ancient Greece

Harvest Time – From Eleusis to Avalon

The Autumn Equinox has come and gone, and a giant ‘Blood Moon’ made its round of the earth. From the photos I’ve seen, it was spectacular.

Harvest time is here.

However, in the city, it’s a bit difficult to feel a connection to harvest, our rural roots having been eclipsed long ago by fast, urban living.

In a small effort to reconnect with the earth and our western ancestors who were bound to it, I thought I’d mention a couple of traditions around what has been, for thousands of years, an extremely sacred time of year.

Of course, this is the time of year for Thanksgiving (earlier in Canada than in the USA) when we sit around the table en-famille and stuff ourselves like the turkeys that grace our tables. And wine, oh yes, and lots of it for the oenophiles among us.

But where does all this come from? Not the pilgrims, I can tell you that.

Apart from this being the time of year when summer gives way to fall, when the length of days is equal to that of nights, this time of year is when crops were harvested and preparations made for the coming winter.

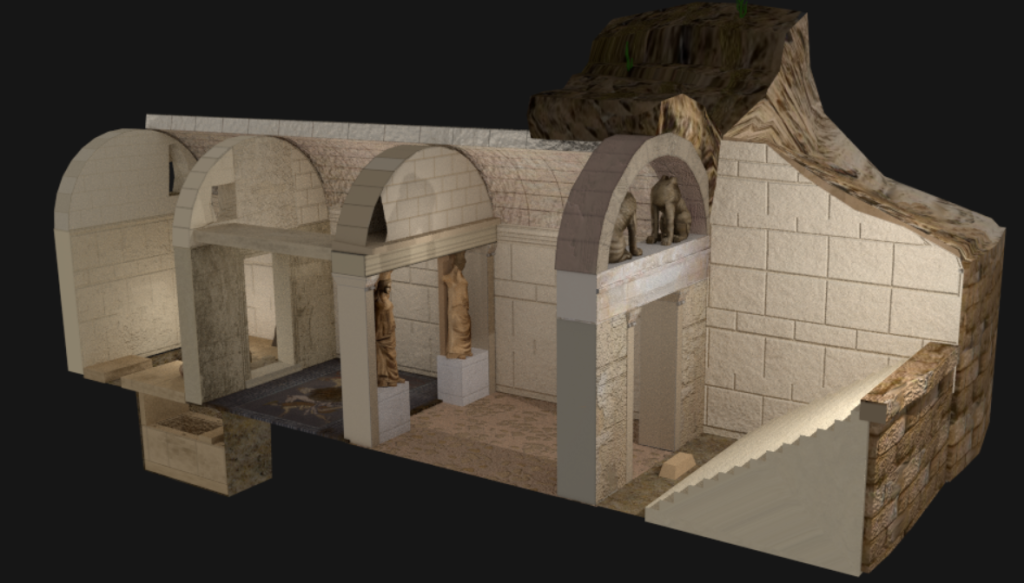

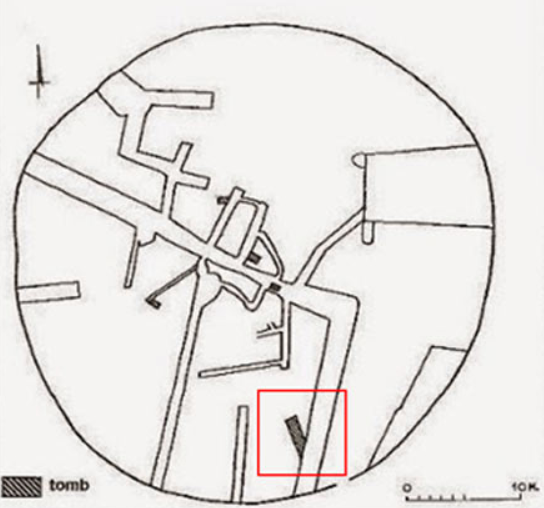

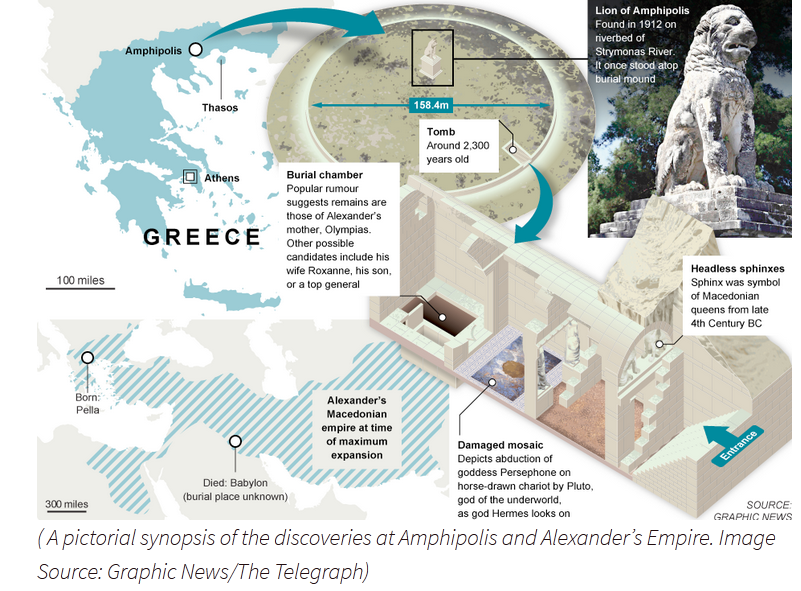

In ancient Greece it was the month of Beodromion and the festival Apollo, and the time for one of the most sacred rites: The Eleusinian Mysteries. The Mysteries were of course, in honour of the Goddess Demeter who was associated with crops, fertility, harvest and the protection of marriage. The Mysteries also honoured Persephone, Demeter’s daughter who would go to spend half the year in the Underworld with Hades. The time of harvest is associated with the death of agriculture and Persephone’s time away from her mother, the time Demeter would weep, wintertime.

“Queenly Demeter, bringer of seasons and giver of

good gifts, what god of heaven or what mortal man has rapt away

Persephone and pierced with sorrow your dear heart? For I heard

her voice, yet saw not with my eyes who it was. But I tell you

truly and shortly all I know…

(from Hesiod’s Hymn to Demeter – Hecate to Demeter)

…But grief yet more terrible and savage came into the

heart of Demeter, and thereafter she was so angered with the

dark-clouded Son of Cronos that she avoided the gathering of the

gods and high Olympus, and went to the towns and rich fields of

men, disfiguring her form a long while.”

(from Hesiod’s Hymn to Demeter)

The cult of Demeter and Persephone existed for over one thousand years and Eleusis, one of the most sacred places of ancient Greece, was where the highly secretive ceremonies would take place in September and October. Sparse details about the ceremonies include bathing in the sea, sacrificing a piglet (not a turkey!), various sacred, secret objects, and a procession from Athens to Eleusis.

The site of Eleusis is itself an amazing archaeological site that is well worth the visit if ever you have the opportunity. Apart from the vast complex of temples, and other remains, you can see the cave where Persephone supposedly descended into the Underworld, a door to Hades’ realm. Facing the dark entrance is a well, known as the “Tears of Demeter”, thus named because of the goddess’ weeping in that spot. It’s a very moving place.

Let us not dwell too long in ancient Greece however, for our Celtic ancestors in Europe also revered this time of year. To the Celts, harvest time was also known as Alban Elfed (Welsh for ‘Light of Autumn’), and the Feast of Avalon (Feast of Apples) among other names.

To the Celts, this was the time of year when the acorns fell from the sacred oaks and the last sheaf of wheat was cut by a young maiden. It was a time of reverence and thanks for the Earth’s bounty, a time to harvest once more, and to slaughter animals before the onset of winter. An offering of apples would often be placed on burials to symbolize rebirth, hence the Feast of Avalon, Avalon of course being the ‘land of apples’.

Harvest time, to the Celts, also preceded the sacred festival of Samhain which marked the end of the light of summer and the beginning of winter’s dark. Again, the cycle of light and dark, birth and death is an ever present arch-type, a cycle of which our ancestors were keenly aware and for which they had a deep respect.

So, as we sit to our laden tables this autumn, perhaps we should tip a bit of wine to the goddess who wept for her daughter’s departure into darkness, and for the end of light. When the harvest moon shines down on us in all its luminescence where we live in a world of concrete floors and steel girders, think of our forest and field-dwelling ancestors. They looked up at that same moon for ages from the dark circles of their sacred groves, and gave thanks for all they had.

Thank you for reading.

The Art of Greek Ceramics – A Look at ‘Ceramotechnica Xipolias’

I have a weakness for souvenirs.

Whenever I travel, I like to purchase something that reminds me of my evanescent days abroad. I don’t mean tacky, mass-produced rubbish that wasn’t even made in the country I visited.

I like to purchase something that is made locally, by local artists, with care and attention to detail.

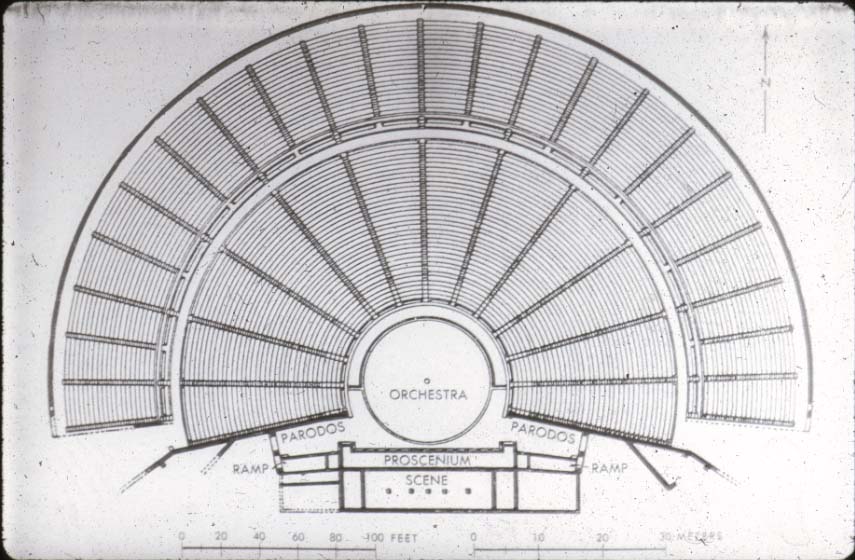

One of the places I visited on my recent trip to Greece was ancient Epidaurus, home to the magnificent theatre, and the Sanctuary of Asclepios, one of the great centres of healing in the ancient world. I’ve been to this site a few times before, and never get tired of it. More on ancient Epidaurus in a later post.

It was a scorcher of a day on the archaeological site, the cicadas whirring, the smell of pine and wild thyme in the air. After a few hours, we left the site with one more stop in mind: the ceramic workshop and store, Ceramotechnica Xipolias.

Now, in Greece, there are many stores that sell pottery. It’s one of the tourist staples. However, there are few places where you can see the actual workshop, and speak with the artists.

I visited the Ceramotechnica Xipolias on my first visit to Epidaurus years ago, and have returned other times. Their museum replicas are some of the best around, they are generous with their time, and they don’t pressure you to buy while browsing.

I always look forward to stopping there and picking up a new piece…or a few. This place, to me, is like a candy shop to a child. I missed it on my last visit to Greece, so it was time to go back!

Ceramotechnica Xipolias has been run by the Xipolias family since the mid-seventies, and it is a testament to the quality of their work, and the friendliness of the people that it is still going strong.

When we pulled up in our car, it was during the afternoon lull, or siesta. The place was quiet, dark even, and I worried that we had missed the opening hours.

Luckily, the door opened and the lights flickered on to reveal rows of welcoming shelves chock-full of history. Some music came on, and out came Dimitra Xipolia, the proprietor, and one of the nicest people you’ve ever met. She greeted us warmly and invited us to look around.

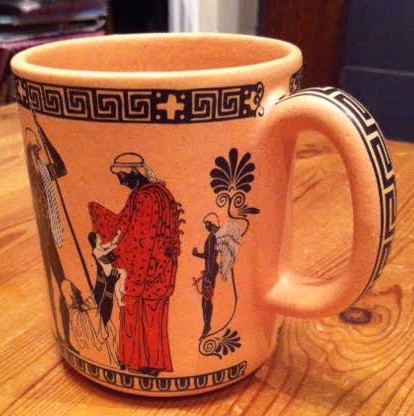

So we did. I felt giddy as I walked among the rows of museum replicas of the Geometric, Minoan, and Mycenaean periods. The work was fantastic, so detailed, so accurate, and very affordable. I started making my mental list right away!

After a few minutes of browsing, Dimitra invited us to see how a Pythagoras cup works. I had never heard of a Pythagoras cup before, so I was thrilled to see how it worked. Dimitra told us that apparently, Pythagoras wanted his students to have equal measures of wine in class, so he invented this cup with a sort of rise in the middle and a line around the edges.

Students were to fill their cups only to the line, and so, get equal measures. But, if a student got greedy and filled it passed the line, all of the contents would leak out a hole in the bottom of the cup and onto the floor! I’m not sure of the exact science behind it, but it was fun to witness.

After that, we spoke with Dimitra about Ceramotechnica Xipolias, and she explained that all their work is made and painted in-house, by family members, and that all the paints, clay etc. are non-toxic.

After always being so careful about avoiding toxic products, I found it shocking that these lovely mugs, cups, dishes, pitchers, and so much more, were perfectly safe for everyday use, even safe for children! In addition to being non-toxic, Dimitra explained that their work is also dishwasher and microwave safe.

Once I heard that, my mental list got bigger, not just because of the beauty and quality of the work, but also because back home, it’s very difficult to find such non-toxic quality at an affordable price.

I picked out a few pieces, including what I’m calling my ‘writer’s mug’ for coffee. I love the scenes of the ancient world that are painted on their products, as they provide me with a lot of inspiration as I work. But there are also many unique pieces on display, not just historical replicas.

After I chose a few pieces, Dimitra invited me to walk around. In the pictures that are part of this post, you can see the area where the painting is done, the massive kilns where the pottery is baked, and the potter’s wheel where the clay is shaped into numerous designs reminiscent of the ancient world.

Our time at Ceramotechnica Xipolias was not just about picking up a few souvenirs. It was about learning and appreciating art and ancient ceramic making techniques. Our visit was about tradition, and with such a warm welcome, it also felt like a visit with friends.

I’m glad to say that all of our pieces made it back home without a crack, thanks to Dimitra’s expert wrapping.

When we have people over now, these works of art are also centrepieces of conversation. Our friends ask about the fantastic olive dish we have on the table, or the mythological scenes on our new cups. And that’s when I talk about the people who made them.

In this age of mass produced-everything, it’s refreshing to hold a product that is handmade with precision, care, and artistry. It’s also of utmost importance these days to support local artists and industry, in Greece and around the world.

I asked Dimitra if they ship around the world, and they do, with a guarantee that if something breaks in transit, they’ll replace it. With the holiday season around the corner, perhaps this is something to consider when shopping for your favourite history-lover or philhellene.

You can check out Ceramotechnica Xipolias’ work on Etsy, Facebook, and on their website at www.xipolias.gr. On the website there are just a few examples of the fine work they do. As you can see in my photos, they have a lot more on offer. If you place an enquiry via the ‘Contact Us’ tab to let them know what you are looking for, I’m sure they’ll be more than willing to accommodate.

Giassou for now!

Thank you for reading.

End of a Summer Odyssey

Greetings readers and fellow history-lovers.

Well, I’m back from my adventures across the sea, and I had an amazing, blessed time.

I tried to keep you all up-to-date via the Instagram feed, but my Peloponnesian connectivity was a bit dodgy.

Needless to say, I’ve got a tonne of pictures and some video which I’ll be sharing with you over the coming months.

I didn’t get to all the sites I wanted to see, but I did manage to visit the ancient theatre and agora of Argos, which I’ve wanted to see for years. I also made return visits to the theatre of Epidaurus, as well as the Sanctuary of Asclepios there. In Athens, I made a return visit to the Acropolis, and the new museum which was amazing.

Normally, I would have taken in many more sites, but this trip was more about family and friends for me. That said, just driving across the landscape in Greece, or swimming in the turquoise sea, is not only inspiring, it’s also a form of research. This ancient landscape, especially in the Peloponnese, remains relatively unchanged, from the incredible light and colour, to the flocks of goats and sheep bounding up mountainsides, to the whirring of cicadas in the dry, pine-scented heat. You step back in time in rural Greece.

I’ll share my experiences of the sites and more with you in future blog posts.

As for the book I had planned on finishing, well… let’s just say that the goal I had set myself was unrealistic. I managed to finish about a third of Heart of Fire, and I’m happy with that. Here’s why:

For the first half of the trip, I was getting up at about 7 am every morning to write outside for a couple of hours, but, as the ‘schedule’ began to fill with visits from dear friends and family I hadn’t seen in a long time, it became harder to squeeze in the writing time. Worse, I began to stress about getting that writing time!

That’s when I had an epiphany.

I realized that my vacation was slipping by, and that I was wasting my precious time worrying and not relaxing. After all, isn’t that what vacations are for?

I also remembered that, in the past, I wasn’t trying to squeeze in writing while on vacation. I was always absorbing the history, the sights, the smells, and the feel of the world around me.

The writing was always something that came afterward, when I was missing the places I had been to, reviewing my mental tapes of the entire odyssey. I forgot that I would have an acute case of the ‘Aegean Blues’ after my trip, and that this would be something I could use well after the fact.

So, about half-way through my trip, I stopped worrying and began to absorb and enjoy much more. I wrote when I could, but I just let it go if the day was not conducive to it – plenty of time to write afterward.

I’m happy with what I’ve written of Heart of Fire so far, though as often happens when writing historical fiction, there are a few research gaps I need to fill in. That’s fine, as it keeps me immersed in the period.

This was a wonderful holiday and it reminded me what a lovely country Greece is, the land, the sea, the history, the people. I miss it already, and I can’t wait to go back.

I’m struggling now, back in my cubicle. Honestly, who wouldn’t? But I’m writing full speed ahead.

On Friday, I finished the first draft of an Eagles and Dragons series prequel novel which I have kept secret till now (more on that to come!). It’s called A Dragon among the Eagles.

Now, I’m going to stay put in the year 396 B.C. and Heart of Fire, until the story is completed.

That’s the update for now.

Thanks for following along, and thank you for reading!

Pythagoras’ Golden Verses – For a Good Life

There has been a lot of negativity in the news these past weeks, mostly directed at Greece and Greek people. Many comments, including from high-profile public personages, have been outright prejudiced.

Don’t worry. I’m not going to get into politics, who’s right, and who’s wrong, and how only the bankers seem to be winning anything.

Ok, I slipped there. Sorry.

With all the hatred and vitriol floating around the Web, I needed to go back to something uplifting, something ancient.

I went back to a bit of research I had done on Pythagoras and the Golden Verses. These are a series of seventy-one rules for living that were popular from antiquity and into the middle ages. It is presumed that these verses were what dictated the way of life for Pythagoras and his followers, known as Pythagoreans.

Most people today think of mathematics when they hear the name of Pythagoras, the Pythagorean Theorum having haunted many a youth in their school days, especially those not inclined to enjoy arithmetic. Myself included. I still shudder to think of it.

What many may not know is that Pythagoras was also a philosopher and mystic who influenced later philosophers, including Socrates and Plato.

Pythagoras was from the island of Samos which he left in c.531 B.C. to settle in Croton, southern Italy (then, Magna Graecia), where many ancient Olympic champions hailed from. In Croton, Pythagoras established a religious community. They believed in reincarnation and refused to offer sacrifices to the Gods, though they believed in and worshiped the Gods. If you think about that for a moment, that last point was pretty revolutionary for the time.

Pythagoras died in Metapontum (in modern Apulia, Italy) in c.497 B.C., and from then the Pythagoreans spread throughout the Greek world to spread his teachings, the Golden Verses among them.

The list of Golden Verses is quite long so I won’t list them all here. To read the entire list, check out this Wikipedia link.

To offset the negativity that seems to plague the world of late, I thought I would share a few of Pythagoras’ Golden Verses that stand out to me.

1 – First worship the Immortal Gods, as they are established and ordained by the Law.

5 – Of all the rest of mankind, make him your friend who distinguishes himself by his virtues.

7 – Avoid as much as possible hating your friends for a slight fault.

11 – Do nothing evil, neither in the presence of others, nor privately;

12 – But above all things respect yourself.

13 – In the next place, observe justice in your actions and in your words.

18 – Support your lot with patience, it is what it may be, and never complain at it.

19 – But endeavour what you can to remedy it.

20 – And consider that fate does not send the greatest portion of these misfortunes to good men.

27 – Consult and deliberate before you act, that you may not commit foolish actions.

32 – In no way neglect the health of your body;

33 – But give it drink and meat in due measure, and also the exercise of which it needs.

35 – Accustom yourself to a way of living that is neat and decent without luxury.

40 – Never allow sleep to close your eyelids, after you went to bed,

41 – Until you have examined all your actions of the day by your reason.

42 – In what have I done wrong? What have I done? What have I omitted that I ought to have done?

43 – If in this examination you find that you have done wrong, reprove yourself severely for it;

44 – And if you have done any good, rejoice.

66 – And by the healing of your soul, you will deliver it from all evils, from all afflictions.

69 – Leave yourself always to be guided and directed by the understanding that comes from above, and that ought to hold the reins.

There you have it. A bit of wisdom whispered to us across the ages. Whatever we glean from Pythagoras’ words, we can be sure that a life lived with kindness, charity, introspection and honesty is indeed a good life, and something to be grateful for.

Thank you for reading.

Tiryns: Mycenaean Stronghold and Place of Legend

This week, I wanted to leave behind the sad and depressing subject of the destruction of heritage to write about a site steeped in myth and legend – Tiryns.

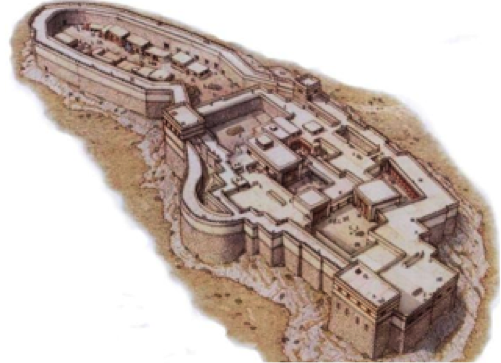

“In the south-eastern corner of the plain of Argos, on the west and lowest and flattest of those rocky heights which here form a group, and rise like islands from the marshy plain, at a distance of 8 stadia, or about 1500 m. from the Gulf of Argos, lay the prehistoric citadel of Tiryns, now called Palaeocastron.” (Heinrich Schliemann; Tiryns; 1885)

I visited the site with family during the summer of 2002. It was a scorcher of a day and the cicadas were whirring full force by 9 a.m. Luckily, the heat meant that the place was devoid of visitors – the perfect time to explore.

Tiryns is one of those sites that you likely know about if you’ve studied classics, mythology or archaeology. Most people haven’t heard about it. It lies in the broad Argive plain, a fenced-in circuit wall along the road between Nafplio and Argos itself, surrounded by orange and olive groves.

At first glance, there is no hint that Tiryns was one of the major Mycenaean power centres of the Bronze Age. The cyclopean walls are big, impressive, but there have been times when I drove by and didn’t even notice it. Perhaps that was due to the madness of driving in Greece.

When we got out of the car, the hot wind whipped across the plain to envelope us and, once we paid our entrance fee at the small kiosk, it seemed to sweep us up the ramp to the citadel, and back in time.

Tiryns is a place of myth and legend. It’s been inhabited since the 7th millennium B.C., but by the Hellenistic and Roman periods, it was already in the death throes of a swift decline. Pausanius visited as a tourist in the 2nd century A.D.

“Going on from here [from Argos to Epidauros] and turning to the right, you come to the ruins of Tiryns… The wall, which is the only part of the ruins still remaining, is a work of the Cyclopes made of unwrought stones, each stone being so big that a pair of mules could not move the smallest from its place to the slightest degree. Long ago small stones were so inserted that each of them binds the large blocks firmly together.” (Pausanias; Description of Greece)

I’ve spoken before about the feel of a place of great antiquity. Tiryns is a truly ancient place.

In mythology, it was founded by Proitos, the brother of Akrisios, King of Argos and father of Danae, the mother of Perseus.

It was said that the walls of Tiryns were built by the Thracian Cyclopes of the ‘bellyhands’ clan before they built the walls of Mycenae and Argos. This is why this style is called ‘cyclopean walls’. They were known as the ‘bellyhands’ because that clan of the Cyclopes were said to have made their living through manual labour.

It would have been a feat of tremendous strength to say the least, as each stone weighs several tons.

The association with Perseus is indirect as he acquired Tiryns after he killed his grandfather, Akrisios, but before he established Mycenae.

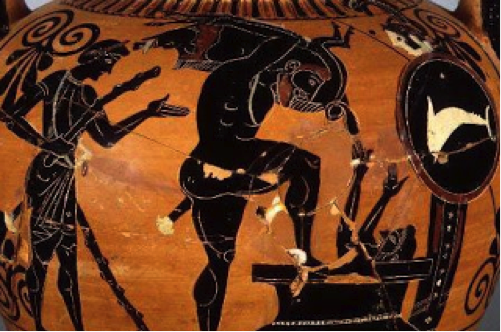

One of the most important mythological associations with Tiryns, however, is with Herakles, son of Zeus and Alkmene. The latter was the granddaughter of Perseus.

Let us go back to the time when Eurystheus was king of Mycenae, Tiryns and Argos (Note: Eurystheus was not a king of Athens, as portrayed in the recent film, Hercules.)

According to Apollodorus:

“Now it came to pass that after the battle with the Minyans Hercules was driven mad through the jealousy of Hera and flung his own children, whom he had by Megara, and two children of Iphicles into the fire; wherefore he condemned himself to exile, and was purified by Thespius, and repairing to Delphi he inquired of the god where he should dwell. The Pythian priestess then first called him Hercules, for hitherto he was called Alcides. And she told him to dwell in Tiryns, serving Eurystheus for twelve years and to perform the ten labours imposed on him, and so, she said, when the tasks were accomplished, he would be immortal.”(Apollodorus; Book II)

After Hera drove Herakles mad, causing him to kill his own children, the Oracle at Delphi told the hero that he needed to serve King Eurystheus to atone for his horrible actions.

Herakles settled in Tiryns. His twelve tasks, or Labours, for Eurystheus are legendary and have been depicted in art for centuries throughout the ancient world. You can read a previous post about the triumphs of Herakles HERE.

Admittedly, when I visited Tiryns I had no idea of its associations with Perseus or Herakles. For me, a lot of research is sparked after visiting a site, and as a result, a follow-up visit is certainly in order.

The citadel of Tiryns is about 28 metres high, 280 meters long, and it was built in three stages. In the 12th century B.C. it was destroyed by earthquake and fire but remained an important centre until the 7th century B.C. when it was a cult centre for the worship of Hera, Athena, and Herakles.

The Late Bronze Age (1600-1050 B.C.) was the height of Tiryns’ existence. It’s during this time that the cyclopean walls and most of the fortifications were built.

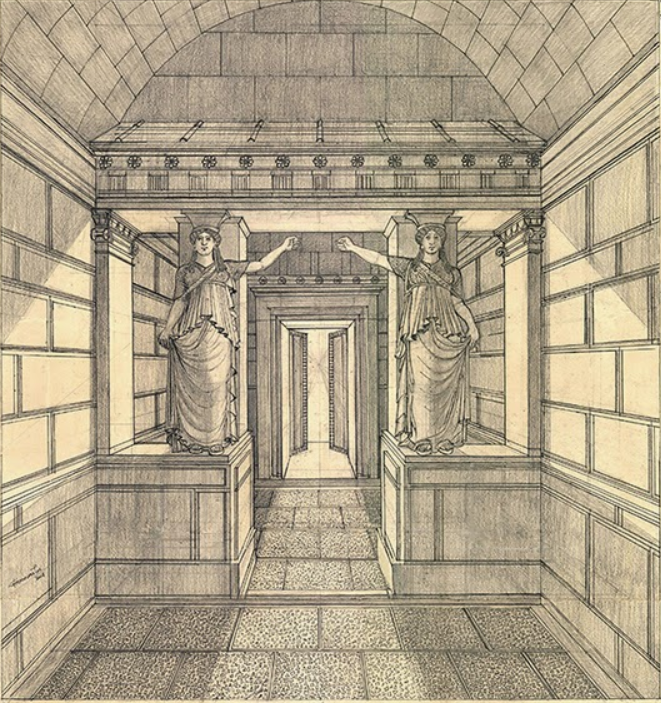

Today, as in the Bronze Age, one approaches the citadel on the east side. To get to the upper citadel, which was the location of the great megaron and palace, you must walk up a massive ramp that is 47 metres long and 4.70 metres wide. This would have led to the main wooden gates.

Once past the gates, you walk along what was a corridor that led to the Great Gate which was flanked by a tall tower. The Great Gate was almost the size of the famous Lion Gate of Mycenae, and would have proved an imposing structure.

When I was walking along the ramp, looking up at the remains of the massive walls and the tower, I could imagine warriors in bronze, with boar’s tusk helmets, looking down on me, with spears or bows in hand.

Even though the citadel contained a luxurious palace and baths, this would not have been an easy fortress to storm.

Once you attain the top, you find yourself on a level area looking out over the site – the upper, middle and lower citadels.

There is not much left in the way of intact walls when it comes to the palace but you can see the outlines of the many rooms, especially the courtyards and the great megaron where the King of Tiryns held court and had his throne on a raised platform overlooking the central hearth.

Imagine Herakles approaching Eurystheus to ask him what his next labour was to be, in this room. This was the heart of the palace. Other rooms would have included residences, a second megaron and even a bath, the floor of which is made up of a huge monolith.

I was a bit dazed, standing there in the heat, looking on the remains of this site with awe. It’s so very old and the ruins only hint at what was a luxurious, but defensible, palace. And that was just the upper citadel.

The middle citadel, 2 m lower, provided access to the defences and may even have contained a pottery kiln. The lower citadel, which is also surrounded by walls, may have been used as a refuge for the people of Tiryns town on the west side, in times of need.

At one point, when I was looking about the gravelly surface of the court, I spotted tiny bits of pottery. Of course, I bent down to get a closer look and picked up a shard with three black lines painted across it. Before I could contemplate the age of this piece, a loud whistle blew and a site person seemingly emerged from the rocks like an asp hiding from the midday sun. “No touching!” I heard, in heavily accented English.

Good thing she didn’t have a spear or bow.

After leaving the upper citadel, we walked down some steps to what is my favourite part of the site – the east galaria.

This beautiful arched tunnel is still intact, and with the sun shining from above, it was suffused with soft light. I immediately imagined a Mycenaean queen strolling between the light and shadow of this place, or a determined king on his way to a war council, his cloak flapping behind him, bronze-clad guards in his wake.

Such is the power of a site like this to fire the imagination.

Back to the present.

It’s funny, but whenever I find myself fed up with cold winter days where I live, I think back to that scorched but brilliant day at Tiryns, and smile. I feel warmth again. I enjoy the glint of the sun radiating off of the stone, and its sparkle far out in the Gulf of Argos.

This ancient citadel is a welcoming place where history and myth are entwined, comfortable allies. I certainly hope my path leads me there again one day soon.

Thank you for reading.

What is your favourite ancient site with mythological and legendary links?

Let us know in the comments below.

The Links Between History and Mythology – A Guest Post by Luciana Cavallaro

Today I have a special guest on the blog.

Luciana Cavallaro is the author of a series of mythological retellings from the perspectives of some fascinating women in Greek myth.

When I read her book, The Curse of Troy, I knew that I wanted to have her write a guest post for Writing the Past. Luciana has a wonderfully unique style, and she gives these accursed women of Greek myth a voice that you may not have heard before.

So, without further ado, a big welcome to author, Luciana Cavallaro!

First, I’d like to thank Adam for inviting me to be a guest blogger. I’ve been following Adam’s blog for years now and enjoy reading about the Roman history, expansion and legacy they’ve left behind and learning about King Arthur and Medieval England. The latter is not one of my strongest or favourite periods of history, but I do enjoy reading Adam’s articles. I also want to apologise to Adam. He asked me last year to be a guest blogger and at the time I was finishing up my book and then time got away from me.

Let’s get into it

I’m a bit of a fan of mythology, in particular Greek myth, but I’m not an expert or purport to be one. I love the stories, learned a great deal from them and continue to do so. What I particularly enjoy are the links between the myths and historical fact.

Before I get into that, let’s address what mythology is. Here’s a dictionary meaning:

Mythology is a body of myths, especially one associated with a particular culture, person, etc. (Collins Concise Dictionary, 1989)

I prefer Joseph Campbell’s explanation:

There is a mythology that relates you to your nature and to the natural world, of which you’re a part. And there is the mythology that is strictly sociological, linking you to a particular society.

(Interview with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth, 1986)

Myths are cultural as is history. If one digs (pardon the pun) deep enough, there is a correlation between the story and fact. Let’s take Jason of the Argonauts and his search for the Golden Fleece. In the Republic of Georgia, once annexed by Russia, the fleece of a sheep was used to trap golden grains dug from the river, or placed in the river banks and used in the same way.

Here’s a great article on this: Legend of the Golden Fleece was REAL: Greek myth originated near the Black Sea where miners used sheepskin to filter gold from mountain streams, geologists claim

I also watched a documentary of an Australian photo journalist who was trying to find the cities Alexander the Great founded in the Middle East. He watched Afghan miners use this technique to find gold in the riverbeds 4000 years on.

The journey from Jason’s home of Iolkos (Thessaly) to Georgia some distance away was dangerous. It is possible the story of the skills and craftsmanship of the Colchians who developed smelting and casting metals for agriculture and making jewellery found their way to Greece. This was something the ancient Greeks wanted, and the gold.

“Jason Pelias Louvre K127” by Underworld Painter – Marie-Lan Nguyen (2006) Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

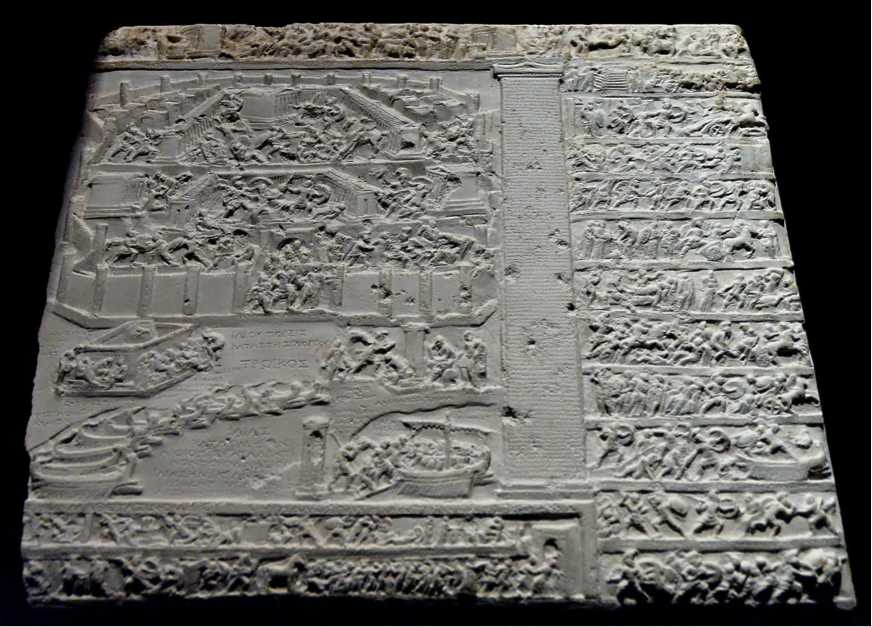

Another is the great story of Troy in Homer’s Iliad, which is a famous tourist site, and I did get to see. It is massive just as Homer stated. The lofty walls the Greeks couldn’t penetrate are there, and what is left is tall and slopes inwards. Hittite texts confirmed the site of Ilios, which they called Wilusa and identified Alaksandu/Alexander as one of the city’s kings. Alexander was the Greeks’ name for Paris. The texts also mention an invading force from the west, Ahhiyawa, that closely resembles Homer’s name for the Greeks, Achaeans. What historians have concluded is Homer’s story is a collective memory of the various invasions on Troy over centuries and its eventual downfall.

Hittite tablet recounting the events of the fall of Troy by Unknown – Jastrow (2006). Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The fact that the site of Troy exists, as does Mycenae, home of King Agamemnon, does give credence to the mythologies. But like all stories, you can’t let facts get in the way of telling a good tale.

I do believe the more we delve into the myths, the more facts we’ll find in history. As with the current series I’m writing on my blog Eternal Atlantis, on the Atlantis myth, I believe such a place did exist. Like Homer’s Iliad, the enduring legend of Atlantis is a conglomeration of memories and oral histories to explain the rise and fall of a mighty empire. Look through the timeline of history and you will find many periods of great empires and their demise, either through war or a natural disaster.

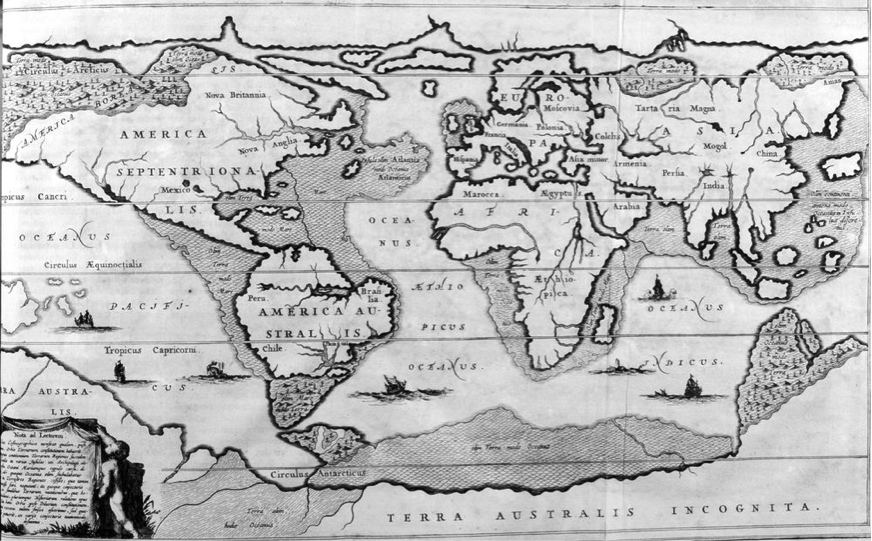

Kircher’s 1675 map of the world after the Great Flood. The location of Atlantis is marked in the Atlantic Ocean. (Print Collector/Getty Images)

Myths, like all stories, have morals and a message to relate. One day, I hope we will be smarter and take heed of these so we don’t keep repeating these transgressions. In a hundred or thousand years to come, people will question our mythology. What mythology will we leave behind?

I’d love to know your thoughts on the veracity of myths in our history.

I’d like to thank Luciana for taking the time to write this fascinating post for us. I’m so jealous of her trip to Troy, a place which I have wanted to visit for a long time. Ah, someday…

Mythology is truly fascinating, and there is a lifetime and more of stories for us to enjoy and learn from.

If you enjoy mythology as much as I do, you’ll definitely want to check out Luciana’s book, Accursed Women, or pick up one of the many short stories she has out. She also has a new book entitled Search for the Golden Serpent which I’m looking forward to reading.

Also, be sure to sign up for her E-bulletin so that you can receive her very interesting blog posts to your e-mail. By signing up, you’ll receive The Curse of Troy for FREE!

I always look forward to reading her posts as they are a fantastic escape from the everyday. The blog series on Atlantis is titantic!

Please leave any questions or comments for Luciana in the comments below, and, once again, thank you for reading…