Welcome back to The World of Isle of the Blessed, the blog series in which we take a look at the research, history and archaeology that went into the latest novel in the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series.

In Part I, we looked at the hillfort of South Cadbury Castle which is one of the major settings of the book. If you missed that post, you can read it HERE.

In Part II, we’re going to be taking a look at another place that plays an important role in Isle of the Blessed: Roman Lindinis.

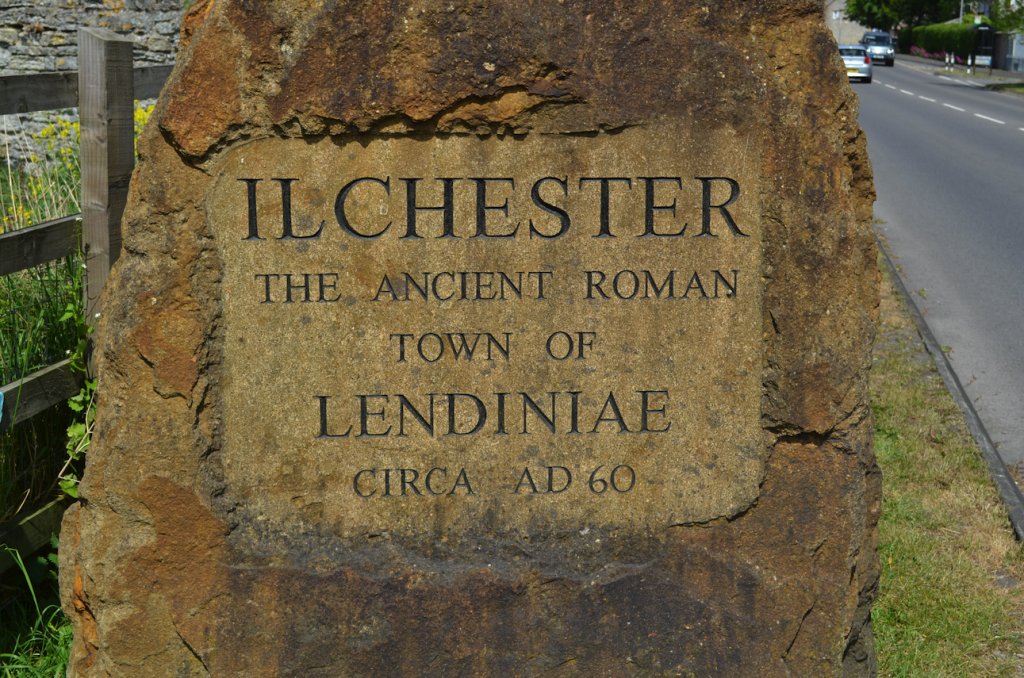

The settlement of Lindinis (also known as ‘Lendiniae’), as it is known in the seventh century Ravenna Cosmography (a list of place names from India to Ireland) is actually modern Ilchester, in Somerset, England.

Lindinis, as it was known during the Roman period, was located just a few miles from South Cadbury Castle, and Glastonbury, Somerset. This fifty acre settlement lies where the Dorchester road interests with the Fosse Way, one of the major roads of Roman Britain.

During the Roman period, Somerset was an agriculturally rich area of the Empire, with many villa estates, such as that of Pitney (which also features in the story). These estates’ primary business was in crops such as spelt wheat, oats, barley and rye. The also raised livestock, mainly cattle, but also sheep, horses, goats, and pigs.

These Roman villa owners were wealthy, and Lindinis was one of the main markets where they brought their crops and livestock.

Lindinis was not always a Roman settlement, however.

It was originally a Celtic oppidum, a native center that consisted of a large enclosure with homes, food stores and livestock. One imagines Celtic Somerset as a place of peace and vitality.

But, in A.D. 43 the Romans arrived with the advent of the Claudian invasion of Britain. Forty-five thousand troops marched over the land, including four legions, and the native Britons fought, and lost. Vespasian, the future emperor, stormed the southern hillforts of Britain, including South Cadbury Castle, ushering in an age of Roman domination.

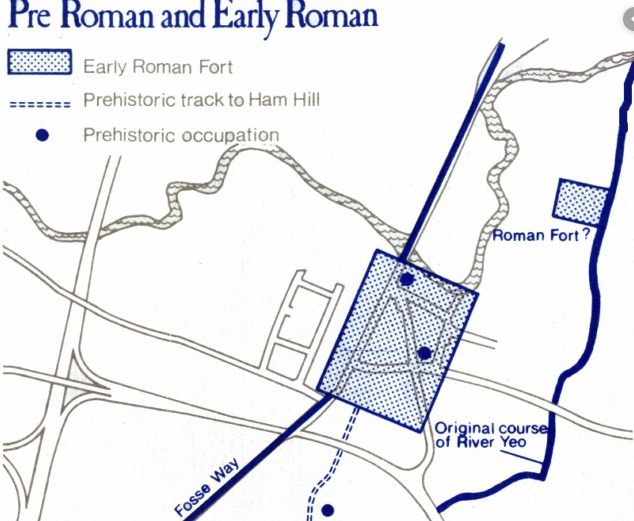

Eventually, at Lindinis, two successive forts were built on the site to the south of the river: one from Nero’s reign, and another during the Flavian period. There is also evidence for a third fort to the northeast of the river crossing where a double ditch enclosure has been discovered.

The Roman invasion of Britain was a violent time, and that violence carried on through the Boudiccan revolt of A.D. 59. But when the blood stopped flowing, an age of Pax Romana settled on the southwest of Britannia, and Lindinis was at the heart of it.

Lindinis, however, was not the main settlement of Roman Somerset. To maintain peace and order, and keep the economy running, the Romans instituted various civitates, centres of local government in which tribal groups of the region participated.

The council of a civitas was known as an ordo, and the members of the ordo were decurions, overseen by an executive, elected curia of two men. The ordo of a civitas usually included Romans, tribal aristocrats or local chieftains, and it was their job to administer local justice, put on public shows, see to religious taxation, the census, and represent the civitas in Londinium. Supreme authority, however, belonged to the Provincial Governor who was aided by a procurator, the ‘tax man’.

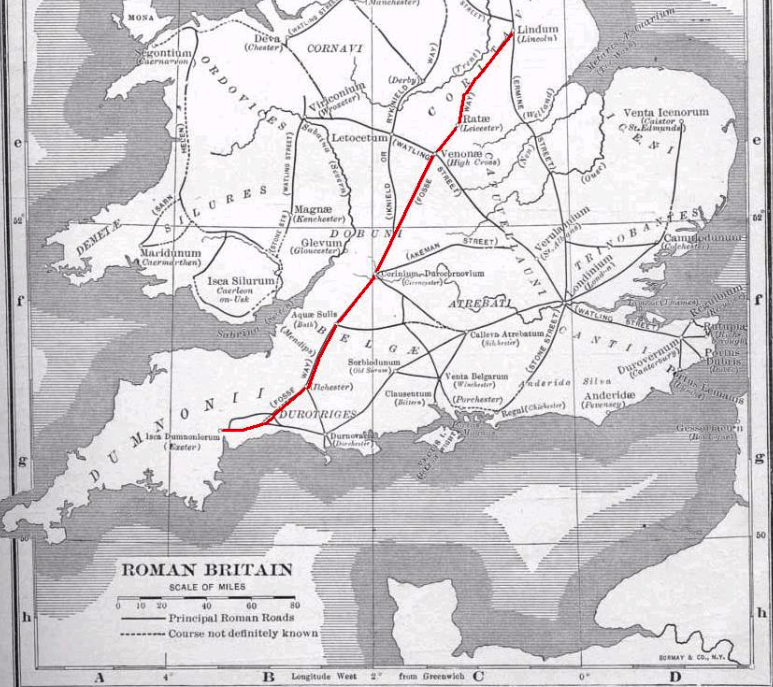

There were three major civitates during the Roman period in southwestern Britannia: Durnovaria (modern Dorchester) the civitas of the Durotriges tribe, Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter) the civitas of the Dumnonii, and to the north Corinium Dobunnorum (modern Cirencester) the tribal centre of the Dobunni.

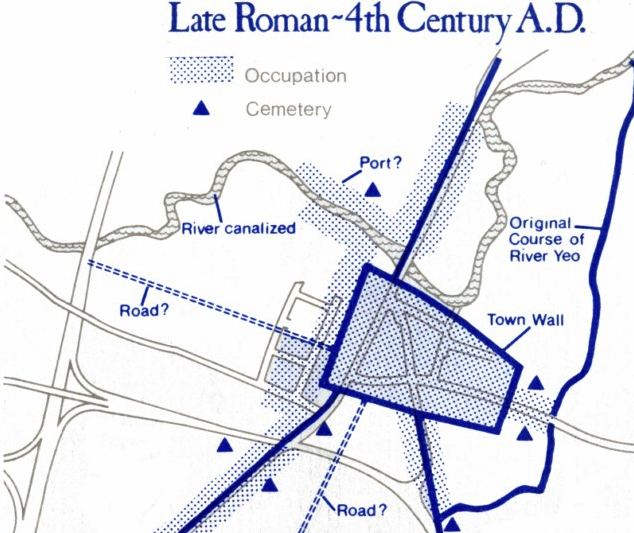

Despite its large market and location at a crossroads along the artery of the Fosse Way over the river Yoe – in the southwest, the Fosse Way ran from Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter) to Aquae Sulis (modern Bath) – Lindinis was not one of the major civitates of the region, though it did rival nearby Durnovaria.

In addition to a thriving market where wine, oil, clothing, ornaments, jewellery, tools, pottery and glass were sold, Lindinis also had gravel and stone streets, and stone walls (later). People also came to Lindinis to pay their taxes.

Where the road diverges in Ilchester – the left to Exeter, the right to Dorchester. See the bridge over the river directly ahead.

Superb post as always Adam. Love all the pictures most of where I have been when with the Re-enactors. I just love the Roman period even if sometimes it’s gruesome.

Thank you, Rita. Yes, Roman history can be extremely gruesome, but also so very exciting! And I think during the Pax Romana, they had it pretty good in Lindinis and the surrounding area. Thank you as always for your comment. 🙂

Nice article, but the captions for the photos need to have River Yoe changed to River Yeo 🙂 There used to be a small Roman museum in Ilchester, but I haven’t been for a while.

Thank you for your comment, Mike. The typo has been fixed 😉 Glad you liked the article. Cheers!

Hi

Very interesting article and I will certainly catch up with the books. I am an enthusiast for the first century Romano-Celtic period.

Can you tell me whether the town was more likely to have been referred to as Lendiniae in the Flavian period? The name Lindinis seems to appear in later periods.

Secondly, although there appears not to have been a forum or basilica, where would the ordo have met and done its business? Would they, for instance, have met at the house of a local aristocrat or home of a member of the curia?

Thanks