Ancient Rome

Ancient Everyday – The Calendar in Ancient Rome

Salve!

Welcome to the second part in this mini, Ancient Everyday blog series about Time in the Roman world.

Last week we took a brief look at how the Romans tracked and organized the years. If you missed it, you can read it by CLICKING HERE.

This week, we’re going to take a look at what is perhaps one of their greatest legacies – the Calendar.

Now, the Romans did indeed do a lot for us – you can check out this wonderful series hosted by Adam Hart-Davis to learn what the Romans did for us – and it goes without saying that we take a lot of it for granted today.

The calendar ranks right up there, and even though we take time for granted, it is actually something that we are constantly aware of. Quite the conundrum, if you ask me!

The word ‘calendar’, as well as the names of the months we still use today are of Roman origin.

However, the calendar went through some reform before it got to the version we are now familiar with.

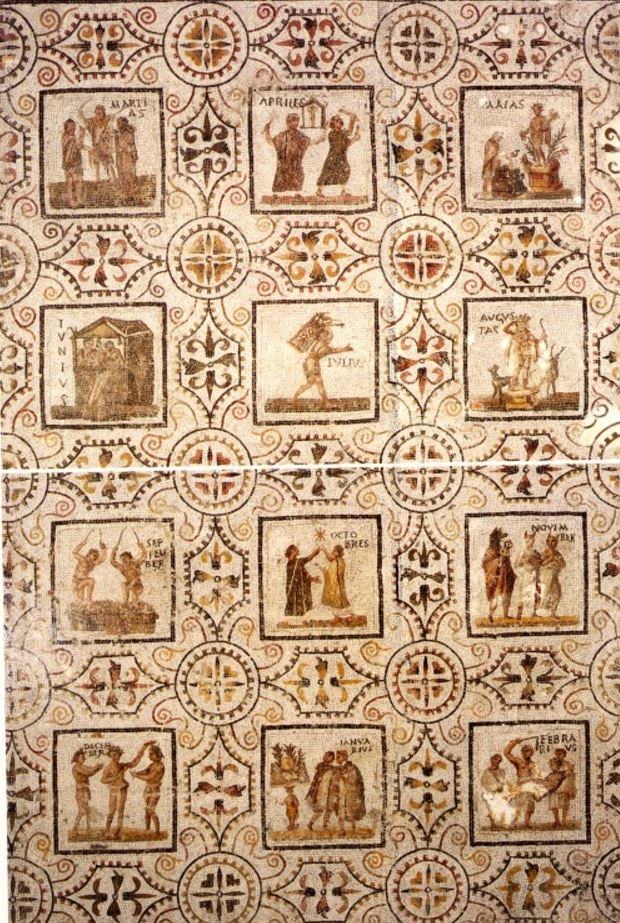

The original Roman calendar, known as the ‘Calendar of Romulus’, was an agricultural, 10-month year. There were ten irregular months with a total of 304 days from March to December.

The names of these months originated then, and the gap of missing months accounts for the period of time in which no agricultural work was carried out. This was also a lunar cycle, so there was a degree of ‘seasonal drift’ compared to the solar cycle.

It is believed that the change to a 12-month calendar occurred in the sixth century B.C.

In the year 153 B.C., January was made the first month of the year, named after Janus, the god of doorways and new beginnings.

But until Julius Caesar’s calendar reform, the Roman year was 355 days long, divided into 12 months. Four of these had 31 days (March, May, July, and October), seven months had 29 days, and February had 28 days.

Here are the names of the months on the Roman calendar:

Ianuarius (the month of ‘Janus’)

Februarius (the month of ‘Februa’, purgings or purifications)

Martius (the month of ‘Mars’)

Aprilis (uncertain meaning)

Maius (uncertain meaning)

Iunius (the month of ‘Juno’)

Quinctilis (the ‘fifth’ month – renamed ‘Iulius’ in 44 B.C. after Julius Caesar)

Sextilis (the ‘sixth’ month – renamed ‘Augustus’ in 8 B.C. after Emperor Augustus)

September (the ‘seventh’ month)

October (the ‘eighth’ month)

November (the ‘ninth’ month)

December (the ‘tenth’ month)

Notice how some of these names are a legacy of the 10-month agricultural Roman calendar year?

There is apparently some evidence for ‘intercalation’, that is, the addition of days to adjust the year. This included the addition of 22-23 days every other year in February.

The act of intercalation was the domain of the pontiffs of Rome, but it was not accurate, and by the time of Julius Caesar, the civic year was about three months ahead of the solar year that was in use.

Caesar extended the year 46 B.C. to 445 days to remove the discrepancy.

So, from January 1st, 45 B.C. he made the year 365 days long with the months at their current numbers. Quite the legacy, no? He also introduced the leap year.

Thus, was the Julian Calendar born.

Today, the most widely used calendar is the Gregorian Calendar. However, the Gregorian calendar is basically the same as the Julian Calendar except for some small changes.

In 1582 Pope Gregory XIII omitted 10 days from the calendar year to adjust the discrepancy between the Julian calendar and the solar year. He also ordered that 3 days be omitted in leap years every 400 years.

So there you have it! A very brief look at the evolution of the calendar from ancient Rome to the one we use today.

Next week, in Part III of this series, we’ll be looking at the days and weeks in the Roman world.

Thank you for reading!

Ancient Everyday – Tracking the Years in Ancient Rome

Salve!

This week on Writing the Past, we’re going back in time from the Middle Ages to ancient Rome once more.

I thought it might be fun to do a short series of Ancient Everyday blogs about something that concerned our ancient ancestors as well as ourselves. It’s something that, across the ages, we all wish we had more of: Time.

This isn’t going to be a philosophical series of posts on time, but rather a look at the practicalities of time and how ancient Romans organized it.

In this first post, we’re going to look at how years were counted and tracked in ancient Rome and across the Empire.

Today, dating is something we take rather for granted, but at times during the Roman era, there was a lot of thought put into this and the development of a system around it.

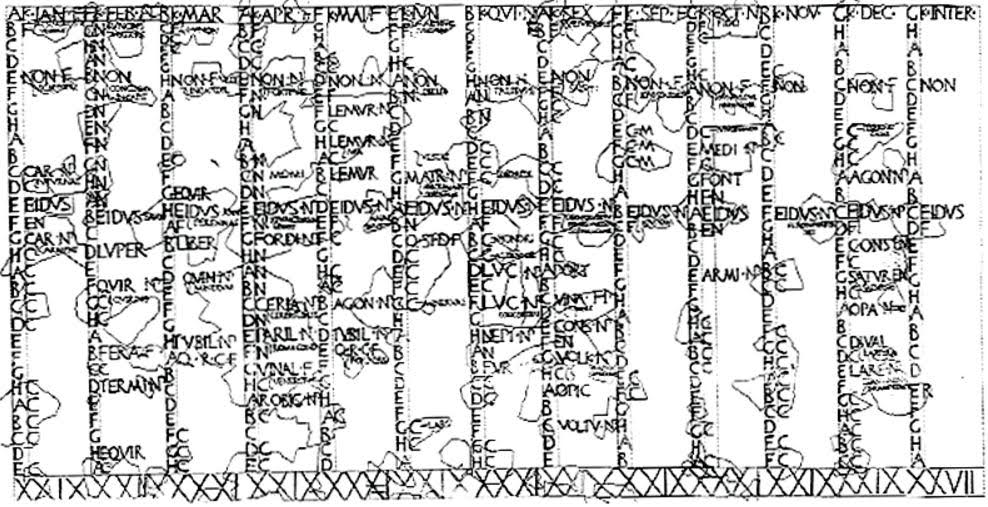

Early in the Roman Republic, the years were usually dated by the names of the Roman Consuls, the highest rank for an elected Roman official, and the pinnacle of the Cursus Honorem, the tried and true path of public offices for anyone seeking political success.

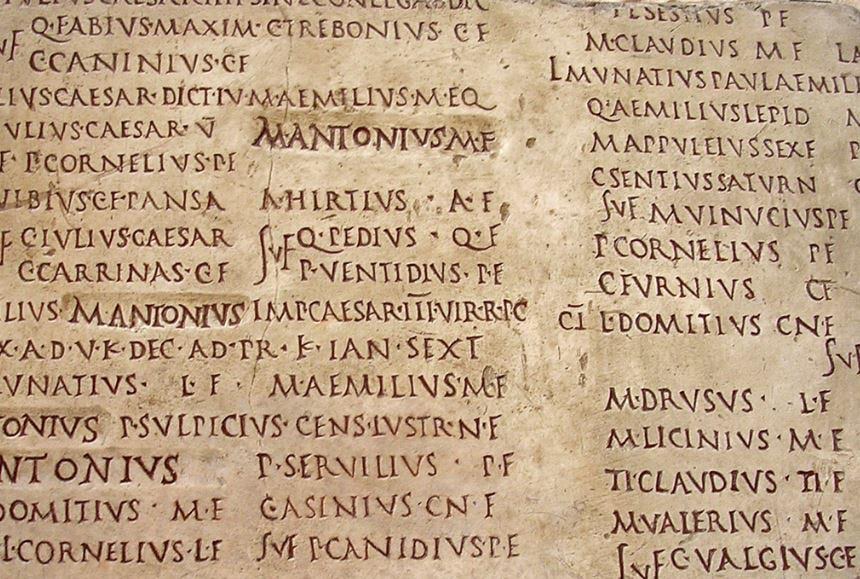

Two consuls served at once and, conveniently, they served for just one year, so that could be readily used as a method of dating. The lists of consuls were called fasti, and they exist from about the year 509 B.C.

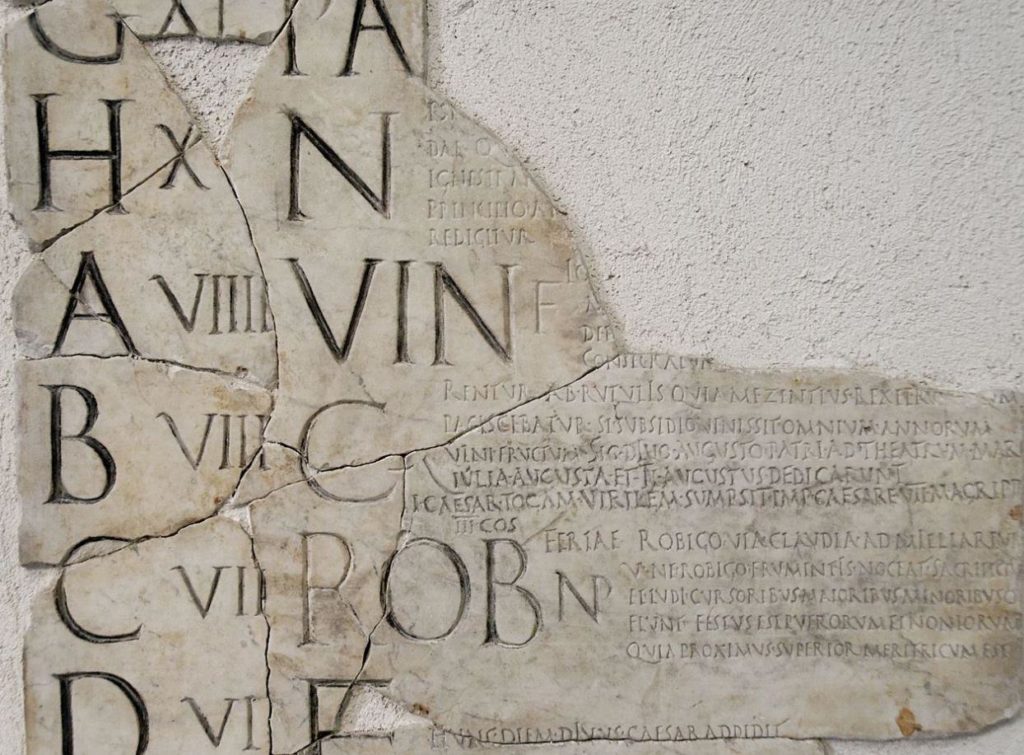

Fragment of the list of the Roman consuls known as the “Fasti Colotiani” (Museo della civiltà romana)

This practice of dating using the names of Roman Consuls stopped in about A.D. 537 when Emperor Justinian I (the ‘Great’) switched to the regnal years of the emperors.

Prior to that, there were other ways in which the years were tracked and counted.

Sometimes years were dated from the founding of the city of Rome – ab urbe condita was the wording used. Rome is generally thought to have been founded in the year 753 B.C., so the years would be counted from that point on.

I wonder how widespread this dating was, compared with the use of the fasti. There were even more dating systems across the Empire, systems which had a local flavour; say, for instance, years counted from a particularly big event in the history of a certain place etc.

From the late 3rd century A.D., the practice of counting years by indiction, or indictio, was also used. This was the announcement of the delivery of food and other goods to the government. So, basically, indictio referred to the tax assessment which took place, at first, in five-year cycles, but in a fifteen-year cycle from about A.D. 312.

Indictio was also often used to date the fiscal years in the Empire which tended to begin on the first of September.

It’s thought that the general population may have tended to know the indictio years better than the consular years. This isn’t surprising as we’re all aware of the dates when the government slashes at our purse strings!

The Christian reckoning of years using B.C. and A.D. (for Anno Domini – ‘Year of the Lord’) in the Julian and Gregorian calendars was introduced in the mid-sixth century by the monk Dionysius Exiguus of Scythia Minor. In this reckoning, there is no year ‘0’, but rather 1 B.C. is immediately followed by A.D. 1. Nowadays, there is a movement toward using B.C.E (Before Common/Current Era) and C.E. (Common/Current Era).

Whichever method of dating you prefer today, it seems that the Romans had a variety of methods to choose from.

Were they as obsessed with time as we are today? I suspect not. But it was something they grappled with on certain levels.

Either way, ancient dates are likely less reliable before Julius Caesar’s calendar reform of 45 B.C.

I suppose we should thank the gods for circa, that is, ‘approximately’!

Thank you for reading!

If you are curious and want to check out a list of the consuls of Rome, you can do so by CLICKING HERE.

Come back next week for the next Ancient Everyday in this series on Time in which we’ll be looking at the Roman calendar and months.

Mars – God of War and…Agriculture?

One of the things that fascinates me the most about studying the ancient world is the vast array of gods and goddesses. They all played an important role in the day-to-day lives of ancient Greeks, Romans, Celts and others.

There were many deities associated with agriculture in ancient Rome, Ceres and Saturn, for example. Many gods and goddesses, major and minor, could affect crops, agricultural endeavours and the subsequent harvests.

When you hear the name of Mars, agriculture is not the first thing that comes to mind. When I think of the Roman god, Mars, I think of one thing.

WAR.

The Roman God of War was second to none other than Jupiter himself in the Roman Pantheon.

The Romans were a warlike people after all, and so Mars always figured prominently.

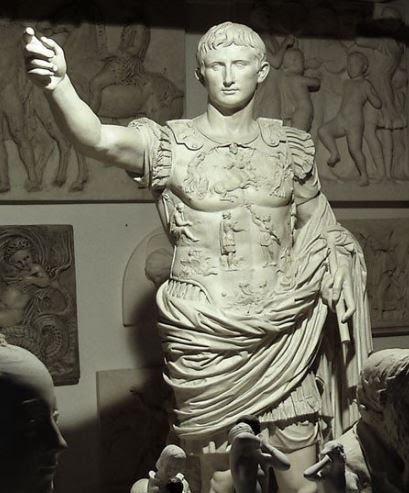

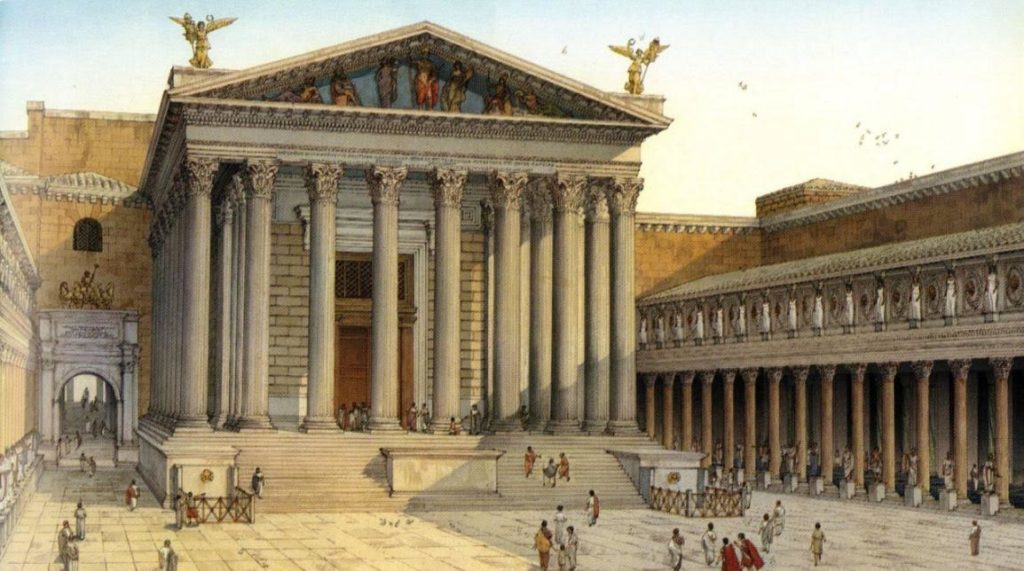

Octavian (later the Emperor Augustus) vowed to build a temple to Mars in 42 B.C. during the battle of Philippi in which he, Mark Antony and Lepidus finally defeated the murderers of Julius Caesar. When Augustus built his forum in 20 B.C. the Temple of Mars Ultor (the Avenger) was the centrepiece.

“On my own ground I built the temple of Mars Ultor and the Augustan Forum from the spoils of war.” (Res Gestae Divi Augusti)

People often think that Mars was the Roman name given to Ares, the Greek God of War, as was the case with many other gods in Roman religion. This is not exactly true.

In the Greek Pantheon, Ares was simply God of War, brutal, dangerous and unforgiving. To give oneself over to Ares was to give in to savagery and the animalistic side of war. Fear and Terror were his companions. Most Greeks preferred Athena as Goddess of War, Strategy and Wisdom.

Mars was a very different god from Ares. He was a uniquely Roman god. He was the father of the Roman people.

Mars was the God of War, true, but he was also a god of agriculture.

Just as he protected the Roman people in battle, so too did Mars guard their crops, their flocks, and their lands.

War and agriculture were closely linked in the Roman Republic. Most Romans who fought in the early legions were farmers who had set aside their plows and scythes to pick up their gladii and scuta when called upon to defend their lands. One of the most cited examples of this is Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (519 BC – 430 BC), one of the early Patrician heroes of Rome.

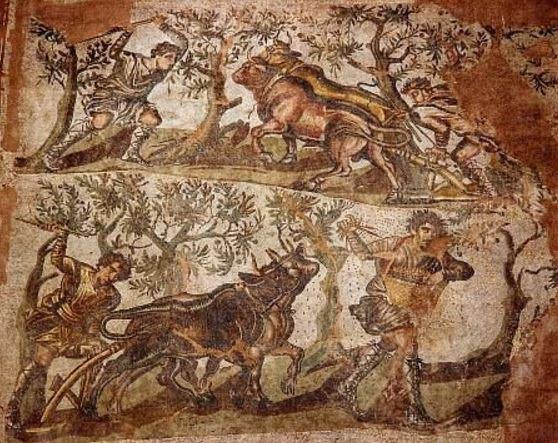

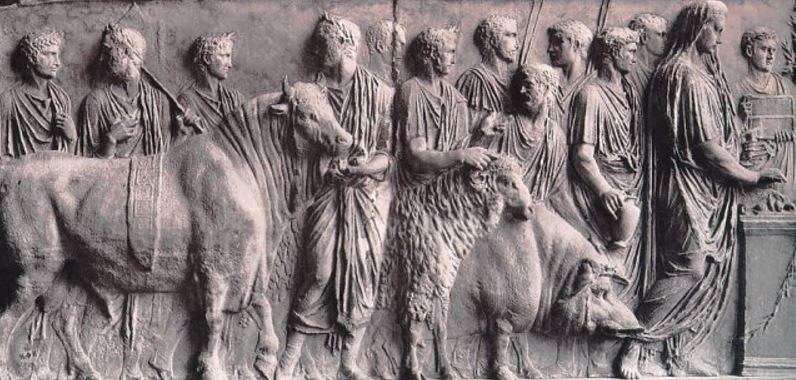

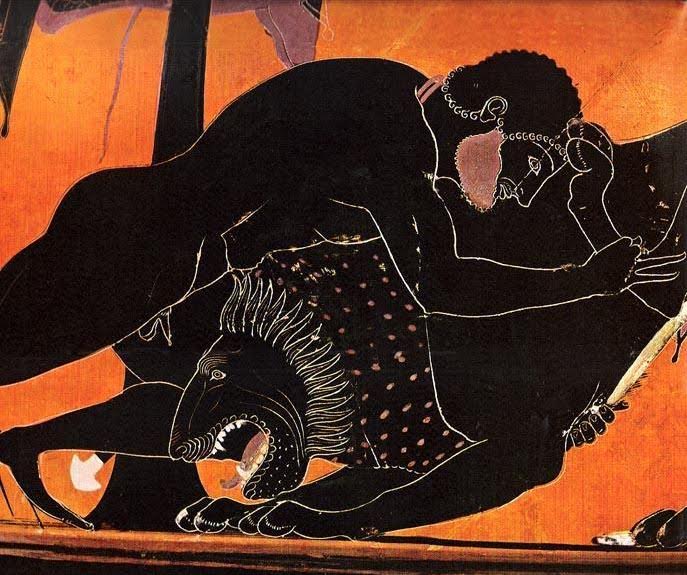

In his work De Agri Cultura, Marcus Porcius Cato (234 BC– 149 BC) speaks at length about the tradition of the suovetaurilia, a sacrifice that was made roughly every five years and occasionally at other times. This ceremony was a form of purification, a lustratio.

The highly sacred suovetaurilia was dedicated to Mars with the intent of blessing and purifying lands.

It involved the sacrifice of a pig, a sheep, and a bull – all to Mars.

The sacrifice was done after the animals were led around the land while asking the god to purify the farm and land.

Cato describes the prayer that is uttered to Mars once the sacrifices have been made:

“Father Mars, I pray and beseech thee that thou be gracious and merciful to me, my house, and my household; to which intent I have bidden this suovetaurilia to be led around my land, my ground, my farm; that thou keep away, ward off, and remove sickness, seen and unseen, barrenness and destruction, ruin and unseasonable influence; and that thou permit my harvests, my grain, my vineyards, and my plantations to flourish and to come to good issue, preserve in health my shepherds and my flocks, and give good health and strength to me, my house, and my household. To this intent, to the intent of purifying my farm, my land, my ground, and of making an expiation, as I have said, deign to accept the offering of these suckling victims; Father Mars…“

(Cato the Elder; De Agri Cultura)

This is not a prayer to the bloodthirsty god of war that Ares was.

The words and actions above evoke a wish from a child to a supreme father and protector. We see the fears that would have occupied the minds of the Roman people. No matter how mighty in war they may have been, if crops failed and disease spread, they would have been lost.

Romans prayed to Ceres and Saturn for the success of their crops, for abundance.

But the prayer above was to Mars, he who held Rome’s enemies, the enemies of its lands, at bay.

In war and in peace, Mars was always the guardian of his people.

Thank you for reading

If you want a clearer understanding of the suovetaurilia ceremony, and the meaning of this interesting Latin compound word, here is a very short presentation: https://youtu.be/pz1KiILdW2s

The Elusive Etruscans

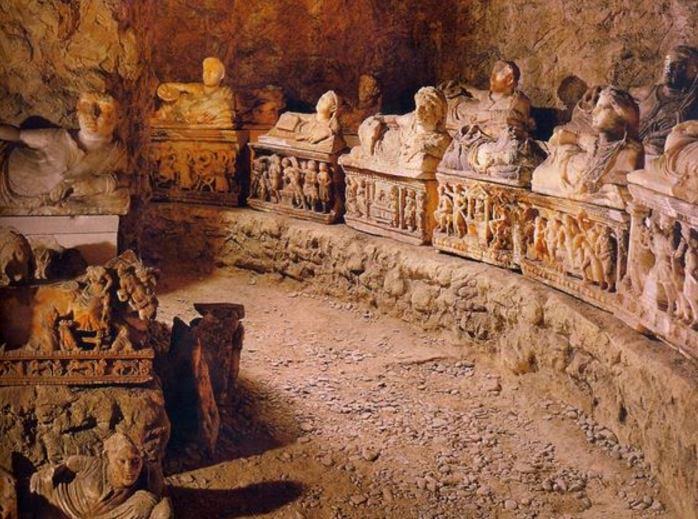

Recently, while excavating piles of my research on various topics, I unearthed some photos from a vacation in Tuscany back in 2002. These photos were of an Etruscan tomb just outside Castellina in Chianti.

The site was simple and unassuming, but it had a great impact on my imagination, so much so that I used it in some parts of Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra. On that trip, I started to learn more about the Etruscans who inhabited the Italian peninsula from roughly the Tiber to the Arno rivers and beyond, to the Po valley and Bologna.

So, my interest rekindled, I thought I would write a quick post on this fascinating people.

Not a great deal is known about the Etruscans, and I am by no means an expert, but from what I have seen and read, it’s a very interesting topic. Anyone who has studied ancient Greece and Rome will have had some contact with the Etruscans; the Greeks traded with them and were a great influence on Etruscan art and lifestyle, and Rome itself was ruled by Etruscan kings who brought that little backwater village by the Tiber out of the mud with a dash of civilization. In Tuscany itself, there are many sites where one can find remains of Etruscan civilization, places such as Cerveteri, Veii, Tarquinia, Volsinii, Volterra, Vulci and Arezzo.

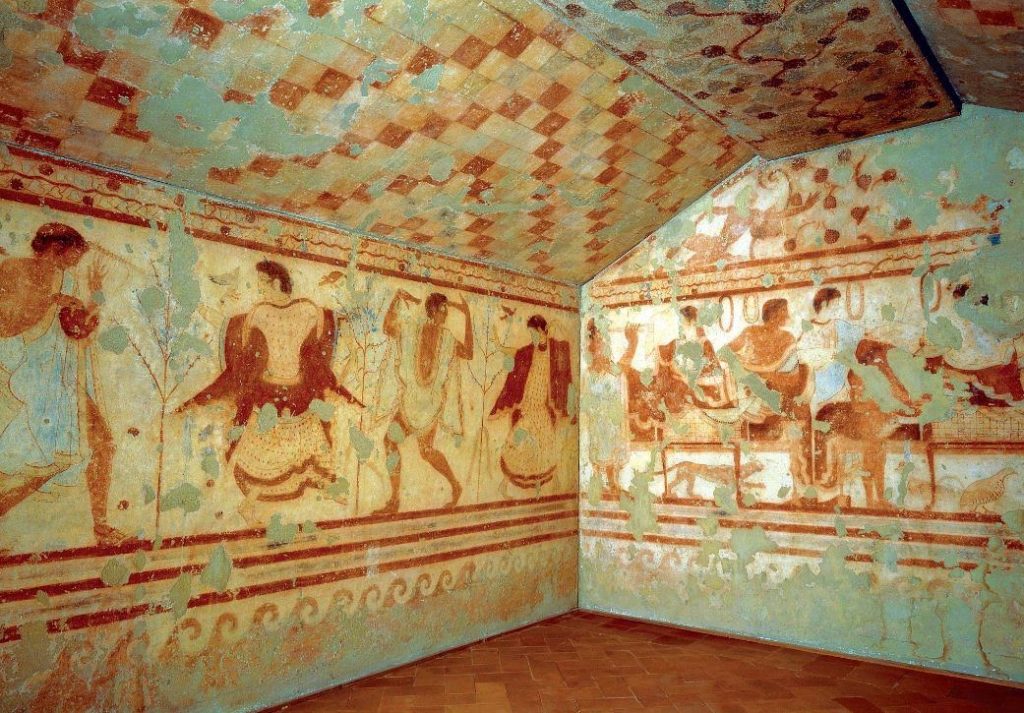

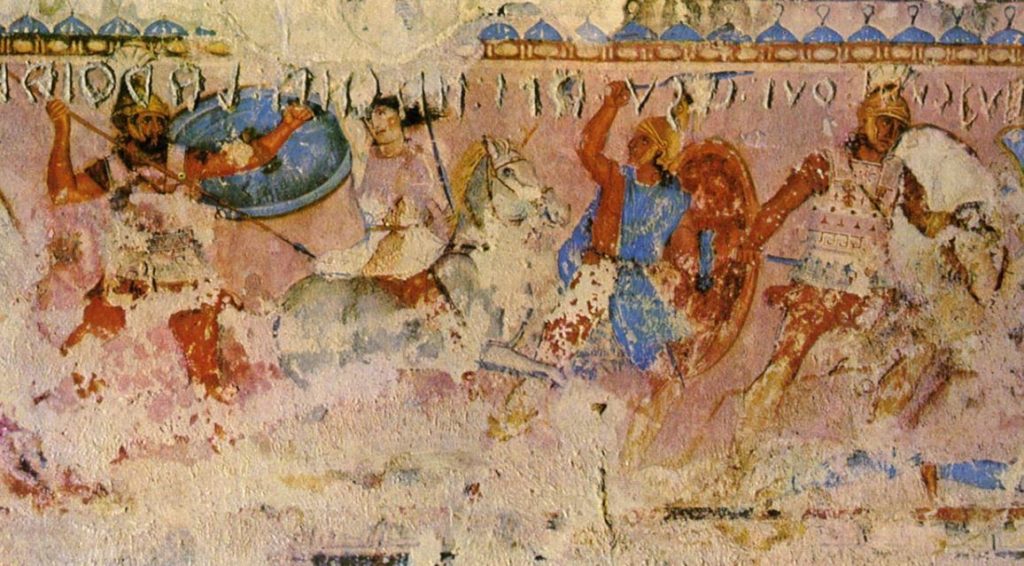

Much of what is known about the Etruscans and their lifestyle comes from their tombs where elaborate paintings of banquets and sporting events such as the Olympics have been found. Many grave goods have been found in the tombs and there is an excellent collection of finds at the Archaeological Museums of Bologna and Florence.

The Etruscans traded a great deal, and so had much contact with the Greeks from other parts of Italy, Sicily and mainland Greece. The walls of the tombs depict chariot races and elaborate banqueting scenes with diners reclining on couches, drinking wine from kraters and being entertained by musicians. The scene is like many an ancient Greek depiction with one marked difference: in Etruscan art, women were shown dining right alongside the men, drinking wine and enjoying conversation. This would have been scandalous to an ancient Greek, as women the other side of the Ionian sea were not permitted to be in attendance at banquets or symposia.

The Etruscans had their own rich culture and this is reflected in much of their bronze artwork and pottery. While some of it resembled ancient Greek art, or indeed was Greek art acquired through trade, much of it is quite unique. An excellent example of this is the famous bronze Chimera of Arezzo on display at the Florence Archaeological Museum.

There is much debate about the origin of the Etruscans in Italy with no consensus yet in sight. Some believe the Etruscans were an indigenous people, others that they came from Lydia in Asia Minor. As far as the Roman scene was concerned, the line of Etruscan kings began circa 616 B.C. with the reign of Tarquin the Elder who was a Corinthian Greek named Lucumo who lived in Tarquinia and married an Etruscan woman named Tanaquil. The two were shunned for a mixed marriage and so moved to the growing centre of Rome where Tarquin became the fifth king of Rome.

The Etruscans were famous for their understanding of augury and prophecy, religious practices which would be widely used in Roman life for hundreds of years. Etruscan augurs would read portents and the will of the gods in animal entrails and organs, and this skill impressed the Romans. The Etruscans not only complemented Roman religious practices, but also helped to improve Roman building practices and it is to them that the Romans owe their talent for building aqueducts and sewers.

At the peak of their power and influence, the Etruscans were the dominant people of central Italy. They were however, never a truly unified nation and, like the Greeks who had influenced them and traded with them, their city-states never stopped fighting amongst themselves. With the Romans growing in strength and skill to the South, and the Celts expanding in the North, the Etruscans were in a superbly unenviable position and could not hold sway for long.

The last Etruscan king of Rome, Tarquin the Proud, who according to Livy took the throne by force and ruled through fear, was narrowly defeated in a series of battles between Etruscan allies and the Romans, led by Lucius Iunius Brutus. Many died on both sides, but Tarquin lived through the day and, though no longer King of Rome, lived out his days in exile in Tusculum. The wheels had been set in motion and Rome had become a Republic.

Of course, when I walked into the cypress-crowned tomb outside Castellina in Chianti years ago, I knew nothing of Etruscan history, nor how fascinating it really is. This short blog post is a tiny scratch on the surface, a mere taste – there is so much more to learn. There are not many books (fiction or non-fiction) on the subject, at least not in English. As far as historical fiction/fantasy, two great reads are Steven Saylor’s Roma, part of which takes place during Rome’s infancy, and the other book is Ursula K. Le Guin’s wonderfully woven tale, Lavinia, which looks at the mythical foundation of Rome with the arrival of Aeneas after the Trojan War.

If you ever find yourself in Italy, I highly recommend the archaeological museums of Florence and Bologna where you can see Etruscan artefacts for yourselves, and it goes without saying that visits to the archaeological sites mentioned are well worth the adventure. Just remember that snakes, as well as tourists, like nothing more than a dark, damp tomb in summer time.

Thank you for reading.

*If anyone has a favourite source for information on the Etruscans, please do share it in the comments below so that everyone can check it out!

Ancient Everyday: Paterfamilias – The Father in Roman Society

It’s been a while since our last Ancient Everyday post, so time to get back to it.

Today, we’re going to look at the father in Roman society, the paterfamilias.

As an example, we are going to use Quintus Metellus Anguis, one of the main characters from the book, Killing the Hydra.

Looking back on the writing of this book, I forget all the years of research that went into it. I take for granted the everyday Roman world I immersed myself in to write it and the rest of the series. It all seems quite normal to me now.

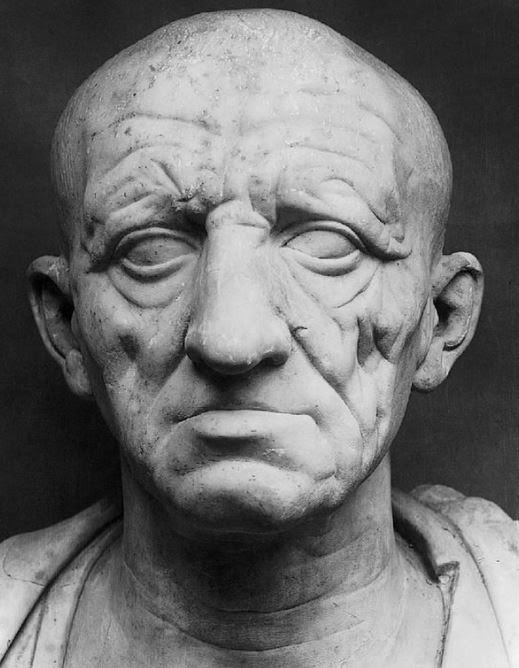

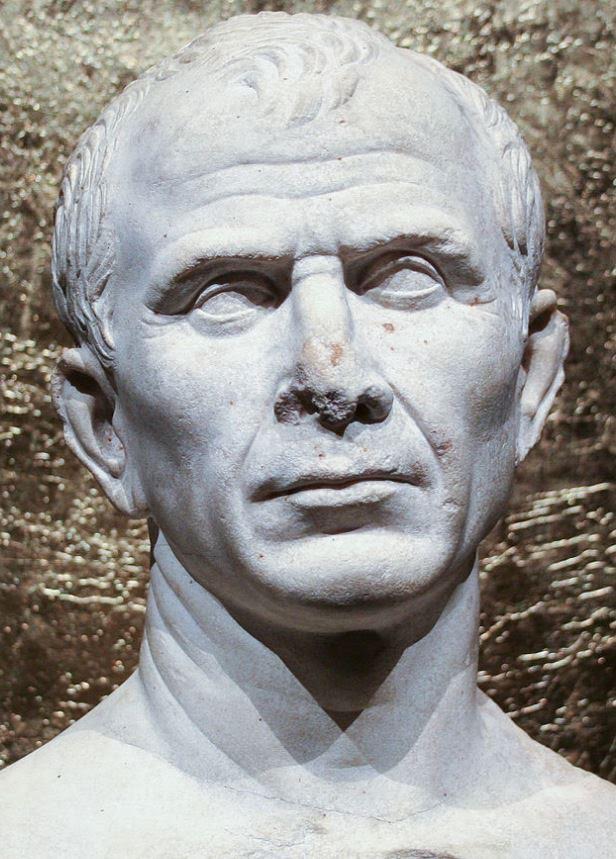

Republican portrait of a man

I’ve spent a lot of time with the characters – the good, the bad, the savage, the honourable, the beautiful, the mysterious etc. etc., but Senator Quintus Metellus Anguis was a difficult person to deal with. However, I’m not sure he would have been out of place in the early Republican era.

Quintus is a spiteful, hard man who is quick to anger and jealous of his son’s (that is, Lucius Metellus Anguis’) successes. He is of a mindset that was born in the very early days of the Republic when there were no emperors, when kings were killed, and when the father held supreme power in the family.

Then again, in some ways, Quintus Metellus could not be more out of place in early 3rd century Rome, the period during which the story takes place.

Imperial Family under Augustus

Let’s take a look at the father in ancient Rome and his role as paterfamilias.

First we should have a look at the word familia. In ancient Rome, a familia did not only include a father, mother and children. The word also referred to other relatives (by blood or adoption), clients, freedmen and all slaves belonging to the family. It included all the family houses, lands and estates and anyone involved with running those holdings.

The Roman familia went far beyond the nuclear family, and the paterfamilias was the head of it all.

Roman Man and his ancestors

During the early days of the Roman Republic, the role of the paterfamilias was largely determined by an unwritten moral and social code called the Mos Maiorum, or the ‘ways of the elders’. These governing rules of private, social and political life in ancient Rome were handed down through the generations. Because these rules were unwritten, they evolved over time. Values and social mores change, as is natural, and successive generations come into their own with ideas different to their predecessors.

The generational differences form a large part of the conflict between Lucius and his father Quintus in both Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra.

Roman Youth – in this case, Marcus Aurelius

Quintus Metellus, as a Republican, is against Emperor Septimius Severus. He has had a vision of his son’s social and political progress since before he was born. He has tried hard all his life to breathe life back into the ancient name of ‘Metellus’, but without success. Now, all the pressure is placed upon his son, Lucius, whom he wants to become a senator of renown after he completes his minimum number of years in the military.

But Lucius has other ideas. He does not want what his father wants. Lucius has found success in the Legions and has been praised and promoted by Emperor Severus, a man he is happy to serve. Unlike many equestrian youths, Lucius Metellus Anguis is not interested in pursuing a political career. He wants to be a career officer in Rome’s Legions – something that causes his father no end of embarrassment and frustration. In his opinion, it is not the way to further the family name and better their fortunes.

In the early days of the Republic, Lucius would have had to do as his paterfamilias dictated. There would have been no choice in the matter, no influence from his mother or older sister to help his cause. The paterfamilias’ word was law within the familia.

In ancient Rome, the paterfamilias had to be a Roman citizen. He was responsible for the familia’s well-being and reputation, its legal and moral propriety. The paterfamilias even had duties to the household gods.

And this is where Quintus Metellus fails. He has lost faith in the gods that have watched over them. In fact, he fears them and their apparent favour of his son. Quintus clings to the archaic role of the paterfamilias like a dictator with power of life and death over the members of his familia. He forgets that the paterfamilias’ role is also to protect his familia within the current world they live in, and to honour their ancestors and their gods through his behaviour, his example.

This is where Lucius fills the void in duties neglected by his father.

But it is never as easy as that. The Empire is large, and most men are susceptible to corruption. Lucius fights for honour and goodness in a world that has no qualms about dismissing honour, virtue and family in the interests of greed and political advancement.

Quintus Metellus is the paterfamilias of their branch of the Metellus gens, but his own shortcomings and archaic notions are at complete odds with his son and the times they live in.

It’s always interesting to compare previous ages and practices with those of our own. Certainly the role of the father has changed over the centuries, though it varies from family to family and culture to culture.

Roman husband, wife and children

Fortuna smiled on me with my own father who, thankfully, bore no resemblance to Quintus Metellus. But it was interesting to write such a character as Quintus, to explore his relationship with Lucius and the rest of the familia.

By the 3rd century A.D. the paterfamilias’ power of life and death over his family was restricted, the practice all but dead.

But old habits and ideas die hard, and for Quintus Metellus there are other ways to kill a member of your familia and maintain your power as paterfamilias.

Thank you for reading.

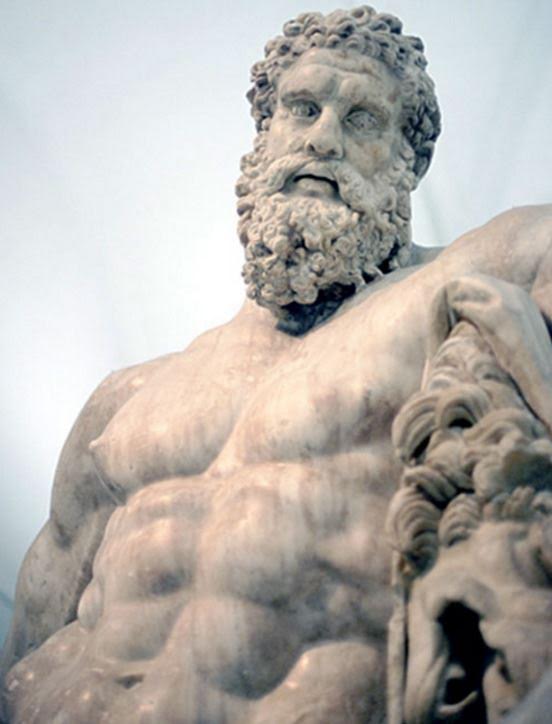

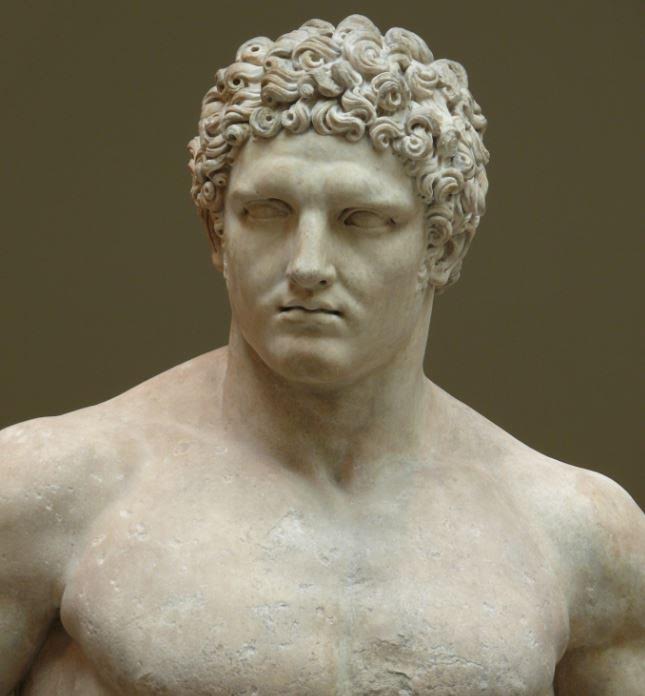

The Tragedy of Herakles

Alas! alas! lament, O city; the son of Zeus, thy fairest bloom, is being cut down. Woe is thee, Hellas! that wilt cast from thee thy benefactor, and destroy him as he madly, wildly dances where no pipe is heard.

She is mounted on her car, the queen of sorrow and sighing, and is goading on her steeds, as if for outrage, the Gorgon child of Night, with hundred hissing serpent-heads, Madness of the flashing eyes. Soon hath the god changed his good fortune; soon will his children breathe their last, slain by a father’s hand. (Euripides – Herakles)

In Part I of this series on Herakles, we looked at his triumphs, the Twelve Labours that set him down on the papyrus pages of ancient history as the greatest hero. He was a man of great strength, appetites, perseverance, and emotion. He traveled the world achieving feats that would have defeated any other man of his time.

The tales of Herakles’ heroics have inspired for centuries.

But, as with all tales from ancient Greece, triumph and tragedy go arm in arm in the hero’s life.

The tragedy of Herakles’ life actually began, as mentioned in Part I, before his twelve labours, when he was driven mad by Hera and ended up killing his wife, Megara, and their children.

Ah me! why do I spare my own life when I have taken that of my dear children? Shall I not hasten to leap from some sheer rock, or aim the sword against my heart and avenge my children’s blood, or burn my body in the fire and so avert from my life the infamy which now awaits me? (Euripides – Herakles)

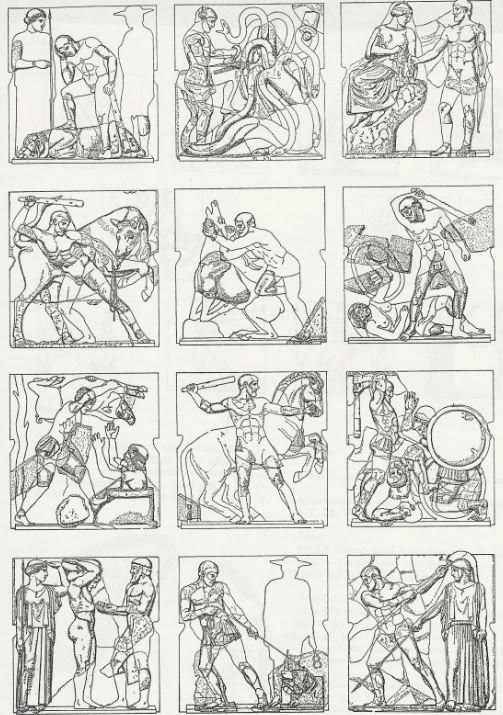

Metopes of the 12 Labours adorning the Temple of Zeus at ancient Olympia

The twelve labours were a part of his atonement for this horrifying crime.

One would have thought that with the Labours he had paid the price, but that would be too easy. As we shall see in this brief post, Herakles would be made to suffer and live a life of rage and pain till the end of his days. There would be no sitting on his laurels.

As the following passage shows, even in the fiery realm of Hades, Herakles’ shade is dark and menacing, someone even the dead are afraid of:

Next after him I observed the mighty Herakles – his wraith, that is to say… From the dead around him there arose a clamour like the noise of wild fowl taking off in alarm. He looked like black night, and with his naked bow in hand and an arrow on the string he glanced ferociously this way and that as though about to shoot… (Homer – The Odyssey)

Herakles is often known as ‘Alexikakos’, the ‘averter of evil’, but this proved impossible when it came to himself.

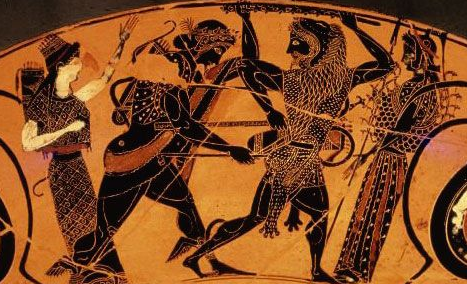

Apollo and Herakles fighting over the Delphic Tripod

He was often helping others, such as when in Hades, he found Theseus, another hero, in his punishment, and raised him up to be free back on Earth.

But did others often help Herakles?

Sometimes. During his labours, he did receive aid from Athena, Atlas, Helios, and from his cousin, Iolaus, but most of the time, he had to go it alone.

After the Twelve Labours, Herakles seems to have become a sort of fallen hero.

When he kills Iphitus, the son of Eurytus who had refused to give the hero the hand of his daughter, Iole, he becomes diseased because of the murder; this is a punishment from the Gods.

Herakles goes to the Oracle at Delphi, but the Oracle refuses to answer him this time. In a rage, Herakles attempts to steel the sacred tripod which Apollo tries to take back.

Herakles and Omphale

Zeus steps in to stop the quarrel between his two sons, and the Oracle complies in giving Herakles an answer; he must sell himself into slavery for three years.

He is ‘bought’ by Omphale, a Queen of Lydia. It is during this time of servitude that Herakles joins the Argonauts, one of the most famous crews in history, in their search for the Golden Fleece. Even here, the hero is not allowed to be a part of the Argonauts’ success as he is left behind in Mysia to search for his friend, Hylas, who was abducted by water Nymphs.

The Argonauts

Once his service to Omphale was settled, Herakles seems to have set out on a fit of vengeance to settle some old debts.

He raised an army with Telamon and sailed to Troy where he captured the city and killed King Laomedon. He also killed all the Trojan princes too, except Priam.

Herakles about to kill Laomedon

Other acts of revenge included killing King Augeas of Ellis, and his sons, who had refused to pay up for the cleaning of his stables.

Herakles then marched to Pylos to face Neleus who had refused to purify him of the murder of Iphitus who was a guest of Herakles’ in Tyrins at the time. Herakles slew Neleus and all twelve of his sons except Nestor who was away at the time, and who would be a part of the later Trojan War.

On top of all this, Hera did not relent in her persecution of Herakles. She sent storms to pursue the hero, but it is at this point that Zeus finally says enough is enough. The king of the gods suspends Hera from Mt. Olympus with anvils tied to her feet.

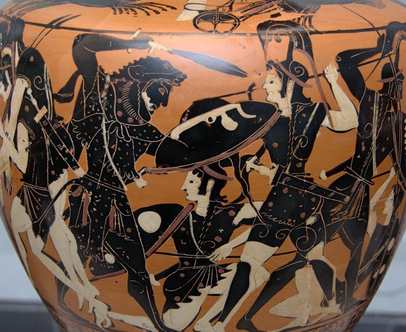

Battle of the Gods and Giants – Siphnian Treasury at Delphi)

Then the Gods themselves need Herakles’ help at Phlegrae, in Thrace. The Battle of the Gods and Giants is one of the most widely depicted events in ancient Greek art. It is here that Herakles played a key role in aiding the Gods to victory.

But, exhaustingly, sadly, that is not the end for Herakles. It is not time to rest. He continues with his acts of vengeance, among them the sacking of Sparta, and the killing of Hippocoon and all his sons.

Our fallen hero has much blood on his hands at this point, but finally, after so much turmoil, he finds a measure of happiness in Calydon where he marries Deianeira, the daughter of King Oeneus. She is also the sister of Meleager, whom Herakles had spoken with in Hades on his twelfth labour.

Herakles and Deianeira

While in Calydon, Herakles helps his father-in-law to defeat his enemies. He and Deianeira have several children together. She is beautiful, virtuous, and loves her husband dearly.

But the idyllic time is short-lived. At one point, Herakles accidentally kills King Oeneus’ cup bearer, and so he, Deianeira, and their children are forced to leave Calydon. They settle in Trachis.

On one part of their journey, they must cross the river Evenus. While he is crossing the river, it seems that Herakles entrusts his wife to the centaur, Nessus, who tries to rape her.

Herakles’ rage takes over and he kills Nessus with one of his arrows dipped in the blood of the Hydra.

As Nessus lays dying, he whispers to Deianeira that his own blood is a powerful love charm, and that she should take some and keep it hidden if ever she needed it.

Deianeira saves some of the centaur’s blood.

While in Trachis, Herakles helps his host King Ceyx, to defeat his enemies. It seems that kings were happy to host Herakles if he helped them to defeat their foes. Herakles then helped Aegiaius to fight and defeat the Lapiths, and in that conflict, he killed Cycnus, the son of Ares, in single combat, as well as wounding Ares himself.

Iole

Bent on vengeance once more, Herakles raises an army and marches against Eurytus who had refused him the hand of Iole. Herakles takes the young girl as his concubine and, along with many prisoners, brings her back to Trachis.

The springs of sorrow are unbound,

And such an agony disclose,

As never from the hands of foes

To afflict the life of Heracles was found.

O dark with battle-stains, world-champion spear,

That from Oechalia’s highland leddest then

This bride that followed swiftly in thy train,

How fatally overshadowing was thy fear!

But these wild sorrows all too clearly come

From Love’s dread minister, disguised and dumb.

(Sophocles – The Women of Trachis)

Deianeira mourning

Deianeira realizes that her husband loves the quiet, beautiful Iole, and decides to use the supposed ‘love-charm’ of the centaur’s blood.

At this time, Herakles was in Euboea sacrificing to Zeus for his many triumphs over his enemies. He sent to Deianeira for his finest robe for the ceremonies. With this act of piety, Herakles seals his doom, for Deianeira smears the blood of Nessus on the robe thinking that it will make Herakles love her again.

The blood begins to eat into Herakles’ flesh like acid, killing him slowly.

When Deianeira hears from their son, Hyllus, what she has done, she kills herself in despair. The nurse to the Chorus:

When all alone she had gone within the gate,

And passing through the court beheld her boy

Spreading the couch that should receive his sire,

Ere he returned to meet him,—out of sight

She hid herself, and fell at the altar’s foot,

And loudly cried that she was left forlorn;

And, taking in her touch each household thing

That formerly she used, poor lady, wept

O’er all; and then went ranging through the rooms,

Where, if there caught her eye the well-loved form

Of any of her household, she would gaze

And weep aloud, accusing her own fate

And her abandoned lot, childless henceforth!

When this was ended, suddenly I see her

Fly to the hero’s room of genial rest.

With unsuspected gaze o’ershadowed near,

I watched, and saw her casting on the bed

The finest sheets of all. When that was done,

She leapt upon the couch where they had lain

And sat there in the midst. And the hot flood

Burst from her eyes before she spake:—‘Farewell,

My bridal bed, for never more shalt thou

Give me the comfort I have known thee give.’

Then with tight fingers she undid her robe,

Where the brooch lay before the breast, and bared

All her left arm and side. I, with what speed

Strength ministered, ran forth to tell her son

The act she was preparing. But meanwhile,

Ere we could come again, the fatal blow

Fell, and we saw the wound. And he, her boy,

Seeing, wept aloud.

(Sophocles – The Women of Trachis)

Back on Euboea, Herakles, in great pain, knows it is his time and has a pyre built for himself on Mount Oeta. He climbs up onto the pyre and asks for help lighting it.

But no one will help the hero.

Poor Herakles…

Finally, a passing shepherd by the name of Poeas, who is looking for his sheep, decides to help Herakles. As a gift, Herakles gives Poeas his great bow and arrows.

Now my end is near, the last cessation of my woe. (Sophocles – The Women of Trachis)

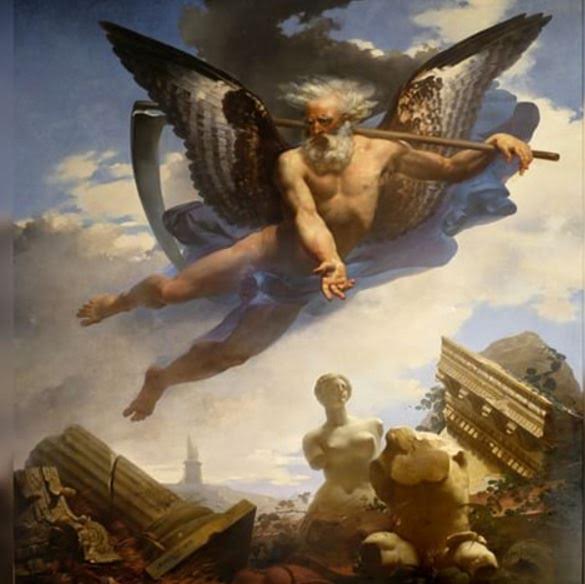

As the pyre burned, thunder raged in the sky, and Herakles is taken to Mt. Olympus to join the ranks of the Immortals.

Apotheosis of Herakles (Francois Lemoyne)

After all the pain and hatred, he and Hera are finally reconciled, and he is married to Hebe, the Goddess of Youth.

As an eternal monument to his long-suffering son, Zeus sets Herakles in the stars where he kneels to this day.

Herakles Constellation

Before I had written these posts, I had never looked at the triumph and tragedy of Herakles as a whole. I had grabbed at bits and pieces of his life for inspiration, for short story, for entertainment, like a literary carrion crow.

But the epic life and journey of Herakles, as a single life lived, leaves me breathless and shaking with emotion.

After his initial madness and the slaying of Megara and his children, death and the burning halls of Hades might have been an easier path than the one he took.

I don’t think immortality was ever Herakles’ goal.

How might Herakles have felt, remembered as he is after his apotheosis?

To have travelled so far, to have lived, and loved, and fought, and conquered, and suffered enough for many lifetimes…is a thing unimaginable to this mere mortal as he types these words.

Herakles’ life is not only the stuff of legend, it is the essence of art, and poetry, of lesson, and of inspiration.

As Theseus, in Euripides’ play, says to Herakles when he finds his friend mourning his dead wife and children:

Yea, even the strong are o’erthrown by misfortunes.

Thank you for reading.

If you would like to read more, follow the links below to get free downloads of the following works:

The Women of Traches and Philoctetes by Sophocles

Alcestis and Heracles by Euripides

For coherent histories of Herakles’ life you can view the works of both Apollodorus and Diodorus Siculus on theoi.com

The Triumphs of Herakles

Some of the most timeless stories in western literature are about the heroes of ancient Greece.

For millennia people have been inspired by Perseus, Jason and the Argonauts, Theseus, Achilles and Odysseus. Many an ancient king and warrior has tried to emulate the actions and personae of these heroes, and even claimed descent from them.

Far and away, the greatest hero of all was Herakles.

There are so many stories related to Herakles (‘Hercules’ of you were Roman) in mythology that it’s impossible to cover all of them in a simple blog post. A book would be required for that.

So, this post is going to be the first in a two-part series on the hero. There are countless triumphant deeds associated with Herakles, but for our purposes here, I’m going to cover the most famous of all – The Twelve Labours.

The Twelve Labours of Herakles have been the subject of art, sculpture and song for ages. Their portrayal decorated the ancient world from the images on vases to the metopes on the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. In our modern age, we’ve seen him in comics, television shows, and movies.

Aerial view Tiryns

But who was Herakles? Where did he come from?

Herakles was born in the city of Thebes. He was the son of Zeus who begat him on Alcmene, a granddaughter of Perseus and Andromeda. Zeus came to her in the guise of her mortal husband, Amphitryon, and so Herakles was born.

From the beginning, Herakles showed that he was not a ‘normal’ person. Out of jealousy, Hera, Queen of the Gods and wife of Zeus, sent two snakes to kill the baby Herakles in his cot. Herakles strangled the snakes with his bare baby hands.

When he was 18 years of age, Herakles began to really make a name for himself by slaying a lion on the slopes of Mount Cithaeron after hunting it for fifty days. During that time, he stayed with the king of Thespiae who was so impressed with the youth that he had him beget children on all fifty of his daughters.

Herakles was a man of extreme prowess, deeds, emotion and appetites.

King Creon of Thebes rewarded Herakles for helping him against his enemy, Erginus, king of the Minyans by giving him the hand of his daughter Megara, with whom the hero had several children.

This is where things sour for the young hero. After all, this is a Greek story, and tragedy is never far behind to bring even the mightiest of heroes back to Earth.

Temple of Apollo at Delphi

Hera stepped in to afflict Herakles with madness, causing him to kill his wife and children. When his sanity returned, he was overcome with grief and went to the Oracle at Delphi for advice.

The Oracle told him to go to Tyrins and serve its king, Eurystheus, for twelve years, as punishment for his brutal crime. He had to complete all tasks set for him by the king, and this is the origin of The Twelve Labours.

It’s curious that the name ‘Herakles’ means ‘Glory of Hera’, since she persecuted him so much throughout his life. Then again, perhaps as Hera is the root cause of his Labours, his triumphs reflect on her?

I – The Nemean Lion

This first labour is probably his most famous, and takes us to the ancient land of the Argolid peninsula. The lion that was terrorizing the hills about Nemea had skin that was impenetrable to weapons and so Herakles, when he faced it, choked it to death with his brute strength and then used the claws to skin it. It’s this skin, which he used as a hooded cloak, that the hero became known for in art. If you see someone with a lion’s head on their own, it’s likely Herakles, or someone trying to emulate him.

Region of Nemea

As a side note, Nemea was thereafter the site of the Nemean Games, one of the four sacred games of the ancient world, which also included the Isthmian Games, the Pythian Games, and the Olympic Games. You can read more about ancient Nemea by CLICKING HERE.

II – The Lernean Hydra

When he faced the Hydra in the Peloponnesian swamps of Lerna, it’s a good thing that Herakles brought along his nephew and companion, Iolaus. Facing the monster, he discovered that when he cut one head off, two more grew back in its place. And so, after each head was cut, Iolaus would cauterize the stump before it could grow again. When the Hydra was dead, Herakles dipped his arrows in the blood which was poison, even to Immortals. These arrows would come in useful in later episodes of the hero’s life.

Heracles fighting the Hydra

III – The Ceryneian Hind

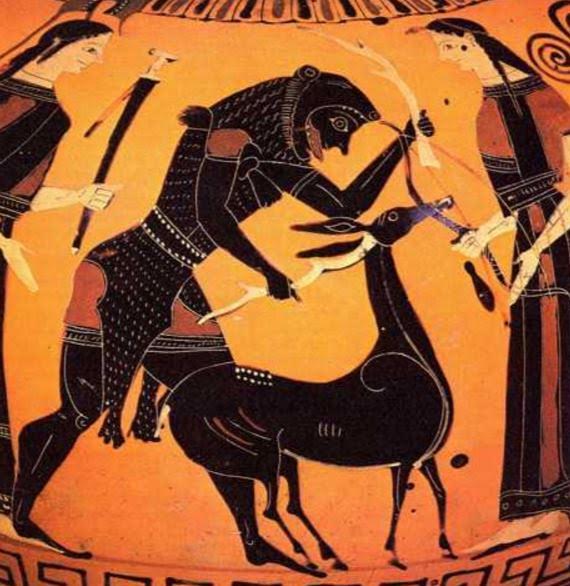

Eurystheus, this time, thought he would set Herakles against Artemis with this third labour by telling him to capture a deer with golden horns that was sacred to the goddess. But Herakles pursued the hind for a whole year until he finally captured it and brought it before Eurystheus who, by this time, was always hiding in a jar whenever his cousin would return. The hind was allowed to go once it was brought before the king and so Herakles was able to avoid Artemis’ wrath.

The Cyreneian Hind

IV – The Erymanthian Boar

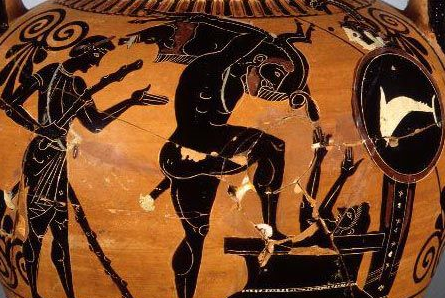

Herakles delivers the Erymanthian Boar to Eurystheus

Around Psophis, in the Arcadian region of the Peloponnese, a massive boar had been giving the locals trouble and so Herakles was sent to capture it. He did so by pursuing it through deep snow in the mountains until it was so exhausted that he was able to capture it. Such a massive specimen would have made quite a sacrificial feast!

V – The Stables of Augeas

Athena aiding Herakles to clean the Augean Stables

Augeas was the King of Elis, and he had a cattle stable that had never been mucked out, EVER! In this case, it was not a monster that terrorized the locals, but rather the monumental stench. In this very different labour, Herakles was told he had to clean out the stables. So, what did he do? What all heroes would do, he diverted the rivers Alpheius and Peneius so that they flowed through the stables and washed the titanic stink away. It’s no wonder the land thereabouts is so fertile!

VI – The Stymphalian Birds

In Stymphalia, there were flocks of man-eating birds with bronze beaks that infested the woods around the Lake of Stymphalus, again in Arcadia. Herakles was told he had to get them out. So, he scared them all from their hiding places and then shot them down with his great bow. No more birds.

Lake Stymphalos

VII – The Cretan Bull

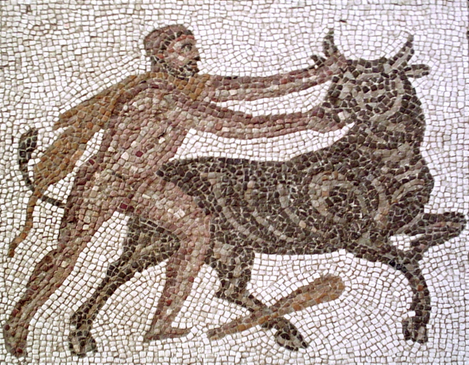

For his seventh labour, Herakles had to leave the Peloponnese for the Island of Crete to capture and bring back the Cretan Bull. This was no ordinary bull. This was the bull that Poseidon sent to Crete for King Minos to sacrifice. When Minos refused, Poseidon made his wife, Pasiphae fall in love with it and from that union was born the terror that was to become the Minotaur. The Cretan Bull rampaged all over Crete until Herakles arrived, wrestled it to the ground, and brought it back to Greece. The hero’s friend, Theseus, would come back to Crete years later to take care of the Minotaur.

The Cretan Bull

VIII – The Mares of Diomedes

Once more, Herakles was forced to deal with another group of man-eating animals. But this time they were not birds, but rather horses! The mares of Diomedes were in Thrace.

When Herakles arrived in that northern kingdom, he had a run-in with Diomedes himself and so, to tame the horses, Herakles fed them their own master. After that, the mares followed him back to Eurystheus.

The man-eating Mares of Diomedes

IX – The Girdle of Hippolyte

Herakles fighting the Amazons

Near the River Thermodon, just off the Black Sea, Herakles and his followers, including Theseus, went to the Amazons and their Queen, Hippolyte. The story goes that Herakles just asked this lovely daughter of Ares for her girdle, or belt, and she said ‘Yes’. Hera decided to step in and whispered to the rest of the Amazons that their queen was being abducted.

The Amazons attacked Herakles and his men who fought back, and in the bloody engagement, Hippolyte herself was killed. Herakles managed to get the girdle, but the cost of this labour was indeed heavy.

The River Thermodon

X – The Cattle of Geryon

The tenth labour is a sort of epic cattle raid. Herakles was told he had to bring back the red cattle of the three-bodied giant, Geryon, from the Island of Erytheia which was far, far to the west. This took the hero on a long journey into the Atlantic. On his way, he set up the Pillars of Hercules to mark his way.

Herakles driving off the Cattle of Geryon

But Herakles began to grow weary with the heat, and so Helios, God of the Sun, lent Herakles his great golden bowl or boat so that he could sail the rest of the way to Erytheia. Herakles succeeded in raiding the cattle and sailed in Helios’ boat back to Spain. From Spain he travelled to Greece and had many adventures on this mythic cattle drive.

There is a whole list of adventures he had on his way home, but the one I would like to highlight brings him in touch with the Romans. When Herakles arrived in Rome he came into conflict with a monster named Cacus after the beast killed some of the cattle. Herakles killed Cacus in what must have been a great battle of strength.

Temple of Hercules, Rome (Wikimedia Commons)

It’s interesting that in Rome, there are some steps leading off of the Palatine Hill called the Steps of Cacus which is where the monster is said to have lain in wait for passers-by. In the Forum Boarium, or cattle market, near the banks of the Tiber, there is a round Tholos temple dedicated to Hercules, commemorating the hero’s time in Rome.

XI – The Golden Apples of Hesperides

Hesperia was the garden of the gods, and Herakles must have been exhausted when he discovered that he had to go back to the Atlantic. Some believe Hesperia was located on the Atlantic side of the North African coast. The garden was said to be beyond the sunset, where Atlas, the Titan, was holding up the sky.

The Golden Apples of Hesperides

The labour was to pick the golden apples that were guarded by a giant snake. In some stories, Herakles asks Atlas to pick the apples for him while he holds the heavens in his stead. In others, Herakles picks the apples himself and kills the serpent.

XII – Cerberus

There is one archetype that is common to most hero stories, and that is the journey to the Underworld. And this is where Herakles must go in his final labour, to bring the three-headed hound of Hades back to Eurystheus.

Herakles and Cerberus

To get to the Underworld, Herakles gets help from the god Hermes, who travelled there regularly. Supposedly, they entered through the gate at Taenarum, in the southern Peloponnese.

There is a fascinating episode when they arrive in Hades’ realm. The shades of the dead flee from Herakles who wounds Hades himself with one of his poison arrows. The only shades who do not flee are Meleager, famed for bringing down the great Calydonian Boar, and Medusa, the Gorgon slain by Perseus.

Gate to Hades at Taenarum

Herakles drew his sword against Medusa, but Hermes told him to leave her be. But Meleager told the hero his sad tale. Herakles, inspired by Meleager, said that he would marry the sister of such a noble man. And so, the shade of Meleager named his sister, Deianaira, to be Herakles’ wife. This at the end of his long penance for killing his family. Was it a new beginning?

Hades told Herakles that he could take Cerberus if he could bring him to heel without using his weapons. In true Heraclean fashion, he wrestled the hell hound and then brought it to Eurystheus.

Afterward, Hades got his dog back.

Herakles resting after his Labours

The Labours of Herakles are not just adventure stories. They are stories of atonement, of courage, of strength of mind and body. Over and over, the hero is taken to extremes until he attains his final triumph, and his debt is paid.

But this is a Greek story. There is no celebration. For laurels dry out on the brow of even the greatest of heroes.

There is much more to Herakles’ story. I don’t think I’ll ever tire of these tales.

Next week, in the second part of this series, we are going to be looking at the tragedy of Herakles.

Thank you for reading, and until then, stay Strong!

Florentia: The Roman origins of Florence

We’re changing pace for this next blog post, leaving the world of Roman Britain behind for the moment.

Over the holiday season, I managed to watch a bit of television – something that I don’t really do that often.

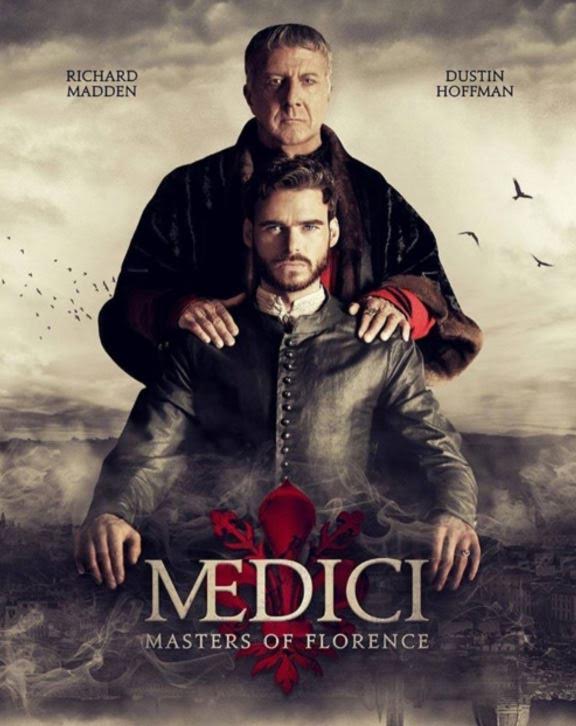

Like most people nowadays, I headed over to Netflix to see if anything caught my eye, and sure enough, there was a title that promised some great historical drama: MEDICI.

The show was only eight episodes, and certainly called to my love of history, Tuscany, and Italy in general. So, I sat down to watch.

I was not disappointed.

If you want a peak at Florence and the era that really gave rise to the Italian Renaissance, this is something you should watch.

Tuscan landscape

I love Florence, and have been there a couple of times.

It’s one of the most beautiful, culturally-rich cities I’ve seen, and I would go back there in a heartbeat.

If you’ve been there, you’ll know what I mean when I say that this city is for roaming and enjoying. From the Duomo and Baptistery, to the Ponte Vecchio, the Piazza della Signoria and the Palazzo Vecchio, to the hallowed halls of the Uffizi Gallery where countless masterpieces hang, there is so much to see and do (and eat!) in this beacon of art and culture on the banks of the Arno.

Piazza della Signoria (by Giuseppe Zocchi)

When anyone thinks of Florence, they think of late medieval and Renaissance art and architecture, of the greats of history such as Dante, Da Vinci, Machiavelli, the Medici and many more.

When one thinks of Florence, the Roman Empire is not usually the first thing that comes to mind.

The truth is that Florence was originally established as a Roman camp. It was called ‘Florentia’, and beneath the façade of Renaissance grandeur that we see today, this city has Roman roots.

Today, we’re going to take a brief look at the Roman origins of Florentia.

Julius Caesar

Before the Romans overtook this land, the Etruscans ruled here, and they had established a centre at Fiesole, up the hill a short distance from the Arno River.

The Roman settlement of Florentia was established, most agree, by Julius Caesar around 59 B.C. as a military camp intended to guard the ford where the Via Cassia, the main road through Etruria, crossed the river.

It was just prior to this that Catiline led a rebellion against the Republic, and it seems that perhaps he, and many of his supporters holed up in nearby Fiesole.

Around 60 B.C., Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer, one of Rome’s consuls at the time, marched out to meet Catiline’s forces.

Roman ruins at Fiesole

Now, here is where the story gets a bit blurry.

There appears to be some confusion around the origins of the name, ‘Florentia’.

Some believe that the word stems from ‘fluente’ which may refer to the flowing of the Arno river itself.

However, there is another, more romantic tale regarding the foundation of Florentia.

There is a story that accompanying Metellus against Catiline’s forces in Fiesole was a praetor or other high-ranking person named ‘Fiorinus’ who led several actions against Catiline and his conspirators.

This Fiorinus apparently fought very bravely, but was killed in an attack on the Roman camp along the Arno.

Why was this man, Fiorinus, important?

Well, some believe that Julius Caesar, who joined the battle against Catiline at Fiesole shortly thereafter, named Florentia after Fiorinus.

Here, Machiavelli writes about the two different theories about the origins of the name:

There are various opinions concerning the derivation of the word Florentia. Some suppose it to come from Florinus [Fiorinus], one of the principal persons of the colony; others think it was originally not Florentia, but Fluentia, and suppose the word derived from fluente, or flowing of the Arno… I think that, however derived, the name was always Florentia, and that whatever the origin might be, it occurred under the Roman empire, and began to be noticed by writers in the times of the first emperors.

(Niccolo Machiavelli, History of Florence and the Affairs of Italy)

The Discovery of the Body of Catiline (1871) Alcide S … allery of Modern Art, Florence) Wikimedia Commons

As with many ancient tales, it’s difficult to ascertain the truth.

The important thing, and that which is more generally agreed upon, is that Florentia was established as a camp by Julius Caesar, who later made it a colonia for veterans of his legions.

When we walk around Florence today, it is clearly a medieval and Renaissance city. However, if you know where to look, you can see the remains of Colonia Florentia.

Main roads of Roman Florentia

In the image above, you can see the main Roman roads on today’s Florentine streets.

The main north-south street of Florentia, the cardo maximus, followed the line of the Via Roma today. On the east-west axis, the former decumanus maximus ran the length of the current Via degli Speziali, and the Via degli Strozzi.

Like all thriving Roman settlements, the beating heart of the city was the forum, and Florentia’s was located in what is now the Piazza della Republica.

Piazza della Repubblica – the Forum of Florentia (Wikimedia Commons)

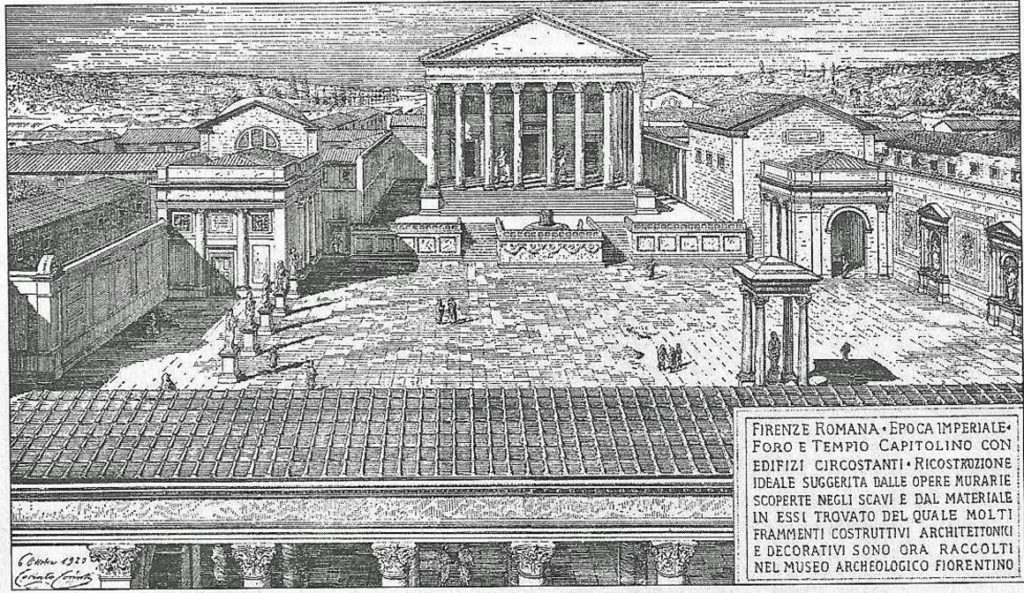

Apart from being the commercial centre of Florentia, the forum was also the administrative and religious centre of the colonia. There was no antique carousel, as there is today, but there was a temple to Mars, as well as a temple to the Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva.

The curia itself, which was also located in the forum, was where the town council, made up of decurions, met to discuss the business of the colonia. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the governing body of Florence, known as the Signoria instead of the Curia, met in the Palazzo Vecchio, located in the current Piazza della Signoria.

Artist impression of the Forum of Florentia

Archaeologists, over time, have discovered other Roman structures beneath the streets of this city, ghostly shades of Florentia’s past.

There were Roman baths located outside the south wall of the original fort along the current Via delle Terme. After all, what Roman settlement did not have a bath?

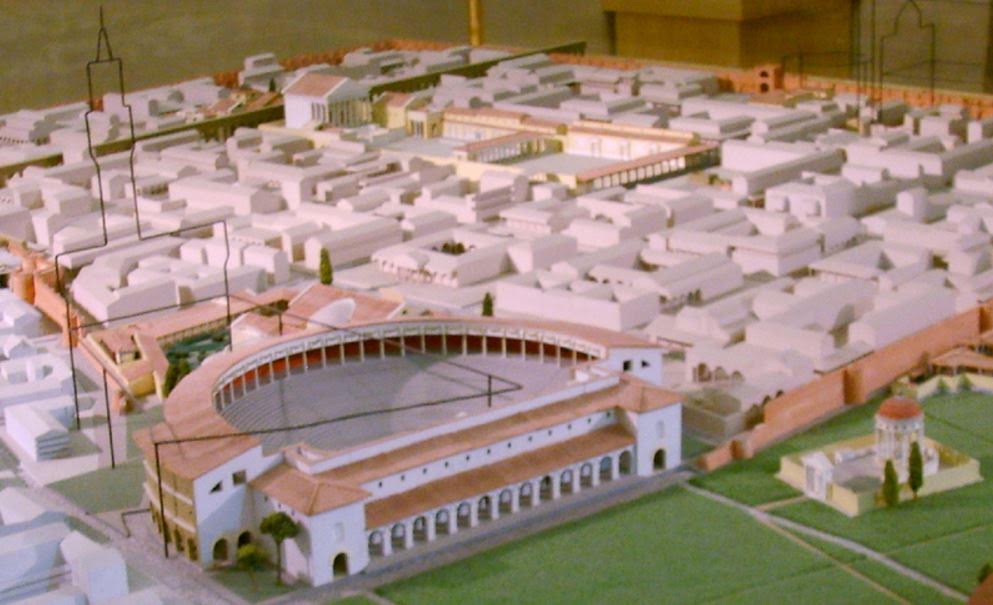

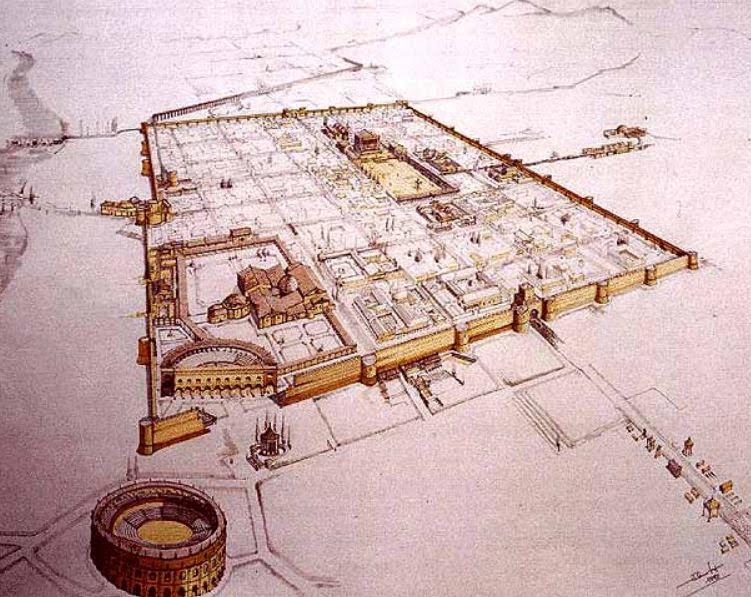

Model of Roman Florence (from the southeast)

The same goes for a theatre.

As if echoing the artistic future of this great city, Florentia had an 8-10 thousand seat theatre in the southwest precinct of the colonia. The Palazzo Vecchio is partially built over top of this.

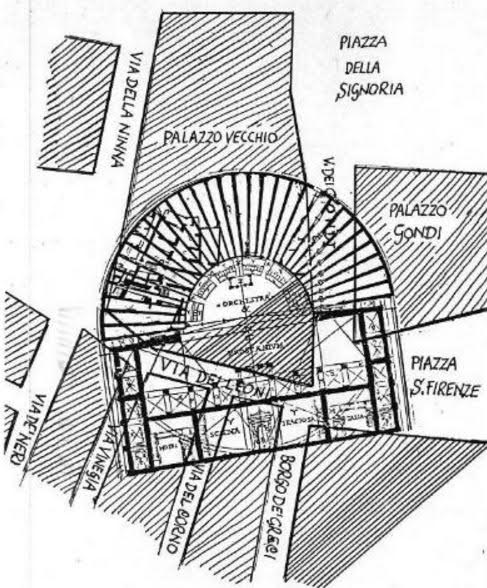

Reconstruction of Florentia’s Theatre

If you walk behind the Palazzo Vecchio today, and cross Vie dei Leoni, you will find yourself outside the line of the original Roman walls.

Along Borgo dei Greci lies Piazza san Firenze where, during the Roman period, there stood a temple of Isis, the Egyptian goddess whose cult had become quite popular across the Roman Empire.

Continue on Borgo dei Greci to the curve of Via Bentacordi and you will find yourself on the site of the amphitheatre of Florentia, just near the current Piazza Santa Croce.

The amphitheatre was, of course, where the troops would have drilled and paraded, and the populace would have enjoyed gladiatorial combats and other entertainments popular in the Roman world.

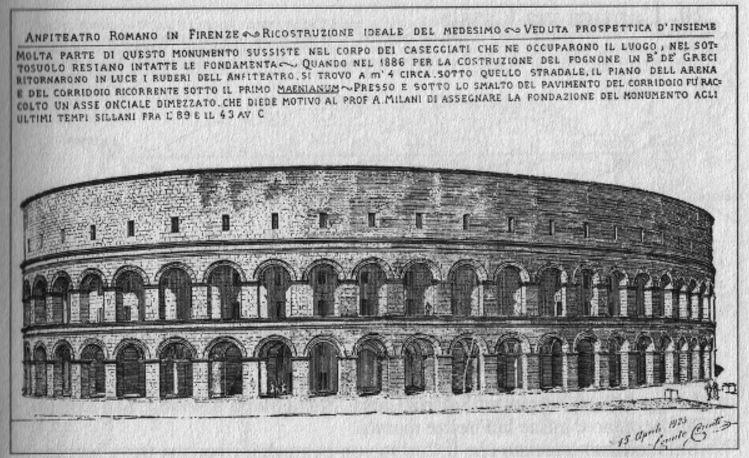

Reconstruction of Florentia’s Amphitheatre

Sadly, most of Roman Florentia is hidden from our eyes, but there are a few other places where the Roman past is hinted at.

For example, just before the Bargello, outside what was the ancient east wall, there is a brass half-circle in the street that marks the foundation of a Roman watch tower. Archaeologists have also found the remains of cloth dying vats which indicate that Florence’s pre-eminence as a textile-producing centre may have originated much earlier than in the Middle Ages.

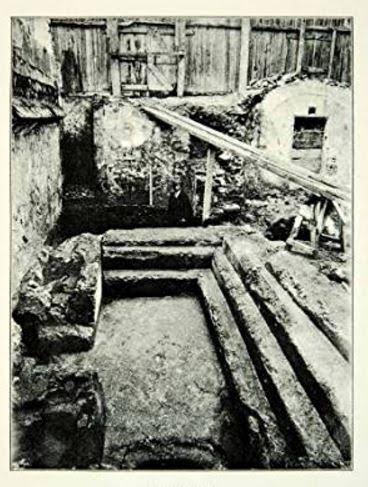

Remains of a frigidarium in Florance

There are other remains dotted around the city too – the remains of baths, private villas and homes – but most are inaccessible, or require permission from property or business owners to view.

Beneath Florence’s most prominent monument, Santa Maria del Fiore, or the ‘Duomo’ as it is known, was the site of an ancient Roman temple and other buildings (both Roman and early Christian). These can be viewed in the crypt of the Duomo, which was opened to the public, I believe, in 2014. Sadly, that was after I had visited!

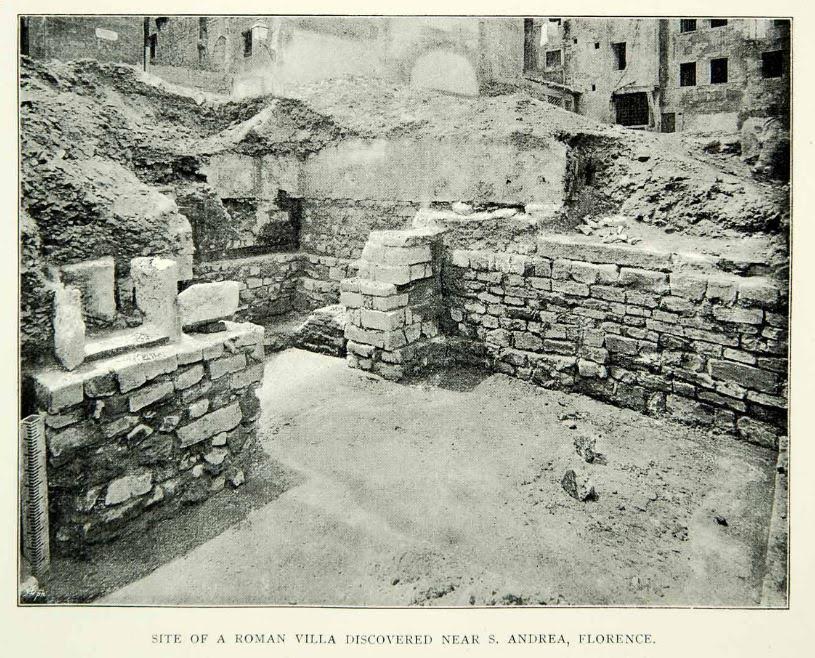

Part of a Roman Villa near San Andrea, Florence

And finally, across from the entrance to the Duomo, is the famous Baptistery of San Giovanni, which was built in the 11th century. This magnificent, octagonal building is one of the oldest standing buildings in Florence today, and it is believed that much of the marble facing used to decorate the walls of the Baptistery was taken from the ancient buildings of Roman Florentia.

Artist impression of Roman Florentia

I often daydream about the places I’ve travelled to, and Florence is certainly at the top of that list – the history, the art, the architecture, the food, and the surrounding Tuscan countryside are the stuff of dreams.

If you ever get the chance to visit Florence, or to go back, by all means, soak up the Medieval and Renaissance worlds to your heart’s content. Those are the reasons to go in the first place!

However, while you’re strolling the streets, enjoying your gelato from Festival del Gelato or any other gelateria there, take a few moments to think about where this magnificent city of art and culture came from.

Florence from Fiesole

The Etruscans had built on the hill, away from the river, but it was the Romans who set up camp here. And whether it was erected by Julius Caesar or not, or named after a fallen hero of Rome, the Florence of today owes its past to the Florentia of the ancient world.

The remains of Florentia may not be easily visible now, but they are there, in the shadows cast by ancient Rome.

Arrivederci e grazie!

Ciao from Firenze!

Ok, so that photo is a few years old 😉

Slavery in ancient Rome – A guest post by A. David Singh

Salvete readers and Romanophiles!

This week on Writing the Past, I’d like to welcome fellow author, A. David Singh, who has written a fantastic piece for us about slavery in ancient Rome.

You probably know that slavery was widespread in the Roman world, but what you might not know are the ins and outs of slaves’ lives.

Check out David’s post below for a brilliant introduction to this topic…

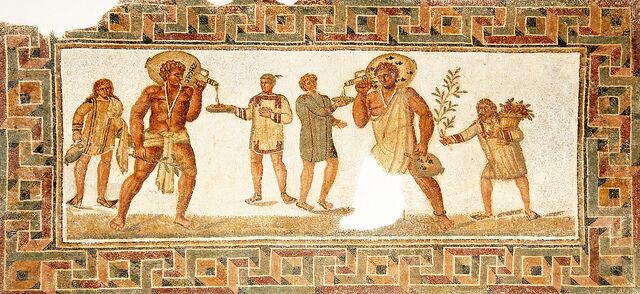

Slaves serving at a banquet – mosaic floor. Found in Dougga, Tunisia, 3rd century A.D. (Dennis Jarvis_Flickr)

In the first century A.D., over a million people lived in Rome — and a third of them were slaves.

Ancient Romans considered their households to be a microcosm of the state of Rome, and slaves were an integral part of their households. Slavery was such a key foundation of their society that if an ancient Roman were to time-travel to the present day, he would be surprised to see a society function just fine without slaves.

In addition to cooking, cleaning, and carrying loads within their master’s household or country estate, slaves served another important function — that of elevating the social status of their masters. This is much the same prestige that a champion race-horse confers upon its owner.

How did one become a slave?

Being born into slavery was the commonest way. Children born to a women slave automatically became slaves to her master.

Another way was by capturing enemies. As Rome waged wars far beyond its borders — in Europe, Asia and northern Africa — a steady supply of prisoners of war poured in, who, in lieu of their lives being spared, were sold to the slave-traders. During his Gallic campaigns, Julius Caesar is rumored to have captured over a million prisoners of war in Gaul and sold them into slavery.

Criminals too could be enslaved, but their masters had to be careful about their violent streak. Unwanted babies who were thrown into rubbish dumps outside the city, though technically free, could be picked up by slave dealers or surrogate parents who would sell them into slavery. A similar fate awaited children kidnapped by pirates and other shady elements of society.

Finally, free Roman citizens, if deep in debt, could be forced into slavery. Some of them voluntarily chose to become slaves to repay their debt. However, Roman citizens submitting to slavery was considered illegal.

Where were slaves sold in Rome?

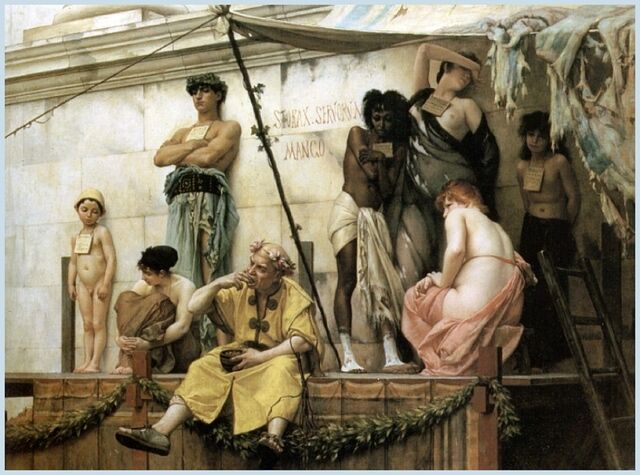

The slave market was commonly held behind the temple of Castor and Pollux, and also near the Pantheon. Men, women and children were displayed on raised platforms, just like fruit stands in a bazaar. They wore dejected looks, being resigned to their fates.

The slave trader adorned them with signboards around their necks with information like place of birth and other personal characteristics. It was a common spectacle to see signs like: Gaul, cook, specializes in making spicy fish and the use of Garum or Greek, ideal for teaching philosophy and reciting verses during parties.

Those who came to buy slaves found it in their interest to ensure that the slaves had no physical or mental defects. So, a thorough examination of their bodies was a common occurrence, and putting them on raised platforms helped to do just that.

A young male, 15 to 40 years old, cost 1,000 sesterces, while a female was priced at 800 sesterces. Much younger slaves or those older than 40 years went cheaper. Of course, prices would have been higher for slaves with special skills like reading and accounting.

The slave market had different days allocated for selling different types of slaves. There was a day for selling strong, muscular slaves meant for heavy labor. Another day for those specializing in trades like bakers, dancers and cooks. Boys and girls meant to work in houses and for banquets had their own day of sale, as did those with physical deformities.

What happened afterwards?

Once they started their lives of servitude, not all slaves had the same luck. The best deal that a slave could hope for was becoming a house slave to a kind master — even better, if the master was an important man in Rome. Moreover, there was also the possibility of being freed one day.

Then there was a class of slaves who worked in shops, under the command of an ex-slave. In addition to lugging heavy loads, they had to contend with the emotional baggage of their boss’ recently concluded life as a slave.

Those less fortunate were sold into miserable hovels of brothels, used pitilessly till they broke down or became useless. But a worse fate awaited those slaves who worked in country estates and mines. They lived in pathetic conditions with little food, frequent beatings, and were even locked in filthy prisons at night. It’s no wonder that they had very short life expectancies.

Wealthy Romans were not the only people to own slaves. The state of Rome had its own collection. These slaves were of another class — public slaves. They worked in public baths, food warehouses, or constructed roads and bridges, or worked in public administration offices. They helped in running the economy of Rome. Life was probably kinder to them than to their counterparts who worked in the mines and country estates.

The conditions for slaves were extreme during the Roman Republic. But it is believed that they eased later on. During the Empire, slaves could earn money, get married (informally) and have children. Killing of slaves was banned.

The Slave Market – oil painting by Gustave Boulanger, 1886 (Wikimedia Commons)

What were master-slave relationships like?

In rigid households, slaves were considered nothing more than objects that could talk and walk. They could be sold, rented, or replaced, just the way we do nowadays to our inanimate possessions. The master always decided the level of relationship permitted to their slaves. They could be friendly, or exploit their slaves, or in extreme circumstances even kill them.

On the other hand, if a slave killed his master, then all the other slaves in the household were slaughtered under the charge that they failed to protect their master from the rogue slave.

However, many masters considered slaves as human beings, worthy of moral behavior, and hence treated them with a degree of respect.

Each master had to balance how he treated slaves with the need to keep them working. Brutal treatments were rare because they would wear out the slaves.

Home-born slaves were most likely to remain loyal to their masters, considering him like their own father (which, in many cases he really was). However, barbarians captured from distant lands took some time to be broken into their new, reduced station in life.

Most often, masters incentivized slaves to work hard and stay loyal. Firstly, they rewarded hard work with generous rations of food and clothing. At times, even allowing them to have children, and occasionally organized sacrifices and holidays for them. Such acts of generosity went a long way in ensuring their slaves’ loyalty.

Secondly, slaves had clearly defined job roles, suitable to the their mental and physical attributes, like cooks, door-keepers, or food-servers. This division of labor generated accountability, as the slaves knew that they could be punished only for jobs that they were responsible for, and not for duties outside their job descriptions.

But the most important incentive for slaves to work honestly and with diligence was the possibility of gaining their freedom and becoming Roman citizens.

Manumission

Unlike the Greeks, the Romans took a liberal view of slavery, regularly incorporating slaves into their own society. Thus slavery was viewed as a temporary state, after which, if the slave had shown the right attitude, they could be set free and become a Roman citizen.

This process of leaving the shackles of slavery and becoming free men and women was called ‘manumission’.

If a master was happy with a slave’s services and felt him worthy of being free, the slave could be set free by appearing before a magistrate. Once the magistrate had confirmed that the slave was a free man, the master would often slap the slave, as a final insult, before he started his new life.

Often, a master would bequeath his slaves’ freedom in his will. This is how most slaves got their freedom. In rare cases, slaves could also buy their freedom, if they could raise enough coin — or get another freedman to buy their freedom.

Manumission was generally practiced in urban regions, where it was possible for slaves to form meaningful relationships with their masters and be in their good books. Those working in country estates or mines did not have direct contact with their masters, and were usually worked to death.

Relief showing manumission of a slave. Marble, 1st century B.C. Musèe Royal de Mariemont (Ad Meskens_Wikimedia Commons)