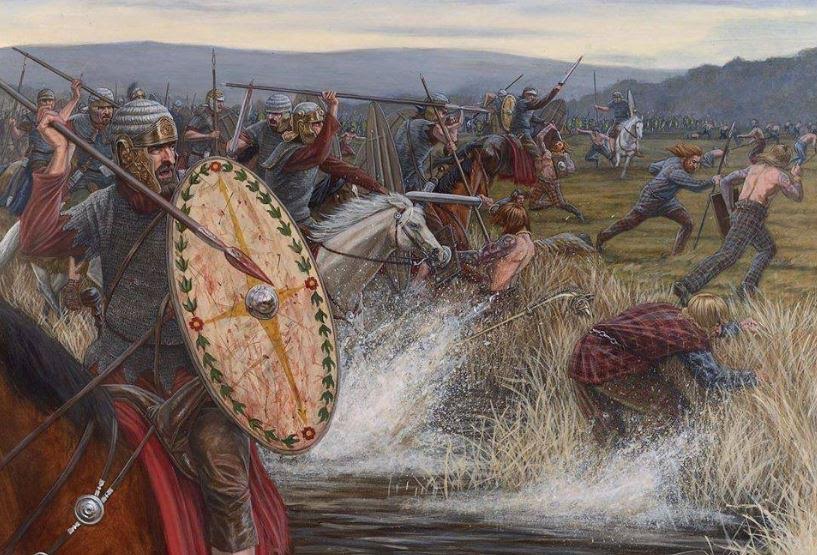

Of the many peoples conquered by Rome throughout history, few conjure such wild and barbaric images as the Dacians.

Perhaps it was because they gave Rome such a hard time of it on the other side of the Danube frontier, or crossed over to harass the Romans? Was it their vicious ways in battle or their barbaric appearance? It’s hard to tell, for as we know, history is written by the victors.

And in this fight, Rome was indeed the victor.

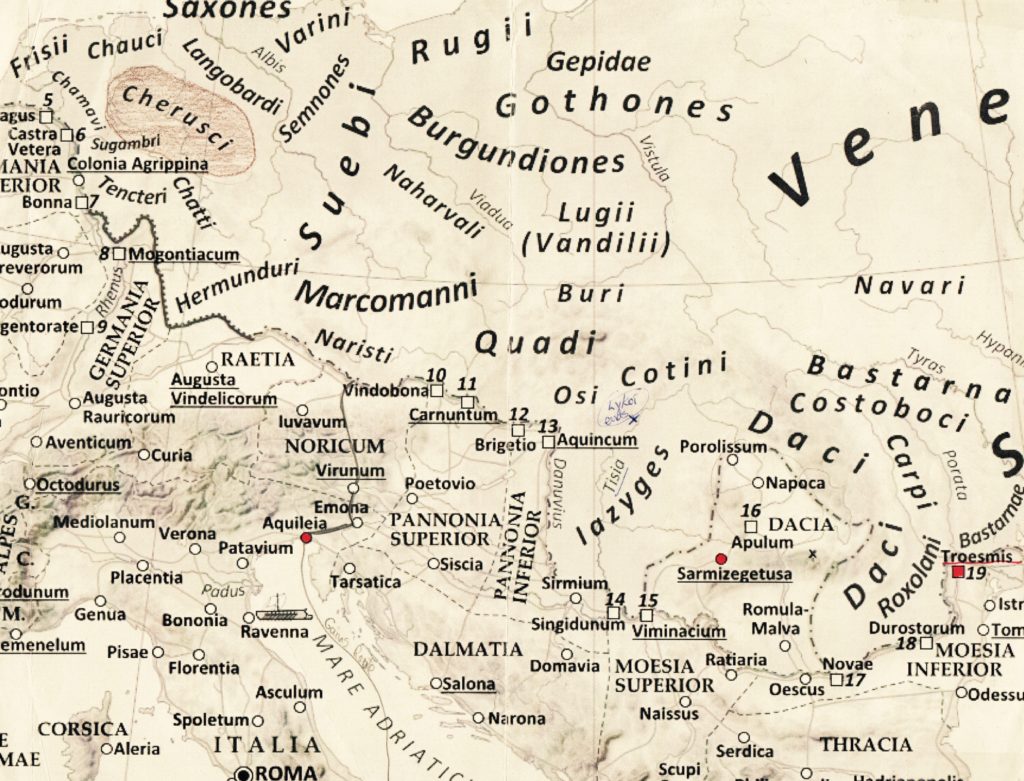

Roman Dacia (Wikimedia Commons)

In The Carpathian Interlude, the Dacians are at the heart of the story, physically and geographically.

In the story, some of our Roman protagonists end up having to go into the heart of the capital of the Dacians – a place known as Sarmizegethusa.

When I hear the name of the Dacian capital, I hear the sounds of bloody battle with Rome pounding on her gates.

Sarmizegethusa…

But before we explore this magnificent fortress/capital of the Dacians, we should look briefly at who the Dacians actually were.

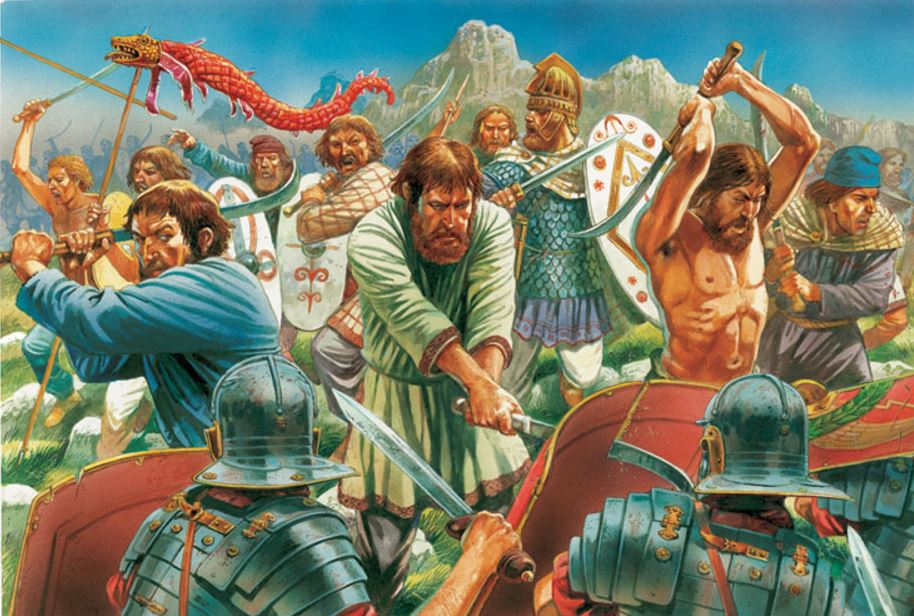

Rome vs. Dacia

The Dacians, also known as the ‘Getae’ by the ancient Greeks, were an Indo-European people inhabiting the region of – you guessed it! – the Carpathian Mountains.

They were related to the Thracians, and it has been suggested that the name ‘Dacian’ actually means ‘wolf’. This is a reference to early rituals ascribed to the Dacians in which youths had to act like wolves for a period of time.

This ritual has in turn tied the Dacians to tales of lycanthropy, or the legendary werewolves of the Carpathian region in which a large part of our story is set.

Dacian man – statue from 2nd century A.D.

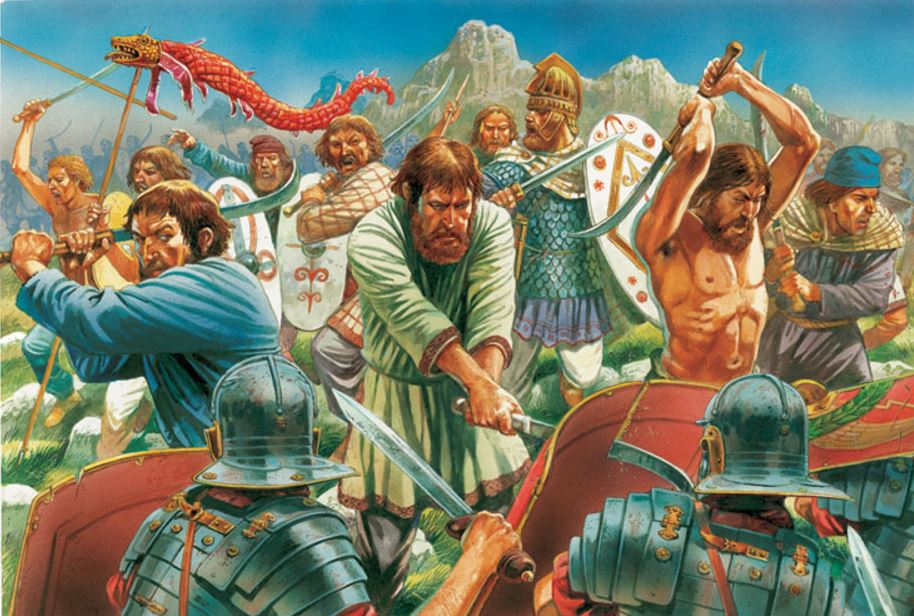

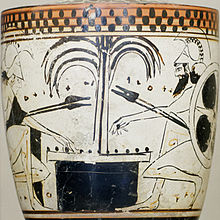

The Dacians, or ‘Getae’, were a warlike people who fought the Persians, as well as Alexander the Great in 335 B.C. on the banks of the lower Danube. Their kingdom covered a vast, mountainous area dotted with gold mines, forests and fertile fields and valleys.

It’s also said that Julius Caesar contemplated a campaign against the Dacians because of the threat they posed, but it’s the Emperor Trajan’s (reigned A.D. 97-117) campaigns against the Dacians that are really remembered.

Trajan invaded Dacia in two wars from A.D. 101-102, and 105-106.

After the first war, a treaty was struck, but both sides seemed to know it was temporary.

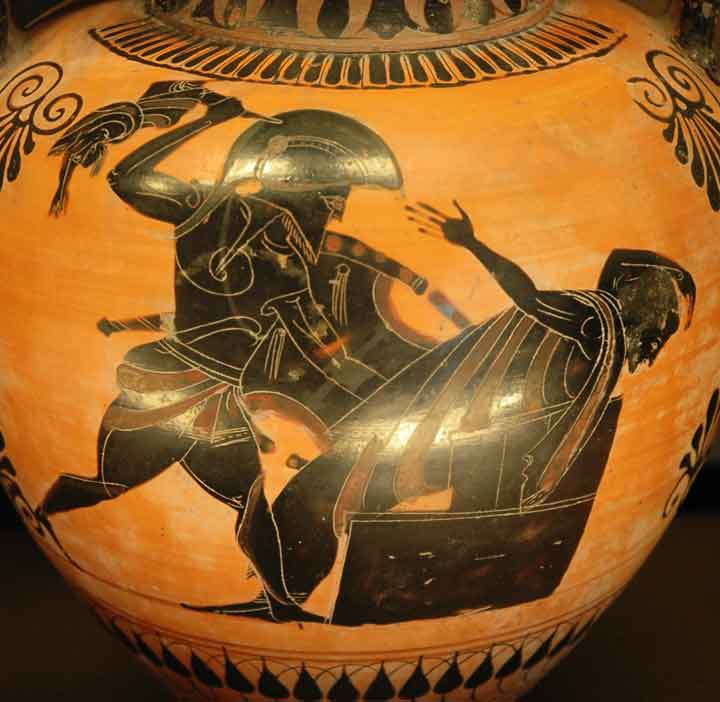

The second war was the Roman siege of Sarmizegethusa itself, and the subsequent death of King Decebalus who, being pursued by the Roman cavalry, committed suicide rather than be paraded through the streets of Rome in Trajan’s triumph.

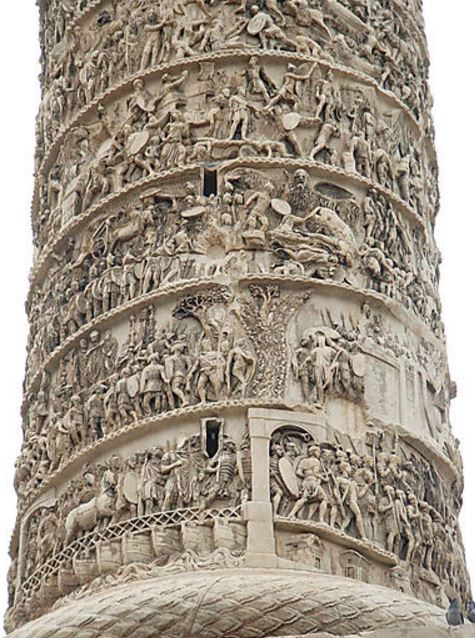

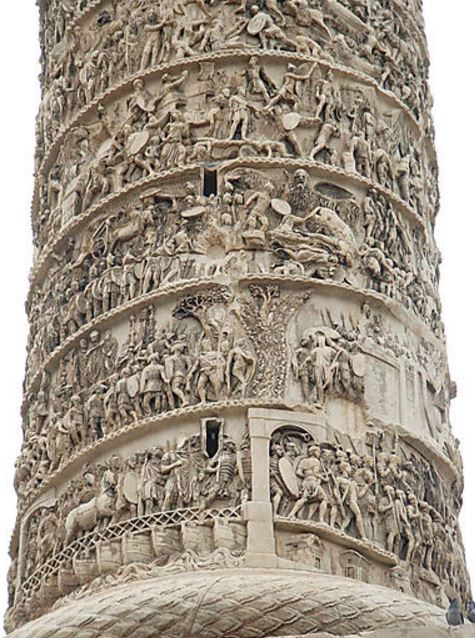

The war and the death of King Decebalus are immortalized on the monument we know today as ‘Trajan’s Column’.

Trajan’s column detail

The Carpathian Interlude, however, takes place long before Trajan’s final defeat of the Dacian people. It takes place during the reign of Emperor Augustus, when Sarmizegethusa was not yet a word on the lips of the average Roman.

Sarmizegethusa, in present-day Romania, became the capital of the Dacian kingdom under King Burebista (82-44 B.C.), and reached its peak as a rich and vibrant capital city during the reign of its last king, Decebalus.

This capital was the military, religious, and political capital of Dacia, the beating heart of the kingdom.

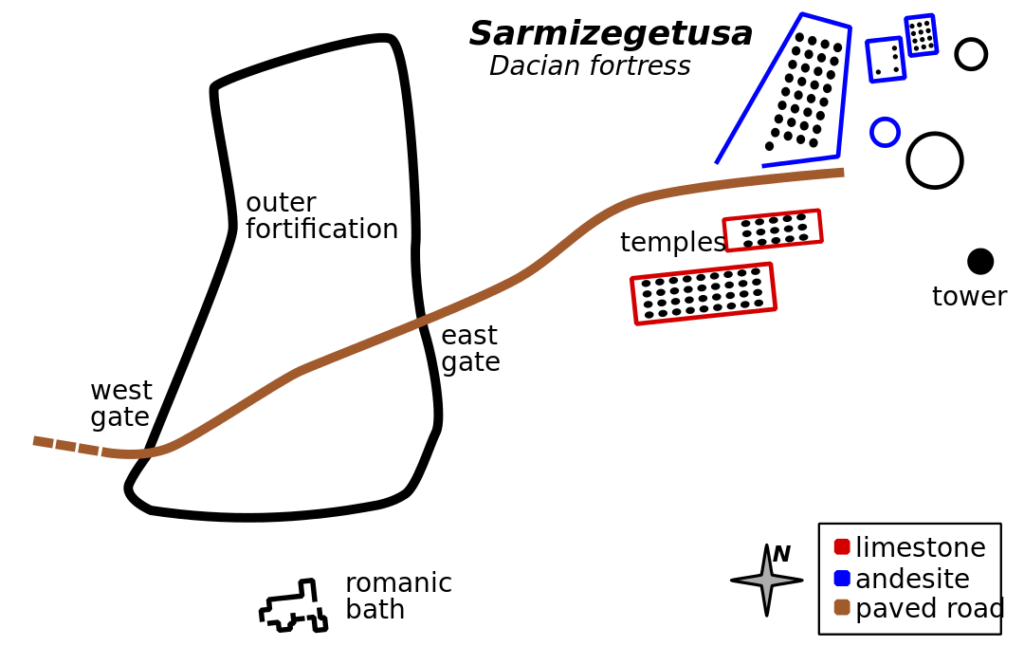

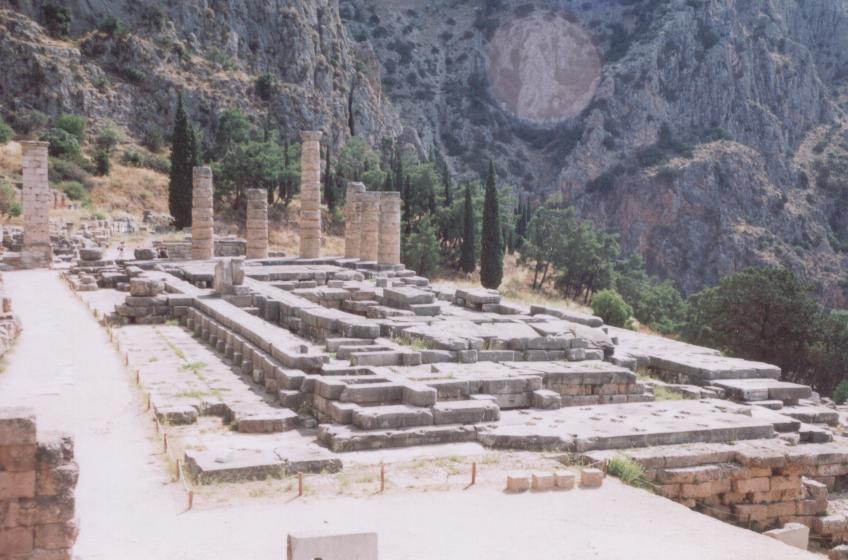

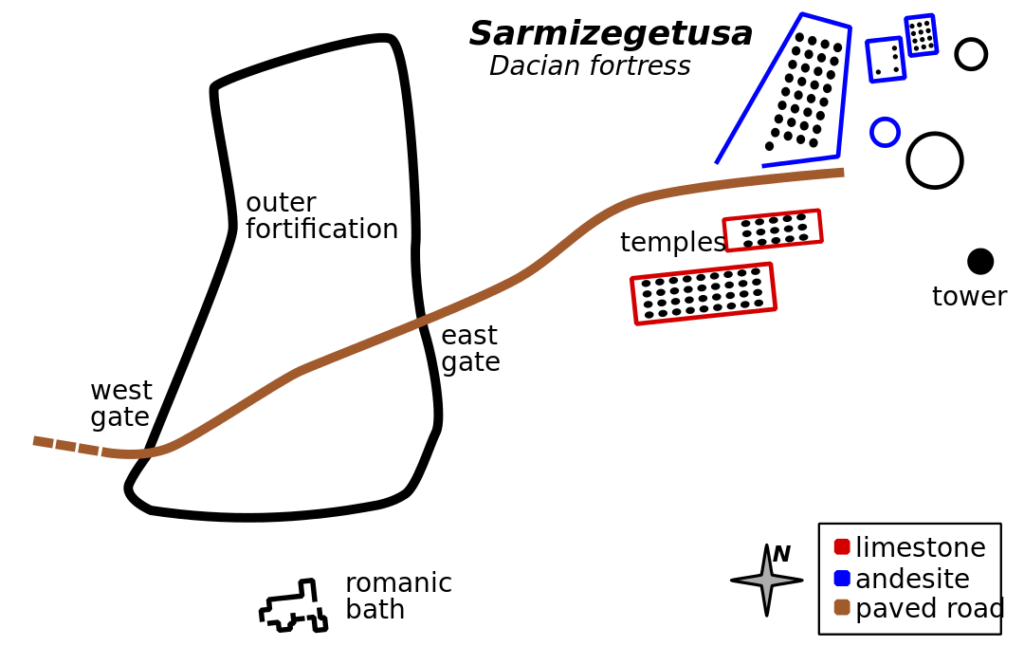

Plan of Sarmizegethusa

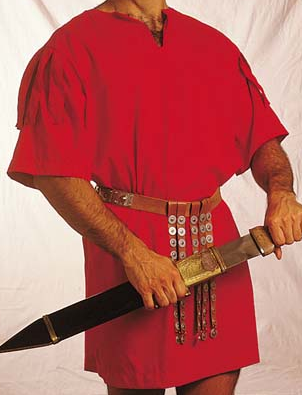

Sarmizegethusa was located on a 1200 meter high mountain and consisted of a fortress with six different citadels with a river below. Apart from the defensive network encompassing the citadels, there were also residential quarters on the terraces of the mountain below the citadels, a large sacred quarter with several temples to the Dacian gods, and workshops, including smithies, indicating metalworking skills. Some of the finds from the latter included tools and blades of the long curved Dacian sword known as a ‘phalax’.

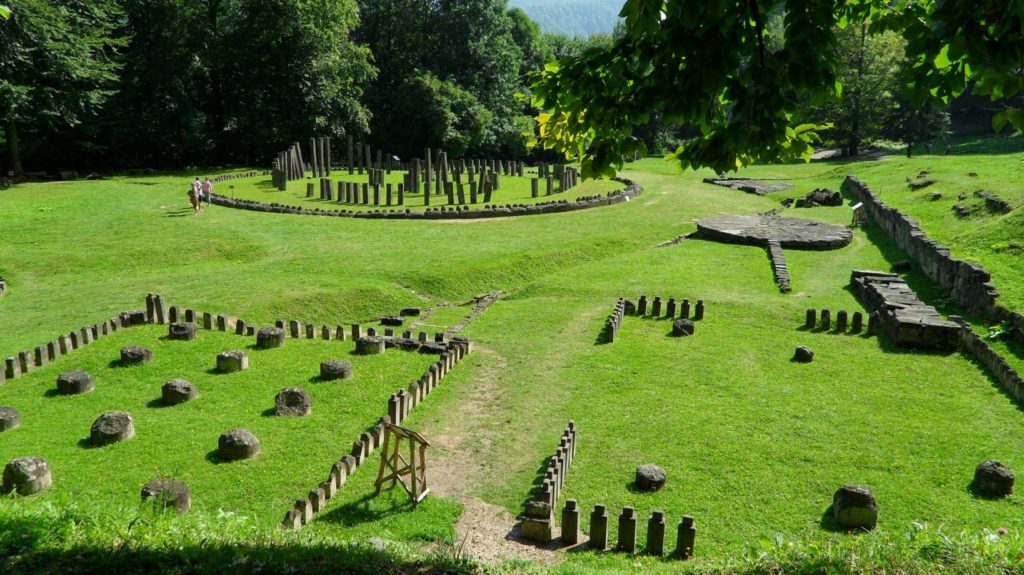

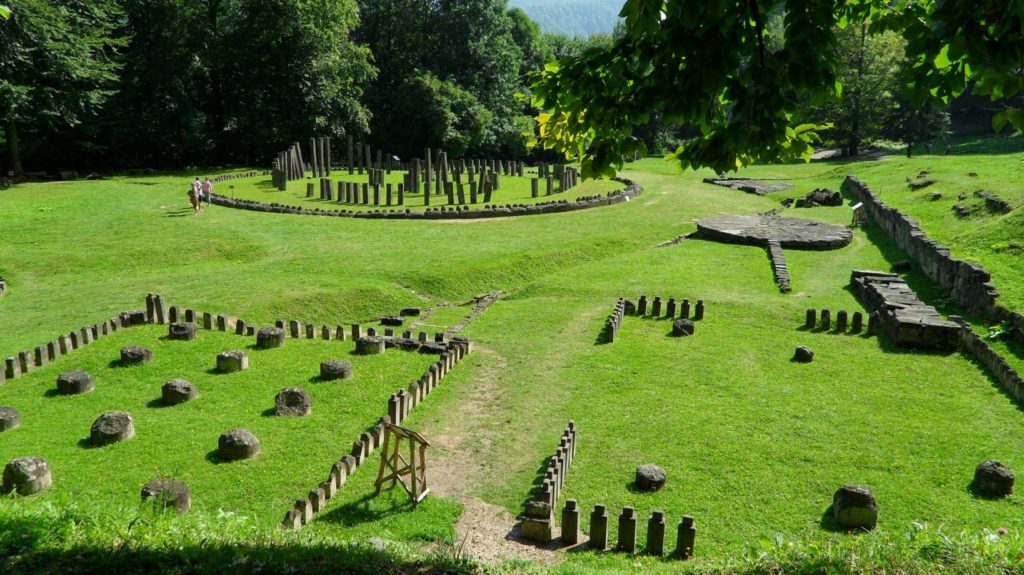

The sacred or religious zone had circular and rectangular temples, including a large sort of solar disc which some scholars believe is indicative of contact with ancient Greeks who may have influenced their religion.

Ruins of Dacian Temples in the religious quarter of Sarmizegethusa (Wikimedia Commons)

Religion was important to the Dacians, and it appears that the priest of their chief deity, Zalmoxis, played a large role in the life of the people at Sarmizegethusa. It has been suggested that the people were co-ruled by a king and a priest-king.

There were also supposedly many levels or grades of priests, just as there were levels in Mithraism.

The main gods of the Dacians, some of which are mentioned by Herodotus, were Zalmoxis (the chief god), Gebeleizis (a god of storm and lightning, sometimes equated with Zalmoxis), Bendis (the goddess of the moon and the hunt who also had a cult in Attica, Greece by order of the Oracle of Dodona), Derzelas (god of health, abundance and the Underworld), and Sabazios (a sort of horse god). The Dacians apparently also worshipped Dionysos.

Votive statue showing Bendis wearing a Dacian cap (British Museum)

Dacian beliefs were quite staunch, some of their practices no doubt barbaric to Greeks and Romans.

Herodotus explains:

Their belief in their immortality is as follows: they believe that they do not die, but that one who perishes goes to the deity Salmoxis, or Gebeleïzis, as some of them call him.

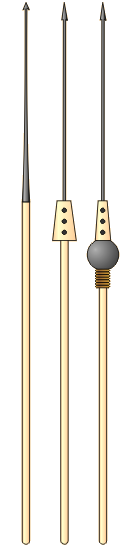

Once every five years they choose one of their people by lot and send him as a messenger to Salmoxis, with instructions to report their needs; and this is how they send him: three lances are held by designated men; others seize the messenger to Salmoxis by his hands and feet, and swing and toss him up on to the spear-points.

If he is killed by the toss, they believe that the god regards them with favor; but if he is not killed, they blame the messenger himself, considering him a bad man, and send another messenger in place of him. It is while the man still lives that they give him the message.

(Herodotus, The Histories Book IV, Chapter 94-96)

Solar Disc religious structure at Sarmizegethusa

The size of the religious sanctuary at Sarmizegethusa is substantial, their faith and practices quite old by the time of our story during the reign of Augustus.

From fact to fiction now, in The Carpathian Interlude, the Dacians have been overpowered by an evil far more ancient than their gods, one that dwells deep in the teeth of Carpathian Mountains.

When our Roman protagonists arrive in Sarmizegethusa, they must find their way to the religious quarter of the settlement and find the one man they believe can help them.

Dacian warriors from Trajan’s Column

If you do go, you may wish to go during the day when the sounds of slaughter from Trajan’s siege are muted by sunlight on the trees.

If you decide to go in the evening, or at night, be cautious, for you will be headed for a place of strange gods and of men who became wolves.

You never know what lurks in the dark of the Carpathian Mountains.

Thank you for reading.

Walls of Sarmizegethusa (Wikimedia Commons)