Chariot Racing in Ancient Rome

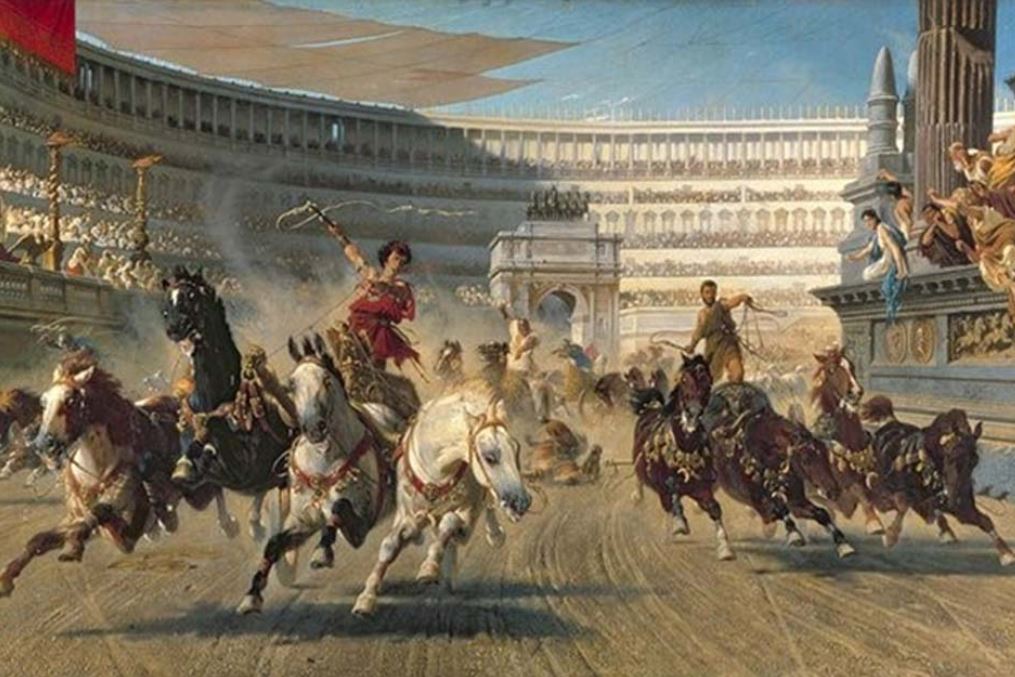

See you not, when in headlong contest the chariots have seized upon the plain, and stream in a torrent from the barrier, when the young drivers’ hopes are high, and throbbing fear drains each bounding heart? On they press with circling lash, bending forward to slacken rein; fiercely flies the glowing wheel. Now sinking low, now raised aloft, they seem to be borne through empty air and to soar skyward. No rest, not stay is there; but a cloud of yellow sand mounts aloft, and they are wet with the foam and the breath of those in pursuit: so strong is their love of renown, so dear is triumph. (Virgil, Georgics III-IV)

When we think of the raucous world of sport in ancient Rome, the images we conjure are most often of blood-soaked gladiatorial combat, or of chariot racing.

Today, we might think that gladiatorial combat was the most popular sport amongst the people of Rome, but in truth, nothing was more sensational than the chariot races put on in the great circus of Rome – the Circus Maximus.

In this post, we’re going to take a brief look at the circus itself, the charioteers, the horses, the fans, equipment, and what teams stood to win…and lose.

Their temple, dwelling, meeting-place, in fact the centre of all their hopes and desires, is the Circus Maximus. (Ammianus Marcellinus on Plebs and the Circus, XXVIII.4)

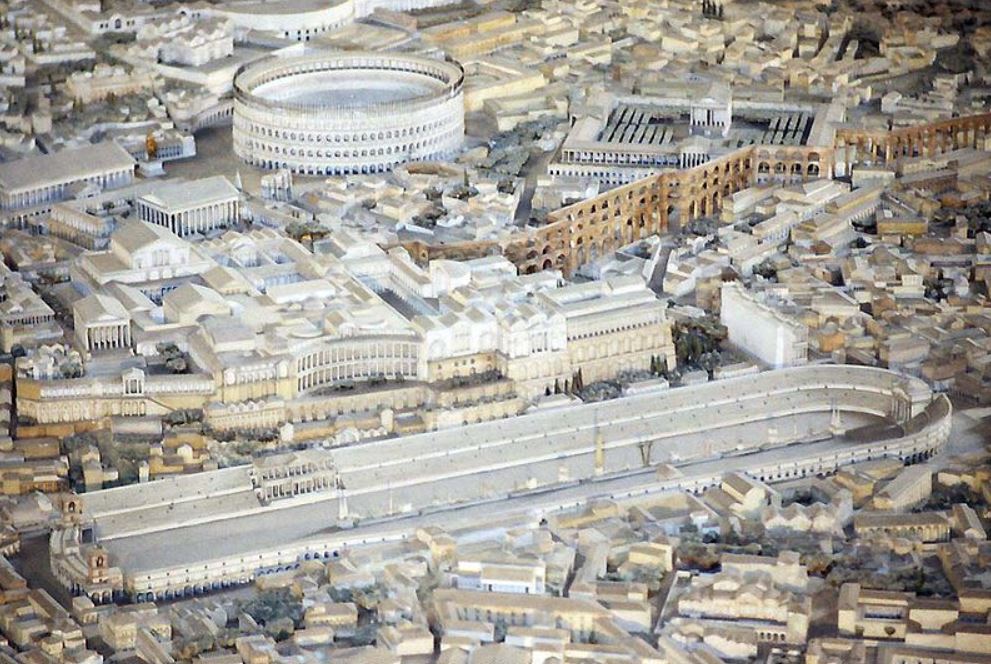

Chariot racing was an ancient sport handed down from the Greeks to the Etruscans and Romans early in the history of Rome, the races in the city of Rome being held in a dip in the land between the Palatine and Aventine Hills. Over time, the Circus Maximus was built upon by successive senates and emperors, making it the largest in the Roman world.

Rome’s great circus had an area of 45,000 square meters, making it twelve times larger than the Colosseum, and it could hold at least 150,000 spectators. With the addition of temporary wooden seating, the capacity was said to have reached 250,000!

The Circus Maximus was the largest and most expensive entertainment venue in Rome. Buildings had been added to it from the fourth century B.C. onward, going from wood to stone, and a major renovation was done in the first century B.C. Before the Colosseum was built, the Circus Maximus also hosted gladiatorial combats, wild animal hunts, and other games.

The Circus Maximus certainly owns its name, for by the time of Emperor Trajan, it was about 550-580 meters long, and about 80-125 meters wide. At the start of the track, there were twelve carceres, starting boxes, with ostia (gates) from which the teams would shoot out and charge the first 170 meters toward the central spina, which divided the course and which is what the teams raced around. The spina was 335 meters in length and 8 meters wide, and at each end of it were metae, the turning posts which the riders sped around. The spina was also ornamented with statues of the gods, towering palms, and obelisks from Rome’s campaigns in Egypt.

There were also large frames on the spina with mechanisms with suspended dolphins and eggs to count down the laps for a race. The total distance of a race of seven laps was about 5,200 meters over the packed earth and gravel track.

When it came to putting on games, or ludi as they were known, in the Circus Maximus, hundreds of staff were required in addition to the aurigae, the charioteers themselves. There were stable boys, grooms, cartwrights, saddlers, doctors, veterinarians, men at each of the starting gates (which were each six meters wide in Rome), men to clear the debris after crashes, lap counters, musicians, and even performers between races usually comprised of riders or acrobats.

That’s a lot of people to keep things running, but it was worth it to those who put on the games, for the people of Rome loved their chariot teams.

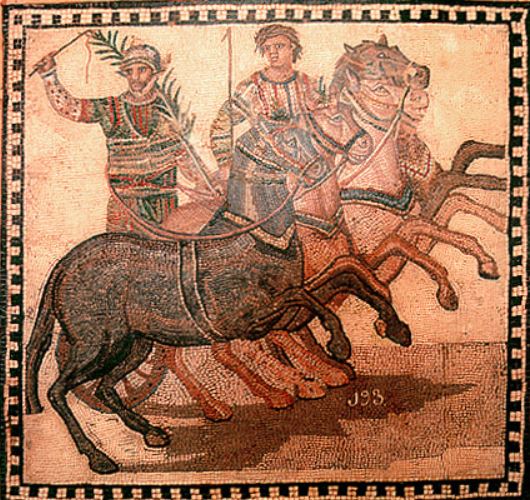

One might think that fans usually cheered for their favourite charioteers, but in truth, Romans were fans of their favourite factions, or factiones as they were known. There were four chariot factions in Rome: the Veneti (Blues), the Prasini (Greens), the Russati (Reds) and the Albati (Whites).

The four chariot factions of Rome were managed by the domini factionis, the ‘faction masters’ who were usually men of the Equestrian class. They would have sought out potential charioteers, made deals with others, and generally seen to the running of the faction and its success. The domini factionis were similar to the lanista of a gladiatorial school, or ludus.

In Rome, the factions had their headquarters, the stabula factionum, which contained accommodation and stables, on the Campus Martius, but their breeding grounds and training camps were located in the countryside.

People were wild for their factions, and there could be violence between the followers of each. During a race, each faction could enter either one, two, or three separate teams so that a full race could comprise up to twelve chariot teams running at a single time.

But who were the men who drove the factions to victory or defeat? Who were the charioteers of Rome?

O Rome, I am Scorpus, the glory of your noisy circus, the object of your applause, your short-lived favourite. The envious Lachesis, when she cut me off in my twenty-seventh year, accounted me, in judging by the number of my victories, to be an old man.

(Martial, Epigrammata, LIII. Epitaph of the charioteer Scorpus)

Outside of Rome, in the hippodromes of distant provinces, it was possible for individual owners to enter teams or even race themselves, but in Rome’s circus, it was the factions who entered the teams, and the professional charioteers, the aurigae, who raced for each faction.

The aurigae were usually slaves or freedmen, low on the status scale the same as gladiators, but they could achieve great fame and wealth.

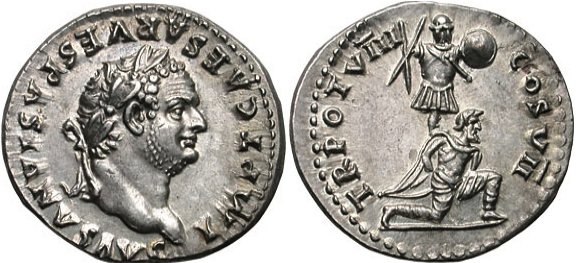

In his Epigrammata, the poet Martial tells us of a famed auriga named Scorpus who was one of the few charioteers to achieve the status of miliarius. The miliarii were those who had won over one thousand races – Scorpus was said to have won 2,048!

Ancient chariot racing in Rome was not dissimilar to modern sports. People were loyal to their faction, their ‘team’ so to speak, and charioteers, like pro sports players today, might be traded to or wooed by other factions. It was not uncommon for a charioteer to move factions several times before settling down in the latter half of his career.

Servants’ hands hold mouth and reins and with knotted cords force the twisted manes to hide themselves, and all the while they incite the steeds, eagerly cheering them with encouraging pats and instilling a rapturous frenzy. There behind the barriers chafe those beasts, pressing against the fastenings, while a vapoury blast comes forth between the wooden bars and even before the race the field they have not yet entered is filled with their panting breath. They push, they bustle, they drag, they struggle, they rage, they jump, they fear and are feared; never are their feet still, but restlessly they lash the hardened timber.

At last the herald with loud blare of trumpet calls forth the impatient teams and launches the fleet chariots into the field. (Sidonius Apollinaris, To Consentius)

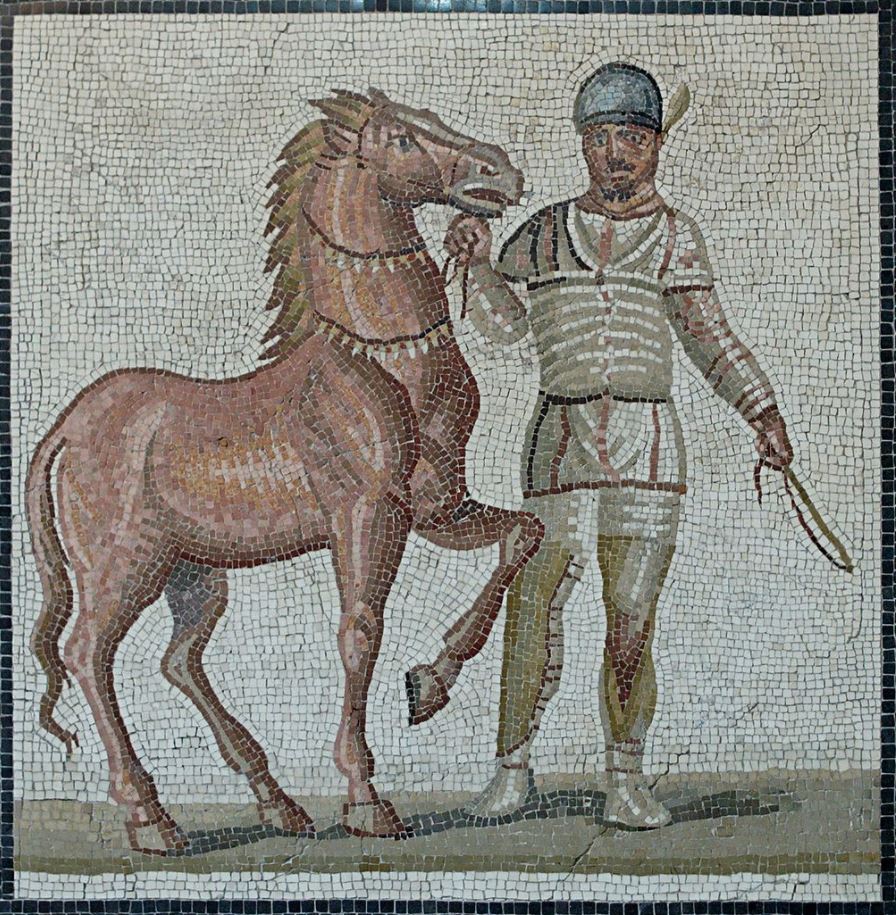

It wasn’t just the aurigae who achieved fame in the Circus Maximus. Horses too could be just as famous as their drivers, and oftentimes equine heroes were met with adoration.

Winning horses received palm branches, but also modii, which were measures of grain, with barley thrown into the mix. They were no doubt pampered back at the stabula factionum, and those horses who ran their factions to victory after victory enjoyed retirement in the countryside on a pension. They even received a burial with honour.

Race horses were bred and trained on private, and later imperial, stud farms, and the most successful breeds to race in the Circus Maximus were Lusitanos and Andalusian breeds from North Africa and Spain.

Though the horses were well-cared for by the factions, the racing was hard on their joints because of the tight turns of almost 180 degrees around the metae, and of course the great risk of injury.

Animal losses were high in the circus of Rome.

When it comes to the chariots and equipment used for the sport of chariot racing in ancient Rome, the movies have often been misleading.

In movies like Ben Hur (pictured above) the chariots are massive, some with long blades sticking out of the wheels. The chariots used in the movie made for some exciting film making and a great scene, but they were not at all accurate as far as what was really used.

Statue of a Roman biga (two-horse chariot) found in the Tiber. Note how much smaller the chariots actually were compared to what we see in the movies

Roman racing chariots, which were adapted from the ancient Greek and Etruscan chariots, were light-weight affairs, consisting of a slight wooden frame bound with strips of leather or linen, and small wheels with 6-8 spokes.

The most common chariot was the quadriga, a four-horse chariot from ancient Greece. The other commonly-used chariot was the biga, a Roman two-horse chariot. These two types were what were raced most often in the Circus Maximus in Rome. However, there were said to have been six-horse chariots (seiugae), eight-horse chariots (octoviugae), and even a ten-horse chariot (decemiugae).

Unfortunately, no remains of an imperial Roman chariot have been found, so we are forced to rely on artwork for an idea of their appearance. However, the tombs of Etruscan nobility have yielded some two-hundred and fifty examples of chariots.

In ancient Greece, charioteers wore only a long chiton with a belt when they raced, but Roman and Etruscan aurigae wore a short chiton, a protective skull cap or leather helm, and a wide leather belt composed of many straps. They also wore linen or leather wrappings on their legs and carried a curved dagger on them.

Why did they carry a dagger?

Well, it wasn’t to attack each other during the races. The reason for the dagger was that unlike Greek charioteers who held the reins in their hands, Roman charioteers wrapped the reins around their waists in order to use their whole body to steer the team and have one hand completely free for the whip.

If they ever got into a naufragia, a ‘shipwreck’ as chariot accidents were called, the dagger was supposed to be used to cut oneself free of the reins that were wrapped about you. It certainly was a risk when driving a team of four horses up to 75 kms per hour while trying to cut off your opponents going into the turns and so on.

One thing’s for sure, Roman chariot racing was extremely dangerous, though perhaps not as hazardous to one’s life as gladiatorial combat.

Games, or ludi, were the highlight of the Roman calendar, and chariot racing in the Circus Maximus was always the main event. During imperial games, there were usually up to twenty-four races per day at Rome, and that could include up to 1,152 horses.

This was always an event on a titanic scale, and the people of Rome loved it!

People were fanatical about their factions, and the charioteers who risked their lives in the Circus Maximus must have felt near to gods when the adoration of the crowd shone full upon their faces.

Apart from the traditional victory palm, winning charioteers and their factions could receive massive fortunes for their success.

In Rome, prizes ranged from 15,000 to 60,000 sestercii per race! That’s far more than the annual pay for a legionary soldier who received about 900 sestercii per year during the early Empire.

One charioteer by the name of Gaius Appuleius Diocles was said to have won almost 1,500 races and when he retired at the age of forty-two, he had a fortune of 35.5 million sestercii!

I guess some things don’t change, as the salary of military personnel today is far outstripped by that of the average sports star.

It seems that those who are destined entertain us, whether a modern sports star or an ancient charioteer in the circus of Rome, are going to be raised above the average person in society. Victory brings great reward, it seems, and ancient Rome was no different in that respect.

Bread and circuses!

There’s a reason Juvenal wrote those words back in the first century A.D.

Thank you for reading

For those of you who are interested, the Timeline documentary below talks about the history and technical specs of ancient Roman chariot racing while training four modern equestrian experts to become charioteers and then race each other. You might want to check this out!

Roman Ghosts: Shades in Eburacum

Greetings history lovers!

Welcome to the first post in what we hope will be an ongoing blog series called Roman Ghosts.

We all love a good ghost story, and as everyone reading this presumably loves ancient history, we thought it would be fun to combine the two.

In this series (which will be posted sporadically as we discover more Roman ghost stories) we will not be setting out to prove or disprove anything. We’re not scientists, myth busters, or ghost hunters.

With the Roman Ghosts series, we’re interested in the stories and sightings themselves. At the end of this inaugural post, you’ll see how you can help and be a part of this.

The first Roman ghost story we’re going to look at is one that you may be familiar with.

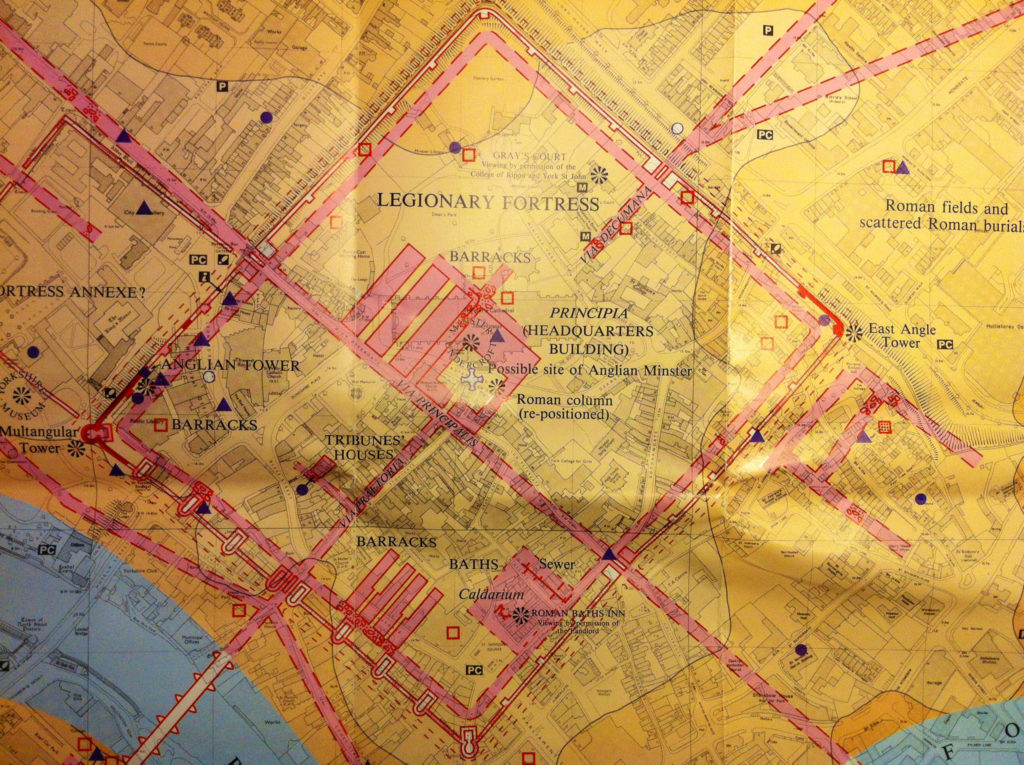

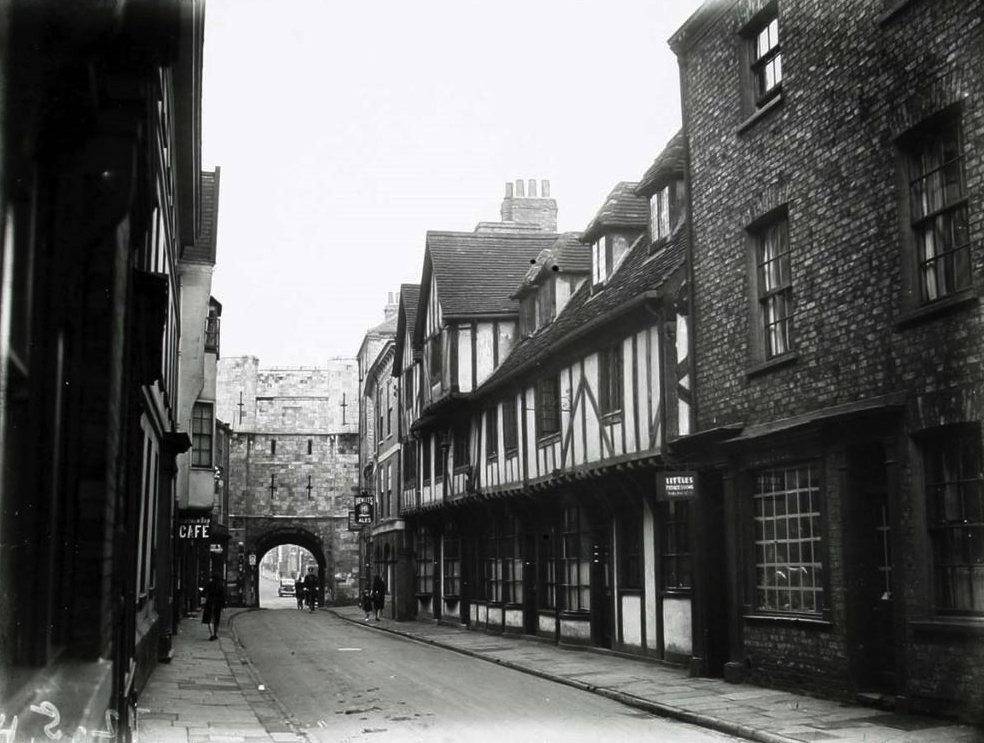

In the province of Britannia, one of the principal legionary bases was that of Eburacum (also ‘Eboracum’), or modern York.

York is a beautiful city today with some amazing medieval remains, York Minster, the Shambles, the Yorvik Viking Centre and more. I’ve been to York several times and enjoyed myself immensely each time.

The Roman ruins of York are less visible than the grand medieval remnants such as the walls and Petergate, but they are there.

In fact, the oldest part of York today was built pretty much on top of the original legionary base.

Today’s High Petergate runs from the northwest to southwest along the line of the orginal Via Principalis of the legionary base, and York Minster was built on top of the Principia, the headquarters building of the legion. Among the more visible Roman ruins is the multi-angular tower located to the southwest of Petergate itself.

If you know where to look in York, there are indeed Roman remains to be seen, including beneath York Minster, and, one of my favourite places, beneath the Roman Bath pub where you can visit the remains of the fortress’ baths after a pint and a good meal.

York, or Eburacum, was famous for its connections with a couple emperors, including Constantine the Great, whose statue sits outside the minster, and before him our own Septimius Severus. In fact, I’ve set part of Warriors of Epona, and the upcoming Isle of the Blessed in Eburacum during Severus’ time there.

But we’re here to talk about ghosts, aren’t we?

On my first visit to York I took a walking tour. Our guide told us many things, but what stuck with me the most from that tour was the tale of a young plumber who, in 1953, says he saw Roman soldiers come out of a wall where he was working in the cellar of the Treasurer’s House.

There are many theories about places holding memory, and about how the spirits of the departed may linger in a place where they spent time.

Eburacum was home to two British legions for over 300 years! First, it was garrisoned by the IXth Hispana Legion from about A.D. 71-121. This is the famous ninth legion that some believe went missing after a campaign in Caledonia, and which was made famous in the novel The Eagle of the Ninth by Rosemary Sutcliff. After that legion vanished (or was assigned to another part of the Empire), Eburacum was garrisoned by the VI Victrix Legion which remained there for close to three hundred years and may have been the last legion to leave Britannia when Rome pulled out.

Needless to say, a few generations of Romans called Eburacum ‘home’.

The Treasurer’s House is located just to the north of the minster, near the Roman Via Decumana of the old legionary base. This is where, in 1953, eighteen-year-old Harry Martindale, an apprentice plumber, first saw a troop of about twenty ghostly Roman soldiers.

According to Martindale, he was working alone in the cellar of the Treasurer’s House, the lowest point of which was the original Roman road, possibly the Via Decumana itself.

While he was on a ladder, he heard an odd sound, as if some sort of music was playing, a horn of some sort, perhaps a cornu. He looked down from his ladder and there saw the top of a helmet come out of the solid wall he was working at.

He stumbled down and fell into a corner to watch in terror as several legionaries, as well as a mounted cavalryman, marched out of the wall, along the road, and then disappeared into an opposite wall!

The strange, and terrifying thing is that Martindale did not say they were cloudy apparitions such as we might expect ghosts to be. Rather, as he sat on the floor watching them, he noticed that they looked as real as you or I. He could see the details of their armour, weapons, clothing, and even the stubble upon their faces!

He also noticed that when they came out of the wall, they were only visible from the knees up, that is, until they stepped onto the Roman road itself and their feet finally became visible.

Now, if that doesn’t send a chill down your spine, I don’t know what will!

Harry described all he had seen to historians and they confirmed that the details he described, of the armour and weapons etc. were genuine and accurate, and may have been Roman auxiliary troops. It has also been hypothesized that, because of the date of that particular road level and the details Harry described, the ghostly troopers may well have been part of the IXth Hispana Legion which had gone missing.

Who knows. If the shades of these legionaries experienced a traumatic slaughter in the highlands of Caledonia, then perhaps their ghosts eventually returned to Eburacum where they still march along the roads today?

Harry Martindale was not the only one to have seen the shades of these Roman soldiers over the years. Before him, the old caretaker had seen them, but said nothing for fear of being ridiculed. A later caretaker also saw them after Harry’s experience.

My guide in York claimed that other Roman legionary ghosts had been spotted marching down the streets of York at night too, and it’s not hard to imagine when you walk around that ancient city. It seems made for ghosts!

I don’t know if the latter is true, or if Martindale’s story is legitimate. It does seem odd though that a young working boy could have such a detailed knowledge of Roman legionary or auxiliary kit, doesn’t it?

Either way, it’s a fantastic Roman ghost story!

Earlier, I mentioned that there was a way in which you can be a part of the Roman Ghosts blog series…

If you know of any other Roman ghost stories in any country across what was the Roman Empire, then please do let us know about it and, if possible, send us a link to sources or articles that refer to that particular ghost story or sighting.

If you have any stories to share with us that you would like us to look at, just reply to this e-mail or go to the Contact Us page on the Eagles and Dragons Publishing website.

Anyone who makes us aware of a Roman ghost story that we write up will get a mention in the blog itself.

For now, we hope you’ve enjoyed this first post in the Roman Ghosts series.

Thank you for reading.

To watch an interview with Harry Martindale about his experience, check out the first half of the video below:

A Turn of the Thumb: Gladiators and the Thumbs Up

Greetings ancient history fans! We hope you enjoyed last week’s blog post on the origins of gladiatorial combat and the different types of gladiators. If you didn’t read it, you can check it out by CLICKING HERE.

This week we’re venturing farther into the world of gladiators with a special guest post by archaeologist Raven Todd Da Silva.

Everyone who is familiar with popular representations of gladiators and gladiatorial combat will be familiar with the ‘turn of the thumb’ gesture, but do you know how that expression came about? Is it historically correct? Why was the thumb so important to Romans?

Well, Raven is going to demystify that for us. Take it away, Raven!

A Turn of the Thumb: Gladiators and the Thumbs Up

By: Raven Todd Da Silva

The notion of signaling life or death for a defeated gladiator by a thumbs up or thumbs down has been made popular by famous pieces of artwork and the 2000 film Gladiator.

But what is the real importance of our thumbs (digitus pollex), and how did it really function in the gladiatorial games of Ancient Rome?

The Romans were unique in comparison to other civilizations in referring to the thumb as its own digit on the hand, and it’s suggested that they believed it to have power or hold sway (polleat) over the rest of the fingers. The Latin word for thumb, pollex, is also said to have derived from the word for power, pollet. So we can see here just how much influence a gesture with the thumb had.

In the days of the gladiatorial games, the audience could have their say in deciding the fate of the fallen combatants with a hand gesture – what we think of as thumbs up or thumbs down in today’s misconstrued pop culture-reliant society. The decision to kill the fallen gladiator was decided with what is know as the pollice verso – which translates only as “turned thumb”. If we look at Juvenal, he says:

to-day they hold shows of their own, and win applause by slaying whomsoever the mob with a turn of the thumb bids them slay. (Juvenal; Satire III 36)

The Christian poet Prudentius also backs this up when talking about a Vestal Virgin watching the games:

The modest virgin with a turn of her thumb bids him pierce the breast of his fallen foe (Prudentius; Against Symmachus II)

We aren’t sure what this exactly means though, and there are no other proper surviving texts to give us specific insight. Contrary to popular belief, the “thumbs up” we all know today as a sign of a good job or to show that everything is A-OK did not always have this meaning. A study by Desmod Morris shows that Italians did not consider this action as a positive one until American pilots, who used it to signal to the grounds crew that they were ready to take off, imported it in WWII.

So we don’t really know which way the audience’s thumbs were pointing to indicate if they wanted the gladiator to die.

But if an extended, turned thumb indicated the kill, what did the audience do if they wanted to spare the gladiator’s life? Martial stated that the crowd appealed for mercy by waving their handkerchiefs (XII) or by shouting (Spectacles, X).

It seems the gesture was possibly to hide your thumb inside of your fist known as the pollice compresso or “compressed thumb”. Anthony Corbeill, the leading expert on ancient Roman gestures has translated Pliny’s pollices premere to mean that a thumb pressed down on the index finger of a closed fist signified mercy.

There’s some speculation with the reasoning behind these two gestures. Firstly, it’s a lot easier to tell the difference from the crowd. Second, it could indicate the state of the gladiator’s sword. Extended thumb indicating that the audience wanted the gladiator to give the conquered one final stab or blow, and the compressed thumb telling the victor to sheath his weapon and grant mercy on the defeated.

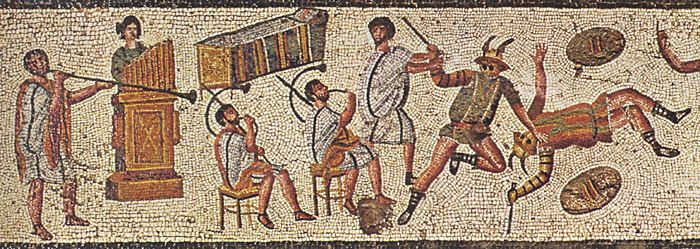

Archaeologically speaking, the The Médaillon de Cavillargues, located in the Nîmes Musée Archéologique supports Corbeill’s conclusions. Also interesting to note, the gladiator may have had to wait for a judgment call from the producer of the games to know the true outcome from the audience vote – waiting for an audible cue in the form of a horn or some music, which is suggested in the Zliten mosaic.

One of the most famous paintings depicting gladiatorial combat is called the Pollice Verso, painted in 1872 by famous historical painter Jean-Léon Jérôme. It displays a victorious gladiator standing over his vanquished opponent, showing off to a crowd enthusiastically thrusting their thumbs down. Jérôme was a highly respected historical painter, known for his extensive research and accuracy, which is why this misrepresentation lead to so many misunderstandings from the general public and fellow academics.

Raven Todd DaSilva is working on her Master’s in art conservation at the University of Amsterdam. Having studied archaeology and ancient history, she started Dig it With Raven to make archaeology, history and conservation exciting and freely accessible to everyone. You can follow all her adventures on Facebook and Instagram @digitwithraven

Resources

The Gladiator and the Thumb

“Thumbs in Ancient Rome: pollex as Index.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 42 (1997) 61-81 Anthony Corbeill

Juvenal Satire Book 3

Nature Embodied: Gesture in Ancient Rome (2004) by Anthony Corbeill

Zliten Mosaic

Pollice Verso

I’d like to thank Raven for taking the time to share this fascinating research with us. To be honest, I had no idea the Romans thought of the thumb as a digit that held sway over the other fingers!

You can read more by checking out the list of resources above.

If you have any questions for Raven about the ‘turn of the thumb’, you can ask them in the comments below.

Also, be sure to check out her website Dig It With Raven where she has a wealth of information on archaeology, history and art restoration.

Raven also posts regular VLOGS about archaeology and art restoration that are fascinating and highly informative. She’s also really funny! For anyone wanting to get their feet wet in these subject areas, I can’t recommend the videos enough. Make sure you subscribe to her YouTube channel so you don’t miss any of her awesome and educational videos.

We’ll definitely have Raven back on the blog!

Thanks for stopping by, and thank you for reading!

Gladiators: The Implements of Death

Few things about the ancient Roman world fascinate the modern masses more than gladiators. The subject of slaves dueling to the death for the entertainment of the mob is horrible, but at the same time darkly entertaining.

In the popular mind, most of what we imagine gladiators and gladiatorial combat to have been comes from popular movies and television. I still remember the first time I watched Spartacus as a kid, and the horror of the scene when Kirk Douglas fights his fellow gladiator, Draba (played by Woody Strode) and how the latter is cut down when he refuses to kill Spartacus. It made my heart race and guts tighten. A lasting impression to be sure!

And who can forget the more recent film, Gladiator, by Ridley Scott, with its epic fight scenes and recreation of the Flavian Amphitheatre, or rather, the Colosseum? Classics enrollment shot through the roof after that movie! What about the television series, Spartacus: Blood and Sand?

Bloody, brutal, entertaining and mesmerizing.

Apart from Spartacus: Blood and Sand, however, few attempts have been made to properly portray gladiators and their equipment, their styles. The focus in the media has been on death and the panem et circenses, or ‘bread and circuses’, aspect of it all.

In this post, we’re going to look at the various styles of gladiators, along with some of their weapons. The reality of gladiatorial combat in the major arenas of the Roman Empire was not of two half-naked men slashing away at each other, but rather of a highly organized blood sport with its own set of rules.

But before we delve into that, let’s take a brief look at the origins of gladiatorial combat.

Funeral Games were an ancient tradition. The Games in honour of the death of Patroclus beneath the walls of Troy are depicted here.

Originally, it’s thought that gladiatorial contests were not for entertainment, but rather for funeral games.

Possibly the oldest depiction of a gladiatorial contest comes from a tomb painting at Paestum, in Campania, around 370-340 B.C. The murals of this tomb portray various activities such as chariot races, fist fights, and a dual between armed men bearing, helmets, shields, and spears. A referee and three pairs of fighting men are also depicted.

Because of this find, and the presence of the oldest stone amphitheatres in the region, it has been argued that Campania is where gladiatorial fights originated. The region was also home to some of the most important gladiatorial schools, or ludi.

The idea of shedding blood by a dead person’s grave, was an ancient tradition, and the Roman world was no stranger to blood sacrifice. You can read more about sacrifices in the Roman world HERE.

However, later Roman writers, such as the Christian writer, Tertullian (c. A.D. 200), frowned upon this particular rite of sacrifice:

For of old, in the belief that the souls of the dead are propitiated with human blood, they used at funerals to sacrifice captives or slaves of poor value whom they bought. Afterwards, it seemed good to obscure their impiety by making it a pleasure. So they found comfort for death in murder. (Tertullian, De Spectaculis 12)

Tertullian, in a way, displayed a mindset more in tune with our own, perhaps, in which most of us feel horror at the thought of public execution and torture. This is a modern mindset, however. When it came to early gladiatorial combat, it does indeed appear that life was cheap when it came to the first gladiators who were most likely prisoners of war and slaves.

Over time, gladiatorial combat moved from being a rite for funeral games, to an entertainment for the masses. ‘Bread and circuses’ as Juvenal put it in the second century A.D.

With the growing popularity of gladiatorial combat, the aristocratic families who wanted to maintain their political power in Rome began to use the games as a means of securing their power. They did this by putting on public games for the masses, the mob. It became an expensive entertainment to put on, and also a part of everyday life in the Roman world.

The first public gladiator fight was apparently in the Forum Boarium, but later they occurred in the Forum Romanum, and then, once it was built, found a permanent home in the Colosseum.

Gladiatorial contests grew in popularity, and these slaves, for that is what they were, came to be superstars, second only, you might say, to charioteers.

Though the Romans may not have invented gladiatorial combat, they do appear to have ‘perfected’ it. They developed ludi, gladiatorial schools run by a lanista. In the Roman Empire, the state came to exert a level of control – there were four imperial ludi in Rome itself! There were styles of gladiator with specialized weapons and training, diet and the best medical care. And gladiators were no longer just prisoners of war or slaves, but also criminals and even volunteers!

Gladiators were also an investment. They developed a market value depending on their successes. Gladiators were to ancient Rome, what our modern-day sports superstars are now. They were part of a great show, complete with stage sets and storylines. They even had stage names, their images popping up in scrawled graffiti all over Rome, etched by their adoring fans.

Mosaic depicting gladiators with their stage names. Note the theta symbol (a circle with a line) beside some which stands for ‘Thanatos’, indicating that they are dead.

At this point, you get the picture. Gladiators evolved from being a sacrifice, to superstars in the world of Roman blood sport.

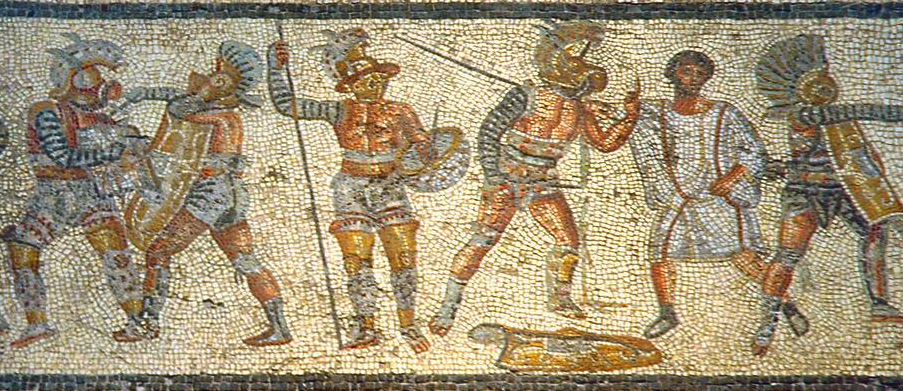

However, it wasn’t just a matter of matching any type of gladiator against another. There were specific styles that developed over time, and they stemmed from mythological beasts to shadows of Rome’s former enemies.

Pairings of the different types of gladiators were not random. You might be surprised to know that the rules called for very specific types of gladiators to be pitted against each other, especially in the great amphitheatres of the Empire.

Much of what we know of the equipment of the different types of fighters comes from pictorial depictions on anything from elaborate mosaics, to frescos, oil lamps and even street graffiti.

An ancient oil lamp decorated with a gladiatorial combat scene. The perfect addition to any young man’s cubiculum!

The different classes of gladiators had distinctive equipment, and protection was worn on different parts of the body, depending on the style. Usually, the head, face and throat were protected by a helmet, and some of these are the most impressive remains of gladiatorial equipment. Different limbs were also protected by organic materials like leather and linen, but there were also metal guards such as greaves.

In almost all cases, the gladiator’s chest, no matter the style, was unprotected, but for the provocator which we will look at shortly. The only piece of clothing worn was a loin cloth, or subligaculum, which was belted with a cingulum or later, a wide sash.

There were variations on some of the protective equipment such as manicae, which were arm guards worn regularly in late antiquity, and fasciae, padded tubes for the legs which could be worn beneath greaves.

The first type of gladiator we are going to look at is the eques, or horseman.

Equites fought only against other equites, and were considered lightly-armed gladiators. They were the only gladiators to wear clothing, in the form of a tunica, and they wore gaiters on their legs, but no greaves. They had a manica on their right arm, wore a visored helmet, and carried a parma equestris, a round cavalry shield.

As far as weapons, the eques carried a hasta, which was a lance of about 2.5 meters in length, and a gladius.

More often than not, the equites bouts would take place at the beginning of the gladiatorial combat schedule during the games.

Probably the most famous or recognizable gladiator style was the heavy-armed murmillo.

Murmillo is actually a term for fish, and the style of his helmet resembled something of a sea creature or monster in a way. He was usually set against a thraex (Thracian) fighter, or a hoplomachus (a Greek style fighter).

When you look at this fighter, you can tell that it was a formidable opponent, and from the weapons, one could say that in the combat against others, he represented Rome and Rome’s army.

The murmillo’s torso was bare and he was protected by a manica on his right arm, and a gaiter and short greave on his right leg. The head was protected by a wide-brimmed helmet with a crest and feathers, and he bore a heavy scutum in his left hand, the large rectangular shield of Rome’s legions. Because of this protection, the murmillo fought with his left foot and shoulder forward, striking with the only weapon he carried, a gladius, in his right hand.

The murmillo never fought against his own kind, and it seems likely that the pairing of a murmillo against a thraex was the most common pairing in Roman amphitheatres.

As mentioned, the thraex fighter, named after Rome’s Thracian enemies, was the main opponent of the murmillo, and was also a heavy class fighter.

The equipment of the thraex is often confused with the hoplomachus because of certain similarities such as quilted leg protection, two high greaves that reached above the knee, and a brimmed helmet with a tall crest.

The thraex carried a smaller, almost square shield known as a parmula, and his helmet was often decorated with a griffin. He had a manica on his right arm as well. Unique to the thraex was the distinctive curved short sword or sica.

In addition to being the main opponent of the murmillo, the thraex was also pitted against the hoplomachus.

Hoplomachus literally means ‘fights with a weapon’, which is rather obvious for a gladiator, but this heavy class fighter was representative of the ancient Greek hoplite warrior who was named after the round hoplon shield.

However, the circular shield carried by this gladiator was a smaller bronze version of the Greek shield. In addition to the body protection in common with the thraex mentioned above, the hoplomachus carried two weapons: a long dagger in his left hand, to which the shield was strapped, and a lance or spear in his right hand.

The hoplomachus usually fought a murmillo, although he could be matched against the thraex. The pairings were part of the show, an imitation of Roman soldiers (murmillo) against the foreign enemies of the past.

The only middle weight gladiatorial class appears to have been the provocator.

This style of gladiator usually fought his own type, and was the only one with a protected chest in the form of a square or rectangular breastplate. He also had a half-length greave.

The provocator carried a rectangular shield, similar to a scutum and carried a gladius as his weapon. His helmet had a visor but no crest.

These fighters may not have been the headliners of the show, but their lighter weight must have made for a quick, equally-matched and impressive fight.

Apart from the murmillo, the retiarius is probably the most iconic symbol of the gladiatorial family.

The name retiarius, means ‘fights with a net’.

This fighter was one of the few who had no helmet. Nor did he have a greave or shield. However, the retirarius did have a manica protecting his left arm, as well as a galerus, a tall metal shoulder guard. His weapons consisted of a net, a trident, and a pugio, or dagger.

Surprisingly, this fighter was a new category that was introduced during the imperial period. He was a light fighter, and though he did not pit well against the heavy, military-themed fighters, he was sometimes pitted against them during the Empire. Most often, however, the retiarius met the secutor on the sands of the arena. Sometimes, he even fought against two secutores!

The pairing of a retiarius and secutor was a storyline, a tale of the fisherman against a sea creature(s). Sometimes a set or stage was erected on the arena floor for this performance, with a bridge, or pons, from which the retiarius could fight against his one or two foes. At times, they even fought over real water!

The secutor, the opponent of the retiarius, was also sometimes called a contraretiarius.

This gladiator was similar to the murmillo, but was designed specifically to fight the retiarius. He differed from the murmillo in the type and shape of helmet that he wore. Not only did the helmet look like a fish or sea creature, but it also had small eye holes that were deliberately intended to protect the fighter against the points of the retiarius’ trident. His hearing and vision were severely hampered by the helmet, but his heavy protection evened the odds against his more agile opponent. The secutor was not a fighter to mess with!

Those were the main types or classes of gladiators that appeared across the Roman Empire and in the amphitheatres of Rome.

However, there were other types of gladiators such female gladiators who depicted Amazon warriors, as well as gladiators with regional variations in the provinces.

Some other types included the essedarius, or war-chariot fighter who represented Rome’s Celtic enemies, the dimachaerus who was a fighter with two swords or daggers, and the crupellarius who was a sort of super heavy-armed gladiator.

There was also the aquerarius, a sort of retiarius with a lasso or noose, and the saggitarius who, you guessed it, was an archer gladiator. Between bouts, or at the half-time intermission of the games, you might also catch a glimpse of the paegniarius who was not for fighting, but more for comic relief like the clowns during a half-time show or intermission.

The world of gladiatorial combat was vast and better regulated than we are led to believe in movies. We’ve but scratched the surface here. The combats were not only on sand between men, but there were also venatio (wild animal hunts), and naumachiae (mock naval battles) to entertain the masses of Rome and the Empire.

There is much more to learn about this bloody aspect of Roman society and sport. If you want to read more, two very accessible books are Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome edited by Eckart Kohne and Cornelia Ewigleben, and the Osprey Publishing ‘Warrior’ series book Gladiators: 100 B.C. – A.D. 200 by Stephen Wisdom and Angus McBride.

But we aren’t done with gladiators!

Very soon on the Writing the Past blog, we’ll have a special guest post from archaeologist Raven Todd Da Silva about the infamous ‘turn of the thumb’ in gladiatorial games. Make sure that you are signed-up to the Eagles and Dragons Mailing List so that you don’t miss Raven’s post or any others that are coming up!

For now, I hope you’ve enjoyed this peek into the world of gladiators.

Thank you for reading.

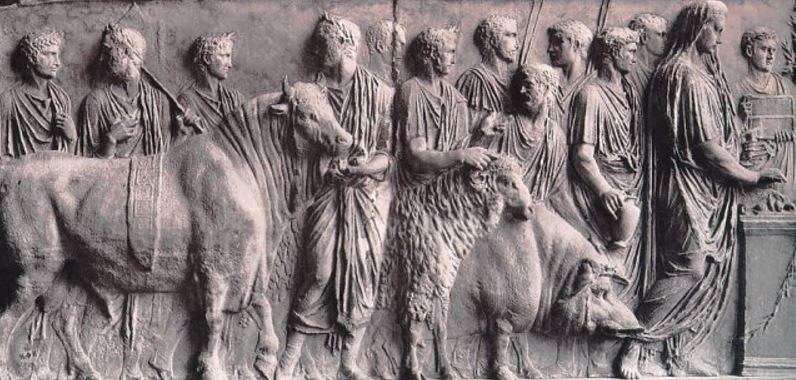

Sacrifice in the Roman World

Oftentimes, when we think of the world of ancient Rome, one of the images that springs to mind is that of the sacrifice, the image of a priest before an altar slashing the throat of some sort of animal, the blood of which oozes in grisly flow down the sides of a white marble altar.

It’s a dramatic image to be sure, but it does not provide us with the complete facts of sacrifice in Roman society.

Today, we are going to take a brief look at sacrifice in Roman religion, what it meant and what it could entail.

Basically, a sacrifice, or sacrificium, was a gift to the gods, heroes, emperors, or the dead. It was not simply a matter of the ritualistic killing of animals as is our modern perception of ancient sacrifice.

Not all sacrifices were blood sacrifices, and not all sacrifices were public displays either. There were also private sacrifices.

Whether public or private, the goal was to maintain one’s relationship with the gods, the dead, etc. and this was done in different ways.

Food offerings were not only of flesh, but could also be of fruit or grain, milk, honey or something similar.

Depending upon the nature of the offering and its intent, a food offering might be part of a sacrificial feast in which people shared with the gods, both receiving their portion to consume. Alternatively, the entirety of the sacrifice might be offered to the gods to be consumed in the flames.

Most of the evidence for sacrifices in the Roman world come to us from inscriptions on altars which were themselves considered sacrifices.

There could be various reasons for a sacrifice such as one made in expectation of a favour, or a sacrifice that was demanded by the gods through an oracle, omen, dream or some other such occurrence. Sacrifices were also made on anniversaries, such as the anniversary of a family member’s death or an historic event, or they could be made as part of a religious festival.

Roman religion was customizable in a sense, and so the types of gifts of sacrifices could vary. They might include cakes, incense, oils, wine, honey, milk, and perhaps sacred herbs or flowers. And yes, they could also include various blood sacrifices with certain types and colour of animals being more fitting for certain gods.

One of the most common forms of sacrifices were those made in fulfillment of a vow, meaning that if a particular god undertook a specific action on behalf of the mortal making the request, then that mortal would carry out the promised sacrifice. Perhaps that mortal would build an altar to that god if his political campaign was successful, or perhaps a general would sacrifice fifty bulls if he was victorious on the battlefield?

When it came to the slaughter of animals as part of a sacrifice, it seems that male animals were offered to male gods, and female animals to goddesses. They had to be free of blemishes and a suitable colour as well, for example, black for underworld gods. There were also times when the animal sacrificed was one that was considered unfit for human consumption, such as the sacrifice of dogs to Hecate.

It does not appear to have been usual for a regular citizen to perform an animal sacrifice. It was more the case that the person who wanted to make the sacrifice made arrangements for the ceremony with the aedituus of a particular temple who hired a victimarius to perform the actual slaughter. There might also have been music provided by a flute player, or tibicen, in order to please the god but also to cover up any sounds of ill-omen from the victim.

For most sacrifices, a priest would have his head covered by the folds of a toga to guard against ill-omened sights and sounds, except at Saturnalia when things were the reverse of the usual and priests performed sacrifices with their heads uncovered.

Notice the covered head of the person performing the sacrifice, and the poleaxe carried by the victimarius leading the bull to slaughter.

One might think that it was an easy thing to slaughter an animal, but it seems that the opposite is the case. Aside from trying to avoid any ill-omened sights or sounds, the way in which an animal was slaughtered was very important to Romans.

The head of the animal was usually sprinkled with grains, wine, or sacred cake known as mola salsa before it was killed. It was then stunned with a blow to the head, perhaps with a ceremonial axe or cudgel, and then stabbed or its throat slit with a sacrificial knife. The blood was then caught in a special bowl and poured over the altar.

Once the sacred deed was done, the animal was skinned and cut up. It is at this point that a haruspex might examine the entrails for messages or omens from the gods.

The remains were roasted over the fire with the entrails consumed first. Bones wrapped in fat, the preferred portion of the gods, were then burned upon the sacred fire along with other offerings such as wine or oil. If it was part of a sacrificial feast, the remaining portions were then roasted for the mortal participants.

Blood sacrifices could be performed for different occasions that also included times of crisis, such as if Hannibal was at the gates of Rome, for the purposes of purification, or for the rites of the dead.

Chillingly, I only recently discovered that a holocaust was a sacrifice in which the victims were completely burned.

Another type of sacrifice that was well-known in ancient Rome was the suovetaurilia which involved the sacrifice of a pig, a sheep, and an ox. No doubt this particular sacrifice made for a good meal afterward for the participants.

But what about human sacrifice in the Roman world?

It is thought that early gladiatorial combat was a form of sacrifice, but there is little evidence for regular human sacrifice over time.

It was practiced only in exceptional circumstances such as after disasters in battle. One example is in 216. B.C., after the battle of Cannae when the Sibylline Books were consulted, a pair of Greeks and a pair of Gauls were sacrificed by being buried alive in the Forum Boarium of Rome. Titus Livius (Livy) recounts the latter here:

Since in the midst of so many misfortunes this pollution was, as happens at such times, converted into a portent, the decemvirs were commanded to consult the Books, and Quintus Fabius Pictor was dispatched to Delphi, to enquire of the oracle with what prayers and supplications they might propitiate the gods, and what would be the end of all their calamities. In the meantime, by the direction of the Books of Fate, some unusual sacrifices were offered; amongst others a Gaulish man and woman and a Greek man and woman were buried alive in the Cattle Market, in a place walled in with stone, which even before this time had been defiled with human victims, a sacrifice wholly alien to the Roman spirit.

(Livy; The History of Rome 22.57.6)

Human sacrifice was eventually outlawed by senatorial decree in 97 B.C., though the practice might have continued in some non-Roman cults for a time. It does seem that effigies or masks could have replaced actual human victims in some rites.

Whether they took place in a public forum, in one of the main temples of Rome, or in the lararium of a private domus, it seems evident that sacrifice was central to Roman religious practices.

The sacrificial offerings varied greatly from animal and human flesh, to wine, oil and incense, to other foods such as cakes, grains, flowers and more. Sacrifices could also include altars and the building of monuments.

What mattered was that the gods were propitiated and the dialogue between the earthly and divine realms was maintained and respected.

To me, Roman religion and sacrifice are crucial to our understanding of the ancient Roman world. It’s a fascinating subject that still holds many mysteries, and I hope that you have found this brief look interesting.

Thank you for reading.

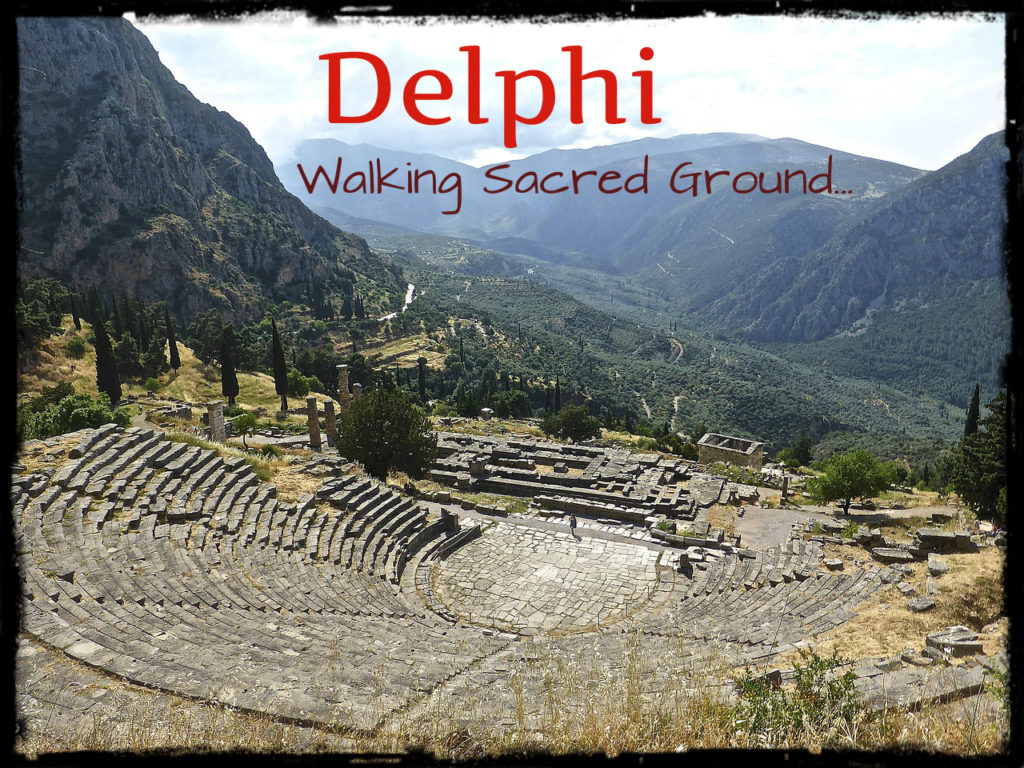

Delphi – Walking Sacred Ground

Happy New Year everyone!

Welcome to a new year for Writing the Past and Eagles and Dragons Publishing. We’re so glad you’re here to share in our love of history, archaeology, myth and legend.

In many posts on this blog I have mentioned some of the great sanctuaries of antiquity such as Delos, Olympia and Nemea. I have touched on the special feeling one gets when walking around these places, the sense of peace that washes over you.

Today, we’ll be taking a short tour of one of the most important sanctuaries of the ancient world: Delphi.

Delphi was of course the location of the great sanctuary of Apollo whose priestess, the Pythia, was visited by people from all over the world who came to seek the god’s advice and wisdom.

I have been fortunate enough to visit Delphi a couple of times, and I do hope to return there someday soon. The first time I was there, the mountain rumbled throughout the night. Unused to earthquakes, my brother woke me to say that he thought there was a ghost in the room because his bed (he had the smaller one) was jumping up and down. Looking back, it’s funny that ghosts were a more logical explanation for us. Too many movies, I suppose.

But, despite frequent earthquakes, Delphi is indeed a place of ghosts. They are everywhere, the voices of the past, of the devoted, great and small.

There is something about Delphi that draws you in, that makes you want to go back again and again. Despite the throngs of picture-snapping tourists along the Sacred Way, or the hum of multi-lingual tour guides wherever you step, the sense of peace at Delphi is unmistakable.

For those with the ability to see and hear beyond the bustle, it is as though a smoky veil rises from the ground to block out the noise, leaving you with the mountain, the ruins, the voices of history.

Delphi is located in central Greece in the ancient region of Phokis. Perched on the slopes of Mount Parnassos in a spot one can well imagine gods roaming, it possesses a view of a valley covered in ancient, gnarled olive groves spilling toward the blueness of the Gulf of Corinth.

Though the site is always associated with him, Apollo did not always rule here.

Long before the Olympian god arrived, Delphi was the site of a prehistoric sanctuary of Gaia, the Mother Goddess and consort of Uranus.

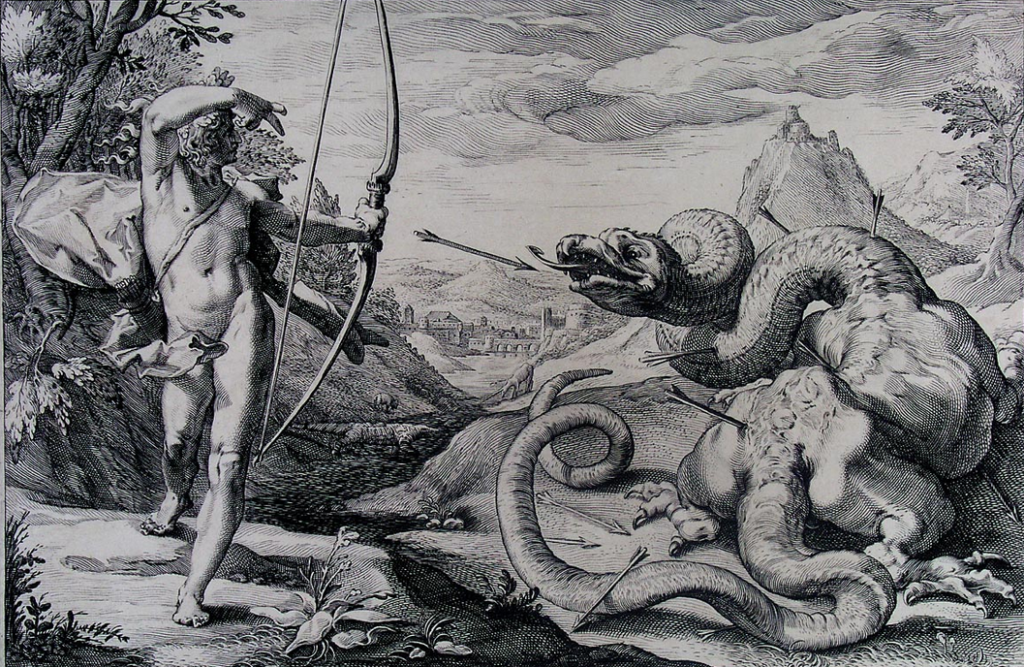

It was after Apollo, urged on by his mother Leto, defeated the great python in the sanctuary of Gaia that Delphi came under his protection.

A new era had dawned and after Apollo’s slaying of the Python, barbarism and savage custom were discarded. In place of the old religion came a quest for harmony, a balancing of opposites. Apollo was worshiped as a god of light, harmony, order and of prophecy. His oracles communicated his will and words.

If one approaches Delphi from the East and the town of Arachova, the first thing you pass is another important sanctuary, that of Athena Pronaia. ‘Pronaia’ means ‘before the temple’. This sanctuary would likely have been visited by pilgrims first.

The sanctuary of Athena is farther down the mountainside from that of Apollo and located in a quiet olive grove. In its time, it contained two temples dedicated to Athena, the earliest dating to 500 B.C. There were also two treasuries, altars, and of course, one of the most picturesque ruins of ancient Greece, the round tholos temple. The latter is 13.5 meters wide and had twenty Doric columns with metopes portraying the Battle of the Amazons and the Battle of the Centaurs, the remains of which can be seen in the Delphi museum. The exact use of the tholos is uncertain though many believe it was consecrated to the cult of deities other than Apollo or Athena.

Between the two sanctuaries is the sacred spring of Kastalia, the water of which was intimately associated with the oracle. Water from here was carried to the sanctuary of Apollo and it was also here that priests and pilgrims cleansed themselves before entering god’s domain.

As part of her ritual too, the Pythia bathed in the Kastalian spring before entering the Temple of Apollo.

When the Pythia was prophesying, Delphi must have been bustling, for she was not always there. In fact, in its early days, the oracle performed her function once a year on the 7th day of the ancient month of Bysios (February-March) which was considered Apollo’s birthday. Later, the Pythia prophesied once a month, apart from the three winter months when Apollo was said to spend time in the land of Hyperborea far to the north.

I won’t describe all the remains of the sanctuary of Apollo in detail here. There is far too much to cover and it is all fascinating. I will say that it is one of those places that every lover of history must visit.

When I think of history, the study of it, this place is what it’s all about.

On your way through the sanctuary you pass many remains, one of the most interesting being the Athenian treasury which held many rich votive offerings from the ancient polis. It is well preserved and some of the most interesting things are the inscriptions of the Hymns to Apollo and carvings of laurel leaves upon its walls.

On the left, once you leave the Athenian treasury, there are two large boulders. They look to be nothing more than rocks but these were of utmost sanctity thousands of years ago. The smaller of the two is called Leto’s Rock because it is believed that that is where Apollo’s mother stood when she urged him to slay the python. The larger rock is called the Sibyl’s Rock as that is where the first oracle (‘Sibyl’ is another name for Apollo’s oracles) stood when she came to Delphi and gave her first prophecy.

Each time I walk the marble of the Sacred Way up to the Temple of Apollo, the theatre and the stadium beyond, I am in awe. The sun seems more brilliant here, the colours richer. The buzzing of cicadas in the pine and olive trees are sounds ancient pilgrims would have been familiar with. It would have been crowded during the time of prophecy, and the line must have wended its way down the mountain to Kastalia and the sanctuary of Athena.

Every part of the sanctuary would have been adorned with bronze and marble statues, tripods, altars and other offerings from around the world. The smoke of incense and sacrifice would have weaved among it all to please Apollo and other deities who also had altars about the temple, such as Zeus, Poseidon, and Hestia, whose immortal flame was never extinguished.

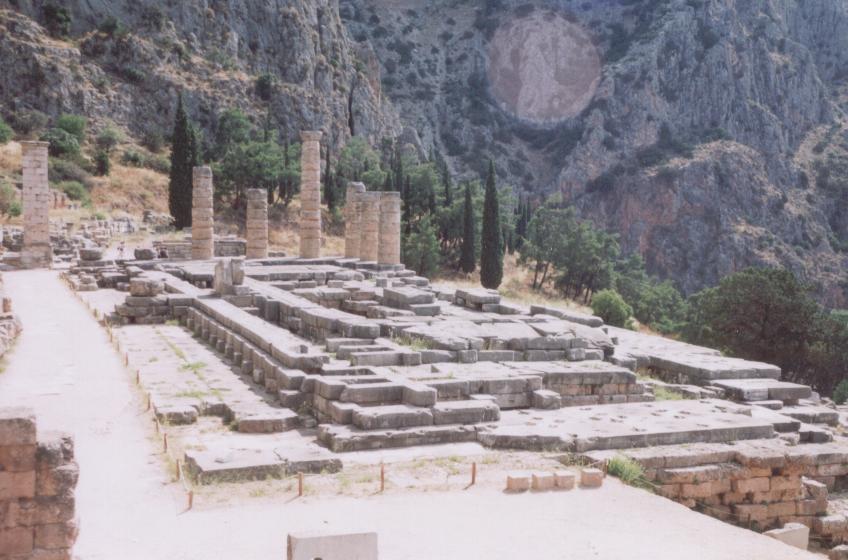

The Temple of Apollo itself occupies a magnificent position and though not much remains, it is still a place of awe due in large part to the surroundings. The layout is not known exactly due to damage over time, but archaeologists have discovered that there were two cellae (temple chambers), an outer one where priests and pilgrims remained, and an inner one.

The inner cella is believed to have been the subterranean chamber where only the Pythia herself was permitted. This chamber was where she prophesied. It contained another sacred spring, the Kassiotis spring, from which she drank, a crack in the earth from which fumes emanated, the oracular tripod in which she sat, and the sacred omphalos, or, ‘navel of the earth’.

The Pythia would chew laurel leaves, inhale the fumes from the earth, and go into her trance. She would deliver her prophecy in riddles which were delivered to pilgrims.

To a modern mind, the ancients might seem absurdly superstitious, naïve even. But, in the ancient world the respect and awe with which the oracle of Delphi was viewed cannot be overestimated.

The truth of the oracle was never doubted for matters great or small. Cities, peoples, peasants and kings all sought the wisdom and guidance of Apollo through the oracle.

When I reach the top of the site and look out over the sanctuary to the valley and sea beyond, I feel that I do not want to leave. From the top of the third century B.C. theatre, or in the quiet of the stadium that once held 7000 spectators for the Pythian games, I reflect on my own journey, and on the myriad journeys of those who have come here before over the millennia.

The Stadium farther up the mountain from the sanctuary was the site of the Pythian Games and seated up to 7000 spectators

As a writer, I find people fascinating. What brought each of them to this place? What questions might they have asked? How did they receive the answers given by the oracle? I touch on this through my characters in Killing the Hydra.

Delphi was not just the site of some quaint, ancient, superstitious practices as some might see them today. This was a place of power, of beauty, refinement and of hope. In some ways, it still is.

The Pythia is gone, the sacred games long-since banished by the Christian Emperor Theodosius I. The temple and the treasures of the sanctuary have been looted, and what is left lies in romantic ruin, or on display in the museum.

However, if your path ever leads you to this ancient place on the slopes of Mount Parnassos, you may just hear the pilgrims’ prayers to the gods, the melodic utterings of the ancient hymns, and the hushed voice of the Pythia, beyond the veil of this world, as she passes Apollo’s words on to generations of mortals seeking his wisdom.

Thank you for reading…

Have you ever visited Delphi? If so, tell us what your impressions were in the comments section below.

Happy Holidays from Eagles and Dragons Publishing!

Thank you to all of our followers and supporters for making 2017 an amazing year!

We have the best fans, and we really appreciate the time you spend reading our books, blogs, and interacting on social media.

Here’s to a happy and safe holiday season, and may 2018 be a fortunate year for all.

Cheers and enjoy!

Sincerely,

Adam and the Eagles and Dragons Publishing Team

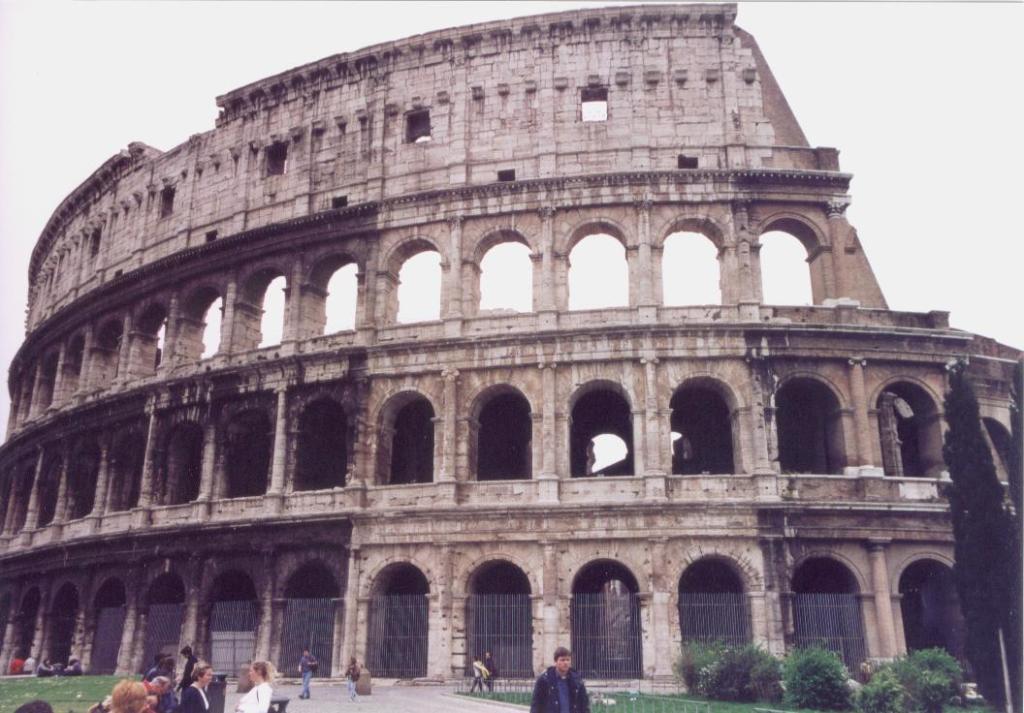

The Colosseum: First Impressions and Edgar Allan Poe

We all have our memories of first impressions – of people, of feelings, of almost every activity we undertake or situation we encounter.

For me, the first impression of an historical site is always something that is seared onto the memory of my heart and mind. Some sites leave more of an impression while the memories of others linger for a short time before melting away to form part of my broader perception of a period or place.

Back in 2000, one such site that left a titanic, long-lasting impression upon me was the Colosseum in Rome.

I remember it vividly, walking along the thick paving stones of the via Sacra from the Forum Romanum, past the arch of Titus. I was busy talking with my wife when I looked up to find that most famous of Rome’s monuments staring down at me.

It literally stopped me in my tracks.

Prior to that, I had read much about Rome and the Colosseum, but nothing can really prepare you for the moment you come face-to-face with such a creation.

It reached to the sky, arch upon arch, dominating the entire area. The moment I looked upon it, I could hear the cheering and jeering of the crowds, the clang of gladii, and the roar of wild beasts.

This monument of stone and bloody memory came to life, no…exploded into life!…before my very eyes.

It was at that moment that many parts in my books Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra began to take shape. In fact, my first visit to Rome to see the Colosseum, and indeed the vast ruins of the Forum Romanum and the Palatine Hill, helped me to truly understand the might and majesty of the Roman Empire.

I explored that ruin as much as I could from the outside to the interior corridors and sloping walls of the inside where upwards of 50,000 ancients once sat. I was ignorant of the masses of tourists, the myriad foreign languages being spoken, or the hucksters in cheap ‘Roman’ armour who charged unsuspecting tourists for a photo op while groping them.

It was the Colosseum that had us spell-bound.

It was a true wonder to me, and that first impression set me off on a journey into the past that has led me on many an adventure, both creative, cerebral and physical.

In a way, that first meeting made the world of ancient Rome my home.

A couple of months ago, I was reminded of my first impression of the Colosseum when reading another work inspired by this magnificent relic of history.

I was reading from the works of that father of American Gothic poetry and literature, Edgar Allan Poe, and came across his poem The Coliseum published on October 26, 1833, in the Baltimore Saturday Visiter.

I hadn’t read the poem before. In truth, I didn’t even know about it.

Of course, I read it and, well, it made me realize that the Colosseum has likely left an impression on everyone across time who has come across it since the inaugural games of A.D. 80.

I’m not going to analyze the poem here, but rather leave you to read it for yourself and experience a first impression through the eyes of Edgar Allan Poe.

I hope you enjoy…

The Coliseum

By Edgar Allan Poe

Type of the antique Rome! Rich reliquary

Of lofty contemplation left to Time

By buried centuries of pomp and power!

At length- at length- after so many days

Of weary pilgrimage and burning thirst,

(Thirst for the springs of lore that in thee lie,)

I kneel, an altered and an humble man,

Amid thy shadows, and so drink within

My very soul thy grandeur, gloom, and glory!

Vastness! and Age! and Memories of Eld!

Silence! and Desolation! and dim Night!

I feel ye now- I feel ye in your strength-

O spells more sure than e’er Judaean king

Taught in the gardens of Gethsemane!

O charms more potent than the rapt Chaldee

Ever drew down from out the quiet stars!

Here, where a hero fell, a column falls!

Here, where the mimic eagle glared in gold,

A midnight vigil holds the swarthy bat!

Here, where the dames of Rome their gilded hair

Waved to the wind, now wave the reed and thistle!

Here, where on golden throne the monarch lolled,

Glides, spectre-like, unto his marble home,

Lit by the wan light of the horned moon,

The swift and silent lizard of the stones!

But stay! these walls- these ivy-clad arcades-

These moldering plinths- these sad and blackened shafts-

These vague entablatures- this crumbling frieze-

These shattered cornices- this wreck- this ruin-

These stones- alas! these grey stones- are they all-

All of the famed, and the colossal left

By the corrosive Hours to Fate and me?

“Not all”- the Echoes answer me- “not all!

Prophetic sounds and loud, arise forever

From us, and from all Ruin, unto the wise,

As melody from Memnon to the Sun.

We rule the hearts of mightiest men- we rule

With a despotic sway all giant minds.

We are not impotent- we pallid stones.

Not all our power is gone- not all our fame-

Not all the magic of our high renown-

Not all the wonder that encircles us-

Not all the mysteries that in us lie-

Not all the memories that hang upon

And cling around about us as a garment,

Clothing us in a robe of more than glory.”

Isn’t that wonderful?

If you have had the chance to visit the Colosseum yourself, please do tell us what your own first impressions of it were in the comments below.

Thank you for reading.

Ancient Everyday – Oil Lamps in Ancient Rome

Salvete, dear readers!

My power went out the other night, and I found myself in darkness for a time but for the cold blue light of my phone.

Oddly enough, this made me think of another Ancient Everyday to share with you!

Lighting is something that we certainly take for granted today. We flick a switch and voila, we have light! If we want add to the atmosphere of a dinner party, we light candles for ambiance.

But in the ancient world, it was quite different. No switches, no electricity running through the walls of every domus.

The Romans, and the Greeks before them, used oil lamps.

Today, when we shop for lighting, there are myriad choices for size, quality and the amount of ornamentation upon a lamp.

The same can be said of oil lamps in the ancient world!

Oil lamps made out of bronze or pottery were in use in the Mediterranean world from about the seventh century B.C., and continued as such for centuries. Most consisted of a chamber for the oil, a filling hole in the middle, and another hole in the nozzle for a linen wick. Some lamps even had a handle for ease of carrying.

Most oil lamps were made in two-piece molds that were made of gypsum (calcium sulphate) and plaster. When the lamp was removed from the mold, it was dipped in a slip of clay (kind of a thick liquid clay mixture) to further coat the lamp and make it more impermeable to oil.

You can see how the molding process works HERE.

A Roman volute lamp with a gladiator or warrior depicted on the body and the producer’s name on the bottom

The oil that was usually used in oil lamps was, of course, olive oil. After all, it was widely available in the Mediterranean world.

Lamps of the second and third centuries B.C. that were used by Romans in Italy were more often than not imported from Athens where there was a significant ceramic industry. However, from the first century B.C. oil lamps used by Romans were mostly produced in Italy itself, and then exported around the Empire. Later on, these were then often copied by local producers in places such as Britannia.

From the Augustan period onward in Italy, high-quality volute oil lamps were produced. These were wide and flat with room for more ornamentation or scenery depicted in the middle, and curved ornaments to either side of the nozzle(s).

In the northern provinces especially, the Roman firmalampe became quite common. It was more plain than the decorative volute lamps, and purely functional. The firmalampe was made across the Empire.

At one point in time in the northern part of the Empire, it’s believed that there was a disruption to the oil supply from the Mediterranean, and so oil lamp production in the northern provinces slowed to a standstill. Instead, candles made of tallow (beef and sheep fat), which the Romans had used to an extent since around 500 B.C., may have begun to replace oil lamps.

However, in the olive oil-producing regions of the Empire, oil lamps in countless different styles were still widely used to light the domus of many a Roman.

Thank you for reading.

A more ornate, double-nozzle, bronze oil lamp with stand and acanthus handle. Only the very best for these owners!