This week, I wanted to leave behind the sad and depressing subject of the destruction of heritage to write about a site steeped in myth and legend – Tiryns.

“In the south-eastern corner of the plain of Argos, on the west and lowest and flattest of those rocky heights which here form a group, and rise like islands from the marshy plain, at a distance of 8 stadia, or about 1500 m. from the Gulf of Argos, lay the prehistoric citadel of Tiryns, now called Palaeocastron.” (Heinrich Schliemann; Tiryns; 1885)

I visited the site with family during the summer of 2002. It was a scorcher of a day and the cicadas were whirring full force by 9 a.m. Luckily, the heat meant that the place was devoid of visitors – the perfect time to explore.

Tiryns is one of those sites that you likely know about if you’ve studied classics, mythology or archaeology. Most people haven’t heard about it. It lies in the broad Argive plain, a fenced-in circuit wall along the road between Nafplio and Argos itself, surrounded by orange and olive groves.

At first glance, there is no hint that Tiryns was one of the major Mycenaean power centres of the Bronze Age. The cyclopean walls are big, impressive, but there have been times when I drove by and didn’t even notice it. Perhaps that was due to the madness of driving in Greece.

West wall of Tiryns

When we got out of the car, the hot wind whipped across the plain to envelope us and, once we paid our entrance fee at the small kiosk, it seemed to sweep us up the ramp to the citadel, and back in time.

Tiryns is a place of myth and legend. It’s been inhabited since the 7th millennium B.C., but by the Hellenistic and Roman periods, it was already in the death throes of a swift decline. Pausanius visited as a tourist in the 2nd century A.D.

“Going on from here [from Argos to Epidauros] and turning to the right, you come to the ruins of Tiryns… The wall, which is the only part of the ruins still remaining, is a work of the Cyclopes made of unwrought stones, each stone being so big that a pair of mules could not move the smallest from its place to the slightest degree. Long ago small stones were so inserted that each of them binds the large blocks firmly together.” (Pausanias; Description of Greece)

I’ve spoken before about the feel of a place of great antiquity. Tiryns is a truly ancient place.

In mythology, it was founded by Proitos, the brother of Akrisios, King of Argos and father of Danae, the mother of Perseus.

It was said that the walls of Tiryns were built by the Thracian Cyclopes of the ‘bellyhands’ clan before they built the walls of Mycenae and Argos. This is why this style is called ‘cyclopean walls’. They were known as the ‘bellyhands’ because that clan of the Cyclopes were said to have made their living through manual labour.

Perseus

It would have been a feat of tremendous strength to say the least, as each stone weighs several tons.

The association with Perseus is indirect as he acquired Tiryns after he killed his grandfather, Akrisios, but before he established Mycenae.

One of the most important mythological associations with Tiryns, however, is with Herakles, son of Zeus and Alkmene. The latter was the granddaughter of Perseus.

Let us go back to the time when Eurystheus was king of Mycenae, Tiryns and Argos (Note: Eurystheus was not a king of Athens, as portrayed in the recent film, Hercules.)

According to Apollodorus:

“Now it came to pass that after the battle with the Minyans Hercules was driven mad through the jealousy of Hera and flung his own children, whom he had by Megara, and two children of Iphicles into the fire; wherefore he condemned himself to exile, and was purified by Thespius, and repairing to Delphi he inquired of the god where he should dwell. The Pythian priestess then first called him Hercules, for hitherto he was called Alcides. And she told him to dwell in Tiryns, serving Eurystheus for twelve years and to perform the ten labours imposed on him, and so, she said, when the tasks were accomplished, he would be immortal.”(Apollodorus; Book II)

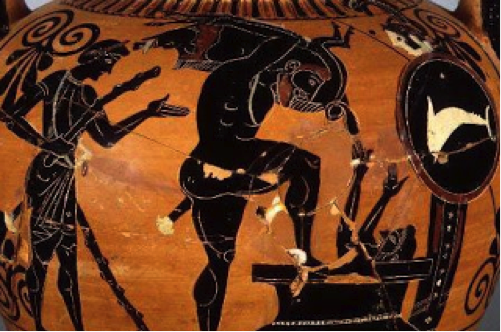

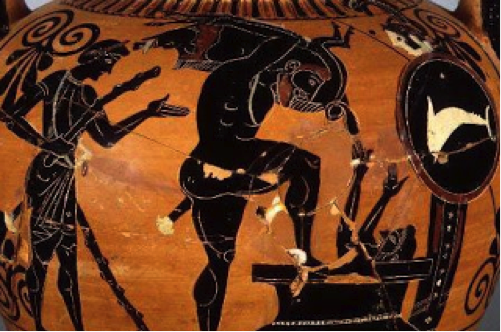

Herakles presents Eurystheus with the Erymanthian Boar

Herakles settled in Tiryns. His twelve tasks, or Labours, for Eurystheus are legendary and have been depicted in art for centuries throughout the ancient world. You can read a previous post about the triumphs of Herakles HERE.

Admittedly, when I visited Tiryns I had no idea of its associations with Perseus or Herakles. For me, a lot of research is sparked after visiting a site, and as a result, a follow-up visit is certainly in order.

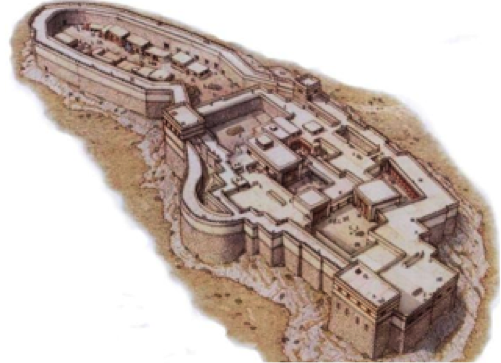

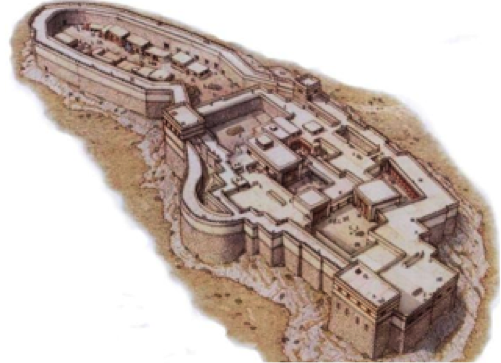

The citadel of Tiryns is about 28 metres high, 280 meters long, and it was built in three stages. In the 12th century B.C. it was destroyed by earthquake and fire but remained an important centre until the 7th century B.C. when it was a cult centre for the worship of Hera, Athena, and Herakles.

The Late Bronze Age (1600-1050 B.C.) was the height of Tiryns’ existence. It’s during this time that the cyclopean walls and most of the fortifications were built.

Today, as in the Bronze Age, one approaches the citadel on the east side. To get to the upper citadel, which was the location of the great megaron and palace, you must walk up a massive ramp that is 47 metres long and 4.70 metres wide. This would have led to the main wooden gates.

The Great Gate

Once past the gates, you walk along what was a corridor that led to the Great Gate which was flanked by a tall tower. The Great Gate was almost the size of the famous Lion Gate of Mycenae, and would have proved an imposing structure.

When I was walking along the ramp, looking up at the remains of the massive walls and the tower, I could imagine warriors in bronze, with boar’s tusk helmets, looking down on me, with spears or bows in hand.

Even though the citadel contained a luxurious palace and baths, this would not have been an easy fortress to storm.

Once you attain the top, you find yourself on a level area looking out over the site – the upper, middle and lower citadels.

Artist Reconstruction of the Citadel of Tiryns

There is not much left in the way of intact walls when it comes to the palace but you can see the outlines of the many rooms, especially the courtyards and the great megaron where the King of Tiryns held court and had his throne on a raised platform overlooking the central hearth.

Imagine Herakles approaching Eurystheus to ask him what his next labour was to be, in this room. This was the heart of the palace. Other rooms would have included residences, a second megaron and even a bath, the floor of which is made up of a huge monolith.

I was a bit dazed, standing there in the heat, looking on the remains of this site with awe. It’s so very old and the ruins only hint at what was a luxurious, but defensible, palace. And that was just the upper citadel.

The middle citadel, 2 m lower, provided access to the defences and may even have contained a pottery kiln. The lower citadel, which is also surrounded by walls, may have been used as a refuge for the people of Tiryns town on the west side, in times of need.

Reconstructed Fescoe from Tiryns’ Palace

At one point, when I was looking about the gravelly surface of the court, I spotted tiny bits of pottery. Of course, I bent down to get a closer look and picked up a shard with three black lines painted across it. Before I could contemplate the age of this piece, a loud whistle blew and a site person seemingly emerged from the rocks like an asp hiding from the midday sun. “No touching!” I heard, in heavily accented English.

Good thing she didn’t have a spear or bow.

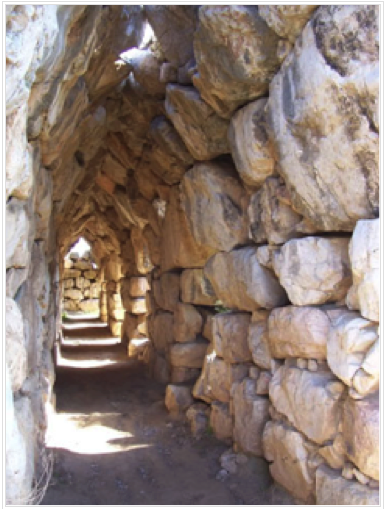

After leaving the upper citadel, we walked down some steps to what is my favourite part of the site – the east galaria.

This beautiful arched tunnel is still intact, and with the sun shining from above, it was suffused with soft light. I immediately imagined a Mycenaean queen strolling between the light and shadow of this place, or a determined king on his way to a war council, his cloak flapping behind him, bronze-clad guards in his wake.

The East Galaria

Such is the power of a site like this to fire the imagination.

Back to the present.

It’s funny, but whenever I find myself fed up with cold winter days where I live, I think back to that scorched but brilliant day at Tiryns, and smile. I feel warmth again. I enjoy the glint of the sun radiating off of the stone, and its sparkle far out in the Gulf of Argos.

This ancient citadel is a welcoming place where history and myth are entwined, comfortable allies. I certainly hope my path leads me there again one day soon.

Thank you for reading.

What is your favourite ancient site with mythological and legendary links?

Let us know in the comments below.