Facing Fear with the 300 Spartans

Hear your fate, O dwellers in Sparta of the wide spaces;

Either your famed, great town must be sacked by Perseus’ sons,

Or, if that be not, the whole land of Lacedaemon

Shall mourn the death of a king of the house of Heracles,

For not the strength of lions or of bulls shall hold him,

Strength against strength; for he has the power of Zeus,

And will not be checked till one of these two he has consumed.

Thus spake the the Oracle at Delphi, long ago, as recorded by Herodotus, the ‘father of history’, in Book 7 of The Histories. This was the prophecy that was given prior to the Greek stand at Thermopylae in which 300 Spartans and 700 men of Thespiae made one of the most heroic stands in the history of the world. Roughly one thousand Greek hoplites defended the pass known as the ‘hot gates’ (photo above) for three days against an army of about 1 million under Xerxes of Persia. This is a deed of heroism by which all others have been measured in western history ever since, and it echoes across the ages, unspoilt, radiant, despite politics and the greed of much lesser men.

Why is it that this single event in western history is revisited again and again? What do we get out of it today when our lives are so very different from those of 480 B.C.? There are probably several answers to that question, but for myself, it’s summed up in one word: Inspiration.

I know, “there he goes again, on about inspiration. Totally corny.”

Not to me. Inspiration, whether conscious or unconscious, is highly individualistic. I’ve stood on the battlefield of Thermopylae, and though there is a motorway running through it, and the sea has silted up for kilometers, the place casts a spell. It’s not the impressive modern monument to Leonidas of Sparta and his men that I find moving, but rather the little hillock on the other side of the road where the Spartans made their last stand, where they died for what they believed in, for their way of life.

It’s difficult for the modern mind to grasp this concept, no doubt, and out of misunderstanding, or perhaps fear, many might dismiss this as something that happened long ago. These men and their king volunteered for death, and they shall never be forgotten. They lived strongly, true to themselves. They’ve been celebrated through history to the modern age. Artists, filmmakers and yes, writers, have paid their tributes.

I remember seeing a picture of American troops in Afghanistan, sitting in the sand reading copies of Gates of Fire by Steven Pressfield (sadly, I couldn’t find the picture again to share with you). I think of what reading that book must have done for their morale; I can only guess, but I suspect that it inspired in them something of a will to fight on and face their fears. This is completely separate from the politics around our sad and current state of war and the reasons for it. There are few Leonidas’ in history.

I know I’ve written about this before, but Thermopylae has come to mind again as I’m reading a wonderful book by historian Michael Scott, entitled From Democrats to Kings: The Brutal Dawn of a New World from the Downfall of Athens to the Rise of Alexander the Great.

Scott’s book brings the world of ancient Greece after the Peloponnesian War into stark contrast with those days of honour and glory during the Persian invasion of Greece. It never ceases to blow my mind that a society (or polis, people, cultural group etc.) can achieve such magnificent glories, pleasing to the gods themselves, and then proceed with ease to piss it all away.

The make matters worse, Athens, Sparta, and Thebes each in their own turn, for years after, went to the Persians, cap in hand, to ask for aid in fighting their fellow Greeks! If there were any veterans of the Persian wars left, they must have been shaking their aging heads in shame at what was happening around them.

Maybe that is another reason the battle of Thermopylae is still celebrated. Not only was it a strategic and symbolic victory, it was also a selfless act. It was simple, and it was true. Leonidas ignored the politics that threatened to hold him back, and marched to certain death.

Many will say that this simply doesn’t apply to them, for they’re not soldiers fighting in a war on some foreign field. True, granted, though for many today, that is a reality. However, some past events, deeds, transcend all else, including war, and are applicable everywhere. We all face our own struggles day to day, and must meet whatever it is we must meet on our own, on our personal battlefields.

For a youth, that battle might be the fear of exams or being bullied in school. For an adult, it could be facing that daily commute to go to a job that is anything but inspiring. It might be not having a job at all, or failing to achieve one’s dreams or goals. A new mother may fear yet another day inside with the same routine, over, and over and over again. A family too may be dealing with the looming spectre of an allergy or something worse. However small and insignificant these things may seem, they are our own battles, fears, and it’s crucial that we fight on daily.

No doubt that Leonidas and his men each wrestled with some measure of fear, perhaps of loss, of not being remembered, of failing their way of life. But they overcame their fears, and though they died, they raised the bar of human achievement to heights we can only now dream of, but for which we should never cease to aim. And now, they grace our canvases, our screens, and our pages.

In closing, let the words etched upon the memorial stone at Thermopylae echo in our minds…

Ω ΞΕΙΝ ΑΓΓΕΛΛΕΙΝ ΛΑΚΕΔΑΙΜΟΝΙΟΙΣ ΟΤΙ ΤΗΔΕ ΚΕΙΜΕΘΑ ΤΟΙΣ ΚΕΙΝΩΝ ΡΗΜΑΣΙ ΠΕΙΘΟΜΕΝΟΙ

‘GO TELL THE SPARTANS PASSERBY,

THAT HERE OBEDIENT TO THEIR LAWS WE LIE’

Inspiring!

Thank you for reading.

Pythagoras’ Golden Verses – For a Good Life

There has been a lot of negativity in the news these past weeks, mostly directed at Greece and Greek people. Many comments, including from high-profile public personages, have been outright prejudiced.

Don’t worry. I’m not going to get into politics, who’s right, and who’s wrong, and how only the bankers seem to be winning anything.

Ok, I slipped there. Sorry.

With all the hatred and vitriol floating around the Web, I needed to go back to something uplifting, something ancient.

I went back to a bit of research I had done on Pythagoras and the Golden Verses. These are a series of seventy-one rules for living that were popular from antiquity and into the middle ages. It is presumed that these verses were what dictated the way of life for Pythagoras and his followers, known as Pythagoreans.

Most people today think of mathematics when they hear the name of Pythagoras, the Pythagorean Theorum having haunted many a youth in their school days, especially those not inclined to enjoy arithmetic. Myself included. I still shudder to think of it.

What many may not know is that Pythagoras was also a philosopher and mystic who influenced later philosophers, including Socrates and Plato.

Pythagoras was from the island of Samos which he left in c.531 B.C. to settle in Croton, southern Italy (then, Magna Graecia), where many ancient Olympic champions hailed from. In Croton, Pythagoras established a religious community. They believed in reincarnation and refused to offer sacrifices to the Gods, though they believed in and worshiped the Gods. If you think about that for a moment, that last point was pretty revolutionary for the time.

Pythagoras died in Metapontum (in modern Apulia, Italy) in c.497 B.C., and from then the Pythagoreans spread throughout the Greek world to spread his teachings, the Golden Verses among them.

The list of Golden Verses is quite long so I won’t list them all here. To read the entire list, check out this Wikipedia link.

To offset the negativity that seems to plague the world of late, I thought I would share a few of Pythagoras’ Golden Verses that stand out to me.

1 – First worship the Immortal Gods, as they are established and ordained by the Law.

5 – Of all the rest of mankind, make him your friend who distinguishes himself by his virtues.

7 – Avoid as much as possible hating your friends for a slight fault.

11 – Do nothing evil, neither in the presence of others, nor privately;

12 – But above all things respect yourself.

13 – In the next place, observe justice in your actions and in your words.

18 – Support your lot with patience, it is what it may be, and never complain at it.

19 – But endeavour what you can to remedy it.

20 – And consider that fate does not send the greatest portion of these misfortunes to good men.

27 – Consult and deliberate before you act, that you may not commit foolish actions.

32 – In no way neglect the health of your body;

33 – But give it drink and meat in due measure, and also the exercise of which it needs.

35 – Accustom yourself to a way of living that is neat and decent without luxury.

40 – Never allow sleep to close your eyelids, after you went to bed,

41 – Until you have examined all your actions of the day by your reason.

42 – In what have I done wrong? What have I done? What have I omitted that I ought to have done?

43 – If in this examination you find that you have done wrong, reprove yourself severely for it;

44 – And if you have done any good, rejoice.

66 – And by the healing of your soul, you will deliver it from all evils, from all afflictions.

69 – Leave yourself always to be guided and directed by the understanding that comes from above, and that ought to hold the reins.

There you have it. A bit of wisdom whispered to us across the ages. Whatever we glean from Pythagoras’ words, we can be sure that a life lived with kindness, charity, introspection and honesty is indeed a good life, and something to be grateful for.

Thank you for reading.

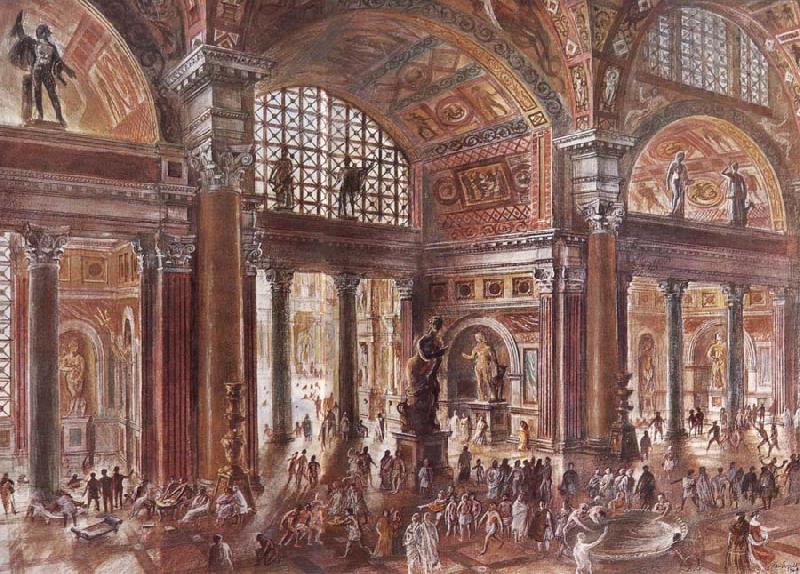

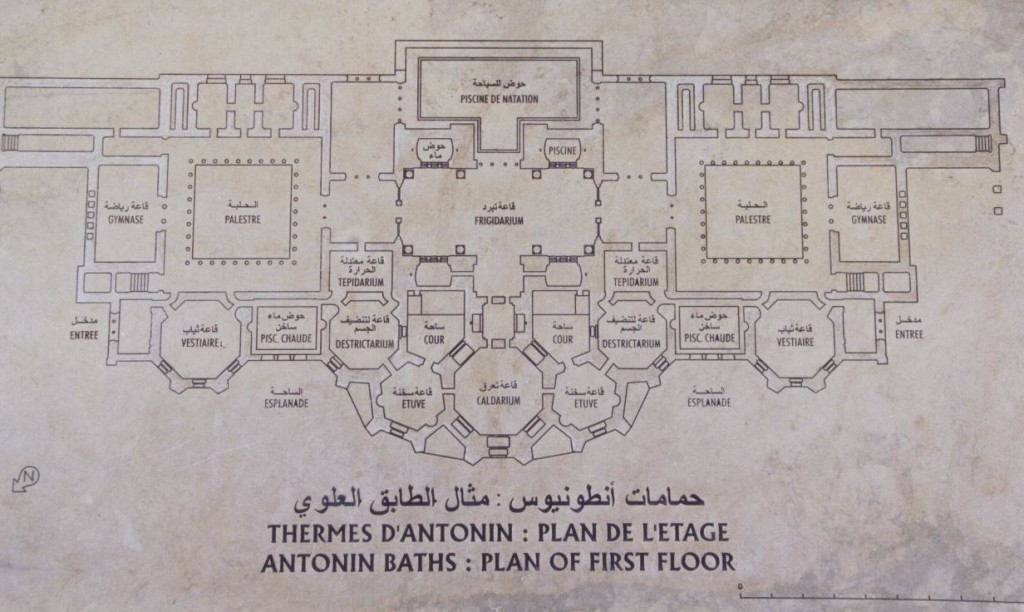

Ancient Everyday – Time for a Bath

Showering, bathing and generally keeping clean is something that we take for granted today. For most people, washing is part of the daily routine.

If you look at the Middle Ages, this was not the case. In fact, medieval people were pretty filthy. This isn’t surprising as bathing was considered a sin by many.

This wasn’t the case for ancient Romans, thank the gods.

As we do today, the Romans bathed and washed regularly, and as with going to the toilet, bathing was yet another very social activity for Romans.

Throughout the Roman Empire, public and private baths were common, owing something to the situating of bath houses over hot springs, and their ingenious use of aqueducts which brought water into the cities over great distances.

Baths and bathing complexes, of course, varied widely in size and the level of sophistication, whether the small pools and tubs of private balneae, or the massive imperial complexes called thermae. Whatever the size, there were some common attributes to most public baths across the Empire.

The Apodyterium

This was a sort of changing room where visitors to the baths would undress and leave their clothes in niches in the walls, not unlike today. Slaves were in attendance to give out towels and take care of your items. However, not unlike today, theft was common in the apodyterium, so wealthier patrons brought their slaves along to carry their possessions for them.

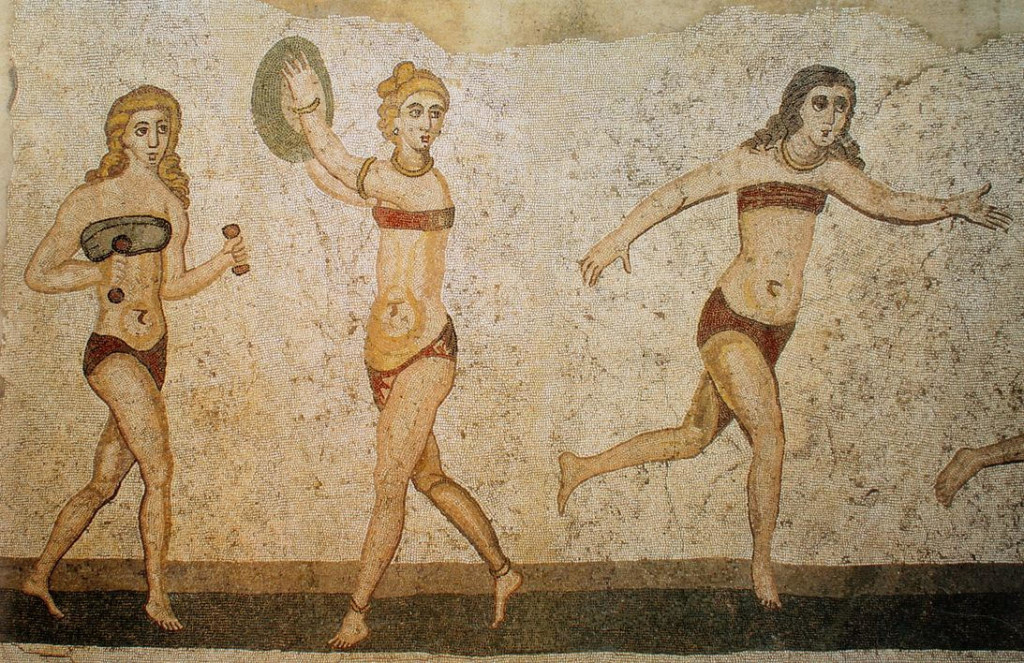

The Palaestra

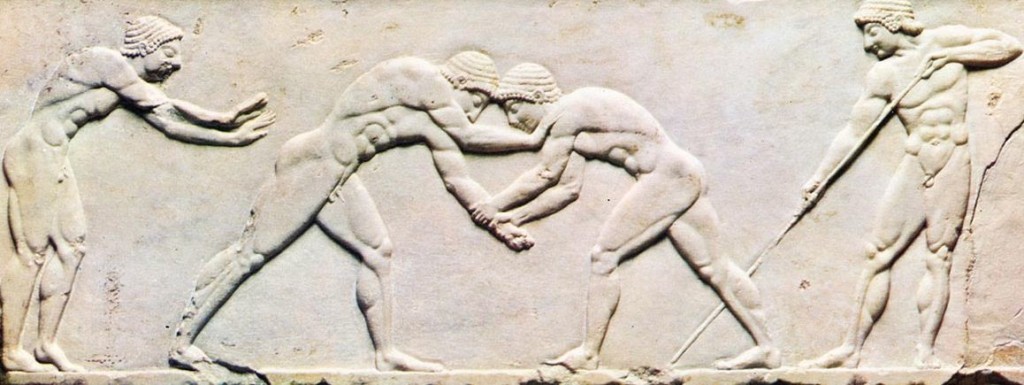

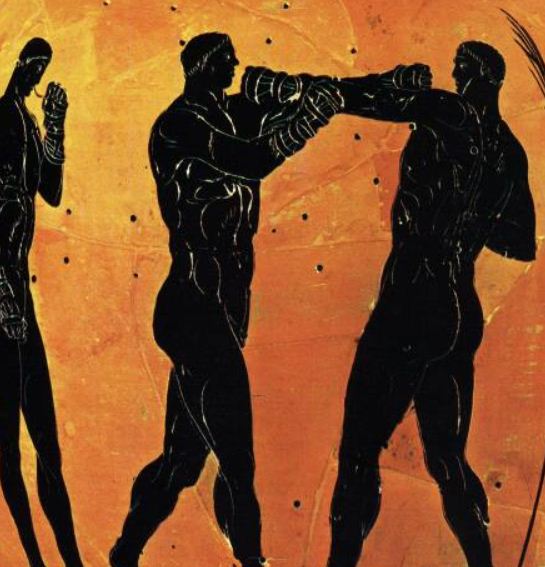

The palaestra was the workout area where some patrons would exert themselves before going into the baths themselves. Just as people hit the gym today, so the Romans exercised on the sands of the palaestra by wrestling, boxing, lifting stone or lead weights, and other activities. The scene here would have been one of competition, of grunting, and sweating. It could get pretty loud, as attested to by the Roman Seneca:

“I live over a public bath-house. Just imagine every kind of annoying noise! The sturdy gentleman does his exercise with lead weights; when he is working hard (or pretending to) I can hear him grunt; when he breathes out, I can hear him panting in high pitched tones. Or I might notice some lazy fellow, content with a cheap rub-down, and hear the blows of the hand slapping his shoulders. The sound varies, depending on whether the massager hits with a flat or hollow hand. To all of this, you can add the arrest of the occasional pickpocket; there’s also the racket made by the man who loves to hear his own voice in the bath or the chap who dives in with a lot of noise and splashing.” (Seneca in AD 50)

But the palaestra was not just for men. In ancient Rome, women too were permitted to exercise and stay fit. One famous mosaic shows a group of women engaged in exercise on the palaestra floor, though this was probably done at a different time, or in a separate area from the men.

The Tepidarium

After the exertions of the palaestra, patrons would then move to the first room of the baths proper, the tepidarium. As the name implies, this was the ‘warm’ room where one could begin to heat up and start sweating. In some cases, the tepidarium had a warm water bath in which bathers could submerse themselves, but in other instances, it was just a room of warm air, thanks to the underground, and in-wall heating from the system of hypocausts that were used to heat the baths.

The tepidarium was often highly ornate too. Men and women could lounge and talk business, gossip or anything else while being rubbed down with oils which the Romans used instead of soap. Once they were warm enough, and the oils had started to go to work on their pores, bathers moved to the next room.

The Caldarium

The caldarium was the hottest room in the bath complex, located as it was directly above the hypocaust furnace. This was the equivalent of the modern sauna where patrons would be more still, sweat, and scrape the mixture of oil and dirt from their skin with a tool called a strigil.

The caldarium had a basin with cold water for patrons to wet themselves with, but also a hot pool if they wanted to soak some more. The heat from the caldarium is what brought the dirt to the surface and aided with the cleaning of their bodies in concert with the oil that was rubbed on.

The Frigidarium

After the tepidarium and caldarium, it was time to close the pores and revive, and what better way to do this than by jumping into a cold pool of water.

Welcome to the frigidarium! One can imagine the echo of people’s squeals as they landed in the cold water, the shock running through them in a great wake-up call. Some of the larger bath complexes would also have included a swimming pool at this stage, in which patrons could swim a few laps.

The frigidarium was not a room patrons would spend too much time in. Who would want to when the next step is so enjoyable?

Massages, Food, and more Socializing

After having made his/her way through the various rooms of the bathing complex, many Romans would opt to get a massage. Either they had their own slaves oil them again and work away at their muscles, or they would have one of the bathing complex’s massage slaves work on them.

What better way to work out the knots owed to debates in the Senate house, fights on the battlefield, haggling in the imperial fora or other activities than to have fragrant oils massaged into your newly cleaned skin.

I tell you, the Romans knew what they were doing with this ancient toilette ritual! I’m relaxed just thinking about it.

After the massage, and dressing again in the apodyterium, some of the larger complexes had tabernae attached where patrons could go and eat, have a drink, gamble a bit at games, and most importantly, socialize.

That’s the interesting thing about public baths in the Roman Empire; they weren’t just facilities intended to curb public health issues by keeping the populace clean and hygienic, they were also the community centres, or community hubs, of the ancient world.

They were a bit of an equalizer too. In the Colosseum or Circus Maximus, the rich might have had the better seats with cushions, but in the thermae of the Empire, when naked, everyone was standing on equal footing.

So, next time you visit your, gym, local pool, or community centre, remember that you are participating in a highly social activity, owed mainly to the ingenuity of the Romans.

Thank you for reading.

For a bit more information, check out the video below from the series What the Romans Did for Us, with Adam Hart Davis. In this episode, he looks at Roman baths among other things related to Roman luxury!

Tiryns: Mycenaean Stronghold and Place of Legend

This week, I wanted to leave behind the sad and depressing subject of the destruction of heritage to write about a site steeped in myth and legend – Tiryns.

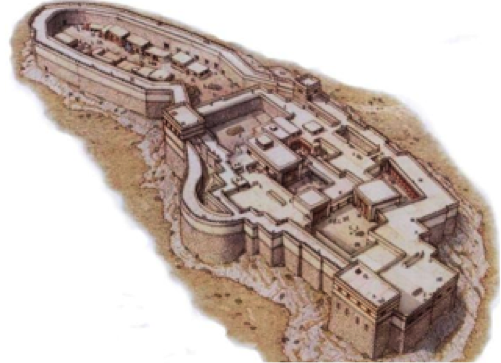

“In the south-eastern corner of the plain of Argos, on the west and lowest and flattest of those rocky heights which here form a group, and rise like islands from the marshy plain, at a distance of 8 stadia, or about 1500 m. from the Gulf of Argos, lay the prehistoric citadel of Tiryns, now called Palaeocastron.” (Heinrich Schliemann; Tiryns; 1885)

I visited the site with family during the summer of 2002. It was a scorcher of a day and the cicadas were whirring full force by 9 a.m. Luckily, the heat meant that the place was devoid of visitors – the perfect time to explore.

Tiryns is one of those sites that you likely know about if you’ve studied classics, mythology or archaeology. Most people haven’t heard about it. It lies in the broad Argive plain, a fenced-in circuit wall along the road between Nafplio and Argos itself, surrounded by orange and olive groves.

At first glance, there is no hint that Tiryns was one of the major Mycenaean power centres of the Bronze Age. The cyclopean walls are big, impressive, but there have been times when I drove by and didn’t even notice it. Perhaps that was due to the madness of driving in Greece.

When we got out of the car, the hot wind whipped across the plain to envelope us and, once we paid our entrance fee at the small kiosk, it seemed to sweep us up the ramp to the citadel, and back in time.

Tiryns is a place of myth and legend. It’s been inhabited since the 7th millennium B.C., but by the Hellenistic and Roman periods, it was already in the death throes of a swift decline. Pausanius visited as a tourist in the 2nd century A.D.

“Going on from here [from Argos to Epidauros] and turning to the right, you come to the ruins of Tiryns… The wall, which is the only part of the ruins still remaining, is a work of the Cyclopes made of unwrought stones, each stone being so big that a pair of mules could not move the smallest from its place to the slightest degree. Long ago small stones were so inserted that each of them binds the large blocks firmly together.” (Pausanias; Description of Greece)

I’ve spoken before about the feel of a place of great antiquity. Tiryns is a truly ancient place.

In mythology, it was founded by Proitos, the brother of Akrisios, King of Argos and father of Danae, the mother of Perseus.

It was said that the walls of Tiryns were built by the Thracian Cyclopes of the ‘bellyhands’ clan before they built the walls of Mycenae and Argos. This is why this style is called ‘cyclopean walls’. They were known as the ‘bellyhands’ because that clan of the Cyclopes were said to have made their living through manual labour.

It would have been a feat of tremendous strength to say the least, as each stone weighs several tons.

The association with Perseus is indirect as he acquired Tiryns after he killed his grandfather, Akrisios, but before he established Mycenae.

One of the most important mythological associations with Tiryns, however, is with Herakles, son of Zeus and Alkmene. The latter was the granddaughter of Perseus.

Let us go back to the time when Eurystheus was king of Mycenae, Tiryns and Argos (Note: Eurystheus was not a king of Athens, as portrayed in the recent film, Hercules.)

According to Apollodorus:

“Now it came to pass that after the battle with the Minyans Hercules was driven mad through the jealousy of Hera and flung his own children, whom he had by Megara, and two children of Iphicles into the fire; wherefore he condemned himself to exile, and was purified by Thespius, and repairing to Delphi he inquired of the god where he should dwell. The Pythian priestess then first called him Hercules, for hitherto he was called Alcides. And she told him to dwell in Tiryns, serving Eurystheus for twelve years and to perform the ten labours imposed on him, and so, she said, when the tasks were accomplished, he would be immortal.”(Apollodorus; Book II)

After Hera drove Herakles mad, causing him to kill his own children, the Oracle at Delphi told the hero that he needed to serve King Eurystheus to atone for his horrible actions.

Herakles settled in Tiryns. His twelve tasks, or Labours, for Eurystheus are legendary and have been depicted in art for centuries throughout the ancient world. You can read a previous post about the triumphs of Herakles HERE.

Admittedly, when I visited Tiryns I had no idea of its associations with Perseus or Herakles. For me, a lot of research is sparked after visiting a site, and as a result, a follow-up visit is certainly in order.

The citadel of Tiryns is about 28 metres high, 280 meters long, and it was built in three stages. In the 12th century B.C. it was destroyed by earthquake and fire but remained an important centre until the 7th century B.C. when it was a cult centre for the worship of Hera, Athena, and Herakles.

The Late Bronze Age (1600-1050 B.C.) was the height of Tiryns’ existence. It’s during this time that the cyclopean walls and most of the fortifications were built.

Today, as in the Bronze Age, one approaches the citadel on the east side. To get to the upper citadel, which was the location of the great megaron and palace, you must walk up a massive ramp that is 47 metres long and 4.70 metres wide. This would have led to the main wooden gates.

Once past the gates, you walk along what was a corridor that led to the Great Gate which was flanked by a tall tower. The Great Gate was almost the size of the famous Lion Gate of Mycenae, and would have proved an imposing structure.

When I was walking along the ramp, looking up at the remains of the massive walls and the tower, I could imagine warriors in bronze, with boar’s tusk helmets, looking down on me, with spears or bows in hand.

Even though the citadel contained a luxurious palace and baths, this would not have been an easy fortress to storm.

Once you attain the top, you find yourself on a level area looking out over the site – the upper, middle and lower citadels.

There is not much left in the way of intact walls when it comes to the palace but you can see the outlines of the many rooms, especially the courtyards and the great megaron where the King of Tiryns held court and had his throne on a raised platform overlooking the central hearth.

Imagine Herakles approaching Eurystheus to ask him what his next labour was to be, in this room. This was the heart of the palace. Other rooms would have included residences, a second megaron and even a bath, the floor of which is made up of a huge monolith.

I was a bit dazed, standing there in the heat, looking on the remains of this site with awe. It’s so very old and the ruins only hint at what was a luxurious, but defensible, palace. And that was just the upper citadel.

The middle citadel, 2 m lower, provided access to the defences and may even have contained a pottery kiln. The lower citadel, which is also surrounded by walls, may have been used as a refuge for the people of Tiryns town on the west side, in times of need.

At one point, when I was looking about the gravelly surface of the court, I spotted tiny bits of pottery. Of course, I bent down to get a closer look and picked up a shard with three black lines painted across it. Before I could contemplate the age of this piece, a loud whistle blew and a site person seemingly emerged from the rocks like an asp hiding from the midday sun. “No touching!” I heard, in heavily accented English.

Good thing she didn’t have a spear or bow.

After leaving the upper citadel, we walked down some steps to what is my favourite part of the site – the east galaria.

This beautiful arched tunnel is still intact, and with the sun shining from above, it was suffused with soft light. I immediately imagined a Mycenaean queen strolling between the light and shadow of this place, or a determined king on his way to a war council, his cloak flapping behind him, bronze-clad guards in his wake.

Such is the power of a site like this to fire the imagination.

Back to the present.

It’s funny, but whenever I find myself fed up with cold winter days where I live, I think back to that scorched but brilliant day at Tiryns, and smile. I feel warmth again. I enjoy the glint of the sun radiating off of the stone, and its sparkle far out in the Gulf of Argos.

This ancient citadel is a welcoming place where history and myth are entwined, comfortable allies. I certainly hope my path leads me there again one day soon.

Thank you for reading.

What is your favourite ancient site with mythological and legendary links?

Let us know in the comments below.

Preserving the Past – Some Thoughts on the Importance of Historic Places

I’m talking about something a bit more personal for this post.

Recently, I went back to my home town with my family. We were in the area and so we thought it might be fun to take a drive through the old neighbourhood.

It’s kind of weird passing by primary and secondary schools where you spent so much time, and then happily pushed them from your mind. All that feel like another life.

Our last stop was the last house my family owned. It was the oldest house in the area (over 100 years old), and belonged to the original landowner who had settled the area. This is a picture of the house:

As we were driving along the street, beneath the tall trees, we watched the modern monstrosities as we passed by, those huge, thinly-walled modern mansions that people seem to be so eager to throw up.

I found myself thinking, ‘Man, oh, man, we were so lucky to live in that solidly-built, old house. So many memories –graduation parties, Christmases, dinner parties, engagement parties, etc. etc. It was a place that had seen the area grow up and mature all around it.

This is what we saw when we pulled up in front of the house:

That left us winded and wondering simply, ‘Why?’

So that another monster home could be built? I guess. And yes, I know, the house was no longer ours. It was really none of our business any more.

But this shocking experience got me to thinking beyond this personal experience…

If the destruction of one small house, lived in by only a handful of families over the last hundred-plus years, can deliver such a blow, how much greater the loss when other historical monuments around the world are wiped out?

It happens every day, everywhere, from small towns and villages, to cities, to world heritage sites that represent pinnacles of human achievement.

The period doesn’t matter. What matters is that history, and more importantly, the voices of history, are being silenced when these cultural atrocities are carried out.

I’ve worked in the area of heritage preservation, and in my office there are a lot of people who are passionate about the subject. But they’re facing an uphill battle, as are preservationists around the world, historians, archaeologists, restorers and more. All of them.

The thing is, I do believe in the memory of place. History is about the human stories of everything around us, and those voices of the past need to be listened to, deserve to be listened to. They have much to teach us.

If we allow the destruction of an historic temple, farmstead, theatre, or market, even a house, we are losing yet another piece of our collective history. We lose yet another potential lesson and opportunity to better ourselves.

There has been a lot in the press recently about the destruction of historic sites in the Middle East, namely the ancient sites of Nineveh, Nimrud, and Hatra (about which I wrote HERE). And now the ancient city of Palmyra is hanging over the precipice…

These are just a few examples of the destruction that has been wrought of late. If you go the UNESCO World Heritage website, you can look at the list of endangered world heritage sites. It’s sad, it’s upsetting, and it’s happening all the time.

We are so eager to move into the future that we often forget the past, opting to tear down a sturdy brick building that has been there for one or two hundred years, in favour of putting up yet another glass condominium that won’t even make it to sixty years without falling apart.

Think about it, people pay thousands of dollars to travel across the ocean to visit places like England, or France, Greece and other countries so that they can, in most cases, visit ‘old’ places, historical sites.

If those physical, historic spaces and places were not there, the voices of the people who had inhabited them would be more or less silent to us. We can read someone’s words, but to walk in their footsteps with their thoughts and words echoing in your mind is an entirely different experience.

There are varying degrees of importance and different perspectives, true, but all the voices of the past matter, as do the things they created.

When I look at that picture of the patch of mud where our one-time house used to be, I’m sad, not just for me, but for the neighbourhood which has lost a small chunk of its history.

To most people, the house was neither here, nor there. But just because a place is meaningless to some, doesn’t been it isn’t of import to others or the community as a whole, be it down the street in your own neighbourhood, or on the other side of the world.

When the physical places are treated with disregard, it’s the beginning of the process of forgetting… which goes on… until… nothing… is… left……..

What do you think of this topic?

Next time you walk or drive around your neighbourhood, check to see if there are any historic or ‘old’ places that catch your attention? Imagine how the neighbourhood would change if that place were completely wiped out.

Tell us in the comments about an historic or ‘old’ place that is close you, a place that means something to you.

Thank you for reading.

The Links Between History and Mythology – A Guest Post by Luciana Cavallaro

Today I have a special guest on the blog.

Luciana Cavallaro is the author of a series of mythological retellings from the perspectives of some fascinating women in Greek myth.

When I read her book, The Curse of Troy, I knew that I wanted to have her write a guest post for Writing the Past. Luciana has a wonderfully unique style, and she gives these accursed women of Greek myth a voice that you may not have heard before.

So, without further ado, a big welcome to author, Luciana Cavallaro!

First, I’d like to thank Adam for inviting me to be a guest blogger. I’ve been following Adam’s blog for years now and enjoy reading about the Roman history, expansion and legacy they’ve left behind and learning about King Arthur and Medieval England. The latter is not one of my strongest or favourite periods of history, but I do enjoy reading Adam’s articles. I also want to apologise to Adam. He asked me last year to be a guest blogger and at the time I was finishing up my book and then time got away from me.

Let’s get into it

I’m a bit of a fan of mythology, in particular Greek myth, but I’m not an expert or purport to be one. I love the stories, learned a great deal from them and continue to do so. What I particularly enjoy are the links between the myths and historical fact.

Before I get into that, let’s address what mythology is. Here’s a dictionary meaning:

Mythology is a body of myths, especially one associated with a particular culture, person, etc. (Collins Concise Dictionary, 1989)

I prefer Joseph Campbell’s explanation:

There is a mythology that relates you to your nature and to the natural world, of which you’re a part. And there is the mythology that is strictly sociological, linking you to a particular society.

(Interview with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth, 1986)

Myths are cultural as is history. If one digs (pardon the pun) deep enough, there is a correlation between the story and fact. Let’s take Jason of the Argonauts and his search for the Golden Fleece. In the Republic of Georgia, once annexed by Russia, the fleece of a sheep was used to trap golden grains dug from the river, or placed in the river banks and used in the same way.

Here’s a great article on this: Legend of the Golden Fleece was REAL: Greek myth originated near the Black Sea where miners used sheepskin to filter gold from mountain streams, geologists claim

I also watched a documentary of an Australian photo journalist who was trying to find the cities Alexander the Great founded in the Middle East. He watched Afghan miners use this technique to find gold in the riverbeds 4000 years on.

The journey from Jason’s home of Iolkos (Thessaly) to Georgia some distance away was dangerous. It is possible the story of the skills and craftsmanship of the Colchians who developed smelting and casting metals for agriculture and making jewellery found their way to Greece. This was something the ancient Greeks wanted, and the gold.

“Jason Pelias Louvre K127” by Underworld Painter – Marie-Lan Nguyen (2006) Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

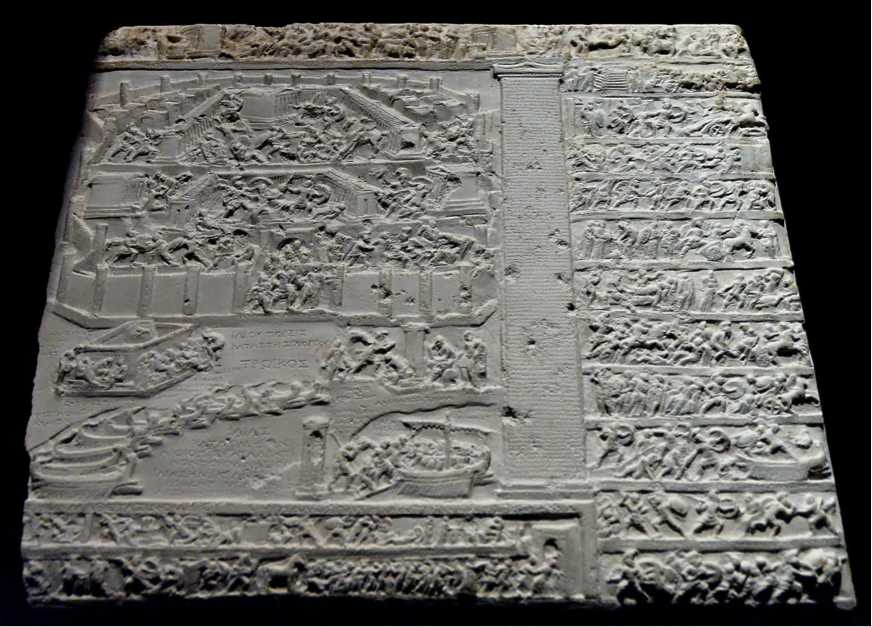

Another is the great story of Troy in Homer’s Iliad, which is a famous tourist site, and I did get to see. It is massive just as Homer stated. The lofty walls the Greeks couldn’t penetrate are there, and what is left is tall and slopes inwards. Hittite texts confirmed the site of Ilios, which they called Wilusa and identified Alaksandu/Alexander as one of the city’s kings. Alexander was the Greeks’ name for Paris. The texts also mention an invading force from the west, Ahhiyawa, that closely resembles Homer’s name for the Greeks, Achaeans. What historians have concluded is Homer’s story is a collective memory of the various invasions on Troy over centuries and its eventual downfall.

Hittite tablet recounting the events of the fall of Troy by Unknown – Jastrow (2006). Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The fact that the site of Troy exists, as does Mycenae, home of King Agamemnon, does give credence to the mythologies. But like all stories, you can’t let facts get in the way of telling a good tale.

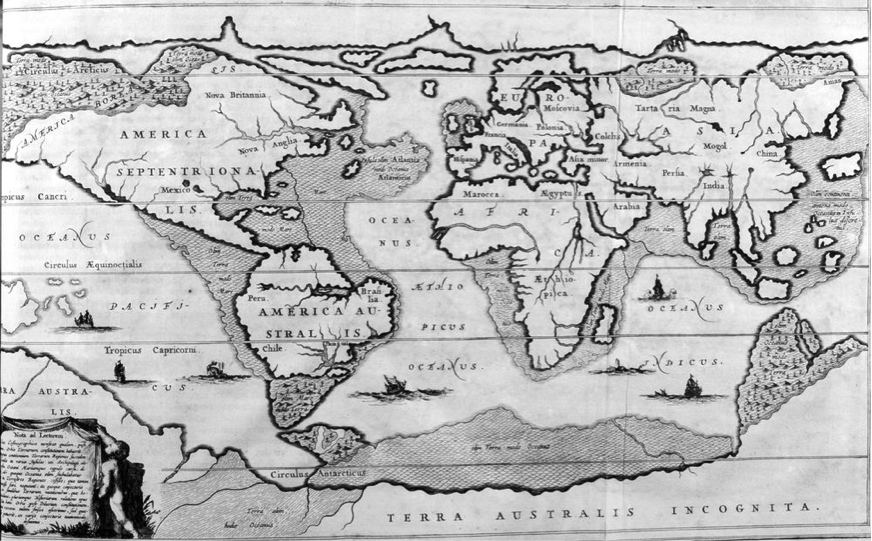

I do believe the more we delve into the myths, the more facts we’ll find in history. As with the current series I’m writing on my blog Eternal Atlantis, on the Atlantis myth, I believe such a place did exist. Like Homer’s Iliad, the enduring legend of Atlantis is a conglomeration of memories and oral histories to explain the rise and fall of a mighty empire. Look through the timeline of history and you will find many periods of great empires and their demise, either through war or a natural disaster.

Kircher’s 1675 map of the world after the Great Flood. The location of Atlantis is marked in the Atlantic Ocean. (Print Collector/Getty Images)

Myths, like all stories, have morals and a message to relate. One day, I hope we will be smarter and take heed of these so we don’t keep repeating these transgressions. In a hundred or thousand years to come, people will question our mythology. What mythology will we leave behind?

I’d love to know your thoughts on the veracity of myths in our history.

I’d like to thank Luciana for taking the time to write this fascinating post for us. I’m so jealous of her trip to Troy, a place which I have wanted to visit for a long time. Ah, someday…

Mythology is truly fascinating, and there is a lifetime and more of stories for us to enjoy and learn from.

If you enjoy mythology as much as I do, you’ll definitely want to check out Luciana’s book, Accursed Women, or pick up one of the many short stories she has out. She also has a new book entitled Search for the Golden Serpent which I’m looking forward to reading.

Also, be sure to sign up for her E-bulletin so that you can receive her very interesting blog posts to your e-mail. By signing up, you’ll receive The Curse of Troy for FREE!

I always look forward to reading her posts as they are a fantastic escape from the everyday. The blog series on Atlantis is titantic!

Please leave any questions or comments for Luciana in the comments below, and, once again, thank you for reading…

A Head for War – Top 10 Ancient and Medieval Battle Helmets

Some of the very first things that interested me in history as a young boy were weapons and armour.

Boys will be boys, and so it’s no surprise that this is what drew me into the ancient and medieval worlds in the first place.

I remember getting a used book called The Art of Chivalry, which I flipped through over and over again. I was mesmerized by the images of broad swords and gothic armour, the shields, the lines, and the hack marks from various battles.

If there is one piece that has been common to most ancient cultures, it’s the helmet.

Apart from Celtic warrior heroes, most soldiers and fighters wore a helmet into battle. However, despite the common usage of something to protect the head and face, the styles varied greatly over the ages, making for some magnificent pieces that were utilitarian and beautiful at the same time.

So, here is my Top 10 list of favourite ancient and medieval battle helmets…

The Trojan War

#10 – Mycenaean Boar’s Tusk Helmet

My tenth choice on this list is one that you might not have expected to see. It isn’t made of iron or bronze, but rather of boar’s tusks that would have been sewn together over a skull-cap, or lining of some sort.

We’ve all heard about the Trojan War, but the portrayals of Greeks and Trojans wearing Classical Age Corinthian Helmets is not exactly accurate. We’re talking about the (approximately) 12th century B.C. here. This is a helmet of great antiquity that was worn by the heroes who fought beneath the walls of Troy in this most famous of wars.

I’ve put it on this list for sheer interest’s sake.

See You in the Lists!

#9 – Jousting Helmet

If gladiators were the entertainment of the Roman world, jousting was the equivalent of the Middle Ages.

From the time I was a boy, this is what I was drawn to. Two knights in armour careening toward each other with their lances couched. I could see their horses’ trappings fluttering as they came closer and closer and then the tremendous impact of splintered lances and shattered shields.

Fantastic! But wow, so dangerous. Tourney knights may have donned colourful ribbons and head dresses for the tilt, but they were certainly not wussies. These guys were tough as nails!

And they did this with little to no visibility! The tourney helms were thick and heavy, and were intended to deflect a lance point at speed. It must have been absolutely suffocating inside one of those.

But how imposing they looked, how fantastic with the colourful tourney crests affixed on the top. These guys took the tourney circuit, and the ladies, by storm, all in a chivalrous way, or course. Men such as William Marshall or Ulrich von Lichtenstein (not Heath Ledger, the real one!), made a name for themselves in the European lists and helped to shape the chivalric ideals we see in art and story.

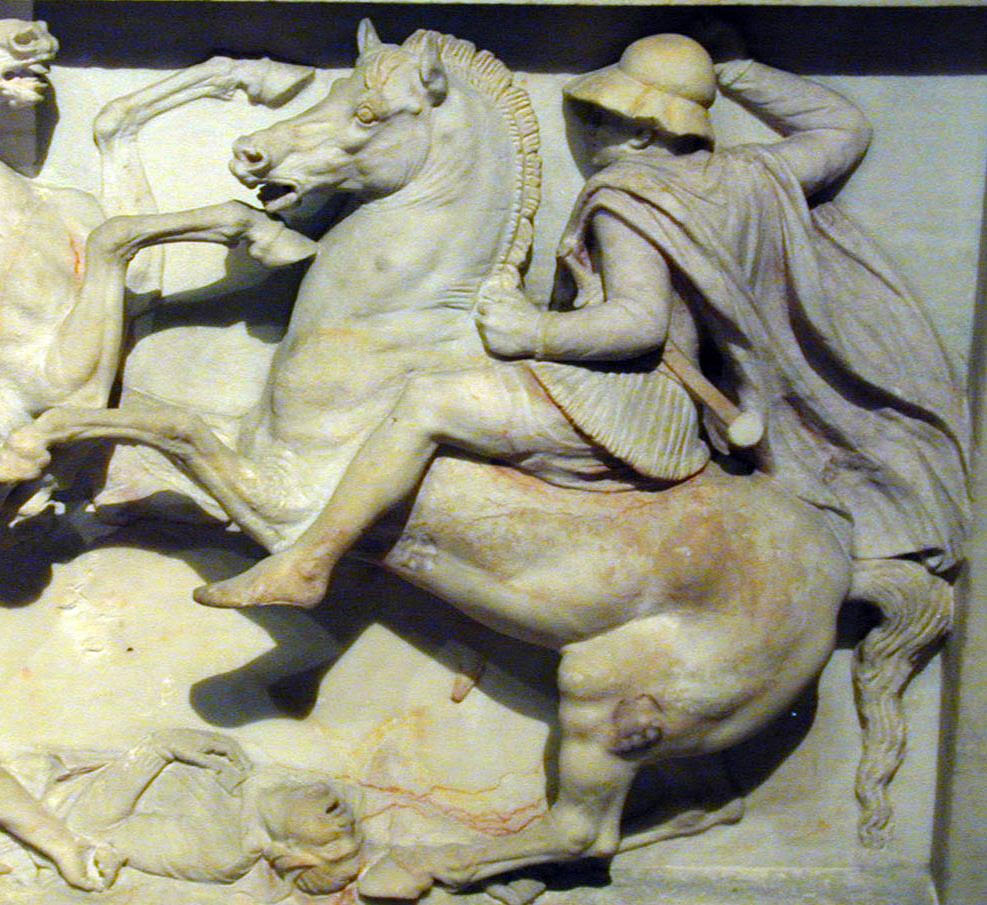

Riding with Alexander the Great

#8 – Hellenistic Cavalry Helmet

When you get to the time of Alexander the Great and the successors, they begin to add a bit more pizazz to their headgear. Alexander would have had special helmets outfitted just for him, perhaps made to look like a lion head which you can see on the coins (remember, the Argead dynasty claimed descent from Herakles!), or the ram horns of Zeus-Ammon.

My eighth pick would be the helmet commonly used by the Alexander’s Companion Cavalry, commonly thought to be the best cavalry in the ancient world. Being one of these guys was glamorous and carried a lot of cache. They wore a Boeotian-type cavalry helmet with embellishments such as laurels and other ornamentations. It was also a sort of armoured sun-hat, perfect for charging across the plains of Asia in summer.

But don’t let the fanciness fool you, the Companions were crack heavy cavalry troops, and fierce enough to help Alexander bring down the mighty Persian Empire.

The Battle of Hastings

#7 – Norman Conical Helmet

1066 is a year that many of you will be familiar with. This is the year that William the Conqueror and his Norman army invaded England and killed the last Saxon King, Harold, at the Battle of Hastings. The Normans changed the face of England, some might say not for the best.

But they were a fighting force to be reckoned with. And their arms and armour reflect a more functional, militaristic culture that is immortalized in the Bayeux Tapestry.

When I think of the Normans, I think of kite shields, chain mail, and of course the conical helmet. This may not be the most dashing or even protective of warlike head gear, but its silhouette is unmistakably Norman. It was basically two bits of steel held together by a spine with a big nose guard. That’s it. There was no neck protection unless chain mail was attached to the lower rim, and the face was exposed apart from the nose. It would have had great visibility and some deflective traits because of its pointed shape. It would not be my pick for personal use, but I’ve included it because there’s just something about it.

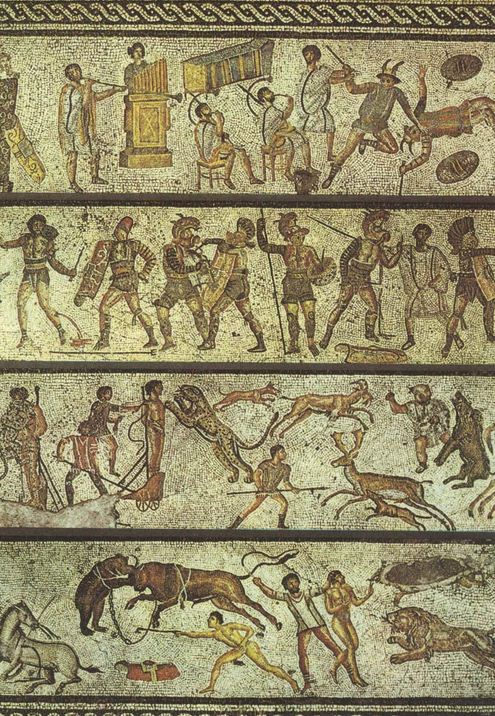

Gods of the Arena

#6 – Murmillo Gladiator

The Romans didn’t just like violence on the battlefield. They also enjoyed it on a Saturday afternoon, just for fun!

Some of the most enduring images of ancient Rome that we have are of gladiatorial combat in the amphitheatre. Gladiators were slaves, but they were also showman, and some reached unprecedented heights of popularity, almost as high as the charioteers of Rome.

Because it was a show, the gladiators played the roles of mythological beasts or ferocious, long-defeated enemies from past campaigns. But they didn’t wear masks, they wore elaborate helmets. My favourite gladiatorial helmet is the Murmillo, which was meant to represent a sort of sea creature, paired off against a Thracian warrior, or Thraex.

The Murmillo helmet was big and could be very elaborate with mythological or battle scenes embossed on it. This was an ornate, but heavy-duty helmet that was meant to inspire awe and take some heavy hits. During the early Empire, the Murmillo and Thraex were the most common pairing in combat. When they clashed, you can bet the crowd was baying for blood!

The Cross the the Crescent

#5 – Medieval Great Helm

The Crusades figured largely in my study of medieval warfare, and so it’s no surprise that the one helmet from the time that should be included here is the medieval ‘Great Helm’.

This cylindrical helmet would have been worn over a chain mail headpiece, or coif, and was the standard for most knights going on Crusade to the Holy Land. Designs by way of the puncture holes for breathing varied, but they were all big with narrow eye slits and cross-like seems on the face.

I really like the look of this helmet, but I can imagine that in the heat of Palestine, it would have felt like being in an oven. Furthermore, because the ears were covered, and because of the box-like structure of the Great Helm, the echo inside must have been insane in the thick of battle.

When I see this helmet, I also tend to think of Monty Python and the Search for the Holy Grail. ‘None shall pass!’

The Waning of the Middle Ages

#4 – Gothic Armour

Some of the most complete and beautiful armour ever comes from the late middle ages. Late medieval armour was, in large part, a reaction to new weapons technology, namely firearms.

This was really the last hurrah for full body armour and helmets that matched beauty with defensive intent. We know it as Gothic armour, and there are plenty of well-preserved examples in museums and castles around the world where you can get up close and personal with it.

There are many styles, but they all share one thing in common: they seek to encase the wearer as much as possible to protect against sword, mace, axe, arrow, and of course firearm shots.

Early firearms were notoriously inaccurate, but knights would have been extremely vulnerable when charging into the spray from a bunch of arm cannons. The English longbows at Agincourt and Crécy destroyed the French knights, and this just took things one unfortunate step further.

The Gothic age of helmets and armour in general is a bit of a swan song.

Warfare had changed and the sight of fully armed knights tilting on battlefields such as Bosworth was soon to become a thing of the past, a thing of romance. Perhaps it is fitting that this was some of the most beautiful, functional armour all rolled into one. It was indeed the end of an age, and well-deserving of number four on my list.

Ghost Warriors

#3 – Late Roman Cavalry Helmets

Now we come to it – the top three.

Whereas the men of the Legions had solid functional helmets when they went into battle, the cavalry alae of the Empire went in for something a bit more dashing and terrifying.

There is a lot of differentiation among the auxiliary units attached to the Legions because most of them were not Roman, and brought their own cultural style to the mix.

However, my favourite cavalry helmets are those with masks attached. They’re ornate on top, often with mythological scenes or beasts, and then have a mask of the same metal protecting the wearer but also striking fear into the enemies they were riding down.

There is some debate as to whether or not the actual masks were used only for demonstrations or parade, that they were perhaps removed for actual battle. But it’s not unlikely that they were indeed worn into battle. After all, some medieval helmets, as we shall see, provided much less visibility than a Roman cavalry mask.

These elite cavalry troops would have seemed like shades or furies as they rode into the fray, swinging a spatha and holding a howling draco standard. My solid number 3!

Men of the Legions

#2 – Roman Imperial Gallic Helmet

The Romans knew their warfare and their weapons. They also knew how to adapt, and how to adopt when they saw a good thing.

By far, my favourite Roman helmet has to be the Imperial Gallic helmet. If you look closely at the design, it makes perfect sense. They thought of everything – good vision and hearing for the legionary, protection for the back of the neck from downward slashes by those Celts, a visor in the front for the same thing, and massive cheek pieces that protected the side of the face without hindering vision.

This was a warrior’s helmet, and it was worn by tribunes, centurions, optios, and regular troops. A crest could also be attached depending on the rank of the person wearing it. But regular legionaries wore it without decoration and just went at it with the enemy in front of them. This is my pick for most utilitarian! It could easily take number one, but…

Grace in the Golden Age of Greece

#1 – The Corinthian Helmet

…I’m giving in to beauty.

When it comes to ancient Greece, the helmet that most people imagine is the Corinthian helmet. To me, this is a supremely beautiful helmet, my favourite for looks. It was used for several centuries, sometimes with a crest, sometimes without. These were made of bronze and would have been great at deflecting, spear thrusts, sword swings, and whizzing arrows.

I’ve tried on this helmet at re-enactor fairs and I must say that it’s very comfortable. Vision is decent, and it does indeed rest easily on the top of the head when not sweating it out in the shield wall. Hey, if it’s good enough for the goddess Athena, it’s good enough for me!

The one downside of the Corinthian helmet is that it would have been difficult to hear everything that was going on because there were no holes for the ears. Also, in the Mediterranean heat during the summer campaign season, it would have been hot!

But I still love the Corinthian helmet. For me, this is #1!

This could easily have been a much longer list. It was harder than I expected (but oh, so much fun!) to pick just ten. They are unique, utilitarian, and beautiful in their own ways, and so deserving of a place on the list, in my humble opinion.

I’ve always felt very strongly that the invention of gun powder was a low point in human and military history. It meant that any coward could pick up a gun and, from a distance, take down the most skilled, well-trained warrior without breaking a sweat. It meant that the scale of casualties would increase, and that is something we feel painfully to this day.

A lot of people might disagree with that. They might say that guns are the great leveller.

But somehow, in an age of cold black steel and bullets, I don’t really think we’ll hear about heroes like Hector or Achilles meeting face to face. Alexander won’t be charging King Porus’ elephant on Bucephalas any time soon. The Spartan shield wall is lost to history and the lists of medieval Europe are long silent but for a few scattered bands of Renaissance Festival enthusiasts.

But the art of war does remain, and it serves as a reminder of the past and the reasons for it.

Next time you are at a replica shop, re-enactor fair, or Renaissance festival, be sure to slip an ancient or medieval helmet replica over your head. You’ll be taking one step closer to understanding and feeling the past.

Thank you for reading.

What does your top 10 list look like? Do you have a favourite?

Let us know in the comments below…

Ancient Everyday – Getting Social with Sponges

Do you use a bathroom?

Of course you do! Everybody does. They might vary in design or level of fanciness, sure, but every person on earth, and throughout history, has had to do their business. And they usually have done in a certain spot, be it a bush, a hole in the ground, a pot, or some form of toilet.

And people, usually, have used something to clean their bits and pieces afterwards. Ok, maybe not so much in the Middle Ages (hygiene was less of a thing then), but certainly in the ancient world.

I’m not usually one for bathroom history, but when it comes to the Romans I have to admit that they had a good system going, that is, if you weren’t shy.

So, we’re taking a brief look at the Roman toilet and accoutrements of going to the loo in the Empire.

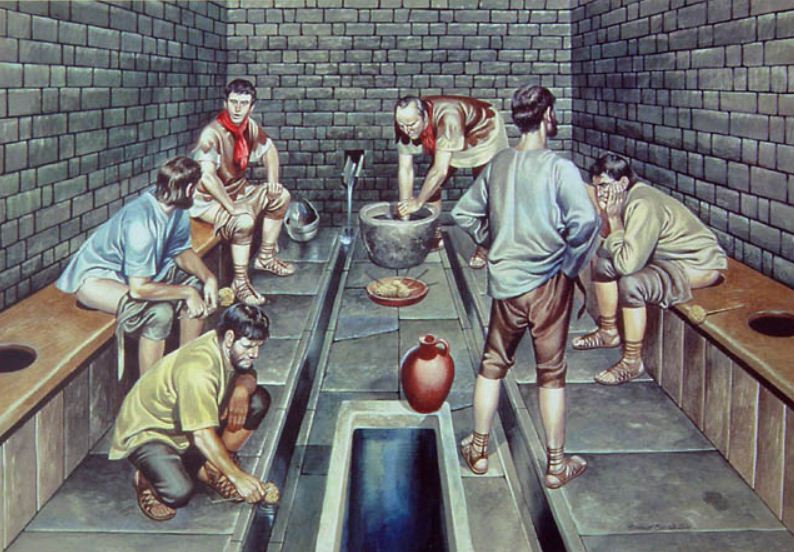

If you’ve ever travelled to Roman archaeological sites, you will likely have seen a long or square room with stone benches. Along the benches are a series of evenly-spaced holes, and on the floor before the holes, are carved channels.

Welcome to the public toilet, or Roman military latrine!

Today we like our privacy, of course, but in the Roman age, unless you were in your privy at home, you were doing your business alongside everyone else.

That’s right! If you used a public toilet, you would be sitting cheek-to-cheek with men, women, and even children.

Oh dear…

Not for the introverts among us, is it?

In ancient Rome, people would sit side-by-side on the benches, purging themselves and, if they weren’t having a tough time of it, would even chat things up and do business. Or they might even sit down and make notes on their tablet – the wax kind, of course. Perhaps some things haven’t changed so much!

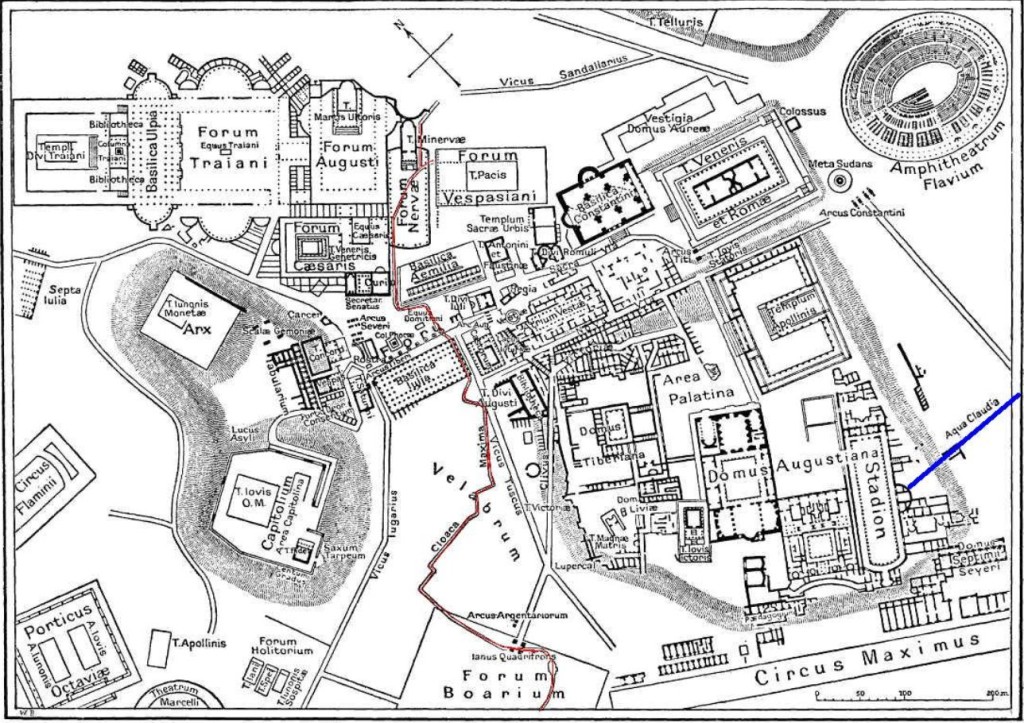

Setting aside the awkwardness of Romans’ social toilet behaviours for a moment, you have to admit that their sewage systems were the best.

Beneath the rows of communal toilet benches in public latrines, military bases, and the homes of richer Romans, fresh flowing water brought into the city by a system of aqueducts (11 of them in Rome!) ensured that waste water did not linger to create a stink. Once people did their business, it was flushed out by the main sewer system of Rome, the Cloaca Maxima. This ‘greatest sewer’ was originally built around 600 B.C. under the orders of King Tarquinius Priscus.

Pretty impressive, and important in a city that just grew and grew over the centuries.

Not all neighbourhoods were so lucky to have running water beneath their latrines if they had them. In those cases, people would dump buckets of waste water from on high, especially from the tenement block windows. The streets had channels in the middle so this waste would eventually be washed away.

Walking down some streets in ancient Rome would have been something of an ordeal.

But what about toilet paper? Today we take that for granted, but they didn’t have such a thing in ancient Rome.

Enter the spongia.

That’s right, sea sponges. Today we go on vacation to the Mediterranean Sea and buy great sea sponges to use in our baths back home. We covet them almost as luxury items.

In ancient Rome, these were used to wipe yourself after going to the toilet.

Here’s how it worked. You had a sponge that was on the end of a stick. When you finished doing your business, you took the sponge on a stick, wet it in the fresh water that flowed in that channel we spoke of on the floor in front of the toilet, and gave yourself a few back-and-forths until you were clean. When you were finished, you rinsed it.

This is where, to my modern mind, things got really dodgy. In a public toilet, there would be communal spongia for people to use. Ew!

That’s right, if you didn’t bring your own sponge on a stick, you used one that someone else had already used.

There is some debate as to whether a new sponge was used each time or not. I’ve read that sponges on sticks were re-used after a good rinsing (one hopes!), or that one simply stuck the communal stick into a fresh sponge and then dumped it into the hole you were sitting on.

I’m not going to ponder this anymore. I’ll leave that to you. Suffice it to say that a sponge that was simply poked with a stick would not really stay on the stick, would it? Especially when wet. I think it would have to be fastened to the stick to be of any use. Just my two cents on that.

So there you have it! Roman men and women getting social in the toilet while sitting cheek-to-cheek, and sharing sponges.

I do love the ancient world!

Thank you for reading.

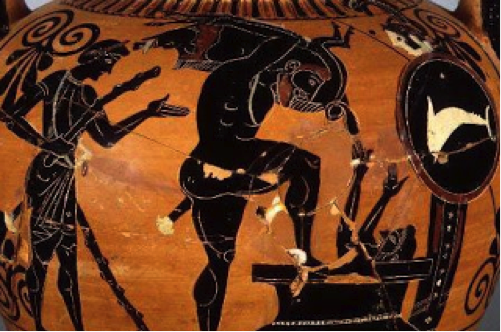

War without the Shooting – Sport and Strife in Ancient Athletic Competition

Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war minus the shooting.

(George Orwell, “The Sporting Spirit”, Tribune, 14 December 1945)

I was reminded of the above Orwell quote in a book I’ve been reading lately, entitled The Ancient Olympics, by Nigel Spivey. No, we are not going to be talking about modern warfare or guns, those are not my thing. However, Spivey’s use of the quote is apt for his book, and for the purposes of our short discussion here.

What was the purpose of athletic competition in the ancient world, and what is the purpose of it today? How has it evolved, or has it?

I’m just finishing up the research phase for my novel set during the ancient Olympics. I can’t wait to start typing away at it, but there are a few things I need to decide on, one of them being how I will portray the ancient games.

I’m a romantic, and an idealist, and at first my inclination is to portray the ancient Olympics in an idealized and romantic light. It would make for a great story, but would that be accurate?

Today, when we think of the Olympic Games, we think of amateur sport, sportsmanship and fair play. We believe that just to be able to compete in the Olympics is an honour, a victory already achieved. In some ways, that’s true. The athletes who go to the Olympics today have trained and competed for years. They’ve racked up a list of hard-won victories in their part of the world in order to make it to the Olympiad.

I love the Olympics. In fact, it’s the only time that I really watch sports on TV. I love the Olympic ideals we hold so dear.

But are those the same ideals that were held dear in the ancient world? Perhaps some. But not all. Are the Olympics today the same games that they were in the ancient world? No. Not really.

So, in writing my story set during the ancient Olympics, I’ve got to achieve a major shift in mindset and go somewhere my modern sensibilities will not necessarily enjoy.

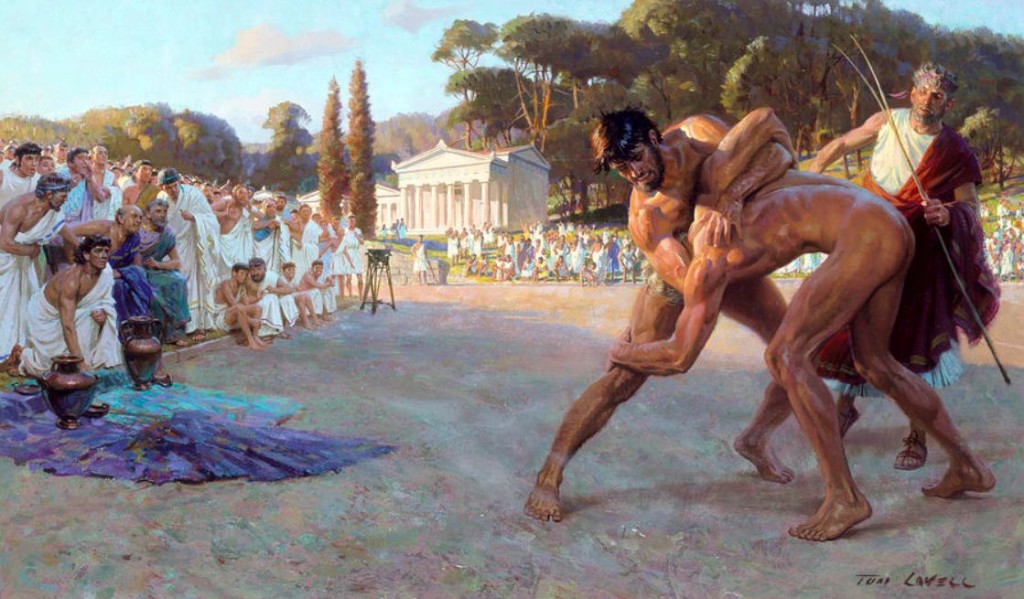

In the ancient world, men (yes, only men) went to the Olympics to win (women were only permitted to compete insofar as owning the horses in the equestrian events). It was not honourable to just participate. Oftentimes, losers would have to return to their polis by back streets, humiliated that they did not wear the olive crown of victory. Only the winners were hailed as demi-gods. The losers, though participants in the great games, were nothing.

It’s pretty harsh, but that was the nature of the Olympics and other games (including the Isthmian, Pythian, and Nemean games). They were violently competitive, brutal in nature, and though the Olympics were a time of official peace (the ‘Sacred Truce’), they were anything but peaceful.

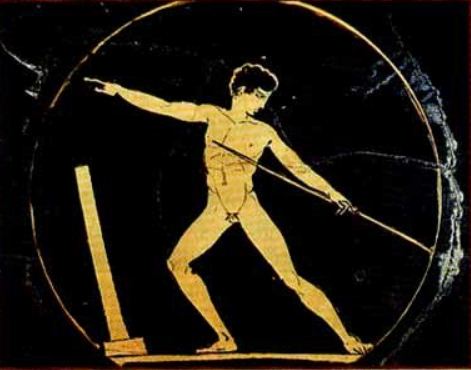

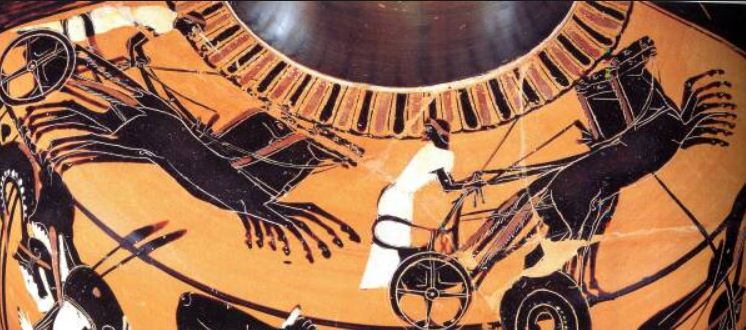

When I think of the ancient Olympics, I don’t think about gymnastics or synchronized swimming, kayaks, or graceful dives from on high. I think of boxing and the discus, hoplite warrior sprints and the roar of a crowd at the marquee chariot races. When I think of the ancient Olympics, I think of the pankration, that most brutal of events where bones were broken, and faces were smashed with fists covered in lead or leather.

So, were ancient sports just about a sadistic pleasure in violence, about merely bettering your competitors, about hatred being given a release? Was sport really war on a small scale?

There isn’t really a straight and easy answer to the question, I’m afraid. I suppose the answer is yes, and no. Certainly, when you look at the array of events, the games were in one form, a training ground for war, “war without the shooting”.

As today, there were probably ‘good’ and ‘bad’ men who competed. There were those whose sole purpose was to utterly humiliate and destroy their opponents, to inflict pain and suffering, but there were also men who, in competing in the sacred Olympiad, sought to honour not only their polis and their family, but also to honour the gods themselves.

That said, they all wanted to win. I suspect that athletes today, no matter how much the media proclaims their virtue for simply being there, today’s athletes, once there, can see that victory within their grasp, and so, crave it more than we realize.

There is a duality here that leads us to the nature of Strife in the ancient world, which Spivey touches on in his book.

The ancient poet Hesiod (circa 700 B.C.) spoke of Strife in his Work and Days.

So, after all, there was not one kind of Strife alone, but all over the earth there are two. As for the one, a man would praise her when he came to understand her; but the other is blameworthy: and they are wholly different in nature. For one fosters evil war and battle, being cruel: her no man loves; but perforce, through the will of the deathless gods, men pay harsh Strife her honour due. But the other is the elder daughter of dark Night, and the son of Cronos who sits above and dwells in the aether, set her in the roots of the earth: and she is far kinder to men. She stirs up even the shiftless to toil; for a man grows eager to work when he considers his neighbour, a rich man who hastens to plough and plant and put his house in good order; and neighbour vies with is neighbour as he hurries after wealth. This Strife is wholesome for men. And potter is angry with potter, and craftsman with craftsman, and beggar is jealous of beggar, and minstrel of minstrel. (Hesiod, Works and Days)

Here we see that ‘Strife’, who is named Eris, actually has two faces, or natures.

There is Strife as Eris agathos, the useful, productive aspect of Strife, that which lends itself to creative industry in all things, in people of all stations and trades.

Then there is the Strife known as kakochartos, or ‘exalting in bad things’. This aspect of Strife thrives on war and dissent, a lust for bloodshed and battle.

Both aspects of Strife were present in the ancient Olympics and other competitions, both were present in war.

In his Theogeny, Hesiod names three offspring of Strife. They are: Death, Destruction, and Toil (Ponos).

It is ‘Toil’ that the ancients ascribed goodness to, for in working to the extremes of ones capabilities, and beyond, one became stronger, and so achieved greatness. This sort of Strife, Eris agathos, was pleasing to the gods, it was something to aspire to.

But the two aspects of Strife are not, in my opinion, mutually exclusive.

Spivey mentions the Iliad, and the part of that wondrous foundational text of western literature where Achilles embodies both aspects of Strife. Homer does not differentiate.

Therefore, perish strife both from among gods and men, and anger, wherein even a righteous man will harden his heart- which rises up in the soul of a man like smoke, and the taste thereof is sweeter than drops of honey. Even so has Agamemnon angered me. And yet- so be it, for it is over; I will force my soul into subjection as I needs must; I will go; I will pursue Hector who has slain him whom I loved so dearly, and will then abide my doom when it may please Jove and the other gods to send it. (Home, Iliad 18)

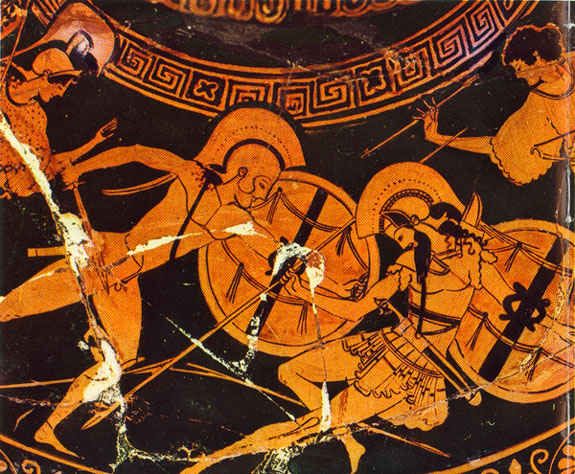

Achilles is by far the greatest hero of the Trojan War, the most skilled. He is godlike. He is what all men aspired to be. He is skilled at war, but can be unbelievably violent in the extreme, such as when he drags Hector’s body behind his chariot. He can, however, be moved to goodness such as when he sets aside his vendetta with Agamemnon to help his brothers again, and when he grants King Priam the return of his son’s body for the rites.

Greatness is not an easy thing to carry upon one’s shoulders, and we see in ancient literature that the heroes who achieve greatness also have a greater measure of grief. Herakles, Jason, Achilles and so many others all have tragedy in their lives, but Eris agathos was with them too, and this set them apart from the base war-mongers of the age, those who throve on kakochartos.

Olympians would have been weaned on tales of these heroes, and many would have aimed for such heights. One of the most famous of Olympians was Milo of Croton who won numerous wrestling victories at all of the Pan-Hellenic competitions for many years.

This same Olympic hero was also a great warrior who led troops of his native Croton in battle against their enemies of Sybaris.

One hundred thousand men of Croton were stationed with three hundred thousand Sybarite troops ranged against them. Milo the athlete led them and through his tremendous physical strength first turned the troops lined up against him. (Diodorus Siculus XII, 9)

It is said that Milo led the charge against the Sybarites wearing his Olympic crowns, a lion skin, and wielding a club similar to the hero Herakles. It seems that war and athletics were both at their finest in Milo, and I suspect that it was so in many an ancient Olympic champion.

Herakles wearing a victor’s wreath – This is how Milo supposedly dressed for the battle with Croton’s enemies