian Guard, and numerous auxiliary forces across the Empire. It has been estimated that about 250 men left each legion every year, and that about 15,000 soldiers retired from the Roman military annually.

That’s a huge number of trained troops to loose on a regular basis!

But Rome took care of it’s veterans for the most part. Men were rewarded accordingly for their years of service with money and lands. They could become valued and respected members of society, leaders in their own right. And even after their term as evocati, these veterans maintained that respect.

The Evocati of ancient Rome were, it seems, not only a skilled fighting force that could be called upon in times of need, but they were also a respected and important class in Roman society.

It may not have been a lavish lifestyle, but it does seem that life as an evocatus might have been better than most.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post about the Evocati in ancient Rome, and the research that went into creating one of the characters in The Dragon: Genesis.

If you have not already downloaded your FREE copy of The Dragon: Genesis, you can do so by CLICKING HERE.

Stay tuned for the next post in The World of The Dragon: Genesis when we will take a brief look at the joint rule of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Thank you for reading.