The Autumn Equinox has come and gone, and a giant ‘Blood Moon’ made its round of the earth. From the photos I’ve seen, it was spectacular.

Harvest time is here.

However, in the city, it’s a bit difficult to feel a connection to harvest, our rural roots having been eclipsed long ago by fast, urban living.

In a small effort to reconnect with the earth and our western ancestors who were bound to it, I thought I’d mention a couple of traditions around what has been, for thousands of years, an extremely sacred time of year.

Of course, this is the time of year for Thanksgiving (earlier in Canada than in the USA) when we sit around the table en-famille and stuff ourselves like the turkeys that grace our tables. And wine, oh yes, and lots of it for the oenophiles among us.

But where does all this come from? Not the pilgrims, I can tell you that.

Apart from this being the time of year when summer gives way to fall, when the length of days is equal to that of nights, this time of year is when crops were harvested and preparations made for the coming winter.

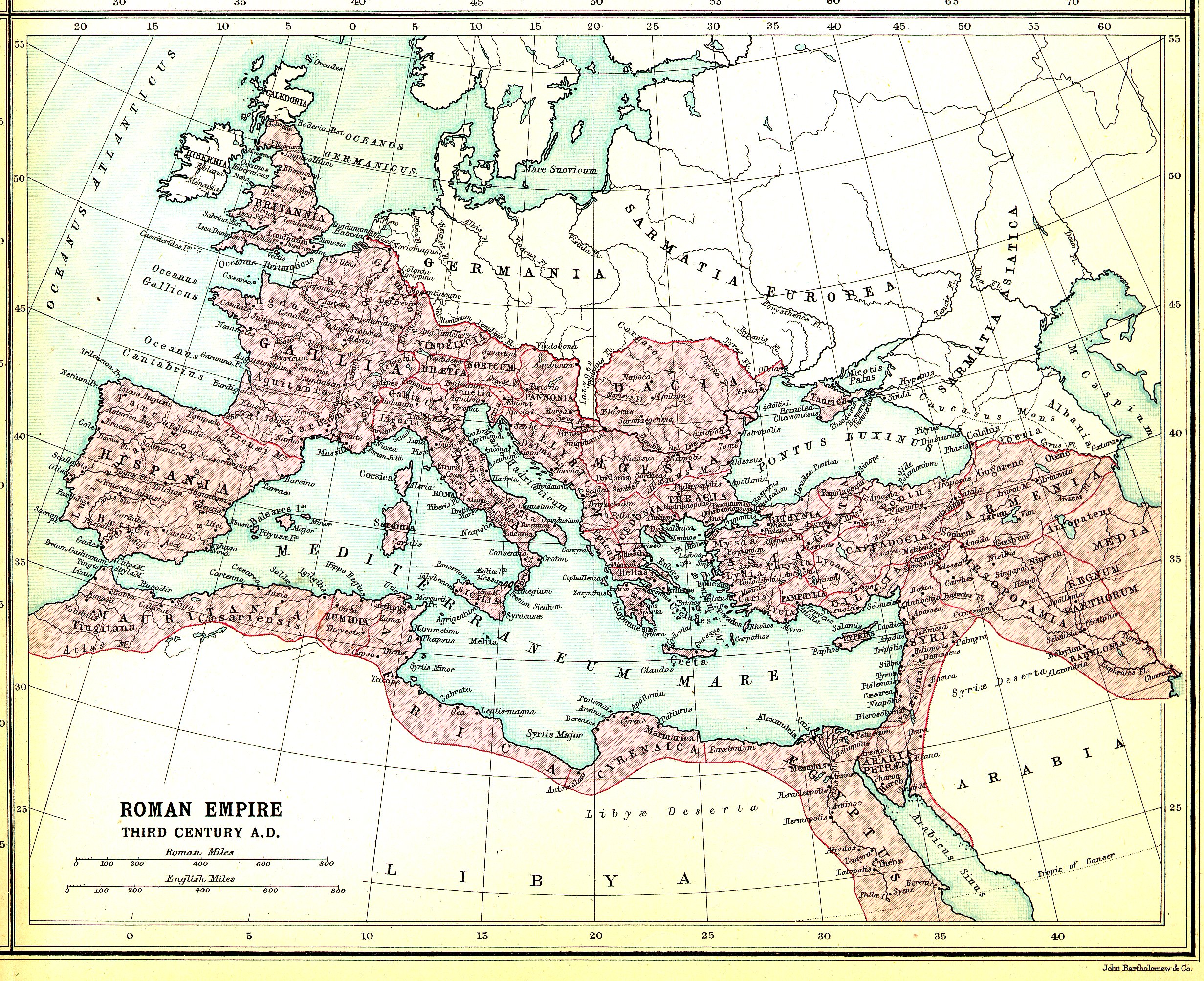

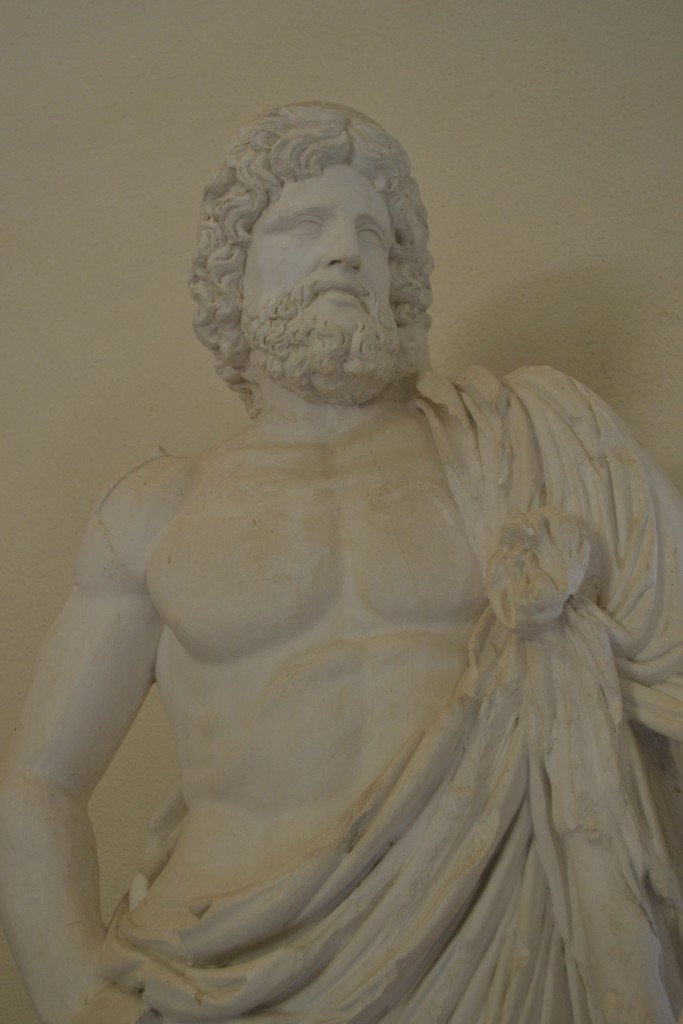

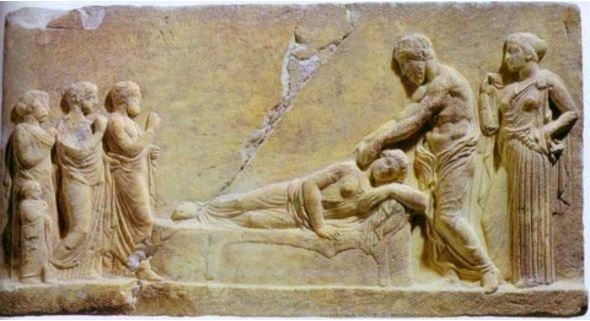

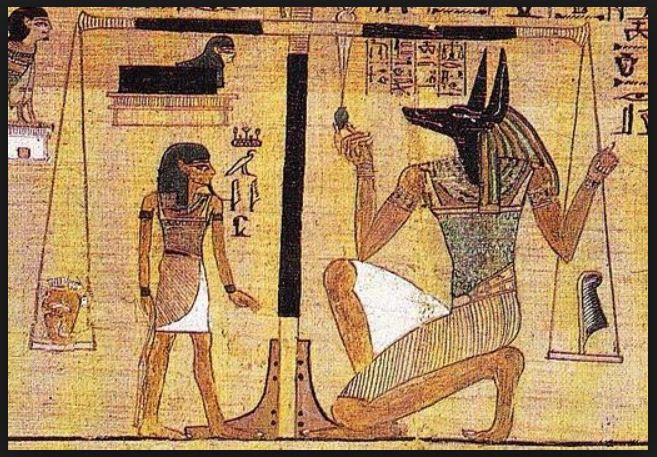

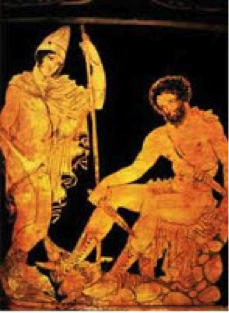

In ancient Greece it was the month of Beodromion and the festival Apollo, and the time for one of the most sacred rites: The Eleusinian Mysteries. The Mysteries were of course, in honour of the Goddess Demeter who was associated with crops, fertility, harvest and the protection of marriage. The Mysteries also honoured Persephone, Demeter’s daughter who would go to spend half the year in the Underworld with Hades. The time of harvest is associated with the death of agriculture and Persephone’s time away from her mother, the time Demeter would weep, wintertime.

The Goddess Demeter – Eleusina Museum

“Queenly Demeter, bringer of seasons and giver of

good gifts, what god of heaven or what mortal man has rapt away

Persephone and pierced with sorrow your dear heart? For I heard

her voice, yet saw not with my eyes who it was. But I tell you

truly and shortly all I know…

(from Hesiod’s Hymn to Demeter – Hecate to Demeter)

…But grief yet more terrible and savage came into the

heart of Demeter, and thereafter she was so angered with the

dark-clouded Son of Cronos that she avoided the gathering of the

gods and high Olympus, and went to the towns and rich fields of

men, disfiguring her form a long while.”

(from Hesiod’s Hymn to Demeter)

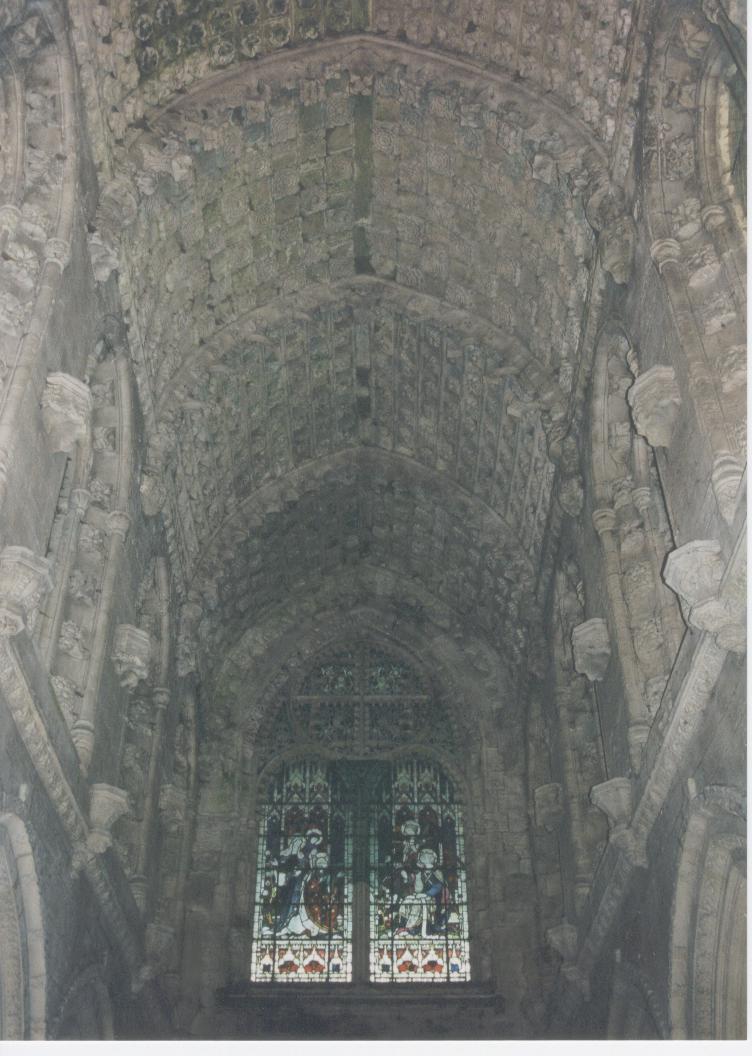

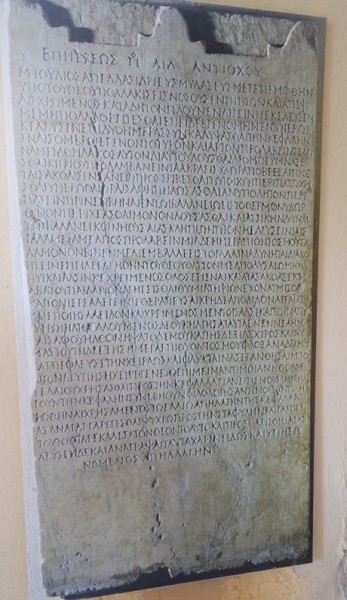

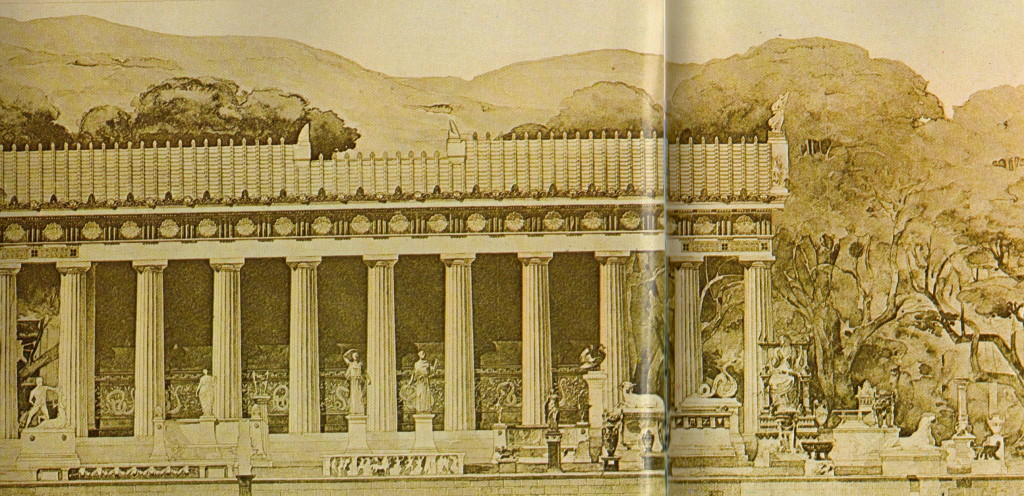

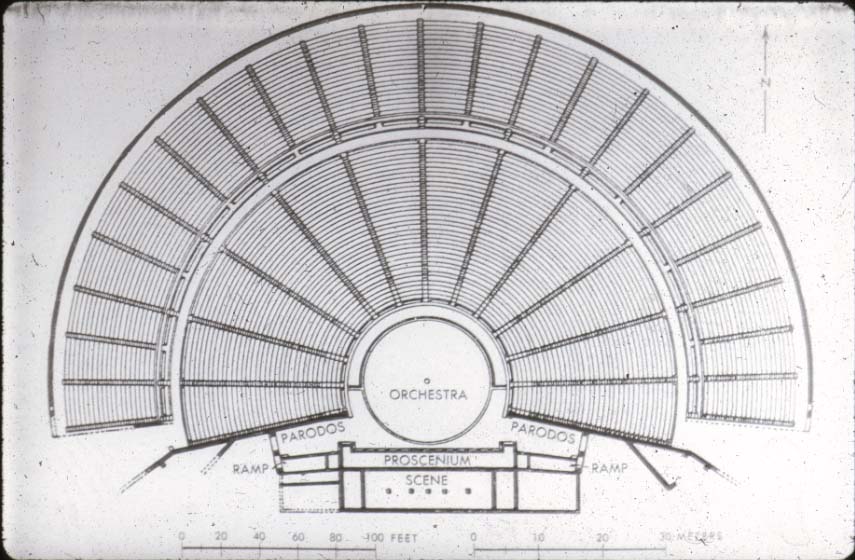

The cult of Demeter and Persephone existed for over one thousand years and Eleusis, one of the most sacred places of ancient Greece, was where the highly secretive ceremonies would take place in September and October. Sparse details about the ceremonies include bathing in the sea, sacrificing a piglet (not a turkey!), various sacred, secret objects, and a procession from Athens to Eleusis.

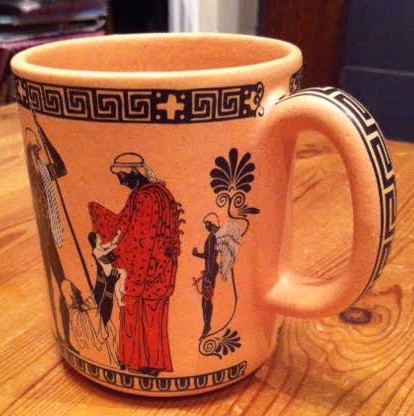

Symbols of the Harvest at Eleusis

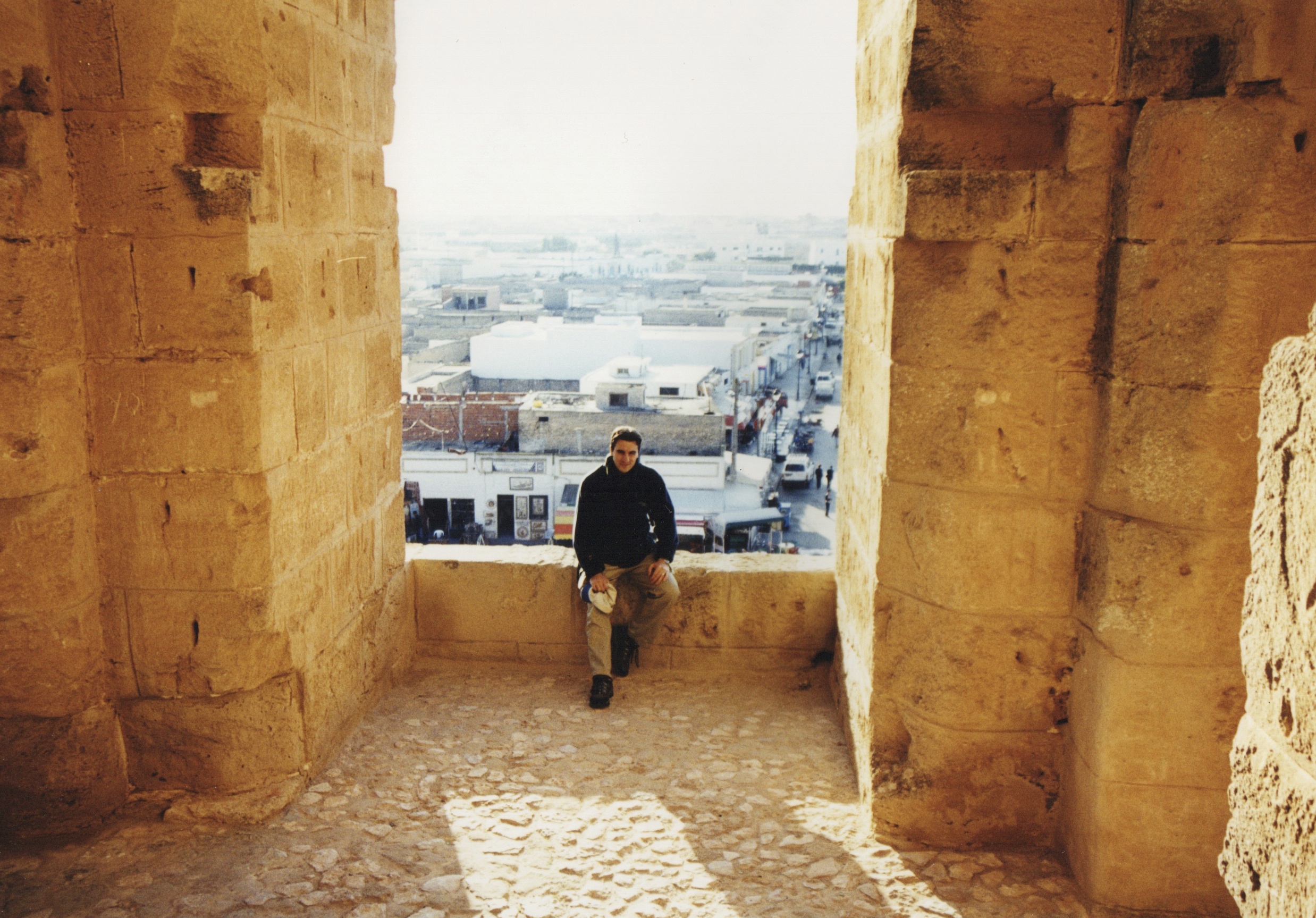

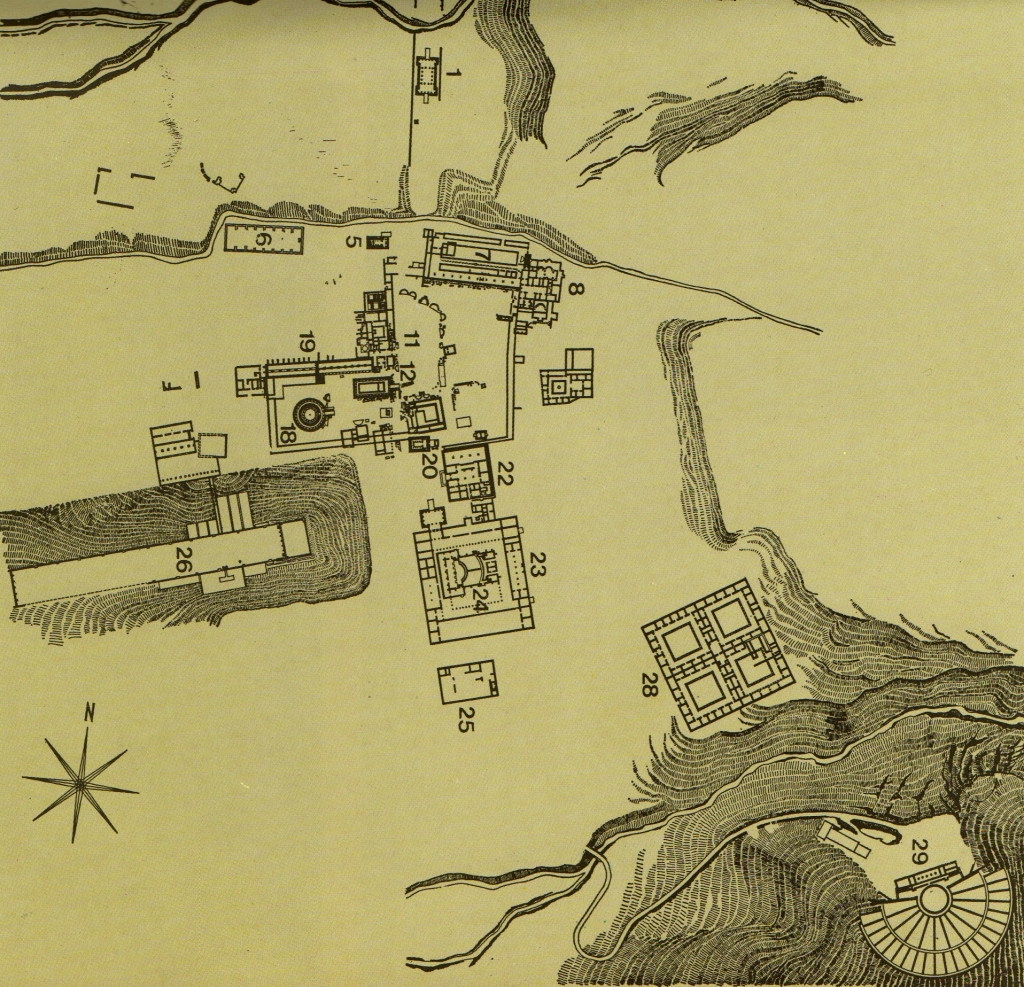

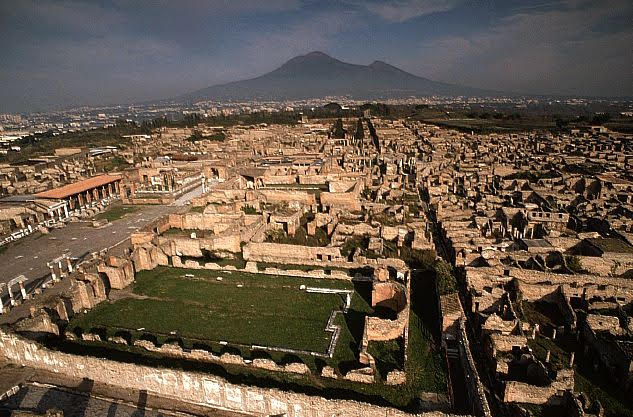

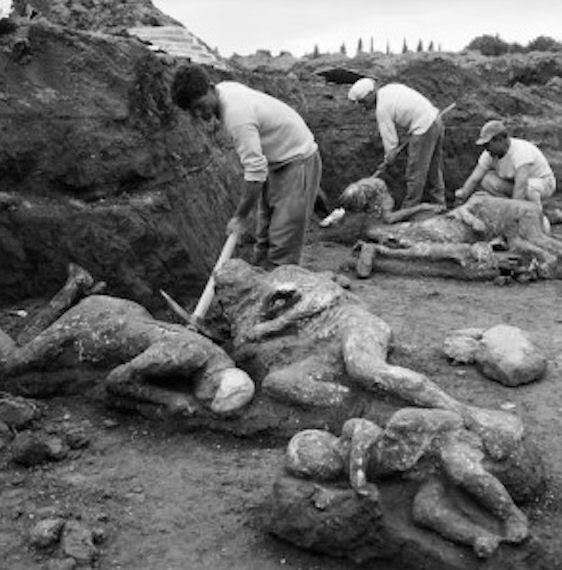

The site of Eleusis is itself an amazing archaeological site that is well worth the visit if ever you have the opportunity. Apart from the vast complex of temples, and other remains, you can see the cave where Persephone supposedly descended into the Underworld, a door to Hades’ realm. Facing the dark entrance is a well, known as the “Tears of Demeter”, thus named because of the goddess’ weeping in that spot. It’s a very moving place.

The ‘Gate to Hades’ at Eleusis

Let us not dwell too long in ancient Greece however, for our Celtic ancestors in Europe also revered this time of year. To the Celts, harvest time was also known as Alban Elfed (Welsh for ‘Light of Autumn’), and the Feast of Avalon (Feast of Apples) among other names.

To the Celts, this was the time of year when the acorns fell from the sacred oaks and the last sheaf of wheat was cut by a young maiden. It was a time of reverence and thanks for the Earth’s bounty, a time to harvest once more, and to slaughter animals before the onset of winter. An offering of apples would often be placed on burials to symbolize rebirth, hence the Feast of Avalon, Avalon of course being the ‘land of apples’.

Harvest time, to the Celts, also preceded the sacred festival of Samhain which marked the end of the light of summer and the beginning of winter’s dark. Again, the cycle of light and dark, birth and death is an ever present arch-type, a cycle of which our ancestors were keenly aware and for which they had a deep respect.

The Isle of Avalon – Tor and flood (photo by Lynne Newton)

So, as we sit to our laden tables this autumn, perhaps we should tip a bit of wine to the goddess who wept for her daughter’s departure into darkness, and for the end of light. When the harvest moon shines down on us in all its luminescence where we live in a world of concrete floors and steel girders, think of our forest and field-dwelling ancestors. They looked up at that same moon for ages from the dark circles of their sacred groves, and gave thanks for all they had.

Thank you for reading.