We’re going to a different sort of place in this instalment of The World of Killing the Hydra.

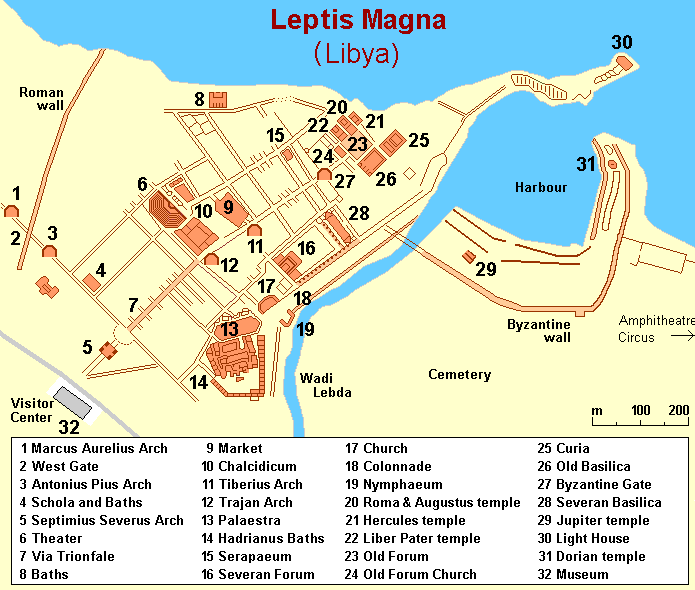

In Part I, we explored the beauty of Leptis Magna which is where the book begins, and which was also the home of Emperor Septimius Severus.

But the Roman Empire was not all about beautiful monuments, lavish banquets, and the adoration of the people for the ruler of the time.

In fact, the Roman Empire had its own maze of back streets and alleyways where life was seedier, and more visceral. It wasn’t all polished marble, but rather slick brick and stinking cells.

WARNING: This post is not suitable for readers under 18 years of age. Also, if you are easily offended, some of the pictures of Pompeian frescoes in this post might be a bit too saucy for you. Just a word of warning for the innocent-minded.

We’re going to take a very brief look today at prostitutes and brothels in the Roman Empire.

Now, if you’re suddenly hoping that Killing the Hydra is my attempt at historical erotica, well, you’re looking in the wrong place. The book is not an orgy extravaganza. If you want that, check out the film Caligula with Malcolm McDowell in the title role.

However, you can’t really write about the Roman world without touching on the long-standing role that prostitution and brothels had to play in society.

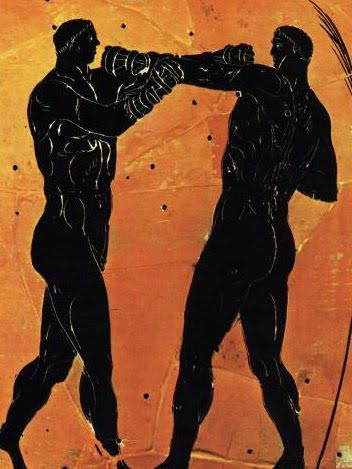

They existed, and they most certainly flourished. People of all classes, mostly men, made it a normal practice to visit their favourite brothel from time to time.

If you liked the HBO show ROME, you might have an image of Titus Pullo whoring his way through the Subura with his jug of wine in hand. Certainly, this sort of behaviour was not uncommon, especially for troops fresh back from the wars and looking for a good time.

The flip side might be the richer, upper class nobility who may have believed visiting prostitutes was fine, as long as it was done in moderation and didn’t cause a scandal.

The prostitution scene in the Empire was as large and varied as the workers and clients who kept it running. There was something for everyone!

But let’s look at things a bit more closely.

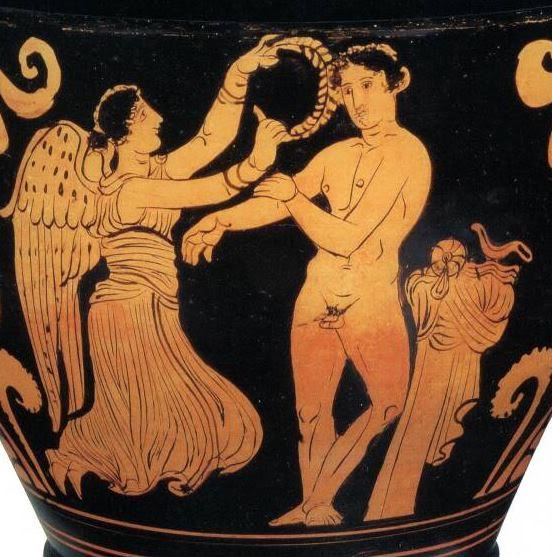

The She-Wolf, or ‘lupa’, suckling Romulus and Remus

One could say that prostitution has ties to the founding of Rome itself.

You may have read about Romulus and Remus, the brothers who founded Rome and were suckled by the She Wolf, or Lupa.

We have heard of lost children being raised by wolves before, but in the instance of Romulus and Remus, many believe that they were actually raised by a prostitute who found them on the banks of the Tiber. The slang word for prostitute in Latin was lupa.

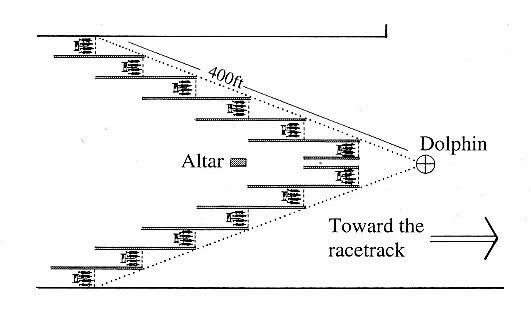

And the word for brothel was in fact lupanar or lupanarium.

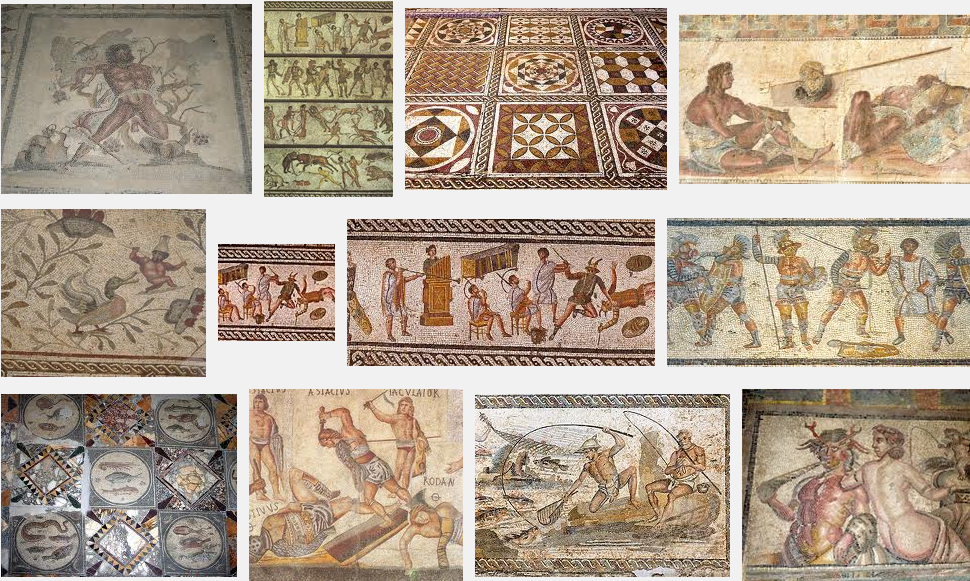

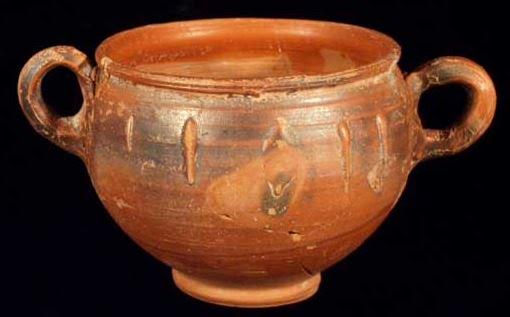

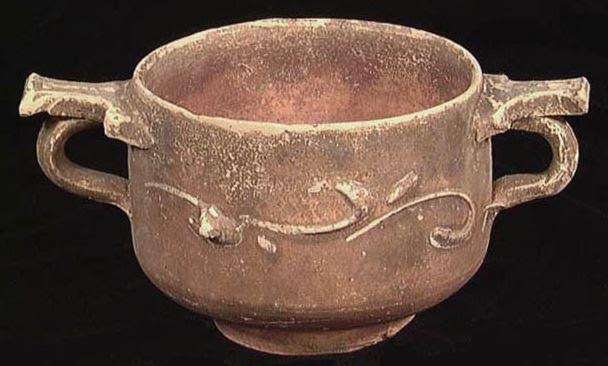

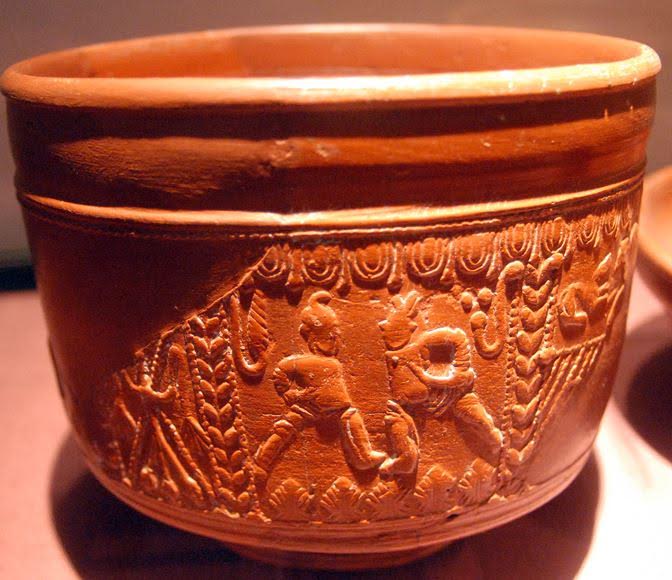

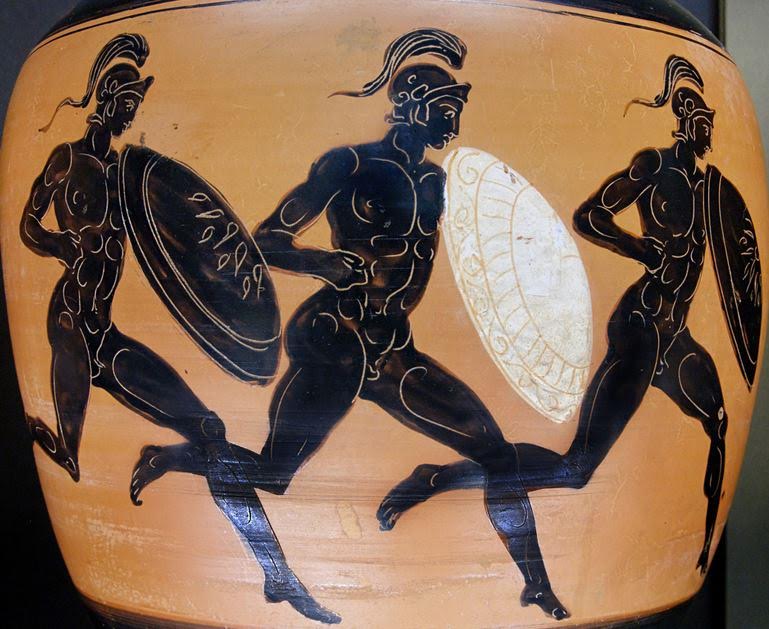

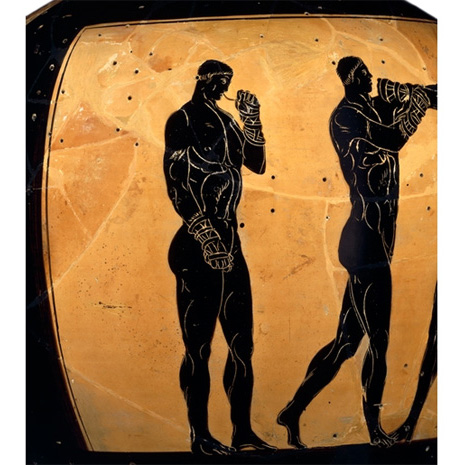

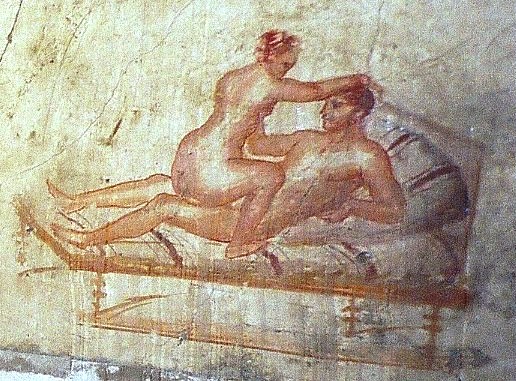

Clients were drawn in by the sexual allure of displayed ‘wares’, sometimes lined up naked on the curbside, and the various experiences to be had within. The latter were sometimes illustrated in frescoes or mosaics on the walls of the lupanar. These were intended to add to the atmosphere, or were a sort of menu of pleasures to be had.

There were of course ‘high-class’ prostitutes who catered to wealthy and powerful patrons, women who were skilled at conversation, music and poetry. These high end lupae provided an escape, or a feast with friends, in lavish surroundings coupled with a sort of blissful oblivion. Some might have been purchased by their wealthy clients to keep for themselves, and if that was the case they might have ‘enjoyed’ a relatively easy life compared to the alternative.

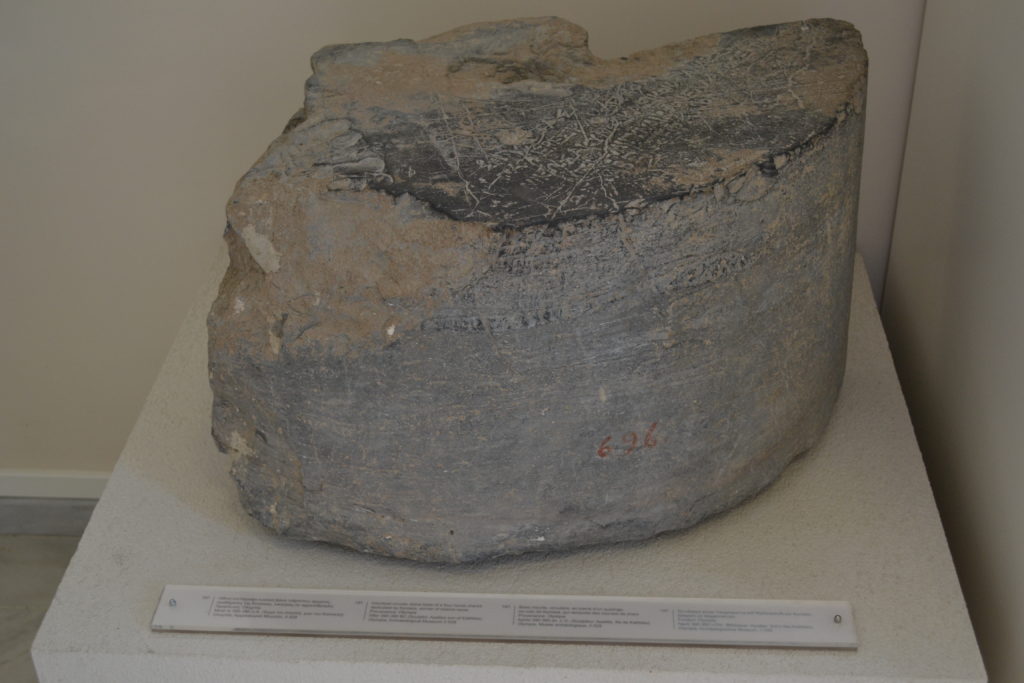

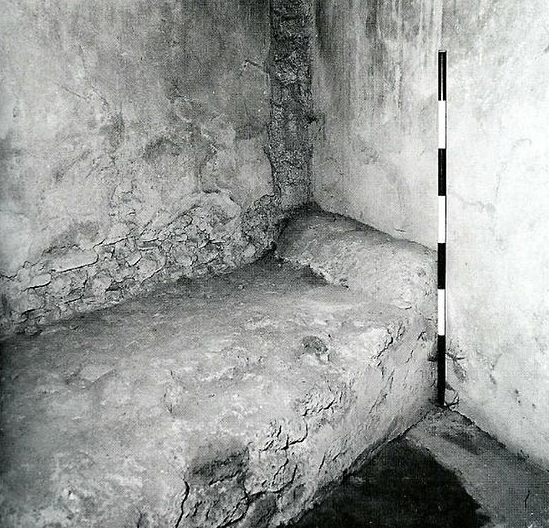

A lupa’s ‘office’ – a cement bed

The truth for most, however, was that they were slaves. And slaves in ancient Rome, as we all know, were objects, property to be used and disposed of on a whim.

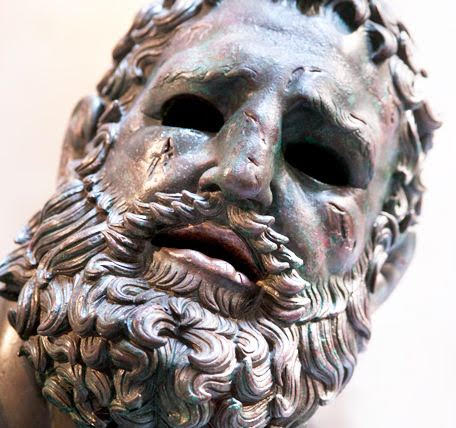

Prostitutes – women, men, boys, girls, eunuchs etc. – were at the bottom of the social scale, along with actors and gladiators. They could be adored by clients one moment, and shunned the next. And if a lupa was no longer profitable, the leno (pimp), or the lena (madam) might sell them off as a liability, sending them to a life that was possibly even worse.

In ancient Rome, prostitution was legal and licensed, and it was normal for men of any social rank to enjoy the range of pleasures that were on offer. Every budget and taste was catered to, and because of Rome’s conquests, and the length and breadth of the Roman Empire in the early 3rd century, there would have been slaves of every nationality and colour. Clients of the lupanar would have had their choice of Egyptians, Parthians and Numidians, Germans, Britons, slaves from the far East and anywhere else, including Italians.

However, even though prostitution was regulated, don’t kid yourselves. This was not a question of morality, or curbing venereal diseases. This was about maximizing profit – prostitution was also taxed!

In Pompeii, prostitution became a sort of tourist trade. On the street pavement you just had to follow the phalluses to find the nearest brothel! There were something like thirty-five brothels in the town, and that’s not counting the small curbside cells or niches where the cheapest lupae provided quickies to passers-by.

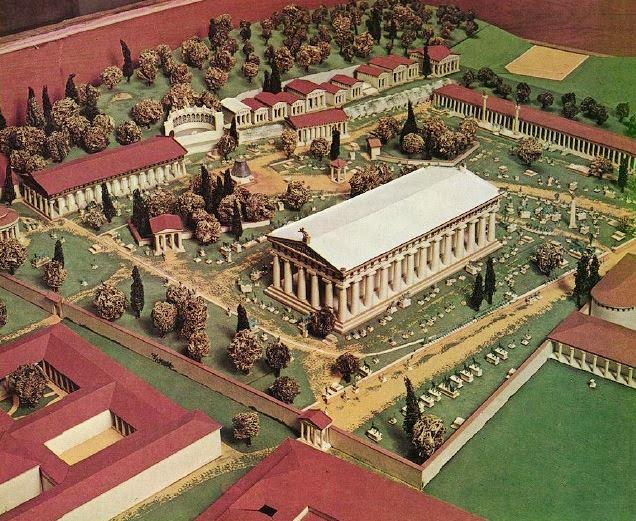

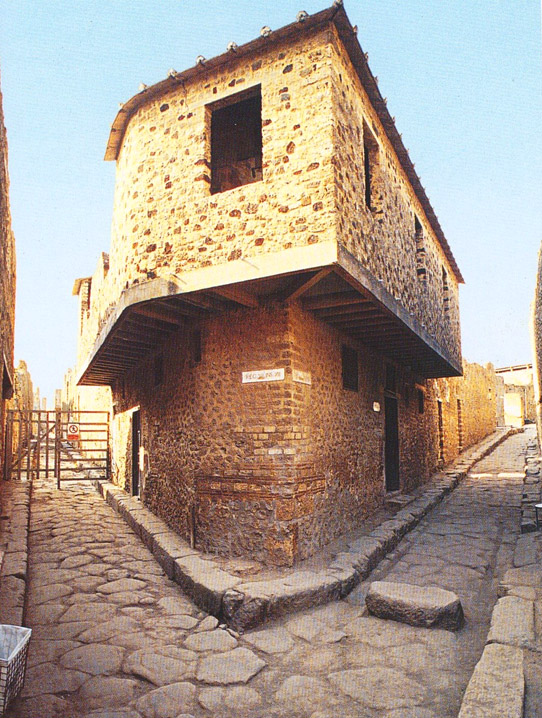

The Great Lupanar of Pompeii

The biggest brothel in Pompeii however, was the ‘Great Lupanar’ located at a crossroads two blocks from the Forum. Many of the frescoes pictured here are from that building which had ten rooms, where most lupanars had just a few.

But we’ve only been looking at prostitution and brothels in Rome and Pompeii. What would they have been like on the fringes of the Empire?

In Killing the Hydra, Lucius finds himself alone and in trouble in the Numidian town of Thugga. This is where he meets one of the secondary characters of the book, Dido.

Dido is a Punic girl who has lost her family and is all alone in the world. She is beautiful, and kind-hearted. But in a world where people were desperate to survive, those who didn’t have protection had few choices. For a young beautiful Punic girl on the North Africa frontier, there would not have been many places that offered a roof, a bed, food and clothing.

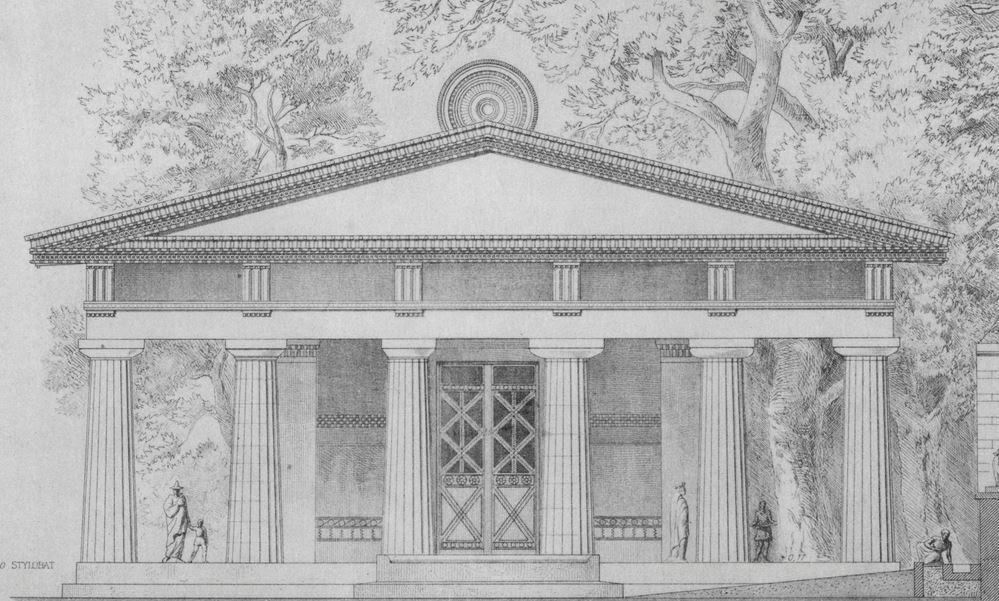

Wall painting from Pompeii

Dido is a prostitute in the Thugga brothel known as the ‘House of the Cyclops’, and she spots Lucius, a young, good-looking Roman walking by – a sure bet in her eyes, and perhaps better than her usual clientele.

But she doesn’t know Lucius yet. He’s not the average man out for a good time. He has much more pressing issues on his mind as he walks the streets of Thugga.

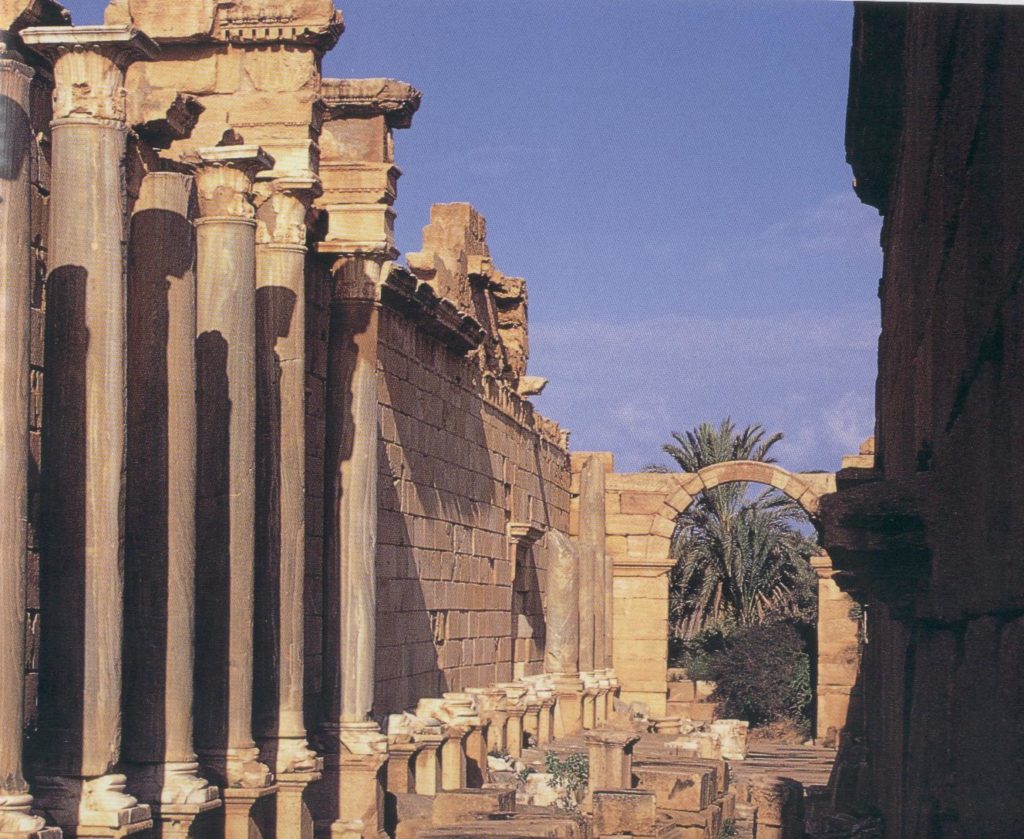

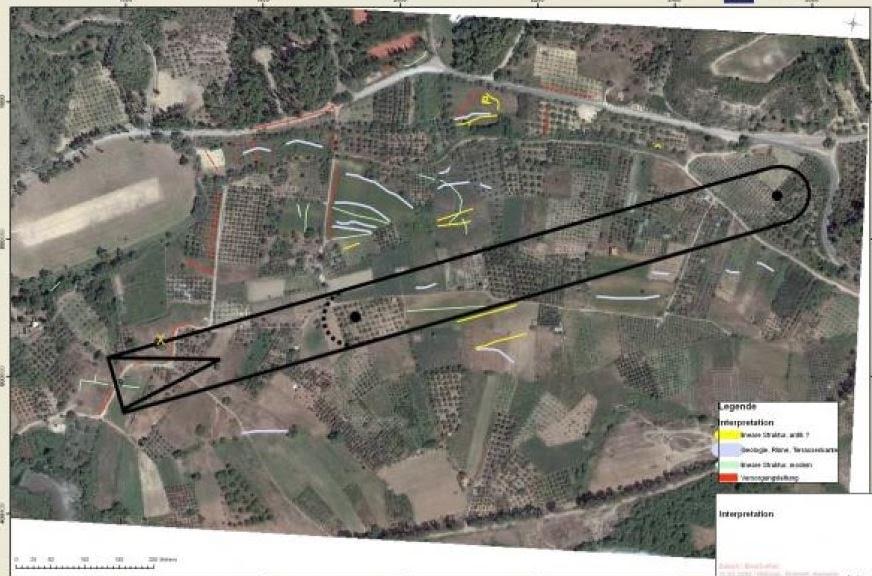

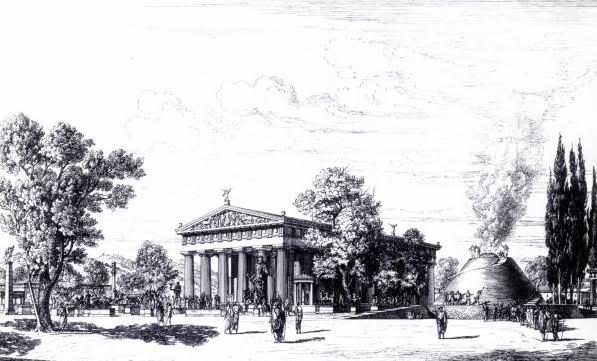

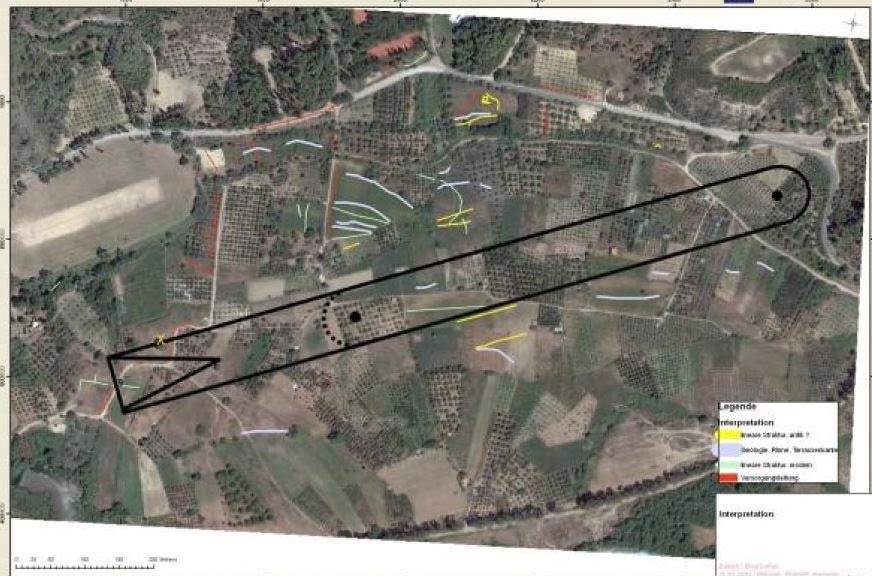

The ‘House of the Cyclops’ in Thugga, modern Tunisia

When I was doing my research for Killing the Hydra in Thugga (in central Tunisia), Lucius and Dido’s meeting played out in my mind as if they were walking alongside me.

Without giving too much away, Lucius ends up needing this young lupa’s help because he has no one else he can trust.

Can he trust this unknown, Punic girl? Will he go into the lupanar and seek her behind the curtain of her tiny cubiculum?

You have to read the book to find that part out. It is funny how one can find help in the most unexpected places!

One might think that the subject of this particular post was rather fun to write, that the images above are titillating. And sure, they are to an extent. I don’t mind a bit of risqué material on occasion. Why not?

But then, I can’t help thinking of the lives that these female and male prostitutes had to endure. Very few enjoyed the favour of kind wealthy clients, living in luxurious surroundings.

Prostitutes were slaves and most were probably pumped and beaten for a bronze coin or two before having to receive their next tormentor. These people were objects to the rest of the world, not human beings. They were people’s daughters and sons, mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers. In many cases they’d been taken from their homes on the other side of the world. Perhaps they were all that was left of their family?

For most prostitutes in the Roman Empire, life was a living Hades – just something to remember when looking at this aspect of the larger world of Killing the Hydra.

If you are interested in learning more about prostitution in the Roman Empire, the video below is an excellent documentary that will give you an inside look at the Great Lupanar of Pompeii.

Thank you for reading.

https://youtu.be/5uHuFYYO4go