The world in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place, and with which the main characters are concerned, is also the world of the Roman legion.

Indeed, the imperial Roman legion figures largely in the entire Eagles and Dragon series, and so, I thought it good to do a brief introduction of the make-up of the legion at the time the book begins in A.D. 197.

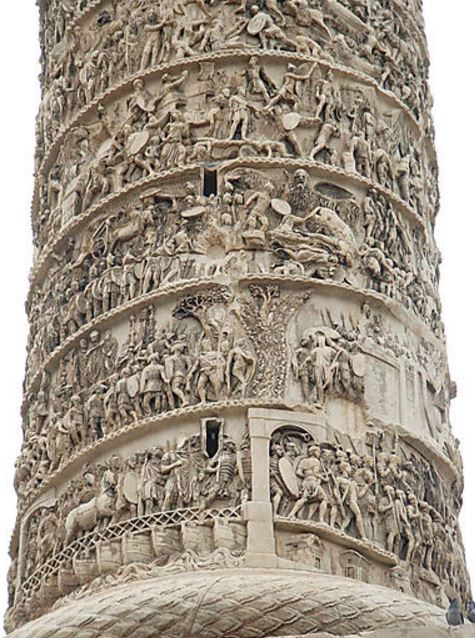

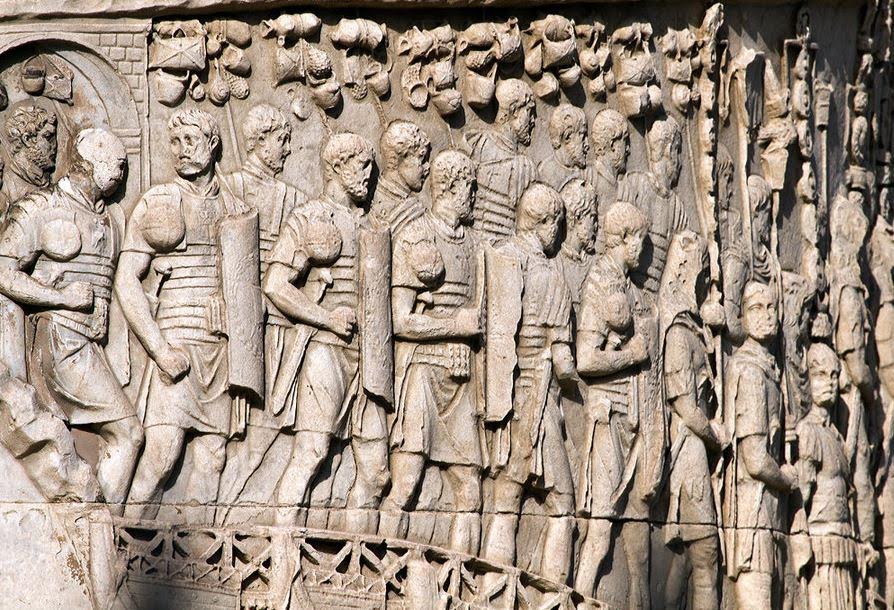

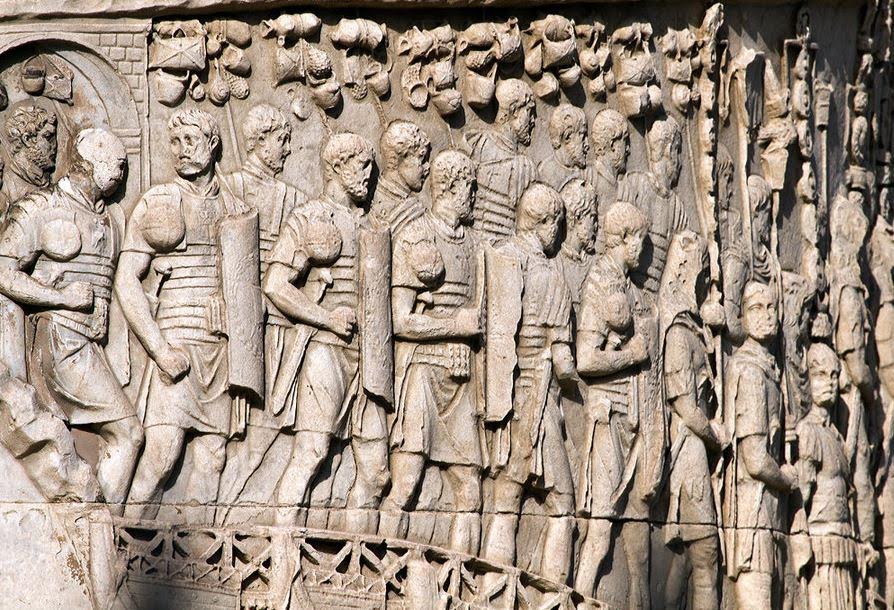

Roman legionaries on Trajan’s column

At this time in the history of the Roman Empire, the Roman legion is a well-oiled machine. It, and its troops, had been perfected after centuries of warfare, of trial and error, victory and defeat.

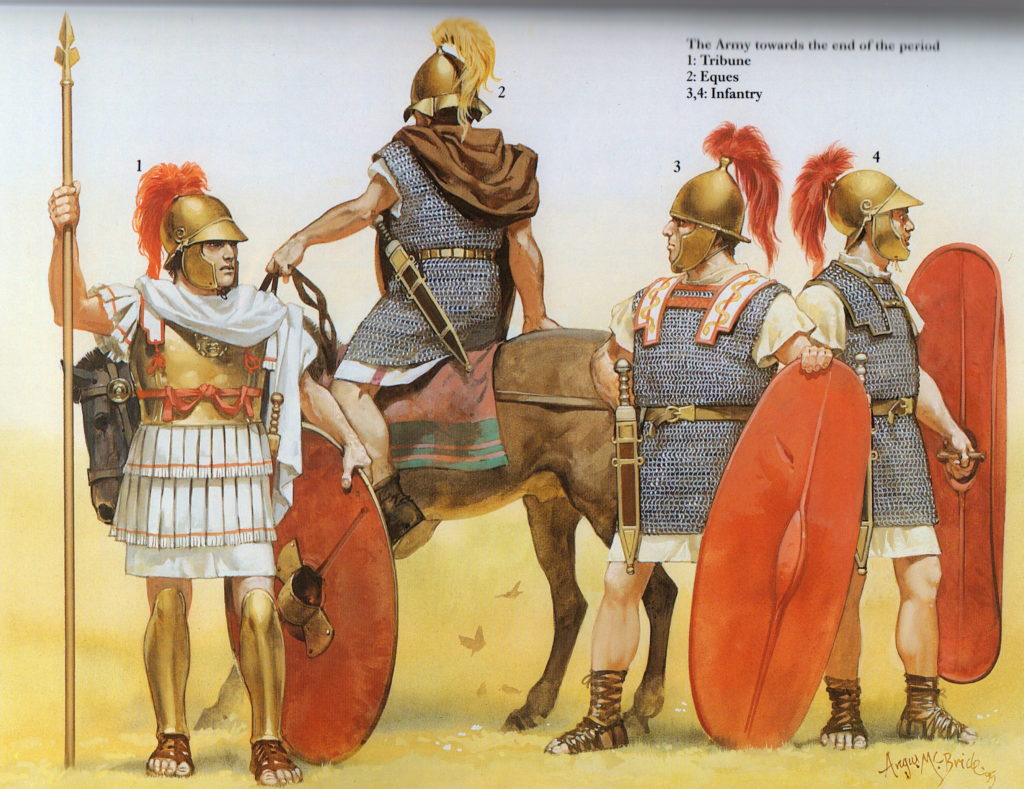

This army, the army of the Principate, is quite different from that of the Republic. It used to be that Roman legionaries were required to meet minimum requirements of possession and wealth in order to qualify for service in the ranks.

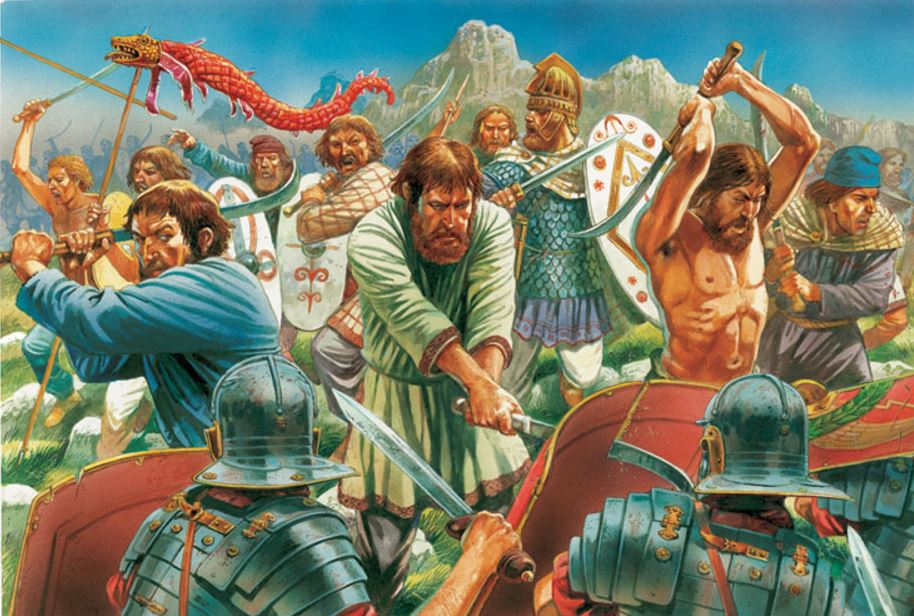

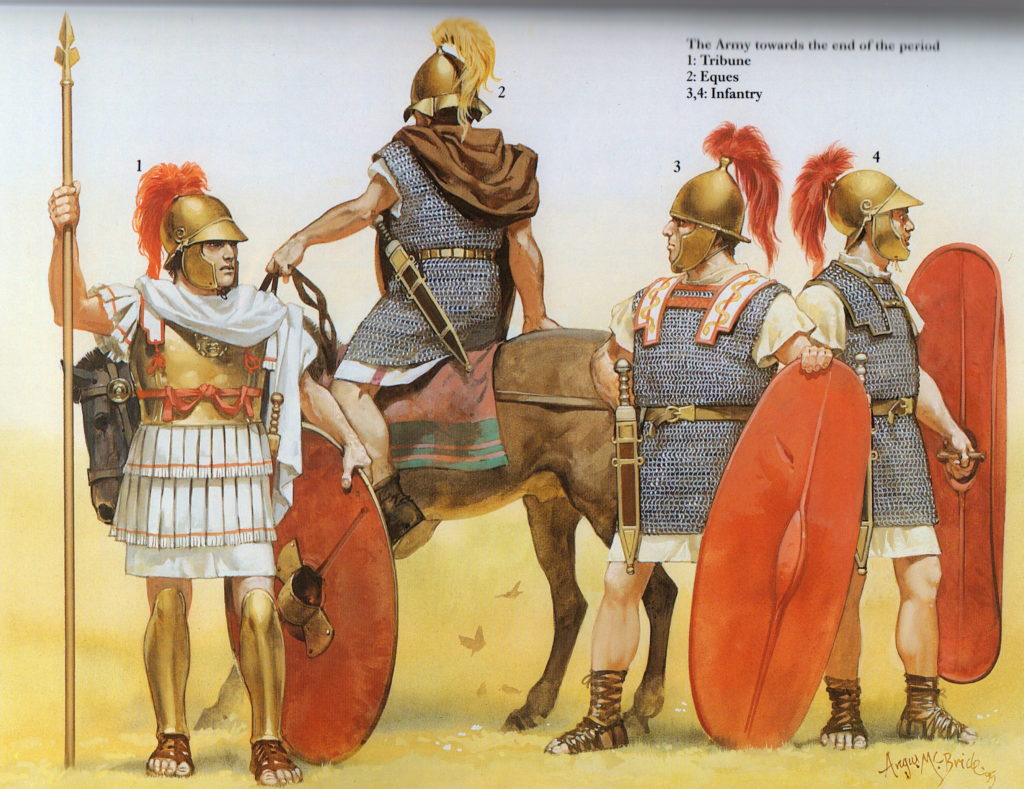

Republican Roman troops (illustration by Angus McBride)

This all changed in 107 B.C when Caius Marius was elected consul and sent to Numidia to continue the war there. However, Marius was denied the right to raise new legions in Africa, permitted only to take volunteers with him.

Of course, Marius took advantage of this, and in a move no other had taken, he appealed to the poorest classes of citizens who became known as the capite censi.

These ‘head count’ citizens were enthusiastic about joining the legions and the new opportunity for a livelihood that it presented them with. They became the backbone of the Roman Legion, and from that time onward the link between military service and property was done away with. They need only have been citizens.

Gaius Marius among the ruins of Carthage (Joseph Verner 18th century)

Marius made many reforms to the Roman army which I won’t go into here, however, his move contributed to the creation of a permanent, full-time citizen army, a self-sufficient fighting force of well-trained men with standard-issue equipment, food and lodging. They carried everything they needed on the march on their own backs, including weapons, spikes for palisades, pots, pans, and pick-axes for digging fortifications.

Marius’ Mules – Re-enactors marching in full kit

Because of all the kit they carried in the field, they became known as ‘Marius’ Mules’.

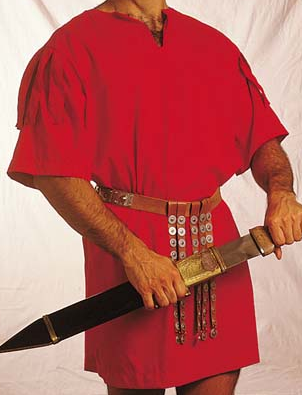

The average kit for a rank-and-file soldier in the imperial legions included hobnail sandals known as caligae, a standard tunic, a leather belt or cingulum, a lorica segmentata which was a breast plate made up of individual iron strips, a helmet, cloak, gladius (short sword), pugio (dagger), a pilum (javelin), and a scutum (shield).

Re-enactor in Roman Legionary outfit

In A Dragon among the Eagles, there is mention of the various ranks and units that make up the legion, so I think it a good idea to cover the basics now.

The smallest unit of men in the imperial legion was a contubernium which consisted of eight men who shared a tent, or barrack room. These men marched, fought, lived, and cooked together.

Then there was the century. This is probably the most well-known unit of men. It consisted of 10 contubernia, and was run by a centurion with a standard bearer and an optio beneath him.

The centurion was usually a career soldier, and a harsh task-master. He wore different armour that was chain mail, usually with a harness decorated with phalerae, decorative discs that represented awards he had been given. The crest of a centurion’s helmet was horizontal, and he carried a short wooden staff called a vinerod, which gave him the right to strike his citizen soldiers in the interests of discipline.

Re-enactor dressed as a Centurion (Wikimedia Commons)

There are stories about a particular centurion in the imperial legions whose nick-name was ‘give me another’ because he was constantly breaking his vinerod over the backs of his men!

Centuries of eighty men were the most flexible military units in the legion. They numbered enough to go on patrol, or building duty, and could manoeuvre effectively in battle.

Now, the next unit of the legion was the cohort.

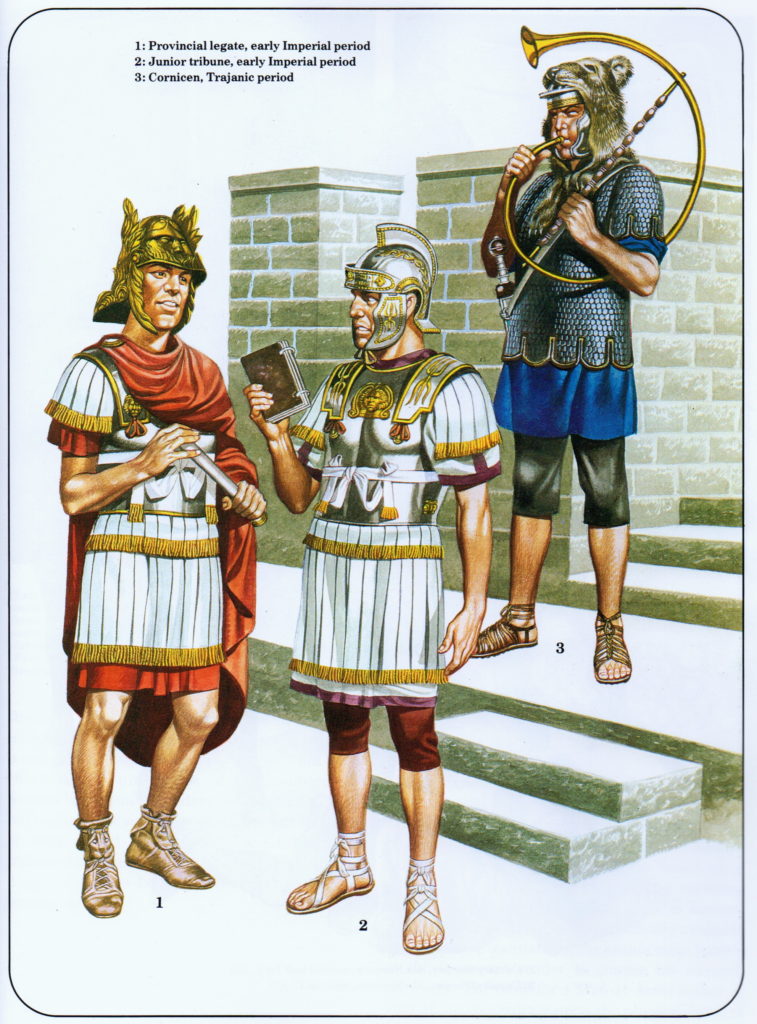

The imperial cohort was made up of 480 men, and consisted of six centuries let by an Equestrian tribune. The first cohort of a legion, however, was led by a Patrician tribune.

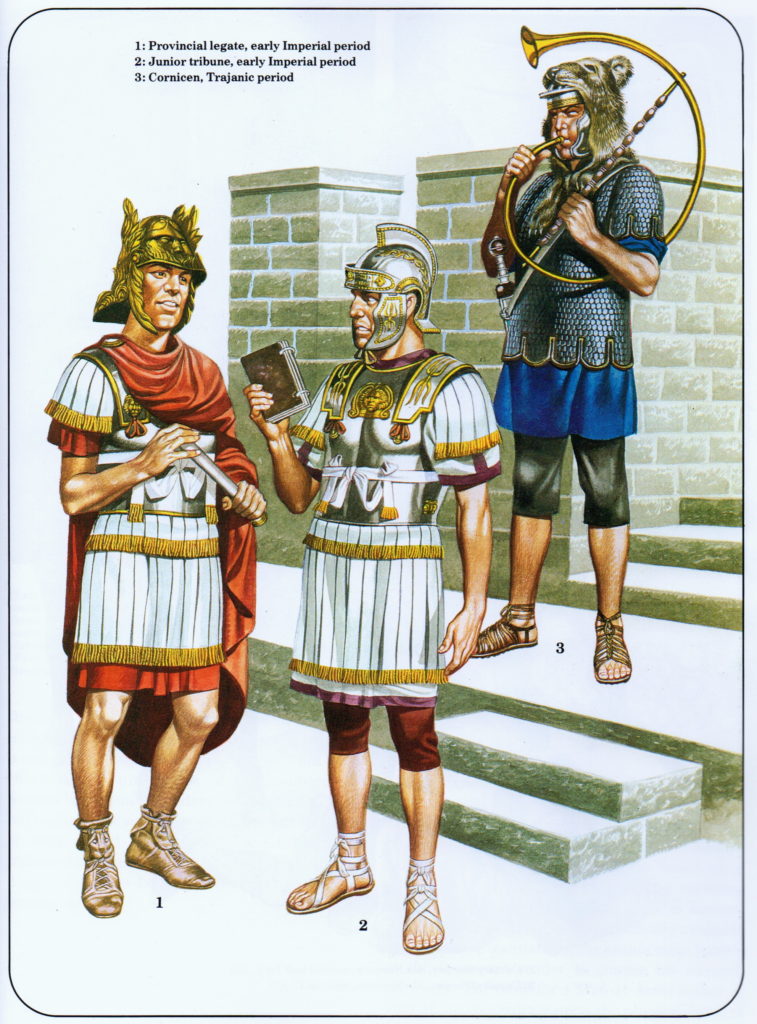

Officers of the Imperial Roman Legions (illustration by Ron Embleton)

Finally, there were ten cohorts in a legion which brought the average number of troops in the imperial legion to 5000.

The commander or general of an entire legion was known as the legatus legionis, or legate commander. This person was usually a senator, just like the patrician tribune who was his second-in-command. The third person of overall authority in the legion was the camp prefect, or praefectus castrorum. The latter was often a career soldier, perhaps a former centurion who had been promoted, and was responsible for much of the legion’s administration and logistics.

There were many other minor positions within the legions such as duplicarii, men who received double pay for skills such as engineering, or the building of siege equipment, as well as benificari, those who were aides to the legate or other officers, and who were excused for intense labour such as the digging of ditches and erecting palisades.

Roman legionary standards with an image of Emperor Severus and his family

We must not forget the standard bearers who made up the imperial legion. These included the vexillarius, the person who carried the vexillum standard of each unit, the signifer, the soldier who carried a century’s standard and wore a wolf or other pelt over his helmet. There was the cornicen, the trooper who carried the cornu, the round horn used to rally the troops and give commands, as well as the imaginifer of the legion, the trooper whose task it was to carry the image of the emperor before the legion.

Probably the most important standard bearer was the aquilifer, the man whose solemn duty it was to carry the legion’s golden eagle, the aquila, into battle. This man was to protect the legion’s eagle at all cost, for it was the ultimate disgrace for a legion to lose its aquila to an enemy.

Re-enactor dressed as an Aquilifer

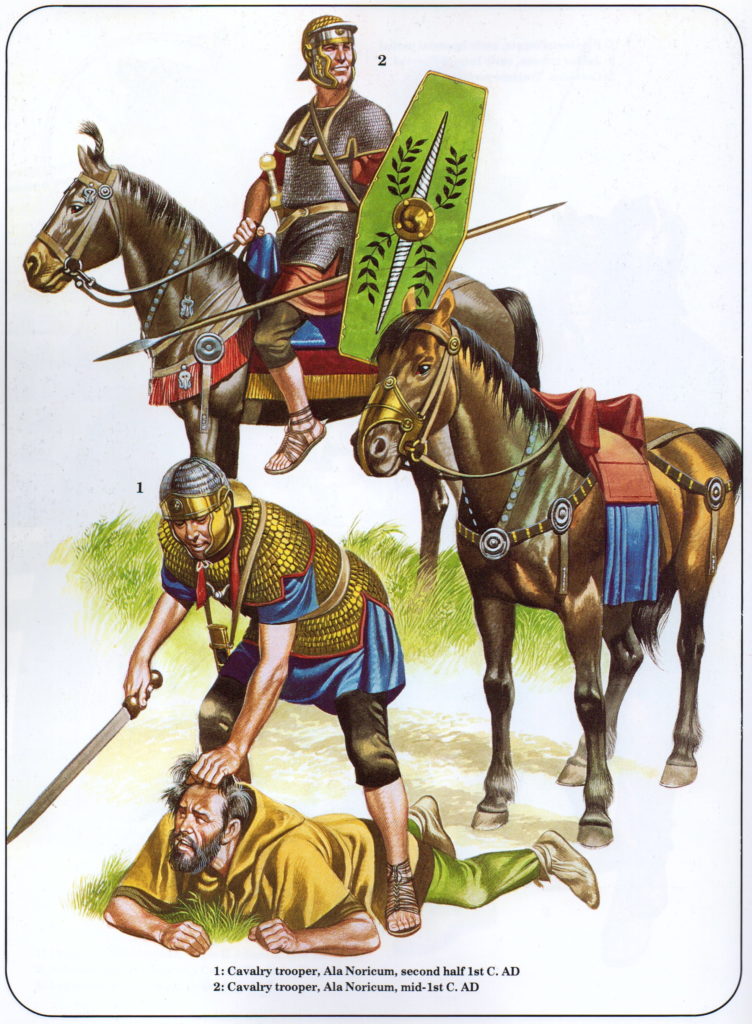

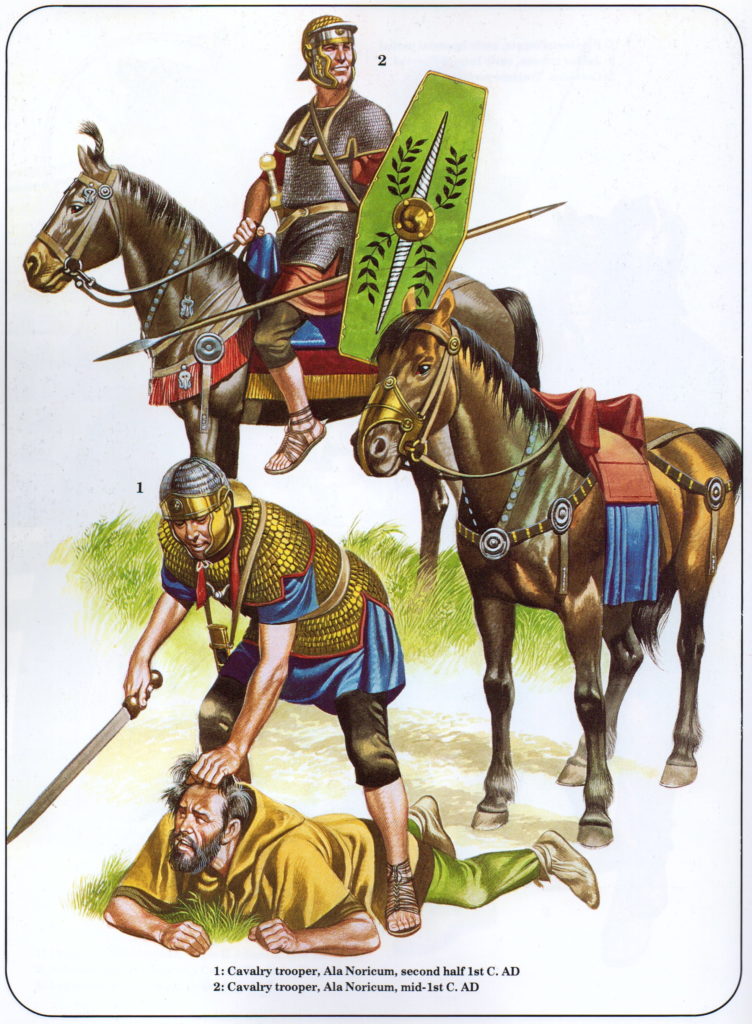

Along with the 5000 regular troops that made up an imperial legion, there were often alae, or auxiliary units, attached to the legion. These were usually units of 120 cavalrymen who acted as scouts and supported the legion on the march. They were often made up of foreign troops who had been brought into the Roman ranks such as Sarmatians, Numidians, or Scythians to name a few.

Ala units might also consist of skirmishers such as Cretan or Balearic slingers, but most often they were cavalry.

Auxiliary Cavalry troops (illustration by Ron Embleton)

The imperial Roman legion was one of the most effective fighting units of the ancient world, and it is no wonder that the Empire covered so much of the known world by the time in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place.

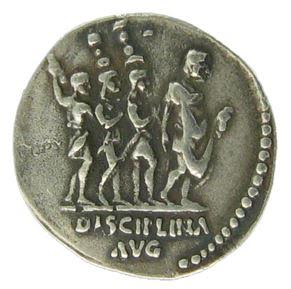

Disciplina, the goddess personification of discipline, was something that was taken very seriously. If a soldier obeyed her and remembered his training, he would survive the direst of circumstances.

Roman coin showing stardard bearers and the world ‘Disciplina’ – second century A.D.

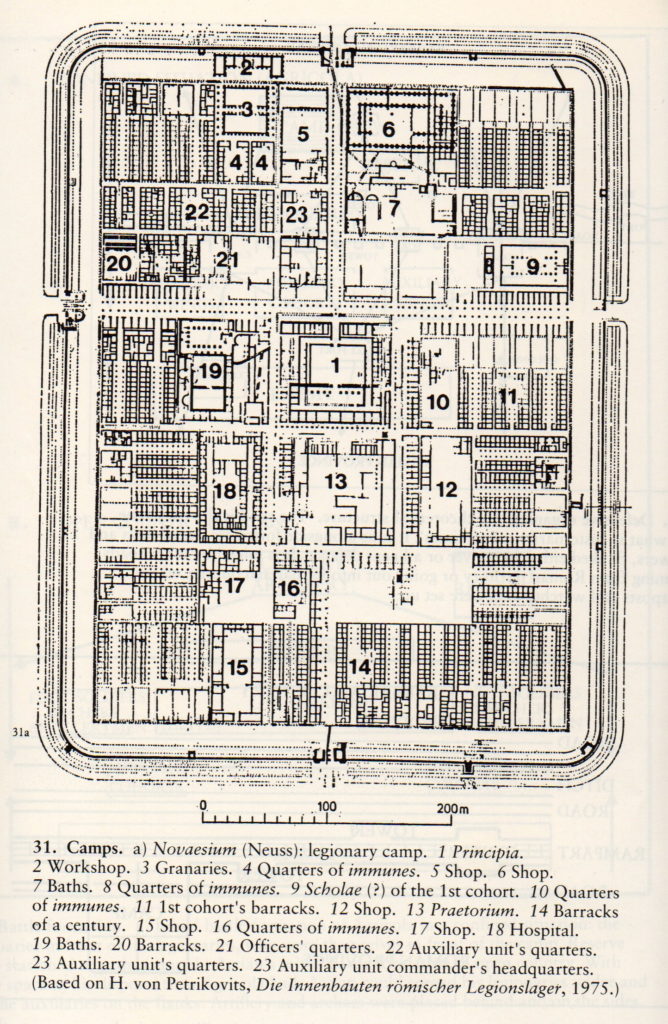

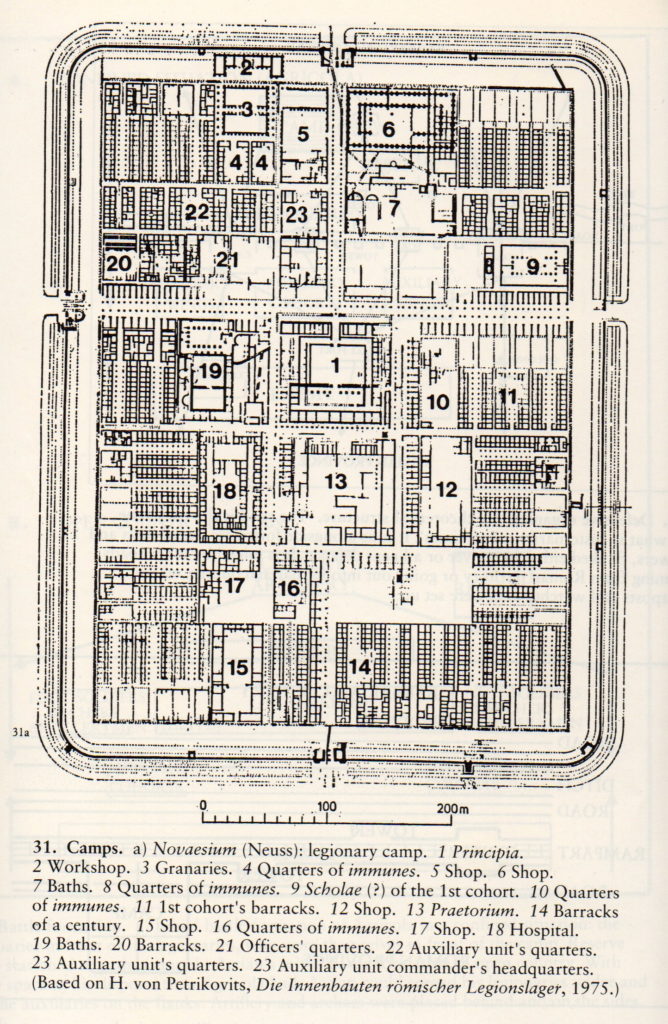

When the legions marched in the field, every night they dug in, every trooper going to his assigned space to dig ditches, pile up ramparts, and raise the palisade around the entire camp.

Tent and command centre, the Principia and Praetorium, tribunes’ tents, stables etc. were always in the same position, the streets set out in the same grid every time. So, whatever happened, a Roman soldier knew where he was, and what he had to do.

Every morning, when they would break camp, they would take down the work of the previous evening, which they had done after a twenty mile march, so that the enemy could not make use of their fortifications.

Plan of a typical legionary fortress (from The Imperial Roman Army by Yann Le Bohec)

It was hard work, but the imperial legion gave opportunity to the poorer classes of Roman citizens and allowed them to make something of themselves, if not at least be clothed and fed at the state’s expense.

In return, the men of the legions bled for Rome as they extended her borders into the world.

A Dragon among the Eagles takes place during the Severan invasion of the Parthian Empire, one of the biggest thorns in Rome’s side for over two hundred years.

In A.D. 197, Septimius Severus set out with one of the largest invasion forces in Rome’s history, made up of a titanic 33 legions.

The stage was set for one of the greatest military campaigns in Rome’s history.

In the next post, we’ll look at this powerful enemy and the tactics they used in battle against the legions.

Until then, check out this great video that illustrates the make-up of the Roman legion.

Thank you for reading!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wCBNxJYvNsY