ancient Greece

Peloponnesian Eyrie – The Temple of Apollo Epikourios

Once it a while, I come across a site that strikes me as so magnificent and mysterious that I wonder why I didn’t know about it before, why it’s not spoken of by everyone with an inclination to ancient history.

If you’ve been reading my blogs you’ll know that I love to travel and have done so quite a bit in Greece. A few years ago, I was touring some of the major sites with friends and family – Delphi, Mycenae, Olympia etc. The biggies.

After Olympia, we drove back into the mountains of the Peloponnese. It was hot and bright, and the cicadas were whirring louder than I had ever heard before. As I was navigating a particularly treacherous series of mountain switchbacks, my father-in-law said that we should go south to Bassae.

“Bassae?” I said. “What’s there?”

“Some ruins,” he answered. “There is a temple of Apollo Epikourios.”

“Apollo Epi-what?” I half-answered, too focussed on the road to pronounce this new, strange word.

Admittedly my first thought was of Apicius and food – no matter that the Roman gourmet was about a six hundred or so years off. I was also starving at that moment!

So we turned south, into the teeth of even larger mountains.

Apollo Epikourios means ‘Apollo the Succourer’ or ‘Apollo the Helper’.

The epithet refers to Apollo’s role as a god of healing.

In the mid-seventh century B.C., Spartan warriors and plague came to the people of Phigaleia who were living in these high mountains. Many offerings in the form of weapons were found on site indicating that originally, in this place, Apollo was worshipped as a martial god. However, after escaping Spartan aggression and the plague of later years, Apollo became a ‘succourer’ or helper to the Phigalians.

In gratitude, the Phigalians commissioned the architect Ictinus to build the temple at Bassae.

This was no small thing. In Classical Greece, Ictinus was an A-list architect – he was one of the architects of the Parthenon and the great Temple of Mysteries at Eleusis.

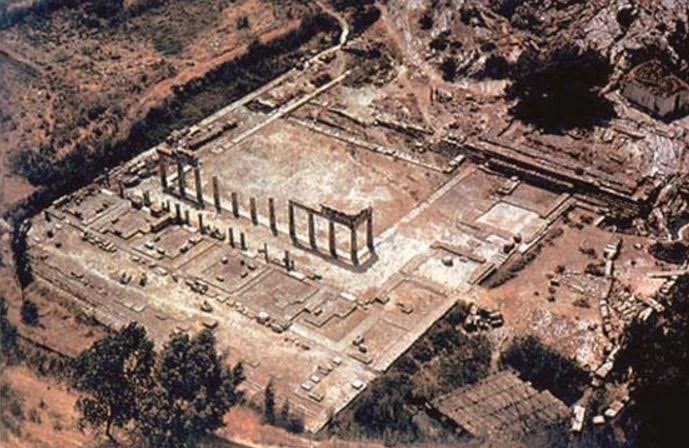

In the second century A.D. Pausanias visited Bassae and the temple there:

“Phigalia is surrounded by mountains, on the left by Mount Cotilius, while on the right it is sheltered by Mount Elaius. Mount Cotilius is distant about forty furlongs from the city: on it is a place called Bassae, and the temple of Apollo the Succourer, built of stone, roof and all. Of all the temples in the Peloponnese, next to the one at Tegea, this may be placed first for the beauty of the stone and the symmetry of its proportions. Apollo got the name of Succourer for the succour he gave in time of plague, just as at Athens he received the surname of Averter of Evil for delivering Athens also from the plague. It was at the time of the war between the Peloponnesians and the Athenians that he delivered the Phigalians also, and at no other time: This is proved by his two surnames, which mean much the same thing, as well by the fact that Ictinus, the architect of the temple at Phigalia, was a contemporary of Pericles, and built for the Athenians the Parthenon, as it is called.” (Pausanias)

When most tourists visit the Peloponnese today, they focus on sites like Mycenae, Epidaurus, ancient Corinth, and of course, Olympia. Why wouldn’t folks head for these places? They are magnificent sites that are all worth visiting – more than once.

However, if you are more adventurous and enjoy heading off the beaten path, the Peloponnese holds some hidden treasures that are not always prominently featured in guidebooks or on tour itineraries.

Bassae, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of those special, unsung places. Academics know about it but few tourists make it there. In fact, due to its remote location, it lay mostly forgotten until the early nineteenth century.

Our car whined up the steep mountain, higher and higher, the sunlight blinding. I felt like Icarus for a moment, driving up and up.

We finally levelled out and our eyes were met by a giant, white…tent.

“This is weird,” I remembered saying. I had no idea what lay beneath the white, sail barge structure.

We paid our minimal entry fee to the lady in the wooden site booth; she sat smoking and sipping an hours-old café frappé.

The mountain top was rocky and desolate, patched with hardy olive trees and shrubs. We made our way up the rocky path to the tent and stepped beneath the awning.

I couldn’t believe my eyes.

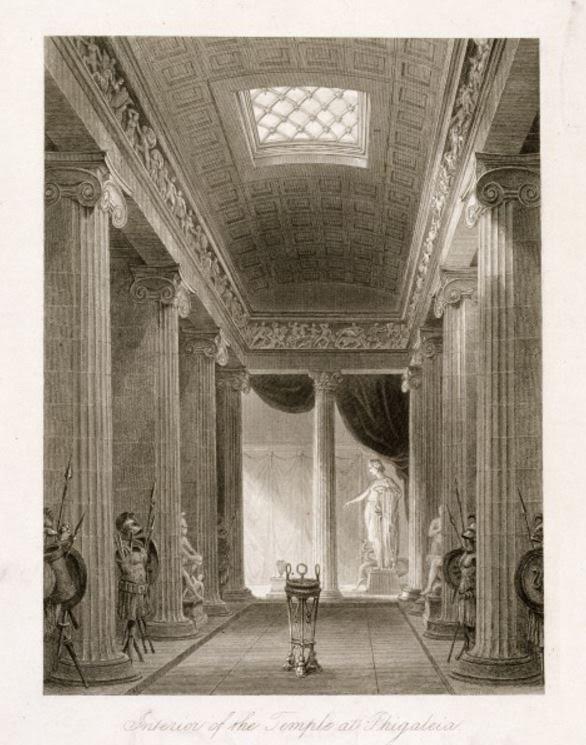

Up there, at what felt like the top of the world, was a magnificent stone temple, one of the most complete temples I had ever seen. The stone was cracked in many places, pounded by the elements for centuries in its eyrie.

But it was intact, columns and walls, foundations. A few stray rays of sunlight made their way into the shaded sanctum to illuminate the cella. We were the only visitors on site, and the main sense that invaded my person was pure awe.

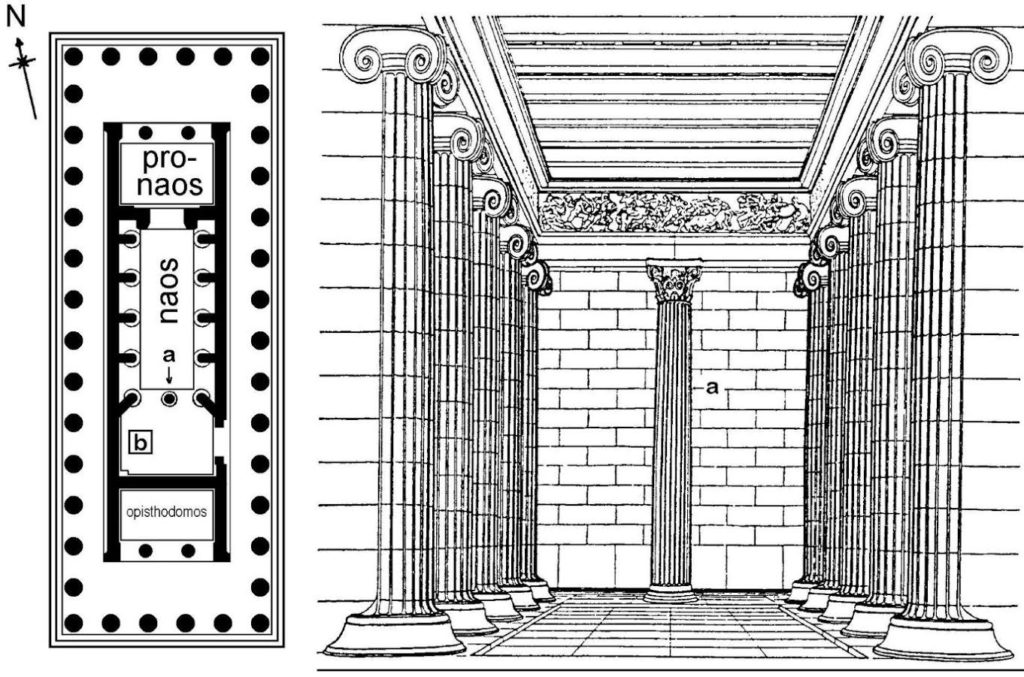

Bassae’s Temple of Apollo is a particularly important specimen, and not just because of the architect. It contained the earliest known example of a Corinthian capital which was displayed in the middle of the naos which was lined with Ionic columns. However, on the outside of the temple, the strength and support of the structure is provided by strong Doric columns, fifteen on each long side and six on the ends.

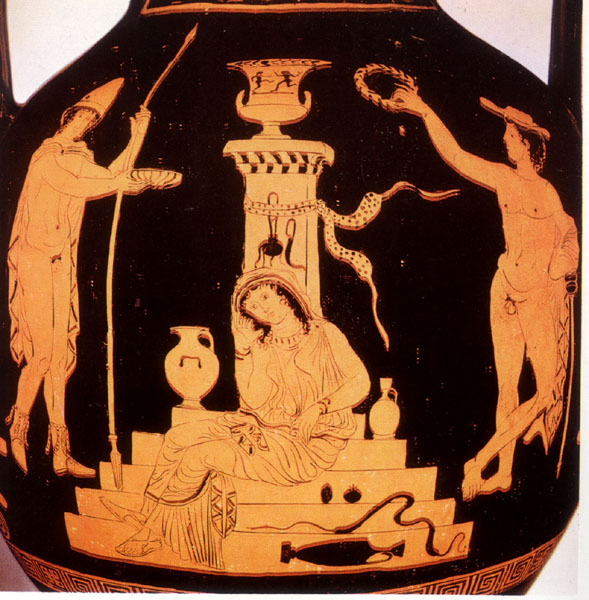

One of the things that make this temple unique is the incorporation of all three of the classical orders of columns. Also, the interior of the cella was ornamented with a series of beautifully detailed friezes of the Amazonomachy (Battle of the Amazons) and the Battle Centaurs and Lapiths.

You can see the Bassae Friezes at the British Museum where they are on display, far from their home at the top of that lonely mountain.

I think I was in such awed shock the first time that I didn’t quite realize what I was looking at.

Some places do that to you. The power of the place and setting can quite overwhelm the academic eye.

After wandering around the temple for a time, we went back outside into the sun to look at the surrounding countryside. These were some of the highest mountains in the Peloponnese and they stretched out in all directions. It is a quiet, contemplative atmosphere.

Outside the cicadas were louder than ever, but it is a sound I have come to associate with peace. The air was hot but dry and tinged with wild thyme that must once have been laid upon Apollo’s altar by the Phigalians.

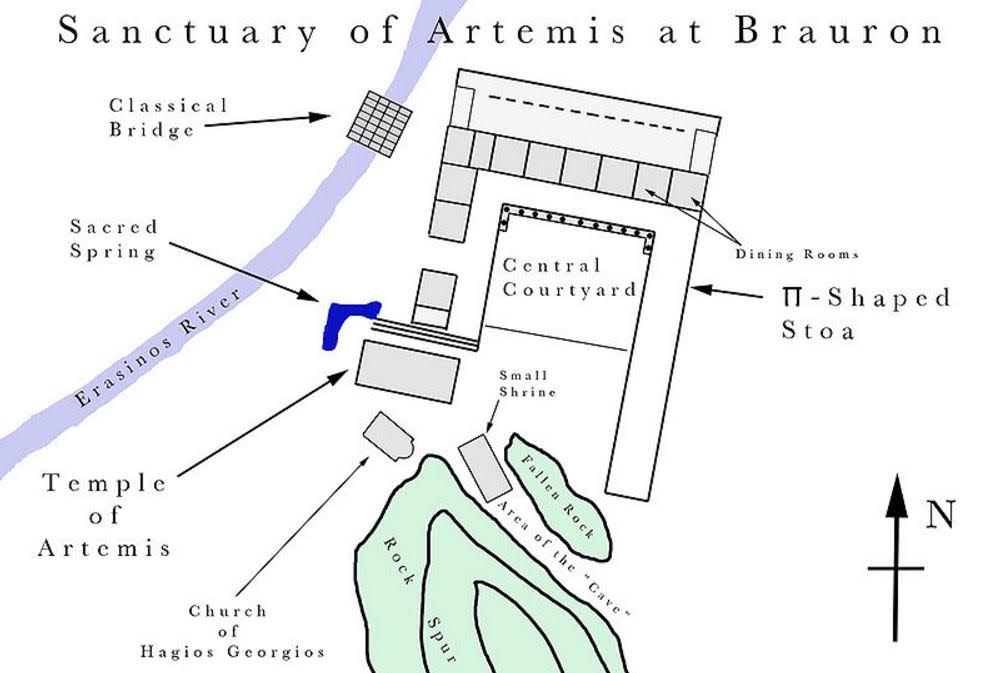

We stood in the sun and looked to Mount Kotilon where the map indicated that there was a Temple to Aphrodite and another to Artemis Orthasia, the ‘Protector of Small Children’.

These mountains are a place for gods.

I hope, one day, to return to Bassae. I want to circle the Temple of Apollo Epikourios and to remember the Phigalians who thanked him for his aid by building him this magnificent sanctuary in the sky.

* A useful source on the temple of Apollo Epikourios is:

The Temple of Apollo Epikourios: A Journey Through Time and Space published by the Greek Ministry of Culture Committee for the Preservation of the Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassai

The Elusive Etruscans

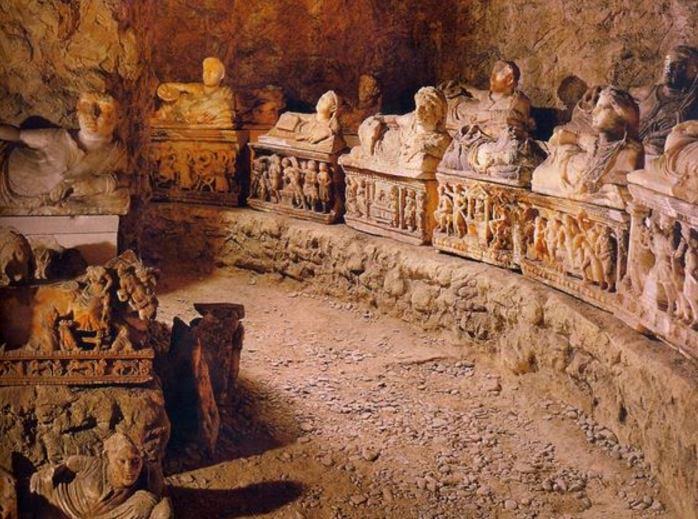

Recently, while excavating piles of my research on various topics, I unearthed some photos from a vacation in Tuscany back in 2002. These photos were of an Etruscan tomb just outside Castellina in Chianti.

The site was simple and unassuming, but it had a great impact on my imagination, so much so that I used it in some parts of Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra. On that trip, I started to learn more about the Etruscans who inhabited the Italian peninsula from roughly the Tiber to the Arno rivers and beyond, to the Po valley and Bologna.

So, my interest rekindled, I thought I would write a quick post on this fascinating people.

Not a great deal is known about the Etruscans, and I am by no means an expert, but from what I have seen and read, it’s a very interesting topic. Anyone who has studied ancient Greece and Rome will have had some contact with the Etruscans; the Greeks traded with them and were a great influence on Etruscan art and lifestyle, and Rome itself was ruled by Etruscan kings who brought that little backwater village by the Tiber out of the mud with a dash of civilization. In Tuscany itself, there are many sites where one can find remains of Etruscan civilization, places such as Cerveteri, Veii, Tarquinia, Volsinii, Volterra, Vulci and Arezzo.

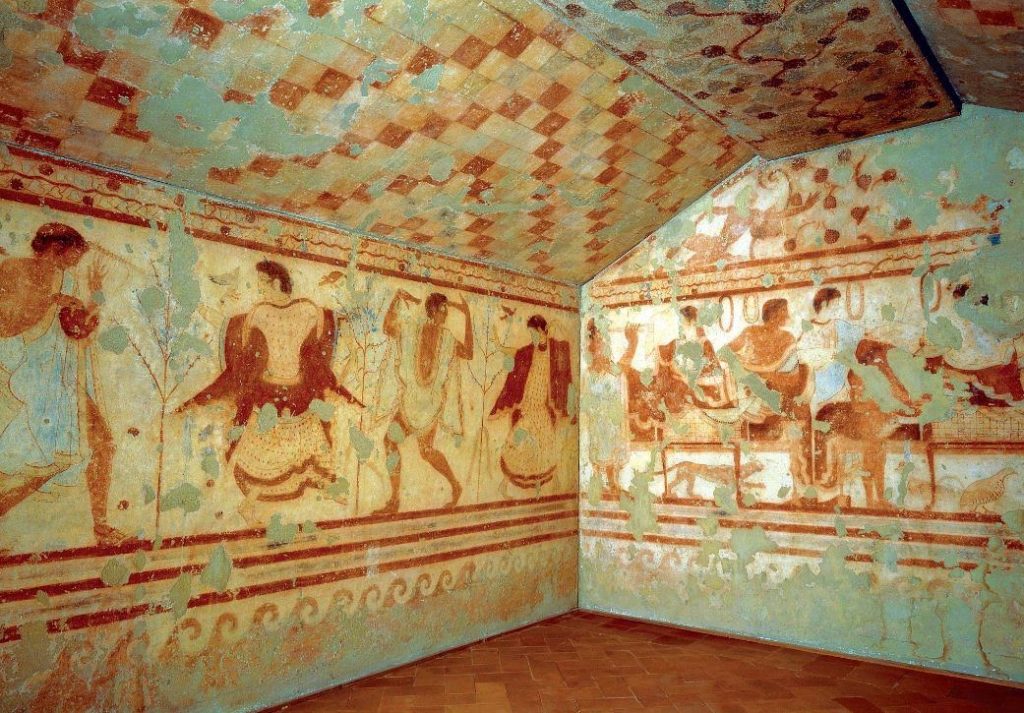

Much of what is known about the Etruscans and their lifestyle comes from their tombs where elaborate paintings of banquets and sporting events such as the Olympics have been found. Many grave goods have been found in the tombs and there is an excellent collection of finds at the Archaeological Museums of Bologna and Florence.

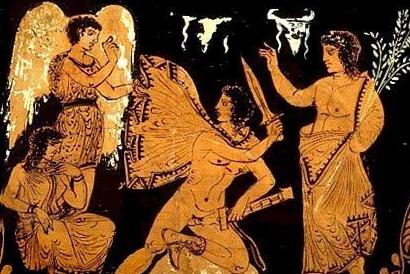

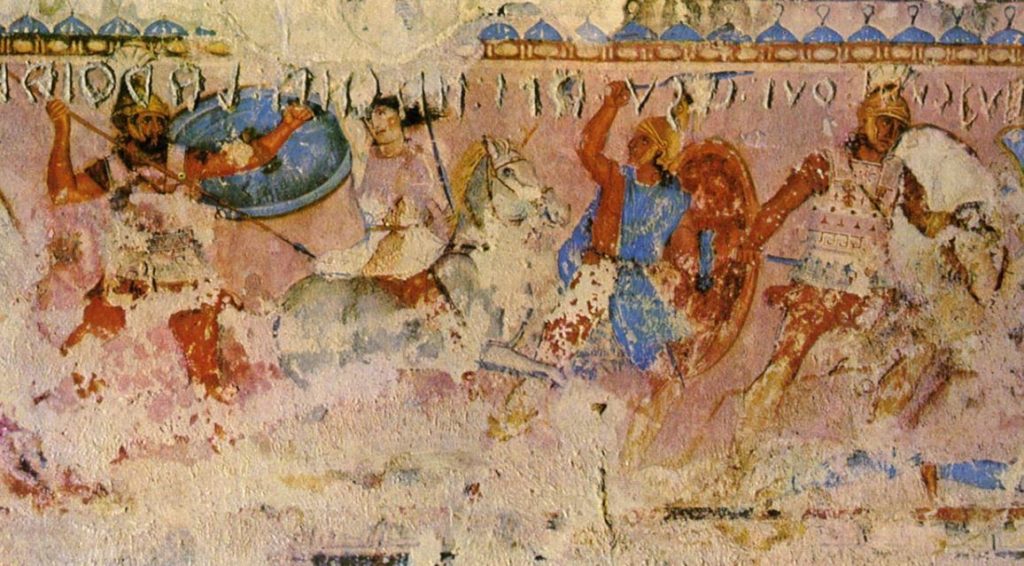

The Etruscans traded a great deal, and so had much contact with the Greeks from other parts of Italy, Sicily and mainland Greece. The walls of the tombs depict chariot races and elaborate banqueting scenes with diners reclining on couches, drinking wine from kraters and being entertained by musicians. The scene is like many an ancient Greek depiction with one marked difference: in Etruscan art, women were shown dining right alongside the men, drinking wine and enjoying conversation. This would have been scandalous to an ancient Greek, as women the other side of the Ionian sea were not permitted to be in attendance at banquets or symposia.

The Etruscans had their own rich culture and this is reflected in much of their bronze artwork and pottery. While some of it resembled ancient Greek art, or indeed was Greek art acquired through trade, much of it is quite unique. An excellent example of this is the famous bronze Chimera of Arezzo on display at the Florence Archaeological Museum.

There is much debate about the origin of the Etruscans in Italy with no consensus yet in sight. Some believe the Etruscans were an indigenous people, others that they came from Lydia in Asia Minor. As far as the Roman scene was concerned, the line of Etruscan kings began circa 616 B.C. with the reign of Tarquin the Elder who was a Corinthian Greek named Lucumo who lived in Tarquinia and married an Etruscan woman named Tanaquil. The two were shunned for a mixed marriage and so moved to the growing centre of Rome where Tarquin became the fifth king of Rome.

The Etruscans were famous for their understanding of augury and prophecy, religious practices which would be widely used in Roman life for hundreds of years. Etruscan augurs would read portents and the will of the gods in animal entrails and organs, and this skill impressed the Romans. The Etruscans not only complemented Roman religious practices, but also helped to improve Roman building practices and it is to them that the Romans owe their talent for building aqueducts and sewers.

At the peak of their power and influence, the Etruscans were the dominant people of central Italy. They were however, never a truly unified nation and, like the Greeks who had influenced them and traded with them, their city-states never stopped fighting amongst themselves. With the Romans growing in strength and skill to the South, and the Celts expanding in the North, the Etruscans were in a superbly unenviable position and could not hold sway for long.

The last Etruscan king of Rome, Tarquin the Proud, who according to Livy took the throne by force and ruled through fear, was narrowly defeated in a series of battles between Etruscan allies and the Romans, led by Lucius Iunius Brutus. Many died on both sides, but Tarquin lived through the day and, though no longer King of Rome, lived out his days in exile in Tusculum. The wheels had been set in motion and Rome had become a Republic.

Of course, when I walked into the cypress-crowned tomb outside Castellina in Chianti years ago, I knew nothing of Etruscan history, nor how fascinating it really is. This short blog post is a tiny scratch on the surface, a mere taste – there is so much more to learn. There are not many books (fiction or non-fiction) on the subject, at least not in English. As far as historical fiction/fantasy, two great reads are Steven Saylor’s Roma, part of which takes place during Rome’s infancy, and the other book is Ursula K. Le Guin’s wonderfully woven tale, Lavinia, which looks at the mythical foundation of Rome with the arrival of Aeneas after the Trojan War.

If you ever find yourself in Italy, I highly recommend the archaeological museums of Florence and Bologna where you can see Etruscan artefacts for yourselves, and it goes without saying that visits to the archaeological sites mentioned are well worth the adventure. Just remember that snakes, as well as tourists, like nothing more than a dark, damp tomb in summer time.

Thank you for reading.

*If anyone has a favourite source for information on the Etruscans, please do share it in the comments below so that everyone can check it out!

DELOS – A Visual Odyssey

Legend has it that Leto, the beautiful Titaness, travelled the world over as her belly swelled with the offspring of cloud-gathering Zeus. No town or village, forest or mountain fastness would welcome her with the great goddess Hera pursuing her to the ends of the earth. Rest upon land was forbidden to the expectant mother who fled her tormentors from the great forests of Hyperborea to the salt sea. When Leto’s time was near, an island with no roots welcomed her.

…so far roamed Leto in travail with the god who shoots afar, to see if any land would be willing to make a dwelling for her son. But they greatly trembled and feared, and none, not even the richest of them, dared receive Phoebus, until queenly Leto set foot on Delos… (Homeric Hymn 3 to Apollo)

The Sacred Harbour of Delos and part of the archaeological site

There are many sacred places in the world, places that have been the centre of worship for ages. They are places where history and myth vibrate together, where they can be felt, and touched.

The Aegean island of Delos is such a place.

This post isn’t a history lesson. It’s more of a visual journey, something for your senses to enjoy.

At the eye of the group of islands known as the Cyclades, this little island was a centre of religion, inspiration, and trade for millennia. Empires went to war over control over this small place just five kilometers long and thirteen-hundred meters wide.

The House of the Dolphins

Delos has been occupied, as far as we know, since the third millennium B.C. As the midway point between the Greek mainland, the western Aegean islands, and the Ionian coast, it was the perfect stopping point for ship-bound traders.

However, the main reason for the popularity of Delos, for its sanctity, was that it was believed to be the birthplace of two of the most important gods of the Greek and Roman pantheons – Apollo and Artemis.

To reach Delos today you must take a boat from the nearby Cycladic island of Mykonos. It is a choppy ride and not for those without sea legs. The Cyclades are in a windy part of the Aegean. However, the short odyssey to get there is well worth it. Once you come out of the waves and into the Delos Strait between the island of Rhenea and Delos itself, the waters welcome the visitor and Delos appears like a hazy jewel in a brilliant turquoise sea.

Part of the residential district of Delos

Delos is not just another archaeological site to be seen hurriedly through the lens of a camera. For those open to it, as soon as you set your foot on the path from the ancient ‘Commercial Harbour’ to the upper town, you know this place is different. This is a place to be felt with all your senses.

Apollo’s sun beats down with intense heat, and the hot Aegean winds wrap themselves about you at every turn. The voices of the past are loud indeed, be they of priests or pilgrims, merchants or charioteers, theatre patrons or performers, the rich or poor. Everyone came to Delos for all manner of reasons, for thousands of years.

Ruins along the Sacred Way

To preserve the purity of the place in ancient times, it was forbidden for anyone to be born or to die on Delos. Those who were involved in either of these acts were sent across the strait to Rhenea to do so. As the birthplace of important gods, this was taken very seriously.

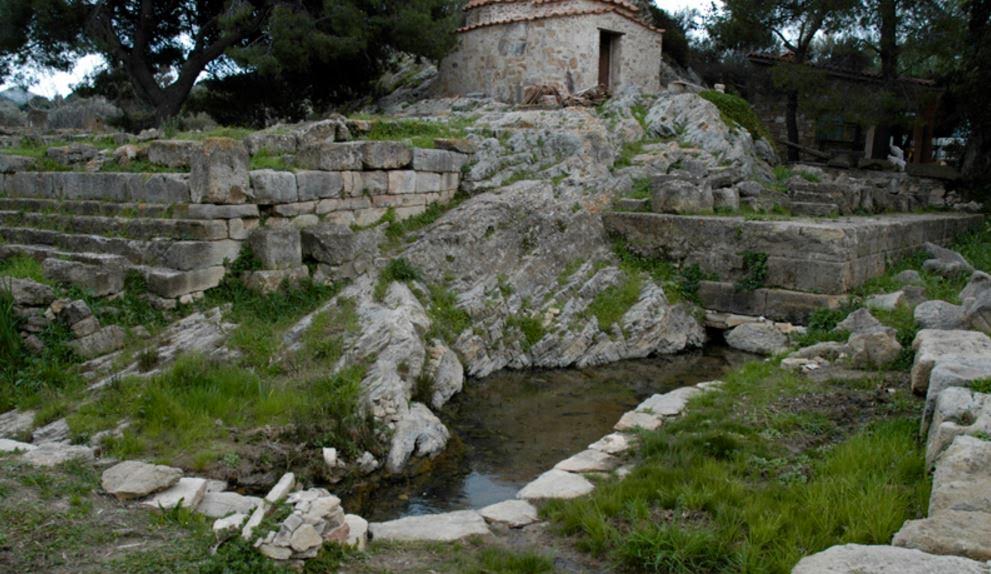

The Palm and the Sacred Lake

…the pains of birth seized Leto, and she longed to bring forth; so she cast her arms about a palm tree and kneeled on the soft meadow while the earth laughed for joy beneath. Then the child leaped forth to the light, and all the goddesses washed you purely and cleanly with sweet water, and swathed you in a white garment of fine texture, new-woven, and fastened a golden band about you. (Hymn to Delian Apollo)

The usual visitor might be led directly to the small museum on-site where several artefacts are on display. Others feel themselves pulled in the direction of the place that made Delos famous. The Sacred Lake, where Leto is said to have laboured for nine days when giving birth to Apollo and Artemis, is still there with its magnificent palm swaying in the sea breeze. The lake is drained now, and the palm is a distant ancestor of the original, but it is still a marvel to stand in a place revered for ages. On a nearby hill, the nine Delian lions stand guard over the birthplace of the gods, ever watchful.

Mount Cynthus

Delos was not just a quiet place for religious reflection. Indeed, it was very busy and at one point had a population of about 25,000 people. It was covered with sanctuaries and temples, monumental gates and colossal statues, stoas, shops, homes, theatres, stadia and agora. And above it all was mount Cynthus, 112 meters high, where the Archaic Temple of Zeus looked down over the birthplace of his son and all the mortals coming to do them homage.

If you stroll about the island you will be greeted by something new around each corner; a different view of the sea, ancient homes with some of the most beautiful mosaics ever found open to the sky, the ruins of a once-beautiful theatre, or even something as simple as a stretch of marble paving slabs from whose cracks red, purple and yellow flowers sprout to paint the scene.

Temple of Isis in the Sanctuary of Egyptian Gods

Delos was a meeting place of many deities, not only Apollo and Artemis. There were also temples to Zeus, Athena, Poseidon, Hera and many others of the Greek Pantheon. On the Island of Delos there were also sanctuaries to Syrian, Egyptian and Phoenician deities. Near the stadium area, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of a Jewish Synagogue. All were welcome to make offerings, worship, work and trade on this tiny rock-of-an-island which, by the 1st century B.C., was one of the great commercial centres of the world.

As one walks around the site today, it is not necessarily the voices of trade and craftspeople at their daily work that one is reminded of.

The shops have long since closed their shutters and turned to dust. The treasuries have been looted, and subsequently crumbled. Grass and wild flowers sprout from between the paving slabs of the Sacred Way where asps warm themselves beneath the rays of Apollo’s light.

One of the Delian Lions overlooking the Sacred Lake

In truth, it’s difficult to describe in words the feeling one gets while cutting a meandering path among these ancient ruins. Delos is a place of light and colour and ancient beauty, an omphalos of the Aegean to which travellers have been drawn for ages.

For myself, there is an overwhelming sense of awe and absolute peace that creeps over me whenever I visit this place. It’s not always an easy task to shut out the groups of tourist hoards that descend upon this unassuming rock by the boatload. However, if you can manage the journey there, to break away from the masses, you will be treated to an experience in which you will delight in myriad shades of blue and pristine white, hot Aegean breezes and the loving light of the sun.

Most of all, you will stand still and wonder at the sight of a swaying palm, that one spot on the island where gods were said to have been born, and which earned this place called Delos renown for all time.

…queenly Leto set foot on Delos and uttered winged words and asked her… “Delos, if you would be willing to be the abode of my son “Phoebus Apollo and make him a rich temple –; for no other will touch you, as you will find: and I think you will never be rich in oxen and sheep, nor bear vintage nor yet produce plants abundantly. But if you have the temple of far-shooting Apollo, all men will bring you hecatombs and gather here, and incessant savour of rich sacrifice will always arise, and you will feed those who dwell in you from the hand of strangers…

(Hymn to Delian Apollo)

A picture is indeed worth a thousand words, so, if you would like to see more, just continue scrolling down to continue the visual Odyssey.

Thank you for reading…

The nine Delian Lions keep a timeless watch over the Sacred Lake

Part of the archeological site of Delos. Excavations continue as most of the island remains to be uncovered

Terrace of a Delian house overlooking the Commercial Harbour

Mosaic at the House of the Dolphins

Doorway to the back of the theatre

The ancient theatre of Delos. The artistic competitions of the ‘Delia’ were performed here

Island cisterns where rain water was gathered

Alleyway among the ruins of Delos

Mosaic in the residential quarter

Mosaic waves open to the sky

Statues in the House of Cleopatra

Ruins near the harbour

Remains of colossal statue of Apollo (the torso)

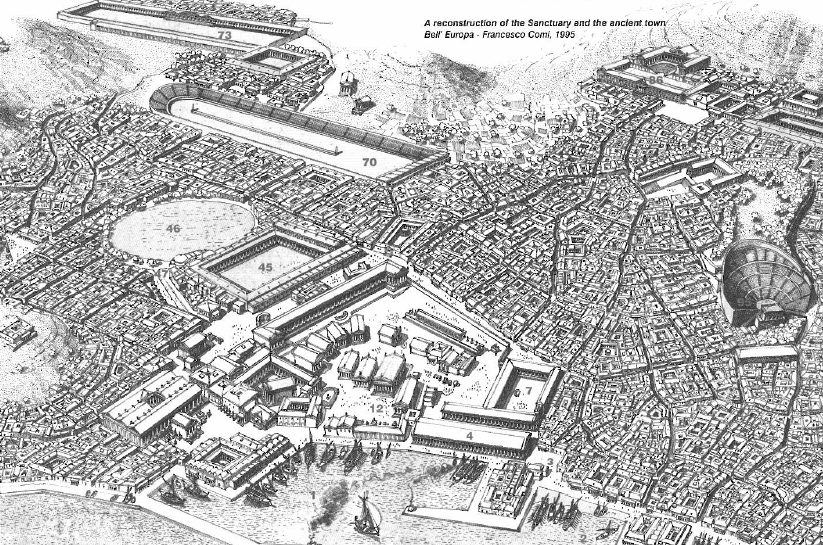

Artist rendering of ancient Delos – Francesco Comi, 1995

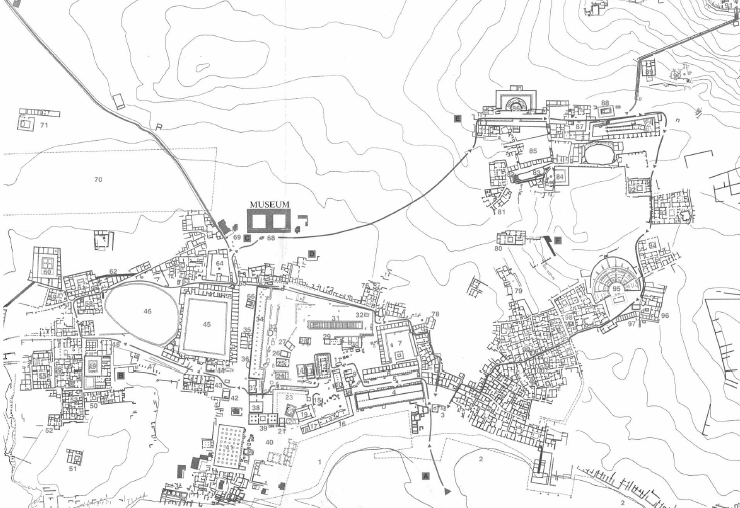

Map of the Archaeological site of Delos Edition sponsored by the Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Culture and the European Community (3rd CSF 2000-2006)

To Delos in another light, other than the parched, tourist-packed summer landscape we are familiar with, check out the beautifully shot video below, directed by Andonis Theocharis Kioukas. In this video, you see Delos in the fullness of spring, quiet, green, with myriad colours bursting from among the ruins.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8nTyppBJVso

The Tragedy of Herakles

Alas! alas! lament, O city; the son of Zeus, thy fairest bloom, is being cut down. Woe is thee, Hellas! that wilt cast from thee thy benefactor, and destroy him as he madly, wildly dances where no pipe is heard.

She is mounted on her car, the queen of sorrow and sighing, and is goading on her steeds, as if for outrage, the Gorgon child of Night, with hundred hissing serpent-heads, Madness of the flashing eyes. Soon hath the god changed his good fortune; soon will his children breathe their last, slain by a father’s hand. (Euripides – Herakles)

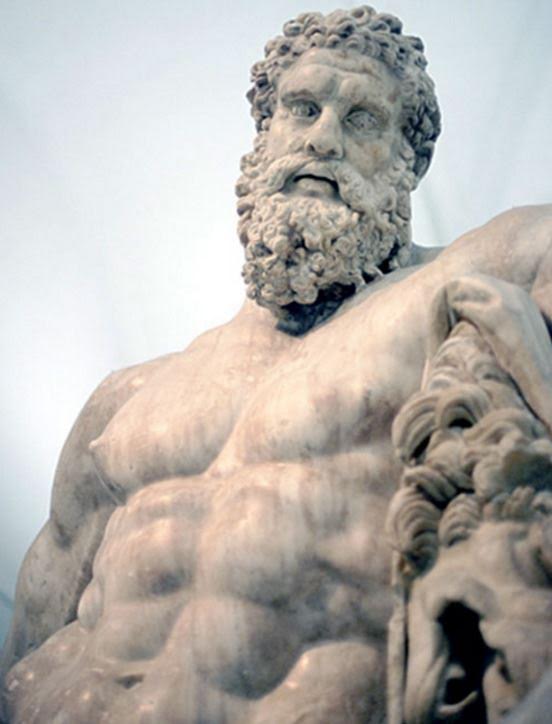

In Part I of this series on Herakles, we looked at his triumphs, the Twelve Labours that set him down on the papyrus pages of ancient history as the greatest hero. He was a man of great strength, appetites, perseverance, and emotion. He traveled the world achieving feats that would have defeated any other man of his time.

The tales of Herakles’ heroics have inspired for centuries.

But, as with all tales from ancient Greece, triumph and tragedy go arm in arm in the hero’s life.

The tragedy of Herakles’ life actually began, as mentioned in Part I, before his twelve labours, when he was driven mad by Hera and ended up killing his wife, Megara, and their children.

Ah me! why do I spare my own life when I have taken that of my dear children? Shall I not hasten to leap from some sheer rock, or aim the sword against my heart and avenge my children’s blood, or burn my body in the fire and so avert from my life the infamy which now awaits me? (Euripides – Herakles)

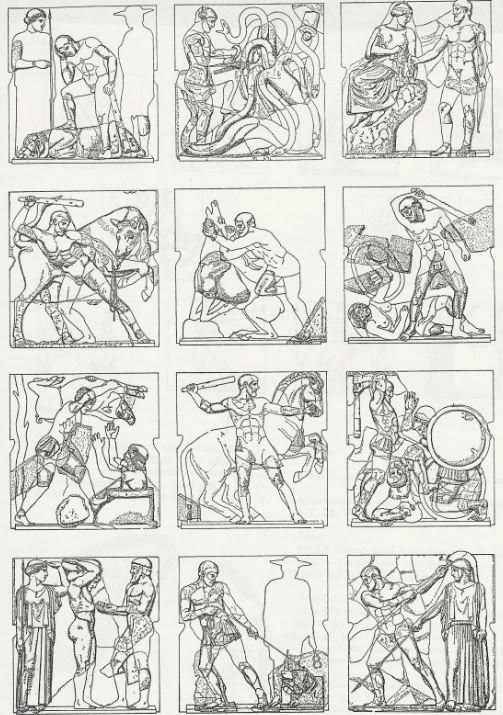

Metopes of the 12 Labours adorning the Temple of Zeus at ancient Olympia

The twelve labours were a part of his atonement for this horrifying crime.

One would have thought that with the Labours he had paid the price, but that would be too easy. As we shall see in this brief post, Herakles would be made to suffer and live a life of rage and pain till the end of his days. There would be no sitting on his laurels.

As the following passage shows, even in the fiery realm of Hades, Herakles’ shade is dark and menacing, someone even the dead are afraid of:

Next after him I observed the mighty Herakles – his wraith, that is to say… From the dead around him there arose a clamour like the noise of wild fowl taking off in alarm. He looked like black night, and with his naked bow in hand and an arrow on the string he glanced ferociously this way and that as though about to shoot… (Homer – The Odyssey)

Herakles is often known as ‘Alexikakos’, the ‘averter of evil’, but this proved impossible when it came to himself.

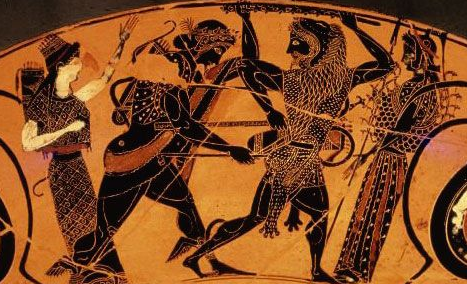

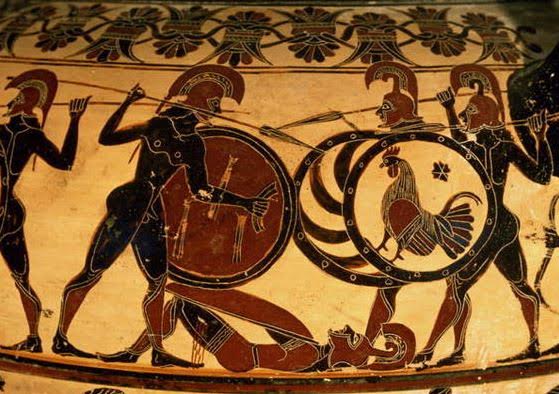

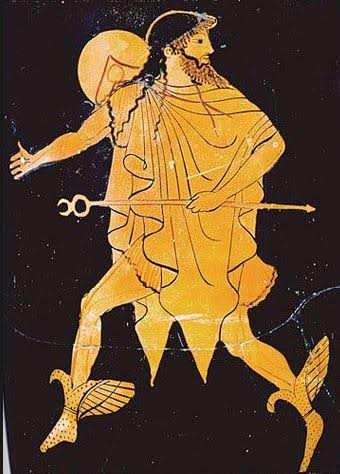

Apollo and Herakles fighting over the Delphic Tripod

He was often helping others, such as when in Hades, he found Theseus, another hero, in his punishment, and raised him up to be free back on Earth.

But did others often help Herakles?

Sometimes. During his labours, he did receive aid from Athena, Atlas, Helios, and from his cousin, Iolaus, but most of the time, he had to go it alone.

After the Twelve Labours, Herakles seems to have become a sort of fallen hero.

When he kills Iphitus, the son of Eurytus who had refused to give the hero the hand of his daughter, Iole, he becomes diseased because of the murder; this is a punishment from the Gods.

Herakles goes to the Oracle at Delphi, but the Oracle refuses to answer him this time. In a rage, Herakles attempts to steel the sacred tripod which Apollo tries to take back.

Herakles and Omphale

Zeus steps in to stop the quarrel between his two sons, and the Oracle complies in giving Herakles an answer; he must sell himself into slavery for three years.

He is ‘bought’ by Omphale, a Queen of Lydia. It is during this time of servitude that Herakles joins the Argonauts, one of the most famous crews in history, in their search for the Golden Fleece. Even here, the hero is not allowed to be a part of the Argonauts’ success as he is left behind in Mysia to search for his friend, Hylas, who was abducted by water Nymphs.

The Argonauts

Once his service to Omphale was settled, Herakles seems to have set out on a fit of vengeance to settle some old debts.

He raised an army with Telamon and sailed to Troy where he captured the city and killed King Laomedon. He also killed all the Trojan princes too, except Priam.

Herakles about to kill Laomedon

Other acts of revenge included killing King Augeas of Ellis, and his sons, who had refused to pay up for the cleaning of his stables.

Herakles then marched to Pylos to face Neleus who had refused to purify him of the murder of Iphitus who was a guest of Herakles’ in Tyrins at the time. Herakles slew Neleus and all twelve of his sons except Nestor who was away at the time, and who would be a part of the later Trojan War.

On top of all this, Hera did not relent in her persecution of Herakles. She sent storms to pursue the hero, but it is at this point that Zeus finally says enough is enough. The king of the gods suspends Hera from Mt. Olympus with anvils tied to her feet.

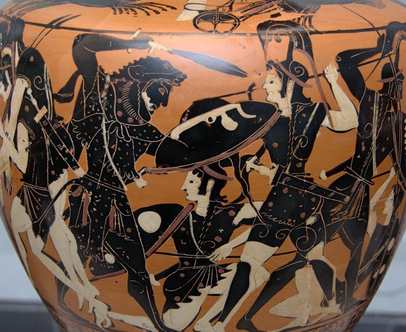

Battle of the Gods and Giants – Siphnian Treasury at Delphi)

Then the Gods themselves need Herakles’ help at Phlegrae, in Thrace. The Battle of the Gods and Giants is one of the most widely depicted events in ancient Greek art. It is here that Herakles played a key role in aiding the Gods to victory.

But, exhaustingly, sadly, that is not the end for Herakles. It is not time to rest. He continues with his acts of vengeance, among them the sacking of Sparta, and the killing of Hippocoon and all his sons.

Our fallen hero has much blood on his hands at this point, but finally, after so much turmoil, he finds a measure of happiness in Calydon where he marries Deianeira, the daughter of King Oeneus. She is also the sister of Meleager, whom Herakles had spoken with in Hades on his twelfth labour.

Herakles and Deianeira

While in Calydon, Herakles helps his father-in-law to defeat his enemies. He and Deianeira have several children together. She is beautiful, virtuous, and loves her husband dearly.

But the idyllic time is short-lived. At one point, Herakles accidentally kills King Oeneus’ cup bearer, and so he, Deianeira, and their children are forced to leave Calydon. They settle in Trachis.

On one part of their journey, they must cross the river Evenus. While he is crossing the river, it seems that Herakles entrusts his wife to the centaur, Nessus, who tries to rape her.

Herakles’ rage takes over and he kills Nessus with one of his arrows dipped in the blood of the Hydra.

As Nessus lays dying, he whispers to Deianeira that his own blood is a powerful love charm, and that she should take some and keep it hidden if ever she needed it.

Deianeira saves some of the centaur’s blood.

While in Trachis, Herakles helps his host King Ceyx, to defeat his enemies. It seems that kings were happy to host Herakles if he helped them to defeat their foes. Herakles then helped Aegiaius to fight and defeat the Lapiths, and in that conflict, he killed Cycnus, the son of Ares, in single combat, as well as wounding Ares himself.

Iole

Bent on vengeance once more, Herakles raises an army and marches against Eurytus who had refused him the hand of Iole. Herakles takes the young girl as his concubine and, along with many prisoners, brings her back to Trachis.

The springs of sorrow are unbound,

And such an agony disclose,

As never from the hands of foes

To afflict the life of Heracles was found.

O dark with battle-stains, world-champion spear,

That from Oechalia’s highland leddest then

This bride that followed swiftly in thy train,

How fatally overshadowing was thy fear!

But these wild sorrows all too clearly come

From Love’s dread minister, disguised and dumb.

(Sophocles – The Women of Trachis)

Deianeira mourning

Deianeira realizes that her husband loves the quiet, beautiful Iole, and decides to use the supposed ‘love-charm’ of the centaur’s blood.

At this time, Herakles was in Euboea sacrificing to Zeus for his many triumphs over his enemies. He sent to Deianeira for his finest robe for the ceremonies. With this act of piety, Herakles seals his doom, for Deianeira smears the blood of Nessus on the robe thinking that it will make Herakles love her again.

The blood begins to eat into Herakles’ flesh like acid, killing him slowly.

When Deianeira hears from their son, Hyllus, what she has done, she kills herself in despair. The nurse to the Chorus:

When all alone she had gone within the gate,

And passing through the court beheld her boy

Spreading the couch that should receive his sire,

Ere he returned to meet him,—out of sight

She hid herself, and fell at the altar’s foot,

And loudly cried that she was left forlorn;

And, taking in her touch each household thing

That formerly she used, poor lady, wept

O’er all; and then went ranging through the rooms,

Where, if there caught her eye the well-loved form

Of any of her household, she would gaze

And weep aloud, accusing her own fate

And her abandoned lot, childless henceforth!

When this was ended, suddenly I see her

Fly to the hero’s room of genial rest.

With unsuspected gaze o’ershadowed near,

I watched, and saw her casting on the bed

The finest sheets of all. When that was done,

She leapt upon the couch where they had lain

And sat there in the midst. And the hot flood

Burst from her eyes before she spake:—‘Farewell,

My bridal bed, for never more shalt thou

Give me the comfort I have known thee give.’

Then with tight fingers she undid her robe,

Where the brooch lay before the breast, and bared

All her left arm and side. I, with what speed

Strength ministered, ran forth to tell her son

The act she was preparing. But meanwhile,

Ere we could come again, the fatal blow

Fell, and we saw the wound. And he, her boy,

Seeing, wept aloud.

(Sophocles – The Women of Trachis)

Back on Euboea, Herakles, in great pain, knows it is his time and has a pyre built for himself on Mount Oeta. He climbs up onto the pyre and asks for help lighting it.

But no one will help the hero.

Poor Herakles…

Finally, a passing shepherd by the name of Poeas, who is looking for his sheep, decides to help Herakles. As a gift, Herakles gives Poeas his great bow and arrows.

Now my end is near, the last cessation of my woe. (Sophocles – The Women of Trachis)

As the pyre burned, thunder raged in the sky, and Herakles is taken to Mt. Olympus to join the ranks of the Immortals.

Apotheosis of Herakles (Francois Lemoyne)

After all the pain and hatred, he and Hera are finally reconciled, and he is married to Hebe, the Goddess of Youth.

As an eternal monument to his long-suffering son, Zeus sets Herakles in the stars where he kneels to this day.

Herakles Constellation

Before I had written these posts, I had never looked at the triumph and tragedy of Herakles as a whole. I had grabbed at bits and pieces of his life for inspiration, for short story, for entertainment, like a literary carrion crow.

But the epic life and journey of Herakles, as a single life lived, leaves me breathless and shaking with emotion.

After his initial madness and the slaying of Megara and his children, death and the burning halls of Hades might have been an easier path than the one he took.

I don’t think immortality was ever Herakles’ goal.

How might Herakles have felt, remembered as he is after his apotheosis?

To have travelled so far, to have lived, and loved, and fought, and conquered, and suffered enough for many lifetimes…is a thing unimaginable to this mere mortal as he types these words.

Herakles’ life is not only the stuff of legend, it is the essence of art, and poetry, of lesson, and of inspiration.

As Theseus, in Euripides’ play, says to Herakles when he finds his friend mourning his dead wife and children:

Yea, even the strong are o’erthrown by misfortunes.

Thank you for reading.

If you would like to read more, follow the links below to get free downloads of the following works:

The Women of Traches and Philoctetes by Sophocles

Alcestis and Heracles by Euripides

For coherent histories of Herakles’ life you can view the works of both Apollodorus and Diodorus Siculus on theoi.com

The Triumphs of Herakles

Some of the most timeless stories in western literature are about the heroes of ancient Greece.

For millennia people have been inspired by Perseus, Jason and the Argonauts, Theseus, Achilles and Odysseus. Many an ancient king and warrior has tried to emulate the actions and personae of these heroes, and even claimed descent from them.

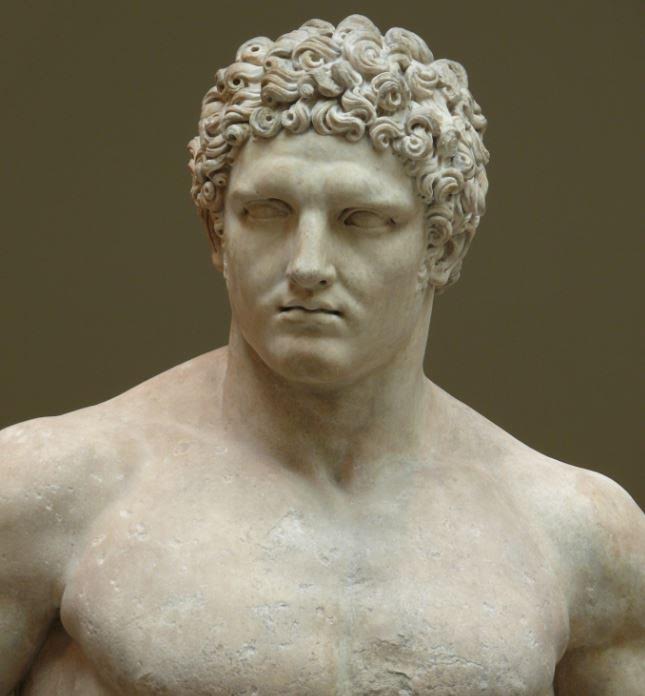

Far and away, the greatest hero of all was Herakles.

There are so many stories related to Herakles (‘Hercules’ of you were Roman) in mythology that it’s impossible to cover all of them in a simple blog post. A book would be required for that.

So, this post is going to be the first in a two-part series on the hero. There are countless triumphant deeds associated with Herakles, but for our purposes here, I’m going to cover the most famous of all – The Twelve Labours.

The Twelve Labours of Herakles have been the subject of art, sculpture and song for ages. Their portrayal decorated the ancient world from the images on vases to the metopes on the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. In our modern age, we’ve seen him in comics, television shows, and movies.

Aerial view Tiryns

But who was Herakles? Where did he come from?

Herakles was born in the city of Thebes. He was the son of Zeus who begat him on Alcmene, a granddaughter of Perseus and Andromeda. Zeus came to her in the guise of her mortal husband, Amphitryon, and so Herakles was born.

From the beginning, Herakles showed that he was not a ‘normal’ person. Out of jealousy, Hera, Queen of the Gods and wife of Zeus, sent two snakes to kill the baby Herakles in his cot. Herakles strangled the snakes with his bare baby hands.

When he was 18 years of age, Herakles began to really make a name for himself by slaying a lion on the slopes of Mount Cithaeron after hunting it for fifty days. During that time, he stayed with the king of Thespiae who was so impressed with the youth that he had him beget children on all fifty of his daughters.

Herakles was a man of extreme prowess, deeds, emotion and appetites.

King Creon of Thebes rewarded Herakles for helping him against his enemy, Erginus, king of the Minyans by giving him the hand of his daughter Megara, with whom the hero had several children.

This is where things sour for the young hero. After all, this is a Greek story, and tragedy is never far behind to bring even the mightiest of heroes back to Earth.

Temple of Apollo at Delphi

Hera stepped in to afflict Herakles with madness, causing him to kill his wife and children. When his sanity returned, he was overcome with grief and went to the Oracle at Delphi for advice.

The Oracle told him to go to Tyrins and serve its king, Eurystheus, for twelve years, as punishment for his brutal crime. He had to complete all tasks set for him by the king, and this is the origin of The Twelve Labours.

It’s curious that the name ‘Herakles’ means ‘Glory of Hera’, since she persecuted him so much throughout his life. Then again, perhaps as Hera is the root cause of his Labours, his triumphs reflect on her?

I – The Nemean Lion

This first labour is probably his most famous, and takes us to the ancient land of the Argolid peninsula. The lion that was terrorizing the hills about Nemea had skin that was impenetrable to weapons and so Herakles, when he faced it, choked it to death with his brute strength and then used the claws to skin it. It’s this skin, which he used as a hooded cloak, that the hero became known for in art. If you see someone with a lion’s head on their own, it’s likely Herakles, or someone trying to emulate him.

Region of Nemea

As a side note, Nemea was thereafter the site of the Nemean Games, one of the four sacred games of the ancient world, which also included the Isthmian Games, the Pythian Games, and the Olympic Games. You can read more about ancient Nemea by CLICKING HERE.

II – The Lernean Hydra

When he faced the Hydra in the Peloponnesian swamps of Lerna, it’s a good thing that Herakles brought along his nephew and companion, Iolaus. Facing the monster, he discovered that when he cut one head off, two more grew back in its place. And so, after each head was cut, Iolaus would cauterize the stump before it could grow again. When the Hydra was dead, Herakles dipped his arrows in the blood which was poison, even to Immortals. These arrows would come in useful in later episodes of the hero’s life.

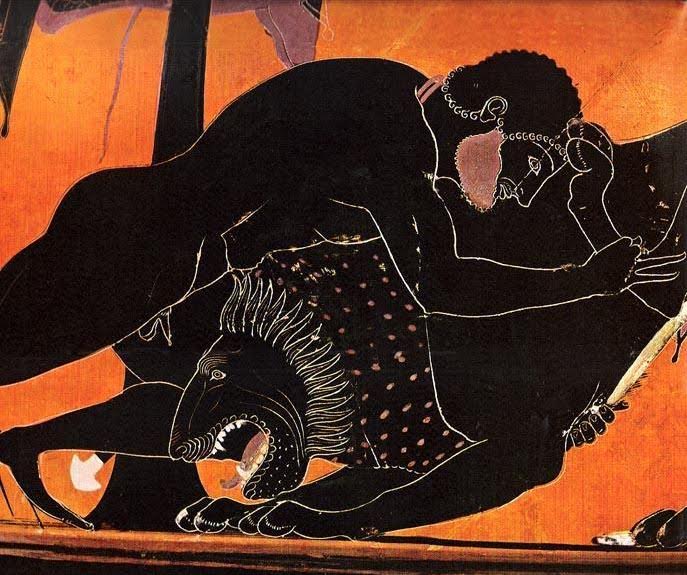

Heracles fighting the Hydra

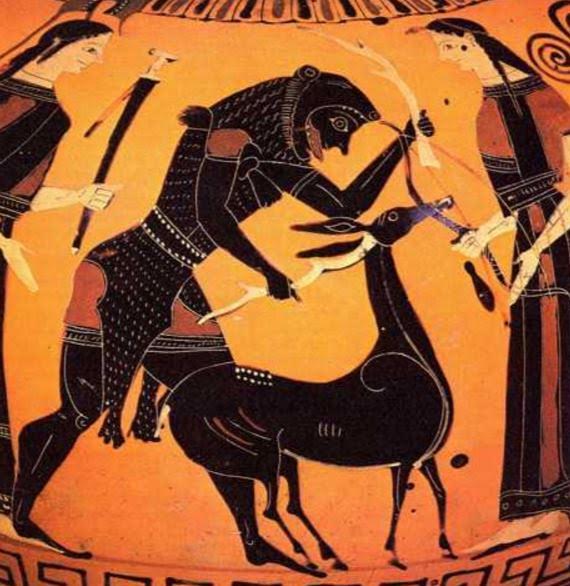

III – The Ceryneian Hind

Eurystheus, this time, thought he would set Herakles against Artemis with this third labour by telling him to capture a deer with golden horns that was sacred to the goddess. But Herakles pursued the hind for a whole year until he finally captured it and brought it before Eurystheus who, by this time, was always hiding in a jar whenever his cousin would return. The hind was allowed to go once it was brought before the king and so Herakles was able to avoid Artemis’ wrath.

The Cyreneian Hind

IV – The Erymanthian Boar

Herakles delivers the Erymanthian Boar to Eurystheus

Around Psophis, in the Arcadian region of the Peloponnese, a massive boar had been giving the locals trouble and so Herakles was sent to capture it. He did so by pursuing it through deep snow in the mountains until it was so exhausted that he was able to capture it. Such a massive specimen would have made quite a sacrificial feast!

V – The Stables of Augeas

Athena aiding Herakles to clean the Augean Stables

Augeas was the King of Elis, and he had a cattle stable that had never been mucked out, EVER! In this case, it was not a monster that terrorized the locals, but rather the monumental stench. In this very different labour, Herakles was told he had to clean out the stables. So, what did he do? What all heroes would do, he diverted the rivers Alpheius and Peneius so that they flowed through the stables and washed the titanic stink away. It’s no wonder the land thereabouts is so fertile!

VI – The Stymphalian Birds

In Stymphalia, there were flocks of man-eating birds with bronze beaks that infested the woods around the Lake of Stymphalus, again in Arcadia. Herakles was told he had to get them out. So, he scared them all from their hiding places and then shot them down with his great bow. No more birds.

Lake Stymphalos

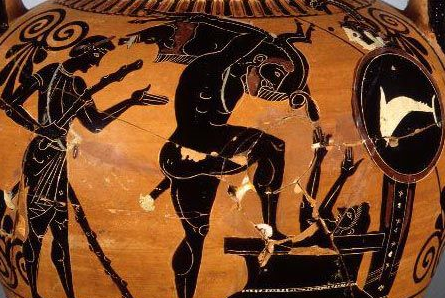

VII – The Cretan Bull

For his seventh labour, Herakles had to leave the Peloponnese for the Island of Crete to capture and bring back the Cretan Bull. This was no ordinary bull. This was the bull that Poseidon sent to Crete for King Minos to sacrifice. When Minos refused, Poseidon made his wife, Pasiphae fall in love with it and from that union was born the terror that was to become the Minotaur. The Cretan Bull rampaged all over Crete until Herakles arrived, wrestled it to the ground, and brought it back to Greece. The hero’s friend, Theseus, would come back to Crete years later to take care of the Minotaur.

The Cretan Bull

VIII – The Mares of Diomedes

Once more, Herakles was forced to deal with another group of man-eating animals. But this time they were not birds, but rather horses! The mares of Diomedes were in Thrace.

When Herakles arrived in that northern kingdom, he had a run-in with Diomedes himself and so, to tame the horses, Herakles fed them their own master. After that, the mares followed him back to Eurystheus.

The man-eating Mares of Diomedes

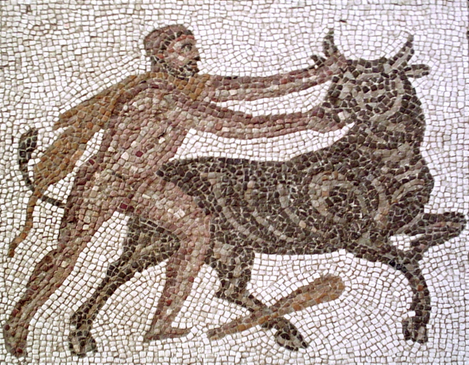

IX – The Girdle of Hippolyte

Herakles fighting the Amazons

Near the River Thermodon, just off the Black Sea, Herakles and his followers, including Theseus, went to the Amazons and their Queen, Hippolyte. The story goes that Herakles just asked this lovely daughter of Ares for her girdle, or belt, and she said ‘Yes’. Hera decided to step in and whispered to the rest of the Amazons that their queen was being abducted.

The Amazons attacked Herakles and his men who fought back, and in the bloody engagement, Hippolyte herself was killed. Herakles managed to get the girdle, but the cost of this labour was indeed heavy.

The River Thermodon

X – The Cattle of Geryon

The tenth labour is a sort of epic cattle raid. Herakles was told he had to bring back the red cattle of the three-bodied giant, Geryon, from the Island of Erytheia which was far, far to the west. This took the hero on a long journey into the Atlantic. On his way, he set up the Pillars of Hercules to mark his way.

Herakles driving off the Cattle of Geryon

But Herakles began to grow weary with the heat, and so Helios, God of the Sun, lent Herakles his great golden bowl or boat so that he could sail the rest of the way to Erytheia. Herakles succeeded in raiding the cattle and sailed in Helios’ boat back to Spain. From Spain he travelled to Greece and had many adventures on this mythic cattle drive.

There is a whole list of adventures he had on his way home, but the one I would like to highlight brings him in touch with the Romans. When Herakles arrived in Rome he came into conflict with a monster named Cacus after the beast killed some of the cattle. Herakles killed Cacus in what must have been a great battle of strength.

Temple of Hercules, Rome (Wikimedia Commons)

It’s interesting that in Rome, there are some steps leading off of the Palatine Hill called the Steps of Cacus which is where the monster is said to have lain in wait for passers-by. In the Forum Boarium, or cattle market, near the banks of the Tiber, there is a round Tholos temple dedicated to Hercules, commemorating the hero’s time in Rome.

XI – The Golden Apples of Hesperides

Hesperia was the garden of the gods, and Herakles must have been exhausted when he discovered that he had to go back to the Atlantic. Some believe Hesperia was located on the Atlantic side of the North African coast. The garden was said to be beyond the sunset, where Atlas, the Titan, was holding up the sky.

The Golden Apples of Hesperides

The labour was to pick the golden apples that were guarded by a giant snake. In some stories, Herakles asks Atlas to pick the apples for him while he holds the heavens in his stead. In others, Herakles picks the apples himself and kills the serpent.

XII – Cerberus

There is one archetype that is common to most hero stories, and that is the journey to the Underworld. And this is where Herakles must go in his final labour, to bring the three-headed hound of Hades back to Eurystheus.

Herakles and Cerberus

To get to the Underworld, Herakles gets help from the god Hermes, who travelled there regularly. Supposedly, they entered through the gate at Taenarum, in the southern Peloponnese.

There is a fascinating episode when they arrive in Hades’ realm. The shades of the dead flee from Herakles who wounds Hades himself with one of his poison arrows. The only shades who do not flee are Meleager, famed for bringing down the great Calydonian Boar, and Medusa, the Gorgon slain by Perseus.

Gate to Hades at Taenarum

Herakles drew his sword against Medusa, but Hermes told him to leave her be. But Meleager told the hero his sad tale. Herakles, inspired by Meleager, said that he would marry the sister of such a noble man. And so, the shade of Meleager named his sister, Deianaira, to be Herakles’ wife. This at the end of his long penance for killing his family. Was it a new beginning?

Hades told Herakles that he could take Cerberus if he could bring him to heel without using his weapons. In true Heraclean fashion, he wrestled the hell hound and then brought it to Eurystheus.

Afterward, Hades got his dog back.

Herakles resting after his Labours

The Labours of Herakles are not just adventure stories. They are stories of atonement, of courage, of strength of mind and body. Over and over, the hero is taken to extremes until he attains his final triumph, and his debt is paid.

But this is a Greek story. There is no celebration. For laurels dry out on the brow of even the greatest of heroes.

There is much more to Herakles’ story. I don’t think I’ll ever tire of these tales.

Next week, in the second part of this series, we are going to be looking at the tragedy of Herakles.

Thank you for reading, and until then, stay Strong!

The World of Heart of Fire – Part X – A Novel of the Ancient Olympics

This is the final post in The World of Heart of Fire blog series.

I sincerely hope you have enjoyed it.

Writing Heart of Fire has been a tremendous journey into the world of Ancient Greece. Yes, I am an historian and I already knew much of the material, but I still learned a great deal.

The intense, and in-depth, research, some of which you have read about in this ten-part blog series, made me excited to get stuck in every day. A lot of people, after an intensive struggle to write a paper or book, are fed up with their subject afterward, but that is not the case for me.

In writing this story, and meeting the historical characters of Kyniska, Xenophon, Agesilaus, and Plato, in closely studying their world, I have fallen even more in love with the ancient world. I developed an even deeper appreciation of it than I had before.

In creating the character of Stefanos of Argos, and watching him develop of his own accord as the story progressed (yes, that does happen!), I felt that I was able to understand the nuances of Ancient Greece, and to feel a deeper connection to the past that goes beyond the cerebral or academic.

I’ve come to realized that in some ways we are very different from the ancient Greeks. However, it seems to me that there are more ways in which we have a lot in common.

Sport and the ancient Olympics are the perfect example of this.

We all toil at something, every day of our lives. Few of us achieve glory in our chosen pursuits, but those who do, those who dedicate themselves to a skill, who sacrifice everything else in order to reach such heights of glory, it is they who are set apart.

In writing, and finishing, Heart of Fire, I certainly feel that I have toiled as hard as I could in this endeavour. My ponos has indeed been great.

There is another Ancient Greek idea that applies here, that comes after the great effort that effects victory. It is called Mochthos.

Mochthos is the ancient word for ‘relief from exertion’.

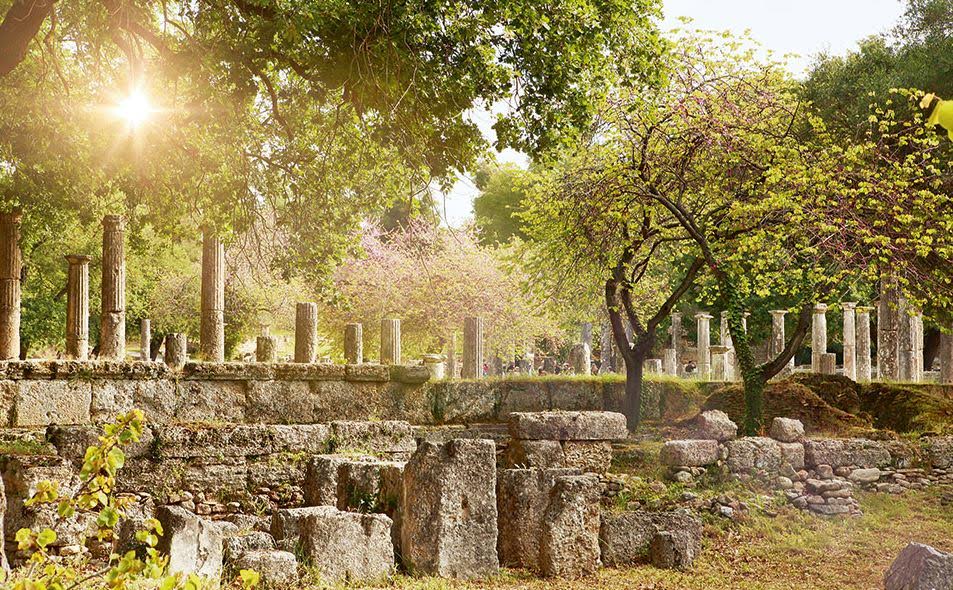

Athens 2004 – Mochthos

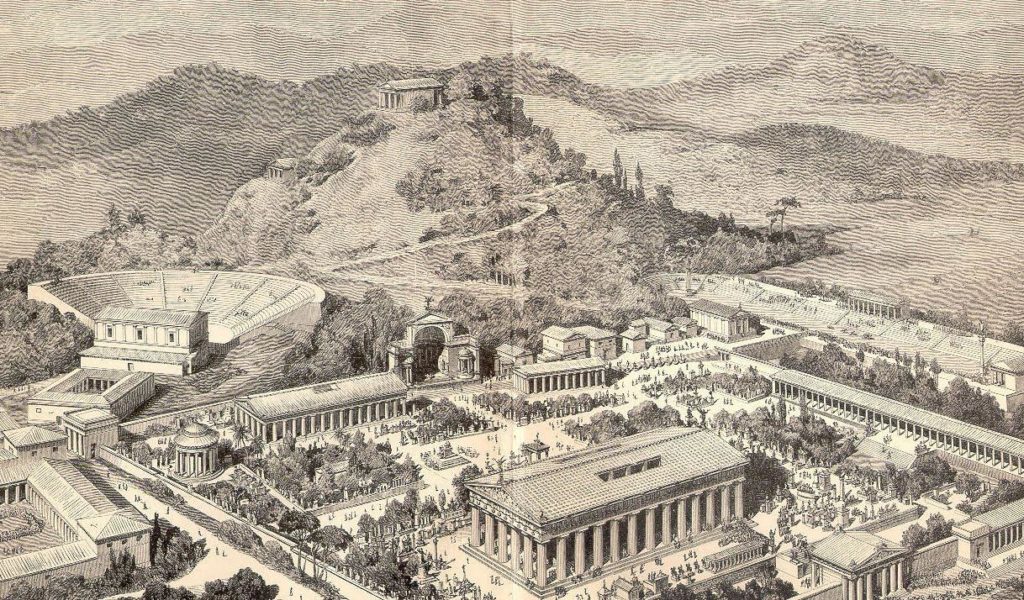

My moment of mochthos will come when I return soon to ancient Olympia. I have been there many times before, but this time will be different, for I will see it in a new light – the stadium, the ruins of the palaestra and gymnasium, the Altis, and the temples of Zeus and Hera… all of it.

For me, Olympia has exploded with life.

When I next walk the sacred grounds of the Altis, I’ll be thinking about the Olympians who competed this summer and in the years to come.

They deserve our thoughts, for to reach the heights of prowess that they do to get to the Games, they have indeed sacrificed.

Athens 2004

I always feel a thrill when I see modern Olympians on the podium, see them experience the fruit of their toils, their many sacrifices.

It is possible that they may have been shunned by loved ones or friends for their intense dedication and focus. It can be a supremely lonely experience to pursue your dreams.

Whatever their situation, Olympic competitors deserve our respect, and just as in Ancient Greece, their country of origin should matter little to us.

Yes, we count the medals for our respective countries, but what really matters is that each man and woman at the Games has likely been to hell and back to get there.

Athens 2004 proud winner

When I see the victors on the podium, when I witness the agony and the ecstasy of Olympic competition, I can honestly say that I have tears in my eyes.

Perhaps you do too? Perhaps the ancient Greeks did as well, for in each individual victor, they knew they were witnessing the Gods’ grace.

It’s been so for thousands of years, and it all started with a single footrace.

It is humbling and inspiring to think about.

Heart of Fire – A Novel of the Ancient Olympics is out now, and I hope that I have done justice to the ancient Games and the athletes whose images graced the Altis in ages past.

A Mercenary… A Spartan Princess… And Olympic Glory…

When Stefanos, an Argive mercenary, returns home from the wars raging across the Greek world, his life’s path is changed by his dying father’s last wish – that he win in the Olympic Games.

As Stefanos sets out on a road to redemption to atone for the life of violence he has led, his life is turned upside down by Kyniska, a Spartan princess destined to make Olympic history.

In a world of prejudice and hate, can the two lovers from enemy city-states gain the Gods’ favour and claim Olympic immortality? Or are they destined for humiliation and defeat?

Remember… There can be no victory without sacrifice.

Be sure to keep an eye out for some short videos I will be shooting at ancient Olympia in the places where Heart of Fire takes place. I’m excited to share this wonderful story with you!

Thank you for reading, and whatever your own noble toils, may the Gods smile on you!

If you missed any of the posts on the ancient Olympic Games, CLICK HERE to read the full, ten-part blog series of The World of Heart of Fire!

If Heart of Fire – A Novel of the Ancient Olympics sounds like a story you enjoy, you can download the e-book or get the paperback from Amazon, Kobo, Create Space and Apple iBooks/iTunes. Just CLICK HERE.

The World of Heart of Fire – Part III – Athletics and War in Ancient Greece

Nearly all the sports practised nowadays are competitive. You play to win, and the game has little meaning unless you do your utmost to win… At the international level sport is frankly mimic warfare… Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war minus the shooting. (from George Orwell’s The Sporting Spirit, Tribune, December 1945)

This is from an oft-quoted work by George Orwell after a particularly violent football match in 1945 between England and Russia.

With our modern sensibilities toward sportsmanship and fair play, many of us would agree with George Orwell’s sense of disgust at the violence that had permeated sport. Click here to read the full piece. That said, today, with the pervasiveness of violence in the media, including sports coverage, I think our modern sensitivities toward sport have taken a few steps backward.

However, when it comes to the ancient Olympics, the quote above rings true.

In this third part of The World of Heart of Fire, we are going to look briefly at the relationship between athletics and war in Ancient Greece, and how the political atmosphere at the time made for some brutal competition on, and off the battlefield.

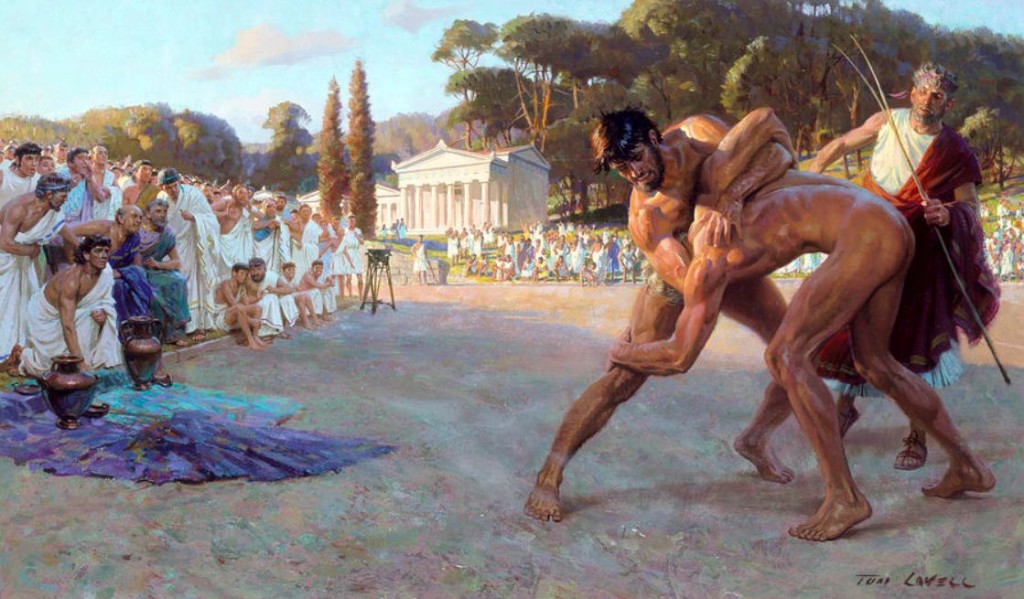

Artist re-creation of ancient wrestling

If you read the full piece by Orwell, you will see that he mentions a decline in the importance of athletics from the Roman period onward.

In the Greek world, however, athletic training was central to a young man’s education, and in Sparta, to a woman’s as well.

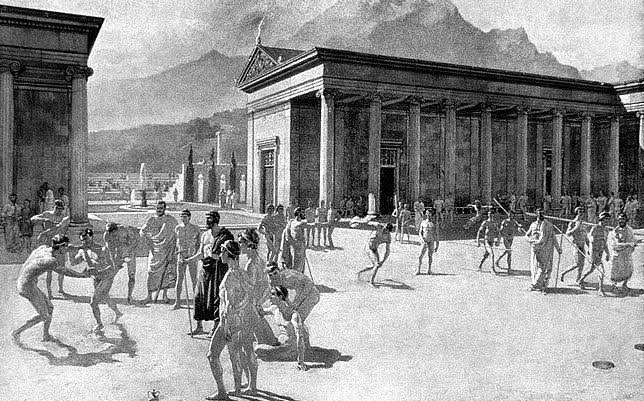

Before we delve deeper into the relationship between athletics and war, we should take a brief look at the athletic institutions that were crucial to a young man’s education – the Gymnasium, and the Palaestra.

In Ancient Greece, one of the key markers of a civilized city was the presence of a gymnasium. Now, this is not the sort of gym where today, young kids play dodge ball, or where people go to pump some iron and then head home. There was much more to the ancient gymnasium than that.

A gymnasium was a public institution for young men over eighteen years of age, a place where they went, not only to train for the public games or sporting events, but where they also trained for life.

Artist impression of a gymnasium

In addition to sports training, there were also lectures on philosophy, art, music, and literature. Gymnasia were really schools for a society’s future leading citizens, especially in a democracy.

According to Pausanias, it was Theseus who first regulated gymnasia in Athens. Later, the great lawmaker, Solon, created a set of laws to govern gymnasia.

A gymnasium was a large facility that included a palaestra, baths, a stadium for competition, and porticoes where lectures were given by philosophers and discussions could be had, especially in inclement weather.

The great gymnasium of Olympia is one of the most famous, and the remains can be seen to this day.

Remains of Olympia Gymnasium

At Athens, there were three famous gymnasia – The Academy (founded by Plato), the Lyceum (founded by Aristotle), and the Cynosarges (founded by Antisthenes) where the cynic school was said to have begun.

These are some pretty big names, and their involvement and founding of these institutions only speaks to the importance of gymnasia in Greek society.

The other important institution is the palaestra.

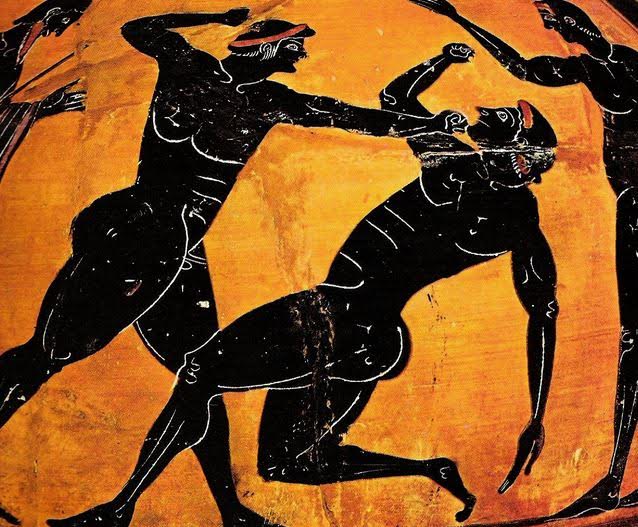

This was a wrestling school. It could also be considered a martial arts school, for it was a place where not only wrestling was taught, but also boxing and pankration.

A gymnasium always included a palaestra, but a palaestra could be a stand-alone entity, as well as privately owned.

Olympia is one of the best examples of a palaestra.

Olympia Palaestra

This was like an athletic club, a place where men could train for combat and competition, but also socialize and bathe.

A palaestra was typically a rectangular or square building with a colonnade surrounding a sandy area where fighting took place called a skamma. There were adjoining rooms off of the main courtyard that could be used for socializing, games, and bathing, as well as storage rooms where oil and dust were stored.

While lectures could take place at a palaestra, they were mainly focussed on the physical strengthening, skill, and improvement of young men.

The importance and prestige of belonging to a palaestra cannot be overstated when it comes to Ancient Greek society. So much so, that there was a term for those who were poor, those who were without a palaestra – apalaistroi.

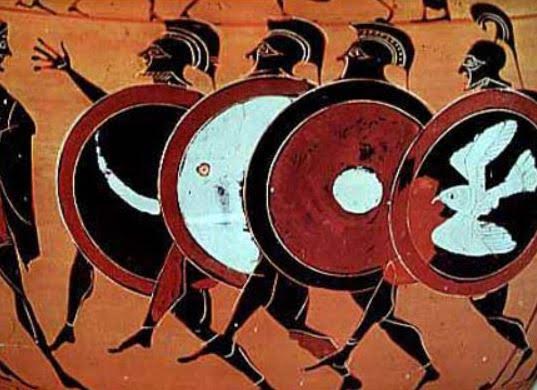

Re-enactors dressed as hoplites

It is important that we not kid ourselves here. Athletics and war were very closely related in Ancient Greece, and any man who was expected to wield a hoplon and doru in the shield wall of a phalanx was likely someone who trained at either the gymnasium or palaestra.

Sport and athletic competition was indeed ‘war without the shooting’ as Orwell so aptly put it.

In Greek society, words like arete (‘manly excellence’), andreia (‘manliness’), eumorphia (‘in good shape’), promachoi (‘fighters in the front line’), and philonikia (‘love of winning’) were deeply ingrained in a young man’s psyche, in his training to be an effective citizen for his city-state.

These are ideas that I have tried to weave into the story of Heart of Fire, for they are so very important to understanding this world that, let’s face it, despite the similarities, is so very different from our own.

Plato’s Academy

But now we must look at the politics of the time in which Heart of Fire takes place, for at this time, when the entire Greek world was drowning in fire and blood, all of the training young Greek men would have received at the gymnasium or palaestra would be turned to combat on the fields of Ares.

To my mind, the Peloponnesian War is a supremely depressing episode in Greek history. After the glories of the Persian Wars, when the Greeks united to stand against a common foe, it is heart-breaking to see how they tossed the glory of their fathers to the winds.

Marathon, Thermopylae, Salamis, and Plataea were no more…

The Pass at Thermopylae

Despite the efforts of some philosophers such as Isocrates of Athens (436-338 B.C.) to persuade the city-states to unite and focus on Persia once more, the Greeks turned on each other.

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.) was mainly a conflict between the two major city-states of the day, Athens and Sparta, and their respective allies.

This war saw the ‘death’ of Athens and, some might say, Democracy. It saw Sparta ally itself with the Persians against her fellow Greeks, and it saw Greece’s Golden Age turn to dust.

Mourning Athena

After ten years of heavy losses on both sides of the conflict, Athens and Sparta brokered a peace called the Peace of Nicias (421 B.C.), named after the Athenian general who led talks. This peace declared a peace treaty between Athens and Sparta for fifty years, with temples all over Greece being open to all again, granting autonomy to Delphi, and the return of territories and POWs.

Sadly, this peace broke down almost at once. In 418, Sparta was victorious over Athens, Argos, and other pro-democrats at Mantinea. Then, in 417 B.C., Sparta attacked Argos at Hysiae.

In 415 B.C. Athens attacked the Spartan ally of Melos and committed major atrocities there before planning their ill-fated Sicilian Expedition against the Spartan ally of Syracuse. What followed was a massive Athenian defeat with the loss of nearly a generation of Athenian youth, and the instalment of the men known as the 30 Tyrants (404-403 B.C.)

The 30 Tyrants were a pro-Spartan oligarchy installed in Athens after the latter’s defeat in the Peloponnesian War in 404 B.C. They were in power for thirteen months, a time in which the thirty instituted a reign of terror in which nearly five percent of Athens’ population was killed and their property taken.

Democracy went into exile, and the democrats in exile grew stronger and more determined the more brutal the 30 Tyrants became.

The Greek world was bitter, battered, and bruised.

Map of movements during the Peloponnesian War

This was a time of retribution, and with the defeat of the 30 Tyrants by the pro-Democratic forces led by the Athenian general, Thrasybulos, Athens seemed to forget her ideals and former glories in some ways, threatening to kill all those who sought to destroy their Democracy.

This is the period just prior to when Heart of Fire begins, a period that saw to the public trial and death of one of Ancient Greece’s most famous and influential people – Socrates.

This is also the time when, after the battles had slowed, and warriors now found themselves idle, 10,000 Greek mercenaries joined the losing side in the Persian civil war and found themselves marching back to Greece while harried by Persian forces who wanted nothing more than to slaughter them.

This last event is recounted in the Anabasis of the exiled Athenian warrior, Xenophon. It is known as the March of the 10,000.

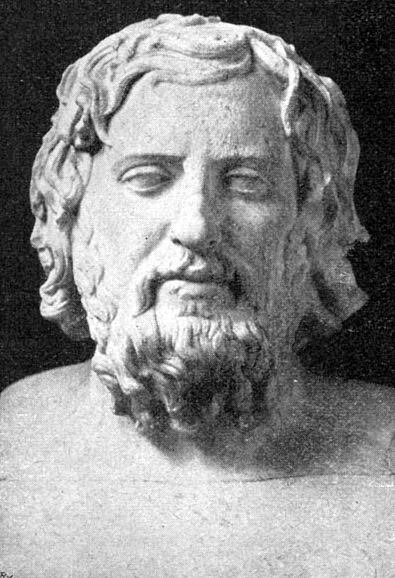

Xenophon, son of Gryllus

What did all this blood, battle and hardship have to do with athletics?

Everything.

In Ancient Greece, the lessons young men learned in the gymnasium, or on the sand of the palaestra, were implemented on the battlefield.

Athletics training really was ‘war without the shooting’, and athletic events such as sprinting, jumping, wrestling, boxing, javelin, and running in full armour, served non only to make men better citizens, but also better, more effective warriors for their city-state.

And with the state of the Greek world at the time Heart of Fire takes place in 396 B.C., there were a lot of men fresh from the battlefield who had come to compete in the Olympic Games after the Peloponnesian War.

The Sacred Truce was instituted once more, but one can imagine the tension at Olympia during those games, after all that had happened in the last forty years.

The Games of 396 B.C. were about more than proving oneself in the eyes of the gods and honouring the city-state. They were about winning at all costs.

Greek hoplites in battle

Sadly, after those Games, yet another war broke out, known as the Corinthian War (395-387 B.C.) in which Sparta and her oligarchical allies waged war on the Democratic cities of Athens, Thebes, Corinth and Argos.

The cycle of sport and war seemed to continue.

I’m very happy to announce that Heart of Fire – A Novel of the Ancient Olympics is now out in e-book and paperback from Amazon, Create Space, Apple iTunes/iBooks, and Kobo.

As ever, thank you for reading, and I hope you’ll join us next week for Part IV of The World of Heart of Fire.

The World of Heart of Fire – Part II – 776 B.C. – The Historical Beginnings of the Olympic Games

In the last post we looked at the mythological origins of the Olympic Games.

In part two, we are going to take a brief look at the Olympic Games as history remembers them, but that too is a hazy undertaking.

Most historians agree that the first recorded Olympic Games took place in 776 B.C. and ran for almost twelve centuries until they were banished as a pagan practice by the Christian, Roman emperor, Theodosius I in c. A.D. 394.

When the games began in the eighth century, the city-states of Greece were on the rise, and so it was inevitable that politics would enter into the Games early on. Olympia was actually fought over, and an example of this was the ongoing argument between Elis and Pisa, an argument in which Sparta eventually became involved.

Control of Olympia passed back and forth between Elis and Pisa, but the Eleans eventually won out. Nevertheless, the Olympic Games were a place where city-states met and declared their strength, their grievances, and their alliances.

Artist impression of Ancient Olympia

Despite the occasional rancour and politicizing of the Games, the Olympiad remained a sincere religious ritual overseen by the Gods themselves and in honour of Olympian Zeus.

There were other ‘crown games’, as they were known. These included the Pythian Games in honour of Apollo at Delphi, the Nemean Games in at Nemea, and the Isthmian Games in honour of Poseidon at ancient Isthmia, near Corinth.

Many men competed in all of the crown games, but the Olympiad was the greatest and most revered of these games. A victory there made a man all but immortal.

Modern IOC symbol for Olympic Truce – the tradition continues!

When the Olympic Games were declared, the entire Greek world was supposed to come to a standstill during a peace known as the Sacred Truce, or Ekecheiria, which means a ‘laying down of arms.’

To violate the peace of the Sacred or Olympic Truce, was to dishonour the Gods and risk their anger.

This would have been difficult during a time such as the Peloponnesian War when the city states were at each other’s throats and tearing their world apart. It is no surprise that Olympic competition could turn deadly, but more on that later.

Greek hoplite battle

Only freeborn, Greek men were permitted to compete in the Olympiad, and at first, it was mainly men from the Peloponnese, as evidenced by the high number of Arkadians on the early victor lists.

Women, as mentioned in the previous post, were only permitted within the sanctuary during the Games of Hera, the Heraia, the first officially recorded one of which took place in the sixth century B.C.

The banishment of women from the Games, it is said, began around 720 B.C. when men began to compete in the nude rather than loin cloths.

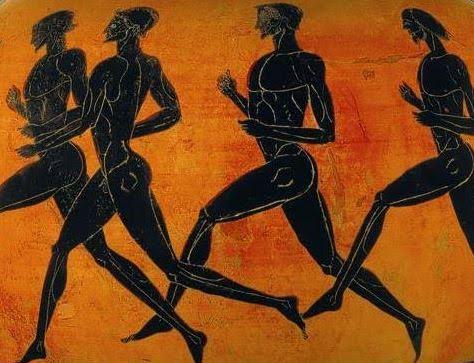

Initially, the Olympic Games took place over a single day, and the only event was the stade race. This was a sprint of about 200 meters, which was the length of the stadium at Olympia, said to have been measured after the steps of Herakles himself.

So, the original Olympic event was the two-hundred meter sprint!

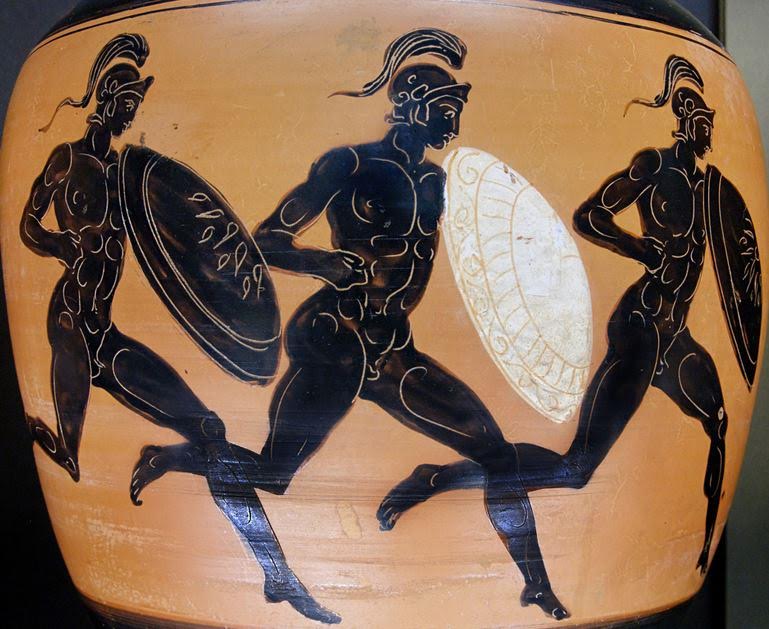

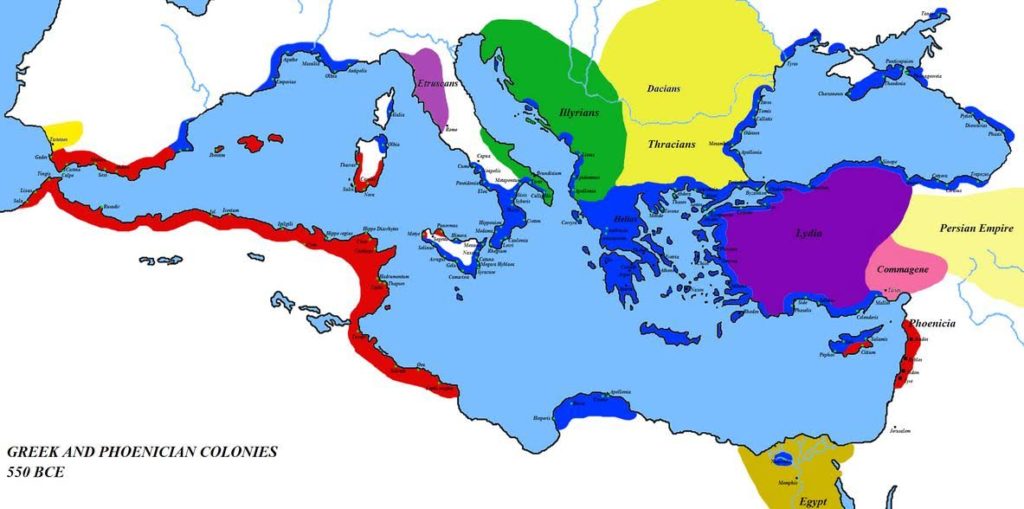

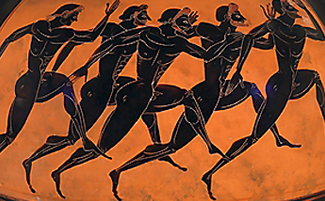

Ancient greek runners

Over time, as Greek colonies began to spread across the Mediterranean world, and the Games grew in popularity, Greeks from outside of the Peloponnese, much farther afield, began to travel to Olympia to compete. More days, and more events were added to the games until we arrive at the year in which Heart of Fire takes place – 396 B.C.

This was a brutal period in Greece’s history. All of the city states were bitter and reeling from the Peloponnesian War (c. 431-404 B.C.), and they were still having at each other, even in the midst of a supposed peace, called the Peace of Nicias.

Sparta and Athens were at the forefront of the aggressions, as were Thebes, Corinth, Argos and others. The Olympiad of 396 B.C. has certainly been an interesting and complex period to write about. We’ll explore the politics of the period more in the next post.

Greek Colonies of Mediterranean (in blue)

By the time of the 396 B.C. Olympiad, the Games were five days long, rather than the original one, and had many more events. Here is the most agreed-upon order of events:

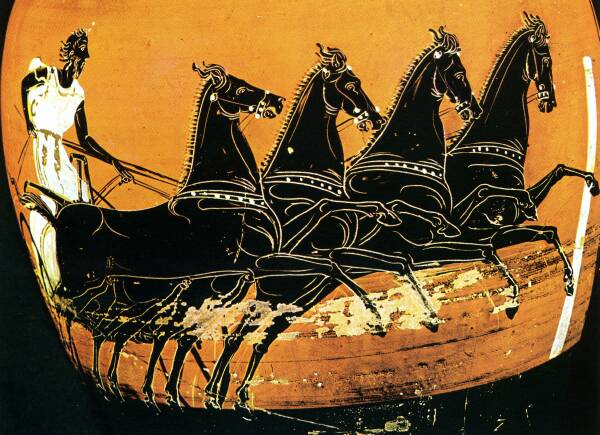

Day 1 – This was the day for the equestrian events, including bareback horse races, the two-horse chariot race, the Synoris, and the marquee event, the Tethrippon, or four-horse chariot race.

Chariot racing in the ancient Olympics

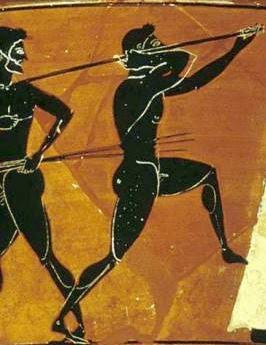

Day 2 – This was the day for the Pentathlon which was an event that tested the best, all-around, warriors, It included a stade race of 200 meters, standing long jump with the use of weights called halteres, the discus, the javelin or akontismos where throws could soar over 100 meters, and lastly wrestling.

Javelin thrower

Day 3 – The third day was reserved for the foot races. By 396 B.C., these included the stade race (200 meters), the diaulos (400 meters), and the dolichos (a long distance race that could be anywhere from 2,400 to 5000 meters). About twenty runners competed at a time, having chosen lots to determine their heat. They stood on the starting line of the stadium and waited until the judge yelled “Apite!”

Runners

Day 4 – This was the day of the fighting events, and make no mistake, these were brutal. Men died. These included the wrestling, boxing, and the no-holds-barred Pankration.

Pankration

Day 5 – The last event of the ancient Olympics is one that has faded away into the pages of history, but which has its origin, some believe, in the foundation myth of Daktylos Herakles, mentioned before, and the armoured Daktyloi who were charged with protecting the baby Zeus on Mt. Ida in Crete in the age of Kronos. This final event was a hoplite race, a sprint for men dressed in full hoplite armour and each running with one the twenty sacred shields that were stored in the Temple of Hera at Olympia. This was known as the Hoplitodromos, and in Heart of Fire, we get to experience this unique and almost forgotten Olympic event.

The Hoplite Race

So, there you have it! Those are the events of the ancient Olympic Games. Much has changed, though it is fantastic to think that some of the Olympic events we have today started so very long ago.

But sport was only a part of the ancient Olympics. It’s important to remember that overall, this was a major religious ritual that commanded respect from all Greeks, despite the politics of the day.

In Part III of The World of Heart of Fire, we are going to look at the importance of athletics in Ancient Greece and delve a bit more into the political atmosphere of the year 396 B.C.

Thank you for reading, and see you next week.

The World of Heart of Fire – Part I – Ancient Origins: The Mythological Beginnings of the Olympic Games

Greetings readers and history-lovers!

I’m pleased to welcome you to the very first post in this new blog series about the ancient Olympics and Eagles and Dragons Publishing’s newest book, Heart of Fire – A Novel of the Ancient Olympics.

Over the next ten weeks or so, we will be looking at all aspects of the Olympic Games from their foundation and religious ceremonies, to ancient athletics, individual sports, and the actual site of ancient Olympia as it relates to the Olympiad of 396 B.C. when Heart of Fire takes place.

In this first post, we are looking at the mythological beginnings of the Olympic Games as given in three traditions.

Battle between the Gods and the Titans

There are three myths related to the foundation of the Olympic Games, and the first begins with the war between the Gods and the Titans.

Ancient Olympia is dominated by an ancient hill known as the Hill of Kronos. Now, Kronos, a Titan, as we know, was the father of Zeus who, along with his siblings, waged war on Kronos and the Titans.

One of the legends associated with Olympia is that it was where Zeus wrestled with, and defeated, his titanic father. Some believe the games were established to commemorate that victory, and that the site at the base of the Hill of Kronos was where Zeus himself wrestled and defeated Kronos.

Hill of Kronos overlooking sanctuary of Olympia

Another tradition around the Olympic Games is that they were founded by Herakles in thanks to his father, Zeus, for granting him victory in war.

The great epinikion poet, Pindar, speaks of this in his Olympian Ode #10:

With the help of a god, one man can sharpen another who is born for excellence, and encourage him to tremendous achievement. Without toil only a few have attained joy, a light of life above all labors. The laws of Zeus urge me to sing of that extraordinary contest-place which Heracles founded by the ancient tomb of Pelops with its six altars, after he killed Cteatus, the flawless son of Poseidon and Eurytus too, with a will to exact from the unwilling Augeas, strong and violent, the wages for his menial labor…

…But the brave son of Zeus gathered the entire army and all the spoils together in Pisa and measured out a sacred precinct for his supreme father. He enclosed the Altis all around and marked it off in the open, and he made the encircling area a resting-place for feasting, honoring the stream of the Alpheus along with the twelve ruling gods. And he called it the Hill of Cronus; it had been nameless before, while Oenomaus was king, and it was covered with wet snow. But in this rite of first birth the Fates stood close by, and the one who alone puts genuine truth to the test, Time. Time moved forward and told the clear and precise story, how Heracles divided the gifts of war and sacrificed the finest of them, and how he established the four years’ festival with the first Olympic Games and its victories.

We will hear more about the Theban poet, Pindar, later throughout this blog series. For now, this small part of the ode mentions several things we should note. There is reference to Pelops whose tumulus was located in the middle of the Olympic sanctuary and whose story is big part of Heart of Fire.

Pindar also references one of Herakles’ labours which was to clean out the stables of King Augeas. More importantly, Pindar paints us a picture of the Olympic sanctuary and the Altis, which was marked out by Herakles as a place for rest and feasting at the base of the Hill of Kronos, and where every four years the Olympic festival was held.

At the first Olympics begun by Herakles, it is said that the gods themselves competed, with Apollo defeating Hermes in a foot race, and also defeating Ares, the God of War, in boxing.

The God Hermes running

But there is another tradition about Herakles…a different Herakles.

There were two Herakles?

Apparently so. The second was not the son of Zeus and Alcmene. He was known as Daktylos Herakles and it seems that the tradition around this second Herakles could be even older.

In the age of Kronos, when Zeus was a baby, Kronos was devouring his children (that’s a whole other story!). To keep the baby Zeus safe, his mother Rhea gave her son into the care of five Daktyloi, daimones whose duty it was to protect Zeus in a cave on Mt. Ida in Crete. To drown out the cries of the baby, the danced wildly and clashed their spears and shields together so that Kronos would not find Zeus.

Supposely, Daktylos Herakles was the leader of the five Daktyloi, who established the Olympic Games in the age of Kronos (Cronus). One of the oldest Olympic events, as we shall see in a later post, was the hoplite race in armour, and this aligns with the use of spears and shields by the five Daktyloi who were often pictured as armoured youths.

Baby Zeus and Idaean Daktyloi dancing and making noise to protect the infant Zeus

Pausanias, in his Description of Greece, touches on the Daktyloi here:

As for the Olympic Games, the most learned antiquarians of Elis say that Kronos was the first king of heaven, and that in his honour a temple was built in Olympia by the man of that age, who were named the Golden Race. When Zeus was born, Rhea entrusted the guardianship of her son to the Daktyloi of Ida, who are the same as those called Kouretes (Curetes). They came from Kretan (Cretan) Ida–Herakles (Heracles), Paionaios (Paeonaeus), Epimedes, Iasios and Idas. Herakles being the eldest, matched his brothers, as a game, in a running-race, and crowned the winner with a branch of wild olive, of which they had such a copious supply that they slept on heaps of its leaves while still green. It is said to have been introduced into Greece by Herakles from the land of the Hyperboreans, men living beyond the home of Boreas . . . Herakles of Ida, therefore, has the reputation of being the first to have held, on the occasion I mentioned, the games, and to have called them Oympiakos (the Olympics). So he established the custom of holding them every fifth year, because he and his brothers were five in number.

Now some say that Zeus wrestled here with Kronos himself for the throne, while others say that he held the games in honour of his victory over Kronos. The record of victors include Apollon, who outran Hermes and beat Ares at boxing . . .

(Pausanias, Description of Greece 5. 7. 6 – 10)

Over time, the association of Daktylos Herakles with the Games became merged with the more famous Herakles, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, whose Twelve Labours were illustrated on the frieze of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia.

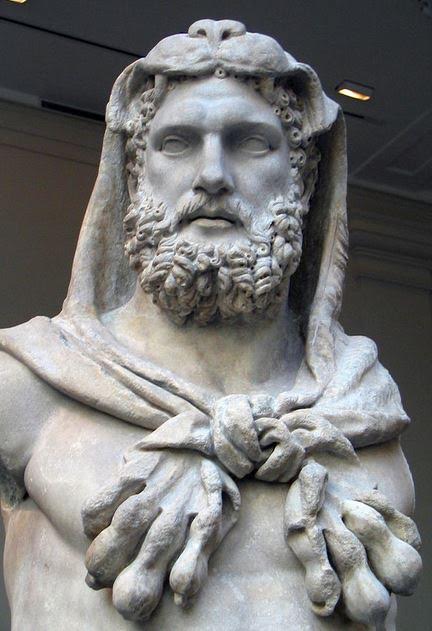

Herakles

So much for Daktylos Herakles.

There is a final myth associated with the foundation of the Olympic Games, and that is the legendary chariot race between Oinomaus, son of Ares, king of Pisa and father of Hippodameia, and the hero, Pelops, after whom the Peloponnese is named.

King Oinomaus was supposedly a cruel ‘wine-loving’ man and father who continuously slew all the suitors for his daughter Hippodameia’s hand in a chariot race from Olympia to Argos.

When Pelops, a prince from Lydia arrived to take up the challenge with the aid of some divine horses given him by Poseidon, Oinomaus’ reign of terror came to an end, and Pelops and Hippodameia were married.

Pelops and Hippodameia

Now I have really simplified the story here because we will look at it more closely in a later post. However, this particular foundation myth points to the Games as an event to commemorate Pelops’ victory.

In tandem with the Olympic Games, said to be established by Pelops in this instance, Hippodameia was said to have established the Games of Hera, the Heraia, in thanks to the goddess for granting the victory as well. You can read more about the Heraia HERE.

The chariot race was the marquee event at the Olympic Games, and central to the story of Heart of Fire, as is the tale of Pelops and Hippodameia.

There was much testament to this particular foundation myth around the Altis of Olympia as well. One of the pediments from the temple of Zeus shows Oinomaus and Pelops with their chariots, on either side of Zeus, getting ready to race.

East pediment of the temple of Zeus at Olympia showing Zeus between Oinomaus and Pelops, just before their race