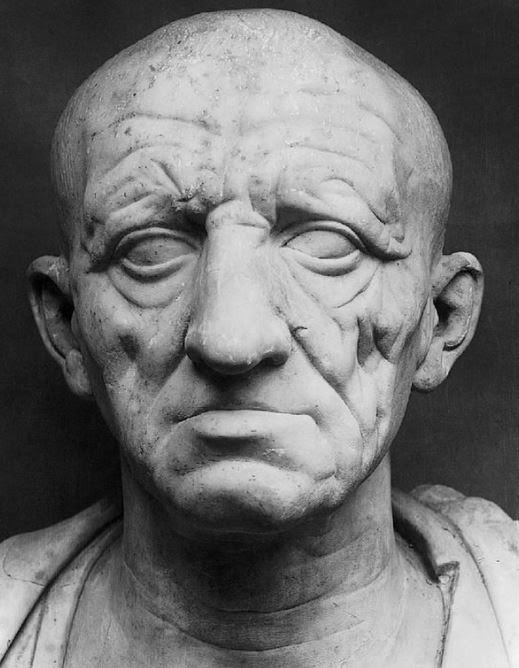

The World of The Dragon: Genesis – Part IV – The Evocati

Welcome back to The World of The Dragon: Genesis, the blog series in which we’re delving into the research behind our latest historical fantasy release, The Dragon: Genesis. If you haven’t downloaded your free copy of the book yet, you can do so HERE.

In Part III we looked at the division of the province of Dacia in the years after Trajan’s conquest. If you missed that, you can read it HERE.

Today, in Part IV, we’re going to be taking a brief look at a class of soldiers among the veterans of ancient Rome and how they often provided a strong back-bone in the ranks of Rome’s legions. We’re going to be looking at the Evocati.

In truth, primary and secondary sources do not have a great deal to say about the Evocati of ancient Rome. And yet, they were important, highly-respected members of society across the Empire.

So, what exactly was an evocatus?

The basic definition is that an evocatus was a retired Roman soldier who returned to duty after his completed term of service.

Some of you might remember this scene from the HBO hit series, ROME, in which Lucius Vorenus decides to go back into the service as an evocatus:

HBO’s ROME was a great series, but this scene seems more akin to the vigil kept by a newly-made knight during the Middle Ages. Truthfully, we don’t know how much, if any, ceremony was involved around becoming an evocatus. It may have been more of a clerical process, though religion was a big part of daily life.

What the scene above does, however, is portray the weight of the decision that re-enlisting might have had for a Roman who had already served for years in the legions.

From what we can gather, the Evocati gained more importance and respect during the Empire versus the Republic.

During the Roman Republic, the Evocati were ‘called-out’, which is where the meaning of the word comes from. This implies that they were compelled to return to service rather than given the choice. Calling out the Evocati might have been akin to instituting a draft in the Roman world.

During the Empire, however, veteran soldiers were invited to continue service as evocati, or they re-enlisted willingly.

There were two classes of evocati– the regular evocati of the legions, and the Evocati Augusti, the ‘Emperor’s Evocati’, who were former Praetorians who became evocati.

Before we go further, we should take a brief look at the veterans of ancient Rome.

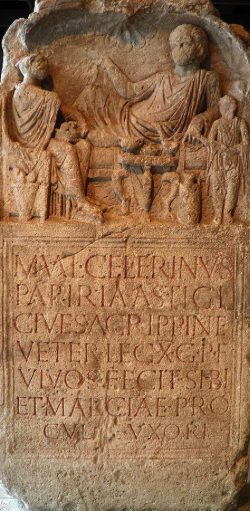

Firstly, how long a man served depended on which military force he was a part of. The lengths of time shift slight back and forth over the centuries, but generally, a legionary soldier served for 20 years, a Praetorian guardsman served or 16 years, and an auxiliary trooper served for about 26 years.

These terms of service might seem short to us today, especially when some people spend up to 35 years in a career, but it is important to keep in mind that the average age of mortality in the ancient world was much younger than today.

Twenty years spent in the legions was a much greater portion of a man’s life than we might think.

For veterans, the type of discharge one received was important, as it also determined the type life one might have enjoyed afterward. The discharge types were missio causaria (discharge through injury or illness), missio ignominiosa (dishonourable discharge), and honesta missio (honourable discharge).

If one completed the full term of service, and received an honourable discharge, then life was often pretty good. Veterans had legal status in ancient Rome, and were protected by laws granting them certain rights and immunities. They could go on to be local decurions (a sort of city councilor), and they could form collegia.

Veterans received land grants too, and it is said that Emperor Augustus settled about 300,000 veterans in colonies across the empire.

Upon being honourably discharged, veterans also received money, in addition to land. A legionary received 3000 denarii (later raised to 5000), and a Praetorian received 5000 denarii (later raised to 8250). Soldiers were also given back the savings they had been forced to put away during their time in the army. Under Hadrian, the land grants to veterans stopped, but they were still given fair financial recompense.

It seems that world leaders today could take their cue from the ancient Romans when it comes to taking care of veterans after their service is finished.

Veterans were leaders in coloniae across the Empire, and there was a peace and security present where veterans settled. This in turn attracted other civilians as the veterans also provided a skilled workforce locally. They were good for the economy too.

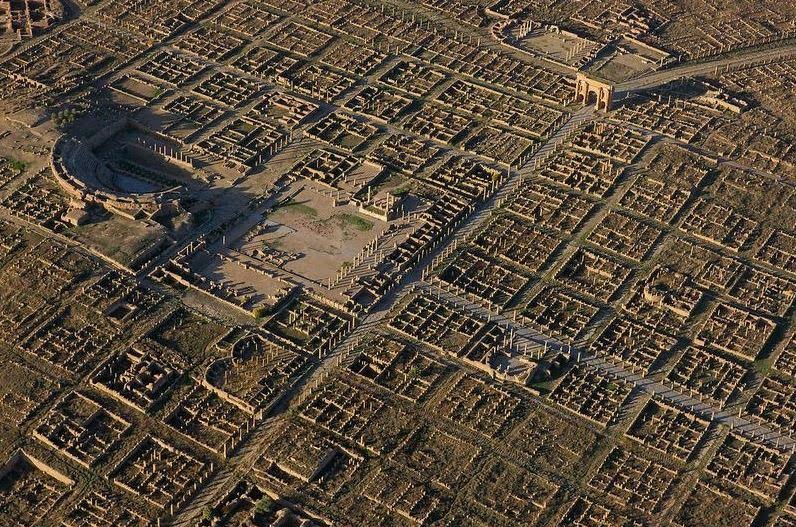

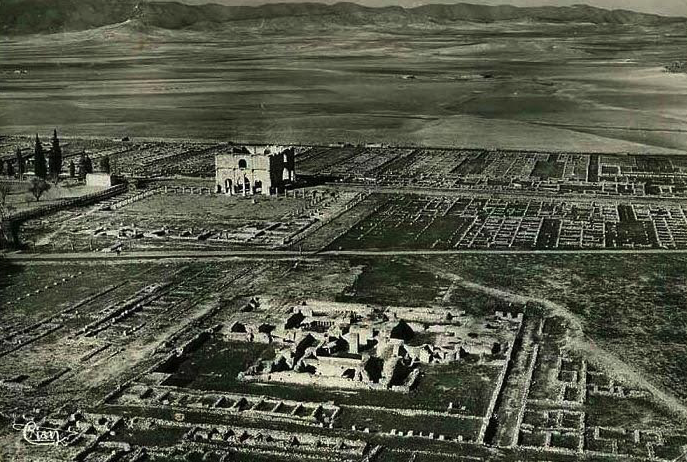

One example of a thriving veteran colonia on the edge of the Empire is Thamugadi, in Numidia, which was located a short distance from the legionary fortress of Lambaesis.

Aerial view of the colonia of Thamugadi, Numidia (North Africa), where veterans of the III Augustan Legion at Lambaesis were settled.

Not everyone was happy, however, with the presence of Roman veterans. Tacitus tells us of the tension between local Britons and their retired Roman conquerors:

And the humiliated Iceni feared still worse, now that they had been reduced to provincial status. So they rebelled. With them rose the Trinovantes and others. Servitude had not broken them, and they had secretly plotted together to become free again. They particularly hated the Roman ex-soldiers who had recently established a settlement at Camulodunum. The settlers drove the Trinovantes from their homes and land, and called them prisoners and slaves. The troops encouraged the settlers’ outrages, since their own way of behaving was the same – and they looked forward to similar license for themselves. (Tacitus, Annals XIV.33)

If most veterans who had been honourably discharged seemed to enjoy a good life (for them as Romans, that is), doing as they pleased on their granted lands, why might they have considered joining the ranks of the Evocati and going back to war?

Why were the Evocati even needed with so vast an empire?

Well, the Evocati were a sort of ready, trained militia that could be called upon in times of emergency, such as during the Boudiccan revolt of A.D. 60 when Governor Paulinus Suetonius called upon 2500 evocati to join the fighting. As Tacitus tell us, “the old battle-experienced soldiers longed to hurl their javelins. So Suetonius confidently gave the signal for battle.”

Evocati reported directly to the governor of a Roman province, so, in times of emergency, they could be used to reinforce the garrison.

Other reasons men might join the Evocati were the need for money if they had fallen on hard times, or even the need for purpose in life after the army. Just as today, it may not have been easy for a career soldier to reintegrate into civilian society, and so many might have welcomed the opportunity to go back to the ranks.

Lastly, men could be requested to re-enter service by the consul or their former commander. This happened frequently during civil wars. At the battle of Pharsalus, Pompey used 2000 evocati against Caesar, and later, Octavian enlisted 3000 evocati when going up against Marcus Antonius. In A.D. 67, Mucianus, the governor of Syria, is said to have enlisted 13,000 evocati to move against Emperor Vitellius.

I cannot give the exact strength…for the Evocati. Augustus was the first to employ this corps when he re-enlisted those troops who had served under Julius Caesar to fight against Antony, and he kept them in service afterward. To this day, they constitute a special corps and carry ceremonial rods as centurions do.(Cassius Dio, The Roman History 24)

When Augustus made the Evocati a sort of official class, as hinted at by Cassius Dio, was it just so that they could fight in times of emergency, or did they have some other purpose? What incentives were there for a veteran who had already served for years in the army to return to service?

It seems that when a man became an evocatus, he had special privileges. The Evocati did not go back to digging ditches and manning the front lines in battle. They were too valuable an asset for that.

Apart from fighting when the need arose, the Evocati fulfilled various other roles. They became instructors of aquilifers and other standard bearers, and physical trainers for the regular troops. Many evocati returned to the ranks to be officers or qualified and skilled administrators in the legions. Some joined the vigiles, Rome’s police and firefighting force. Others were army surveyors, architects, and quarter masters.

There were many roles an evocatus could fill in the legions.

More often, the higher-ranking and skilled evocati came from the Praetorian Guard, though sometimes from the regular legions. It could be a plum job.

Rome had a massive military force when you consider the regular legions, Praetorian Guard, and numerous auxiliary forces across the Empire. It has been estimated that about 250 men left each legion every year, and that about 15,000 soldiers retired from the Roman military annually.

That’s a huge number of trained troops to loose on a regular basis!

But Rome took care of it’s veterans for the most part. Men were rewarded accordingly for their years of service with money and lands. They could become valued and respected members of society, leaders in their own right. And even after their term as evocati, these veterans maintained that respect.

The Evocati of ancient Rome were, it seems, not only a skilled fighting force that could be called upon in times of need, but they were also a respected and important class in Roman society.

It may not have been a lavish lifestyle, but it does seem that life as an evocatus might have been better than most.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post about the Evocati in ancient Rome, and the research that went into creating one of the characters in The Dragon: Genesis.

If you have not already downloaded your FREE copy of The Dragon: Genesis, you can do so by CLICKING HERE.

Stay tuned for the next post in The World of The Dragon: Genesis when we will take a brief look at the joint rule of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Thank you for reading.

The World of The Dragon: Genesis – Part III – The Three Dacias

Welcome to the third part of this blog series about the world of The Dragon: Genesis. If you missed part two about the cursus honorum in ancient Rome, you can check it out HERE.

In Part III we are heading to what was once one of the most violent frontiers in the Roman Empire where, in the early second century A.D., one of the most famous of Rome’s military campaigns was waged. We’re heading into Dacia.

This is not, however, an in-depth study of the Roman campaign to conquer Dacia, but rather of the later division of the province, a move that heralded the importance of this province, and its resources, to Rome.

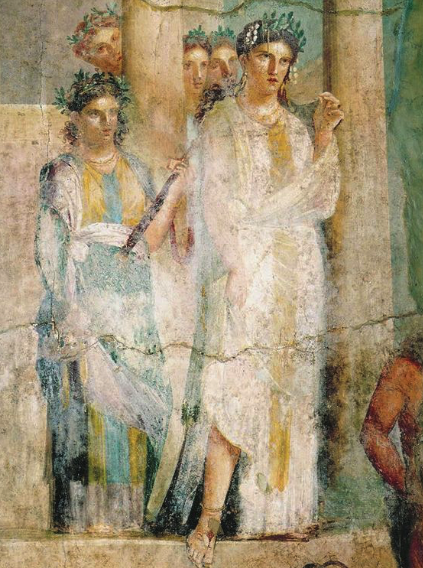

The ancient kingdom of Dacia, even now, conjures images of dark, mountainous forests where fearless warriors dwelled and worshiped strange gods. Today, the ancient lands of the Dacians comprise the region of modern Romania that strikes fear into the hearts of many: Transylvania.

But when the Romans waged war in Dacia, they were not fighting vampires or werewolves (read The Carpathian Interlude for that!). They were fighting a hearty race of warriors who would not be cowed by Rome’s might, and for years, the eyes of the Empire were set upon this area of Rome’s northern frontier.

Rome and Dacian had been at odds for decades before the Emperor Trajan and his legions marched across the Danube.

Truly, Dacian aggression had received a boost since the defeat of a Roman army at the battle of Histria (c. 62 B.C.), during the Mithridatic Wars, under the great Dacian King, Burebista. Many years later, there was a resurgence in Dacian pride under King Duras who, in A.D. 85 attacked the Roman province of Moesia. Rome was defeated again by the Dacians at the battle of Tapae in A.D. 88. After this, Rome strengthened the front, but it was widely suspected that Dacia would have to be dealt with.

Enter emperor Trajan. He is perhaps the reason we are so familiar with the name of Dacia.

Emperor Trajan invaded Dacia in two big campaigns in A.D. 101-102 and A.D. 105-106, not only to end Dacian aggression, but also to annex a new province for Rome that was extremely rich in resources.

After spending some time in Rome he [Trajan] made a campaign against the Dacians; for he took into account their past deeds and was grieved at the amount of money they were receiving annually, and he also observed that their power and their pride were increasing. Decebalus, learning of his advance, became frightened, since he well knew that on the former occasion it was not the Romans that he had conquered, but Domitian, whereas now he would be fighting against both Romans and Trajan, the emperor. (Cassius Dio; Roman History, Book LXVIII)

Trajan crossed the Danube into Dacia with 50,000 troops in A.D. 101. After the second battle of Tapae, in which the Dacian king, Decebalus, was defeated, the Romans pressed on toward the Dacian capital of Sarmizegethusa. The Dacian king was no fool, however, and he sought terms so that he could fight another day.

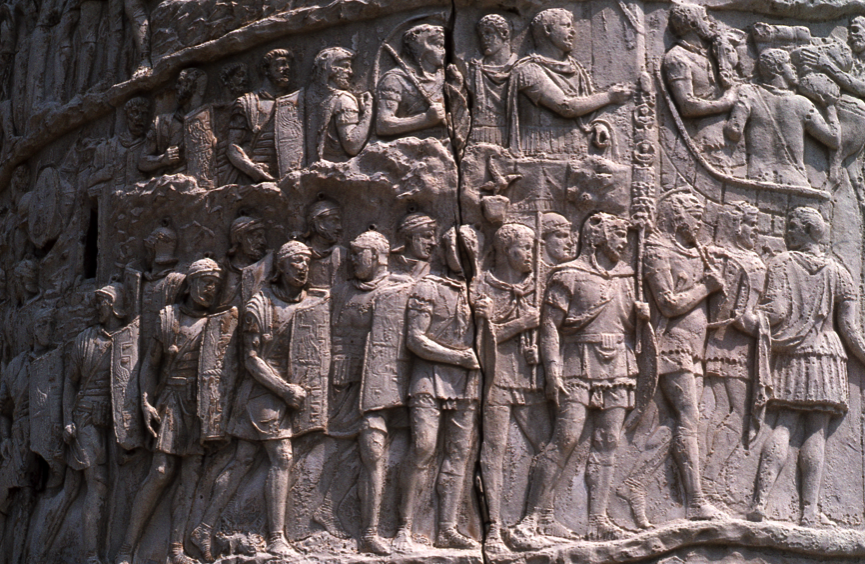

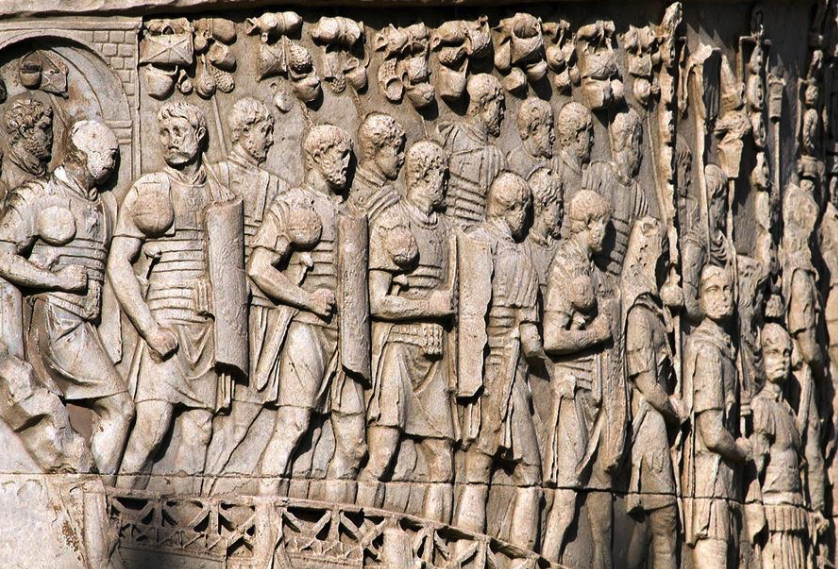

That day came in A.D. 105 when the Dacians attacked Roman outposts. This time, Emperor Trajan marched into Dacia and destroyed Sarmizegethusa. Decebalus committed suicide. The campaign is portrayed on the famous monument we now know as Trajan’s Column.

Despite some resistance under the Dacian king, Bicilis, Dacia became a new Roman province.

Trajan, having crossed the Ister by means of the bridge, conducted the war with safe prudence rather than with haste, and eventually, after a hard struggle, vanquished the Dacians. In the course of the campaign he himself performed many deeds of good generalship and bravery, and his troops ran many risks and displayed great prowess on his behalf. It was here that a certain horseman, after being carried, badly wounded, from the battle in the hope that he could be healed, when he found that he could not recover, rushed from his tent (for his injury had not yet reached his heart) and, taking his place once more in the line, perished after displaying great feats of valour. Decebalus, when his capital and all his territory had been occupied and he was himself in danger of being captured, committed suicide; and his head was brought to Rome. In this way Dacia became subject to the Romans, and Trajan founded cities there. The treasures of Decebalus were also discovered… (Cassius Dio; Roman History, Book LXVIII)

In conquering Dacia, Rome managed to add a resource-rich province to the empire. It was an extremely fertile land, perfect for agriculture, especially grain, which Rome always needed more of. The lands were ideally suited for livestock breeding, and the mountains yielded something which most civilizations hunger for: gold.

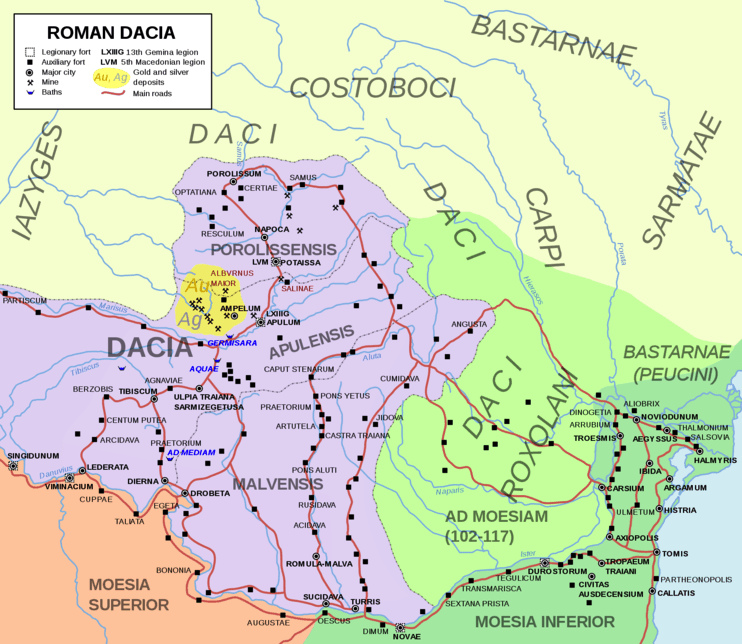

Over the years, Rome invested in massive mining operations in the province of Dacia and that, coupled with the other industries, meant that peace in Dacia would be highly profitable. Massive building projects were undertaken over the years with roads connecting military camps and ten cities, eight of which were coloniae where veteran troops were settled to begin new lives and families as part of the massive colonization project.

Dacia was developed into a new, urban province, and Rome was eager to protect this investment with a permanent garrison of about 35,000 troops which included two legions and up to forty auxiliary units.

At first, Rome had two administrative centres in Dacia. The first was Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegethusa, located just forty kilometres from the former Dacian capital of Sarmizegethusa Regia. This was the seat of the imperial procurator, Rome’s head finance officer in the province. The second main city at the time was Apulum. This was the seat of the military governor in Dacia, the greatest city in the province, and one of the largest along the entire Danube frontier. The XIII Gemina Legion was based there (the same legion that crossed the Rubicon with Caesar long before) within the walls of a fortress that covered 93 acres (37.5 hectares).

There was peace in Dacia after the conquest, but it was not without threat. Around the fringes of Rome’s new province, in the eastern Carpathian mountains and elsewhere, the ‘Free Dacians’, those tribes not under Rome’s direct control, posed a constant threat. That threat merited the massive garrison that was present in Roman-controlled Dacia. In the years to come, the Free Dacians would ally themselves with the powerful Sarmatians who would later put up a strong resistance to the later emperor, Marcus Aurelius.

During the reign of Emperor Hadrian (A.D. 117-138), Rome almost withdrew from Dacia because of problems with the Free Dacians, but also the issues that arose from administering the province. Changes were needed, and rather than pulling out of Dacia, Hadrian decided to make some adjustments.

Dacia was to be divided into two, with a second province of Dacia Porolissensis being created in western Transylvania. The high officials now included an imperial legate with consular powers, two legionary legates in charge of the two permanent legions, and the imperial procurator in change of finance.

In the novel, The Dragon: Genesis, however, the time period we are most concerned with is the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161). Hadrian’s adjustments made a difference but it became clear that more was needed in Dacia, and Antoninus Pius took advantage of the period of peace in Dacia to take action.

Massive repairs were made to the infrastructure of Dacia. All roads were repaired, fortresses were reinforced and updated to be more permanent, and the structures of the coloniae and other urban settlements were repaired. One such site was the great amphitheatre of Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegethusa.

In A.D. 158, the Dacians revolted, and this event brought about more change in the province. This brought about the creation of what has become known as the ‘Three Dacias’.

The emperor decided to add two more regions to the already existing Dacia Porolissensis by creating Dacia Apulensis, and Dacia Malvensis. Each zone was governed by an equestrian procurator, each of whom was responsible to the senatorial governor of the province.

The administrative capital of Dacia Porolissensis was Porolissum. This had been a military camp established by Trajan during the second invasion in A.D. 106. The purpose of this settlement was to defend the main route through the Carpathian Mountains. Five thousand auxiliaries were stationed there, and there were temples built to Jupiter, Nemesis, and Liber Pater.

The capital of Dacia Apulensis was Apulum, modern Alba Iulia. This is the setting for part of the novel, The Dragon: Genesis.

Apulum was the largest city in Roman Dacia and was the base of the XIII Gemina legion. It was also the seat of the military governor, which was not a coincidence, as the profitable goldmines of Dacia were located just to the west of Apulum and its legion.

The third of the new Dacias was Dacia Malvensis, the capital of which was Romula (also known as Malva) in the south. This settlement was a municipium at first, but later it became an official colonia under Septimius Severus (A.D. 193-211).

Romula had two forts and was the base for men from the VII Claudia, XXII Primigenia, as well as detachments of Syrian archers.

Peace however, even during the reign of Antoninus Pius, was fleeting.

In A.D. 161, upon the death of Antoninus Pius, there was trouble in Dacia once more.

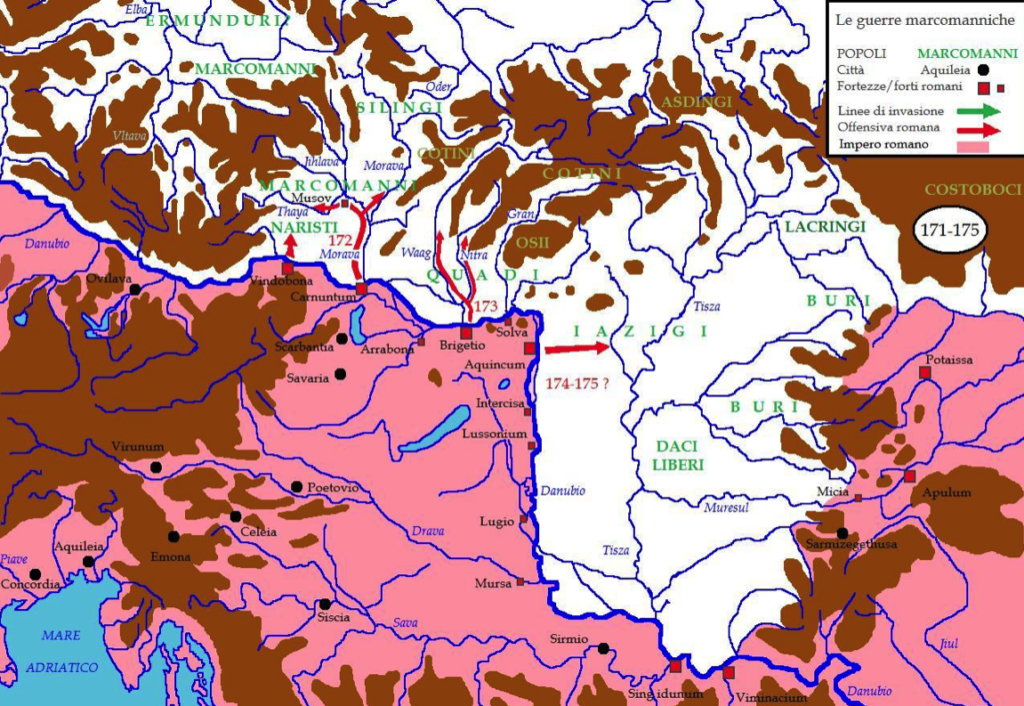

The alliance between the Free Dacians and their Sarmatian allies came to fruition during the reign of Marcus Aurelius.

The three Dacias were merged once again, and the mega province of Tres Daciae was created. The capital was moved to Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegethusa, and two full legions were on the alert – the XIII Gemina at Apulum, and the V Macedonica at Potaissa.

War had returned to Dacia and, unlike the long period of Pax Romana enjoyed by Antoninus Pius, it would occupy Marcus Aurelius in the region for most of his reign.

Much attention was given to Dacia over the years, especially to its administration. It was obvious that the province was of great importance to Rome, not only strategically, but more so economically.

There was, however, further conflict there through the reign of Emperor Commodus (sole emperor from A.D. 180-192).

During the reign of Septimius Severus, the Pax Romana was restored in Dacia and the frontiers strengthened. Severus’ laws allowing soldiers to marry helped them to integrate and form family bonds across the Empire, including in Dacia.

There is no doubt that the history of Rome’s presence in Dacia was long and varied, but there can be no doubt that Rome left its mark in that land, and it is a mark that can still be seen and felt to this day.

Be sure to stay tuned for the next part in The World of The Dragon: Genesis when we will take a look at the Evocati of ancient Rome.

Thank you for reading.

The World of The Dragon: Genesis – Part II – The Cursus Honorum in Ancient Rome

Salvete, history-lovers!

Welcome back to The World of The Dragon: Genesis, the blog series in which we’re taking a look at the research that went into our latest Eagles and Dragons series release.

In the previous post in this blog series we looked at the Antonine Wall, the construction and the history behind it. If you missed that post, you can check it out HERE.

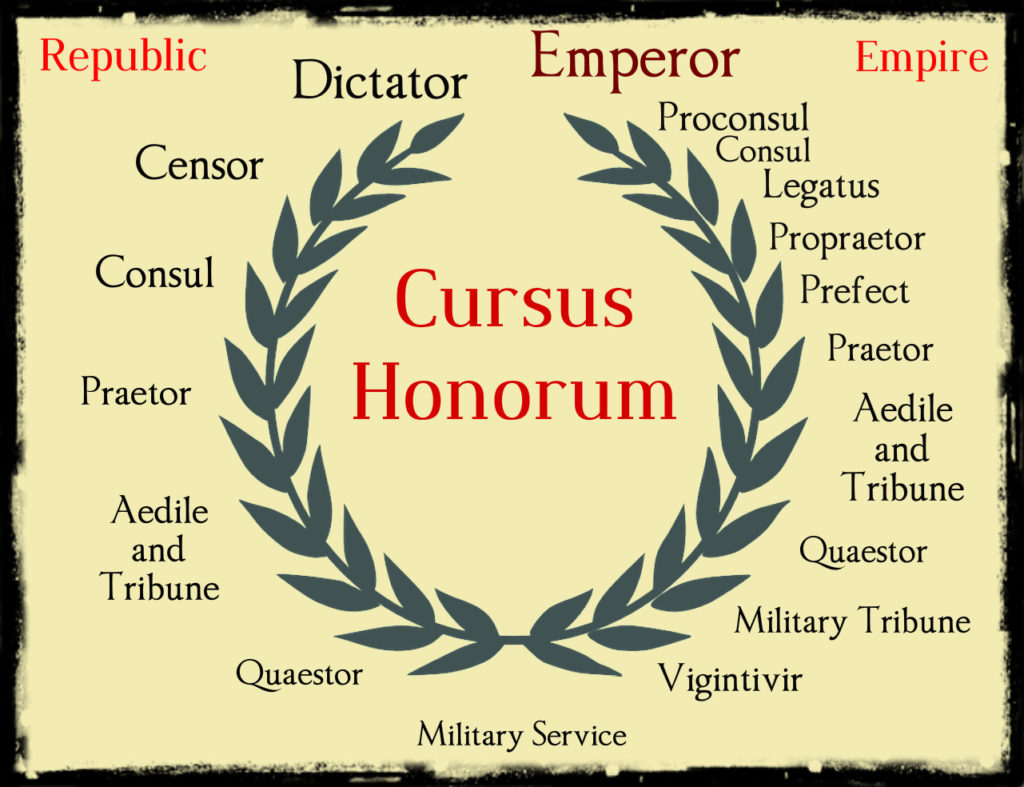

In Part II, we’re going to be taking a look at the prestigious career path sought by most men with political aspirations in ancient Rome – the cursus honorum.

What was the cursus honorum?

Literally, it meant ‘the course of honours’, and it referred to the sequence of official offices in the career of a Roman politician.

Late in the sixth century B.C., when Rome became a Republic, it was run (some might say ‘ruled’) by various magistrates who would form the members of the senate of Rome.

With the rise and rule of military commanders such as Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar, the magistracies of the Roman Republic became less effective, but they remained a prestigious goal for most.

From the third century B.C., there developed a specific track for a senatorial career – the cursus honorum.

In 180 B.C. a law was proposed by the tribune of the Plebs, Lucius Villius Annalis, which set down the rules and age limitations for the cursus honorum and, to an extent, perhaps sought to curb the ambitious young men of Rome.

In Tacitus’ Annals, we see reference to the law and the changes that had occurred within the cursus honorum:

With our ancestors, office had been the prize of merit, and all citizens who had confidence in their qualities could legitimately seek a magistracy; nor was there even a distinction of age, to preclude entrance upon a consulate or dictatorship in early youth. The quaestorship itself was instituted while the kings still reigned, as shown by the renewal of the curiate law by Lucius Brutus; and the power of selection remained with the consuls, until this office, with the rest, passed into the bestowal of the people. The first election, sixty-three years after the expulsion of the Tarquins, was that of Valerius Potitus and Aemilius Mamercus, as finance officials attached to the army in the field. Then, as their responsibilities grew, two were added to take duty at Rome; and before long, with Italy now contributory and revenues accruing from the provinces, the number was again doubled. Later still, by a law of Sulla, twenty were appointed with a view to supplementing the senate, to the members of which he had transferred the jurisdiction in the criminal courts; and, even when that jurisdiction had been reassumed by the knights, the quaestorship was still granted without fee, in accordance with the dignity of the candidates or by the indulgence of the electors, until by the proposition of Dolabella it was virtually put up to auction. (Tacitus, Annals, Book XI)

But the proposed law, the Lex Villia Annalis, was not without its opponents, and over time, more and more young men opposed the restrictions it imposed on the cursus honorum. Many disregarded its precepts and found ways around it. Some of the men who did this were Scipio Aemilianus, Gaius Marius, Pompey, and perhaps one of the most famous men to rise along the cursus honorum, Marcus Tullius Cicero, who is supposed to have achieved each level at the youngest possible age.

But what exactly did the cursus honorum entail? What was its purpose, and how did things work?

It is actually quite complex in the details, but we will now seek to look briefly at these questions to gain a better understanding.

General representation of the steps along the cursus honorum during the Republican and Imperial periods. (image: Eagles and Dragons Publishing)

The cursus honorum gave men with political aspirations a chance to work and prove themselves at various levels of government after their general military service. Because it evolved over time, there was a difference between the cursus honorum in the Republic versus the Principate (Imperial Age).

During the Roman Republic, the cursus honorum was a path open to men of the senatorial class. After one’s military service, the positions in order of ascendency were as follows:

Quaestor: twenty financial and administrative officials in charge of public records and the treasury (aerarium). They were also paymasters for the army, accompanying generals on campaign. This was a required post for those seeking to enter the Senate. The minimum age was 30 years.

Aedile: there were four patrician aediles who administered the temple of Ceres, and later were placed in charge of public buildings, archives, and later, public games. The minimum age was 37 years.

Tribune: ten tribunes were elected from the plebeian class, and their role early on was to protect this class from the patricians. They were directly responsible to the people’s assembly and had similar duties to other magistracies. They had a veto power in the city of Rome. The minimum age was 37 years.

Praetor: the praetors of Rome were the men who originally replaced the king. There were eight of these, and their role was to administer the law at Rome. They were, at first, the supreme civil judges. Later, they were to deal with legal cases with foreigners, and as Rome acquired more territories, more praetors were required. The minimum age was 40 years.

Consul: with the abolishment of the kings in 509 B.C., there were two magistrates at a time who were elected to this position. They had the duties of the king, but did not have supreme power. At first, they were only of the patrician class, but in 367 B.C., plebeians could stand for the office. Elections were held on the Ides of March (the 15th). The minimum age was 43.

Lastly, and not strictly a post required for the cursus honorum, the role of dictator was one that was granted by the Senate, through the consuls, during times of emergency. The dictator had supreme military and judicial authority, but other magistrates retained their offices during a dictatorship. It was usually granted for six months. After Julius Caesar’s murder on the Ides of March in 44 B.C., the office of dictator was abolished.

Ruins of the Basilica Julia (right of centre), one of the main public buildings, in the Forum Romanum

Now that we have looked briefly at the cursus honorum during the Republic, let us look at the course of honours during the Empire.

During the early imperial period, the cursus honorum was extended with a series of new posts being inserted between the offices of quaestor, aedile, praetor, and consul, which were retained. The role of senators was diminished, and they came to take on a more administrative role beneath the emperor. It is also important to note that the age requirements for posts were reduced, reflecting previous opposition to the old restrictions.

Here are the main positions along the cursus honorum during the Empire:

Vigintivir: there were twenty vigintiviri and these were minor magistrates who worked on various portfolios such as the mint for which perhaps only three of them would have charge of at a time. This position was the new stepping stone to get onto the cursus honorum path. The minimum age was 18 years.

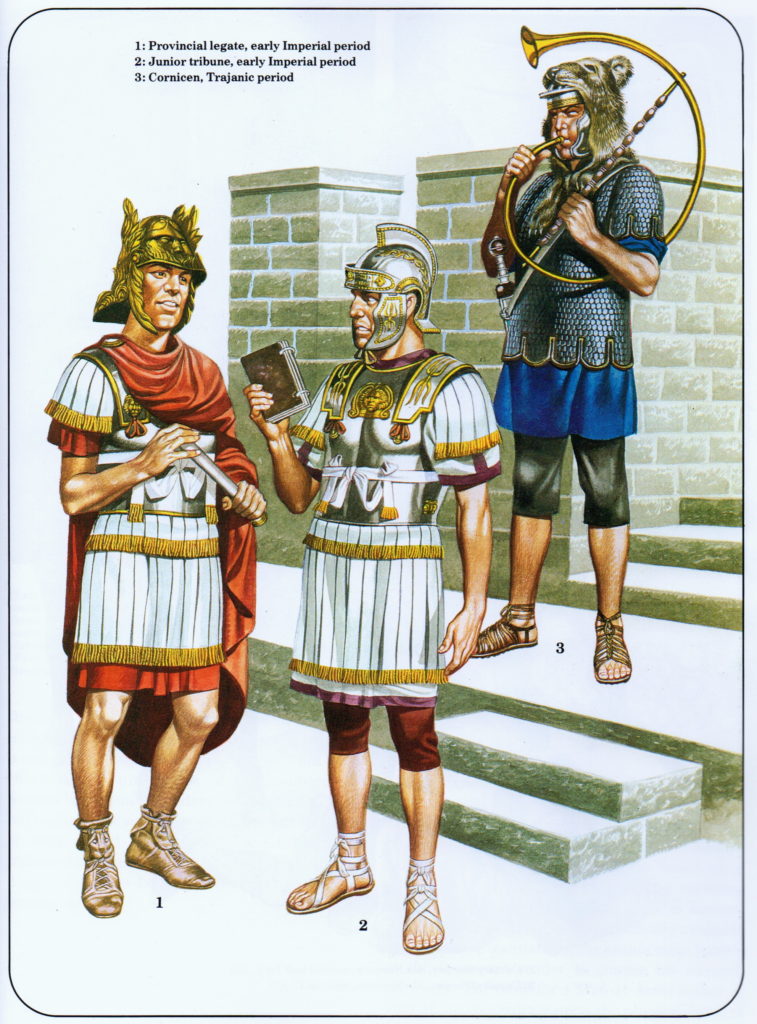

Tribunus Angusticlavius: the role of tribune during the Empire took on a more military role, with the emperors assuming the previous tribunician powers wielded by the tribunes of the Plebs during the Republic. This was one open to Equestrians (more on this class shortly), and there were five of these junior tribunes assigned to each Roman legion. The position remained until the fifth century A.D., and was another important step on the cursus honorum. The minimum age for a military tribune was 20 years.

Quaestor: during the Empire, the number of quaestors increased as the empire itself grew in size, and though their functions might have been slightly reduced, it was still a qualifying magistracy for entry to the Senate. Minimum age was 25 years.

Aedile: this position remained during the Empire, but it was not an essential part of the cursus honorum. However, as it served an important, elected, local role across the Empire’s domains, it provided the wealthy possessors of this position with an opportunity to gain publicity for their political careers and to accumulate voters. One of their roles was to stage expensive games for the people. And we know the Romans loved their games! The minimum age was 27.

Tribunus Laticlavius: this position was reserved for Patricians who served as the senior tribune in a Roman legion. These were not usually career soldiers, but rather would-be politicians on their way up the cursus honorum. The minimum age was 27 years.

Praetor: a praetorship was an important role during the Empire, and the duties of praetorswere actually increased as opposed to other positions. They were responsible for games and festivals, and propraetors (‘in place of praetors’) were chosen for military command as governors in some senatorial provinces. This was also one of the promagistracies during the Empire. A propraetorship extended the powers and time of one in that position. The minimum age was 30 years.

Praefectus: the role of prefect was an addition to the cursus honorum during the Empire. This was normally reserved for men of the Equestrian class, and served a variety of functions from being in charge of the grain supply (praefectus annonae) to the prefect of auxiliary forces in the army, or to the high position of Praetorian Prefect. Prefects gradually took over the roles of aediles. The minimum age was 30 years. However, the minimum age for the role of urban prefect was 32 years.

Legatus Legionis: there was great power to be had with the command of a legion, and the legionary legate was at the top of the chain of military command, beneath the emperor of course. Every legion across the empire had a commanding legate. The minimum age was 30 years.

Consul: during the Empire, the consuls lost all responsibility for military campaigns. It was more of an honorary position assigned (or assumed) by the emperors, and held for just two to four months. This meant that there could be up to twelve senators in this position in a given year. As an honourary position, the consuls were permitted to go around with a bodyguard of twelve lictors, and to wear a purple-bordered toga, a colour normally reserved for emperors. There were also proconsuls at this level. The minimum age was 32 years.

At this point, it is perhaps important to highlight the concepts of imperium and potestas. These were the types or classes of power held by some of the positions on the cursus honorum.

Imperium was supreme authority in matters of command in war, interpretation and execution of the law, as well as the passing of sentences of death as punishment. The positions that held imperium on the cursus honorum were consuls, praetors, the master of horse, and during the Republic, dictators. This was, perhaps, one of the great goals of the cursus honorum – to attain a position with imperium.

Potestas, on the other hand, was a general form of power held by all magistrates that allowed them to enforce the law according to the powers specific to their office.

There is no doubt that the cursus honorum could be a complicated route, especially with the changes, exceptions and dispensations over time between the Republic and the Empire. But, it remained an important tradition in Roman public life for the upper classes.

This was further complicated by the creation and inclusion of another class in Roman society – the Equestrian class.

In The Dragon: Genesis, one of the main characters seeking to climb the cursus honorum is of the equestrian class.

During the Republic, equestrians were below the senatorial class, but that changed over time and the two classes became more closely allied, so much so that the equestrians became the second level of the elite in Rome.

Emperor Augustus attempted to recast the equestrians as a military class, but this motion did not pass and, instead, around the year A.D. 69, equestrians became a sort of bureaucratic elite behind the senatorial governors of the provinces.

Because they posed less of a threat than the senatorial class, emperors like Commodus and Septimius Severus began to reward and rely more upon equestrians than ever before, even going so far as the grant them command of legions!

Equestrians were permitted to wear a narrow purple stripe on their togas, whereas men of the senatorial class wore a broad stripe.

For equestrians, the cursus honorum was a combination of military and administrative posts.

There were three commands for an equestrian officer in the military: a prefect of auxiliary infantry, a tribunus angusticlavius (on the cursus honorum), and a prefect of an auxiliary cavalry ala. The latter was one of the most prestigious positions available to equestrians. Equestrians could also become admiral of the navy, or a commander or prefect of the vigiles, Rome’s police and fire-fighting force.

As far as administrative positions for equestrians on the cursus honorum, they could be procurators in the provinces (such as a chief financial officer), or a prefect such as one in charge of the all-important grain supply.

As mentioned, perhaps the highest rank that could be granted to an equestrian during the Empire was one of the two positions of Prefect of the Praetorian Guard.

Whereas in the past, especially during the Republic, the path along the cursus honorum was clear, the later path for equestrians was not as stringent.

Though military service was expected, it came to be less of a requirement for equestrians and others.

Many did in fact seek to be career military officers without climbing the cursus honorum. The main character is The Dragon: Genesis is such a person.

However, those men with recognizable skills could receive special dispensation from military service, granted by the emperor, so that they could work in the law courts or imperial government. Emperor Hadrian did this, as did subsequent rulers.

Christopher Plummer as the Emperor Commodus flanked by lictors and the Praetorian Prefect (Fall of the Roman Empire – 1964)

The Roman Empire was vast, and there were any number of public positions up for grabs. Times changed, as did the requirements for public office. But Romans loved their traditions, and though the magistracies of the Republic were diminished in power over time, the cursus honorum was a path that was still respected and sought after.

The course of honours could be complex, and perhaps perilous, but then again, that it seemed to have been life in the world of Roman politics.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this second part in The World of The Dragon: Genesis.

The book is not for sale anywhere, but if you are interested in reading it, you can get a copy for FREE by clicking HERE, or by clicking on the book cover image above.

Stay tuned for Part III of The World of The Dragon: Genesis, when we will be looking at the creation of the three Dacias in the Roman Empire.

Thank you for reading.

The World of The Dragon: Genesis – Part I – The Antonine Wall

Welcome to Part I of this new blog series celebrating the release of the latest Eagles and Dragons series novel The Dragon: Genesis.

In this blog series, we’ll be sharing the research that went into the novel with you, looking at the history, settings, themes, and historical personages that are related to the story which takes place during the second century A.D.

When we think of the Roman Empire, what often comes to mind is the image of marching legions spreading out over the world. We also conjure images or memories of great ruins on the edges of Rome’s empire such as the massive amphitheater at El Jem in Tunisia, or the ruins of temples and other constructs that dot the European, Middle Eastern, and North African landscapes.

Roman frontiers were vast, stretching thousands of kilometers and encompassing many lands and peoples over time. These frontiers are perhaps what many think of when it comes to the Roman Empire, and none more so than Hadrian’s Wall, the great stone frontier fortification built by Emperor Hadrian in northern Britannia in the 120s A.D. It stretched 73 miles from modern Carlisle to Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and marked a decisive edge of the Roman Empire.

There was, however, another wall.

Approximately 100 miles to the north of Hadrian’s Wall, in modern Scotland, lie the somewhat less romantic, but highly significant, ruins of the Antonine Wall, another frontier of the Roman Empire, and an important cultural and heritage landscape today.

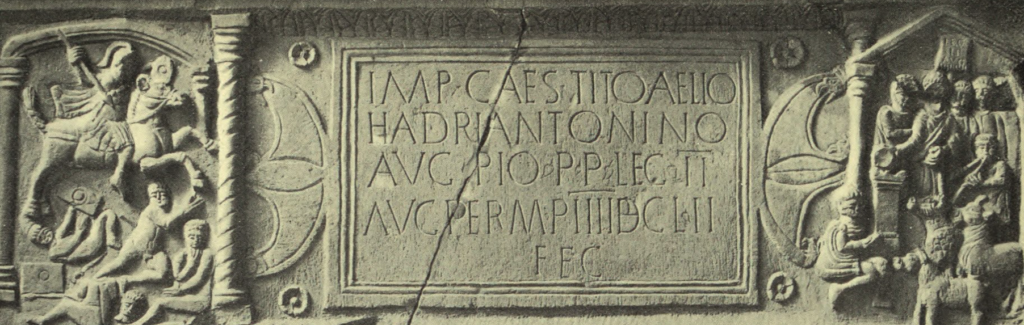

In the early 140s A.D., the emperor Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161) ordered a new frontier to be built in Caledonia. It was a massive building project, and the work was undertaken by the men of three legions: the II Augustan from Isca (Caerleon), the VI Victrix from Eburacum (York), and the XX Valeria Victrix from Deva (Chester). Until the forts and fortlets were constructed, the troops would have lived in tents in temporary camps, and among their numbers would have been specialists such as surveyors, masons, carpenters and many more.

At the outset, overall responsibility for the building project was given to the governor of Britannia at the time, Quintus Lollius Urbicus.

The purpose was, perhaps, two-fold: to attempt to push Rome’s permanent frontier father north, but also to hold back the warlike tribe (perhaps a confederation of tribes) we know as the Caledonii.

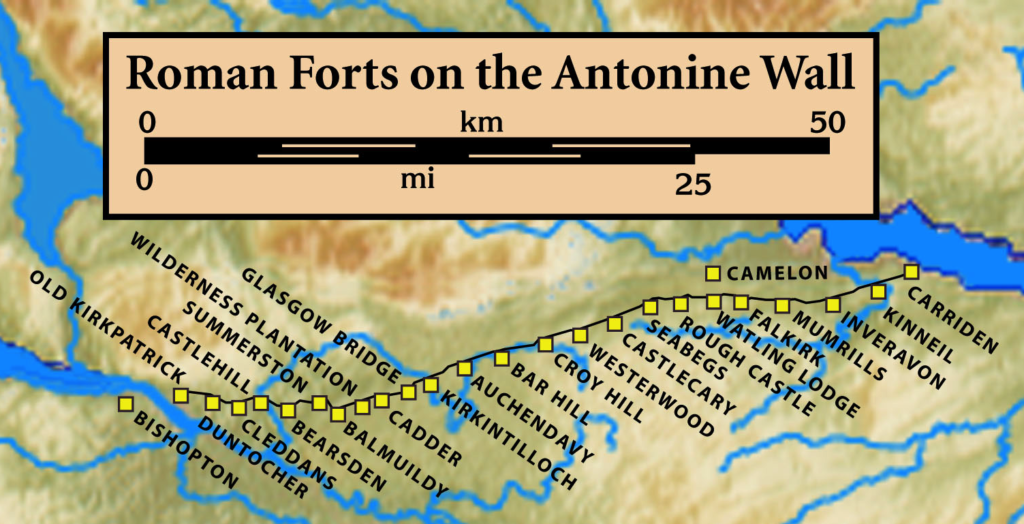

The Antonine Wall may be smaller in scale to Hadrian’s Wall, but it is still an imposing construction. It was 39 miles long, stretching from the Firth of Clyde in the West (near Glasgow) to the Firth of Forth in the East (near Edinburgh). It cinched the belt of Scotland.

But this was not just a wall! It was a manned frontier of the Roman Empire.

The Antonine Wall consisted of about seventeen forts and approximately 9 smaller fortlets every 2 miles, including two coastal forts at either end. The garrison of this frontier was in the range of 6000 to 7000 troops. This included legionaries, but the garrison was mainly comprised of auxiliary troops once the wall was complete.

Despite its importance, why isn’t the Antonine Wall as well-known as Hadrian’s Wall?

Part of the reason for this is that its ruins are less prominent. Less has survived.

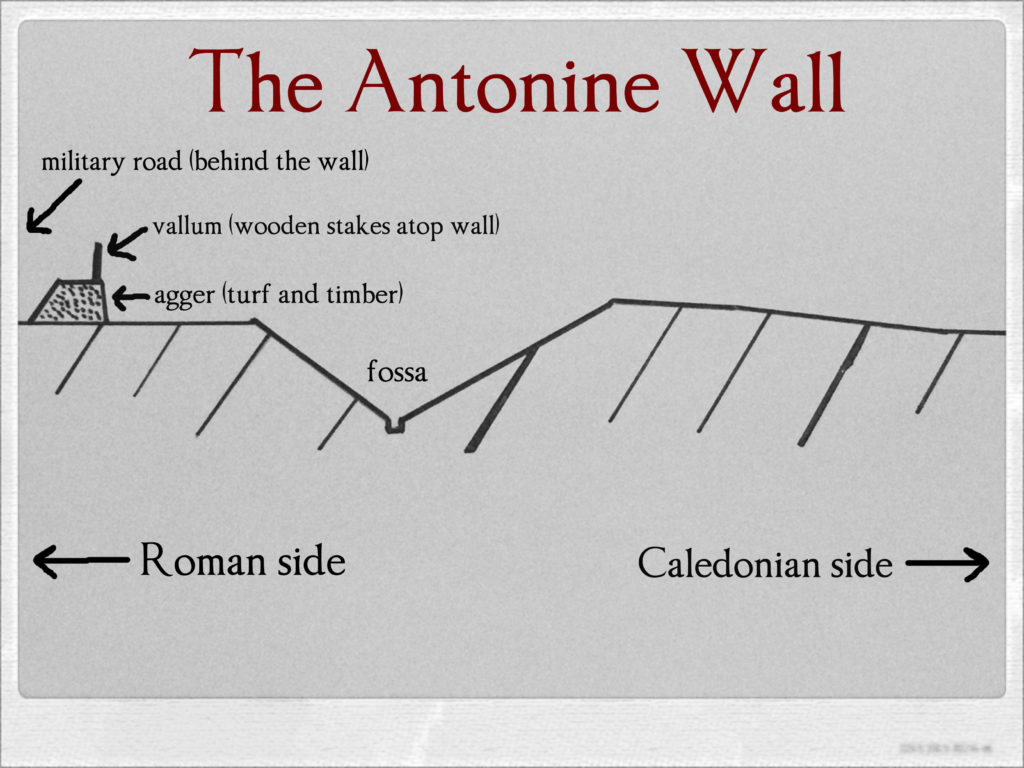

The Antonine Wall was not built of stone on the imposing scale of Hadrian’s Wall. It was a turf and timber wall built on a stone foundation. For this reason, today the remains mostly consist of a grassy embankment, 13 feet high, that was part of the ditch (fossa) located to the north the wall. The wall itself consisted of a turf embankment (agger) topped by a wooden battlement or barricade of sorts (vallum) behind the ditch. You can read more about the specifics of Roman defences HERE.

Unlike Hadrian’s Wall, which had ditches, or fossae, in front and behind, the Antonine Wall had but one fossa in front. It also had a military road running the length of the wall behind it so as to allow for quick, efficient movement of troops and supplies along the way, as well as the relaying of commands and news.

When completed, the Antonine Wall would have been an imposing defensive line in Caledonia. Interestingly, it was not the first such network.

There was a defensive line of forts from the Agricolan invasion of Caledonia in the first century A.D. that pre-dated both Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall. This frontier is known today as the Gask Ridge, and many of the forts along this first frontier were refortified during the Antonine period.

The Antonine Wall joined up with the Gask Ridge frontier roughly at the fort of Camelon, and together, the two frontiers further hemmed the Caledonii in on the highlands.

To read more about the Gask Ridge frontier, which is the setting for the novel Warriors of Epona, CLICK HERE.

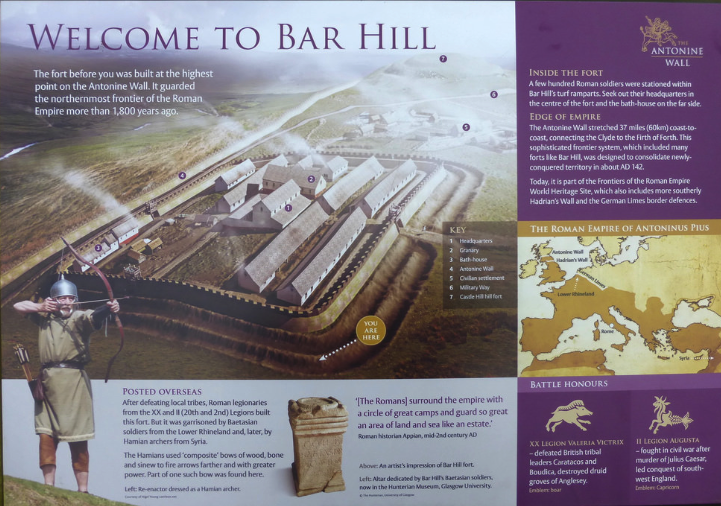

Signage at Bar Hill fort site showing reconstruction of the fort. Bar Hill fort was the highest point along the Antonine Wall.

The novel The Dragon: Genesis begins during construction on the Antonine Wall, specifically at the site of Bar Hill fort which was the highest point of the wall. This fort had commanding views from its vantage point, and it was one of the larger forts along the wall, complete with principia, or headquarters building. It is interesting to note that the fort here was not flush with the wall like some others, but rather was set back, just south of the military road.

The location of this fort made it the ideal place to start the novel.

It is perhaps an attestation to the resistance put up by the tribes of Caledonia that the Antonine Wall was abandoned in A.D. 162, just twenty years after construction began.

It lay in this state of abandonment until about A.D. 208 and the Severan invasion of Caledonia. At that time the Antonine Wall and many of the Gask Ridge frontier forts were re-garrisoned. To read more about the Romans in Scotland, CLICK HERE.

After the two phases of the massive Severan invasion of Caledonia, the Antonine Wall became silent once more, the frontier moving back again to Hadrian’s stone construction.

Today, you can visit the remains of the Antonine Wall on any number of walks to visit the locations of several of the forts listed on the map above, including the fort at Bar Hill. It really is an amazing landscape with many fascinating sites along the way. It’s no wonder that in 2008 it was officially given World Heritage Site status by UNESCO as part of the ‘Frontiers of the Roman Empire’.

To read a lot more about the Antonine Wall and the individual forts that are a part of it, be sure to check out the official website HERE.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this first part in The World of The Dragon: Genesis.

The book is not for sale anywhere, but if you are interested in reading it, you can get a copy for FREE by clicking HERE, or by clicking on the book cover image above.

Stay tuned for Part II of The World of The Dragon: Genesis, when we will be looking at the cursus honorum in ancient Rome.

Thank you for reading.

Cities for the Legions: A Brief look at the Roman Fortress

The Roman army. Those few words conjure images of blood and battle, marching legions spreading out across the ancient world. It was perhaps the most efficient military force in history, synonymous with skill, discipline, and invention.

Wherever we travel today in lands that were formerly part of the Roman Empire, we see the remains of that ancient civilization, and the remnants of Rome’s legions.

Few signs of ancient Rome’s built heritage compare with the military fortresses and forts that dot the landscape to this day. These ruins have been crucial in painting a picture of what life was like for the men of Rome’s legions, how they lived while on campaign.

There were, of course, many different types and sizes of camps and structures built by Rome’s armies across the Empire. There was the castrum (legionary fortress), the castellum (smaller camp or fort), the burgus (a small structure such as a tower, also known as a turris), signal stations and more.

In this blog, we’re going to take a brief look at that most important construction (other than roads!) of the Roman army: the legionary fortress.

In the early days of the Roman Republic, the Roman army was a field army that went out, fought actions, and then returned. But as Rome conquered more of its neighbours around the Mediterranean basin, and north and northwest into Europe, it gathered more territories that would require garrisons if they were to be held.

There were two varieties of the Roman army camp, or castrum– the temporary summer marching camp, or castra aestiva, and the more permanent winter camp, or castra hiberna.

Temporary camps were constructed at the end of every day by the men of a legion on the march, and then torn down the next day before setting out again so that the fort could not be used by the enemy. Roman legionaries, who came to be known as ‘Marius’ mules’, carried everything they needed on their backs, and that included two wooden stakes for fortifications, and a dolabra, or pick axe, which they used to shift earth for those fortifications.

Can you imagine marching twenty to twenty-five miles in one day and then having to dig ditches and create fortifications at the end of it? The men of the legions did this as a matter of routine!

The temporary camps were a sort of organized tent city where every eight-man tent (leather or canvas) for a contubernium was pitched in the same place at the end of every day. Efficiency and order were the name of the game, and the Romans were masters of both.

But the men of the legions, when at the outer reaches of Rome’s growing empire, needed warmer, more permanent quarters during the winter months outside of the campaigning season. Hence, the castra hiberna.

The requirement for permanent winter camps for every legion, in the provinces in which they were based, was issued by the emperor Augustus. The largest of these permanent camps could hold as many as two full legions! That’s over ten thousand men.

During the Julio-Claudian era, the walls of permanent camps were made of earth and wood, but from the Flavian era onward, walls were constructed of brick and stone, buttressed with earth. The structures within the permanent fortresses also evolved from their initial timber construction to more solid, long-lasting stone structures.

But how did the Romans decide where to put their camps, and how did they erect them? How were they defended? What did a legionary fortress or fort look like on the inside?

We’ll explore these questions next.

One simple formula for a camp is employed, which is adopted at all times in all places. (Polybius)

It would be a mistake to think that every legionary camp or base was exactly the same wherever you went in the Roman Empire. There was in fact a lot of variation due things like the terrain, the size of the force, and the preferences of the commander etc. But, there were certain features that were always the same, as is hinted at in the quote by Polybius above.

The first step would be to pick a suitable site for a fort that was both safe and strategic. A hill top was preferable, as was a site near to a waterway and water supply, as well as the road network if there was already one in place. Communication, hydration, and sanitation were essential!

Once a site was chosen, the ground was levelled by the troops (some stood on guard duty while most dug in). Generally, the first place to be marked out in a legionary fortress was the site of the principia, the headquarters building, at the intersection of the via Principalis and via Praetoria. This was marked with a white flag, and from here the rest of the fort’s grid was set up using a groma, a planning instrument with four plumb lines that helped to plan straight roads and to lay out the streets of the fort at perfect right angles.

Here is a short video (see minute 5:15) from historian Adam Hart Davis on how the groma was used for planning roads:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pUoSO5Rip7I

Using the groma, the intersections of the main streets of the fortress, the via Principalis and the via Praetoria, were laid out, thus allowing for the positioning of other buildings such as the tents or houses of the other officers, areas for cohorts, granaries etc.

Once the dimensions of the fort were set out, it was time to build what was perhaps the most important element of the fort: the walls.

When it came to linear defences, the Romans had everything covered. Actually, when it came to the defences of a fort, there were a few more elements besides the actual wall.

The fossa was a ditch in front of the rampart or wall of a Roman fort. There could be one or several fossae for a Roman fort, so this was variable. They could be up to twelve feet deep and three feet across, but these dimensions could also vary. Sometimes, sharpened stakes were also placed at the bottom, a little extra surprise for would-be attackers.

Behind the fossa or fossae of a fort were the vallum and agger, the raised embankments with sharpened stakes. So, after crossing the ditch of the fossa, an enemy would have to climb the embankment before tumbling down another ditch, after which he would be met with the wall of the fort.

The walls of camps varied in the materials used and the height they reached, but for the most part, the walls of permanent camps were eventually built in stone and could reach a height of ten to twelve feet, or up to four meters. During the Republican era, according to Polybius’ writings, forts tended to be square, but in the early Empire the preference was for irregular quadrilateral, and then a rectangular footprint. In the later Empire, any shape became possible, even circular!

Generally speaking, the walls of Roman forts were not very high, compared with their medieval equivalents, but the defences before those walls made it difficult for an enemy to breach the walls, especially under heavy fire from the legionaries on duty. There were not always towers on the walls of a Roman fort in the Republic and early Empire, but eventually, walls came to be toped by battlements called propugnaculae, and these were of different shapes and sizes.

Reconstructed, temporary defences at Alesia, site of Caesar’s defeat of the Gaulish forces led by Vercingetorix

Towers came into use too, with square ones being more common as they were quicker and easier to build, but later, after the reign of Marcus Aurelius, round and even pentagonal towers were built because of their superior strength. Sometimes, artillery was set atop the towers.

Because every Roman fort had four gates, these were also an important part of the fortress architecture, not least because they were a possible weak point. Early on, the gates were of a titulum or clavicula type, which means that an earthen wall was erected before the opening of the gate, directly in front (titulum) or on an angle (clavicula). However, from the time of Vespasian, gates were set into the walls themselves, sometimes with towers rising above them. These gates could allow up to ten men abreast to march through.

The last of the linear defences was the intervallum. This was a broad open space between the inside of the wall and the first buildings of the fort. In addition to this being a sort of buffer zone against enemy fire, it could also be used to store supplies and graze animals. However, the intervallum was eventually done away with and the buildings of the legionary base were built right up to the side of the interior walls of the fort.

So, what did one find inside the walls of a Roman legionary base?

A city for a legion.

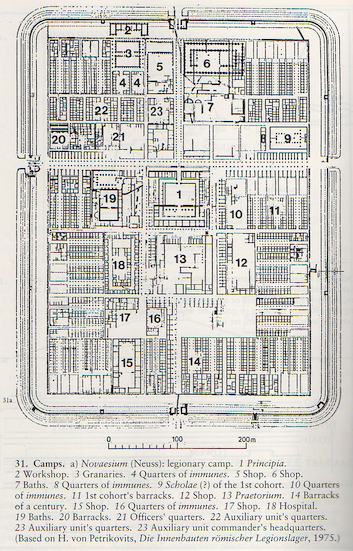

Full plan of the legionary fortress of Novaesium (Neuss), from The Imperial Roman Army by Yann Le Bohec

There were myriad buildings with as many purposes within the walls of a legionary fortress, and most of these would have been present, on a lesser scale, in smaller forts. At first, they would have been built in timber, and later, stone.

The most common structure was, of course, the barrack block. This was the long, rectangular building that housed the troops. For a legionary fortress, there would have been up to sixty-four barrack blocks. Each of these held a century of eighty men, and a contubernium of eight men would have shared one suite. Centurions had their own suite of rooms at the end of each block, possibly with their own lavatory. There might also have been a small mess room, and storage rooms.

A portion of the surviving barrack blocks of the fortress at Caerleon, Wales. This was the home of the II Augustan legion.

If you look at the previous blueprint of a fortress, you will see the barrack blocks in different sectors of the fortress.

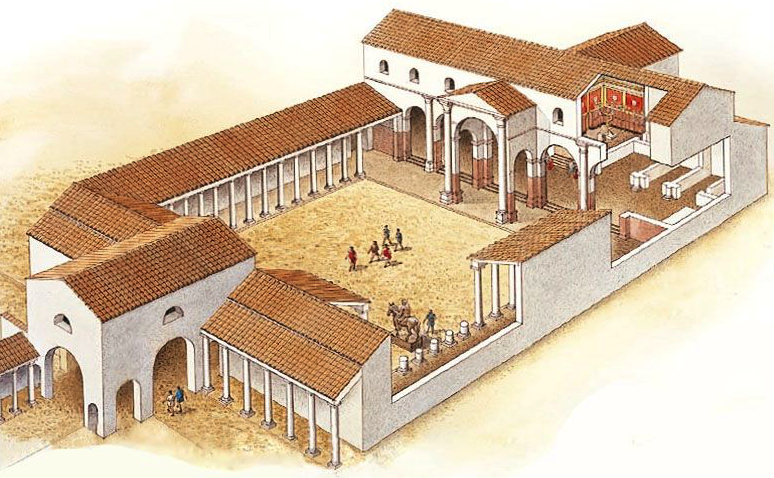

The heart of the legionary base, however, was the principia, or headquarters building at the centre of the fortress.

The principia of a fortress was one of the larger buildings because it included the offices of the legate, camp prefect, and the six tribunes assigned to every legion. There was also the armoury, and the tabularium legionis and tabularium principis, the records offices of the legion and its commanders. These would have been located around a central courtyard where offerings could be made and assemblies addressed.

But there was more to the principia than that.

The treasury was also located in the principia, as well as that all-important room known as the sacellum, the place where the sacred standards and imagines of the legion were kept along with the most important emblem of Rome’s legions, the aquila, or eagle.

The ruins of Lambaesis legionary fortress in Numidia (modern Algeria). You can see the large principia building toward the top left. What is unique about Lambaesis is that instead of a basilica there was an open air courtyard in front of the principia.

The treasury and the sacellum were often located within a covered basilica which was a part of the principia. In here, units could parade and officers could address the troops. This was especially useful in places like Britannia where the weather was often inclement.

Besides the principia of a fortress, the other important structure was the praetorium. This was the commanding officer’s, or legatus’, private house. The praetorium of a legionary fortress, and even of small forts, replicated the villas or town homes of wealthy Romans, complete with private baths, triclinium, several cubicula, a garden or peristylium, and more. These were rich accommodations befitting the senatorial status of a legionary legate.

Other officers too, such as the six tribunes (1 senatorial, and 5 equestrian) had private homes that were located along the via Principalis of the fortress. Though not as luxurious as the praetorium of the legate, the tribunes’ houses were also private and well-appointed, often with a smaller garden or peristylium.

But let us remember that this was pretty much a city that had to cater to upwards of five-thousand troops and various other workers. There was much more to a legionary fortress than offices, barracks, and officer accommodation.

There would also have been a large valetudinarium, a military hospital, that would have had enough space to accommodate up to ten percent of the garrison, whatever the size of the fortress or fort.

One would have found various fabricae, the workshops that made and repaired weapons and other armaments, bricks and roof tiles for building the fort and other projects nearby on which legionaries would have been employed.

Horrea, the granaries of a legionary base, were crucial to the legion’s survival, and these were carefully constructed to avoid damp by having them raised from the ground. The men needed to eat!

The men also needed to relax, and so that meant proper thermae, or baths, were needed within a fortress. Bathing to the Romans was, of course, not just about cleanliness, but also about socializing and relaxing. This was an important element of the fortress, for health and for morale. Along the theme of relaxing, there would also have been scholae, or clubhouses for various groups such as members of the centurionate, where men could gather with their peers to talk, drink, gamble and more.

And there were certainly stables in a fortress or fort too, whether for the officers’ horses, beasts of burden, or for any cavalry auxilia who were attached to the legion. It was important for the horses to be safely housed.

The structures noted above give you a sense of the massive scale of a legionary fortress, and the needs of a legion. There was, undoubtedly, some variation, depending on the size of the fort and its intended garrison, but most would have contained the structures noted above on some scale.

There are numerous remains of Roman fortresses and forts that you can visit today, whether they are remote, like the impressive remains of Ardoch, or one of the many dotting the line of Hadrian’s Wall, or whether their bones lie beneath our modern towns and cities, only to be glimpsed in select locations.

Vienna (Vindobona), Florence (Florentia), Chester (Deva), Caerleon (Isca Augusta), and York (Eburacum) are just a few examples of cities and towns that grew up around what were originally Roman legionary fortresses. Many of today’s most popular European cities were Roman army camps!

So, whether you are visiting the lands of the Sahara dessert in Algeria or Tunisia, or go as far north as the Gask Ridge in Scotland, you can be sure of that fact that, as you walk around taking photos and video, the Roman army was there before you.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief look at the Roman fortress. Please share this post with your fellow history-lovers and Romanophiles!

If you are interested in a virtual tour of a Roman fortress, check out the video below.

Thank you for reading.

Ancient Everyday – Education in Ancient Rome

It has to be admitted that learning does take something away – as a file takes something from a rough surface, or a whetstone from a blunt edge, or age from wine – but it takes away faults, and the work that has been polished by literary skills is diminished only in so far as it is improved… (Marcus Fabius Quintilianus)

Salvete, Romanophiles!

I think that most of us will agree that education is crucial to our quality of life and, if we are to take the Roman educator Quintilian’s word for it, learning only makes things better.

Education, however, is perhaps something that we take for granted in the West where most children have free access to a primary and secondary school education, and some beyond that. Today, education up to some level, is assumed.

But was it the same in ancient Rome?

In this new Ancient Everyday post, we’re going to take a very brief look at education in ancient Rome from the early Republican age on into the imperial period.

If you missed the previous two-part Ancient Everyday post on food and dining in ancient Rome, you can check that out by clicking HERE.

When I think of education in the ancient world, I have to admit that my first thoughts are of ancient Greece and the golden age of Athens which, let’s face it, created the foundations of education in the western world, especially a liberal arts education.

But even in ancient Greece, there were other systems. The Spartan agoge springs to mind, that educational machine of war that took young boys at 7 years of age and thrust them into a world of brutality and torture to create the best warriors of the ancient world.

When it comes to the Romans, however, education was more practical, a happier medium between philosophical discourses of Athens and the trials of Sparta’s agoge.

Throughout most of the Rome’s Republican age, homeschooling was how young boys, and sometimes girls, were educated. They were taught by members of their family, either the father and/or mother, or some other relative who may have been more qualified.

Boys were most often educated by their fathers in Republican Rome. The paterfamilias controlled everything, and made all the decisions about his children’s education, even whether or not they received one at all.

For another post on the role of the paterfamilias in Roman society, click HERE.

Cato thought it not right, as he tells us himself, that his son should be scolded by a slave, or have his ears tweaked when he was slow to learn, still less that he should be indebted to his slave for such a priceless thing as education. He was therefore himself not only the boy’s reading-teacher, but his tutor in law, and his athletic trainer, and he taught his son not merely to hurl the javelin and fight in armour and ride the horse, but also to box, to endure heat and cold, and to swim lustily through the eddies and billows of the Tiber. His History of Rome, as he tells us himself, he wrote out with his own hand and in large characters, that his son might have in his own home an aid to acquaintance with his country’s ancient traditions. (Plutarch, The Life of Cato the Elder)

From about the age of seven, Roman boys were trained by their fathers in the areas that were deemed most important to life as a Roman citizen: reading, writing, and weapons training. You can see from the quote above that Cato the Elder pursued this course with his own son.

Boys would also have accompanied their fathers on religious duties, as well as senatorial duties if they were from a senatorial family. Everything was geared toward an effective public life as a Roman citizen, and while boys were groomed for public life, girls were likewise groomed and trained in reading, writing, and arithmetic so as to be able to run an effective household.

At sixteen years of age, the boys of nobles were given a political apprenticeship, and then at seventeen, they spent the campaigning season with the army so as to learn the business of war, Rome’s bread and butter, so to speak.

This system of traditional homeschooling went on into the imperial age in some families, but it was in the third century B.C. that things changed and new ideas crept into the Roman educational system.

With the capture of the Greek colony of Tarentum in southern Italy in 272 B.C., and then the annexation of Sicily in 241 B.C., there was an influx of Greek prisoners of war and slaves into Roman society, and with them came Greek ideas.

Many of the Greeks who were brought into Roman society became teachers or private tutors.

Perhaps the most famous of this first wave of Greeks was Livius Andronicus (284-205 B.C.) who became a slave and tutor to his dominus’ children. He later was freed, and decided to stay in Rome where he is said to have become the first teacher of Greek education. He was also responsible for translating the Odyssey into Latin.

It was people like Andonicus who introduced the literary education to Rome, for prior to that, the focus in Roman education was more practical and martial.

But there remained differences between the Greek and Roman educational mindset for some time. For example, in the Greek educational system, music and athletics were of prime importance. These two areas were not taken seriously in Rome. To Greeks, music enriched the soul, but to Romans, music was perceived as a path to moral corruption.

I doubt that Cato the Elder was very musical!

Likewise, to the Greeks, the goal of athletic competition and training was to obtain a beautiful and healthy body, a noble goal in and of itself. In Rome, athletics were only seen as a way to maintain good soldiers who would fight for Rome.

Again, Romans were much more practical in their education and the goals of that education.

The study of literature, however, became more important in Rome as time went by, as it was seen to be beneficial in producing effective speakers. In a society where public life was so important, especially among the upper classes, this skill was crucial.

So, generally, what were the stages of the Roman educational system?

The first step was a sound moral education, and this began at home with fathers and mothers teaching their children (boys and girls) what Roman mores dictated were right and wrong, duties to family, to Rome, and to the gods themselves. In ancient Greece, community was central to moral education, but in Rome, it was all about family.

Formal early education began at age seven and lasted until age eleven. This included reading, writing and arithmetic taught by a litteratoror, in Greek, a paidagogus. Both boys and girls received this early education.

The rich tended to have private tutors for their children, but there were supposedly schools for the poor. This sort of school was known as a ludus litterarius. Because of the low wages paid to a litterator of the time, many such teachers also set up private schools of their own along the Greek tradition. These private schools did not have set locations, but rather moved around.

Secondary education in ancient Rome took place from twelve to fifteen years of age, and lessons were taught by a grammaticus.

The foci here were the literary subjects and the analysis and expression of ideas, and lessons were taught in both Greek and Latin. The purpose of the secondary education (more often of the upper classes) was for general education, but also to prepare for the all-important training in rhetoric. Many classical Greek texts were used, but as time passed and more Latin writers emerged, texts would have included the works of Ennius, Virgil and others.

Again, secondary education would have taken place in private, or in groups in various places.

The final major stage of education in ancient Rome was training in rhetoric.

Painting depicting Cicero speaking out against Cataline in the Senate – putting his rhetoric to good use!

Few studied rhetoric with a rhetor, but those who did tended to be boys over the age of sixteen years old with a view to public life and a long climb up the cursus honorem.

The goal of training in rhetoric was to perfect one’s political oratory and skill in debate so as to be ready for a senatorial career, or, during the imperial age when the senate lost influence, for a career as an advocate in the law courts.

After all of this, there was one possible final stage of education that was limited to a rare few from the elite of Rome’s upper classes, and that was the study of philosophy.

This required means, and perhaps leisure, but was seen as the pinnacle of education in philhellene circles. Students who sought an advanced education in philosophy usually went abroad to a centre of philosophy in Greece, such as one of the schools at Athens.

Most Romans did not pursue this course of learning, but those who did no doubt found their lives greatly enriched, and their speaking skills from the rostra of the forum expertly honed.

So, there you have it! A whirlwind look at the educational system of ancient Rome.

I hope you’ve found it informative and useful, and that the next time you go to a class of your own (or look back on one), remember that in our learning, we are standing on the shoulders of giants.

Thank you for reading.

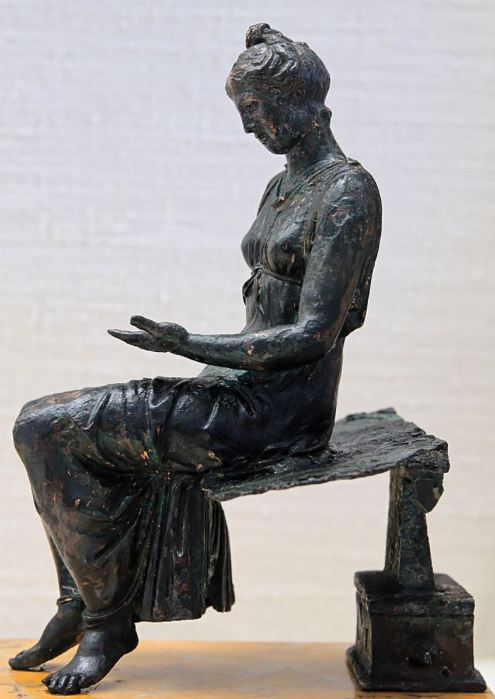

Roman Ghosts – Roots of Death and the Imperial Spectre

Salvete, History-lovers!

It’s been several months now since our last Roman Ghosts blog post and, seeing as we are in the dark days of winter, I thought it was a good time for a new one that you can read by the light of a warm fire.

If you missed the previous post about the ghostly accounts of Pliny the Younger, you can read it by CLICKING HERE.

I was doing some research on ghost sightings in the city of Rome when I came across this fascinating story about the only known haunting by a Roman emperor.

Who was this purple-robed spectre?

Why, it was none other than Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, otherwise known as Emperor Nero (A.D. 54-68).

There are numerous stories and much gossip about Emperor Nero, the last of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. It is said he believed he was an actor and artist, more than anything else. He allegedly fiddled his way through the burning of Rome, and subsequently blamed the Christian community for doing it. His torture of the Christians after that has become the stuff of horrible legend.

Another of the labels applied to this young megalomaniac was that of a ‘matricide’, for Nero was supposed to have made three attempts on the life of his overbearing mother, Agrippina the Younger. He tried drowning her, and crushing her in a planned ‘accident’, and when neither of those worked, he had his men slay her.

However, when the deed was done, Nero was haunted by the ghost of his mother for the rest of his days, so much so that he supposedly engaged the services of magicians and necromancers to help rid him of the Furies he believed to be harassing him, and to conjure the ghost of his mother so that he could ask her to leave him alone.

I guess it never was easy for a young Roman man to be completely rid of his mother!

Needless to say, Emperor Nero was a tortured soul.

But we are not here to determine whether the rumours about Nero were true or not. We are here to talk about the story of what happened after his death.

It seems that after he departed the mortal world, the shade of Nero lingered in Rome, and his is the only known imperial ghost on record.

You see, after his suicide, Nero was buried in the tomb of the Domitii Ahenobarbi, the family tomb at the foot of the Pincian hill. This was located near a grove of poplar trees in what is now the Borghese Gardens near Piazza del Popolo.

Legend has it that in the place where the tomb of Nero was located, adjacent to the Porta Flaminia, a sort of nut tree sprouted, and this tree was filled with black crows.

It was said that about the tree, or in it, Emperor Nero’s ghost continued his lavish feasts, except now he dined alongside demons and witches!

Over the centuries, Romans living in the area of the Pincian hill, near the Porta Flaminia, reported feelings of terror, possessions, beatings and injuries, inexplicable strangulations and killings. Hundreds of years later, in 1099, Nero’s ghost and his wicked dinner companions were still bothering the living.

Frightened Romans complained to Pope Pasquale II about the spectre and the terrible goings on around the tree at the foot of the Pincian hill. The pope stepped up and performed an exorcism in the area which ended with him striking the tree itself. When the pope did this, a series of loud screams apparently rent the air.

Pasquale II ordered the tree torn down then, and when it was removed, they found Nero’s tomb buried beneath it, among the tangled roots. The pope ordered the tomb and its contents to be thrown into the Tiber, and ordered a church built on the site, the altar of which was placed overtop of the spot where the tree had been.

In 1475, Pope Sixtus IV enlarged the church that Pasquale built, and it was re-consecrated as the Chiesa de Santa Maria di Popolo.

Apparently, the hauntings of Nero did stop after the original chapel was built in 1099, however, it is said that some people still report supernatural activity there.

Who knows for certain…

What we can be pretty sure of, if one believes in such things, is that in a city as ancient and populated as Rome, there were plenty of ghosts to go around. But there was only one imperial ghost…the ghost of Nero!

Guest Post: Archaeology and Living History: A Tasty Look at the Life of a Roman Re-enactor

Salvete, history lovers!

This week on the blog, I’m thrilled to invite archaeologist, Roman history re-enactor, and owner of Apicius Sauces Ltd., Rita Roberts, to share her story about her wonderful experiences with living history and how, through a bit of serendipity and creativity, she was able to launch a successful (and tasty!) enterprise with a little help from the famous gastronome of ancient Rome, Apicius.

Get ready for a fascinating look at the life of a Roman re-enactor. Be sure to read all the way to the end for an amazing recipe!

Take it away, Rita!

Living History

While working as an archaeologist at the Hereford and Worcestershire Archaeology Section in England, analyzing ancient pottery, I had the opportunity to travel around schools of the area. At this particular time, the Roman period was entered in the school curriculum. This meant that on occasion I was able to talk to the children in a class whose age varied between eight and twelve years old about the Roman pottery which I had been working on.

At this age children are very receptive and were eager to learn, besides the fact I had the original roman pots for them to see and handle. I was delighted at their reaction and soon realized that the living history, and hands on the objects, I was demonstrating was likely to be a real boost for education purposes.

Once teachers heard of my enterprise I was called to some of the schools regularly, especially to review the homework I gave the children once I had finished talking about the different types of Roman pottery. I was amazed as the teacher had made them draw the different shapes of the vessels.

One of the children wanted to know what kind of food was cooked, and in which vessel it was cooked in. It was from this little girl’s question I decided that on my next visit to a school, I would take along with me a Roman mortarium and mix the sauce which would have been served with chicken. Their teacher had already agreed on my return visit to demonstrate this to the class. Upon my arrival, and with the ingredients needed to make the sauce, I found the history teacher was waiting with the children who were all dressed up in Roman style outfits.

This seemed to make the children even more excited because after all, it was a living history lesson and they were eager for me to proceed. But first I needed to explain about the Roman cook Apicius.

Gaius Apicius lived during the reign of Emperor Tiberius in the 1stcentury A.D. The cookery books which he wrote were published some three hundred years later and are the main source of our knowledge of Roman food.

Apicius was able to buy a large selection of herbs and spices from Roman and Greek traders who travelled to the spice markets of South Asia. These were then offered for sale in the markets of Rome. Some of the sauces made by Apicius were flavoured with up to twelve different herbs and spices. Many spices such as pepper, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg and cloves came from India, Sri Lanka and China.

The highly flavoured sauces made by Apicius were often used to mask food which may have become stale or rancid because of over-storing. The most commonly-used seasoning was called liquamen. Apicius became a very wealthy man, but it is believed he committed suicide by poisoning himself. As a result of his buying so many expensive foods from every part of the known world, he realized that he had only about ten million sesterces left and he did not consider this enough to maintain his high standard of living.

Rita always displayed this Living History leaflet on the stall at each historical venue she attended.

Procedure for Making Apicius Sauce

Once I had the ingredients displayed on the table in front of the class, the children interacted by passing the herbs and taking turns in grinding them in a Roman mortarium, after which the liquids were added. The sauce was then ready for tasting. Mr Townsend, the history teacher, had the first sample. Then one by one the pupils very gingerly came forward to taste. There were many different comments such as ‘it’s quite nice really’, or ‘better than I expected’. Some of them did not like it at all. Another said it tasted a bit like curry.

However, Mr. Townsend was quite impressed, saying it had a unique flavour and that I should market it. I thought about this but knowing there would be a lot involved such as adhering to the Trading Standards and Health and Safety regulations. But first I thought about a trial period where I could sell my produce from a stall at The Woman’s Institute, and also The Woman’s Guild, which held events all year round. This proved successful, so after passing all exams needed for Trading Standards and Health and Safety Regulations, Apicius Sauces Ltd., was launched.

I had approached many museums, historical houses, English Heritage and The National Trust who all agreed to sell Apicius Sauces in their gift shops. We were also producing a variety of sauces from other historical times by request, ranging from the Medieval to the Stuart and Tudor times. Also, we were invited to join the Re-enactors Societies with the offer of a special stall with which to trade from. Below are some photographs taken at Kirby Hall.

Rita at her stall. The jars displayed in the dish were for people to sample. The taste surprise always led them to purchase not only for themselves, but to take home for friends who could not attend the re-enactment show.

Our product proved a positive success for almost fifteen years. We then retired to the island of Crete Greece.

The following is my recipe for ‘Sauce Apicius’ adapted for the modern kitchen and to be used with chicken. This recipe is for just one serving.

Ingredients for Sauce Apicius

A pinch each of – Pepper, cumin, thyme, fennel seeds, mint and rue.

A drop of asafoetida essence – obtained from a pharmacy and used sparingly

2 tablespoons of vinegar

4 oz of stoned dates

1 tablespoon of honey

1 tablespoon of olive oil

1 teaspoon of anchovy essence. This is to replace the roman liquamen or garum as anchovy was one of the ingredients used by the Roman cook to make the liquamen.

Method