Salvete Readers and Romanophiles!

Welcome back to The World of Sincerity is a Goddess, the blog series in which we share the research for our latest novel, Sincerity is a Goddess: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome.

If you missed the second post on theatres in ancient Rome, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In part three of this blog series, we’re going to be looking at humour and dramatic comedy in ancient Rome, including stock characters and popular themes.

Let’s dive in!

Laughing Legionaries

An Abderite [from Abdera in Thrace] saw a eunuch and asked him how many kids he had. When that guy said that he didn’t have the balls, so as to be able to have children, the Abderite asked when he was going to get the balls.

(Philagelos, #114)

Is that funny to you? Maybe a little? Or does it make you scratch your head and wonder?

The joke above is actually a Roman joke about 2000 years old. Yes, that old. It’s one of 250-odd jokes in the oldest joke book in the world known as the Philagelos, or ‘The Laughter Lover’. It is thought that this text is a compendium of jokes over several hundred years. The earliest manuscript is thought to date to the 4th or 5th centuries A.D.

Humour in the ancient world was not really something I’d thought about in my writing and research until I began work on Sincerity is a Goddess. If there has ever been humour in my books, it has been a reflection of my own modern perceptions of what humour is, or should be. Otherwise, my modern readers would be left scratching their heads.

Salve, Titus! Heard any good jokes lately?

Several years ago, I heard an interview with eminent classicist and historian Mary Beard on the subject of her book about humour in the Roman world entitled: Laughter in Ancient Rome: On Joking, Tickling, and Cracking Up. This is a wonderful book that will give you a whole new perspective on people in ancient Rome.

Anyway, until my research for this novel, my idea of humour in the ancient world was partly based on the musical A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum by the brilliant Stephen Sondheim. The latter is not a completely inaccurate view since the story is based on the farces of the Roman playwright Plautus (251–183 BC) – more on him later in this series.

Bawdiness played a large role from the theatre to the marching songs of Rome’s legionaries.

Slap stick comedy was a part of humour in the ancient world, but Professor Beard put forth the idea that there are other aspects of ancient humour which we might not, or cannot, understand.

A professional beggar had been letting his girlfriend think that he was rich and of noble birth. Once, when he was getting a handout at the neighbour’s house, he suddenly saw her. He turned around and said: “Have my dinner-clothes sent here.”

(Philagelos, #106)

When it comes to many ancient jokes, our cultural and temporal disconnect make them simply ‘not funny’. For better or for worse, depending on your point of view, we have also grown much more sensitive today.

Another reason why the humour of some ancient jokes may be lost on us is that perhaps the medieval monks copying these down simply made mistakes or interpreted them incorrectly.

Roman Comic from The New Yorker

Mary Beard has also pointed out that there is no real way to know how ancient people laughed either. This is a bit of a trickier concept to wrap one’s head around. What were ancients’ reactions to laughing? Did they have uncontrollable laughter?

My thought is that yes, maybe our jokes are different from what Roman jokes were, just like how some people find Monty Python funny (I know I do!), while others wonder what the big deal is. I also think that we are perhaps not so different in our physical reactions. For example, there is the quote from Cassius Dio, whom I have used as a source for much of my writing.

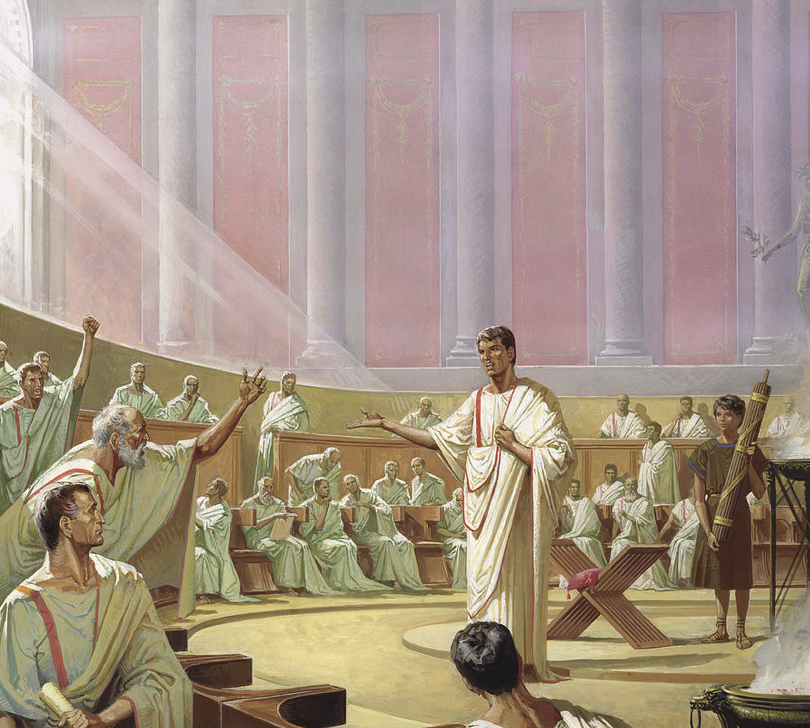

Here is a portion from the Roman History in which Cassius Dio and other senators are watching Emperor Commodus slay ostriches in the amphitheatre. As we know, Commodus was off his head, and prone to killing whomever he wanted.

This fear was shared by all, by us senators as well as by the rest. And here is another thing that he did to us senators which gave us every reason to look for our death. Having killed an ostrich and cut off his head, he came up to where we were sitting, holding the head in his left hand and in his right hand raising aloft his bloody sword; and though he spoke not a word, yet he wagged his head with a grin, indicating that he would treat us in the same way. And many would indeed have perished by the sword on the spot, for laughing at him (for it was laughter rather than indignation that overcame us), if I had not chewed some laurel leaves, which I got from my garland, myself, and persuaded the others who were sitting near me to do the same, so that in the steady movement of our armies we might conceal the fact that we were laughing.

(Cassius Dio, Roman History LXXIII)

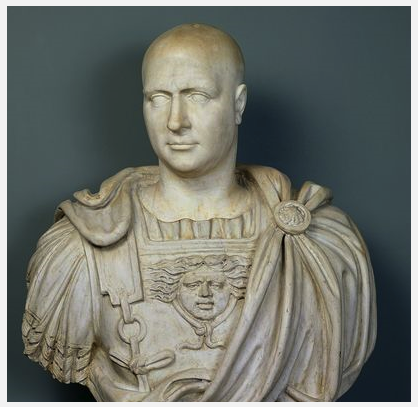

Emperor Commodus in the Arena

What a sight that must have been! Even though it meant certain death, Dio and the other senators had to chew laurels so as not to give in to what was presumably an urge to laugh hysterically.

A young man said to his libido-driven wife: “What should we do, darling? Eat or have sex?” And she replied: “You can choose. But there’s not a crumb in the house.”

(Philagelos, #244)

Bawdiness creeps in all the time in ancient humour, and why not? Everyone (well almost everyone) likes a sex joke. If you peruse the jokes in the Philagelos, you’ll see that many of them have to do with sex.

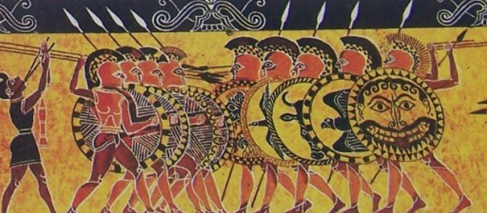

And this didn’t just apply to the Romans. The ancient Greeks found sex and humour to be comfortable bedfellows (no pun intended).

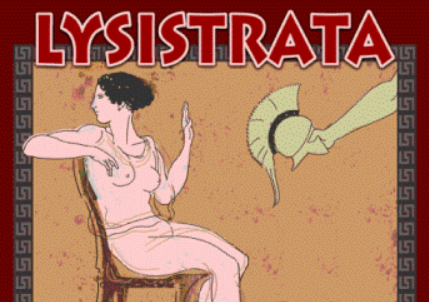

You’re not getting any until you end this stupid war!

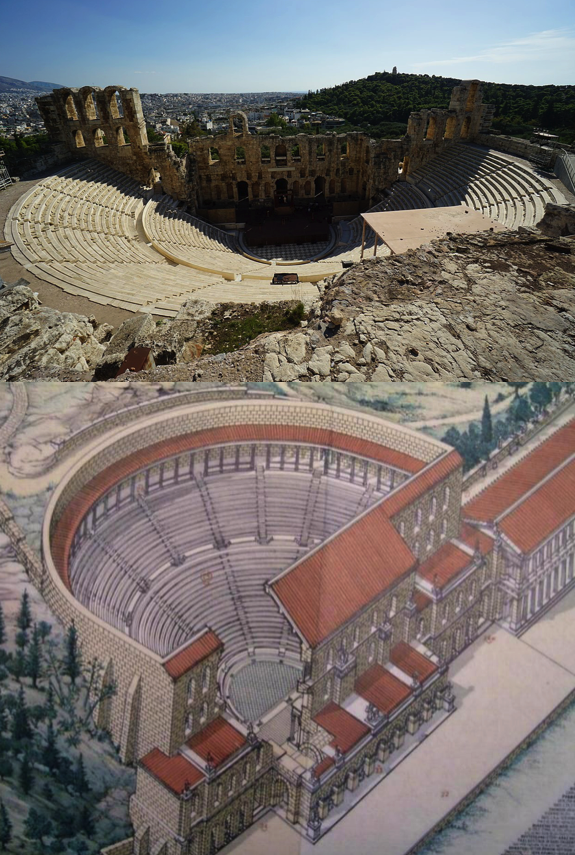

I remember going to an evening performance of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata at the ancient theatre of Epidaurus one summer night. It was a beautiful setting with the mountains as a backdrop to the ancient odeon, the sun setting orange and red, and then a great canopy of silver stars in the sky above.

Lysistrata is a play about a woman’s determination to stop the Peloponnesian War by withholding sex from her husband, and getting all other women to do the same. It seemed quite the political statement on the waste and futility of war, as well as ancient gender issues.

But then the men, who had not had sex for a long time, came prancing about the stage with giant, bulbous phalluses dangling between their legs, moaning with the pain of their ancient world blue balls. Some of the crowd roared with laughter, others tittered in embarrassment, and still others sat stock-still like the statues in the site museum.

Perhaps that is the point? Maybe in ancient times, just as today, some jokes were funny to some and not to others? Are we that different from our ancient Roman and Greek counterparts?

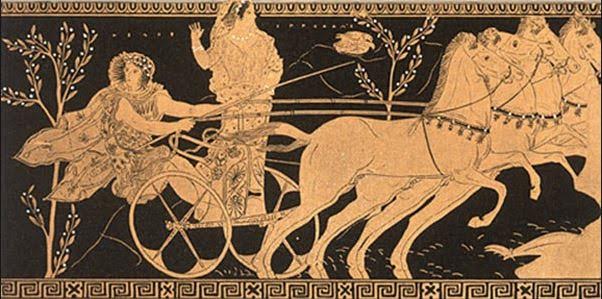

Relief of a Roman Comedic Performance

In her book, Professor Beard points out that ancient writers like Cicero speak of the different types of humour. There is derision (laughing at others), puns (word play), incongruity (pairing of opposites), and humour as a release from tension.

During my research, I found this to be a much bigger topic than I had expected. It’s fascinating to think of laughter in an ancient context.

Do I find ancient jokes funnier than before? Not really, though I do find they reveal something more of Roman society.

But what about comedy in ancient Rome, when it came to plays and the theatre?

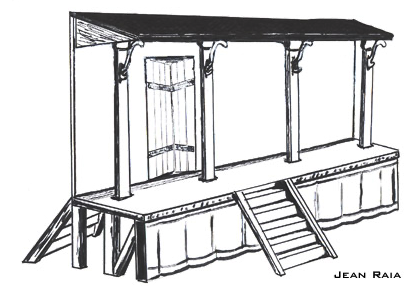

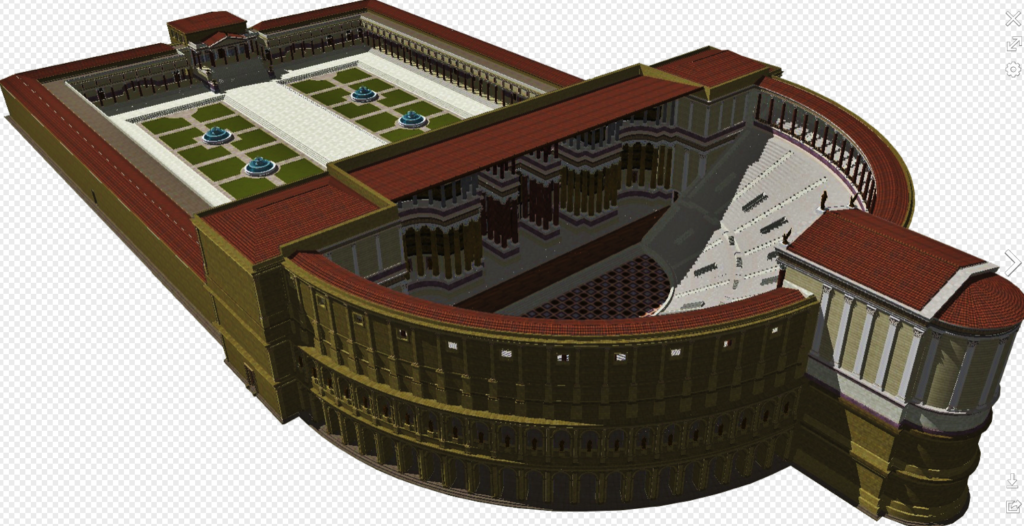

In the first part of this blog series, we discussed drama and the various types that developed in Rome, including the pantomimes, mimes, and farces.

Pantomimes tended to be tragic, and mimes were comic in nature, both being more sophisticated or high-brow than farces. Actors in pantomime and mime received training in dance, poetry, and mythology. Often, a performance involved an expressive dance by one actor accompanied by a chorus and ensemble of string, wind or percussion instruments. The artists could be very famous, bringing in large crowds. Often, the subjects of pantomimes were mythological in nature.

That said, in the world of ancient Rome, it was the racier, more bawdy and often improvised, farces, that were popular with the people.

It seems that the people, especially among the lower classes would have much preferred American Pie or Porky’s, to An Ideal Husband or Much Ado about Nothing.

How about some tickles?

Theatrical comedy in general did have certain archetypes when it came to costumes, characters, and themes.

As in ancient Greek theatre, masks, made of linen or cork, were worn, and were brown for male characters, and white for female. Purple was the colour more often worn by rich male and female characters, and red by characters who were supposed to be poor. Slaves boys in comedies were dressed in striped tunics.

Characters and themes in Roman comedy had strong links to ancient Greek comedy, especially those of Menander.

These stock characters often included the young man (adulescens), the young woman (virgo), the young married woman (uxor), the prostitute who could have her own household (meretrix), the pimp (leno), and others such as hostile fathers, unscrupulous pimps, or pirates.

The main stock Roman comedy characters, however, were most often the clever slave, the mean brothel keeper, and the boastful but stupid soldier.

The musical, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, by Stephen Sondheim, is a modern play/musical that perfectly illustrates all of these stock characters. In some ways, it is closest to Roman mimes and farces, performed as they were with an array of songs, and musical accompaniment and dancing.

Scene from A Funny thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966)