If ever a man strives

With all his soul’s endeavour, sparing himself

Neither expense nor labour to attain

True excellence, then must we give to those

Who have achieved the goal, a proud tribute

Of lordly praise, and shun

All thoughts of envious jealousy.

To a poet’s mind the gift is slight, to speak

A kind word for unnumbered toils, and build

For all to share a monument of beauty.

(Pindar; Isthmian I, antistrophe 3)

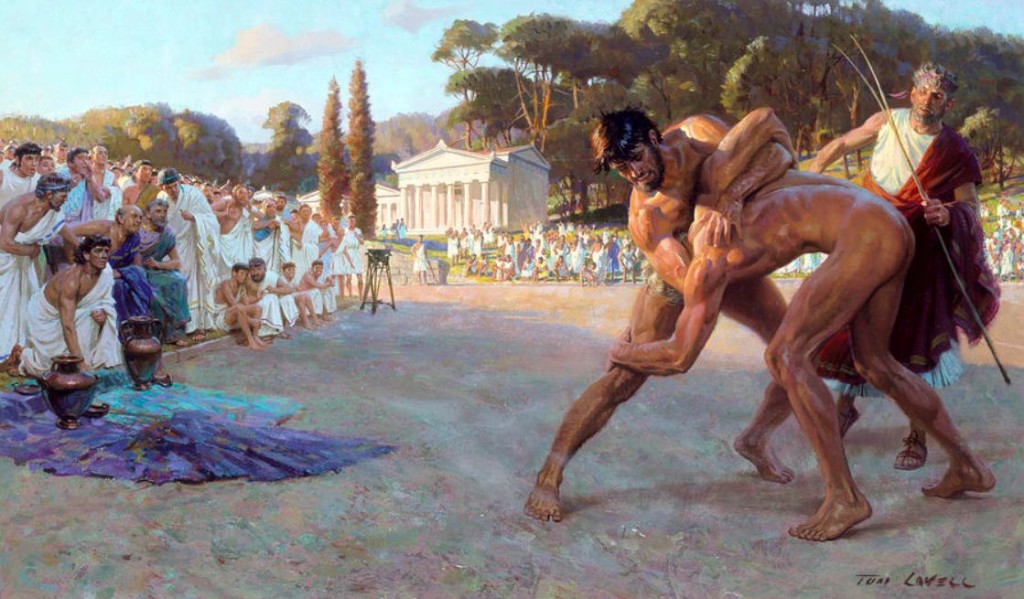

Heart of Fire is not only a story of love in war, it is also a story about sacrifice for the ultimate triumph – Victory at the Olympic Games.

In the book, and in this series on The World of Heart of Fire, we hear a lot about the ancient Greek ideals of ponos (toil), Eris Agathos (good strife), philoneikia (love of competing), and philonikia (love of winning).

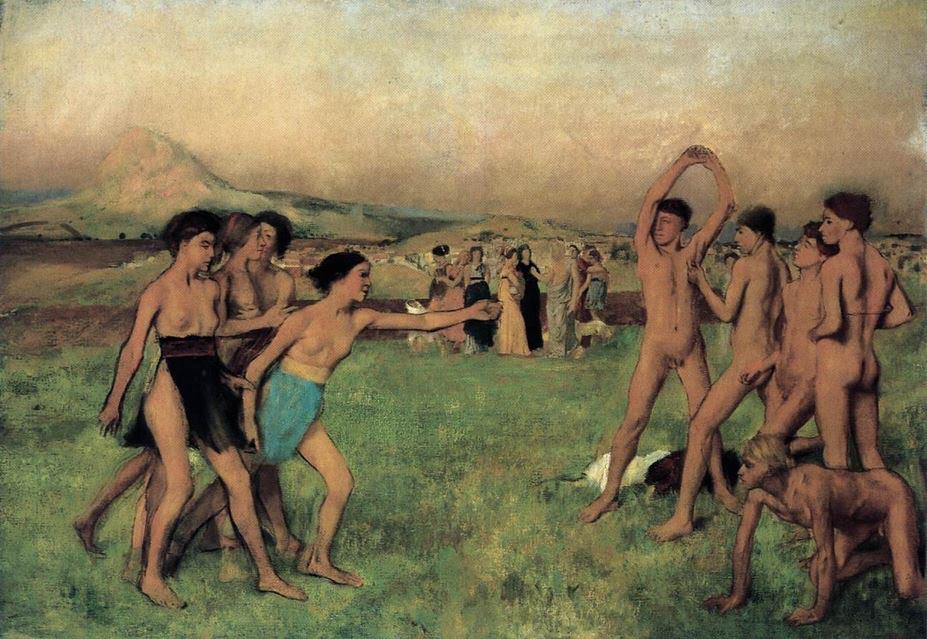

They were, as we have discussed before, central to the Greek psyche, and those who epitomized those ideals were praised and respected by all other Greeks.

And the respect and admiration that was given to an Olympic champion transcended war, politics, and the boundaries of one city-state. When the Gods, by their divine grace, sought to crown an athlete and warrior who has toiled long, and hard, and honestly, then few mortals dared gainsay them, especially when it came to the sacred Olympiad.

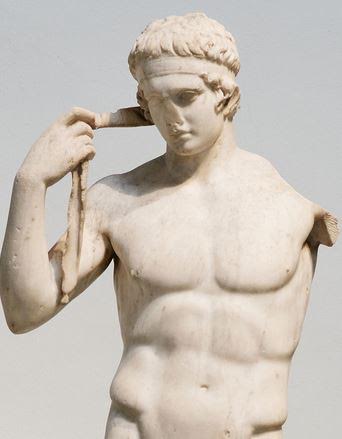

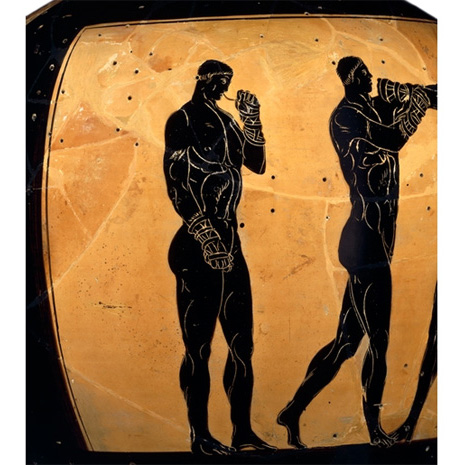

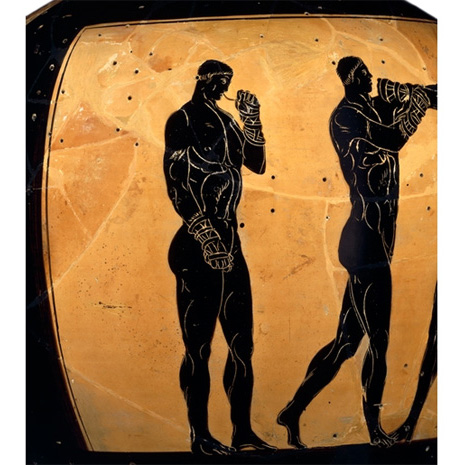

Athlete tying victory ribbon around his head

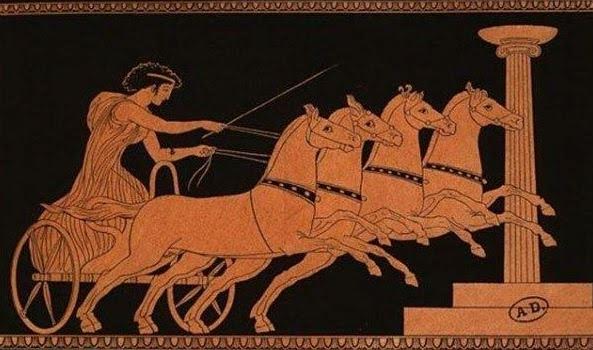

The praise of Olympic victors gave rise to a new form of art known as epinikion, which literally means ‘on victory’.

Epinikion art in ancient Greece took the form of poems, or ‘victory odes’, such as the one above, as well as marble or bronze sculpture.

First let us look at the epinikion poetry.

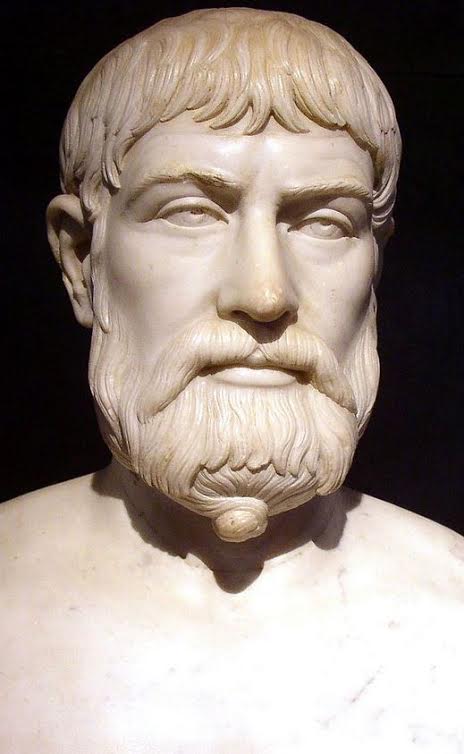

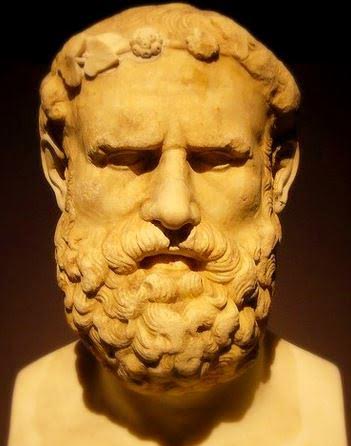

There were several poets who composed in the epinikion genre, but the most famous were Archilochus (680-645 B.C.), Simonides of Ceos (556-468 B.C.) who famously composed the epitaph to the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, and of course, Pindar (522-443 B.C.).

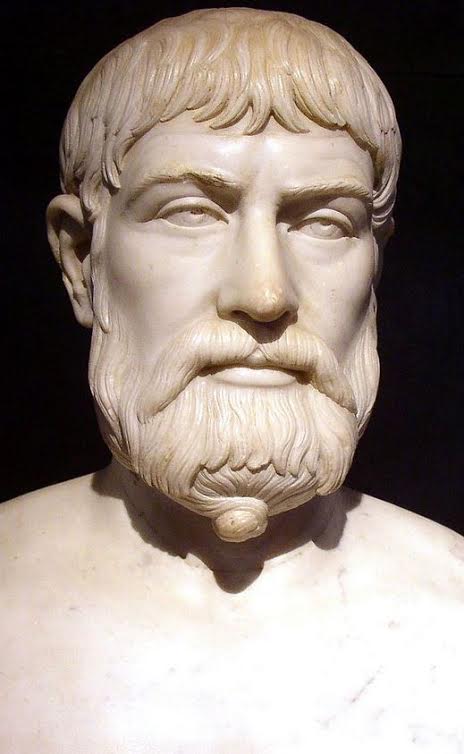

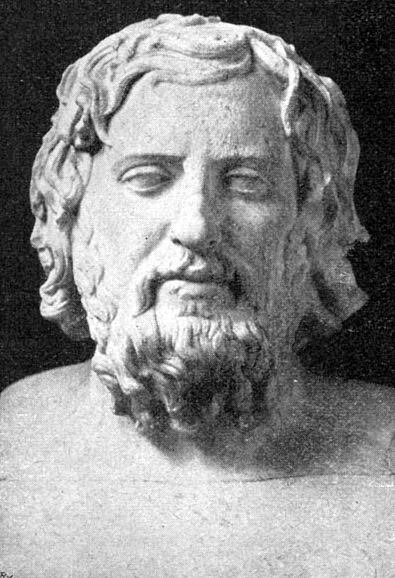

Pindar

Of all the epinikion poets of ancient Greece, Pindar is the most famous and well-known to us, partly because much of his work has been preserved. There are about thirty-eight of his victory odes which can still be read today. CLICK HERE to download a free copy of Pindar’s Extent Odes from Project Gutenberg.

There was a certain formula to epinikion poetry that began with a salute to the victor’s achievement, and then a mention of his pedigree, city, or relatives. There was emphasis on the effort and exertion, the all-important ponos demanded of athletic victory. Then the victory was incorporated into the values of the individual’s community.

Another ancient Greek ideal, that of philotimo, the love of honour, played an important role here as well. Loving honour meant bettering not only oneself, but also one’s community or city, the people around you, and the world in general.

When an Olympic victor was praised in epinikion poetry or sculpture, they were held up as an example, an inspiration if you will, to all other Greeks.

Now let Agesidamos, winner in the boxing at Olympia, so render thanks to Ilas as Patroklos of old to Achilles. If one be born with excellent gifts, then may another who sharpeneth his natural edge speed him, God helping, to an exceeding weight of glory. Without toil there have triumphed a very few. (Pindar Olympian Ode 11, for Agesidamos, winner in the boxing-match)

It became quite fashionable, among those who could afford it, to have a poet such as Pindar compose an ode to someone’s victory, such as the quote above. And Pindar himself travelled around doing this for a living. However, this should not detract from the power of the words of this poet.

Pindar’s words were so powerful and moving that when Alexander the Great sacked the city of Thebes for rebelling against Macedon, he ordered the home of Pindar to remain untouched, and the poet’s descendants unmolested, out of reverence for Pindar and his work.

The great epinikion poets’ work – Archilochus and Pindar especially – became so representative of the ideals of Olympic victory, that they became a part of the ceremonies at Olympia.

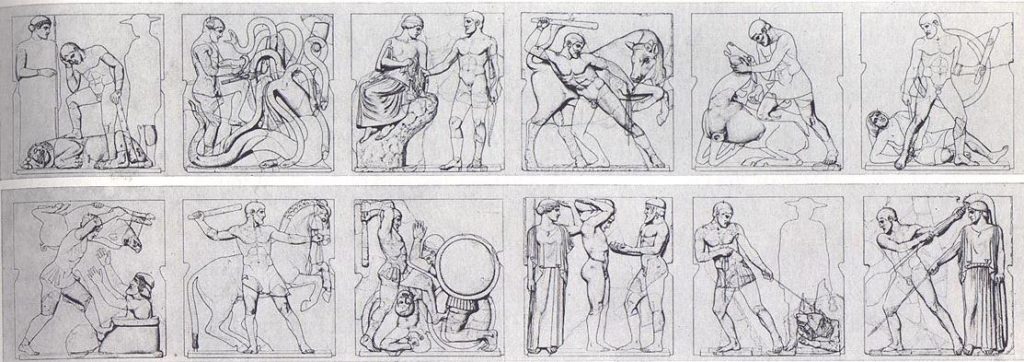

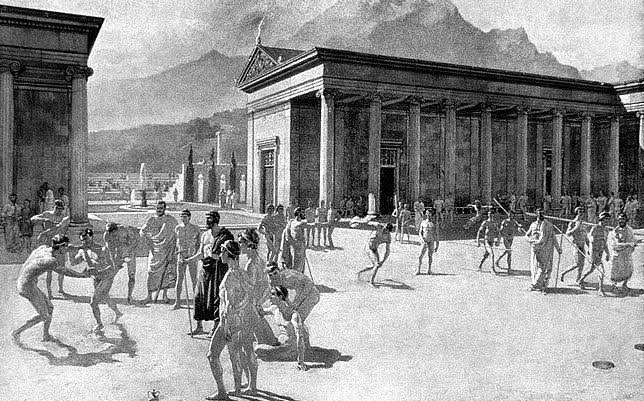

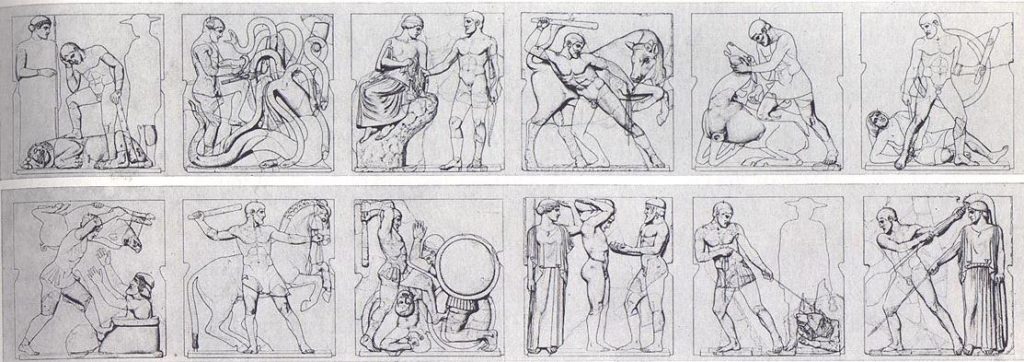

It is said that Archilochus’ Hymn to Herakles, one of the mythological founders of the Games, was sung during the crowning ceremonies at Olympia in the temple of Olympian Zeus. The temple, as it happened, was decorated with metopes illustrating the Twelve Labours of Herakles, the hero’s victories as it were.

Temple of Zeus Metopes

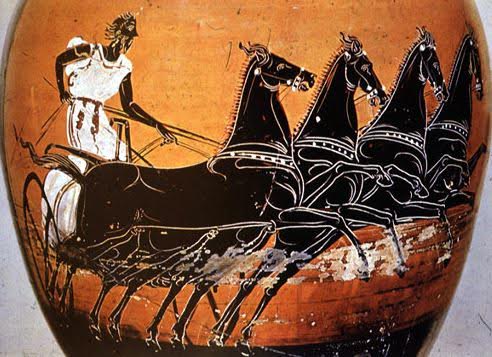

Epinikion sculpture also played a large part in the history and atmosphere of ancient Olympia, especially in the sacred heart of the sanctuary, the Altis.

It became the tradition that at Olympia, all victors were permitted to erect statues of themselves in the Altis. In a sense, this put them almost on equal footing with the Gods themselves. Some victors, including Kyniska of Sparta, had their victory bronzes in the temple of Zeus itself!

According to Pausanias:

The first athletes to have their statues dedicated at Olympia were Praxidamas of Aegina, victorious at boxing at the fifty-ninth Festival, and Rexibius the Opuntian, a successful pancratiast at the sixty-first Festival. These statues stand near the pillar of Oenomaus, and are made of wood, Rexibius of figwood and the Aeginetan of cypress, and his statue is less decayed than the other. (Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6.18.7)

If Pausanias is correct, then the first epinikion statues, not of bronze but of wood, would have been erected in the Altis around 544 B.C.

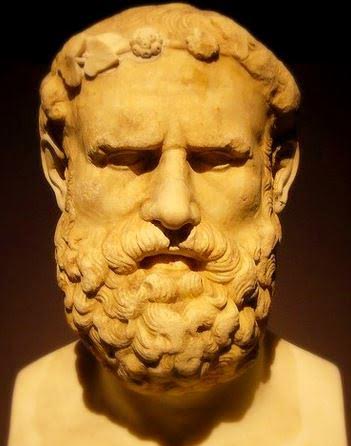

Epinikion poet, Archilochus

If that date is correct, then the tradition took hold quickly enough, and victors began to commission elaborate bronzes from some of the greatest sculptors of ancient Greece, artists such as Myron of Attika, Polykleitos of Argos, Kallikles of Megara, Naukydes of Argos and others.

Victory statues were erected by successive generations of families who had many Olympic victors in their ranks, the most famous being the Diagorids of Rhodes by Kallikles.

The bronze statues of Diagoras who won in boxing in 464 B.C., and also at all four crown games, stood six feet six inches in height.

…I too, sending to victorious men poured nectar, the gift of the Muses, the sweet fruit of my mind, I try to win the gods’ favor for those men who were victors at Olympia and at Pytho. That man is prosperous, who is encompassed by good reports. Grace, which causes life to flourish, looks with favor now on one man, now on another, with both the sweet-singing lyre and the full-voiced notes of flutes. And now, with the music of flute and lyre alike I have come to land with Diagoras, singing the sea-child of Aphrodite and bride of Helios, Rhodes, so that I may praise this straight-fighting, tremendous man who had himself crowned beside the Alpheus and near Castalia, as a recompense for his boxing… (Pindar, Olympian Ode 7; for Diagoras of Rhodes)

Modern bronze statue of Diagoras of Rhodes carried by his sons

The Diagorids of Rhodes were something of Olympic royalty, for not only did Diagoras claim victory, but also his sons Damagetos, Akousilaos, and Dorieus, as well as his grandson, Eukles, whose epinikion statue was also sculpted by Kallikles.

There was also the famous statue of Kyniskos of Mantinea, by Polykleitos of Argos, and another of the legendary Milo of Croton standing high on a round base and holding a pomegranate.

Goddess Nike, Ephesus (Wikimedia Commons)

Having one’s statues erected in the sacred Altis of ancient Olympia became something to be dreamed of by many, for in winning by the Gods’ grace, and being granted the right to erect a statues of oneself in the Altis, this was as close as one could get to immortality.

Someone who walked away from the Olympiad a victor was lauded across the Greek world, given free meals and drinks, sometimes exempt from taxation and more. The benefits of Olympic victory were indeed great, but none more so, I suspect, than knowing that the Gods had chosen you for victory.

It was a heady dream.

I tried to tap into this in Heart of Fire. The male protagonist, Stefanos of Argos, has a father who is a famous bronze smith of Argos, a centre of bronze artistry in ancient Greece. It is the dream of the father that an epinikion bronze be erected in the Altis of Olympia, and it is the son’s challenge to make that happen.

One supposes that many families of athletes had similar dreams of victory, of seeing the immortal likenesses of their fathers, sons, or grandsons erected in the forest of bronzes that stood all about the Altis, among the monuments of the gods and heroes of that place.

And every four years, when the Greek world would return to Olympia for the sacred games, the statues would remind men of those victors who had gone before, of the songs that were sung for them, and how the Gods had blessed them.

Statue of Nike, Goddess of Victory in the Archaeological Museum of Ancient Olympia

Thank you for reading, and stay tuned until next week for the final part in The World of Heart of Fire.