Greetings History-Lovers!

This week on Writing the Past, we have a special post to share with you.

This past summer, after twenty-two years, we were finally able to make a return trip to the Greek island of Santorini to visit the archaeological site of ancient Akrotiri.

It was a magical journey to a place that has not changed in thousands of years, on an island that has, in a way, changed a great deal.

Today, we want to share a bit of our adventure with you…

Santorini from Space (photo: Nasa Earth Observatory)

It is no secret that we visit Greece often. It is our other home and the place where most of our family is located. While we have our usual haunts, we do try to visit different places and islands whenever we are there.

This year, our family voted to go back to the Cyclades, that magical, swirl of rocky islands almost smack dab in the middle of the Aegean Sea. When one thinks of the Cyclades, one thinks of rocky shores dotted with whitewashed buildings with blue trim, brilliantly-clear turquoise beaches, and sunsets so beautiful they burn into your memory forever.

This group of islands set in the midst of Homer’s eternal wine-dark sea, is a place of gods and goddesses, of myth, and of legend.

When one thinks of the Cyclades, or the Greek Islands in general, it is no great surprise that the island that most often comes to mind is Santorini, and that is the island our family decided on.

When we began planning our Aegean odyssey last winter, it quickly became apparent that things had changed in the last twenty-plus years since we had last been there, mainly the prices.

The first step was to book our ferry tickets out of the ancient port of Piraeus, and herein was our first surprise. Whereas twenty years ago one could get ferry tickets to Santorini for around $40.00, we were shocked to see that the average cost now was closer to $200.00 per person!

After searching for some time, we found a better price and jumped on the tickets quickly as the ships were already selling out out. (CLICK HERE to see how we found the best deal).

Tickets in hand (plane and ferry), all that was left was to wait until summer. It was a long wait, but eventually, the time came for us to board.

Boarding Minoan Lines’ ‘Santorini Palace’ ship

When we arrived in Athena’s beautiful polis, it was in the midst of a heatwave in which temperatures hovered around 45 degrees Celsius! Let us just say that, in Athens, without air conditioning, that is hotter than Hades!

After four scorching days, it was time to board our Minoan Lines ferry at Piraeus, which we did after a tense taxi ride in which the driver seemed to be battling an army of tourists doing the exact same thing. It was as if the heat was driving everyone out of the city into the Aegean’s embrace.

Eventually, perspiring in the extreme from the outset, we found our ship, lugged our suitcases into the hold, found our seats, and settled in for the eight hour trip to our destination.

There is something special about sailing on the Aegean, a feeling one gets that is difficult to explain, but is inevitably brought about by that vast blue expanse.

Perhaps it is the fact that the Odyssey is so ingrained in our western psyche that there is an immediate sense of adventure, or even of impending danger around the next ‘corner’ of the journey? Or maybe it’s just the gentle lulling one experiences when immersed in myriad shades of blue beneath an Aegean sun.

Whatever it is that weaves a spell, as we reclined in our seats, the ship riding the waves like Poseidon’s hippocampus, we thought on the things we wanted to do during our three day sojourn on Santorini. Of course, eating as the sun set, swimming, and a bit of shopping were on the list, but top of mind for the history-lovers among us was our visit to the archaeological site of ancient Akrotiri.

Minoan Boxers and the Saffron Gatherer, from Akrotiri

For those of you who may not be familiar with the history of Santorini (or ancient ‘Thera’ or ‘Calliste’ as it was called in the ancient world), the island was part of the Minoan civilization that was based on the island of Crete. Minoan civilization is often considered the earliest in Europe, and the Minoans themselves were highly advanced and traded all over the Mediterranean. They excelled in in art and architecture, though they also manufactured weapons.

This beautiful civilization, whose influence was felt across the Mediterranean world, existed from about 3100 B.C. to roughly 1100 B.C. when they were finally overrun but the much more warlike Mycenaeans. It was in the midst of this long period of existence that Minoan civilization experienced one of the most devastating natural disasters in human history – the Minoan Eruption at Thera.

Santorini’s Port and the Caldera

The eruption of the volcano of ancient Thera, which occurred sometime between 1600 and 1500 B.C., was catastrophic and is thought to have been one of the largest volcanic events to have ever occurred on Earth. It completely destroyed the island of Thera and the Minoan settlement of Akrotiri which was buried under layer upon layer of rock and ash. As a result of this cataclysmic eruption there were earthquakes, tsunamis, and mega-tsunamis that even destroyed parts of Minoan civilization on Crete far to the south.

The island of Thera, which was once whole, was blown to bits giving it the now-familiar crescent shaped outline we know today with the still-active volcano sleeping menacingly in the middle of the caldera.

The Minoan settlement of Akrotiri had been silenced forever after that eruption.

It is said that Akrotiri is the ‘Pompeii’ of Greece, but in reality the eruption was much worse. It is believed that the Minoan eruption at Thera was one-hundred times more powerful that the eruption of Vesuvius which destroyed Pompeii.

This ancient island of dangerous beauty was our destination as our ferry cut its way across the Aegean from the mainland, and while my mind wandered back in time to my previous visits to the island, our ship stopped at other islands en route.

Syros, Mykonos, Paros, and Naxos all teased us with their cliffs and beaches, their rocky shores surrounded by winking waves, all of them beautiful, and unique, and tempting. It is one of the joys of travelling by ship on the Aegean that one gets to see other islands along the way to your destination.

However, as Santorini came into view through the heat and sea haze, we were quickly reminded of how different it truly is from other islands.

Santorini’s Cliffs

Even approaching on a decent-sized ship, one feels small sailing up to Santorini with its red, black, and tan cliffs towering over you, topped by the whitewashed towns of Fira and Oia. You want to immediately disembark, to get to the top of the island and peer out over the world, but there is one thing that draws the attention away as you approach: the volcano.

Like a black, sleeping Titan in the midst of the deep caldera, you are acutely aware of the dark force that destroyed Akrotiri and the Minoan settlements on Thera. You are ever aware – once you find out – that the volcano is still alive.

That is something that rests at the back of your mind during your stay on this mysterious island.

Cruise ships around the volcano

As we said before, while some things on this ancient island have remained the same for thousands of years, other things on Santorini have changed a great deal. For us, this was quite evident in the costs of, well, everything!

Santorini is not an island for budget travellers, and it took some searching to find a hotel that did not cost more than the Golden Fleece. Thankfully, we succeeded in finding a welcoming roof that was centrally-located at the Nautilus Dome Hotel (CLICK HERE for a full review of this lovely hotel).

After the shock of disembarking into the chaos of Santorini’s port, we found our shuttle to the hotel and quickly got out, the car taking the long, switchback road up the cliff face to the summit.

The Nautilus Dome welcomed us with beautiful surroundings accented with bougainvillea and palms rustled by the hot Aegean breeze and views of the sea and caldera on two sides, the hilltop village of Megalochori on another, and Fira where it lay baking in the cliff-top sun on the other.

Entrance to the Nautilus Dome Hotel

After settling into our accommodation, it was time to head into Fira town for an evening of food, wine, and browsing the shops. The next morning we were scheduled to visit the archaeological site, and we went to sleep beneath a star-pocked sky, thinking of walking the long-silent streets of Akrotiri.

When morning came, it was bright and breezy, and the heat settled on that rocky landscape early in the day. We had a hearty breakfast, gathered our gear, and set out for Akrotiri.

Santorini Sunrise

When visiting Santorini, some people chose to rent a car or scooter or ATV, but we have always found that the buses are very reliable, and that they get you everywhere you want to go, including the archaeological site. The fare is only about two Euros per adult, so it is also affordable.

While riding the bus through various villages, one also notices how desolate the landscape is. This island is volcanic and very little grows here other than the famous grape vines used to make Santorini’s Assyrtiko wine, something that has been done for over 3,500 years.

One notices these strange, low vines that look more like bushes everywhere one goes on the island. They fill every field and backyard and, though they are ever-present, the yield is quite low, a major factor, we were told, in the high cost of Santorini wines.

When we arrived at the bus stop outside the ticket office for Akrotiri, our eyes were met with a blinding light and radiating heat that both seemed to be amplified by the rocky landscape where natural shade is a rarity.

Entrance to the archaeological site of Akrotiri

Fortunately for us, and perhaps unfortunately in a way, there were not many tourists heading to the archaeological site, most people opting to head from the bus stop to the nearby ‘Red Beach’ for the day.

Our footsteps, however, led us up the path to the archaeological site which is, thank the gods, covered and enclosed.

As we stepped from the blaze of Helios’ chariot outside into the dark silence of Akrotiri’s remains, a silence fell that is somewhat inexplicable.

Akrotiri is an ancient ghost town.

Main street of archaeological site

To visit ancient Akrotiri today is to be touched by a deep sadness. You ask yourself What happened here? though you well know the answer. You feel an affinity for the people who lived here, who shopped along those silent streets, who raised families, who ran their businesses or traded with others from across the sea.

As we walked around the perimeter of the excavations, peering down into the houses, buildings, and streets, admiring the remains of beautifully-decorated amphorae from the modern walkways, our imaginations could not help but hear the screams of the Minoans there, of men, women, and children who realized their world was coming to an end.

The sleeping Titan among them was awakening.

Minoan ship procession from Akrotiri

Unlike Pompeii however, the population of which Vesuvius destroyed so violently, so absolutely, no human remains have been found at ancient Akrotiri. Not a single body buried beneath the layers of rock and ash.

Akrotiri is a tomb without remains.

As one walks around the deserted settlement, it is something of a comfort to know that the Minoans of Akrotiri seemed to have had enough warning to be able to perform an orderly evacuation of the island before the eruption.

Whether their great sailing ships escaped the subsequent tsunamis, we do not know. Perhaps the people of Akrotiri went to the bottom of Poseidon’s sea, or perhaps they escaped to Crete, or to other friendly shores. No one knows for certain. It is one of those ancient mysteries we will never really know the answer to.

Storage amphorae at Akrotiri

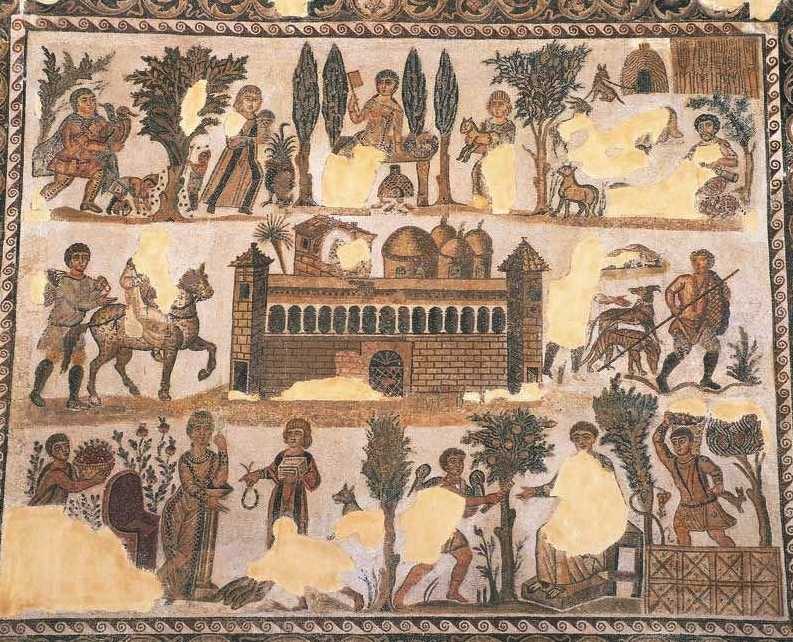

Walking around the archaeological site, after one comes to terms with the tragedy and magnitude of what happened to the island, to the settlement of Akrotiri, you then begin to notice the details of the settlement.

Akrotiri was indeed an advanced civilization. From the walkways we could see two and three-storey buildings and homes. There are the remains of toilets, and drainage systems, and sewers. There was ventilation in homes to allow for cooling during the Mediterranean summer. They had ways of keeping their food properly stored so as to preserve it.

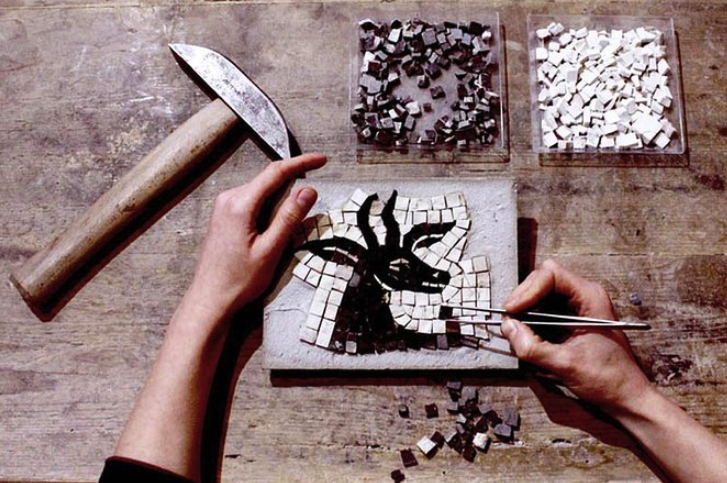

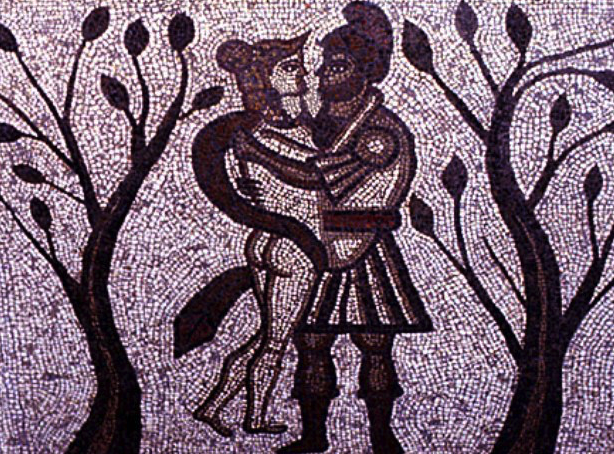

And there was art, oh yes…

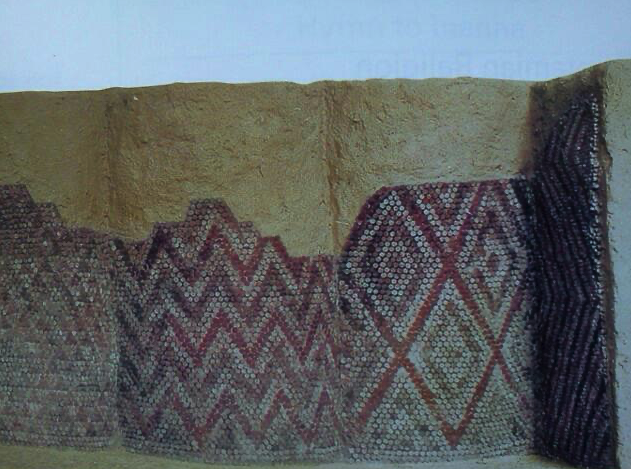

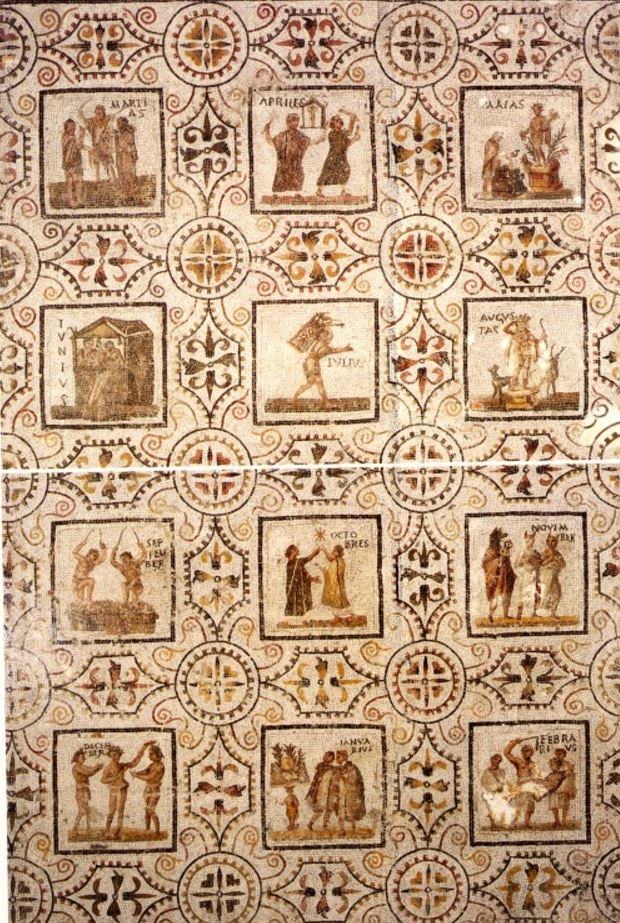

The ‘Spring Fresco’ from Akrotiri (National Archaeological Museum)

Perhaps some of the most beautiful pieces of art from the ancient world are from Minoan civilization, and from Akrotiri itself. The homes of the people of Akrotiri were richly decorated with frescoes exploding in colour, displaying plant and wildlife, the people, and their seafaring world. Many of these frescoes are on display in the new museum in the main town of Fira, and at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

Whether Akrotiri was the doomed civilization of ‘Atlantis’ mentioned by Plato, as some scholars have supposed, we cannot say for certain (another ancient mystery!).

What we can say for certain, however, is that the Minoan settlement of Akrotiri was part of a beautiful, advanced civilization that met a sudden and terrible end.

As we finished our walk around the archaeological site, imagining what life might have been like there, mesmerized by the beauty of a Minoan house as recreated in a short video beside that very house, a strange feeling came over us. It was something that cannot really be explained.

That silence returned, a deep and eerie silence. The hum of tourist voices and fans seemed to turn to wind blowing through the main street of Akrotiri, pushing dust through thresholds and off of windowsills where people once peered down to the street below.

Though nobody seems to have perished at Akrotiri during the eruption of Thera, it still feels like a place of ghosts.

Minoan people lived here, they loved, they laughed, they worked, they created works of art, and when life happens in a place, that leaves an imprint on that place, and on time itself.

Ancient Akrotiri is indeed a place of ghosts, but also a place of vibrant life.

We were reminded of that on our return journey there.

As we stepped back out into the bright light of day, Helios’ chariot now high in the far-blue Aegean sky, we wondered what the great Minoan eruption of Thera must have felt like for the people of Akrotiri. Certainly the gods must have been angry with them for, as history teaches us, no civilization is without fault or hubris.

Then we remembered that the Titan that destroyed the island was yet sleeping in the caldera of Santorini very near to us, and we pushed the thought away, not wanting to wake it.

Hot and overwhelmed by what we had seen, we joined the long train of people making their way to the nearby ‘Red Beach’. It was time to cool off in the sea beneath rich red volcanic cliffs, to rest and reflect in that desolate landscape now packed with masses of spendthrift tourists.

The world of the Minoans of Akrotiri, their homes, their art and artifacts, and their end still haunt us.

We may never return to Santorini, that ancient island of Thera, but we will be thinking of Akrotiri’s silent, ancient streets for years to come…

Thank you for reading.

Santorini Sunset