As some of you may know, I find Roman religion utterly fascinating. I find the customizable nature of Roman religious beliefs very interesting in that people were not bound to a particular god or goddess. Indeed, there was a different god or goddess for almost every aspect of life, and as Rome conquered new lands, new deities and traditions were added into the mix.

In some ways, Roman religion was as diverse as Roman society.

In the last blog post, we took a look at the various types of spirits, or numina, that existed in Roman religion. If you missed that post, you can read it by CLICKING HERE.

We know that there were many kinds of spirits, and various gods and goddesses that were worshiped by Romans, but what form did that worship take? Were there different ways of honouring and conversing with the gods?

In this post, we’re going to be taking a look at the various religious rites in Roman religion.

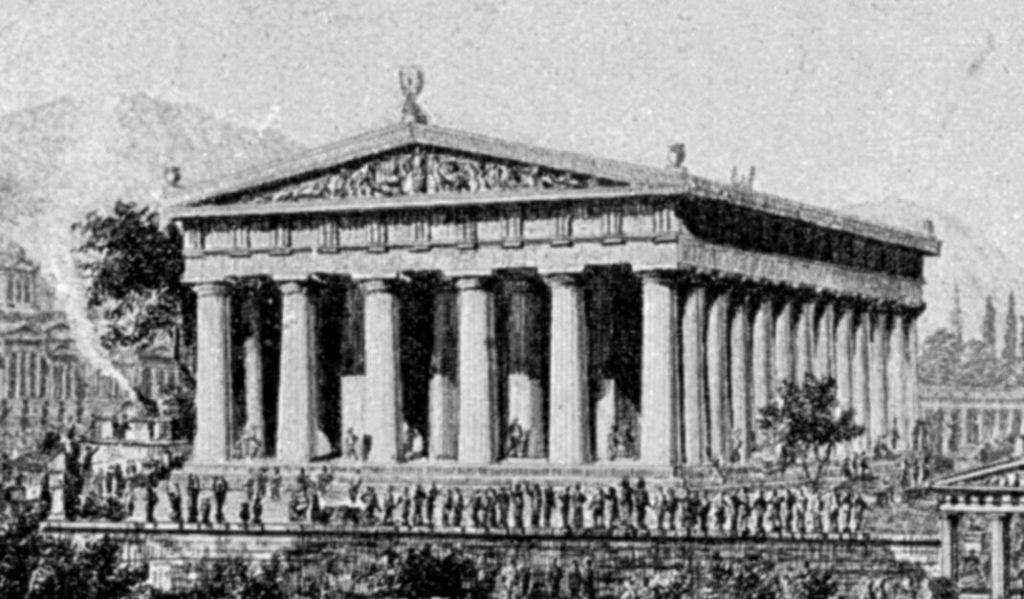

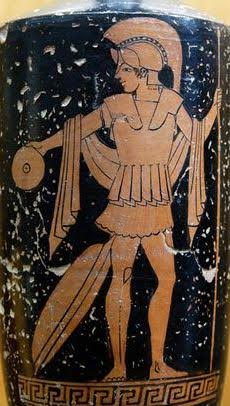

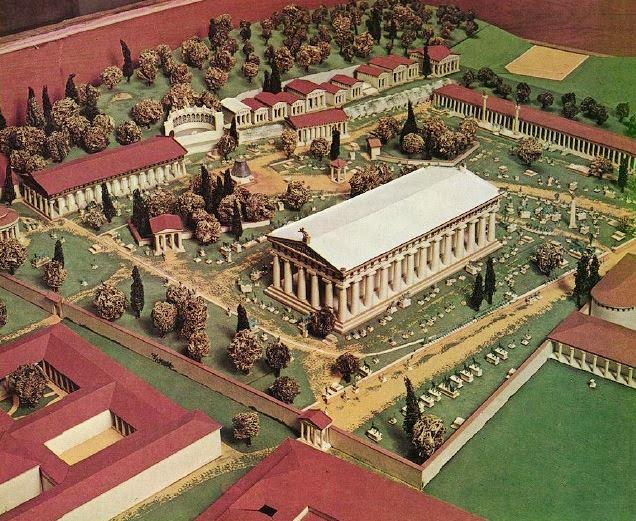

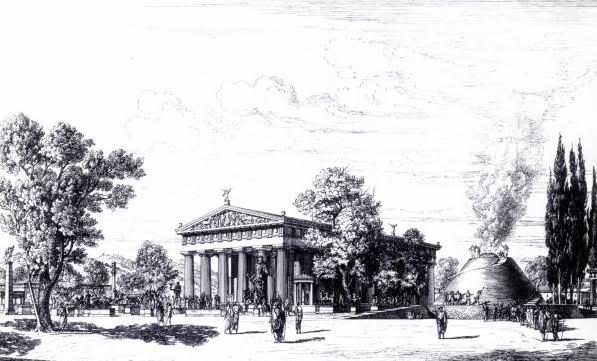

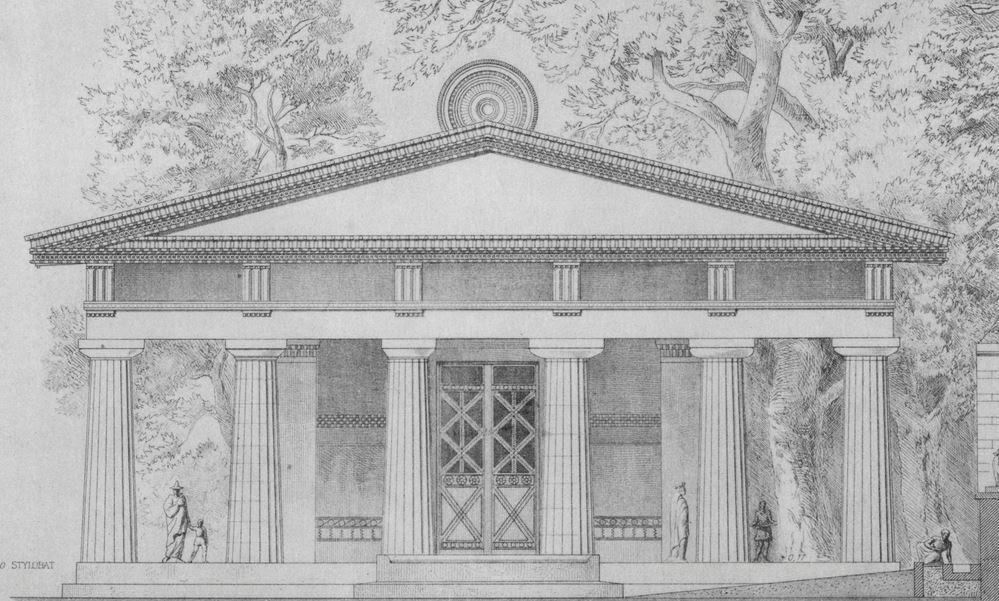

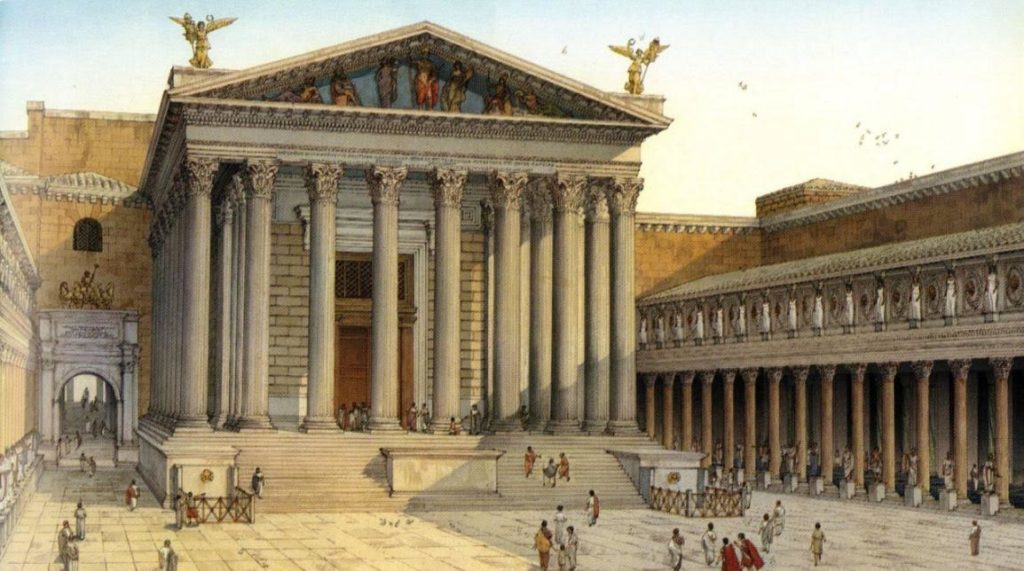

Artist impression of temple of Mars Ultor (the ‘Avenger’)

Roman religion itself was more cult-based. It involved the worship of a god, goddess or hero with specific rituals that were observed in order to win the gods’ favour.

This was more of a symbiont relationship, as it was believed that not only did mortals need the gods, but also that the gods needed mortal acknowledgment.

As mostly spirits of natural forces (ex. lighting, or the sea), the gods needed to be propitiated, kept friendly toward their mortal worshippers. This was done more through observing the proper rites than through piety or good behaviour.

The cult ceremonies performed by mortals to honour gods, goddesses, or heroes were a sort of ‘contract’ between mortal and immortal.

Let’s take a brief look at the various types of religious rites or ceremonies that were carried out by ancient Romans.

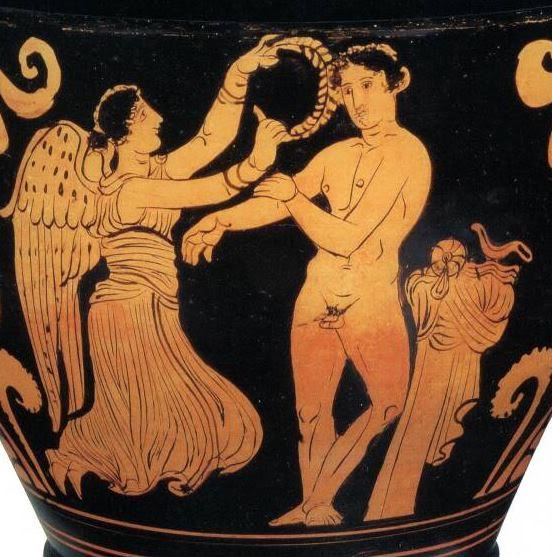

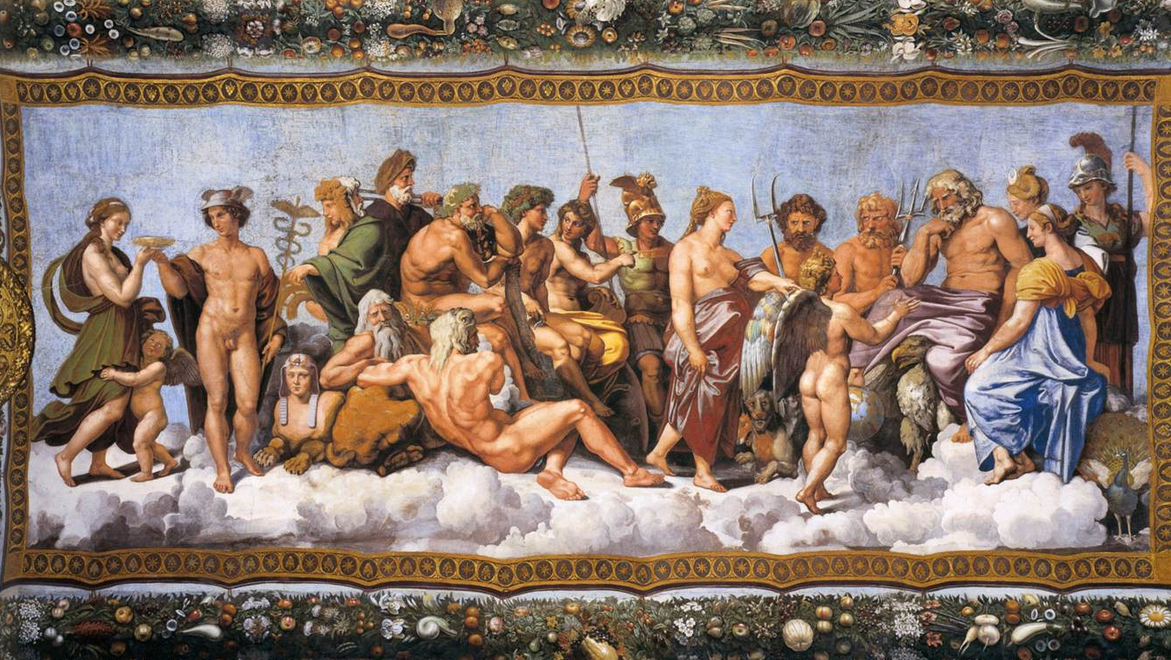

The Council of the Gods by Raphael, c.1517, Villa Farnesina, Rome

The first type of rite is one that is common to all religions, and that is prayer.

Prayers in ancient Roman religion did not always have a set text that had to be spoken, such as the Lord’s Prayer or a Hail Mary in Christianity. A Roman prayer really depended on the person offering it, and what that person needed.

As part of prayers, a worshipper offered to give something to the god, or to do something for the god (ex. build an altar). This was done with no expectation. It was a gift.

Prayers tried to cover eventualities.

A sacrifice portrayed on a lararium, or family shrine, in Pompeii

Vows were similar to prayers in that the worshipper offered to do or give something to a god, but in this instance, it was only in return for something from the immortal.

Not only did individuals make vows, but the state could also make a vow, such as if the gods helped to avert a crisis or disaster. It was common for vows to be recorded on votive tablets and left in temples as a record of the vow. With vows, there was a sort of two-way accountability.

The fulfillment of a vow often involved setting up an altar, or leaving a gift at a temple or shrine.

The vow was referred to as a nuncupatio and the fulfillment as the solutio. For the particular gift that was created or offered, it was referred to as ex voto, that is ‘in fulfillment of a vow’.

Altar to Jupiter dating to 2nd–3rd century AD. – Inscription: Dedicated by L. Lollius Clarus for himself and his family (Wikiwand)

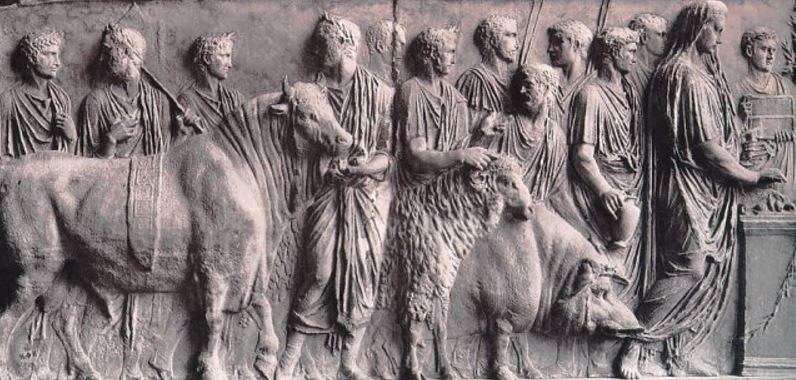

When it comes to Roman religious rites, the one that most people today probably think of is the sacrifice.

Sacrifices were a gift to the gods, heroes, and to the dead. They were carried out publicly or privately, and there were many different ways of performing them.

Sometimes, food and drink were shared between mortals and immortals at a feast. However, sometimes, in sacrifice, all the food was burned on the fire for the gods. These types of sacrifices could consist of cakes, wine, incense, oil, honey and various animals (blood sacrifices).

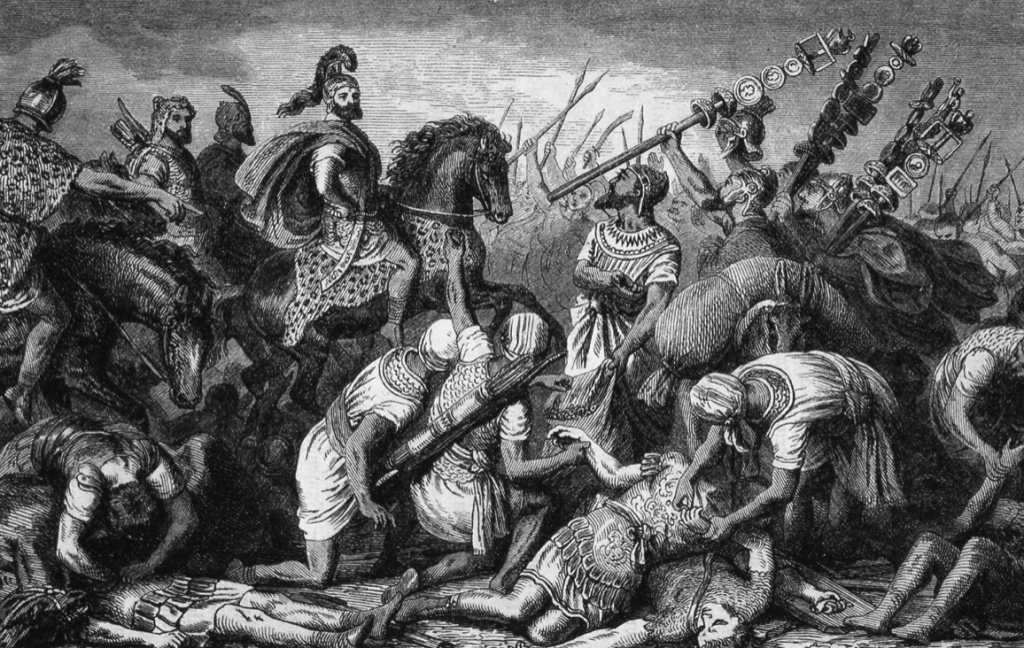

There is little evidence for human sacrifice in Roman religion except in an extreme example after the battle of Cannae (216 B.C.), when Rome experienced one of her worst military defeats ever during the second Punic War against Hannibal. The sacrifice that took place after the battle involved the burying of two Greeks and two Gauls in the forum Boarium in Rome.

There were a few categories of sacrifice in Roman religion, with various motives for each. These are evidenced mostly by inscriptions on altars. The motive could be the fulfillment of a vow (perhaps the most common), a thank offering, or the expectation of a favour from the gods. Other motives could included the result of some sort of divination, an anniversary (such as the founding of Rome on April 21), or a dedication.

Some sacrifices were considered to be instigated by the gods because of a dream or some other portent.

You can read more about the specifics of sacrifice, and how they were carried out in ancient Rome, by CLICKING HERE.

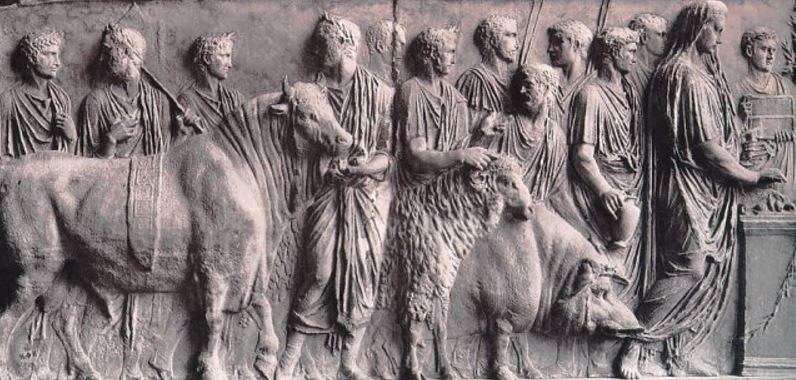

Relief of a Suovetaurilia ceremony

Another form of offering that was a part of Roman religious rites was the libation.

Libations were liquid offerings (also considered a sacrifice) to the gods that were poured on the ground. The most common was undiluted wine, but libations could also include milk, honey and even water. These were also offered to the dead at burials and later in ceremonies at the tombs of the deceased.

Another rite was the devotio. This was when a suppliant tried to gain the favour of the gods by offering their own life. This was, of course, less common.

The devotio was performed in times of desperation, such as by a general who was about to loose a battle, and so would offer his life during the battle if his forces should be victorious and avert disaster and shame. This was a ritual that was often performed for Tellus, the Earth Goddess, or the manes, the ‘spirits of the divine dead’.

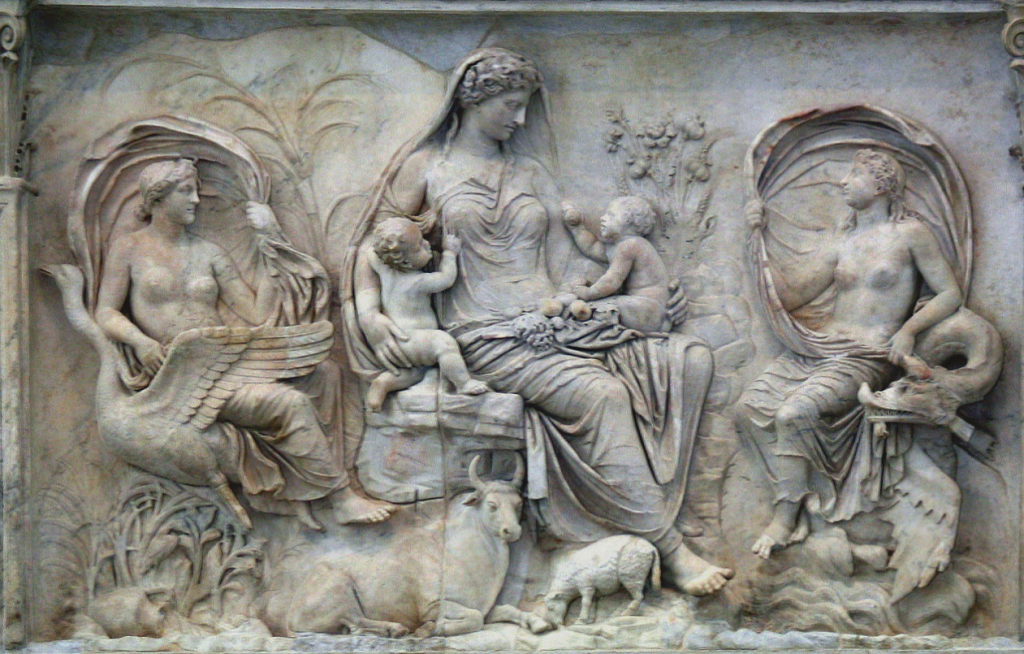

The Goddess Tellus on the Ara Pacis in Rome

The rite known as the ver sacrum was performed at a time of great crisis. This usually involved the dedication of everything born in the Spring to a god, often to Jupiter himself.

As part of the ver sacrum, all such animals were sacrificed, but children born in the Spring were expelled from the country at the age of twenty to form a new community elsewhere. This rite was performed in 217 B.C. during the second Punic War.

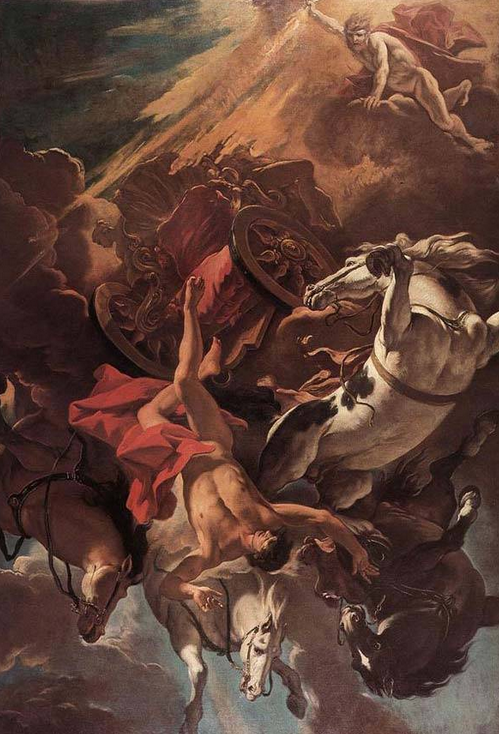

German print of Hannibal, victorious against Rome at Cannae

A lustratio was another important rite in Roman religion. It was a sort of purification ceremony to protect against evil and give good luck. It involved a procession, an animal sacrifice, prayers and other sacrifices such as of food and incense.

An example of this was when a newborn child reached nine days of age and received his or her name. In this sense, the lustratio was similar to the Christian rite of baptism.

Those of you who have read the novel, Killing the Hydra, will remember the chapter in which a lustratio ceremony takes place at the legionary fortress of Lambaesis in Numidia.

Relief of Emperor Marcus Aurelius performing a sacrifice

Divination rites were also a major part of Roman religion.

These involved the reading of signs and omens to reveal the will of the gods. It was a way of predicting the future through things such as thunder, lightning, bird signs and other phenomena.

There were two types of divination. The first was natural divination which involved dream interpretation (such as when a sick person was made to sleep in the temple of Asclepius), or oracular prophecy by someone possessed by a god. In natural divination, the gods spoke directly to mortals.

Artificial divination, however, was based on the observance of plants and animals. It could involve augury, which was the art of reading bird signs, reading the entrails of a sacrifice, or even reading the throwing of dice or drawing of lots.

Specialized training was required to carry out these rites of divination, much of which was handed down by the Etruscans to the Romans.

Etruscan bronze liver that may have served as an instructional model for a haruspex (Wikimedia Commons)

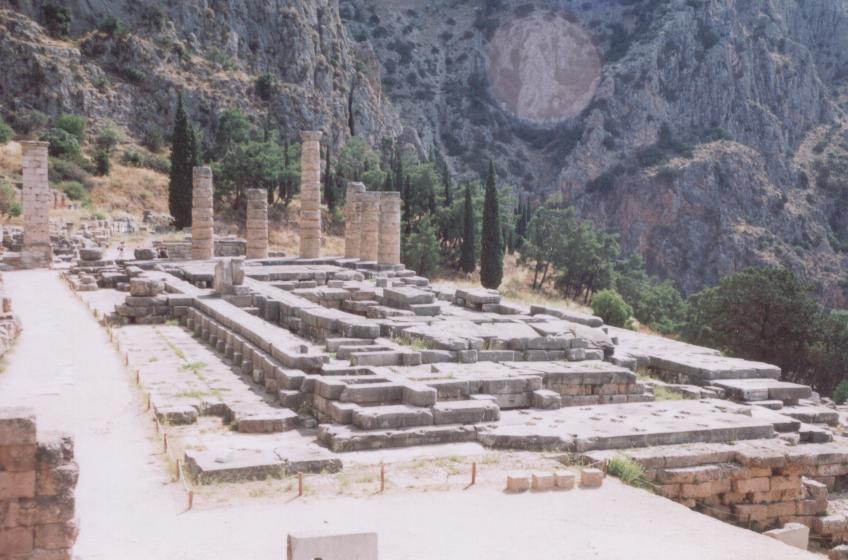

Oracles were an important part form of natural divination, and though they were more popular in the world of ancient Greece, they did play a role in Roman religion.

The most famous oracles were the Pythia at Delphi, still consulted in Roman times, and the Cumaean Sibyl (whose cave is visited in the book Children of Apollo. The god Apollo, worshipped by both the Greeks and Romans, spoke through both of these important oracles. However, there were other gods who spoke to the Romans through oracles, such as Carmentis, a water goddess who was also a prophetic goddess of protection in childbirth, and Faunus, the Roman equivalent to Pan, who was a hunter and agricultural god. In his oracular nature, Faunus spoke to mortals in dreams and through sacred groves.

The Roman state consulted oracles less frequently than, say, the ancient Athenians or Spartans. However, the prophecies of the Cumaean Sibyl that were known as the Sibylline Books, were consulted in ancient Rome. These important prophecies were destroyed in a fire that consumed the temple of Jupiter where they were kept, and so a new compendium of the Sibylline Books was transferred to the temple of Apollo on the Palatine Hill, which was built by Augustus.

Oracles were tricky though, and because they became increasingly popular among the people of Rome in the early Empire, there was a growing sense of panic. For this reason, Augustus is said to have burned two thousand books of prophecies. Perhaps the emperor had a good point? Some of you may remember the Mayan Calendar and the Y2K panic? I wonder if Nostradamus’ prophecies said anything about our current COVID crisis? And what about Voldemort and his obsession with a prophecy in the Harry Potter series!

Let’s not think about it. Oracles, it seems, were a double-edged gladius.

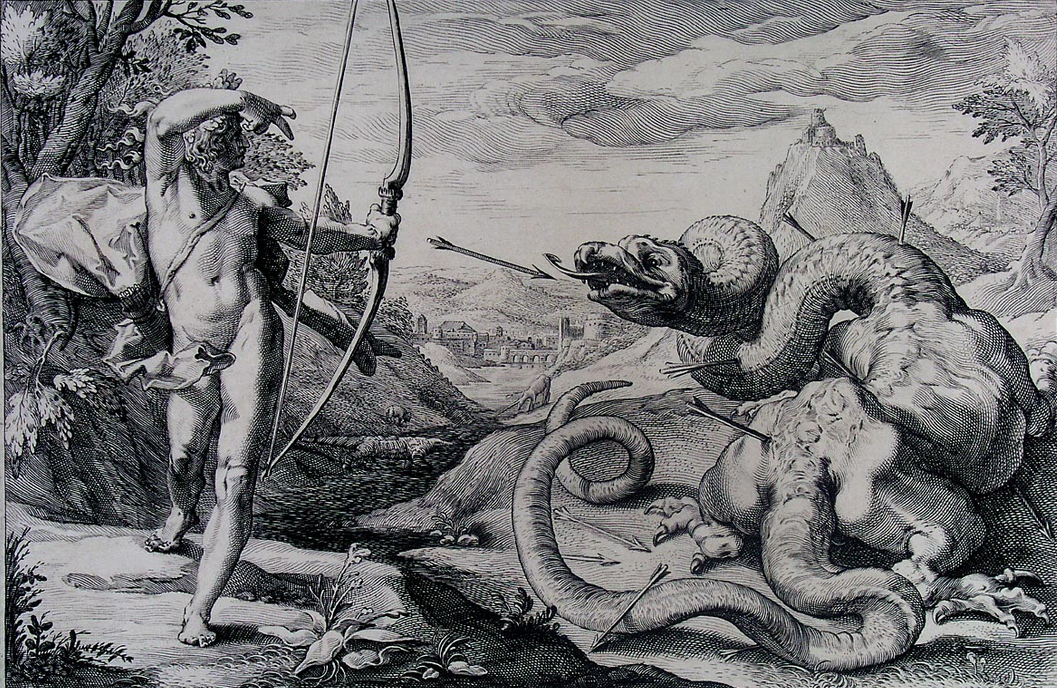

Apollo and the Pythia who uttered his prophecies to mortals

The final sort of religious rite we’re going to take a look at is one that is still popular today.

Astrology came to Rome in the second century B.C. from Babylon and Egypt. At the time, it was very popular, and it was thought to be compatible with religion because the stars foretold the future, and that that future was the gods’ will.

At first, even Christians and Jews accepted astrology and the predictability of the planets and stars.

Most famously, Emperor Septimius Severus and Empress Julia Domna were big believers in the art of astrology, and they used astrologers on a regular basis. This part of their beliefs, and how it affected their rule, is explored in the Eagles and Dragons series.

Looking to the to the stars for guidance…