Greetings History and Mythology-Lovers!

We are heading back to Mycenae in this post to explore the domiciles of the Dead outside the walls of the ancient citadel, that is, the great tombs of Mycenae.

In our previous post, we walked through the entire fortress of Mycenae, discussed what it was like and how it felt to return to that ancient and, some would say, menacing, fortress after twenty years.

To read the previous post, Return to Mycenae, CLICK HERE.

Likewise, to go on a full tour of the archaeological site, check out our video Mycenae: A Tour of the Ancient Citadel, HERE.

Grave Circle ‘A’ within the walls of Mycenae’s citadel.

In our tour of the fortress, and the video, we explored what is known as ‘Grave Circle A’ which is located within the walls of Mycenae and was the location of the royal cemetery. It was here that graves pre-dating the Trojan War were located, and where many of the magnificent finds of Mycenae were discovered, including the golden death mask Heinrich Schliemann mistakenly took to be the ‘Face of Agamemnon’.

In this post, we are going outside the fortress walls of Mycenae to explore four of the most astonishing tombs of the Greek Bronze Age: the Lion Tomb, the Tomb of Aegisthus, the Tomb of Klytemnestra, and of course, the Treasury of Atreus.

But first, let us take a brief look at the types of tombs these represented.

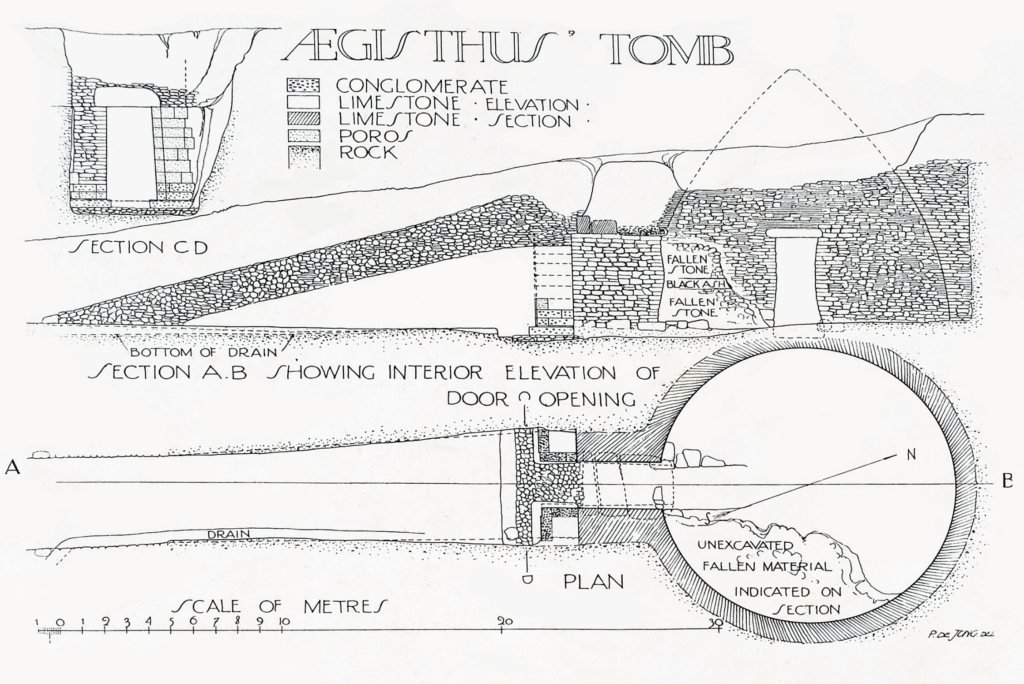

Parts of a Mycenaean chamber tomb, drawn up by Piet de Jong in 1920–1923

The graves located within ‘Grave Circle A’ are what are known as ‘shaft graves’ and, within the citadel, these were used to bury royalty with their astounding grave goods.

The tombs which we are looking at here are known as ‘chamber tombs’, of which there are many in the hills about Mycenae. These consisted of rock-cut chambers underground which were achieved by way of a passage called the dromos, which means ‘road’.

These chamber tombs could vary in size and shape, but when it came to the royal chamber tombs, or ‘beehive tombs’, they were meant to impress!

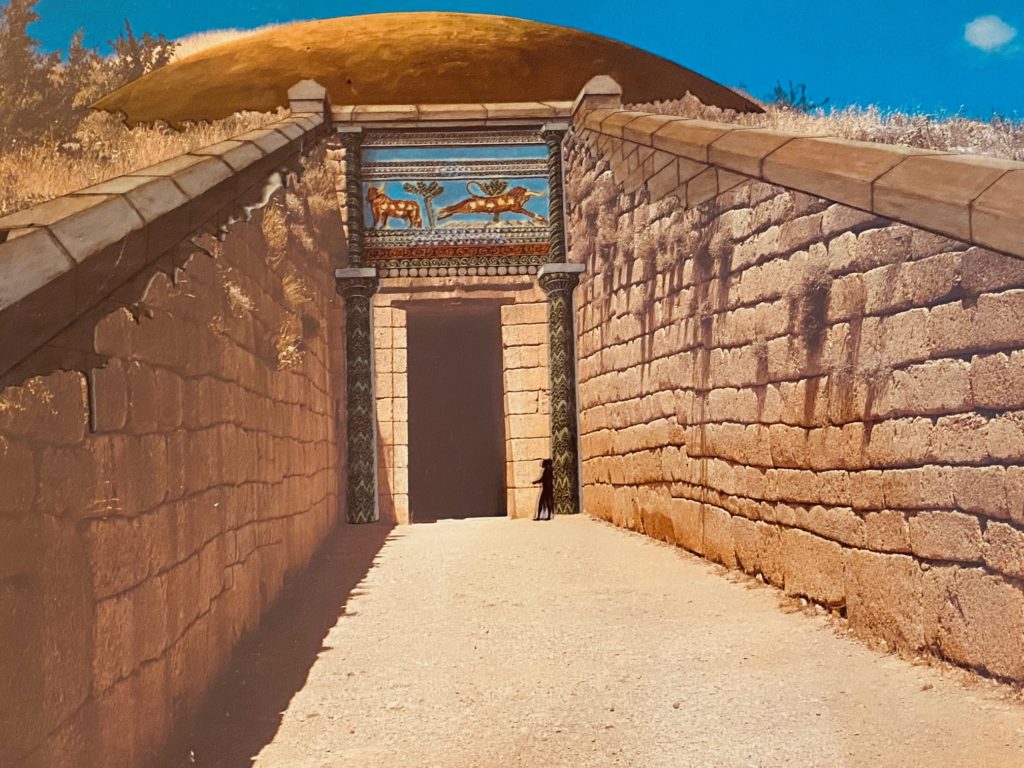

Artist representation of a Mycenaean tholos or ‘beehive’ tomb

The royal beehive tombs outside the walls of Mycenae were built into the hillsides and approached each by a long dromos, the largest being thirty-seven meters in length!

They had elaborate doorways and entranceways known as the stomion, beyond which are the vast, round burial chambers. These beehive tombs were roofed by a stone vault of horizontal rings which diminished in diameter until the roof closed at the top. They were true feats of engineering at the time. They were also referred to as tholos tombs because of their round shape. In some cases, such as the Lion Tomb, rectangular cists were cut into the floors of these tombs to accommodate bodies and valuable grave goods.

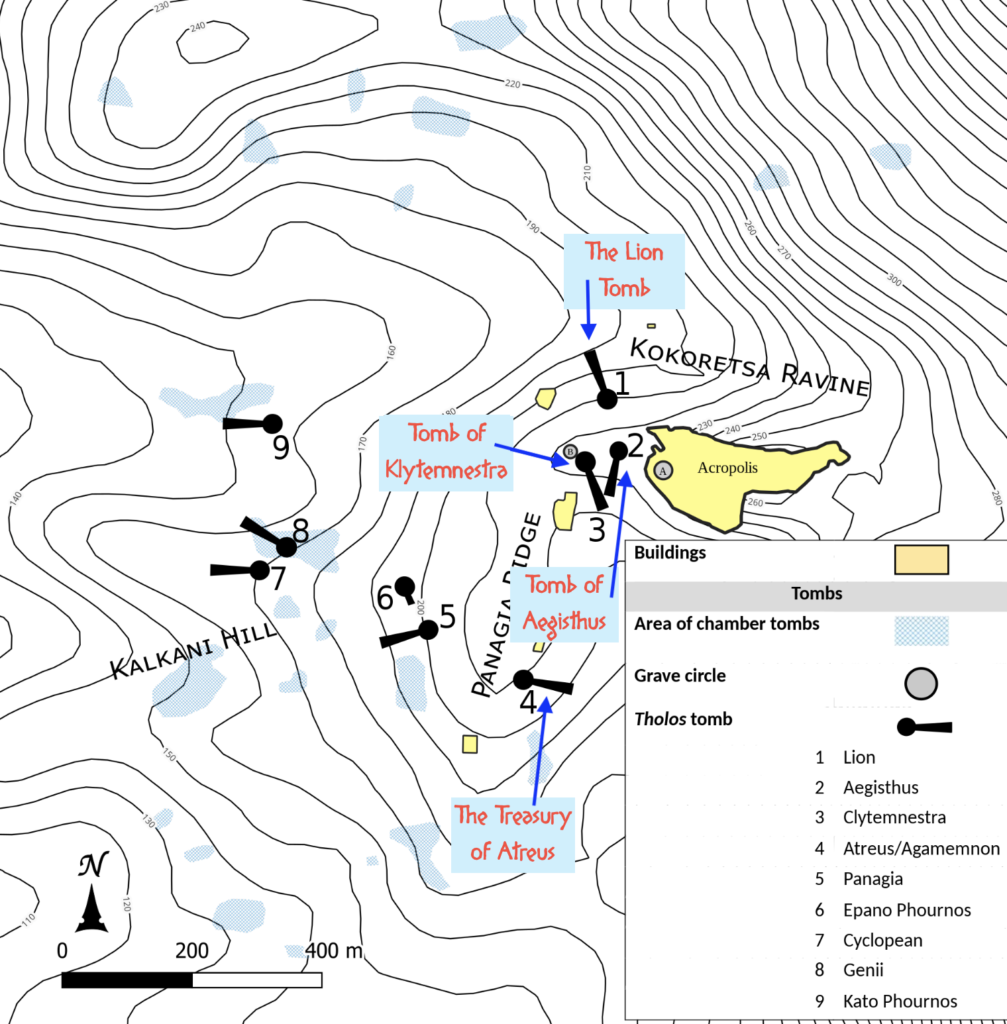

At Mycenae, there are approximately nine tholos or ‘beehive’ tombs that are known to date, dating from roughly around 1550 B.C.E to the end of the 13th century B.C.E.

Unfortunately, the grave robbers had cleaned all of them out, but the tombs themselves remained largely intact, and we are going to explore four of them today.

Map of Tombs at Mycenae

There is the grave of Atreus, along with the graves of such as returned with Agamemnon from Troy, and were murdered by Aegisthus after he had given them a banquet… Klytemnestra and Aegisthus were buried at some little distance from the wall. They were thought unworthy of a place within it, where lay Agamemnon himself and those who were murdered with him.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.16)

In his ‘Description of Greece’, the second century C.E. traveller and historian, Pausanias, makes mention of the tombs outside of the fortress walls, and three of them were on our list to visit after we finished our long, hot journey through the ruins of the fortress that dominated the area.

When we came out of the Lion Gate of Mycenae, cutting our way through the army of invading tourists, we turned left immediately and followed the dirt path down to where we knew there were two of the tombs we wanted to see.

Over twenty years ago, when we were last in Mycenae, these had been closed to the public because of their state of disrepair and the risk of stone falling upon one’s head. However, this time, we were thrilled to discover that these first two tombs, the tombs of Aegisthus and of Klytemnestra, were open!

Entrance to the ‘Tomb of Aegisthus’

The Tomb of Aegisthus was the first into which we ventured. It is the smaller tomb, and seemed to have born the brunt of time as much of the beehive roof was missing, leaving its golden sandstone walls open to sky. The chamber of this is still an impressive thirteen meters wide and the dromos is twenty-two meters long and five meters wide.

What struck me about this tomb – aside from the fact that this grand house of the dead may have been built for the murderer of Agamemnon – was the size of the lintel above the deep entrance.

There was a scaffold beneath this, supporting the entrance, which forced us to look carefully as we walked beneath and into the sun-drenched inner chamber.

The interior of the ‘Tomb of Aegisthus’ viewed from above with the plain of Argos in the distance.

When we emerged from the Tomb of Aegisthus, we turned right and went a short distance downhill to the site of the Tomb of Klytemnestra, King Agamemnon’s queen, and the mother of Electra and Orestes.

I would be lying if I didn’t note that I felt strange approaching the supposed tomb of this legendary character of Greek legend. Yes, Klytemnestra was said to be an adulterer with Aegisthus, but she was also daughter of King Tyndareus of Sparta, the older half-sister of the famed Helen, a jilted wife, and a tragically vengeful mother whose daughter was sacrificed by her husband.

I felt for the tragic, yet powerful spirit of Klytemnestra as I approached her final resting place.

The ‘Tomb of Klytemnestra’

The Tomb of Klytemnestra is thought to be the latest in date at Mycenae, constructed around 1220 B.C.E. The dromos of the tomb is thirty-seven meters long and six meters wide, and is lined with massive rectangular blocks.

The triangle over the lintel and the rest of the entrance would have been faced with marble slabs that were covered with elaborate carvings of spirals, rosettes and more, and the stromion seems to have contained a great wooden door about midway through its depth.

When we entered the Tomb of Klytemnestra, it was dark and sad, a feeling that was no doubt added to by what looked like a dead body at a glance, but which turned out to be a sad stray dog come to cool itself from the 45+ Celsius degree day.

The chamber of this tomb is only slightly larger that that of Aegisthus’ at thirteen and a half meters, but the beehive vault is fully intact and disappears into the darkness thirteen meters overhead.

This truly is an impressive monument and well-worth the visit if you have the strength after visiting the citadel. To be able to see even more, consider bringing a good flashlight the better to view the stonework inside.

Interior of the ‘Tomb of Klytemnestra’

After the Tomb of Klytemnestra, we climbed back up the hill toward the Lion Gate and then down toward the site museum.

To our surprise, there was yet another tholos tomb to the left of the museum. Without delay, we went down the rocky slope to its dromos, delighted to find that no one else was there.

Entrance to ‘The Lion Tomb’ of Mycenae

The ‘Lion Tomb’ is thus named because of its proximity to the famed ‘Lion Gate’ of Mycenae’s citadel. This is believed to have been constructed some time in the middle of the fourteenth century B.C.E. and has a dromos that is twenty-two meters long and almost five-and-a-half meters wide.

Sadly, the roof of this tomb is no longer intact, but it is estimated that its dome soared to a height of fifteen meters. It is still an impressive work, the chamber of which is fourteen meters wide and contained three pit graves which were found to be empty upon its discovery.

We stood in the middle of this chamber, our voices carrying around the bright, poros stone, and marvelled at its beauty, wondered who had been buried here. Had they been warriors of Mycenae, or members of the royal family who were not fit to be buried within the citadel, as Pausanias points out was the case for Klytemnestra and Aegisthus?

We will never know, but it certainly felt like a gift to be there with no one else around.

Interior of ‘The Lion Tomb’

From the Lion Tomb, we made our way to the museum to view many of the wonderful artifacts discovered at Mycenae. It is worth a visit, if anything to cool off from the Greek summer heat. The most important finds from Mycenae, including the golden death masks and bronze daggers, can be seen at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, which everyone should visit.

After a refreshing, and overpriced, cup of freshly squeezed Argive orange juice in the parking lot, we got in our car and bid farewell to Mycenae’s walls.

But not before one final stop.

A short distance down the road to the modern village of Mykines, you will find on the right the entrance to the great ‘Treasury of Atreus’, or, as the locals have called it in the past, the ‘Tomb of Agamemnon’.

The Treasury of Atreus is accessed by way of a separate entrance to the main archaeological site, but it is no less impressive.

Artist impression of the ‘Treasury of Atreus’

The Treasury of Atreus – named for the legendary son of Pelops and Hippodameia, and father of King Agamemnon, and King Menelaus of Sparta – is one of the most impressive monuments of the Mycenaean Age. It is completely preserved with only the decoration of the facade and interior missing.

Approaching the tomb, one is filled with a sense of awe and wonder. Who was truly buried here, and why did their people believe they deserved such a monument? What was the burial ceremony like, and what magnificent grave goods were interred with the dead, only to be stolen by grave robbers to disappear for all time?

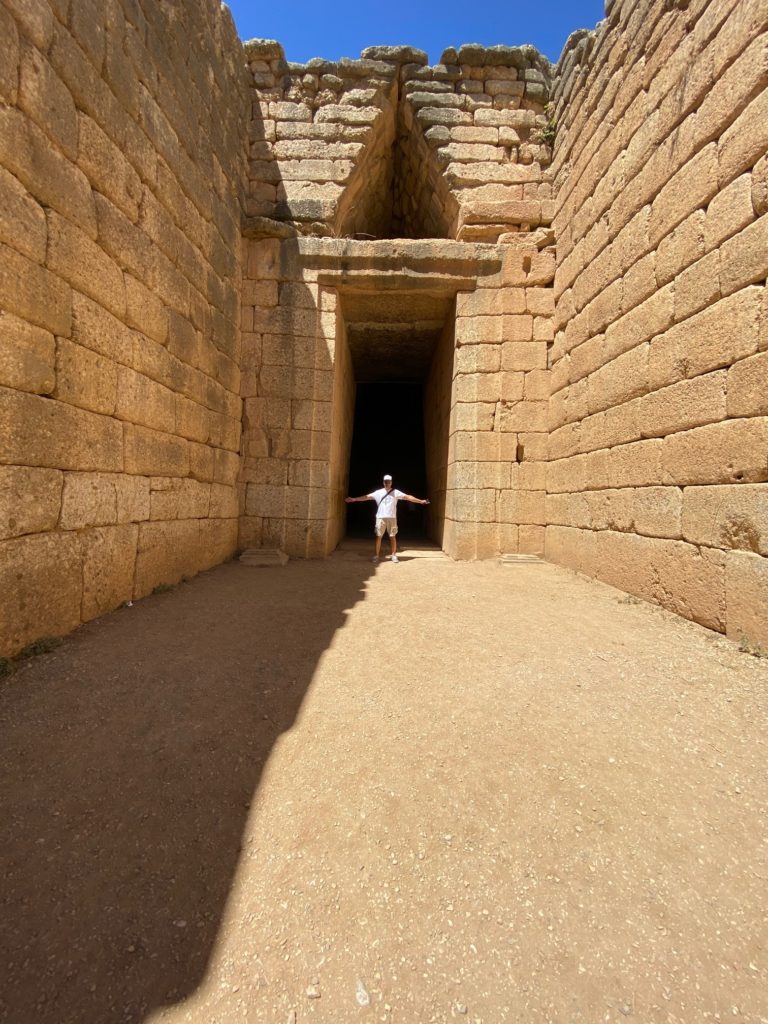

Standing in front of the Treasury of Atreus

The dromos leading to the tomb is cut into the rock of the hillside and is lined with massive rectangular blocks. It is thirty-six meters long and six meters wide, and the height of the entrance to the tomb is a stunning ten and a half meters high. The actually doorway measures just under five-and-a-half meters high and nearly three meters wide.

Passing beneath the lintel and the gaping triangle that would have been faced with ornate columns of green stone and a fresco or sculpture is an eerie experience. Remains of these can be seen in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

As we walked from the blistering heat and sunlight into the cool darkness of the tomb, it was indeed like stepping into another world, a world of the Dead.

Though there were many tourists by the time we reached the Treasury of Atreus, their presence seemed to be swallowed up by the tomb’s darkness, allowing us to observe our surroundings in relative peace.

Ceiling of the ‘Treasury of Atreus’

The main chamber of the tomb measures just over fourteen-and-a-half meters in diameter. It is a broad space one steps into upon entering the tomb, but the first thing that really draws the eye is the soaring ceiling of the tomb’s mesmerizing beehive construction.

The ceiling reached to a height of about thirteen-and-a-half meters high with thirty-three courses, or ‘rings’, of perfectly joined stones making up the construction. It is a true feat of engineering, that much is obvious, but it was also ornate, a home fit for kings in the Afterlife, though the ornamentation that would have decorated the circular walls is all gone, stolen since long before the visit of Pausanias in the second century C.E.

It is not only incredible to think that this tomb may have held the remains for such legendary figures as Atreus or Agamemnon but also, perhaps more so, it is stunning that it is still intact. The construction of this tomb has survived since the thirteenth century B.C.E.

The ante-chamber within the ‘Treasury of Atreus’

One feature that sets this particular Mycenaean chamber tomb apart from the others is the addition of an ante-chamber within the tomb. This large room is located to the right as one enters the treasury and was another burial chamber, in addition to the main chamber. The ante-chamber is blocked off and is deep and dark, but if you have a flashlight handy you can just make out the interior.

Once we finished explored the tomb, the air growing somewhat heavy within, we bid farewell to the shades of Atreus and Agamemnon, and made our way to the doorway and the light outside in the land of the living.

The tomb’s maw spat us out and we shielded our eyes as we walked in the sliver of shade offered by the walls of the dromos. It was time to leave Mycenae and the dead behind but, just as Orpheus could not help but turn to seek Eurydice at the gates of the Underworld, we also felt the need to turn around for one final glance at the magnificent entrance of the Treasury of Atreus.

The light outside the ‘Treasury of Atreus’

If you ever go to Mycenae, after exploring the citadel itself, be sure to leave time to visit the tombs of Mycenae, those great houses of the Dead that surround it.

They are some of the most stunning pieces of Mycenaean architecture that you will ever see, and when you emerge from them, from the deep darkness into the light, those tombs, and the shades of their inhabitants, will leave a lasting impression.

The ‘Lion Gate’ of Mycenae

If you are interested in visiting Mycenae for yourself, be sure to check out the deals that are available from Eagles and Dragons Publishing’s subsidiary, Ancient World Travel here:

https://www.ancientworldtravel.net/travel-resources-1

Check out our specially-curated deals on visits, tours (many from Athens) and tickets to Ancient Mycenae at the following link:

https://viator.tp.st/4DfkV2n1

Also, read the review of La Petite Planète, a lovely hotel (with an amazing terrace for dinner!) in the village of Mycenae where you can stay here:

https://www.ancientworldtravel.net/post/hotel-review-la-petite-planète-a-warm-welcome-in-the-shadow-of-ancient-mycenae

Lastly, check out the new video tour, The Tombs of Mycenae, on the Eagles and Dragons Publishing YouTube and Rumble channels.

Come with us as we explore the interior of these magnificent tombs of the Mycenaean age!

Thank you for watching, and thank you for reading!