Troy

Ancient Orphanage – The Sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron

“Muse, sing of Artemis, sister of the Far-Shooter, the virgin who delights in arrows…”

(Homeric Hymn IX)

It was early January in Attica, Greece, a few years ago. I remember it clearly.

I drove out of Athens on a grey day that could dampen anyone’s post-holiday spirits.

The New Year had come and gone, copious amounts of food and wine having been consumed. A new adventure was needed.

My destination on that rainy day? – The Sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron.

I drove the forty two kilometres from Athens to Brauron, passing dark, rocky mountains and hills covered in deep green foliage. Greece is a very different place in the winter. This was another one of those journeys in which I didn’t know what to expect.

I had never heard of Brauron, or of an Attic sanctuary of Artemis, Goddess of the Hunt, protector of young girls and women in childbirth.

The car splashed its way over tiny roads and through villages lost to the outside world. As I drove past, a few heads poked out of windows to follow my progress as if in some eerie back-woods movie setting.

Finally, I came to my destination. I parked the car on the side of the road and stopped for a moment to listen to the pattering of the rain on the roof. I wiped my foggy window and could just make out a set of grey columns standing sentry in the rain. I put on my rain gear and jumped out.

The gate to the site was open and no one was at the booth. So I walked into the sanctuary.

My initial reaction was one of sadness. I don’t know why, but the rain seemed fitting then, as though the gods wept for something.

This is a place of great antiquity.

Supposedly, Brauron has been inhabited since the early Mycenaean age. Legend has it that the sanctuary of Artemis was established by none other than Iphegeneia, the daughter of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae.

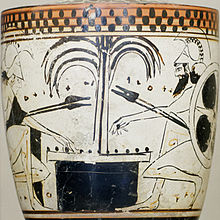

Iphegeneia is brought to Aulis in this painting:

Here is a brief summary for those of you who do not know her story. The Greek army, led by Agamemnon, was stuck at Aulis because of bad weather which prevented them from setting out for Troy.

This was said to be due to an offense done to Artemis. Calchas, the high king’s seer, told Agamemnon that the only way for the goddess to be appeased and for the winds to abate was for him to sacrifice his own daughter, Iphigeneia, to the goddess.

The young girl was brought to Aulis under the pretence that she was to marry the hero Achilles, and when she arrived, Agamemnon did the unthinkable.

Euripides opens his play Ipheigeneia in Tauris. Iphegeneia speaks:

“Child of the man of torment and of pride

Tantalid Pelops bore a royal bride

On flying steeds from Pisa. Thence did spring

Atreus: from Atreus, linked king with king,

Menelaus, Agamemnon. His am I

And Clytemnestra’s child: whom cruelly

At Aulis, where the strait of the shifting blue

Frets with quick winds, for Helen’s sake he slew,

Or thinks to have slain; such sacrifice he swore

To Artemis on that deep-bosomed shore.

For there Lord Agamemnon, hot with joy

To win for Greece the crown of conquered Troy,

For Menelaus’ sake through all distress

Pursuing Helen’s vanished loveliness,

Gathered his thousand ships from every coast

Of Hellas: when there fell on that great host

Storms and despair of sailing. Then the King

Sought signs of fire, and Calchas answering

Spake thus: “O Lord of Hellas, from this shore

No ship of thine may move for evermore,

Till Artemis receive in gift of blood

Thy child, Iphegeneia. Long hath stood

Thy vow, to pay to Her that bringeth light

Whatever birth most fair by day or night

The year should bring. That year thy queen did

Bear

A child – whom here I name of all most fair.

See that she die.”

So from my mother’s side

By lies Odysseus won me, to be bride

In Aulis to Achilles. When I came,

They took me and above the altar flame

Held, and the sword was swinging to the gash,

When, lo, out of their vision in a flash

Artemis rapt me, leaving in my place

A deer to bleed; and on through a great space

Of shining sky upbore and in this town

Of Tauris the Unfriended set me down;

Where o’er a savage people savagely

King Thoas rules. This is her sanctuary

And I her priestess. Therefore, by the rite

Of worship here, wherein she hath delight –

Though fair in naught but name. …But Artemis

Is near; I speak no further…”

(Iphegeneia in Tauris; Euripides; c.413 B.C)

Even in translation, the words Euripides gives to this tragic girl are powerful and moving.

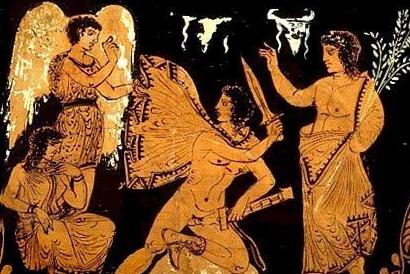

Thankfully, the goddess Artemis is said to have substituted another sacrifice for Iphegeneia, and taken her far away to be a priestess in her temple at Tauris, in the Crimea. She spent years there away from her mother, Clytemnestra, and her brother, Orestes. She also lived knowing her own father had been ready to end her life.

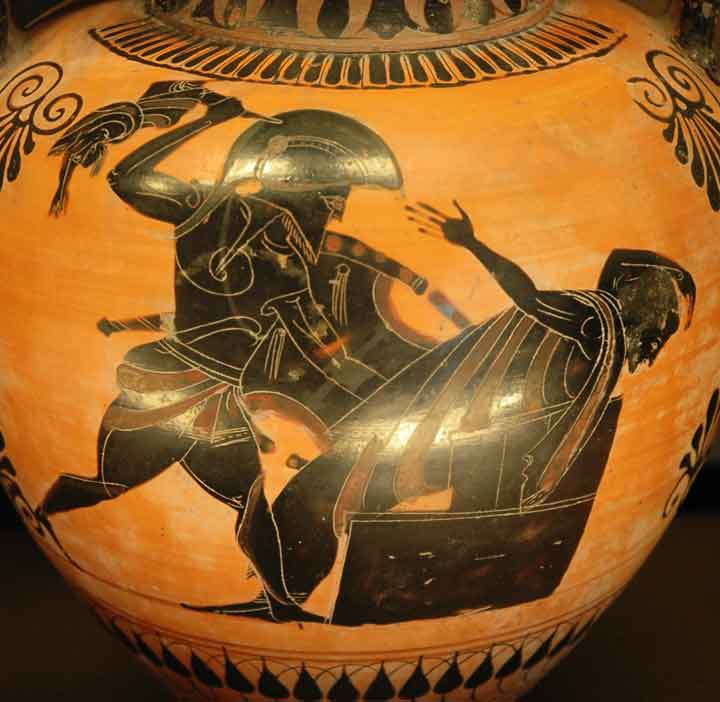

The Trojan War played itself out, and Agamemnon made his way home to be murdered by Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus. About seven years later, Orestes, the son of Agamemnon, returns from Athens and with encouragement from his sister, Electra, kills his mother and her lover.

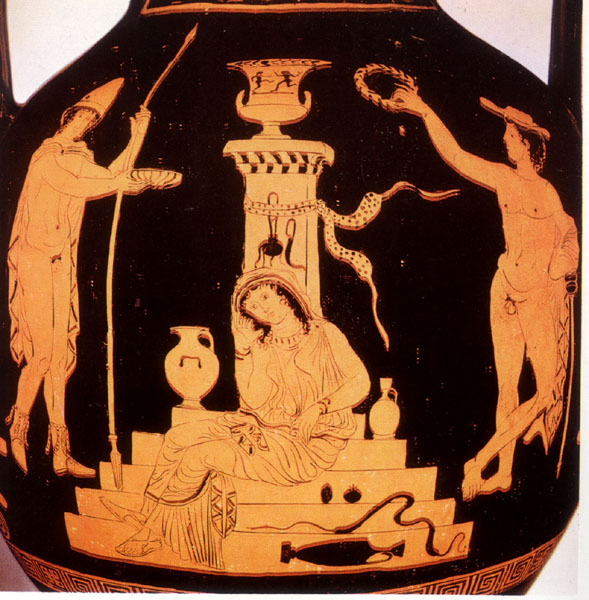

Orestes is pursued by the Furies for his deeds, but then Apollo orders him to go to Tauris in order to take the wooden cult statue of Artemis and bring it back to Athens. Euripides tells how Orestes goes to Tauris and eventually sees his sister Iphegeneia there. They are reunited and she helps him to take the statue and together they return to Attica where she establishes the Sanctuary of Artemis.

Here, the Goddess Athena speaks to Iphegeneia before she leaves Tauris:

“…Iphegeneia, by the stair

Of Brauron in the rocks, the Key shalt bear

Of Artemis. There shalt thou live and die,

And there have burial. And a gift shall lie

Above thy shrine, fair raiment undefiled

Left upon earth by mothers dead with child.”

(Iphegeneia in Tauris; Euripides)

Iphegeheia is said to have spent the remainder of her days at Brauron.

The cult of Artemis at Brauron died out after the Mycenaean age but was re-established from the 9th century B.C. on. Eventually, the cult of Artemis was brought to Athens. After that, there was a procession every four years from the Temple of Artemis Brauronia on the Athenian Acropolis to Brauron, in honour of the goddess and her priestess, Iphegeneia.

But what was the purpose of the sanctuary at Brauron besides being a place to honour of the goddess?

It seems that the sanctuary also functioned as a sort of orphanage or fostering place for young girls who served the goddess from about five to ten years of age. They performed rituals which included sacred dances in which they acted like bears. In fact, the girls were called arktoi, or ‘the bears’. This odd tradition of the bears is said to commemorate the slaying of one of Artemis’ sacred bears by one of the girls’ brothers. The Arkteia was a service to the goddess in which young girls would transition from childhood to puberty and marriageable age.

At Brauron, Artemis was worshipped as a protector of girls and women in childbirth. Women who survived childbirth dedicated a set of clothes to the goddess. The clothes of women who died in childbirth were, in turn, dedicated to Iphegeneia.

I imagine a lot of hope springing up in this place, but also much sadness.

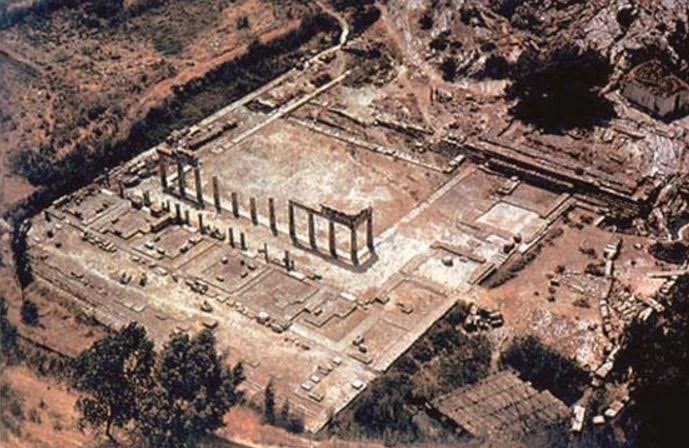

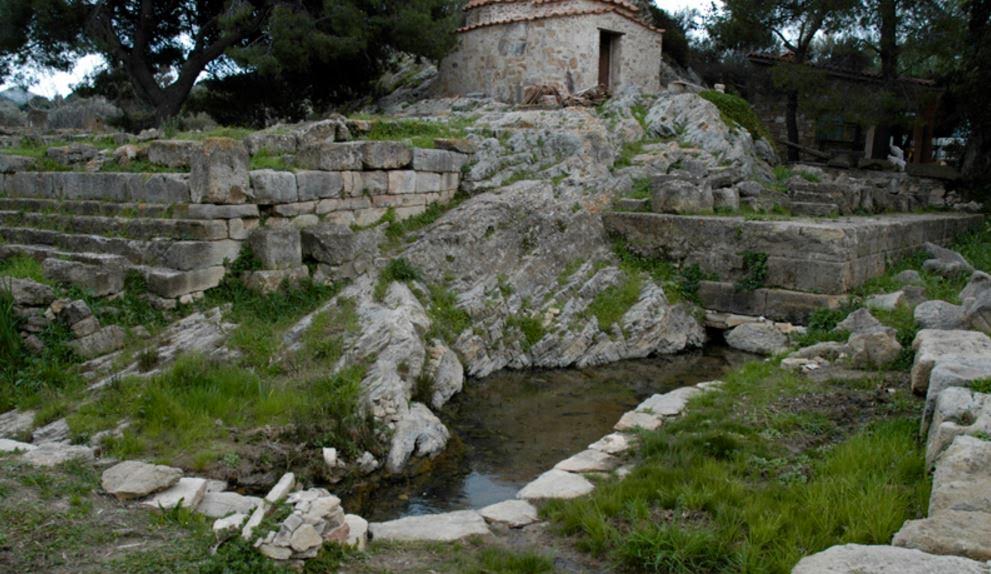

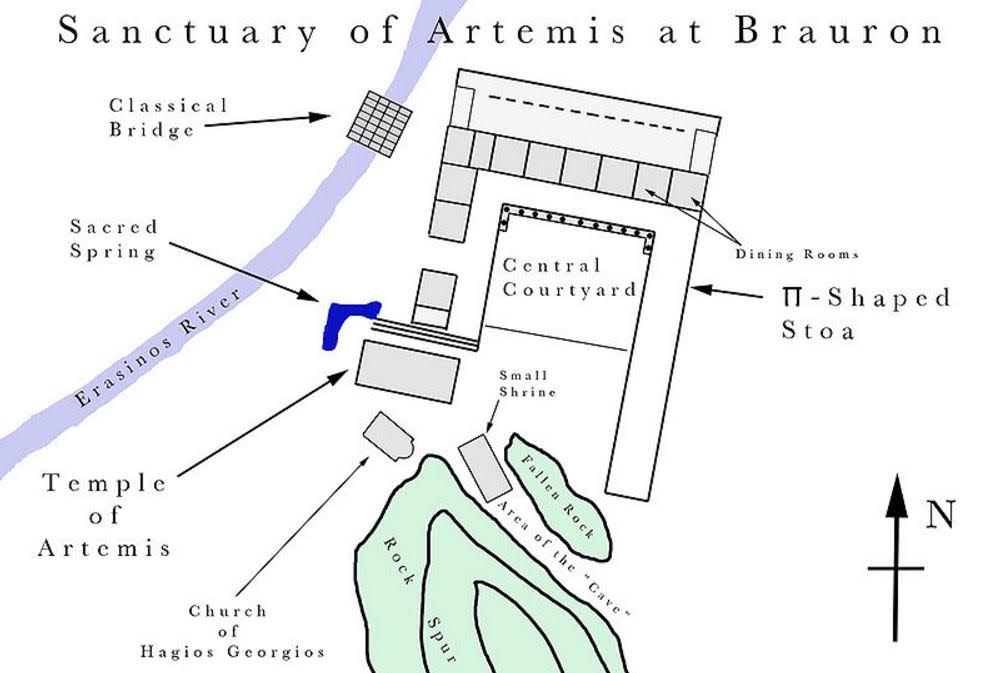

Once you cross the 5th century bridge into the sanctuary, you come to the unusual p-shaped stoa which has what are thought to be dining rooms or, more likely, rooms for the girls living within the sanctuary. Inside, you can still see places where their sleeping pallets might have been and holes carved into the marble where the door posts rested.

The stoa is known as the ‘Stoa of Bears’.

I walked along the paving slabs on that rainy day, peeking into the small rooms and wondering at the children who would have been there. Were they peasants or nobility? Were their parents killed by war or plague? Were they sent there in fulfillment of a vow? Who did they have left in the world?

It must have been a frightening prospect to leave the safety of the sanctuary as well. What must a young girl have thought when she turned ten and knew that her time had come to perform the sacred dance one last time before going out into the world. Ancient Greece was not so kind a place for girls or women. They were seen as vessels to be kept indoors.

A good thing they had Artemis to look over them, and to see them through childbirth.

The stoa courtyard was overgrown with sodden grass when I was there, and the ruins of the small Temple of Artemis were minimal.

As I made my way through the site, I eventually came to a small cave-like recess that was supposed to be a shrine to Iphegeneia, that sad daughter of Agamemnon.

The rain stopped here, and the skin prickled on the back of my neck.

For how long had this first priestess of Brauron been honoured here? Ages, it seemed.

I let my imagination go in the sanctuary and could hear the laughter of little girls playing, or their lonely cries upon their straw pallets. I could see them mimicking the bears for which they were named, and hear the sound of their voices raised in song to Artemis, their protectress.

From Brauron’s beginnings as a sacred site, each of those little girls likely stood where I was standing and remembered Iphegeneia and her plight. I thought of how they must have wept at her sad story and perhaps felt better about their own lives that led them to that place in the green hills of Attica.

The Sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron is a very special place.

When I crossed back over that classical bridge and made my way back to the car, I turned at the gate and looked back through the driving rain one last time.

Usually, when I leave an ancient site or sanctuary, I feel uplifted and at peace.

Not so with Brauron.

Upon leaving Brauron, my heart was in turmoil, and it still is when I think back on that place.

It’s place of conflicting emotions wrapped in myth and legend.

It’s a great comfort in some ways to know that this was a place where young girls were protected, watched over by their patron goddess who saved the first priestess – this, in an ancient, male-dominated world of war and superstition.

On the other hand, as I turned my back on the dark columns and sodden earth of the sanctuary, my sole, sad thought was for Iphegeneia whose father was so determined to sail for Troy that he was willing to perform such a heinous and tragic act.

Thus do myth, legend, and history combine to shape our view of the places of the past.

Thank you for reading.

The Links Between History and Mythology – A Guest Post by Luciana Cavallaro

Today I have a special guest on the blog.

Luciana Cavallaro is the author of a series of mythological retellings from the perspectives of some fascinating women in Greek myth.

When I read her book, The Curse of Troy, I knew that I wanted to have her write a guest post for Writing the Past. Luciana has a wonderfully unique style, and she gives these accursed women of Greek myth a voice that you may not have heard before.

So, without further ado, a big welcome to author, Luciana Cavallaro!

First, I’d like to thank Adam for inviting me to be a guest blogger. I’ve been following Adam’s blog for years now and enjoy reading about the Roman history, expansion and legacy they’ve left behind and learning about King Arthur and Medieval England. The latter is not one of my strongest or favourite periods of history, but I do enjoy reading Adam’s articles. I also want to apologise to Adam. He asked me last year to be a guest blogger and at the time I was finishing up my book and then time got away from me.

Let’s get into it

I’m a bit of a fan of mythology, in particular Greek myth, but I’m not an expert or purport to be one. I love the stories, learned a great deal from them and continue to do so. What I particularly enjoy are the links between the myths and historical fact.

Before I get into that, let’s address what mythology is. Here’s a dictionary meaning:

Mythology is a body of myths, especially one associated with a particular culture, person, etc. (Collins Concise Dictionary, 1989)

I prefer Joseph Campbell’s explanation:

There is a mythology that relates you to your nature and to the natural world, of which you’re a part. And there is the mythology that is strictly sociological, linking you to a particular society.

(Interview with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth, 1986)

Myths are cultural as is history. If one digs (pardon the pun) deep enough, there is a correlation between the story and fact. Let’s take Jason of the Argonauts and his search for the Golden Fleece. In the Republic of Georgia, once annexed by Russia, the fleece of a sheep was used to trap golden grains dug from the river, or placed in the river banks and used in the same way.

Here’s a great article on this: Legend of the Golden Fleece was REAL: Greek myth originated near the Black Sea where miners used sheepskin to filter gold from mountain streams, geologists claim

I also watched a documentary of an Australian photo journalist who was trying to find the cities Alexander the Great founded in the Middle East. He watched Afghan miners use this technique to find gold in the riverbeds 4000 years on.

The journey from Jason’s home of Iolkos (Thessaly) to Georgia some distance away was dangerous. It is possible the story of the skills and craftsmanship of the Colchians who developed smelting and casting metals for agriculture and making jewellery found their way to Greece. This was something the ancient Greeks wanted, and the gold.

“Jason Pelias Louvre K127” by Underworld Painter – Marie-Lan Nguyen (2006) Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

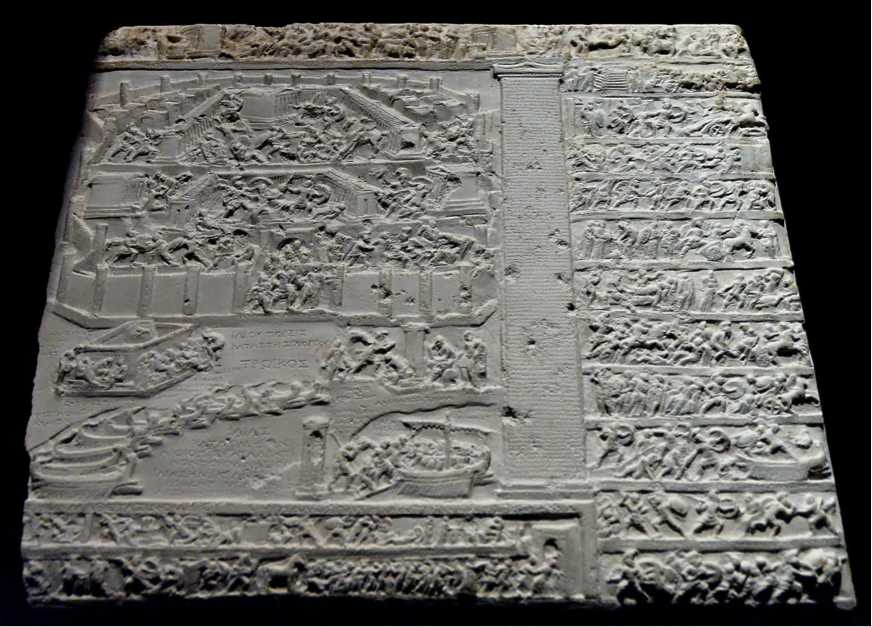

Another is the great story of Troy in Homer’s Iliad, which is a famous tourist site, and I did get to see. It is massive just as Homer stated. The lofty walls the Greeks couldn’t penetrate are there, and what is left is tall and slopes inwards. Hittite texts confirmed the site of Ilios, which they called Wilusa and identified Alaksandu/Alexander as one of the city’s kings. Alexander was the Greeks’ name for Paris. The texts also mention an invading force from the west, Ahhiyawa, that closely resembles Homer’s name for the Greeks, Achaeans. What historians have concluded is Homer’s story is a collective memory of the various invasions on Troy over centuries and its eventual downfall.

Hittite tablet recounting the events of the fall of Troy by Unknown – Jastrow (2006). Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The fact that the site of Troy exists, as does Mycenae, home of King Agamemnon, does give credence to the mythologies. But like all stories, you can’t let facts get in the way of telling a good tale.

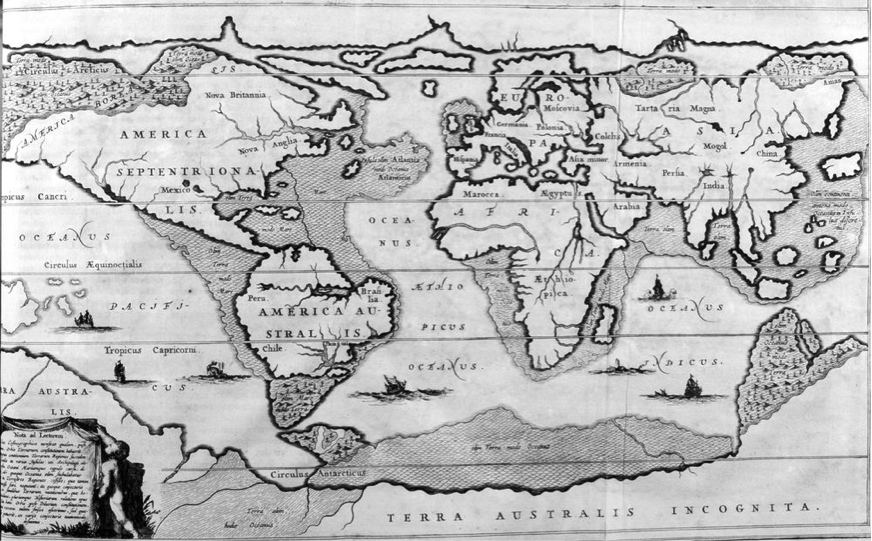

I do believe the more we delve into the myths, the more facts we’ll find in history. As with the current series I’m writing on my blog Eternal Atlantis, on the Atlantis myth, I believe such a place did exist. Like Homer’s Iliad, the enduring legend of Atlantis is a conglomeration of memories and oral histories to explain the rise and fall of a mighty empire. Look through the timeline of history and you will find many periods of great empires and their demise, either through war or a natural disaster.

Kircher’s 1675 map of the world after the Great Flood. The location of Atlantis is marked in the Atlantic Ocean. (Print Collector/Getty Images)

Myths, like all stories, have morals and a message to relate. One day, I hope we will be smarter and take heed of these so we don’t keep repeating these transgressions. In a hundred or thousand years to come, people will question our mythology. What mythology will we leave behind?

I’d love to know your thoughts on the veracity of myths in our history.

I’d like to thank Luciana for taking the time to write this fascinating post for us. I’m so jealous of her trip to Troy, a place which I have wanted to visit for a long time. Ah, someday…

Mythology is truly fascinating, and there is a lifetime and more of stories for us to enjoy and learn from.

If you enjoy mythology as much as I do, you’ll definitely want to check out Luciana’s book, Accursed Women, or pick up one of the many short stories she has out. She also has a new book entitled Search for the Golden Serpent which I’m looking forward to reading.

Also, be sure to sign up for her E-bulletin so that you can receive her very interesting blog posts to your e-mail. By signing up, you’ll receive The Curse of Troy for FREE!

I always look forward to reading her posts as they are a fantastic escape from the everyday. The blog series on Atlantis is titantic!

Please leave any questions or comments for Luciana in the comments below, and, once again, thank you for reading…