SPOILER ALERT!

Before you read further…

If you have not yet read Heart of Fire – A Novel of the Ancient Olympics, and you are planning on doing so, you may wish to read the book first, before you continue with this blog post.

The events discussed here, in Part 8 of The World of Heart of Fire, involve the climax of the book, and so your experience in reading the story might be lessened somewhat if you continue.

However, if you have already read Heart of Fire, or are just here to read about the history, then please do carry on. I hope you enjoy it!

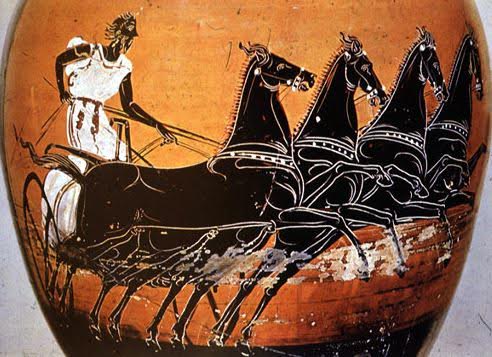

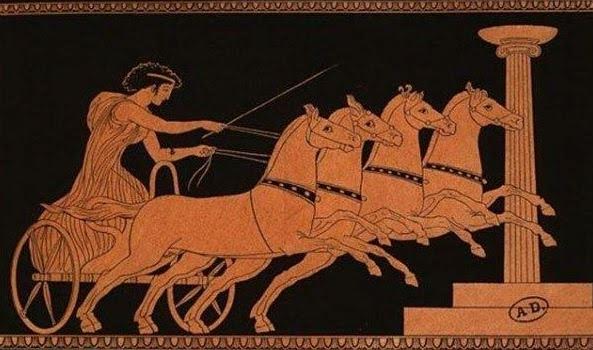

In Part 7 of this blog series, we discussed chariot racing at the ancient Olympics. However, we did not touch on why that event was so pivotal to the Olympiad of 396 B.C.

We have mentioned before how only men were permitted to compete in the Olympic Games in the ancient world. However, there was one event in which women were permitted to compete – the chariot race.

Though women were not allowed to enter the Olympic sanctuary during the Games, they were allowed to compete as the owners and trainers of horses in the chariot races.

It was in the year 396 B.C. that Princess Kyniska of Sparta exploded onto the scene and made Olympic history.

Goddess Artemis

The very first time I read about Kyniska (also spelled Cynisca), I knew I had to write this book. There was absolutely no doubt in my mind. I was inspired by her story, though very little detail has come down to us about this fascinating woman who rocked the world of men.

You see, in 396 B.C. Kyniska was the first woman to compete in and win in the marquee tethrippon event at Olympia, the four-horse chariot race.

At this Olympiad, which came on the tail of several years of brutal civil war among the Greeks, and at a time when many Greek city-states reviled Sparta, Kyniska came forward like a force of nature.

But who was this amazing woman?

Kyniska of Sparta was the daughter of King Archidamus II of Sparta (476-427 B.C.), the Eurypontid King of Sparta. She was also the half-sister of King Agis, and sister to King Agesilaus II (444-360 B.C.) who waged war on both the Persians and his fellow Greeks.

Archidamus left sons when he died, of whom Agis was the elder and inherited the throne instead of Agesilaus. Archidamus had also a daughter, whose name was Cynisca; she was exceedingly ambitious to succeed at the Olympic games, and was the first woman to breed horses and the first to win an Olympic victory. After Cynisca other women, especially women of Lacedaemon, have won Olympic victories, but none of them was more distinguished for their victories than she.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, 3.8)

Artist impression of Kyniska driving chariot

It is believed that Kyniska was born sometime around 440 B.C. in Sparta and, unlike other Greek women beyond Sparta, she grew up training herself physically and mentally as was expected of strong, Spartan women.

In Sparta, it was believed the woman should be fit and healthy as well, and they trained naked at sports, riding and hunting, just like the men. In Sparta’s eyes, how else could they give birth to perfect Spartan warriors?

Young Spartans Exercising (Edgar Degas)

But Kyniska was destined for other things that giving birth to new Spartan warriors.

She was an expert equestrian, a sort of ancient horse-whisperer learned in the breeding and training of horses. As the wealthy daughter of a king, the rearing of horses would have been accessible to her.

After years of raising and training horses, Kyniska finally entered a team in the great four-horse chariot race of the 396 B.C. Olympics.

Sadly, the ancient sources mention Kyniska only in passing, and even then, with the exception of Pausanias, it is in relation to her brother, King Agesilaus II.

Xenophon, the great leader of the 10,000, and author of the ancient work On Horsemanship, mentions Kyniska in his work on his very good friend Agesilaus:

Surely, too, he [King Agesilaus] did what was seemly and dignified when he adorned his own estate with works and possessions worthy of a man, keeping many hounds and war horses, but persuaded his sister Cynisca to breed chariot horses, and showed by her victory that such a stud marks the owner as a person of wealth, but not necessarily of merit. How clearly his true nobility comes out in his opinion that a victory in the chariot race over private citizens would add not a whit to his renown; but if he held the first place in the affection of the people, gained the most friends and best all over the world, outstripped all others in serving his fatherland and his comrades and in punishing his adversaries, then he would be victor in the noblest and most splendid contests, and would gain high renown both in life and after death.

(Xenophon, Agesilaus 9)

We need to remember that in this man’s world, the men wrote the history, and as a friend of Agesilaus’, Xenophon would have sought to please the king in his writing.

It was said that Agesilaus told Kyniska to compete in the Olympics simply to win and then discredit the sport of chariot racing by showing that even a woman could win it. Given Agesilaus’ character, this seems more likely than a willingness to display his sister’s abilities, or to raise the status of women in general.

At this time in history, in Ancient Greece, even a Spartan woman was just a woman. Men ruled this world, and women had their place.

But that is why Kyniska’s story is so compelling!

Sure, it’s easy from our modern vantage point to romanticize Kyniska and her achievements, but let us remember that, even though she did not drive the chariot, she would have met resistance every step of the way.

In Sparta, the use of horses for war was not common, and chariot racing as a sport was frowned upon. Kyniska must have been quite determined to go to the Olympic Games if she raised and trained her chariot team.

If King Agesilaus was seeking to discredit the sport of chariot racing by having his sister compete, his attempts were in vain. At that time, chariot racing was the marquee event of the Olympiad, and it only grew in popularity over the years until it reached its peak as a sport centuries later in the hippodromes of Rome and Constantinople.

Roman Chariot Race in the Circus Maxiums

When Kyniska of Sparta arrived outside the sanctuary of Olympia in 396 B.C. to have her team compete in the Olympic Games, one can imagine the rich men of every other city-state, perhaps even her own, scoffing at the thought of such a thing, of a woman owning, breeding, and training horses.

But it seems the gods were with Kyniska of Sparta on that fateful summer day in 396. Her team drove to victory in the Olympic tethrippon, and surely, the shockwaves of such a triumph must have been felt across the Greek world, a world in which an Olympic victory could bring a mortal as close as possible to immortality.

Old print of Kyniska

As was the right of every Olympic victor, Kyniska was permitted to erect a victory bronze for herself in the Altis of Olympia, along with the images of the champions of ages past.

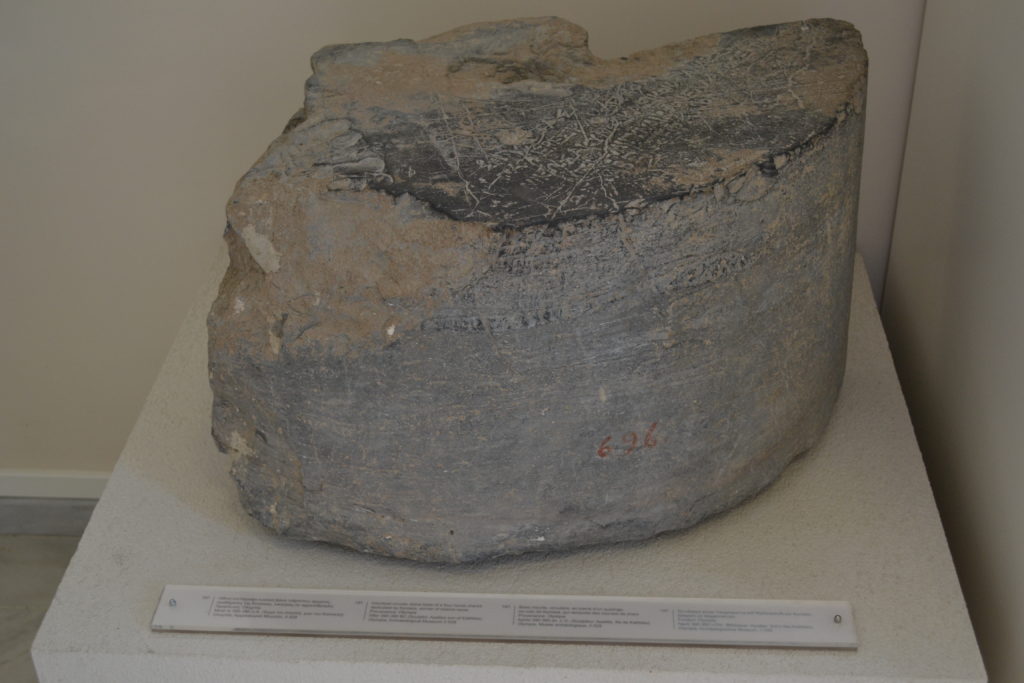

According to Pausanias, her statues included one of herself, and a bronze equestrian group. As fortune would have it, the statue base survived to give us this inscription:

Kings of Sparta are my father and brothers,

Kyniska, victorious with a chariot of swift-footed horses,

have erected this statue. I declare myself the only woman

in all Hellas to have won this crown.

Apelleas son of Kallikles made it.

From these few words, it seems obvious that Kyniska was proud, and well-aware of the enormity of her victory. She had previously been a winner in the foot race of the Heraian Games, and now she was an Olympic champion, the only woman ever to have won the sacred olive crown.

I have chills writing about this, to think that that was the moment in which the door to athletic competition had been opened for women, and in such a masculine world. It is humbling, and mind-blowing, and it reminds me of why I wanted to write Heart of Fire.

As if to solidify her immortality, Kyniska returned to Olympia in 392 B.C. to claim a second victory in the tethrippon.

After this Spartan princess, other women, not only of Sparta, entered and won in the chariot races of Olympia and other games, one of them Euryleonis, in 368 B.C., who makes an appearance in the story of Heart of Fire. The victors were not only women of Sparta, like Kyniska and Euryleonis, but women of other city-states, including Belistiche, Zeuxo, Encrateia, Hermione, Timareta, Theodota of Elis, and Cassia.

Inscribed base for the bronze victory statue commemorating Kyniska’s victory at the Olympic Games. It is now located in a small room at the Museum of the Olympic Games in ancient Olympia, Greece. It was amazing to see this piece of stone that represented such an earth-shattering change in Olympic history!

Kyniska had thrown open the gates of Olympic competition, in one event at least, and though other women also proved victorious, her hard-won victories remained the most distinguished.

Surely the shades of Pelops and Hippodameia would have been watching intently. Certainly, her feat was amazing, for even in Sparta, a shrine was erected to her. Pausanias describes it:

At Plane-tree Grove there is also a hero-shrine of Cynisca, daughter of Archidamus king of the Spartans. She was the first woman to breed horses, and the first to win a chariot race at Olympia.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece 3.15.1)

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post about Kyniska of Sparta, the heroine of Heart of Fire. I have certainly enjoyed writing about her, and even though the sources about her a few and far between, her legacy exploded onto the pages of my story.