Salvete Readers and Romanophiles!

If you missed the first post on drama and actors in ancient Rome, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In part two of this series, we’re going to be looking at the evolution of the structure of the theatre during the Roman period, the places where actors performed, from the dirtiest street corner to the most magnificent structures of the Empire.

We hope you enjoy!

The ancient theatre of Epidaurus

One of the main questions I had when I set out on the research for this latest book was around the physical structure of the Roman theatre. Of course, I knew about ancient Greek theatres, having visited several in my travels over the years. But what about Roman theatres? Did the Romans simply re-use Greek odea? Did the Romans build their own theatres and, if so, how did they differ from those built by the Greeks?

In this blog post, we’re going to be taking a brief look at theatres in ancient Rome and how they differed structurally from those of the Greeks.

The ancient Greeks were, of course, the progenitors of drama and the theatre. When one thinks of ancient theatre, it’s difficult not to think first of an ancient Greek theatre such as the the magnificent, and still-used, example at ancient Epidaurus in the Peloponnese. Or even the beautiful, silent ruins of the great theatre of Argos. It is quite an experience to sit in the ancient seats and not feel some sort of communal awe from centuries past, looking out to the distant mountains or sea beyond the stage where ancient actors would have enacted stories of gods, goddesses, heroes, and the trials and tribulations of everyday people on their journey through this life.

The ancient Greek playwrights – Euripides, Sophocles, Aeschylus, Aristophanes and others – had a way delving deep into the heart of human emotion and experience and making people linger there so that they would, hopefully, come out of it a bit more enlightened. And in a setting such as those ancient theatres, it would be hard not to.

I’ve seen comedic and tragic plays performed while sitting with thousands of others beneath the stars in an ancient theatre. It is an experience I shall never forget.

But even if one is not moved by the words spoken by the actors, it is difficult not to marvel at the genius of the architecture that allows the audience at the top of the seats to hear a whispered word spoken from the centre of the orchestra.

Ancient theatres really are engineering wonders!

The ancient theatre of Argos, Peloponnese, Greece.

Of course, the men of the Tiber knew a good thing when they saw it, and so they eventually adopted drama and theatres while adding their own Roman flair.

But this took some time, and some convincing…

Drama and theatre first came to Rome through contact with the Greek cities to the south and the Etruscans to the north, who had regular contact with the Greeks. It might have been looked upon with suspicion by conservative Romans at first, but eventually, drama would take hold of the Roman people.

Etruscan Entertainers

In 364 B.C., the Roman Republic was hit by a plague, and in an effort to please the gods and entreat their aid, Rome vowed to hold theatrical festivals in their honour.

To do this, Etruscan actors were brought in and the rest is history. This considered by some to be the start of this new entertainment for the Roman public, an entertainment inspired by the Greek cities of southern Italy.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens

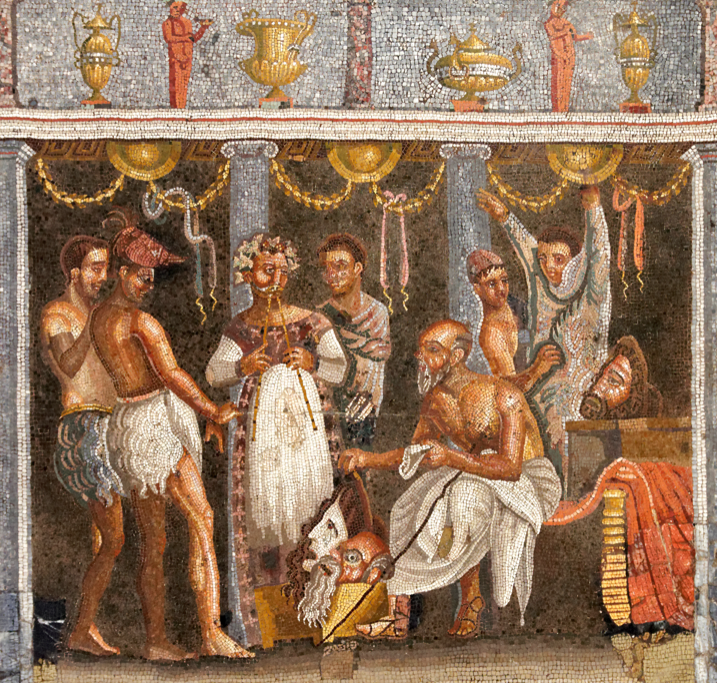

Plays were originally performed in Greek, but over time Latin playwrights emerged, such as Plautus, Terence, and others. Of course, there were tragedies and comedies in the beginning, but then folk and bawdy plays began to take hold, and the mimes and pantomimes became the most popular among ancient Romans.

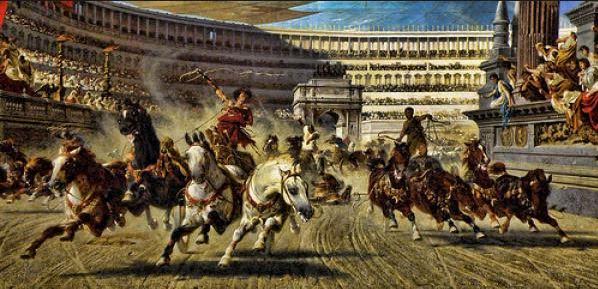

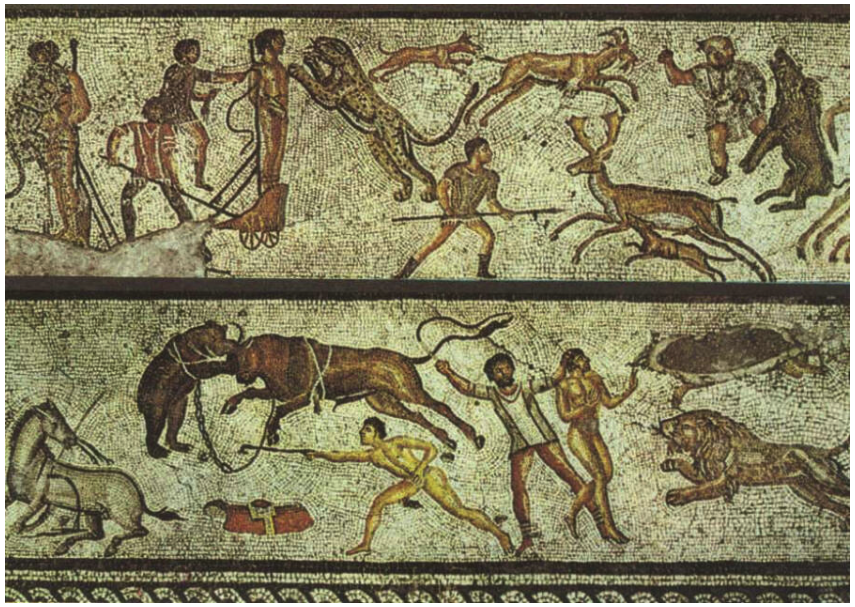

To read more about the types of literature in ancient Rome, including drama, CLICK HERE. Suffice it to say that theatrical performances eventually became nearly as popular as chariot racing and gladiatorial combat in ancient Rome.

Temple of Antoninus and Faustina, Roman Forum. Play were sometimes performed on temple steps such as this.

There may have been theatres dotted all over territories which Rome had conquered early on, but in the city of Rome itself, there were no stone theatres at first, not like in Greek cities where a theatre was a given sign of civilization.

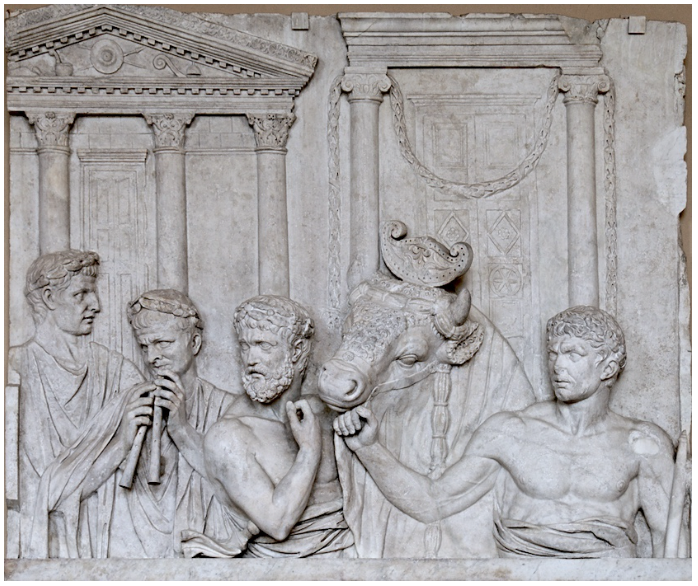

Early dramatic performances in ancient Rome were either performed on the steps of temples or on temporary wooden stages which were constructed in the Circus Maximus or Roman Forum for festivals. After the performances were finished, they were torn down.

Despite the popular appeal of drama in ancient Rome, conservative elements had a deep dislike of the theatre, viewing it as ‘too Greek’ and opposed to Roman values. The theatre – especially the mimes and pantomimes – were viewed as lewd, and this is a view that continued into the Christian era.

But, even among conservative Romans, it was hard to fight popular appeal, and the theatre was indeed growing in popularity.

Roman Re-enactors on the steps of a temple in Spain (photo: Turismo de Merida)

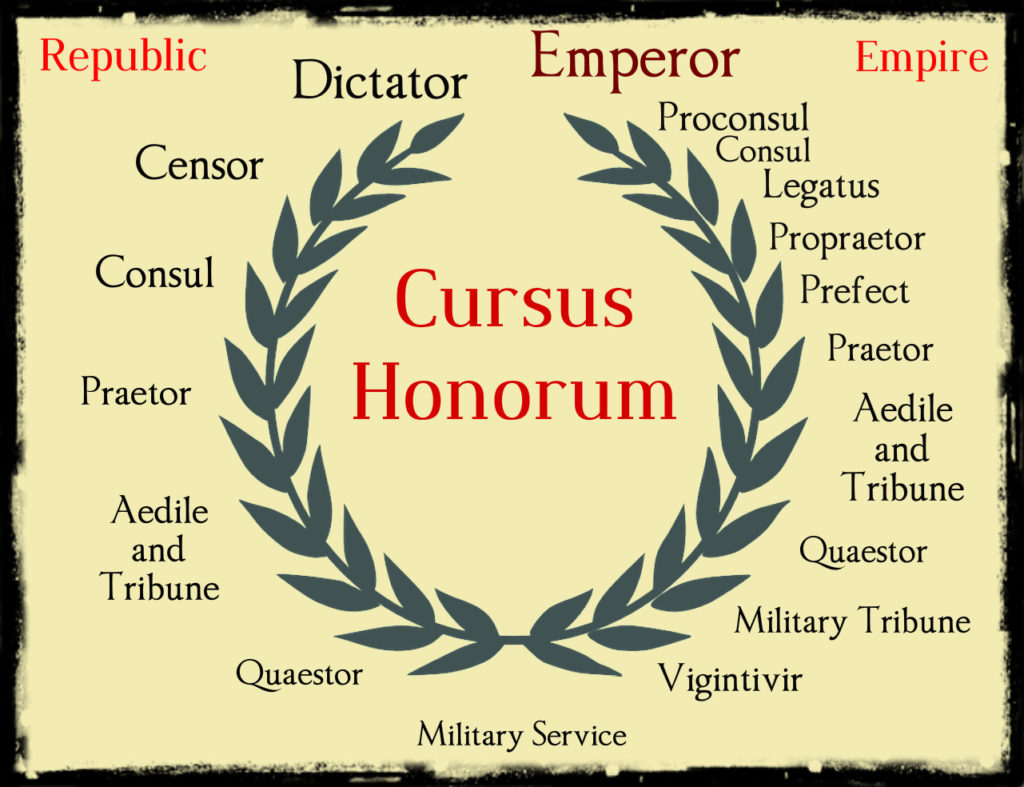

As we know, the Romans loved their games, or ludi, and by sponsoring these games, Roman magistrates had found a way to win the political favour – and hence, votes! – of the people.

Some examples of games which featured theatrical performances were the Ludi Apollinaris in honour of Apollo (July 6-13) and the Ludi Megalenses in honour of Cybele (April 4-10).

The building of theatres became a way to win the favour of the people. Unlike today when, sadly, theatre is viewed as something more for the elite or well-to-do, the theatre was, in ancient Rome, for people of all classes!

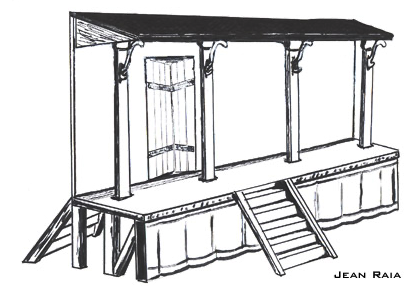

As mentioned, at first theatres in Rome were temporary and constructed of wood, but as time went on, even these wooden ones became more elaborate.

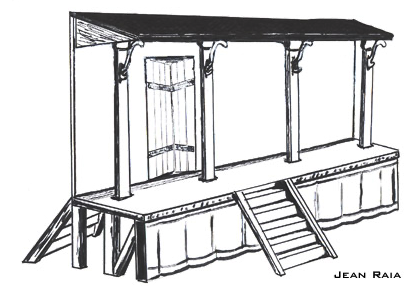

Artist Impression of temporary wooden stage of Roman period (image: Jean Raia)

In 58 B.C. Marcus Aemilius Scaurus built a wooden stage for performances, but this one had columns of African marble, as well as statues, glass, gold and fabrics to adorn it. The people loved it!

In 52/51 B.C. Gaius Scribonius Curio even built two moveable semi-circular theatres that could be pushed together to build an amphitheatre so that plays could be performed during the day and gladiatorial games viewed at night!

Eventually the time would come when Rome would receive its first stone theatre, despite conservative opposition, and this was given to the people by none other than Pompey the Great.

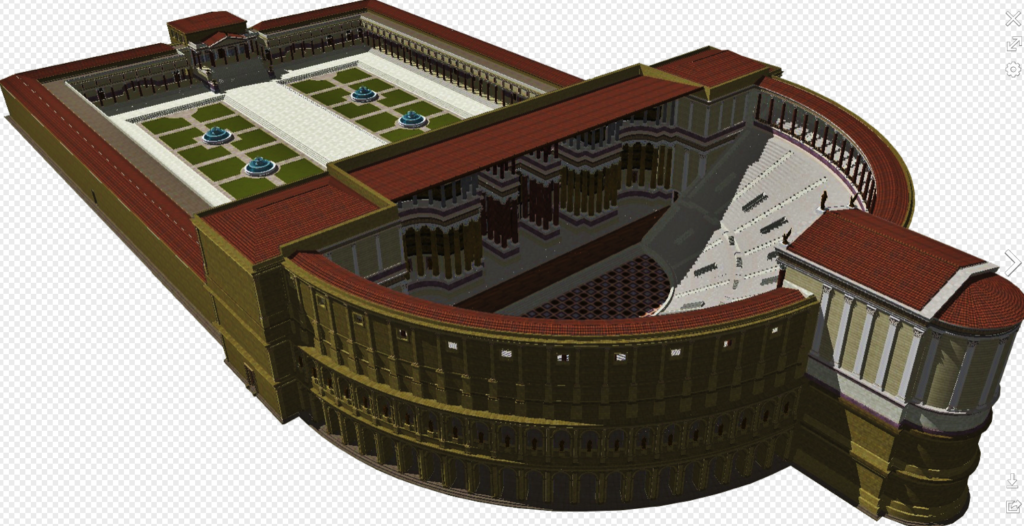

Reconstruction of the Theatre of Pompey in Rome with attached gardens and temple above the theatre seating. More on this magnificent setting in a later post!

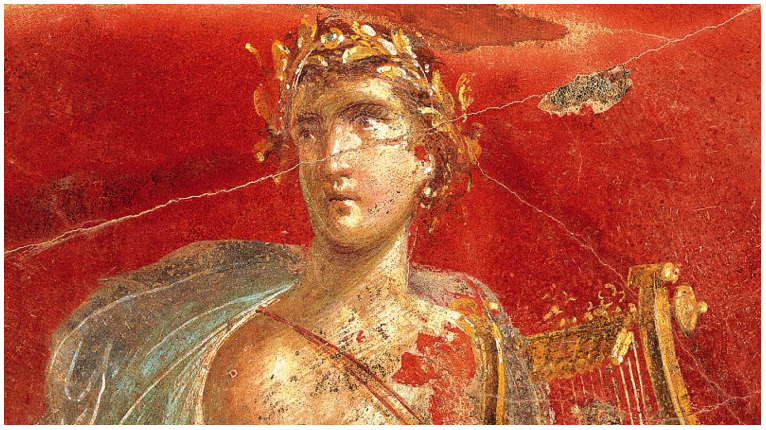

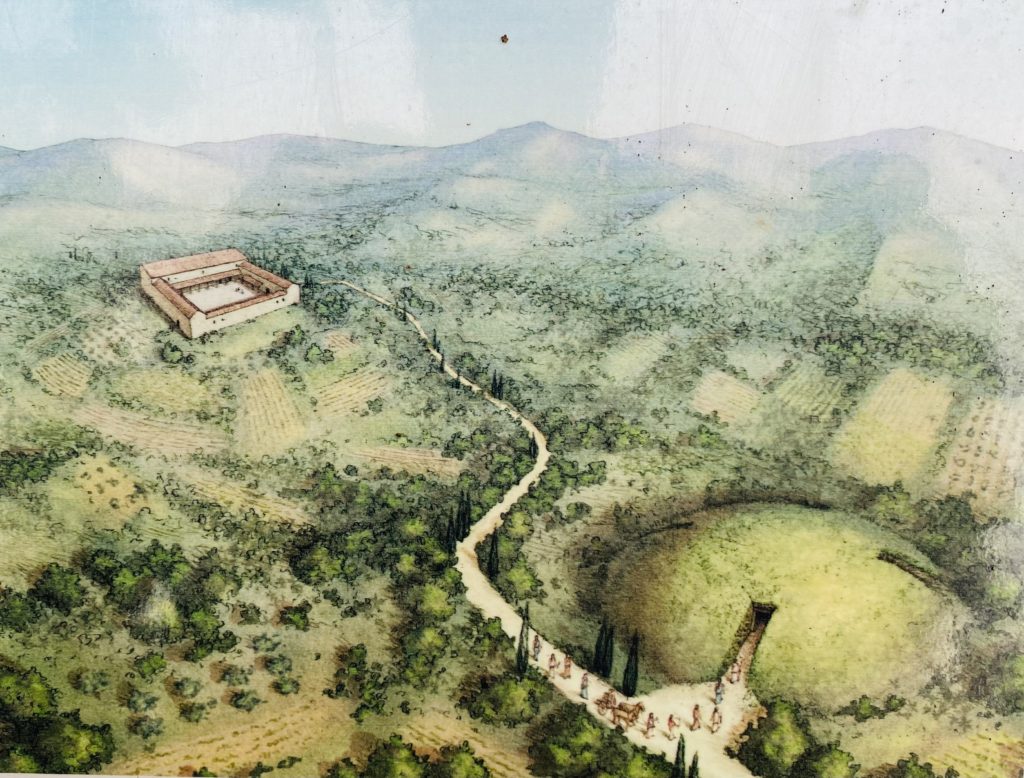

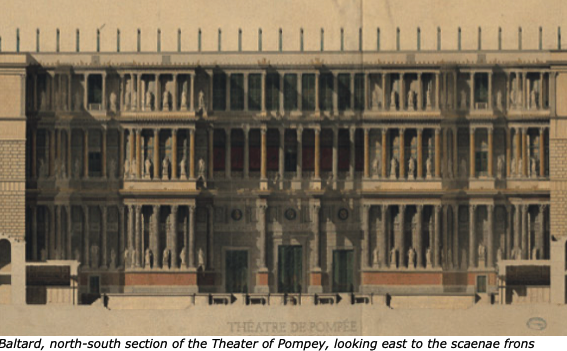

From 61-55 B.C., Pompey built a magnificent stone theatre for Rome, and he appears to have used his general’s wiles to get it done in a way that tricked conservative dictates. You see, this was not only a theatre, but also a temple complex dedicated to the goddess Venus herself.

Atop the great theatre of Pompey, resting above and behind the seats of the auditorium, was a magnificent temple of Venus. The argument was, it seems, that the theatre itself was simply the substructure of the temple, the ‘real’ purpose of the construction. The gods were now present in the theatre, and no one would have dared to tear it down!

The theatre of Pompey is now, perhaps sadly, known as the place where Julius Caesar was murdered (the senate was meeting there at the time), but more importantly, it was the beginning of a greater acceptance of theatre in the city of Rome.

Indeed, after the accession of Augustus, one of his supporters, one Lucius Cornelius Balbus, built a second stone theatre in Rome, on the Campus Martius, known today as the Theatre of Balbus.

Model of the Theatre of Balbus

These permanent Roman theatres, however, were more than places to stage dramatic performances. They were also meeting places that incorporated religious elements. There were temples, and gardens and courtyards where people could stroll between acts, or meet outside of performances. They became part of the fabric of the city of ancient Rome.

But what were the structural differences between ancient Greek and Roman theatres?

It is impossible to deny the simple beauty of ancient Greek theatres, and the brilliance of their acoustic design. It is truly astounding to sit at the top of the seats and hear someone drop a coin or light a match in the middle of the orchestra!

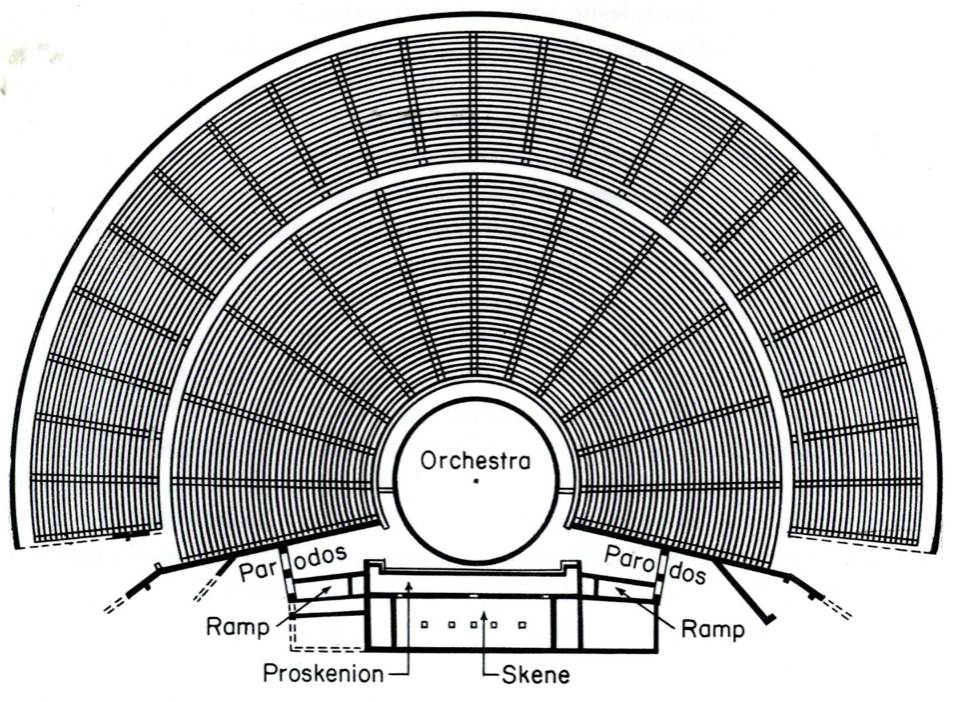

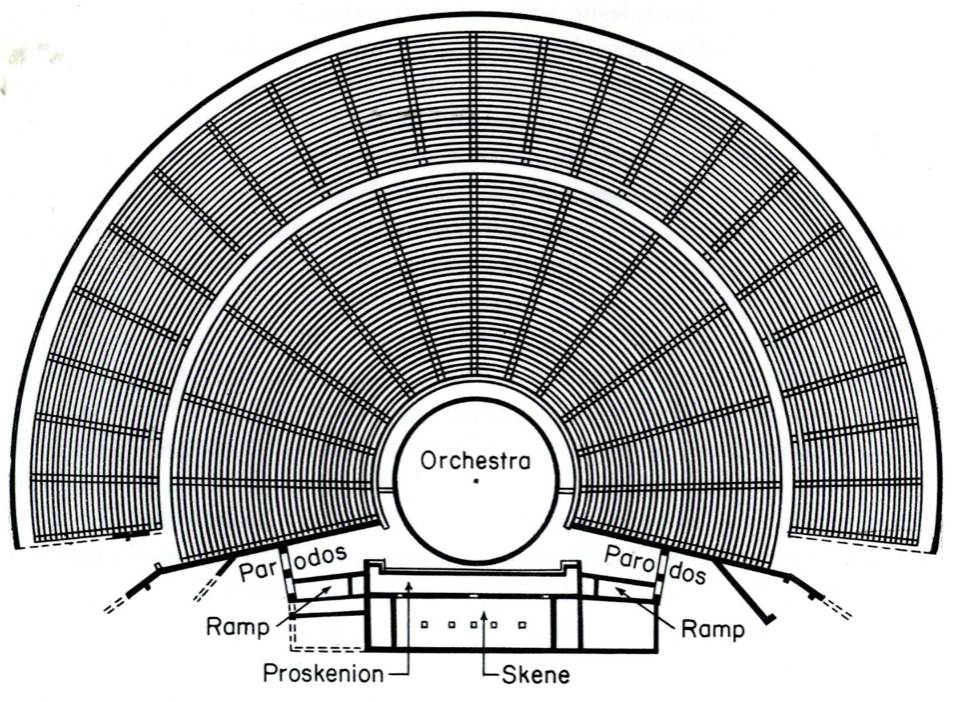

Plan of an Ancient Greek Theatre

Roman theatres were of course, based on Greek designs. Even the Romans could not deny the acoustic uses!

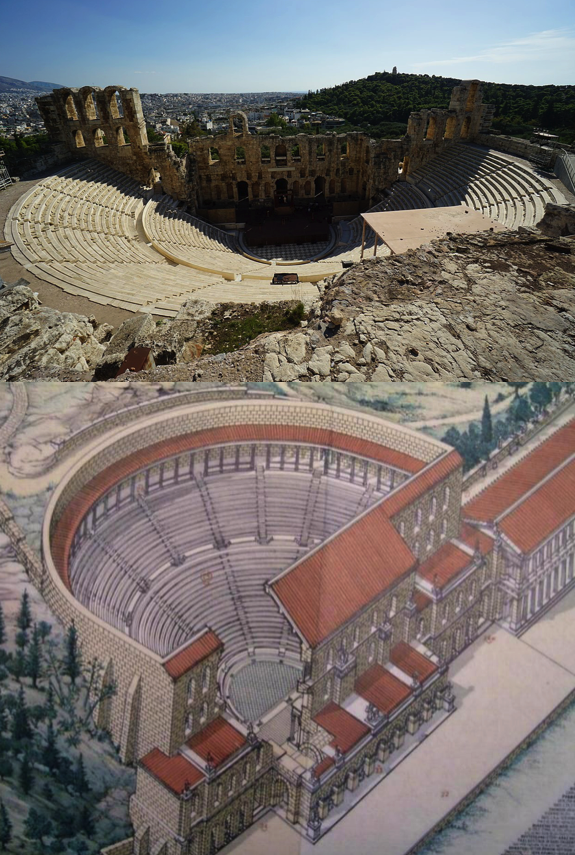

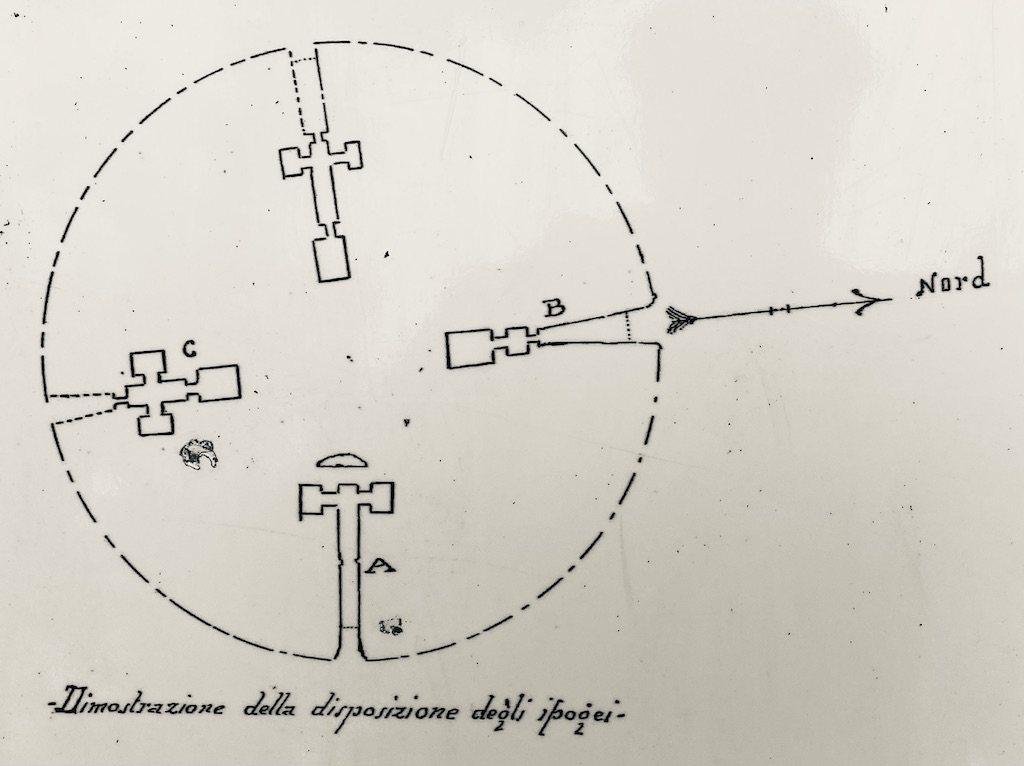

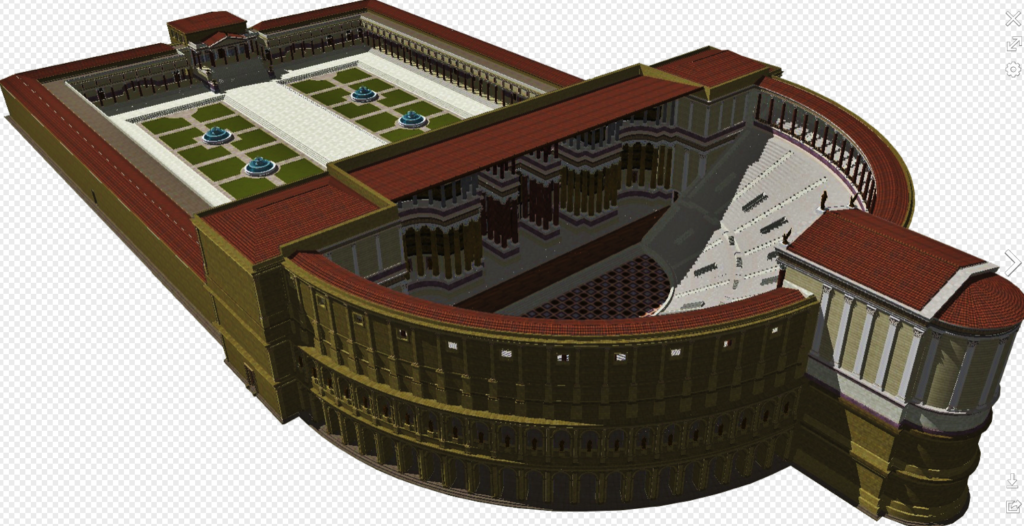

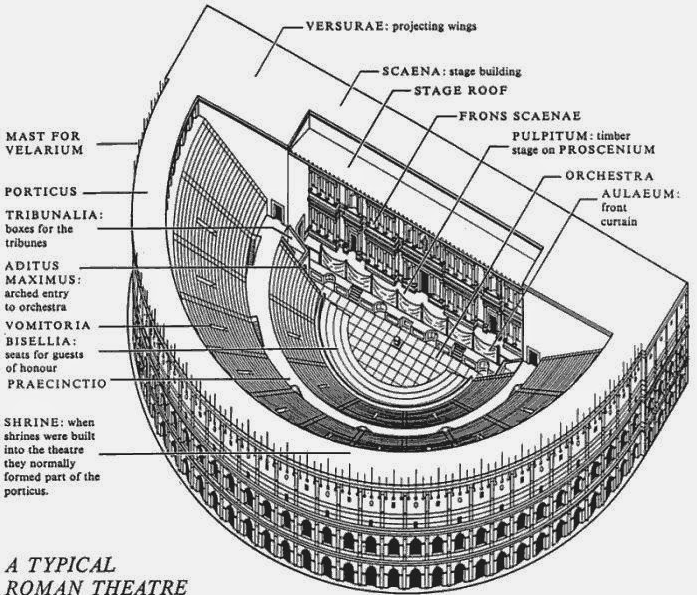

But whereas Greek theatres, or odea, were normally built into a hillside and had round orchestras where the performance took place, Roman theatres were more often stand-alone structures with semi-circular orchestras where seating was reserved for high-ranking officials, senators, or members of the imperial family. Roman theatres were constructed with solid masonry or vaults that supported the curved or sloping auditorium seats, or cavea. This design sometimes included a colonnaded gallery around the outside that gave easier access to the tiers of seats.

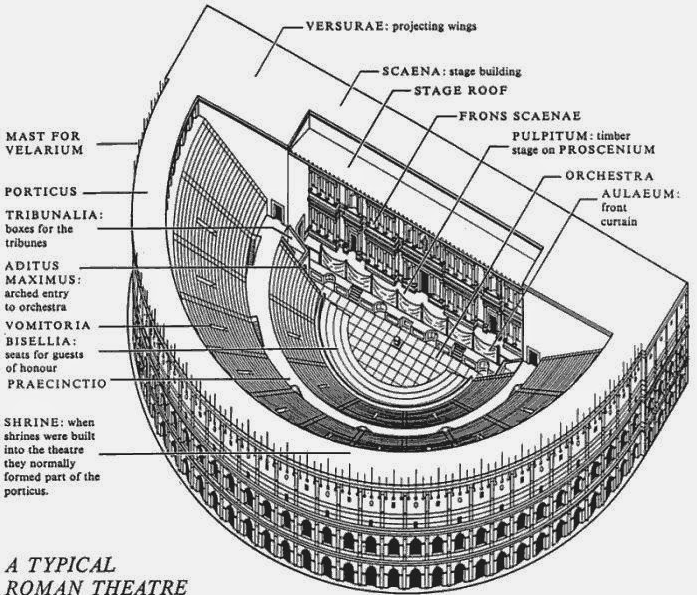

Plan of a Typical Roman Theatre

Another innovation given to the theatre by the Romans was the inclusion of a curtain before the stage. Today, it is hard not to think of a curtain in a theatre, and we owe this to the Romans. The difference was that where today the curtain hangs from above, in a Roman theatre, the curtain, or aulaeum as it was known, retracted into a pit in the floor before the stage at the beginning of the performance, and rose out of it at the end.

The most noticeable difference between Greek and Roman theatres, however, was the Roman scaena.

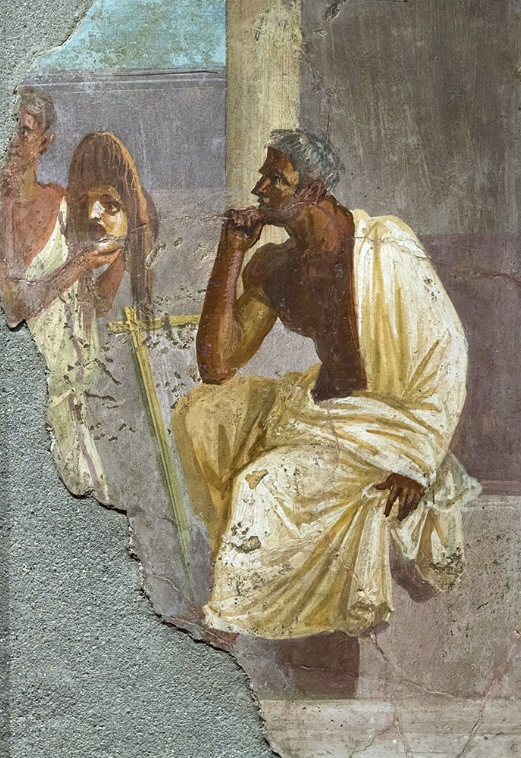

In an ancient Greek theatre, initially, the chorus and actors performed on the round orchestra, but later on, a raised stage, or proskenion, was incorporated. At the back of this stage, they began to build a one or two-story backdrop known as a skene, the ‘scene’ before which the action took place, and behind which the actors could change. The Greek skene did not obstruct the view beyond the theatre, however, but rather just provided the ornate backdrop.

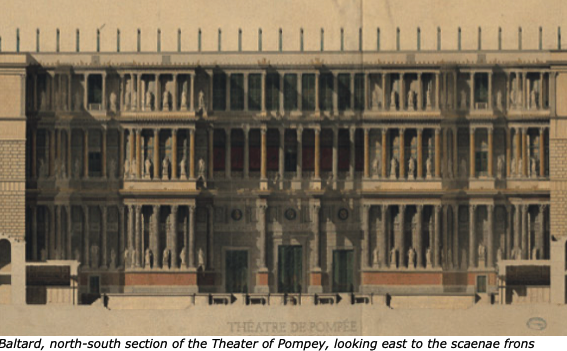

The scaena frons of the Theatre of Pompey

The Roman scaena, however, was much more substantial, for it more or less enclosed theatre completely and provided a full divider between the audience and backstage.

Scaenae frons in Roman theatres had three or five doors flanked by columns and statues in niches. The scaena and its doors could provide the setting for a street scene, houses, palaces etc., and sometimes it was even sectioned off with smaller curtains called siparia as needed.

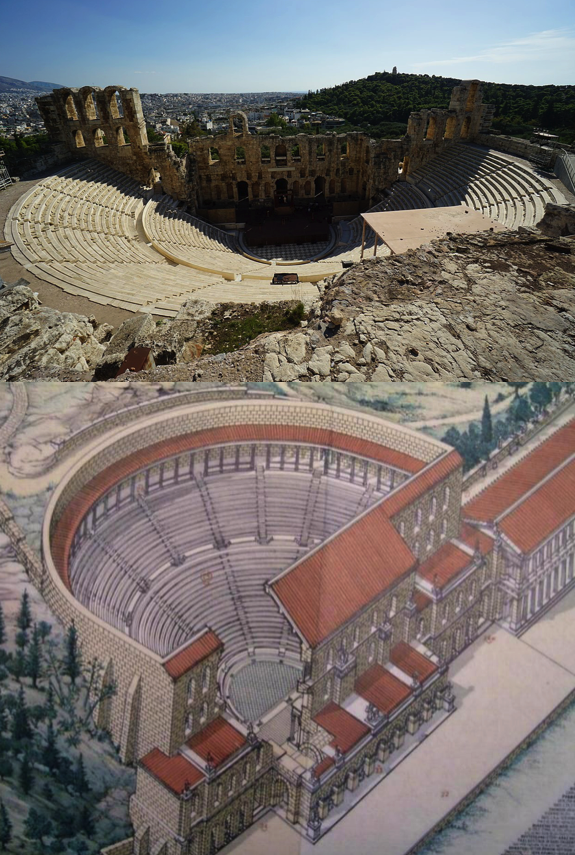

The Roman-era theatre of Herodes Atticus, Athens

The Roman scaena also rose to the full height of the theatre itself, either level with the rear seats of the auditorium, or even higher. There was also a wooden roof above the stage of Roman theatres that also acted as a sounding board.

It wasn’t just the actors who were protected from above either, for in some Roman theatres there could also be an awning above the auditorium known as a velarium, to shield the viewers from sun and rain. Roman theatres also had covered porticoes where audience members could go between performances.

The Romans did like their comfort!

The Roman theatre in Thugga, Tunisia, featured in Killing the Hydra (Eagles and Dragons Book II)

Were Roman theatres built across the Empire once Rome had made its own innovations in theatrical architecture?

Well, it seems the Romans did make adjustments to some Greek theatres by adding their own scaenae. However, especially in the Hellenistic east, Greek odea continued to be used, only just for more refined performances of music and poetry recitations rather than for populist mimes and pantomimes.

Romans continued to use the odeon design when called for, but sometimes with the addition of a roof. This type of smaller, enclosed and roofed theatre was known as a theatrum tectum. An example of this is the one built in Pompeii in 79 B.C.

Aerial view of theatres of Pompeii. Note the theatrum tectum on bottom right which would have been fully enclosed.

When it comes to theatres and theatrical performance, whatever the genre, the Greeks and Romans did have this in common: theatre was extremely popular with the people and important for the social life of the community, be it in the cultured metropolises of the Empire, or on the distant borders, far from the beating heart of Rome.

The Greeks may have invented theatres, but some might argue that it was the Romans who perfected them.

Thank you for reading.

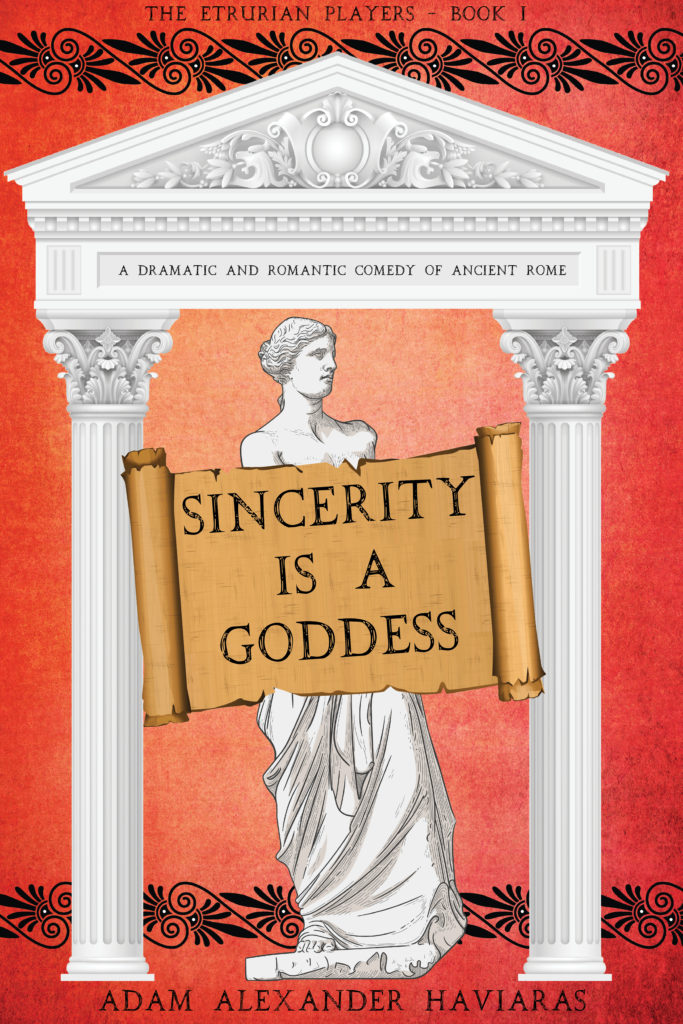

Sincerity is a Goddess is now available in ebook, paperback and hardcover from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortal chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy and get ISBN#s information for the edition of your choice.

The Etrurian Players are coming! Brace yourselves!