Another New Eagles and Dragons Series Release – The Stolen Throne is out now!

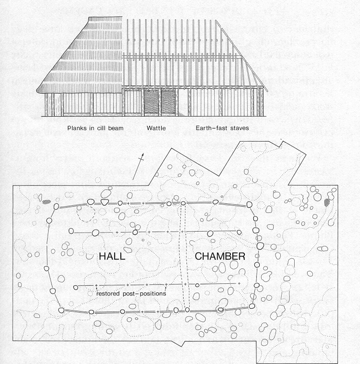

Last month, we announced the release of Isle of the Blessed, the fourth book in our #1 bestselling Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series. You can check that out by CLICKING HERE.

This month, we’re thrilled to announce the release of Book V of the Eagles and Dragons series: The Stolen Throne.

Here is the cover and synopsis of this exciting new addition to the Eagles and Dragons series:

At the peak of Rome’s might, a dragon is born among eagles, an heir to a line both blessed and cursed by the Gods for ages.

What happened to Lucius Metellus Anguis in the wilds of Dumnonia?

The Gods have finally granted Lucius and his family what appears to be a peaceful life in a new home surrounded by friends. The memories of pain and war are finally beginning to diminish.

But when Einion, Lucius’ friend and ally, sets out to reclaim his homeland from the man who murdered his family, Lucius knows he must help. Their quest takes them on a deadly journey beyond the reach of Rome, deep into Dumnonia, a mysterious and troubled land that has been ravaged by its false king.

As Lucius and his friends journey across the ancient moors, they rally support from unexpected allies. A plan is devised and the attack is set for the night of Samhain. They must all fight or die for the stolen throne of Dumnonia.

However, all is not as it seems. Lucius’ enemies emerge from the shadows, determined to isolate and slay the Dragon of Rome once and for all.

Does Einion finally reclaim his father’s stolen throne? What happens to Lucius upon the quest that changes him forever?

Step into a world beyond the veil as Lucius faces a deadly enemy and learns a truth that shakes the foundations of the world he knows and believes in.

This story will take you to a place beyond the reach of Rome’s Empire, a place full of mystery and emotion where all is not as it seems, a place from which few heroes return.

You haven’t read anything like this before!

You can learn more about The Stolen Throne (Eagles and Dragons – Book V) and find all the links to get your copy right here:

https://eaglesanddragonspublishing.com/books/the-stolen-throne-eagles-and-dragons-book-v/

The Stolen Throne is available in e-book format at all major on-line retailers, and currently in paperback from Amazon.

If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series, you can start the series for FREE with the full-length novel, The Dragon: Genesis, which you can download by CLICKING HERE.

Here’s to a new adventure in the Roman Empire!

Happy Reading!

The World of Isle of the Blessed – Part III – Ynis Wytrin: The Place Beyond the Mists

What is the Isle of the Blessed?

There are many traditions when it comes to paradise, or a place where there is no suffering or pain. To the ancient Greeks, the Fortunate Isles, or Isles of the Blessed were a place where heroes went, a green paradise where the sun always shone. To the Romans, that was Elysium, or the Elysian Fields, the place where heroes blessed by the Gods went to spend eternity in peace.

In the latest Eagles and Dragons series novel, Isle of the Blessed, we find ourselves in a world beyond the water and mist of the Somerset levels of southern Britannia.

In Part III of The World of Isle of the Blessed, we’re looking at the history, myth and legend of the place known in Celtic myth as Ynis Wytrin, but which we know today as Glastonbury, or the legendary Isle of Avalon.

Glastonbury has always been a special place for me, not because I lived in the countryside outside the town for a few years, or because of its strong Arthurian associations, an area of study and story that I have always gravitated to.

One of the things I love about Glastonbury is the, more often than not, peaceful coming together of various beliefs through the ages.

To most, the mere mention of this town’s name will likely conjure images of wild, scantily clad or naked youths and aged hippies. You’ll think of thousands of people covered in mud as they wend their way, higher than the Hindu Kush, among the tent rows to see their favourite artists rock the Pyramid Stage at Britains’ largest music festival.

It’s a great party, but that’s not the real Glastonbury.

Removed from the fantastic orgy of the music festival, this small, ancient town in southwest Britain is a place of mystery, lore and legend. It is a place that was sacred to the Celts, pagan and Christian alike, Saxons, and Normans. For many it is the heart of Arthurian tradition, and for some it is the resting place of the Holy Grail.

Today, Glastonbury is a place where those seeking spiritual enlightenment are drawn. The New Age movement is going strong here, yet another layer of belief to cloak the place.

When I lived there, I never tired of walking around Glastonbury and exploring the many sites that make it truly unique. I’d like to share some of those sites with you, sites that are featured in Isle of the Blessed, the latest Eagles and Dragons novel.

From where I lived on the other side of the peat moors, I awoke every morning to see Glastonbury’s most prominent feature shrouded in mist – the Tor.

Tor is a word of Celtic origin referring to ‘belly’ in Welsh or a ‘bulging hill’ in Gaelic. Glastonbury Tor thrusts up from the Somerset levels like a beacon for miles around. Every angle is interesting. On the top is the tower of what was the church of St. Michael, a remnant of the 14th century. Before that, there was a monastery that dated to about the 9th century A.D.

However, habitation of this place goes much farther back in time with some evidence for people in the area around 3000 B.C. It was not always a religious centre. In the Dark Ages, the Tor served a more militaristic purpose and there are remains from this period too.

In Arthurian lore, the Isle of Avalon is a sort of mist-shrouded world that is surrounded by water and can only be reached by boat or secret path. In fact, during the Dark Ages and into later centuries, until the drainage dykes were built, the Somerset levels were prone to flooding. This flooding made Glastonbury Tor and the smaller hills around it true islands. With the early morning mist that covers the levels, this watery land would have been a relatively safe refuge for the Druids, and early Christians, Dark Age warlords and medieval monks.

In Celtic myth, Glastonbury Tor, one of the traditional gates of Annwn, the Celtic otherworld, is said to be the home of Gwyn ap Nudd, the Faery King and Lord of Annwn.

Gwyn ap Nudd is the Guardian of the Gates of Annwn, an underworld god. It is at Samhain that the gates of Annwn open. This was also the place where the soul of a Celt awaited rebirth.

If you are on the Tor at Samhain, you may hear the sound of hounds and hunting horns as the lord of Annwn emerges for the Wild Hunt of legend.

In Arthurian romance, there is a tradition of the wicked Melwas imprisoning Guinevere on the Tor. Arthur rides to the rescue, attacks Melwas and saves Guinevere. This particular story mirrors an episode in Culhwch and Olwen, one part of the Welsh Mabinogion, in which Gwythyr ap Greidawl attempts to save Creiddylad, daughter of Lludd, whom he is supposed to marry, from Gwyn ap Nudd himself.

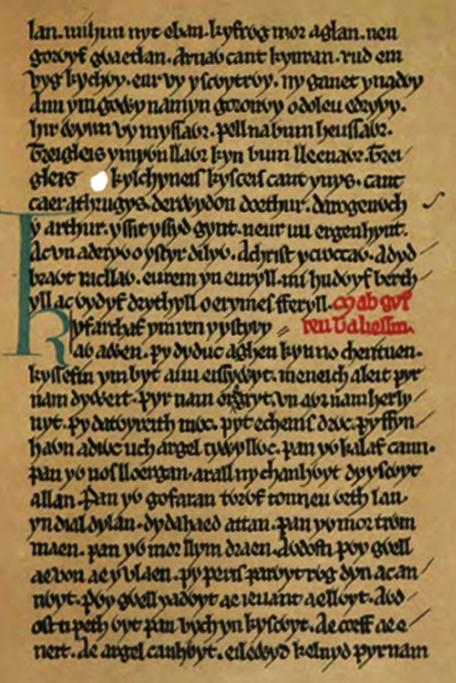

Another even more fascinating Arthurian connection can be found in a pre-Christian version of the ‘Quest of the Holy Grail’, called the ‘Spoils of Annwn’ which was found in the ‘Book of Taliesin’. In this tale, Arthur and his companions enter Annwn to bring back a magical cauldron of plenty. In this, some say that ‘Corbenic Castle’ (the ‘Grail Castle’) is actually Glastonbury Tor. It isn’t just Herakles and Odysseus who journeyed to the Underworld!

Glastonbury Tor is not only associated with Celtic religion, myth and legend. It is also said by some to be a place of power or a sort of vortex in the land that lies along some of the key ley lines, including what is called the St. Michael ley line. The majority of sites associated with St. Michael, the slayer of Satan, along the ley line were indeed places of power and belief of the old pagan religions.

Myth and legend persist through story and place, and the Tor is a prime example of how successive traditions do not overcome each other, but rather combine to make up the various aspects of that place.

If you ever get to Glastonbury, the Tor is a definite must. Walk to the top and sit awhile. Look out over the landscape and watch the crows and magpies dive in the wind around the steep slopes. Close your eyes and listen. While you’re there, you can decide whether you are sitting on a natural formation, a ceremonial labyrinth, a hillfort, a sleeping dragon, the Gates of Annwn, or the mound where Arthur sleeps until he is needed once more. The Tor is all of these things.

Another prominent feature of Glastonbury’s landscape is known as Wearyall Hill, located on the road as you enter from the neighbouring town of Street.

Wearyall Hill is home to one of Glastonbury’s most ancient treasures – the Holy Thorn.

Across the street from the Morrison’s store, you can climb up Wearyall’s gentle slope to see a hawthorn tree known as the Glastonbury Thorn, or the ‘Holy Thorn’. One popular legend associated with Wearyall Hill and the Holy Thorn is that in the years after Christ’s death, his uncle Joseph of Arimathea came with twelve followers by boat to Glastonbury. When they set foot on the hill, tired from their journey, Joseph plunged his staff into the ground and it took root.

There is archaeological evidence for a dock or wharf on the slopes of Wearyall Hill that dates from the period. Did Joseph of Arimathea actually arrive in Britain with the Holy Grail?

Stained glass detail from St John’s church in Glastonbury showing Joseph planting his staff in Wearyall Hill.

Well, that depends on what you believe. And Glastonbury is just that, an amalgam of beliefs living, for the most part, in harmony, just as the Celts and early Christians did here over two thousand years ago.

Cuttings of the Thorn grow in three places in Glastonbury. What is interesting is that this variety of hawthorn is not native to Britain, but is rather a Syrian variety. Curiously, it flowers at Christmas and Easter, both sacred times of year for Pagans and Christians. Every holiday season, the Royal family is sent a clipping of this very special tree that hails from the earliest days of Christianity in Britain.

The current Thorn is not the original, but rather a descendant of the original which was burned down by Cromwell’s Puritans in the seventeenth century as a ‘relic of superstition’. How much destruction has been wrought on the ancient sites of Britain during the wars waged by Henry VIII and later Oliver Cromwell? It’s horrifying to think about.

As with all other things in Glastonbury, Wearyall Hill and the Holy Thorn do not belong solely to the Christian past.

The hawthorn tree was one of the most sacred trees to the Celts and is the sixth tree on the Druid tree calendar and alphabet. It is also known as the ‘May Tree’ because of when it blossoms most. May was sacred to the ancient Celts as the time of the festival of Beltane, a time for Spring ritual and worship of the Goddess.

In the Middle Ages, the practice of picking hawthorn boughs evolved to include dancing with them around a May Pole.

In Arthurian tradition, Wearyall Hill is associated with the castle of the ‘King Fisherman’ whom the Grail knights meet. To reach the castle, those on the quest were said to have to cross the ‘perilous bridge’ over the river of Death. To pass through the castle was to go from this world to the next.

Interesting to think that the gates to the otherworld of Annwn were believed to be just on the next hill, Glastonbury Tor.

Whatever legend or myth you believe, or don’t believe, about Wearyall Hill is up to you. The stories are many and convoluted, but such is the fate of great and sacred places of the past.

I always looked forward to my walks up the gentle slope of Wearyall Hill with the Holy Thorn drawing me up like a beacon, a friend even. Locals, Christian and Pagan believers, hold it close to their hearts.

Once at the top of the hill, I would circle the Thorn, reach out to touch its limbs, and read some of the wishes or prayers on ribbons tied to it – ‘Don’t let me lose my family,’ or ‘Thank you for making my mummy better.’ The wishes wrenched your heart, and the thanks made you smile.

When I would sit on the nearby bench at the top of the hill, I never felt alone. I would look out at the Tor and the surrounding landscape and feel tremendous gratitude. I would always leave with a sense of hope for the future, and a tie to the past.

On my recent visit, long after the vandals struck, there are more wishes than ever upon the Holy Thorn.

When I returned to Glastonbury recently to film a documentary and do some research for Isle of the Blessed, I found the tree much changed from before.

In 2010, vandals took a chainsaw to the Holy Thorn in the middle of the night. In the morning, residents found their beloved tree of hope hacked to bits. A sapling was planted again in the Spring of 2013, but again, that was knocked down in the night.

I’m still in shock over this, lost in my remembrances of Glastonbury’s Thorn in full bloom on a sunlit hilltop.

But the Thorn has survived the centuries and there has been talk that new shoots have been coming up. The Royal Botanical Gardens is on the case, and so are the citizens of Glastonbury.

The Thorn and Wearyall Hill itself are not purely Christian or Pagan. They are symbols of unity, and of a common past. We should indeed cherish sites that are so revered, whether we believe in them or not.

In a way, the Thorn’s sacrifice is bringing people together. Glastonbury is still a town where Pagan and Christian live side by side.

And it is this unity that I explore in Isle of the Blessed.

I have every hope that the Thorn will blossom once again on the crest of Wearyall Hill, and that one day I’ll make the climb to say hello to a very old friend.

This next site we are going to look at is one that, like the rest of Glastonbury, is suffused with layers of history, legend, and belief.

The Chalice Well and surrounding gardens, located in a valley between Chalice Hill and the Tor, is one of those places that you don’t quite know what to make of at first. When you enter under the vine-covered pergola you are met by colour, soft light, and the gentle trickle of water playing about your senses.

You see young, wildly coloured blossoms exploding from the soil at the foot of Yew trees that have seen centuries of summers in Ynis Wytrin.

The same goes for the people visiting this place.

You will see young children frolicking like fairies at the edge of the water, adults of all ages contemplating beauty…life…death.

And you will find aged men and women, whose years are beyond the care of counting, strolling silently about the gardens. They’ll admire a particularly beautiful blossom or sit on one of the many benches hidden in private corners, perhaps remembering others they have come here with long ago. Or maybe they are just looking up at the Tor and harkening back to the tales of Arthur they loved when they too were children.

The thing about this place is its overwhelming sense of peace and harmony, from which all can benefit.

But what exactly is the Chalice Well?

Scientifically-speaking, Chalice Well is actually an iron-rich spring, the source of which is unknown. Some believe it comes from deep in the Mendip Hills to the north. The Chalice Well is where it comes out of the ground.

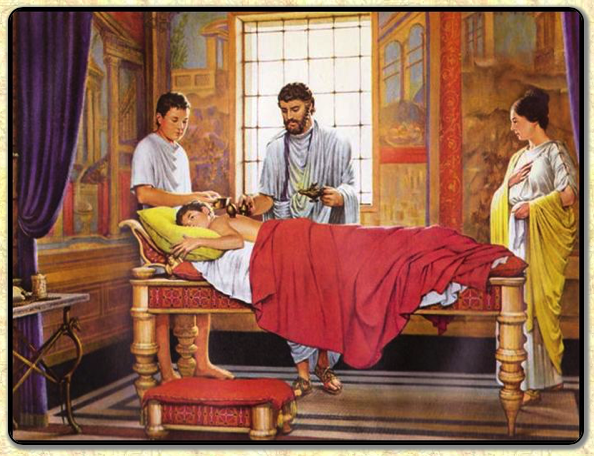

Springs were sacred to the ancient Celts. To those who inhabited this area from the pre-historic era on, the Well may have been a healing place beside the Tor. The waters that run red were sacred to the Goddess and were her water of life.

The spring has never failed, even in drought.

‘The Druids; or the conversion of the Britons to Christianity’. Engraving by S.F. Ravenet, 1752, after F. Hayman.

It is also believed that Glastonbury was the site of a Druid ‘college’ of instruction and that the avenue of sacred Yew trees, some still remaining in the Chalice Well gardens, were part of a processional way to the Tor, passing beside the Well.

Later legend, and the reason for the name given to the Well, relates how Joseph of Arimathea brought the Holy Grail to Glastonbury in A.D. 37. It is said that he buried the Grail near the Well and that the water runs through it, hence the redness of the water.

The Goddess’s blood was replaced by that of Christ, but the sanctity of the place remained (and remains) intact.

Of course, there is an Arthurian connection. Where you find the Grail, there too will you find Arthur and his knights.

In the 15th century, Sir Thomas Malory mentions the spring in his Morte d’Arthur when Lancelot and others are said to have retired as hermits in a valley near Glastonbury. Some believe it was this site that he referred to.

The sacred water of the Chalice Well feels like the beating heart of the gardens that surround it, and visitors, like a protective shield.

There are four places where the water surfaces in the Gardens.

The first is one of the most striking features – the well cover in the form of the Vescica Piscis.

The Vescica Piscis is an ancient symbol that represents the intersection of the material and immaterial (Natural and Supernatural) worlds. Fitting for one of the traditional gateways to Annwn.

The Chalice Well cover is made of English oak and wrought iron, and was designed after WWI by the architect and clairvoyant, Frederick Bligh Bond, who carried out the first excavations on Glastonbury Abbey.

The difference with this Vescica Piscis is that the circles are intersected by a sword, or bleeding lance, a Christian addition to this ancient symbol of power.

From the Well, the red water flows to the Lion’s Head where people can go to drink, or sit in quiet reflection while the water splashes onto a stone below.

Farther down the garden you come to a striking rich-red waterfall where the spring cascades into a pool where people can soak themselves in the healing water. This pool is another place of meditation known as Arthur’s Courtyard.

After that, the water flows past two ancient Yew trees, and a shoot of the Holy Thorn (yes, it survives!) into a pool shaped like the Vescica Piscis near where you enter the Gardens. The spring then flows away underground, beneath the Abbey and the pavement of Magdalene Street.

The red water’s healing sojourn above ground is fleeting, but for thousands of years it has brought people comfort, and peace.

Whenever I would visit Chalice Well and the gardens, my head pounding from a migraine, or the weight of a world of worries pressing me down, I would always leave feeling rejuvenated, calm, and optimistic.

Whether visitors are pagan, Wiccan, atheist, or Christian, or they adhere to some other system of belief, the Chalice Well is a place where people still believe in miracles, as they have done for thousands of years.

On the next part of our journey through Ynis Wytrin, or in insula Avalonia, we’re going to meet two very special giants.

They are tall, and broad, and green, and together they have stood the test of time. Their names are Gog and Magog.

The names of Gog and Magog will be well-known to Old Testament historians as evil powers to be overcome in the Book of Ezekiel (38-39), and in the New Testament Book of Revelation (20).

Gog and Magog also figure largely in the British foundation myths, mainly in the Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

According to Geoffrey, when Brute, a descendant of the Trojan Aeneas, came to Britain in around 1130 B.C. he and his people fought a West Country giant(s) named Goemagot.

There are many other tales and places around England and Ireland associated with the giants, Gog and Magog.

In Glastonbury it is different.

The giants of which I speak are two ancient and magnificent oak trees that are tucked away in this misty isle.

They are not war, or pain, or suffering. Gog and Magog represent the last of the great oaks of Avalon. They demand nothing of the wanderer, and yet they are revered.

The association with the giants only goes so far as the names of the trees, and their size.

The short walk to the oaks from the middle of Glastonbury town is one of the most beautiful walks in the area.

Cross Chilkwell Street, near the Abbey Barn, and head up Wellhouse Lane between the slopes of the Tor and Chalice Hill. Follow the foot path into the field where you will come to the ancient trail of Paradise Lane. At the bottom of Paradise Lane, you will find Gog and Magog waiting for you.

These trees are ancient, no doubt. When they come into view, you are drawn to them as if to a comforting grandparent. You’ll find the odd ribbon tied to a branch, or a sheaf of wheat laid in offering among the sturdy limbs.

These two trees are friends to many in Glastonbury and beyond.

Gog and Magog are all that remain of an avenue of oaks that led to the Tor, and which was thought to be used as a processional way by the Druids in ages past.

Sadly, the avenue was cut down for farmland in 1906, and these two giants are all that remain.

Oak trees like Gog and Magog were sacred to worshippers of the Great Mother, and later the Druids. Before Rome and mass farming came to Britain, the whole of the south of Britain was covered in forests from Hampshire to Devon.

Oak groves were sacred, the sites of the Goddess’ perpetually burning fires and the rites of the Druids who used oak leaves in their rituals.

The sanctity of the oak was not relegated to Celtic Europe either, but also goes back to ancient Greece. At the sanctuary of Zeus at Dodona, priests would glean the will of Zeus from the rustling of the leaves in the sacred oak groves.

At Glastonbury, Gog and Magog would likely have seen many a ritual or procession.

If they could only speak in a way we could understand, I’m sure they would have some fantastic tales to tell.

Taking the walk from town, past the Tor, and down Paradise Lane to see Gog and Magog was always one of my favourite walks. Because there are no roads nearby, the sound of cars is absent, and all you can hear is the chirruping of birds and the whisper of the wind as it blows across the Somerset levels.

When I returned there to do research for Isle of the Blessed, my feet found their way there once more, whisking through the dry field grass, or squelching through the mud, until I caught that first glimpse of the two giants.

“It’s good to see you again, after so long…” I thought, feeling a great comfort and sense of gratitude.

From my days in insula Avalonia, I can still recall refreshing walks along the crest of Wearyall Hill, along the dragon’s back of the Tor, and down Paradise Lane to Gog and Magog.

However, there is another place of peace, a sanctuary in the middle of town, nestled between Wearyall Hill, Chalice Hill, and the Tor. It is Glastonbury Abbey.

The Abbey grounds, like other sanctuaries in town, are a place to get away to. You have to pay to get in, but once you walk through the arch, past another descendent of the Holy Thorn, and onto the green lawns surrounding these magnificent ruins, you are set to experience a whole new aspect of Glastonbury.

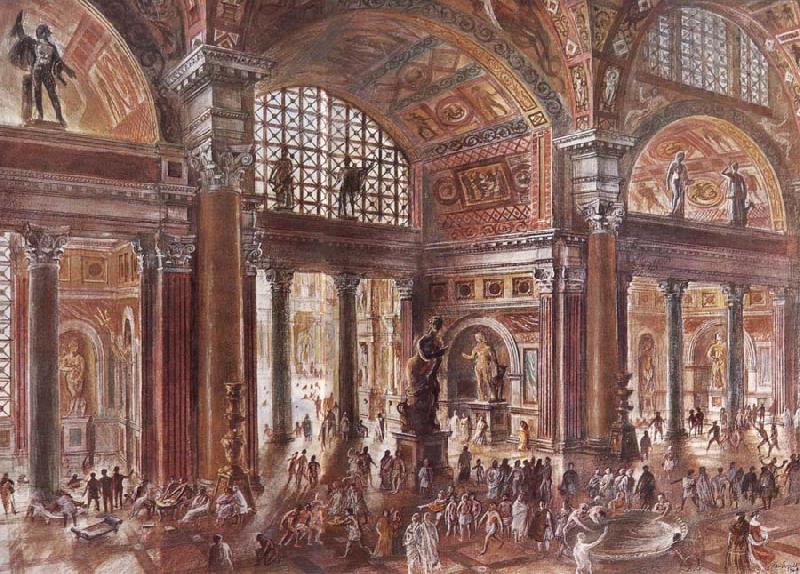

The ruins of what was once one of the largest abbeys in England rise up from the soft ground, sentry-still, surrounded by mist. ‘Majestic’ is a word I would use to describe the ruins, and ‘sad’. When you see the model of what the place looked like at its height of power and prominence, you understand.

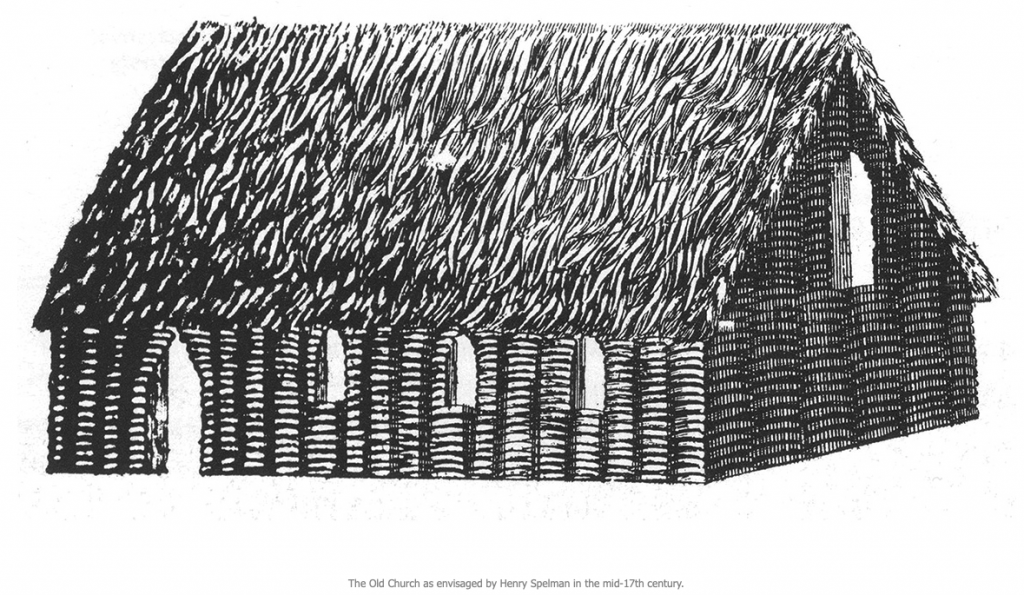

Glastonbury abbey was not always such a soaring monument of Christianity. The lovely ruins that can be seen today are a medieval creation, the remains of which date from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. But the place itself is said to be the site of the first Christian church and oldest religious foundation in the British Isles.

Model in the abbey museum of what Glastonbury Abbey used to look like before the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

According to tradition, Joseph of Arimathea and his followers built a wattle church on the site on land he was given by the local king, Arviragus (possible ruler of South Cadbury Castle at the time) around the middle of the first century A.D.

Circa A.D. 160, two Christians named Faganus and Deruvianus are supposed to have added a stone structure on the site of what is the Lady Chapel. It is here that there is an ancient well dedicated to St. Joseph.

In the early days of Christianity in Britain, this first chapel and the well were the predecessors of the magnificent ruins of the abbey we see today. The Lady Chapel was the site of the first Marian cult in Britain, and in the words of Geoffrey Ashe “there is no rival tradition whatsoever. When all of the fantastic mists have dispersed, ‘Our Lady St. Mary of Glastonbury’ remains a time-hallowed title.”

In one of the Welsh Triads, Glastonbury is given the distinction of having a ‘perpetual choir’.

It was a place that Christians gravitated to. Indeed, several Celtic saints are said to have come here, including St. Bridget, St. David, St. Columba, and even St. Patrick whom some stories name as the first abbot of Glastonbury.

Walking the grounds of Glastonbury Abbey is a contemplative activity, like so many other spots in insula Avalonia.

It is supremely peaceful and there are all manner of flora in the gardens to add to the calm. Great trees shiver overhead when a breeze blows into town from across the Somerset levels.

You can stroll the scant remains of the cloisters and up the nave with the abbey’s stone titans looming over you. In a couple spots, you can lift a wooden cover to reveal some of the colourful tiles of the medieval abbey floor.

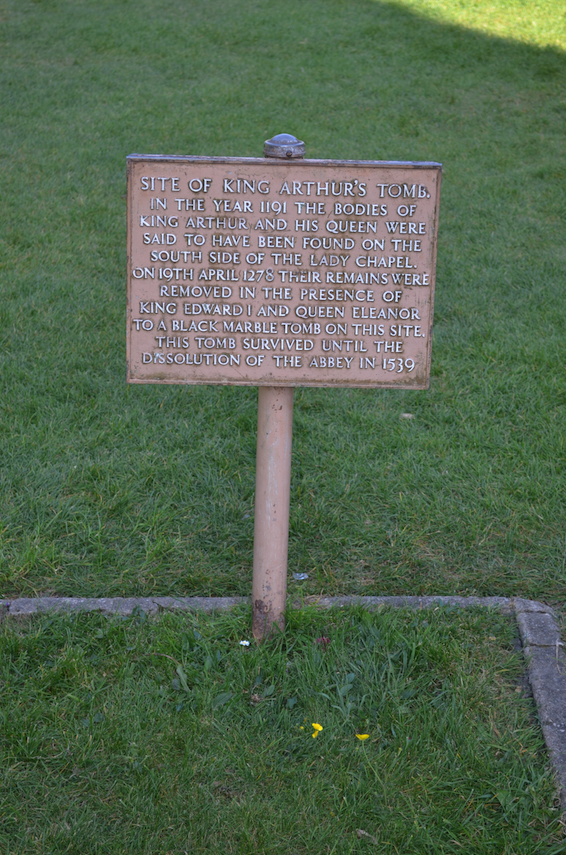

Then, toward the transept, you come to an unassuming outline in the grass with a plaque marking it.

This is where you meet with one of Glastonbury Abbey’s most mysterious connections.

In 1184 a fire ravaged the abbey and the monks needed to rebuild. Around the time of the fire, a Welsh bard is supposed to have revealed to King Henry II that King Arthur himself was buried within the abbey grounds.

The king passed this information on to the Abbot of Glastonbury who later ordered excavations to be carried out. In 1191, it is said that the monks found the bones of a man and a woman in a hollowed out tree trunk who were none other than Arthur, and his queen, Guinevere.

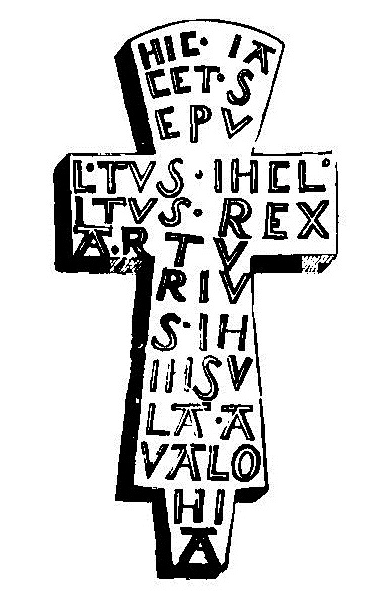

With the remains was a lead cross with the words ‘Hic Jiacet Sepultus Inclytus Rex Arturius in Insula Avallonia’ which translates as ‘Here lies buried the renowned King Arthur in the Isle of Avalon’.

The Elizabethan antiquarian, William Camden, did a sketch of the Arthur cross in the early 17th century.

A lot of doubt has been cast on the monks’ discovery with many believing that it was a hoax created by the monks to boost tourism through pilgrimage. The remains were treated as relics and later moved within the abbey during the reign of Edward I in the early 13th century.

It is important to note that the archaeologist who excavated the abbey in the 1960s, Dr. Ralegh Radford, indicated that the monks’ story might not have been that far-fetched, and that there was indeed a person of great import from the correct period buried in the graveyard just south of the Lady Chapel.

As with all things in Glastonbury, belief is always a part of the great equation.

There are other buildings associated with the abbey too, including the Abbot’s Kitchen where the Benedictine brothers would have prepared meals, and the Abbey Barn which is now home to the Somerset Rural Life Museum.

The site is lovely and inspiring. Tradition on the abbey grounds goes back ages to the very roots of Christianity in Britain and beyond, and this Christian presence comes as a surprise to the Romans who find themselves in Ynis Wytrin in Isle of the Blessed.

As I would sit on a bench, listening to the birds and the breeze, gazing upon the ruins, I would imagine St. Joseph arriving with his followers and picking out the spot for that first chapel. Perhaps they had something in common with the druids and priestesses of the goddess who might have already been there? Perhaps a common yearning for peace and truth?

It is sad that Henry VIII robbed us of the physical beauty of Glastonbury Abbey in the great Dissolution. The last abbot was dragged to the top of the Tor and beheaded by the King’s henchman, Cromwell.

For this place to function peacefully and unmolested from its earliest time, through Saxon incursions and Norman invasions, speaks to its agreed importance over the ages.

The majesty of this place may lie in ruins now, but its spirit and mystery certainly remain intact.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post on Glastonbury and The World of Isle of the Blessed as much as I enjoyed researching, revisiting, and writing about it in the novel. It was especially inspiring to write a story set in a place people of various beliefs lived together, and then to send my Roman protagonist into their midst.

What would a Roman think of a place where pagans and Christians, including Druids, lived together in peace and harmony?

Well…to learn that, you will have to read the book.

Join us next week for Part IV of The World of Isle of the Blessed when we will be taking a look at the main historical players in the imperial court in Britannia.

Thank you for reading.

The World of Isle of the Blessed – Part II – Roman Lindinis: The Small Town with Big Ambitions

Welcome back to The World of Isle of the Blessed, the blog series in which we take a look at the research, history and archaeology that went into the latest novel in the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series.

In Part I, we looked at the hillfort of South Cadbury Castle which is one of the major settings of the book. If you missed that post, you can read it HERE.

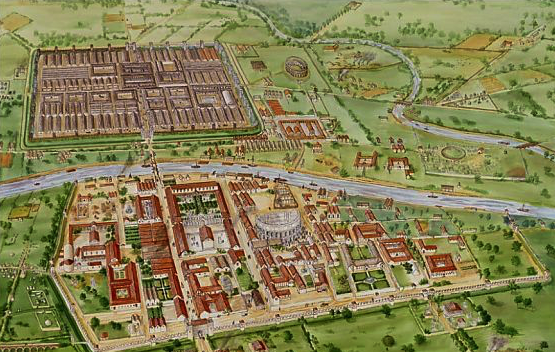

In Part II, we’re going to be taking a look at another place that plays an important role in Isle of the Blessed: Roman Lindinis.

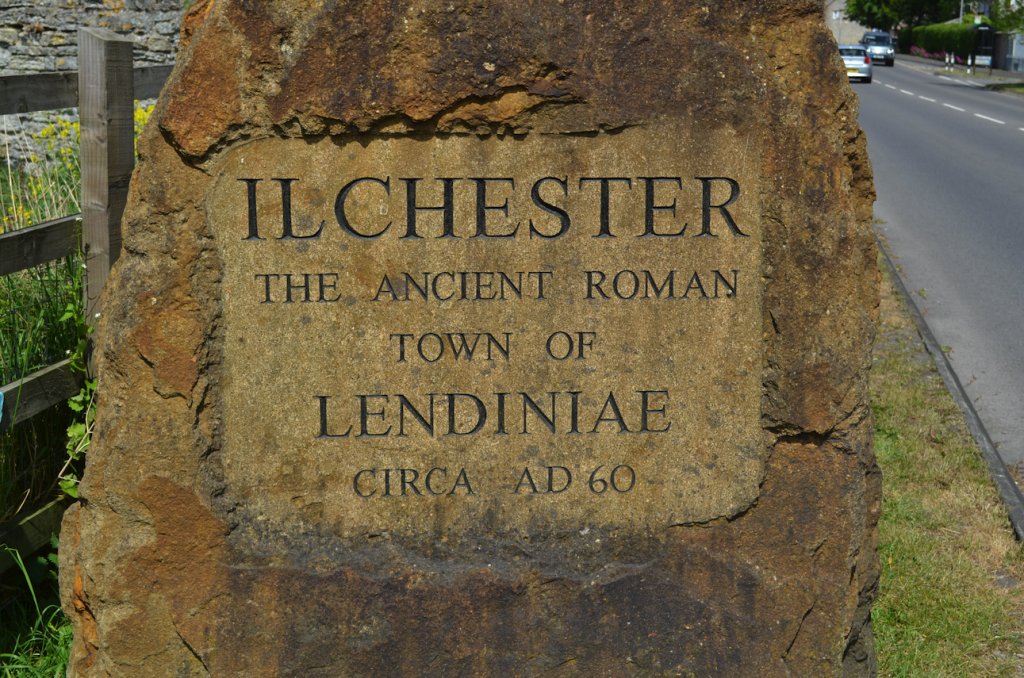

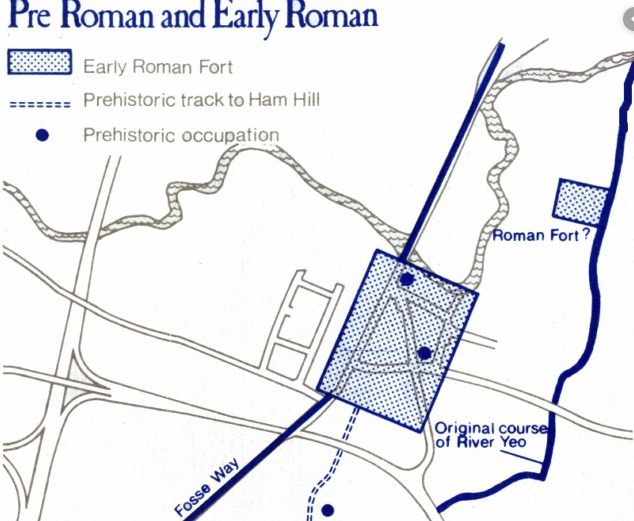

The settlement of Lindinis (also known as ‘Lendiniae’), as it is known in the seventh century Ravenna Cosmography (a list of place names from India to Ireland) is actually modern Ilchester, in Somerset, England.

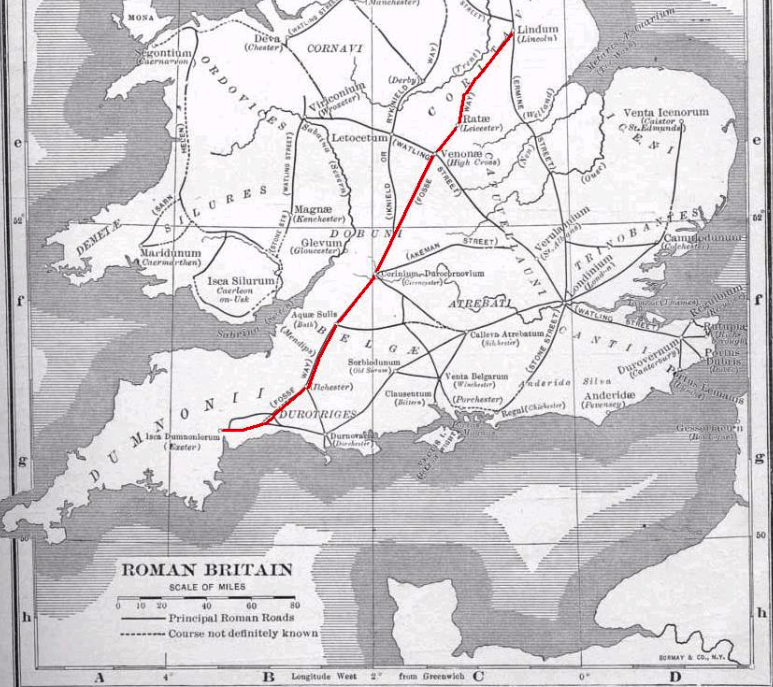

Lindinis, as it was known during the Roman period, was located just a few miles from South Cadbury Castle, and Glastonbury, Somerset. This fifty acre settlement lies where the Dorchester road interests with the Fosse Way, one of the major roads of Roman Britain.

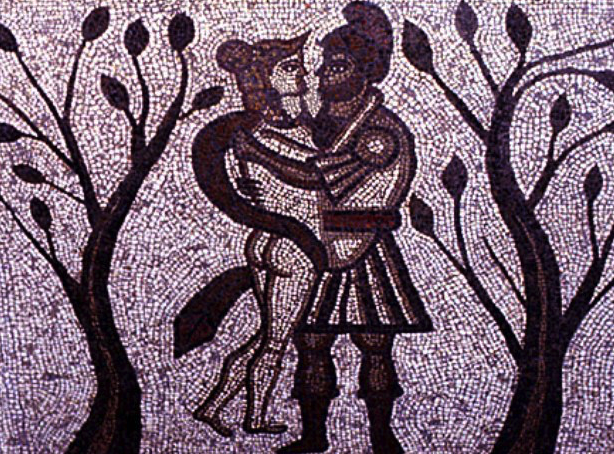

During the Roman period, Somerset was an agriculturally rich area of the Empire, with many villa estates, such as that of Pitney (which also features in the story). These estates’ primary business was in crops such as spelt wheat, oats, barley and rye. The also raised livestock, mainly cattle, but also sheep, horses, goats, and pigs.

These Roman villa owners were wealthy, and Lindinis was one of the main markets where they brought their crops and livestock.

Lindinis was not always a Roman settlement, however.

It was originally a Celtic oppidum, a native center that consisted of a large enclosure with homes, food stores and livestock. One imagines Celtic Somerset as a place of peace and vitality.

But, in A.D. 43 the Romans arrived with the advent of the Claudian invasion of Britain. Forty-five thousand troops marched over the land, including four legions, and the native Britons fought, and lost. Vespasian, the future emperor, stormed the southern hillforts of Britain, including South Cadbury Castle, ushering in an age of Roman domination.

Eventually, at Lindinis, two successive forts were built on the site to the south of the river: one from Nero’s reign, and another during the Flavian period. There is also evidence for a third fort to the northeast of the river crossing where a double ditch enclosure has been discovered.

The Roman invasion of Britain was a violent time, and that violence carried on through the Boudiccan revolt of A.D. 59. But when the blood stopped flowing, an age of Pax Romana settled on the southwest of Britannia, and Lindinis was at the heart of it.

Lindinis, however, was not the main settlement of Roman Somerset. To maintain peace and order, and keep the economy running, the Romans instituted various civitates, centres of local government in which tribal groups of the region participated.

The council of a civitas was known as an ordo, and the members of the ordo were decurions, overseen by an executive, elected curia of two men. The ordo of a civitas usually included Romans, tribal aristocrats or local chieftains, and it was their job to administer local justice, put on public shows, see to religious taxation, the census, and represent the civitas in Londinium. Supreme authority, however, belonged to the Provincial Governor who was aided by a procurator, the ‘tax man’.

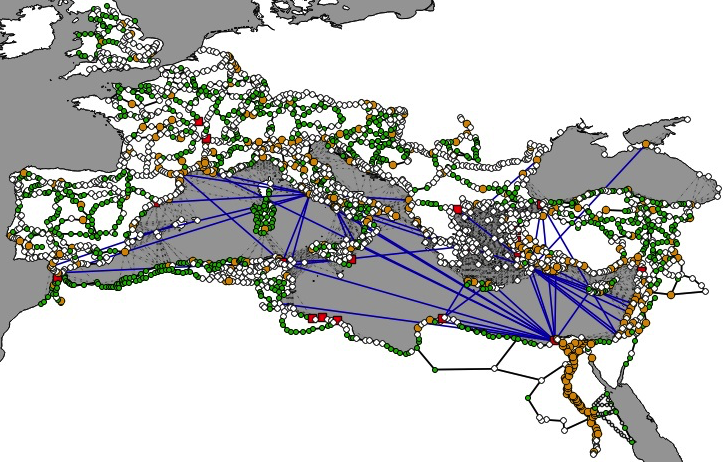

There were three major civitates during the Roman period in southwestern Britannia: Durnovaria (modern Dorchester) the civitas of the Durotriges tribe, Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter) the civitas of the Dumnonii, and to the north Corinium Dobunnorum (modern Cirencester) the tribal centre of the Dobunni.

Despite its large market and location at a crossroads along the artery of the Fosse Way over the river Yoe – in the southwest, the Fosse Way ran from Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter) to Aquae Sulis (modern Bath) – Lindinis was not one of the major civitates of the region, though it did rival nearby Durnovaria.

In addition to a thriving market where wine, oil, clothing, ornaments, jewellery, tools, pottery and glass were sold, Lindinis also had gravel and stone streets, and stone walls (later). People also came to Lindinis to pay their taxes.

Where the road diverges in Ilchester – the left to Exeter, the right to Dorchester. See the bridge over the river directly ahead.

There was also a small garrison.

Lindinis may have seen itself as the civitas Durotrigum Lendiniensium, but it could not be an official civitas as one of the requirements for civitas status was a basilica or forum. Lindinis did not have either of those.

Roman Lindinis had a large role to play in the economy of Roman Somerset, but perhaps not as large as its ordo would have liked. It also found itself in difficult situations during its time, for during the civil war (A.D. 193) between Septimius Severus, Pescennius Niger, and Clodius Albinus, Lindinis was forced to declare for Clodius Albinus who was in Britannia when he made his claim. At this time, new defences were built around Lindinis, as if in anticipation of the trouble to come.

In the book, Isle of the Blessed, Lucius Metellus Anguis, the main protagonist in the Eagles and Dragons series, has several run-ins with the ordo members of Lindinis’ ruling council who see him as a person of influence at the imperial court, a man who could help their small town to become much more.

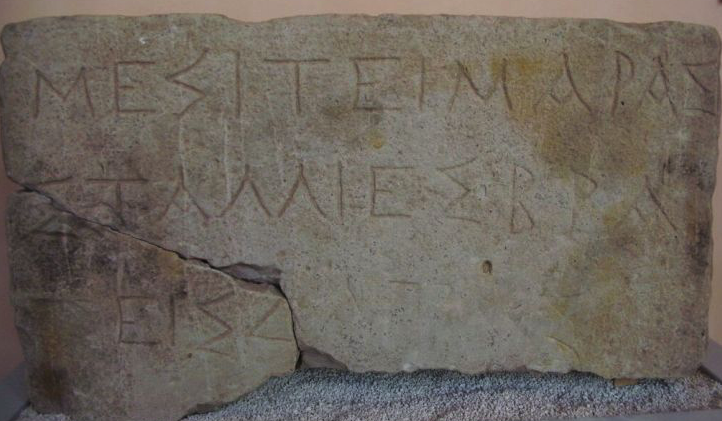

Historically, despite its lack of a proper forum or basilica, it seems that Lindinis did succeed in attaining a measure of civitas status, for along Hadrian’s Wall, two inscriptions have been found bearing the name of a detachment from the ‘Civitas Durotragum Lendiniensis’, or the ‘Lindinis tribe of the Durotriges’.

This, despite the presence of the other three, official civitas settlements Durnovaria, Isca, and Corinium.

Who knows? Perhaps the persuasiveness of the ordo members of Lindinis, the settlement’s important location, and the size of its market helped to sway the Roman authorities to grant civitas status.

In Isle of the Blessed, we see how far the local politicians are willing to go.

I hope you’ve enjoyed part two of The World of Isle of the Blessed.

Next week, in Part III, we will look at the history, myth and legend surrounding what is known in Isle of the Blessed as Ynis Wytrin, that is, Glastonbury, England.

Thank you for reading.

Isle of the Blessed is now available in e-book and paperback from all major on-line retailers. If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series yet, you can start with the #1 bestselling A Dragon among the Eagles for just 0.99! Or get the first prequel novel, The Dragon: Genesis, for FREE by clicking HERE.

The World of Isle of the Blessed – Part I – The Dragon’s Domus

Salvete, readers and history-lovers!

Welcome to The World of Isle of the Blessed!

In this seven-part blog series, we’re going to be taking a look at the research that went into my latest historical fantasy release, Isle of the Blessed, Book IV in the #1 bestselling Eagles and Dragons series.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll take you on a journey through the world of early third-century Roman Britain in which we will look at the history, archaeology, and historical events that took place during this pivotal time in the Roman Empire in which the book is set.

In this first post, we’re taking a closer look at a site that is well-known to Arthurian enthusiasts: the hillfort of South Cadbury Castle.

At the very south ende of the chirche of South-Cadbyri standith Camallate, sumtyme a famose toun or castelle… The people can tell nothing ther but that they have hard say that Arture much resorted to Camallate. (John Leland, Royal Antiquary, 1532)

The hillfort of South Cadbury Castle in Somerset, England, is one of the major locations in Isle of the Blessed. However, most people are familiar with it as a site with strong Arthurian associations. As such, its importance and role is hotly debated.

Though Isle of the Blessed is not a story of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, it is difficult not to speak of this important Iron Age site without discussing the Arthurian connection.

Was South Cadbury Castle the power centre of the historical Romano-British warlord, or dux bellorum, we know as ‘King Arthur’? Was this the actual site of what has come to be known in the popular imagination as ‘Camelot’?

I’ve always been a strong proponent of the theory that there was in fact, an historical ‘Arthur’ who formed the factual basis for all the legends we love and cherish. So, when I look at sites such as South Cadbury, I do so with that in mind. However, that doesn’t mean that I accept a site’s association with Arthur on faith alone.

I know this site pretty well – as I studied it and wrote about it as part of my Master’s dissertation entitled “Camelot: A look at the historical, archaeological, and toponymic evidence for King Arthur’s Capital”. As part of this, I looked at three of the main candidates for Camelot that had been put forward at the time – Wroxeter (Roman Viroconium), Roxburgh Castle (in the Scottish Borders), and South Cadbury. There is a copy of the dissertation hidden somewhere in the stacks at the St. Andrews University library in Scotland.

South Cadbury Castle is also where I cut my teeth as an archaeologist as part of the South Cadbury Environs Project team for a couple of seasons under the leadership of Richard Tabor. This was a wonderful experience that helped me to get up close and personal with the site I had studied for so long – I dug test pits, got into bigger trenches in which curious cows came to watch what I was doing, carried out geophysical surveys with a magnetometer, and found some curious objects such as a bronze dolphin that formed the handle of a Roman drinking cup.

Most of all, I was given the chance to spend more time on this amazing, and yes, magical, landscape.

And a couple years ago, when doing research for Isle of the Blessed, I returned to South Cadbury where I also filmed a mini-documentary on the site (coming out later this year!).

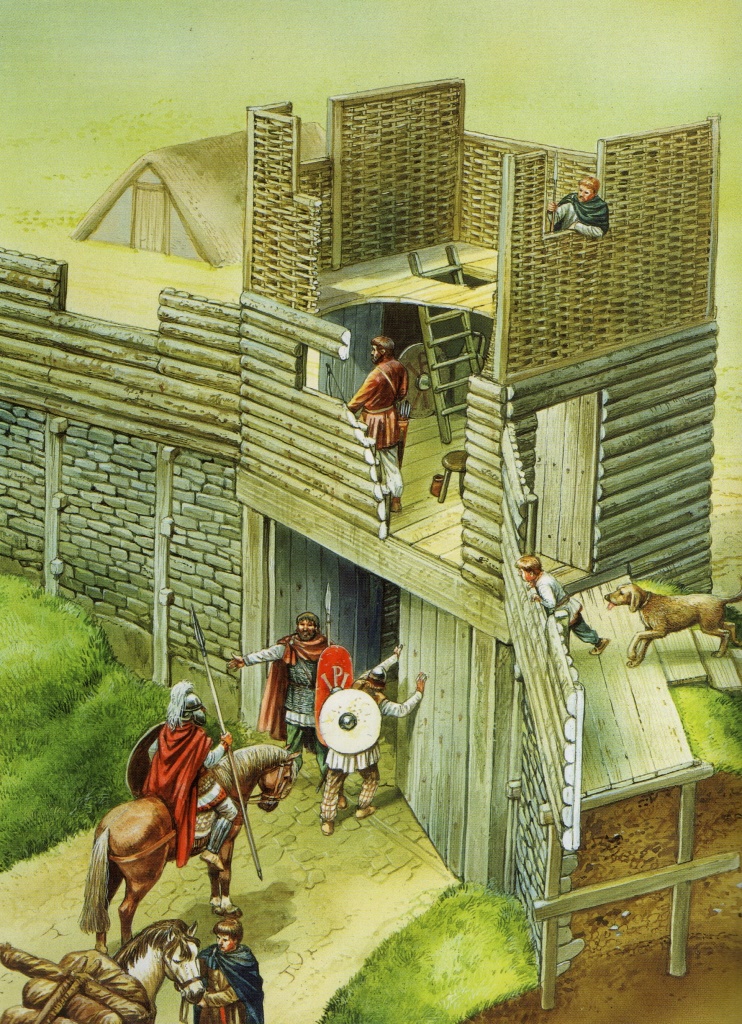

British Belgic Warriors of the Iron Age – Illustrated by Angus McBride (source – Rome’s Enemies 2 – Gallic and British Celts)

Before I give my thoughts on wandering the slopes of South Cadbury Castle, we should have a look at what it actually is.

South Cadbury Castle is not the late medieval castle with banners flying from tall towers that make up our usual image of Camelot. It is a 500 foot high Iron Age hillfort located in the pre-Roman era lands of the Durotriges. Occupation of the site began in the Neolithic period and it went through various stages of occupation from the 5th century B.C. onward.

By the time of the Roman invasion of Britain, it had four massive defensive ramparts with an inner area of about 18 acres. Access to the top was by two entrances, one to the north-east and the other, larger one, to the south-west. The Iron Age occupation of the site came to a violent end around A.D. 43 when Vespasian stormed the southern hillforts of Britannia.

The Romans made little use of the site, though there have been some theories that it was used as a Roman supply station. This theory is explored in Isle of the Blessed and the Eagles and Dragons series. In the 3rd and 4th centuries, there was renewed activity with visits being made to a Romano-Celtic temple that was built on the site.

Location of the Romano-British temple in the south-east sector of the hillfort of South Cadbury Castle

During excavations, a bronze letter ‘A’ was found that some believe belonged to this temple, which was perhaps dedicated to Mars, or some other deity.

However, when it comes to South Cadbury Castle, the periods that have always drawn me to it are the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. This period of the site is known as the ‘Arthurian’ period, and it is at this time, after Rome’s legions had left the island, that the archaeology shows a massive refortification of the hillfort.

6th Century British Warriors – Illustrated by Agnus McBride (source – Arthur and the Anglo-Saxon Wars)

Though it is much debated, South Cadbury’s association with the Arthurian period stems not just from hearsay and folklore. It has the archaeological evidence to back it up.

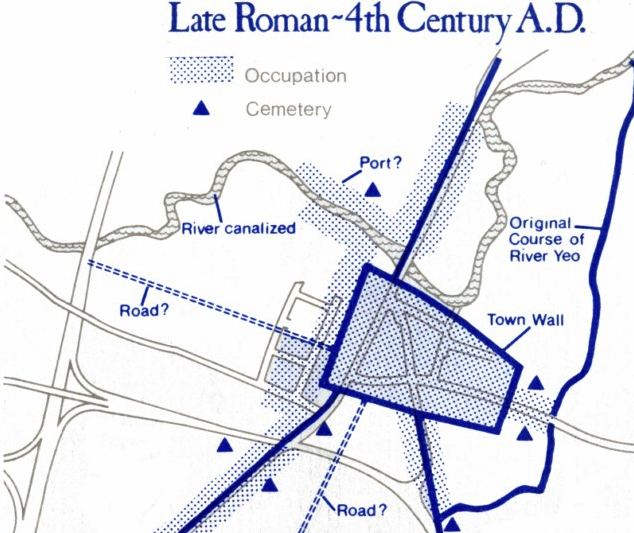

There have been a few big excavations of the hillfort over the years, but the biggest of all took place in the late 1960s and was headed by Professor Leslie Alcock. Professor Alcock and his team discovered evidence for a large scale occupation and refortification of the hillfort, during the Arthurian period, which showed repaired defences, including a strong gatehouse at the south-west entrance, and most importantly, several buildings, including a kitchen and a large timber hall on the fort’s high plateau.

The discovery of post holes reveals a finely-built timber hall that was on a large scale, measuring about 63×34 feet. This hall would not have been the great castle hall of late medieval romance, but rather something like the timber drinking halls of the period, more like to the Golden Hall of Meduseld, the seat of King Theoden in Lord of the Rings.

Another very telling discovery at Cadbury Castle was the large quantity of Mediterranean pottery that dates to the Arthurian period of activity. This is the same pottery type that was discovered at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, a site that also has strong Arthurian associations. One might think that shards of pottery from wine, olives and olive oil might be pretty mundane, but they anchor the sites strongly in the period, and also show that someone of importance was associated with the site. Not everyone could afford to import such things through trade.

The refortification of the hillfort during the Arthurian period was on a massive scale, and would have required many resources and men to hold it. South Cadbury castle was, in a way, on the front lines of the British struggle against the invading Saxons, and would have been well-placed to meet the Saxons as they advanced westward.

Based on the refortification, and evidence of the gatehouse that linked the ramparts running over the cobbled road at the south-west corner, this place was likely the base for an army that was large by the standards of the period. It may have been the site of the court of the dux bellorum, or the historical Arthur.

Artist Reconstruction of the South-west gate – Illustrated by Peter Dennis (Source – British Forts in the Age of Arthur)

I am only scratching the surface here, as far as the archaeological finds. For a more academic look at South Cadbury Castle, you will want to read the upcoming Historia series release Camelot: The Historical, Archaeological and Toponymic Considerations for South Cadbury Castle as King Arthur’s Capital. (Make sure you are signed-up to the mailing list be notified of that release)

South Cadbury Castle was finally abandoned in the early 11th century when it was being used as a royal mint during the reign of the Saxon king, Aethelred.

Today, South Cadbury Castle is a quiet hill in the midst of the Somerset countryside where it lies just south of the A303 motorway. The levels of its steep ring fortifications are now overgrown with trees and scrub, and cows roam the fields surrounding it.

When you visit, you pull your car into the small car park at the south end of the village of South Cadbury, just east of the hillfort. From the lane, you can’t really tell what you’re looking at. It seems like a steep, forested hill with a path leading up.

This path leads up to the north-east gate of the hillfort, and for me, it was always the gateway to another time, another realm.

It’s difficult to approach this site and reconcile the archaeologist/historian side of me with the romantic. Arthurian lore runs deep in my veins, and has had a hold on my psyche since I was very young. The first time I visited the site, I could almost hear the call of clear trumpets and the thumping of horses’ hooves upon the ground as knights returned home from their adventures, their horses brightly caparisoned, their armour shining brightly in the light of the Summer Country.

Of course, I know that is not how it was during the Arthurian period, but this is a place and story that fires the imagination. Cadbury Castle’s associations with Arthur include a hollow hill where he sleeps until he is needed again, the site of ‘Arthur’s Well’, a place on the slopes where his horse drank when he led the Wild Hunt, and of course the location of Camelot.

To me, however, the idea of South Cadbury as the main fortress of a Romano-British warlord leading a group of skilled cavalry in a last stand against the invading Saxons is no less romantic.

During my subsequent visits, I would ascend the dirt and rock path leading up to the northeast gate and pause with reverence for the history of the place. I would imagine looking ahead, up the slope to the central plateau of the hillfort to the great wooden hall where smoke from the hearth of Arthur’s hall wafted into the sky as he and his warriors discussed the fight for their lives and their Romano-British heritage.

The warriors that manned the ramparts of South Cadbury, who dined in the hall, and who rode out to meet the Saxons, have been wrapped in the fabric of myth, as much as the Isle of Avalon not ten miles distant, in Glastonbury. But they certainly left a mark on the place, on history and folklore.

As I walk the grass-covered ramparts of South Cadbury, watching the crows dive in the winds above the steep slopes, I can’t help but wonder if Arthur, Gawain, Bors, Tristan, Bedwyr, Cai and others walked that same path, a wary eye out for a sign of the enemy that would shatter the peace they had fought so hard for at the famed battle of Mons Badonicus.

Rarely have I felt so at peace and nostalgic as I have when walking around this hillfort. I can still smell the damp grass and feel the sun on my face. In my mind, I still watch the puffs of white cloud blowing over the Somerset landscape as I pause to gaze to the north-west and see Glastonbury Tor rising out of the earth.

In ages past, when the levels flooded, the distance between Cadbury Castle and Glastonbury might have been crossed by boat if you knew the way and which rivers to take. Indeed, one of the discoveries found around the hillfort was a boat.

South Cadbury Castle is, in some ways, closely tied to Avalon, and you can feel that as you look from the top of one to the other. This too is explored in Isle of the Blessed.

After making a round of the ramparts, and standing on the roadway of the south-west gate, I would always spend a good amount of time on the plateau, watching the sky and letting my imagination take hold.

The beauty of visiting a site, rather than looking at in a book or online, is that direct connection with the past, with the history of the place.

Yes, many of the stories we know and love about Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table are medieval fabrications. But I do believe that every legend has its base in fact, and so it’s a comfort to know that the layers of myth and legend are veined with elements of possible truth and history.

Many people will disagree, and that’s ok. When it comes to Arthur we will never reach a consensus.

However, considering the archaeological evidence at South Cadbury Castle, along with its location and the apparent activity during the Arthurian period, it seems quite possible that if there was an historical Arthur, he would undoubtedly have been familiar with this magnificent hillfort.

Was this just another strong point in the British defensive network? Or was it the Arthurian power centre that has come to be known as Camelot?

Whatever the answer is, it is surely fascinating, and perhaps unattainable. But then, that is what makes these historical mysteries so intriguing.

If you ever manage to roam the lands In Insula Avalonia, just be sure to make your way to South Cadbury Castle. Walk up the steep slopes, and through the gate, and know that you may just be walking in the footsteps of Arthur.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this first part of The World of Isle of the Blessed.

Be sure to tune in for Part II in which we will look the history of another setting in Isle of the Blessed: the village of Ilchester, Roman Lindinis.

Thank you for reading.

Isle of the Blessed is now available in e-book and paperback from all major on-line retailers. If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series yet, you can start with the #1 bestselling A Dragon among the Eagles for just 0.99! Or get the first prequel novel, The Dragon: Genesis, for free by signing-up for the newsletter HERE.

A New Eagles and Dragons Series Novel!

We’re excited to announce the official launch of Isle of the Blessed, Book IV in the #1 bestselling Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series.

Fans of this series have been waiting quite a long time for this book, but now the wait is over.

Sound the cornu and slam your gladii against your scuta!

Isle of the Blessed – Eagles and Dragons Book IV

At the peak of Rome’s might, a dragon is born among eagles, an heir to a line both blessed and cursed by the Gods for ages.

Emperor Septimius Severus’ war against the Caledonians has ended with a peace treaty. Rome has won.

As a reward for the blood they have shed, many of Rome’s warriors have been granted a reprieve from duty, including Lucius Metellus Anguis, prefect of the now famous Sarmatian cavalry.

The Gods seem finally to have granted Lucius a peaceful life as he builds a new home for his family upon an ancient hillfort in the south of Britannia. Lucius now finds that, after years of war and brutality, the most elusive peace, the peace within, is finally within his grasp.

But heroes are never without enemies, and Lucius, Rome’s famed Dragon, has many.

After an argument with traitorous local politicians, and a quest in which he is confronted by a dark goddess, Lucius realizes that his pastoral idyll is at an end. When war erupts in Caledonia once more, he is called away only to be assaulted on all fronts by his most deadly enemy.

The choices presented to Lucius by the Gods, his allies, and his friends are clear and terrifying. He can hand victory and power over to the wickedest men in the Empire, or he can fight for his life to create the world he believes in.

Will Lucius’ enemies and the powers of darkness overwhelm and destroy him? Or will he find the strength to survive the trials he faces and protect the people he loves?

This time, not even the Gods know…

We hope you like the sound of this one. It promises to take you on an adventure in the Roman Empire that you won’t forget, and the editorial team and beta readers have told us that this is Adam’s best book to date!

You can learn more and find all the links to get your copy ON THIS WEB PAGE.

Isle of the Blessed is available in e-book format at all major on-line retailers, and currently in paperback from Amazon.

If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series, you can start the series for FREE with the full-length novel, The Dragon: Genesis, which you can download by CLICKING HERE.

Here’s to a new adventure in the Roman Empire!

Happy Reading!

Guest Post: Discovering The Queen of Warriors with author, Zenobia Neil

We’ve got something special for you this week on Writing the Past!

Eagles and Dragons Publishing is thrilled to welcome back historical fiction author, Zenobia Neil, to talk about her latest epic, The Queen of Warriors.

Some of you may remember Zenobia from her previous post here, ‘Love is a Monster’, about the Cupid and Psyche myth and her novel, Psyche Unbound. If you missed that, you can check it out HERE.

In her newest novel, Zenobia takes us into the Hellenistic world for an amazing, epic journey. We’ve read this book, and it’s fantastic.

So, without further ado, let Zenobia take you into the world of The Queen of Warriors.

Discovering The Queen of Warriors

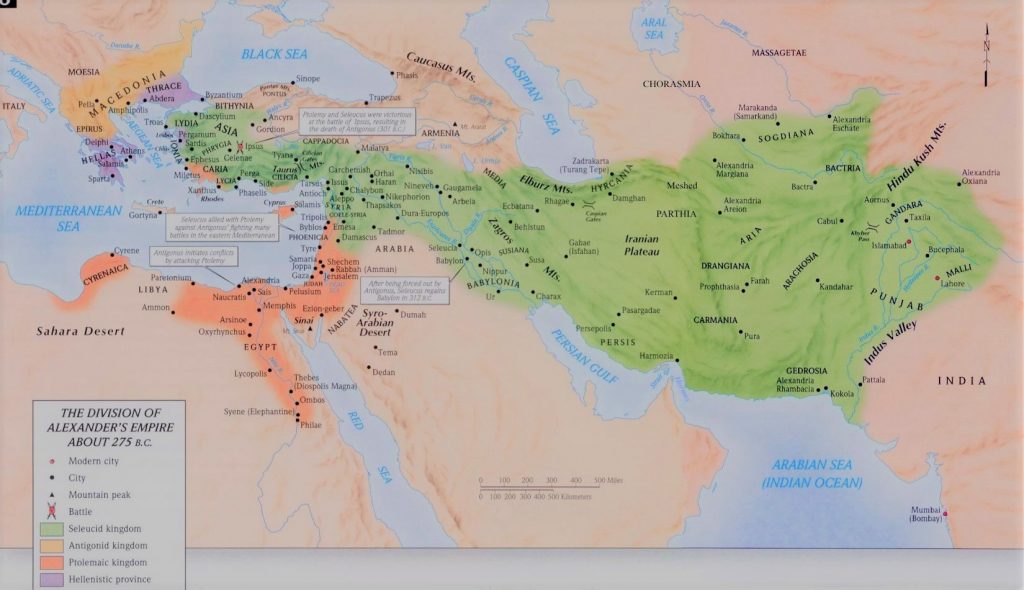

When I started writing The Queen of Warriors over seven years ago, my characters, a Xena: Warrior Princess type Greek warrior woman and a royal Persian rebel, came to me fully formed. However, I had no idea where and when the story took place. In the beginning, I was content with a kind of Xena fanfiction (without knowing what fanfiction was.) I began writing the story in a pseudo Greco-Roman world. That was fun, but I wanted to write real historical fiction. After re-reading Mary Renault’s The Persian Boy (a novel about Alexander the Great told by his eunuch Persian lover, Bagoas) I decided to set my story in the war-torn remains of Alexander the Great’s Empire.

My first serious research for this book yielded a lot of information about Alexander the Great’s life. I read about the Diadochi, the war of his generals. An early timeline I looked at made it seem that the important events that occurred were the conquests of Alexander, the death of Alexander, the War of Succession and then centuries later, Rome. (Sorry, Parthian Empire.) I wondered what life was like for people living in the former empire of Alexander. Ancient history might be recorded in centuries, but people live in decades, in years and days.

What was this period after the death of Alexander like? Alexander’s generals Lysimachus, Cassander, Ptolemy, and Seleucus divided his empire and fought with each other, while struggling to maintain their claims to rule at all. What would this have been like for Persians and Egyptians at this time? Ptolemy was able to condense his power in Egypt, a fairly easy transition compared to the other generals. His line lasted for generations and ended with Cleopatra. But Seleucus attempted to keep the lands Alexander had conquered in Persia—a vast expanse of diverse countries.

Before Alexander came, the Persian Empire created a vast network of satrapies—local governors who ruled over each local kingdom and sent taxes and intel back to the king. The Persian Empire had provided infrastructure. Alexander the Great had largely continued this practice, and he had brought some perks as well. Those who were his friends prospered; those who fought against him risked being killed, enslaved, or crucified.

But what did Seleucus have to offer? Why would any Persian, Mede, Bactrian, or Babylonian bow to him? Who would fight for him and why? These are the questions I wondered while trying to decide where in the former Persian empire my story would take place.

I had a National Geographic map that showed Alexander’s route, which I stared at every day. I tried to imagine where in this great expanse my story could take place. Eventually, it became clear that the story was set in Rhagae, a city near the Caspian Sea in what is now Tehran. I could clearly picture this fortress, the crenelated walls set against the backdrop of the snowy Elburz Mountains. Even before I knew his name, I knew my character Artaxerxes’s personality. As a Persian royal, he had grown up rich. He had golden armbands decorated with lynxes with ruby eyes. He had also learned to ride and shoot a bow as a child. He had trained for war since childhood, and he held truth and integrity above all else.

Writing the character of Alexandra of Sparta was a bit more of a challenge. Although originally inspired by Xena, Alexandra had her own demons, ones that would not be acceptable for daytime TV.

I needed to know Alexandra’s history and how she became a warrior. When I started brushing up on my ancient Greek history, the most recorded information came from Athens. It seemed impossible for an Athenian woman to learn to fight. I couldn’t help but be intrigued by the idea of Sparta, especially in juxtaposition with Persia. The classical age of Sparta was around 500 BCE. This made me wonder the same thing I did about Alexander’s empire after his death—what happened after?

There’s a tendency to think of Sparta as frozen in time, in the height of her power, with Leonidas as one of her two kings and every Spartan citizen a muscular warrior (Thanks, 300!). But that was just one period of time. History is many things, but it is always dynamic. We remember the highlights, but that doesn’t make up the time period of people’s everyday lives.

So what happened to Sparta? After the battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE, they lost their slave population, and with it their power. When he came to power, Alexander the Great forced them to join the League of Corinth. Later, some Spartans, like other Greeks, were offered land in Alexander’s former empire to help the Hellenistic culture continue. This, was how my main character, Alexandra and her friend Nicandor, the Little Red Fox came from Sparta to Asia Minor.

Sparta continued as a polis, though she lost her status as a major fighting force. Decades later when Sparta, like all of Greece and much of the ancient world was a part of the Roman Empire, Sparta became a tourist destination. Wealthy Romans came to watch a famous coming of age ceremony where boys were whipped at the temple of Artemis Orthia. What had once been a real rite of passage became a symbol of entertainment, and Sparta herself became a symbol of a classical strength that had once existed and then become nothing more than an idea of bravery and power.

This idea of Spartan hype stayed with me. Even if Sparta didn’t have the power it once did, being a Spartan carried weight and expectations. In The Queen of Warriors, Nicandor, The Little Red Fox, is Alexandra’s general, strategist, and advisor. He helps influence her power by spreading conflicting rumors that she’s an Amazon, a Spartan warrior, the Terror of the East. Being a woman warrior, a woman leader, she knows if she’s ever captured, terrible things will be done to her for daring to venture into a man’s world. So Nicandor makes her into a monster, too cruel to be crossed.

Once I figured out the time and place, I was able to let my characters really come through. I knew Alexandra of Sparta was a cursed warrior woman who wanted to atone for her crimes—I did not initially know what her crimes were—but it’s not hard to imagine a mercenary leader who hasn’t done terrible things. Using the Spartan angle, her advisor the Little Red Fox spreads rumors that she’s ripped out men’s tongues—when he actually finds people who’ve already lost their tongues.

There are no recorded documents of Spartan women warriors, only of the Spartans teaching girls as well as boys. Like any good ancient Greek education, this included physical activities. Unlike Athenian women, Spartan women knew how to manage their lands as well as households since Spartan men were often away. In certain situations, Spartan women could own land.

There have always been women warriors. Queen Tomyris of the Massaegetae, Artemisia I of Caria who fought for Xerxes, and Alexander the Great’s half-sister Cynane grew up in Illyria and was a warrior herself. And there have always been women who entered and competed in roles that were traditionally reserved for men. Readers of Adam Alexander Haviaras’s Heart of Fire will remember Kyniska, the Spartan princess who made Olympic history by winning a chariot race.

We’ve heard stories of women warriors from history, but there are also countless lives that were never recorded or whose positions were changed from leader to wife or concubine, or those whose histories were completely erased.

Alexandra of Sparta is not based on a real known person in history, but that doesn’t mean that someone like her never existed. In addition to learning about the past, imagining what could have been is one of my favorite aspects of writing historical fiction. More and more discoveries are being made showing how women were involved in roles that were traditionally thought of belonging solely to men. I’m delighted my characters came to me and demanded their story be told.

We’d like to thank Zenobia for a fascinating look at the history of this period and for sharing the inspiration behind The Queen of Warriors with us.

If you have any questions for her, please post them in the comments below.

We highly recommend this book, so if you would like to learn more and get a copy, just CLICK HERE.

Be sure to visit Zenobia’s website, and watch the book trailer at the bottom of this post as well.

Thank you, Zenobia!

Zenobia Neil was named after an ancient warrior queen who fought against the Romans. She writes about the mythic past and Greek and Roman gods having too much fun. The Queen of Warriors is her third book. Visit her at ZenobiaNeil.com

Praise for The Queen of Warriors

“The Queen of Warriors is a full-blooded adventure into the ancient and mythological world of the warrior queen, Alexandra of Sparta. Imaginative, exciting, and alluring!” – Margaret George, author of Helen of Troy

“A sizzling epic that will tempt you into the Hellenistic age. Neil’s writing is smooth, and anyone would be hard-pressed not to fall in love with her kick-ass heroine, Alexandra of Sparta!” – Adam Alexander Haviaras, Eagles and Dragons Publishing

“Bold, unexpected, and immensely satisfying. The Queen of Warriors is a game changer.” – Jessica Cale, editor of Dirty, Sexy History

“A surprising tale of retribution but also of redemption. Sexy yet thoughtful . . . unexpectedly moving.” – L.J. Trafford, author of The Four Emperor Series

Agora – A Visit to the Heart of Ancient Athens

Greetings readers and history-lovers!

It’s been a brilliant summer, but after some time off, new adventures, and a lot more writing, we’re back on with the blog.

It’s going to be a busy fall this year with some very exciting announcements coming up soon, so if you are not a mailing list subscriber, you should sign-up now so you don’t miss anything.

If you were following along on the Instagram feed, you’ll know that I was in Greece visiting with family for about five scorching weeks.

Normally, when we go back to Greece, we visit many archaeological sites, but this time, it was more about family and refilling the creative well. Besides, the days were so hot that it was bordering on dangerous. I can still feel the burning, crisping sensation on my arms!

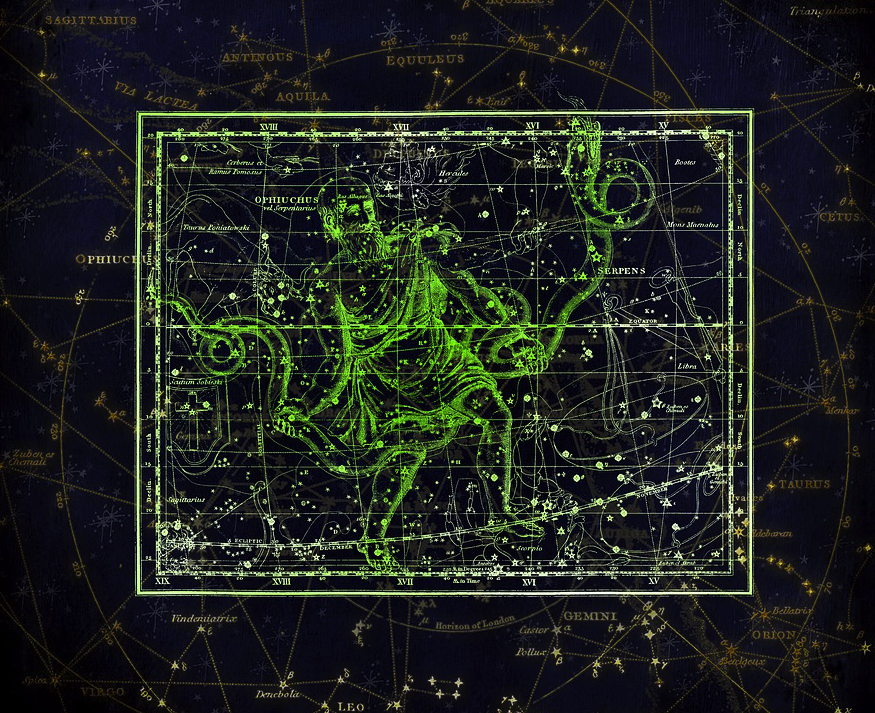

It was wonderful to hear and see that symphony of Greek summer – the gentle lap of water on pebbled beaches, brilliant sunrises that roused the chorus of cicadas, wine-filled sunsets watching the chariot of the sun disappear into the West, and night skies filled with legendary constellations – every day it was different and awe-inspiring.

I especially enjoyed the sweet scent of pine and wild thyme in the heat of day as I stared out the sky and sea, a world in myriad shades of blue…

But the historian in me would think it blasphemous to be in Greece and not visit at least one archaeological site. And so, after my seaside idyll in the Argolid peninsula, during my last couple of days in Athens, I made my way to the heart of the city to a site I had not visited in some years – the ancient agora of Athens.

Before I tell you what it felt like to return to this ancient place, here is a bit of history for those of you who are not familiar with it.

The agora has been the beating heart of ancient Athens since at least the sixth century B.C. I don’t mean human activity, for that goes march farther back. I mean that the agora has been the social, commercial, entertainment, political and religious heart of Athens since then.

Almost everything of import in Athens’ history happened in and around the agora, including the birth of Democracy.

The area of the agora is actually known as ‘Thiseio’. Years ago, when I first visited the agora, I asked about this and discovered that this stems from the mistaken belief that the intact temple of Hephaestus overlooking the site was a temple dedicated to Theseus, the legendary king of Athens (yes, Theseus who escaped the labyrinth!).

As part of the Theseus connection, there is a legend (mentioned by Pausanias) that a great battle took place on the site of the agora between the Greeks and invading Amazons who had been angered that Antiope, the sister of Queen Hippolyta and Penthesilea, fell in love with the Athenian king and returned there with him.

Antiope was killed during the battle, but Theseus and the Greeks were victorious nonetheless. As an aside, this tragic tale is depicted in a brilliant novel by Steven Pressfield, Last of the Amazons.

The ancient agora lies in the shadow of the Acropolis of Athens with the Areopagus (Ares’ Rock), Athens’ oldest court, to the southwest. Fun Fact: the Areopagus is called that because that is where the Gods tried Ares for murder. Murder trials continued to take place there during Athens’ history.

The agora is also flanked by the hill of Kolonos Agoraios, dominated by the temple of Hephaestus to the west, and the reconstructed stoa of Attalos to the east.

The Panathenaic Way, the road that ran from the great Dipylon Gate of Athens to the Acropolis, ran directly through the agora, as did the road to the ancient port of Piraeus.

The archaeological site is packed with ruins. In fact, excavations under the Archaeological Society and the American School of Classical Studies have been ongoing here since 1931.

The ancient agora of Athens is a place of many layers, and it’s no wonder, for it was destroyed several times in its history. The Persians destroyed it during their invasion of 480 B.C., and the Romans under Sulla did their dirty work in 86 B.C.

Later, in A.D. 267, the Herulians (a Scythian people from around the Black Sea) sacked Athens, and then the Slavs did the same in A.D. 580, not to mention the damage that was done during the wars of independence and other conflicts.

The stones of the ancient agora had born witness to a lot before being buried beneath the modern neighbourhood of ‘Vrysaki’.

I’m not going to go into every single monument that is visible today in the agora. There arsenal of ancient Athens, various stoas, the altar of Zeus Agoraios, the altar of the twelve gods, the temple of Ares, the Odeion of Agrippa, the library, and the temple of Apollo Patroos are just a few of the ruins you can wander around.

Click here for a 360 view of the Agora

Like many archaeological sites in Greece for me, a visit to the ancient agora of Athens is something more to be felt.

After taking the subway to Monastiraki station in the heart of the flea market and Plaka tourist district, we made our way through the thick and sweaty crowds, along tavernas with misting fans to the entrance on the northern side of the agora.

It seems all the world still comes to the agora of Athens. I counted about nine different languages alone in the line to get in. After a few minutes, we had our tickets and walked through to a spot away from the milling masses of snap-happy tour groups to look up and see the shining beacon of the Acropolis and the creamy white structures of the Erechtheum, Propylaea, and the Parthenon. It always fills me with silent awe to look up at that view, and the Agora is one of the best places to admire it.

To the far left, the Stoa of Attalos, where the museum is located, beckoned with its long shaded colonnades of cool marble, but we would leave that until last. Glancing up to my right, the sentry temple of Hephaestus upon the hill called to me, and so I began to make my way.

Thankfully, trees abound in the agora, so you can take your time and admire all there is to see from frequent pockets of shade brimming with cicada song.

I passed the site of the altar of the twelve gods and the overgrown ruins of the temple of Ares, unnoticed by most tourists, to stand before the imposing ruins of the Roman-build Odeion of Agrippa built in 15 B.C., and destroyed during the later Herulian attack. This spot is at the centre of the agora, and I stood there for a few minutes, gazing out from beneath the imposing statues of Tritons.

After a time pretending the murmur of tourists was the sound of ancient Athenians, I continued my walk to the altar of Zeus Agoraios, one of my favourite spots in the agora. How many offerings had been made there to the King of the Gods? The altar’s base is quite intact, and it stands in stony silence with the expanse of the agora before it, and the temple of Hephaestus and the ancient arsenal on the hill behind.

After watching most tourist by-pass Zeus’ altar as if it were just another pile of rocks, I turned around and looked up at the temple of Hephaestus, one of the most intact ancient temples I have ever seen.

The climb up is not long, but in that heat, I passed pockets of visitors resting in the shade of trees on their way up.

I couldn’t wait, however, and pressed on along the narrow, rocky path to the top.

There is something about the design of an ancient temple that appeals to my senses. I don’t know what it is. Perhaps is it is the simple lines that give one a sense of peace and order, or the ancient belief that it was where one communed with that particular god? Maybe there is something to the golden mean that permeates every aspect of those ancient structures?

I don’t know for certain, but when I am in the presence of such a beautiful structure, I fall silent. The fact that that temple is so intact makes it even more powerful.

I strolled around the perimeter of the temple, admiring the strength of its doric columns. When I reached the back, I stood peering inside, catching a glimpse of the ancient cella at its heart, so dark and quiet, cool in the middle of the inferno outside.

I had been to visit the temple before, years ago, but every time is like a first time in places like that. Our experiences change us between visits over the years. We notice new things, feel differently when we return, even though the sites themselves are frozen in time.

After admiring the temple, it was time to make our way back across the southern end of the agora toward the reconstructed stoa of Attalos. This route takes you back through the heart of the agora, along the length of the ruins of the middle stoa where you can see the rooms from which the ancient city was administered.

If you look up, you can see the Acropolis with even greater clarity, and the masses of tourists wending their way up like a flow of busy ants around a hill.

As I walked, there was much more to see, but the heat was intensifying. Some things would have to wait until the next visit.

The stoa of Attalos, built in the second century B.C. by that King of Pergamon (159-138 B.C.), was busy with people taking refuge from the shade, talking, resting, shopping in the museum shop, and admiring the remnants of Athens’ great past. You could hear tour guides teaching their groups about this history of Athens, Greek visitors talking politics, and others taking in the view and discussing the next part of their journey in Greece. The scene, apart from the clothing and languages spoken, might not have been that different from two thousand years before.

As for me, I made my way into the small museum that is housed on the ground floor of the stoa. Don’t let the size of this museum fool you. It houses a wonderful collection of artifacts from the full range of Athenian history in the agora from early Bronze Age tombs, through the Geometric period, the Classical period, and into the Hellenistic and Roman ages.

One of my favourite pieces was a three-handled bowl of which I had recently bought a wonderful replica from our friends at the Ceramotechnica Xipolias in ancient Epidaurus.

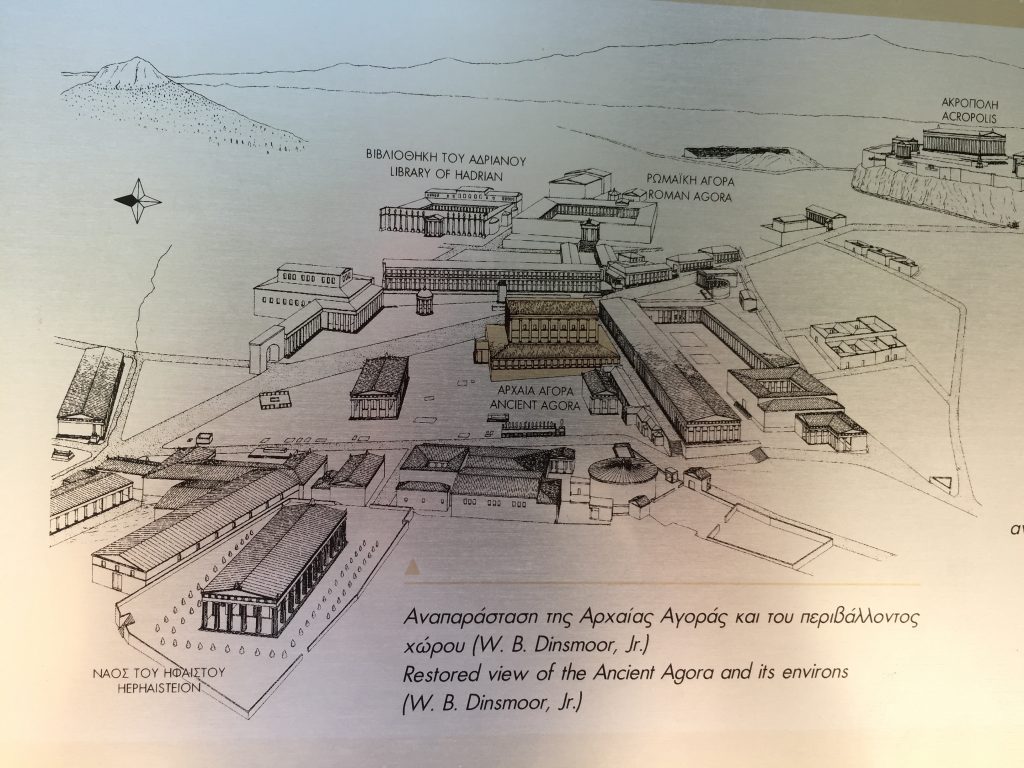

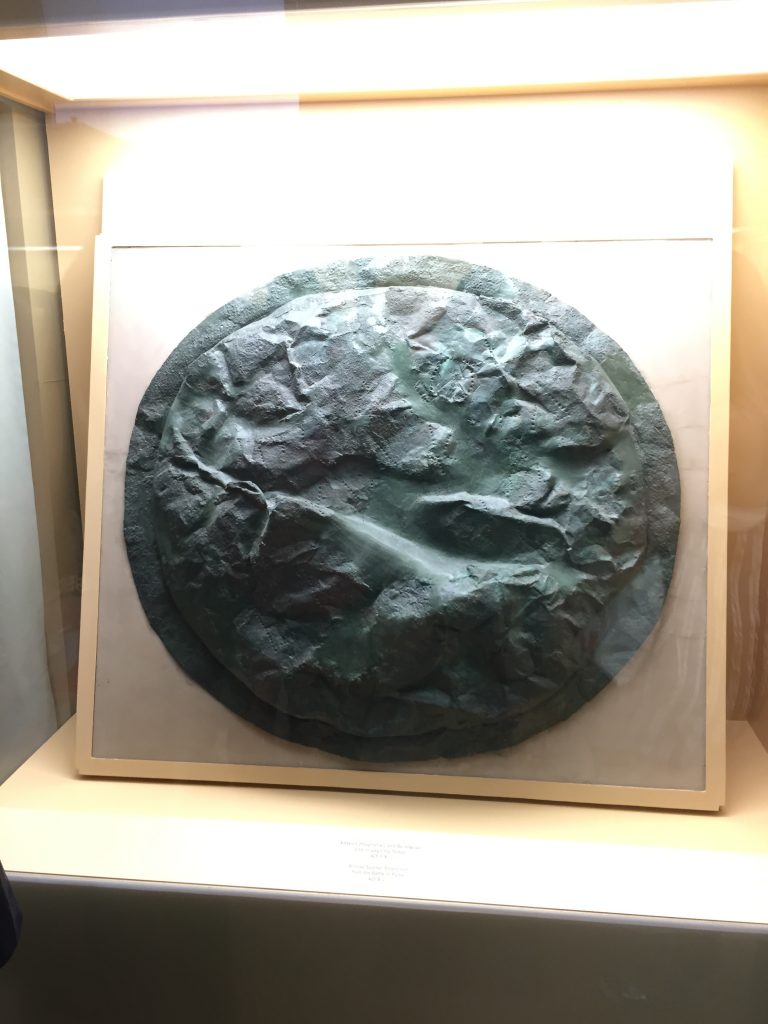

Here are a few of the wonderful artifacts that are in the museum of the ancient Agora:

After we were finished in the museum, there was one more surprise left in the stoa. If you go to the north or south end of the stoa you will see stairs leading to the second level.

We snaked our way up the stairs on the north end to find not only a wonderful view of the agora, but also, behind walls of glass, a long row of wooden shelves where myriad artifacts are stored. It was unbelievable to stand on the other side of the glass looking into the shadowed interior to see ancient black and red vases and kraters, kylixes and more. There were Mycenaean artifacts too, and all of it just sitting there silent witnesses to the ages gone past.

As we finished in the stoa and museum, we decided it was time to go. We made our way along a wall of broken monuments, displayed like ornaments in the garden of some antiquarian, each one with a story to tell of Athens’ past, each one whispering as I walked by.

I had to pull myself away from those voices, to tell them that I would see them again some day.

The day was wearing on, and there was more to do, more people to see before the end of my summer odyssey. But, I had to stand at the gates of the ancient Agora one more time and look out over the ruins of Athens’ history and up to the hopeful beacon of the Acropolis.

It is never easy to say goodbye to that ancient place, but I did so with a pang before turning and disappearing into the crowded market streets of Monastiraki and the Plaka, a part of me still wandering the Agora, haunted by history.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this short post on the agora of ancient Athens. If you did, you might also enjoy some previous posts on visits to Delphi, Delos, Tiryns, Epidaurus, Nemea, Eleusis, the temple of Apollo at Bassae, and Olympia.

Be sure to tune in next week as we step into the Hellenistic age with a guest post from historical fiction author Zenobia Neil.

Thank you for reading.

The World of The Dragon: Genesis – Part VII Sibling Rivalry: The Plot to Kill Commodus

Commodus was guilty of many unseemly deeds, and killed a great many people.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History)

Salvete, history-lovers!

Welcome back to The World of The Dragon: Genesis, the blog series about the research that went into our latest historical fantasy release set in the world of ancient Rome.

If you missed part six, about the Antonine Plague, you can read it HERE.

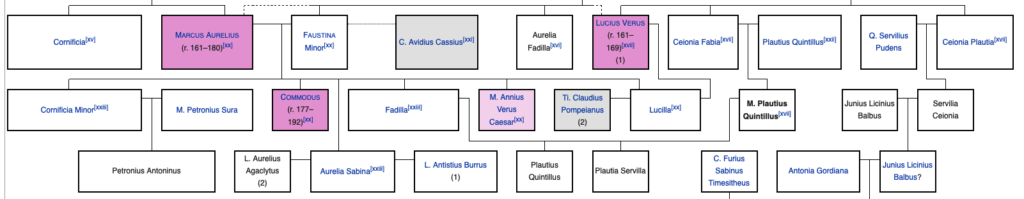

In this seventh and final part of the blog series, we’re going to be taking a brief look at the children of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor (‘the younger’), the reign of Emperor Commodus, and the plots against his life.

Was Commodus really the monster we imagine him to be, the megalomaniacal ruler we were confronted with in the movie Gladiator?

Read on to learn more.

Some people view the reigns of Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius as a sort of golden age of rulership in the Roman World. That was certainly true of Antoninus Pius, and perhaps less for Marcus Aurelius’ reign, but any sense of a golden age certainly ended with the accession of Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus who ruled as sole emperor from A.D. 180-192.

It was at this time that the Roman Empire perhaps took a turn for the worst. The time of the ‘five good emperors’ was at an end.

Because of popular culture, the two children of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor that most people are aware of are Commodus and his sister, Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla, or ‘Lucilla’. However, what many may not know is that Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor had thirteen children together over the period of their thirty-year marriage.

Most of these young Aurelii died young. There was the first-born, Domitia Faustina, who died at the age of five in A.D. 151. Then there were Titus Aelius Antoninus and Titus Aelius Aurelius who both died in 149. After the birth of Lucilla in 150, two more children were born, Annia Galeria Aurelia Faustina, and Tiberius Aelius Antoninus who died in 151 and 155, respectively, before another unknown child died in 157. Titus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus, Commodus’ twin brother, died at the age of four in 165, then Marcus Annius Verus Caesar passed at the age of seven in 169, followed by a young Hadrianus some time after that.

But there were other surviving siblings of Commodus and Lucilla who are not often mentioned in the history books, notably three more sisters: Annia Aurelia Fadilla (c. 159-211), Annia Cornificia Faustina Minor (160-212), and the youngest of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor’s children, Vibia Aurelia Sabina (170-216).

Obviously, infant mortality rates were very high in the ancient world, even for the upper classes. But, in hindsight, when one looks at the number of children Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor had, despite their mortality rates, one has to wonder if the emperor was indeed obsessed with having an blood-heir to the throne, despite the fact that he and his illustrious predecessors came to the throne through adoption.