Legend has it that Leto, the beautiful Titaness, travelled the world over as her belly swelled with the offspring of cloud-gathering Zeus. No town or village, forest or mountain fastness would welcome her with the great goddess Hera pursuing her to the ends of the earth. Rest upon land was forbidden to the expectant mother who fled her tormentors from the great forests of Hyperborea to the salt sea. When Leto’s time was near, an island with no roots welcomed her.

…so far roamed Leto in travail with the god who shoots afar, to see if any land would be willing to make a dwelling for her son. But they greatly trembled and feared, and none, not even the richest of them, dared receive Phoebus, until queenly Leto set foot on Delos… (Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo)

The Sacred Harbour of Delos and part of the archaeological site

There are many sacred places in the world, places that have been the centre of worship for ages. They are places where history and myth vibrate together, where they can be felt, and touched.

The Aegean island of Delos is such a place.

This post isn’t a history lesson. It’s more of a visual journey, something for your senses to enjoy.

At the eye of the group of islands known as the Cyclades, this little island was a centre of religion, inspiration, and trade for millennia. Empires went to war over control over this small place just five kilometers long and thirteen-hundred meters wide.

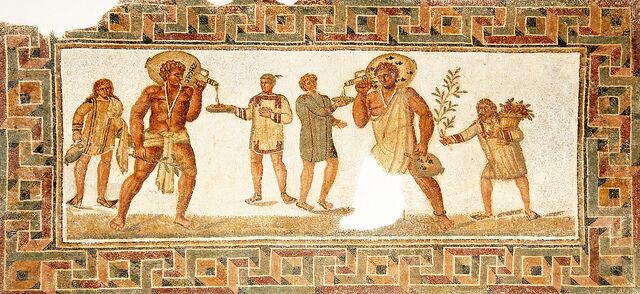

The House of the Dolphins

Delos has been occupied, as far as we know, since the third millennium B.C. As the midway point between the Greek mainland, the western Aegean islands, and the Ionian coast, it was the perfect stopping point for ship-bound traders.

However, the main reason for the popularity of Delos, for its sanctity, was that it was believed to be the birthplace of two of the most important gods of the Greek and Roman pantheons – Apollo and Artemis.

To reach Delos today you must take a boat from the nearby Cycladic island of Mykonos. It is a choppy ride and not for those without sea legs. The Cyclades are in a windy part of the Aegean. However, the short odyssey to get there is well worth it. Once you come out of the waves and into the Delos Strait between the island of Rhenea and Delos itself, the waters welcome the visitor and Delos appears like a hazy jewel in a brilliant turquoise sea.

Part of the residential district of Delos

Delos is not just another archaeological site to be seen hurriedly through the lens of a camera. For those open to it, as soon as you set your foot on the path from the ancient ‘Commercial Harbour’ to the upper town, you know this place is different. This is a place to be felt with all your senses.

Apollo’s sun beats down with intense heat, and the hot Aegean winds wrap themselves about you at every turn. The voices of the past are loud indeed, be they of priests or pilgrims, merchants or charioteers, theatre patrons or performers, the rich or poor. Everyone came to Delos for all manner of reasons, for thousands of years.

Ruins along the Sacred Way

To preserve the purity of the place in ancient times, it was forbidden for anyone to be born or to die on Delos. Those who were involved in either of these acts were sent across the strait to Rhenea to do so. As the birthplace of important gods, this was taken very seriously.

The Palm and the Sacred Lake

…the pains of birth seized Leto, and she longed to bring forth; so she cast her arms about a palm tree and kneeled on the soft meadow while the earth laughed for joy beneath. Then the child leaped forth to the light, and all the goddesses washed you purely and cleanly with sweet water, and swathed you in a white garment of fine texture, new-woven, and fastened a golden band about you. (Hymn to Delian Apollo)

The usual visitor might be led directly to the small museum on-site where several artefacts are on display. Others feel themselves pulled in the direction of the place that made Delos famous. The Sacred Lake, where Leto is said to have laboured for nine days when giving birth to Apollo and Artemis, is still there with its magnificent palm swaying in the sea breeze. The lake is drained now, and the palm is a distant ancestor of the original, but it is still a marvel to stand in a place revered for ages. On a nearby hill, the nine Delian lions stand guard over the birthplace of the gods, ever watchful.

Mount Cynthus

Delos was not just a quiet place for religious reflection. Indeed, it was very busy and at one point had a population of about 25,000 people. It was covered with sanctuaries and temples, monumental gates and colossal statues, stoas, shops, homes, theatres, stadia and agora. And above it all was mount Cynthus, 112 meters high, where the Archaic Temple of Zeus looked down over the birthplace of his son and all the mortals coming to do them homage.

If you stroll about the island you will be greeted by something new around each corner; a different view of the sea, ancient homes with some of the most beautiful mosaics ever found open to the sky, the ruins of a once-beautiful theatre, or even something as simple as a stretch of marble paving slabs from whose cracks red, purple and yellow flowers sprout to paint the scene.

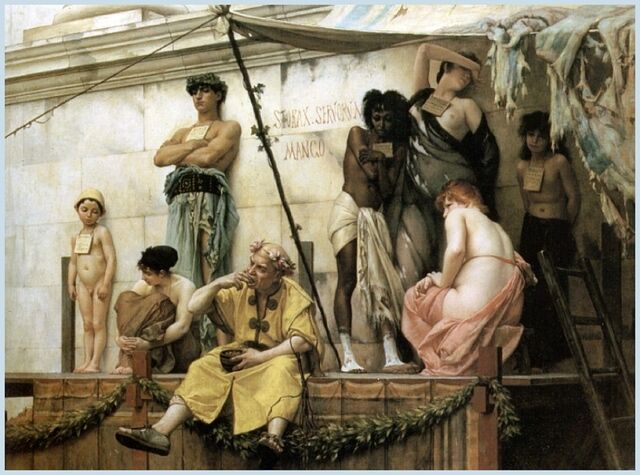

Temple of Isis in the Sanctuary of Egyptian Gods

Delos was a meeting place of many deities, not only Apollo and Artemis. There were also temples to Zeus, Athena, Poseidon, Hera and many others of the Greek Pantheon. On the Island of Delos there were also sanctuaries to Syrian, Egyptian and Phoenician deities. Near the stadium area, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of a Jewish Synagogue. All were welcome to make offerings, worship, work and trade on this tiny rock-of-an-island which, by the 1st century B.C., was one of the great commercial centres of the world.

As one walks around the site today, it is not necessarily the voices of trade and craftspeople at their daily work that one is reminded of.

The shops have long since closed their shutters and turned to dust. The treasuries have been looted, and subsequently crumbled. Grass and wild flowers sprout from between the paving slabs of the Sacred Way where asps warm themselves beneath the rays of Apollo’s light.

One of the Delian Lions overlooking the Sacred Lake

In truth, it’s difficult to describe in words the feeling one gets while cutting a meandering path among these ancient ruins. Delos is a place of light and colour and ancient beauty, an omphalos of the Aegean to which travellers have been drawn for ages.

For myself, there is an overwhelming sense of awe and absolute peace that creeps over me whenever I visit this place. It’s not always an easy task to shut out the groups of tourist hoards that descend upon this unassuming rock by the boatload. However, if you can manage the journey there, to break away from the masses, you will be treated to an experience in which you will delight in myriad shades of blue and pristine white, hot Aegean breezes and the loving light of the sun.

Most of all, you will stand still and wonder at the sight of a swaying palm, that one spot on the island where gods were said to have been born, and which earned this place called Delos renown for all time.

…queenly Leto set foot on Delos and uttered winged words and asked her… “Delos, if you would be willing to be the abode of my son “Phoebus Apollo and make him a rich temple –; for no other will touch you, as you will find: and I think you will never be rich in oxen and sheep, nor bear vintage nor yet produce plants abundantly. But if you have the temple of far-shooting Apollo, all men will bring you hecatombs and gather here, and incessant savour of rich sacrifice will always arise, and you will feed those who dwell in you from the hand of strangers…

(Hymn to Delian Apollo)

A picture is indeed worth a thousand words, so, if you would like to see more, just continue scrolling down to continue the visual Odyssey.

Thank you for reading…

The nine Delian Lions keep a timeless watch over the Sacred Lake

Part of the archeological site of Delos. Excavations continue as most of the island remains to be uncovered

Terrace of a Delian house overlooking the Commercial Harbour

Mosaic at the House of the Dolphins

Doorway to the back of the theatre

The ancient theatre of Delos. The artistic competitions of the ‘Delia’ were performed here

Island cisterns where rain water was gathered

Alleyway among the ruins of Delos

Mosaic in the residential quarter

Mosaic waves open to the sky

Statues in the House of Cleopatra

Ruins near the harbour

Remains of colossal statue of Apollo (the torso)

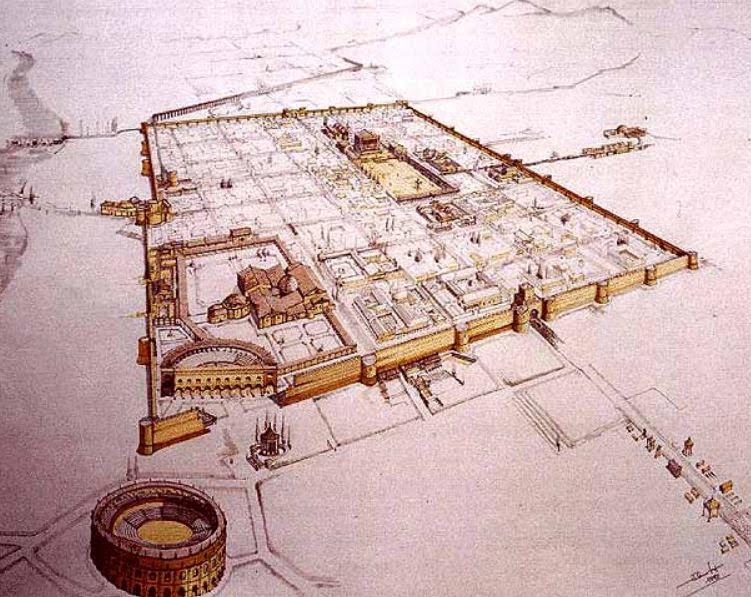

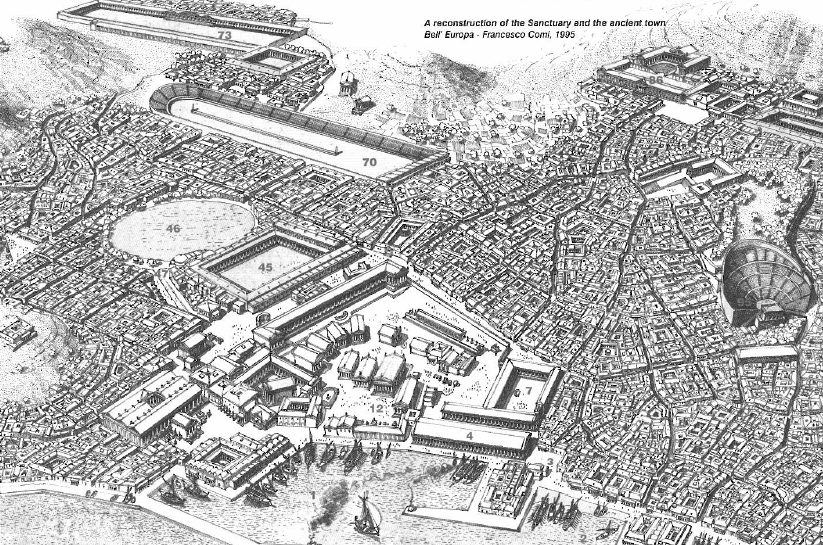

Artist rendering of ancient Delos – Francesco Comi, 1995

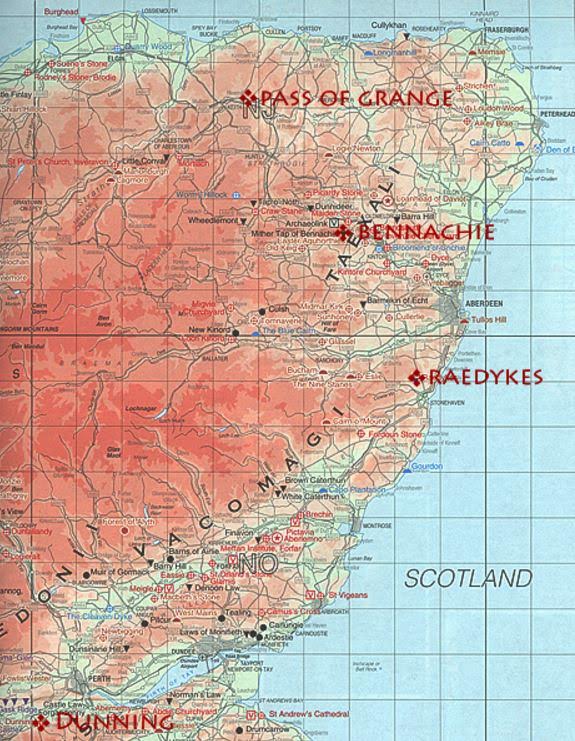

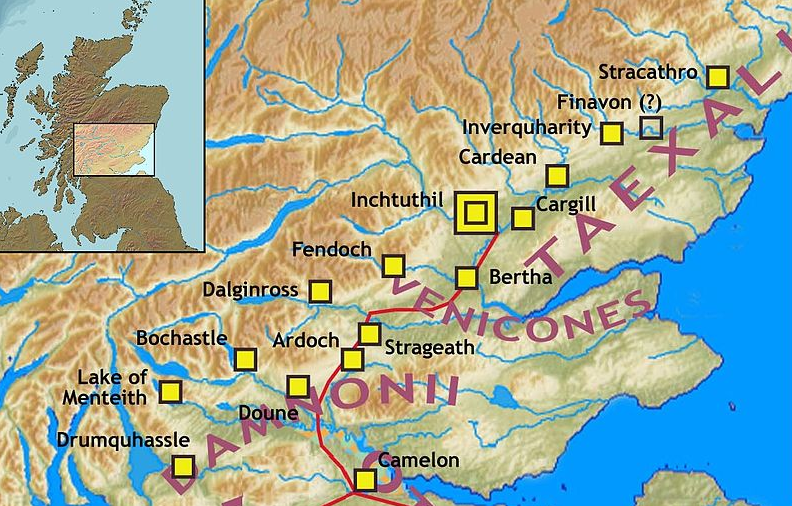

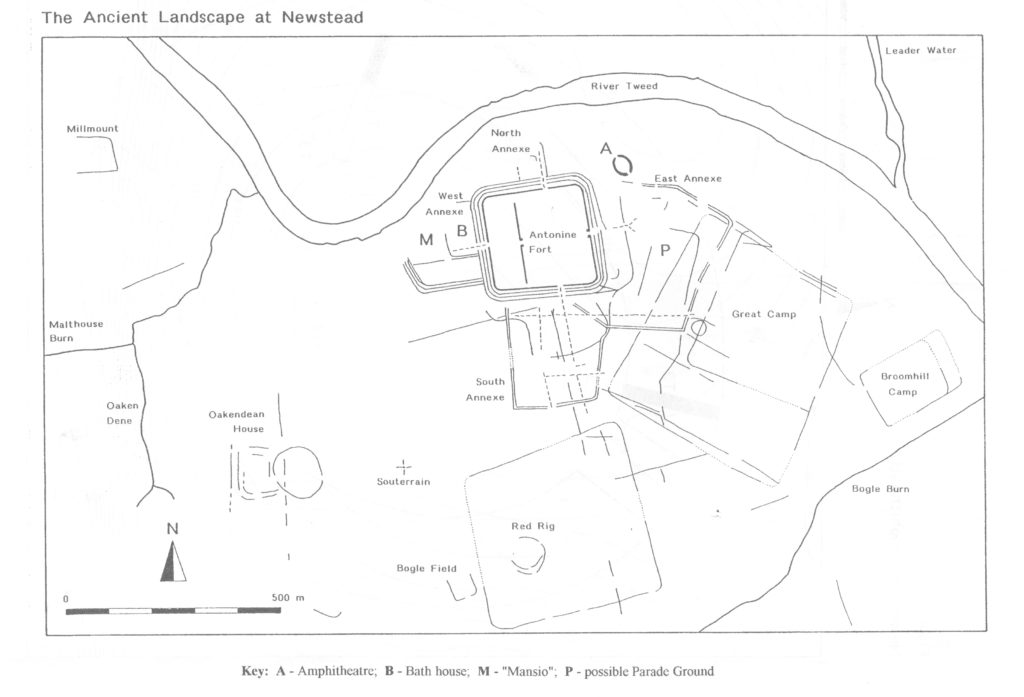

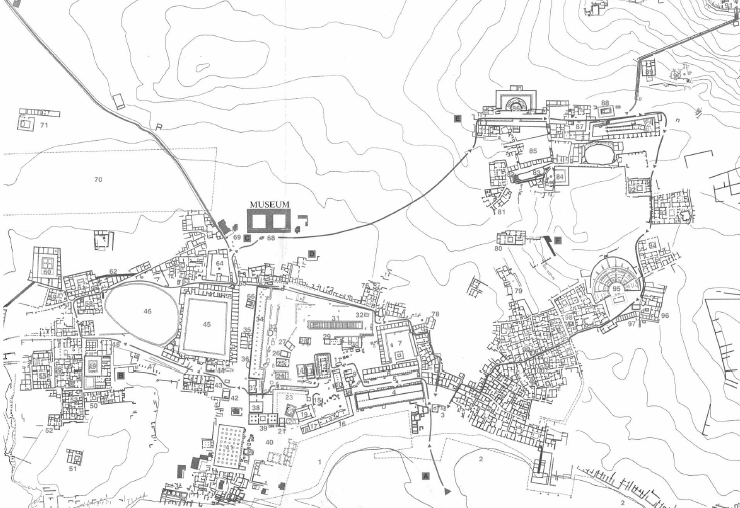

Map of the Archaeological site of Delos Edition sponsored by the Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Culture and the European Community (3rd CSF 2000-2006)

To Delos in another light, other than the parched, tourist-packed summer landscape we are familiar with, check out the beautifully shot video below, directed by Andonis Theocharis Kioukas. In this video, you see Delos in the fullness of spring, quiet, green, with myriad colours bursting from among the ruins.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8nTyppBJVso