architecture

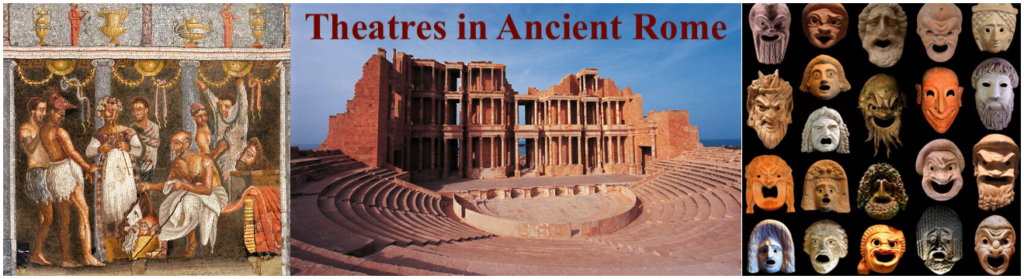

Theatres in Ancient Rome

Salvete, ancient history-lovers!

Welcome back to the blog and the first post of the New Year on Writing the Past!

Over the years, one of the main goals of this blog has been to share the research I have been doing, whether it is for a fiction work-in-progress, or a wish to share some added knowledge about the ancient world.

For the past few months, I’ve been deep into writing a new novel (a comedy!) set in ancient Rome which has taken me deep into the world of Roman theatre. Today, I would like to share a little snippet of the research that went into this new work of historical fiction.

One of the main questions I had when I set out on this latest project was around the physical structures of the Roman theatre. Of course, I knew about ancient Greek theatres, having visited several in my travels over the years. But what about Roman theatres? Did the Romans simply re-use Greek odea? Did the Romans build their own theatres and, if so, how did they differ from those built by the Greeks?

In this blog post, we’re going to be taking a brief look at theatres in ancient Rome and how they differed structurally from those of the Greeks.

The ancient theatre of Epidaurus

The ancient Greeks were, of course, the progenitors of drama and the theatre. When one thinks of ancient theatre, it’s difficult not to think first of an ancient Greek theatre such as the the magnificent, and still-used, example at ancient Epidaurus in the Peloponnese. Or even the beautiful, silent ruins of the great theatre of Argos. It is quite an experience to sit in the ancient seats and not feel some sort of communal awe from centuries past, looking out to the distant mountains or sea beyond the stage where ancient actors would have enacted stories of gods, goddesses, heroes, and the trials and tribulations of everyday people on their journey through this life.

The ancient Greek playwrights – Euripides, Sophocles, Aeschylus, Aristophanes and others – had a way delving deep into the heart of human emotion and experience and making people linger there so that they would, hopefully, come out of it a bit more enlightened. And in a setting such as those ancient theatres, it would be hard not to.

Having seen comedic and tragic plays performed while sitting with thousands of others beneath the stars is an experience I shall never forget.

But even if one is not moved by the words spoken by the actors, it is difficult not to marvel at the genius of the architecture that allows the audience at the top of the seats to hear a whispered word spoken from the centre of the orchestra.

Ancient theatres really are engineering wonders!

The ancient theatre of Argos, Peloponnese, Greece.

Of course, the men of the Tiber knew a good thing when they saw it, and so they eventually adopted drama and theatres while adding their own Roman flair.

But this took some time, and some convincing…

Drama and theatre first came to Rome through contact with the Greek cities to the south and the Etruscans to the north, who had regular contact with the Greeks. It might have been looked upon with suspicion by conservative Romans at first, but eventually, drama would take hold of the Roman people.

Etruscan Entertainers

In 364 B.C., the Roman Republic was hit by a plague, and in an effort to please the gods and entreat their aid, Rome vowed to hold theatrical festivals in their honour.

To do this, Etruscan actors were brought in and the rest is history. This considered by some to be the start of this new entertainment for the Roman public, an entertainment inspired by the Greek cities of southern Italy.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens

Plays were originally performed in Greek, but over time Latin playwrights emerged, such as Plautus, Terence, and others. Of course, there were tragedies and comedies in the beginning, but then folk and bawdy plays began to take hold, and the mimes and pantomimes became the most popular among ancient Romans.

To read more about the types of literature in ancient Rome, including drama, CLICK HERE.

We’ll discuss the different types of drama and its evolution in another post at a later date, suffice it to say that theatrical performances eventually became nearly as popular as chariot racing and gladiatorial combat in ancient Rome.

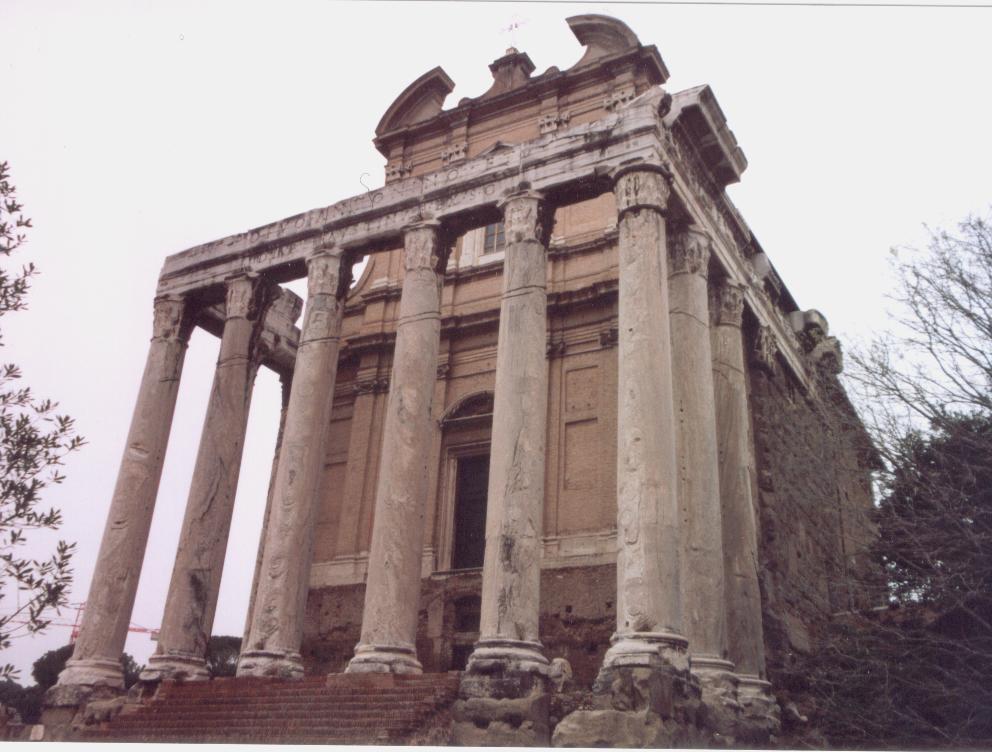

Temple of Antoninus and Faustina, Roman Forum. Play were sometimes performed on temple steps such as this.

There may have been theatres dotted all over territories which Rome had conquered early on, but in the city of Rome itself, there were no stone theatres at first, not like in Greek cities where a theatre was a given sign of civilization.

Early dramatic performances in ancient Rome were either performed on the steps of temples or on temporary wooden stages which were constructed in the Circus Maximus or Roman Forum for festivals. After the performances were finished, they were torn down.

Despite the popular appeal of drama in ancient Rome, conservative elements had a deep dislike of the theatre, viewing it as ‘too Greek’ and opposed to Roman values. The theatre – especially the mimes and pantomimes – were viewed as lewd, and this is a view that continued into the Christian era.

But, even among conservative Romans, it was hard to fight popular appeal, and the theatre was indeed growing in popularity.

Roman Re-enactors on the steps of a temple in Spain (photo: Turismo de Merida)

As we know, the Romans loved their games, or ludi, and by sponsoring these games, Roman magistrates had found a way to win the political favour – and hence, votes! – of the people.

Some examples of games which featured theatrical performances were the Ludi Apollinaris in honour of Apollo (July 6-13) and the Ludi Megalenses in honour of Cybele (April 4-10).

The building of theatres became a way to win the favour of the people. Unlike today when, sadly, theatre is viewed as something more for the elite or well-to-do, the theatre was, in ancient Rome, for people of all classes!

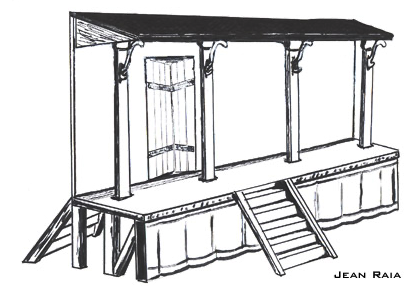

As mentioned, at first theatres in Rome were temporary and constructed of wood, but as time went on, even these wooden ones became more elaborate.

Artist Impression of temporary wooden stage of Roman period (image: Jean Raia)

In 58 B.C. Marcus Aemilius Scaurus built a wooden stage for performances, but this one had columns of African marble, as well as statues, glass, gold and fabrics to adorn it. The people loved it!

In 52/51 B.C. Gaius Scribonius Curio even built two moveable semi-circular theatres that could be pushed together to build an amphitheatre so that plays could be performed during the day and gladiatorial games viewed at night!

Eventually the time would come when Rome would receive its first stone theatre, despite conservative opposition, and this was given to the people by none other than Pompey the Great.

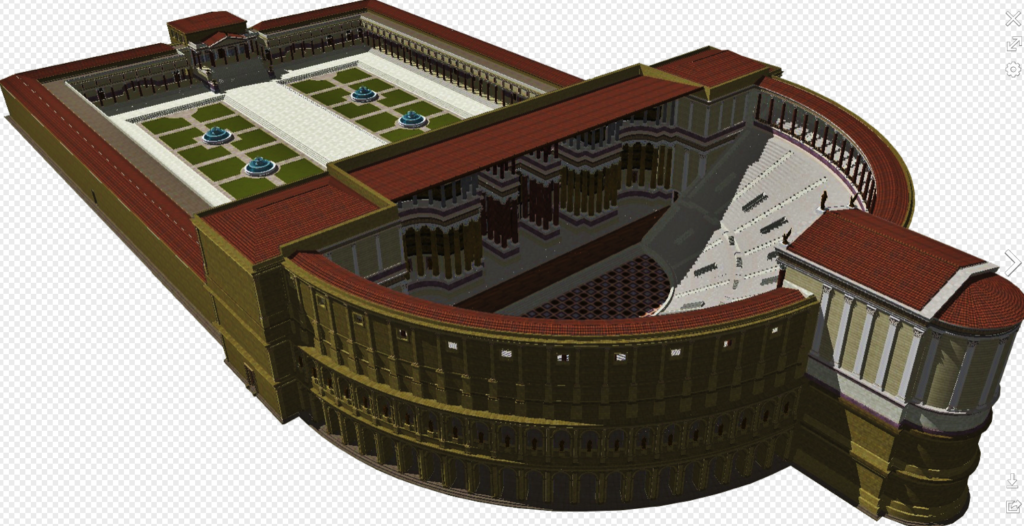

Reconstruction of the Theatre of Pompey in Rome with attached gardens and temple above the theatre seating.

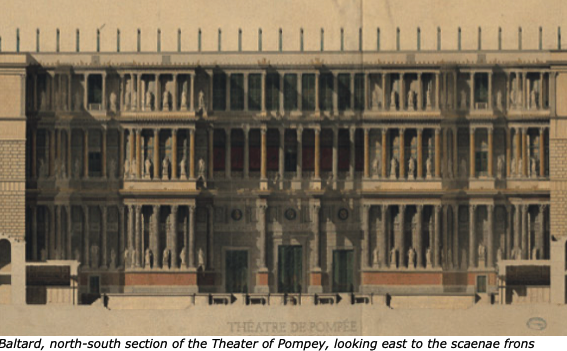

From 61-55 B.C., Pompey built a magnificent stone theatre for Rome, and he appears to have used his general’s wiles to get it done in a way that tricked conservative dictates. You see, this was not only a theatre, but also a temple complex dedicated to the goddess Venus herself.

Atop the great theatre of Pompey, resting above and behind the seats of the auditorium, was a magnificent temple of Venus. The argument was, it seems, that the theatre itself was simply the substructure of the temple, the ‘real’ purpose of the construction. The gods were now present in the theatre, and no one would have dared to tear it down!

The theatre of Pompey is now, perhaps sadly, known as the place where Julius Caesar was murdered (the senate was meeting there at the time), but more importantly, it was the beginning of a greater acceptance of theatre in the city of Rome.

Indeed, after the accession of Augustus, one of his supporters, one Lucius Cornelius Balbus, built a second stone theatre in Rome, on the Campus Martius, known today as the Theatre of Balbus. It was also roughly about the same time that the Theatre of Marcellus was also dedicated and ready for use by the time of the ludi saeculares of 17 B.C.

Rome now had three large, permanent theatres.

Model of the Theatre of Balbus

These permanent Roman theatres, however, were more than places to stage dramatic performances. They were also meeting places that incorporated religious elements. There were temples, and gardens and courtyards where people could stroll between acts, or meet outside of performances. They became part of the fabric of the city of ancient Rome.

But what were the structural differences between ancient Greek and Roman theatres?

It is impossible to deny the simple beauty of ancient Greek theatres, and the brilliance of their acoustic design. It is truly astounding to sit at the top of the seats and hear someone drop a coin or light a match in the middle of the orchestra!

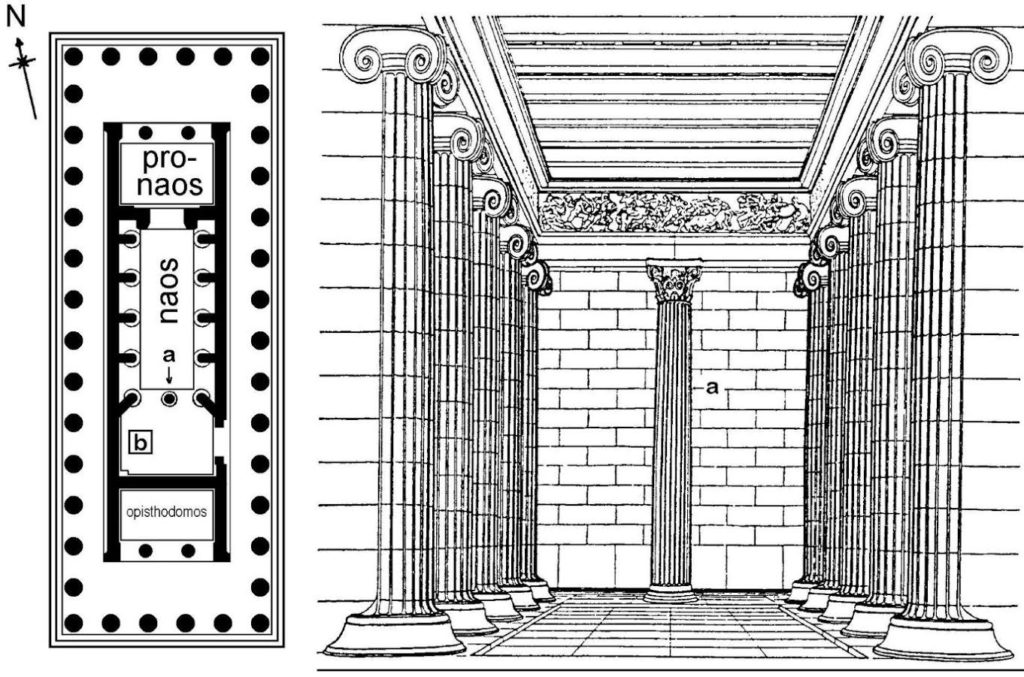

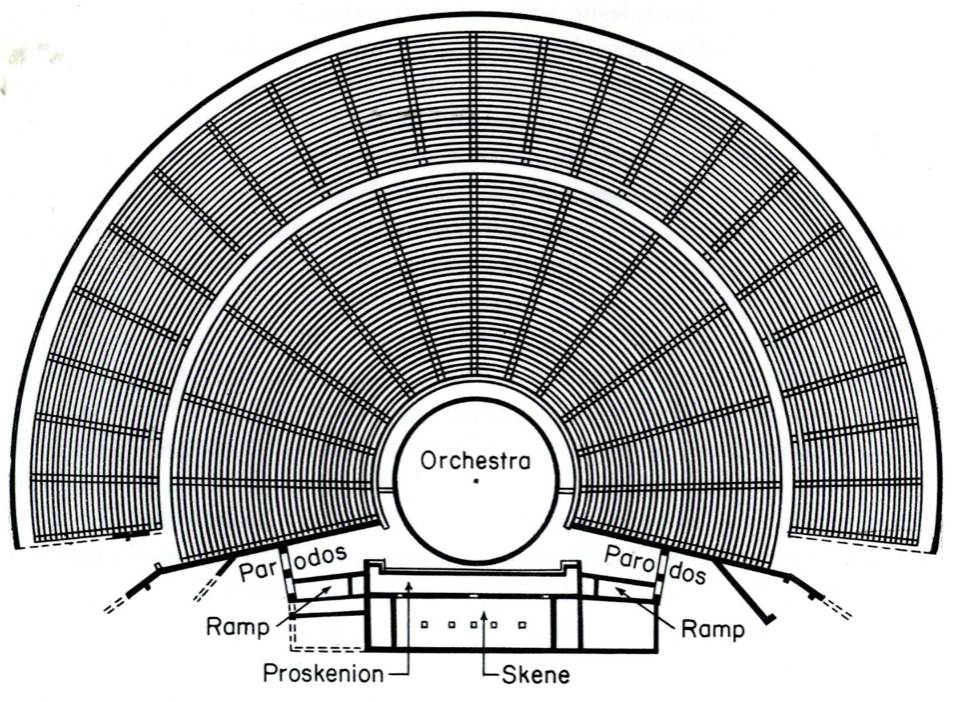

Plan of an Ancient Greek Theatre

Roman theatres were of course, based on Greek designs. Even the Romans could not deny the acoustic uses!

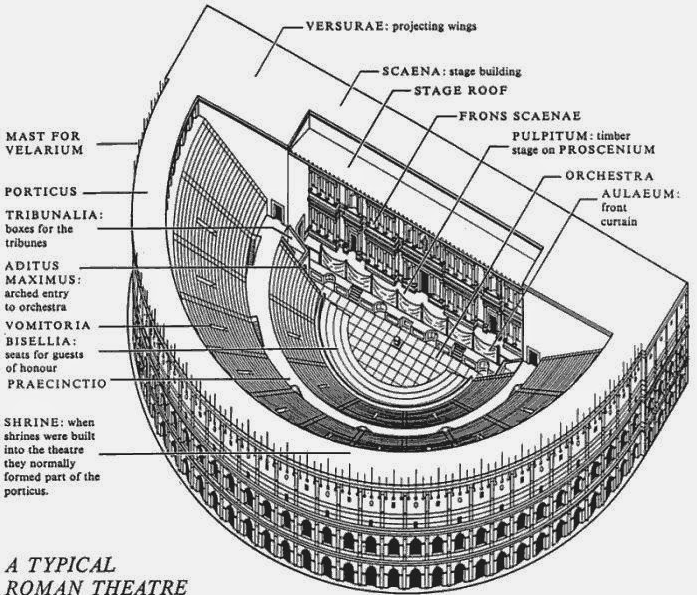

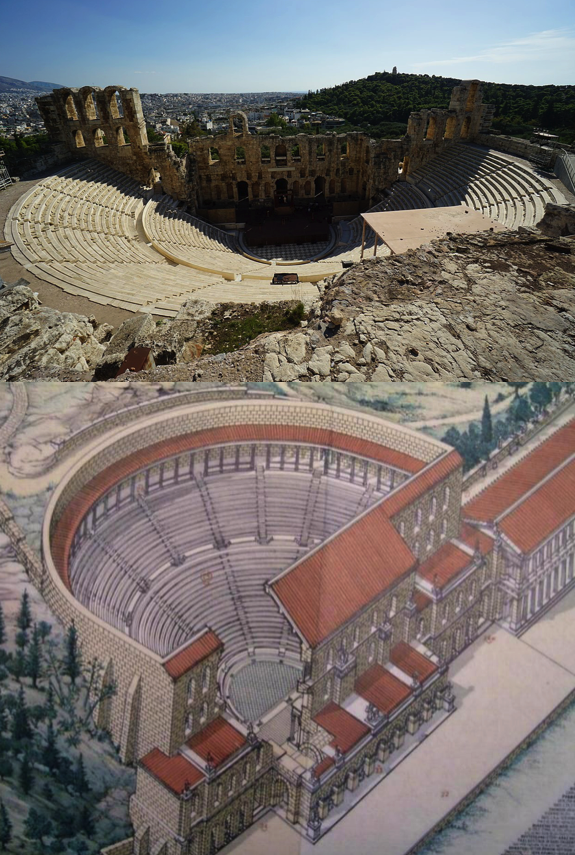

But whereas Greek theatres, or odea, were normally built into a hillside and had round orchestras where the performance took place, Roman theatres were more often stand-alone structures with semi-circular orchestras where seating was reserved for high-ranking officials, senators, or members of the imperial family. Roman theatres were constructed with solid masonry or vaults that supported the curved or sloping auditorium seats, or cavea. This design sometimes included a colonnaded gallery around the outside that gave easier access to the tiers of seats.

Plan of a Typical Roman Theatre

Another innovation given to the theatre by the Romans was the inclusion of a curtain before the stage. Today, it is hard not to think of a curtain in a theatre, and we owe this to the Romans. The difference was that where today the curtain hangs from above, in a Roman theatre, the curtain, or aulaeum as it was known, retracted into a pit in the floor before the stage at the beginning of the performance, and rose out of it at the end.

The most noticeable difference between Greek and Roman theatres, however, was the Roman scaena.

In an ancient Greek theatre, initially, the chorus and actors performed on the round orchestra, but later on, a raised stage, or proskenion, was incorporated. At the back of this stage, they began to build a one or two-story backdrop known as a skene, the ‘scene’ before which the action took place, and behind which the actors could change. The Greek skene did not obstruct the view beyond the theatre, however, but rather just provided the ornate backdrop.

The Roman scaena, however, was much more substantial, for it more or less enclosed theatre completely and provided a full divider between the audience and backstage.

Scaenae frons in Roman theatres had three or five doors flanked by columns and statues in niches. The scaena and its doors could provide the setting for a street scene, houses, palaces etc., and sometimes it was even sectioned off with smaller curtains called siparia as needed.

The Roman-era theatre of Herodes Atticus, Athens

The Roman scaena also rose to the full height of the theatre itself, either level with the rear seats of the auditorium, or even higher. There was also a wooden roof above the stage of Roman theatres that also acted as a sounding board.

It wasn’t just the actors who were protected from above either, for in some Roman theatres there could also be an awning above the auditorium known as a velarium, to shield the viewers from sun and rain. Roman theatres also had covered porticoes where audience members could go between performances.

The Romans did like their comfort!

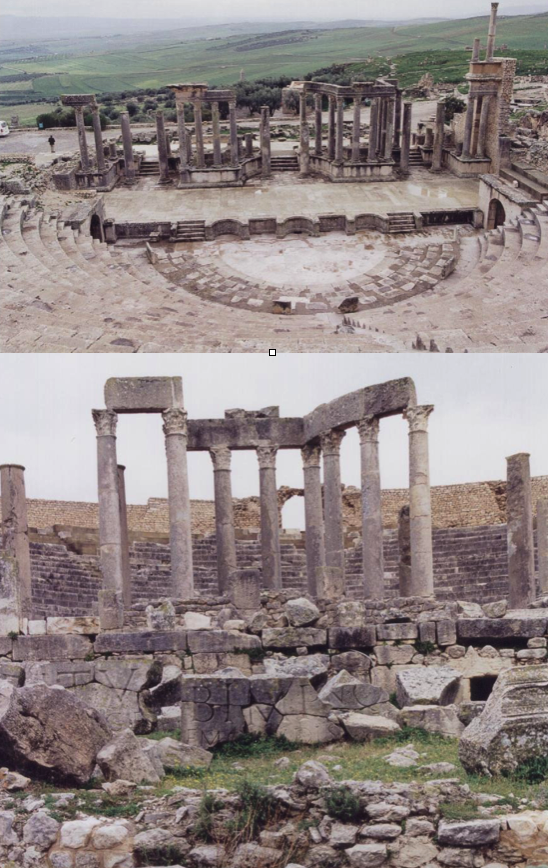

The Roman theatre in Thugga, Tunisia.

Were Roman theatres built across the Empire once Rome had made its own innovations in theatrical architecture?

Well, it seems the Romans did make adjustments to some Greek theatres by adding their own scaenae. However, especially in the Hellenistic east, Greek odea continued to be used, only just for more refined performances of music and poetry recitations rather than for populist mimes and pantomimes.

Romans continued to use the odeon design when called for, but sometimes with the addition of a roof. This type of smaller, enclosed and roofed theatre was known as a theatrum tectum. An example of this is the one built in Pompeii in 79 B.C.

Aerial view of theatres of Pompeii. Note the theatrum tectum on bottom right which would have been fully enclosed.

When it comes to theatres and theatrical performance, whatever the genre, the Greeks and Romans did have this in common: theatre was extremely popular with the people and important for the social life of the community, be it in the cultured metropolises of the Empire, or on the distant borders, far from the beating heart of Rome.

The Greeks may have invented theatres, but some might argue that it was the Romans who perfected them.

Roman Theatre of Aspendos, in modern Turkey, is one of the most intact Roman theatres in the world. (Wikimedia Commons)

More posts about Roman theatre are coming soon, but if you are interested, you can check out my previous posts about my visits to the theatres of ancient Argos, and ancient Epidaurus.

Be sure to also check out the post on Literature in Ancient Rome which includes a short discussion of Roman drama.

Thank you for reading!

Peloponnesian Eyrie – The Temple of Apollo Epikourios

Once it a while, I come across a site that strikes me as so magnificent and mysterious that I wonder why I didn’t know about it before, why it’s not spoken of by everyone with an inclination to ancient history.

If you’ve been reading my blogs you’ll know that I love to travel and have done so quite a bit in Greece. A few years ago, I was touring some of the major sites with friends and family – Delphi, Mycenae, Olympia etc. The biggies.

After Olympia, we drove back into the mountains of the Peloponnese. It was hot and bright, and the cicadas were whirring louder than I had ever heard before. As I was navigating a particularly treacherous series of mountain switchbacks, my father-in-law said that we should go south to Bassae.

“Bassae?” I said. “What’s there?”

“Some ruins,” he answered. “There is a temple of Apollo Epikourios.”

“Apollo Epi-what?” I half-answered, too focussed on the road to pronounce this new, strange word.

Admittedly my first thought was of Apicius and food – no matter that the Roman gourmet was about a six hundred or so years off. I was also starving at that moment!

So we turned south, into the teeth of even larger mountains.

Apollo Epikourios means ‘Apollo the Succourer’ or ‘Apollo the Helper’.

The epithet refers to Apollo’s role as a god of healing.

In the mid-seventh century B.C., Spartan warriors and plague came to the people of Phigaleia who were living in these high mountains. Many offerings in the form of weapons were found on site indicating that originally, in this place, Apollo was worshipped as a martial god. However, after escaping Spartan aggression and the plague of later years, Apollo became a ‘succourer’ or helper to the Phigalians.

In gratitude, the Phigalians commissioned the architect Ictinus to build the temple at Bassae.

This was no small thing. In Classical Greece, Ictinus was an A-list architect – he was one of the architects of the Parthenon and the great Temple of Mysteries at Eleusis.

In the second century A.D. Pausanias visited Bassae and the temple there:

“Phigalia is surrounded by mountains, on the left by Mount Cotilius, while on the right it is sheltered by Mount Elaius. Mount Cotilius is distant about forty furlongs from the city: on it is a place called Bassae, and the temple of Apollo the Succourer, built of stone, roof and all. Of all the temples in the Peloponnese, next to the one at Tegea, this may be placed first for the beauty of the stone and the symmetry of its proportions. Apollo got the name of Succourer for the succour he gave in time of plague, just as at Athens he received the surname of Averter of Evil for delivering Athens also from the plague. It was at the time of the war between the Peloponnesians and the Athenians that he delivered the Phigalians also, and at no other time: This is proved by his two surnames, which mean much the same thing, as well by the fact that Ictinus, the architect of the temple at Phigalia, was a contemporary of Pericles, and built for the Athenians the Parthenon, as it is called.” (Pausanias)

When most tourists visit the Peloponnese today, they focus on sites like Mycenae, Epidaurus, ancient Corinth, and of course, Olympia. Why wouldn’t folks head for these places? They are magnificent sites that are all worth visiting – more than once.

However, if you are more adventurous and enjoy heading off the beaten path, the Peloponnese holds some hidden treasures that are not always prominently featured in guidebooks or on tour itineraries.

Bassae, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of those special, unsung places. Academics know about it but few tourists make it there. In fact, due to its remote location, it lay mostly forgotten until the early nineteenth century.

Our car whined up the steep mountain, higher and higher, the sunlight blinding. I felt like Icarus for a moment, driving up and up.

We finally levelled out and our eyes were met by a giant, white…tent.

“This is weird,” I remembered saying. I had no idea what lay beneath the white, sail barge structure.

We paid our minimal entry fee to the lady in the wooden site booth; she sat smoking and sipping an hours-old café frappé.

The mountain top was rocky and desolate, patched with hardy olive trees and shrubs. We made our way up the rocky path to the tent and stepped beneath the awning.

I couldn’t believe my eyes.

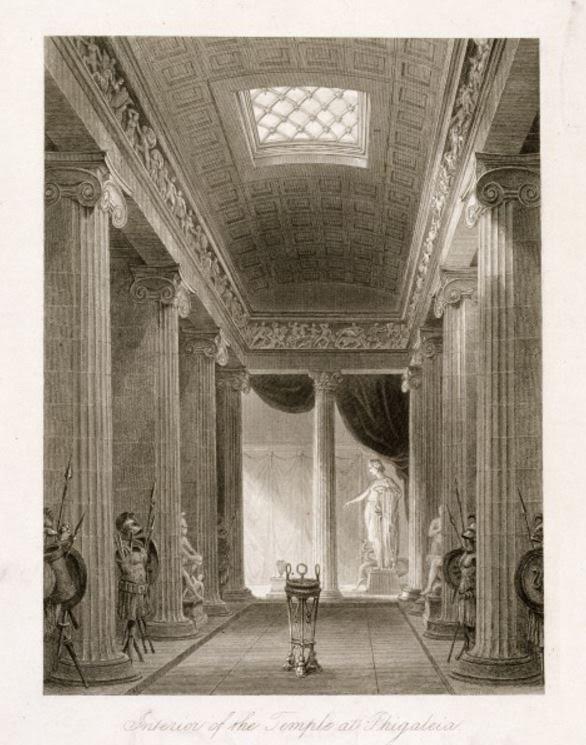

Up there, at what felt like the top of the world, was a magnificent stone temple, one of the most complete temples I had ever seen. The stone was cracked in many places, pounded by the elements for centuries in its eyrie.

But it was intact, columns and walls, foundations. A few stray rays of sunlight made their way into the shaded sanctum to illuminate the cella. We were the only visitors on site, and the main sense that invaded my person was pure awe.

Bassae’s Temple of Apollo is a particularly important specimen, and not just because of the architect. It contained the earliest known example of a Corinthian capital which was displayed in the middle of the naos which was lined with Ionic columns. However, on the outside of the temple, the strength and support of the structure is provided by strong Doric columns, fifteen on each long side and six on the ends.

One of the things that make this temple unique is the incorporation of all three of the classical orders of columns. Also, the interior of the cella was ornamented with a series of beautifully detailed friezes of the Amazonomachy (Battle of the Amazons) and the Battle Centaurs and Lapiths.

You can see the Bassae Friezes at the British Museum where they are on display, far from their home at the top of that lonely mountain.

I think I was in such awed shock the first time that I didn’t quite realize what I was looking at.

Some places do that to you. The power of the place and setting can quite overwhelm the academic eye.

After wandering around the temple for a time, we went back outside into the sun to look at the surrounding countryside. These were some of the highest mountains in the Peloponnese and they stretched out in all directions. It is a quiet, contemplative atmosphere.

Outside the cicadas were louder than ever, but it is a sound I have come to associate with peace. The air was hot but dry and tinged with wild thyme that must once have been laid upon Apollo’s altar by the Phigalians.

We stood in the sun and looked to Mount Kotilon where the map indicated that there was a Temple to Aphrodite and another to Artemis Orthasia, the ‘Protector of Small Children’.

These mountains are a place for gods.

I hope, one day, to return to Bassae. I want to circle the Temple of Apollo Epikourios and to remember the Phigalians who thanked him for his aid by building him this magnificent sanctuary in the sky.

* A useful source on the temple of Apollo Epikourios is:

The Temple of Apollo Epikourios: A Journey Through Time and Space published by the Greek Ministry of Culture Committee for the Preservation of the Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassai

Ancient Everyday – Time for a Bath

Showering, bathing and generally keeping clean is something that we take for granted today. For most people, washing is part of the daily routine.

If you look at the Middle Ages, this was not the case. In fact, medieval people were pretty filthy. This isn’t surprising as bathing was considered a sin by many.

This wasn’t the case for ancient Romans, thank the gods.

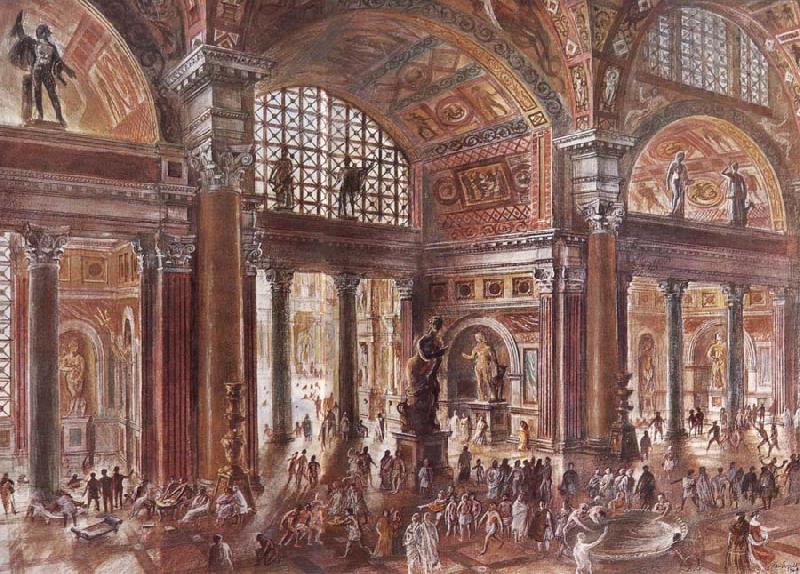

As we do today, the Romans bathed and washed regularly, and as with going to the toilet, bathing was yet another very social activity for Romans.

Throughout the Roman Empire, public and private baths were common, owing something to the situating of bath houses over hot springs, and their ingenious use of aqueducts which brought water into the cities over great distances.

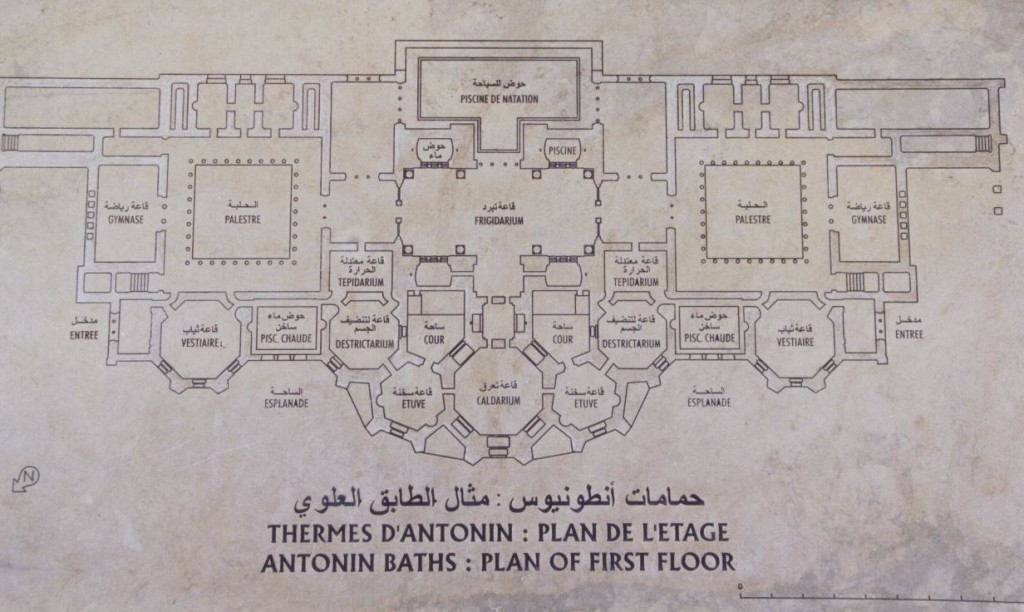

Baths and bathing complexes, of course, varied widely in size and the level of sophistication, whether the small pools and tubs of private balneae, or the massive imperial complexes called thermae. Whatever the size, there were some common attributes to most public baths across the Empire.

The Apodyterium

This was a sort of changing room where visitors to the baths would undress and leave their clothes in niches in the walls, not unlike today. Slaves were in attendance to give out towels and take care of your items. However, not unlike today, theft was common in the apodyterium, so wealthier patrons brought their slaves along to carry their possessions for them.

The Palaestra

The palaestra was the workout area where some patrons would exert themselves before going into the baths themselves. Just as people hit the gym today, so the Romans exercised on the sands of the palaestra by wrestling, boxing, lifting stone or lead weights, and other activities. The scene here would have been one of competition, of grunting, and sweating. It could get pretty loud, as attested to by the Roman Seneca:

“I live over a public bath-house. Just imagine every kind of annoying noise! The sturdy gentleman does his exercise with lead weights; when he is working hard (or pretending to) I can hear him grunt; when he breathes out, I can hear him panting in high pitched tones. Or I might notice some lazy fellow, content with a cheap rub-down, and hear the blows of the hand slapping his shoulders. The sound varies, depending on whether the massager hits with a flat or hollow hand. To all of this, you can add the arrest of the occasional pickpocket; there’s also the racket made by the man who loves to hear his own voice in the bath or the chap who dives in with a lot of noise and splashing.” (Seneca in AD 50)

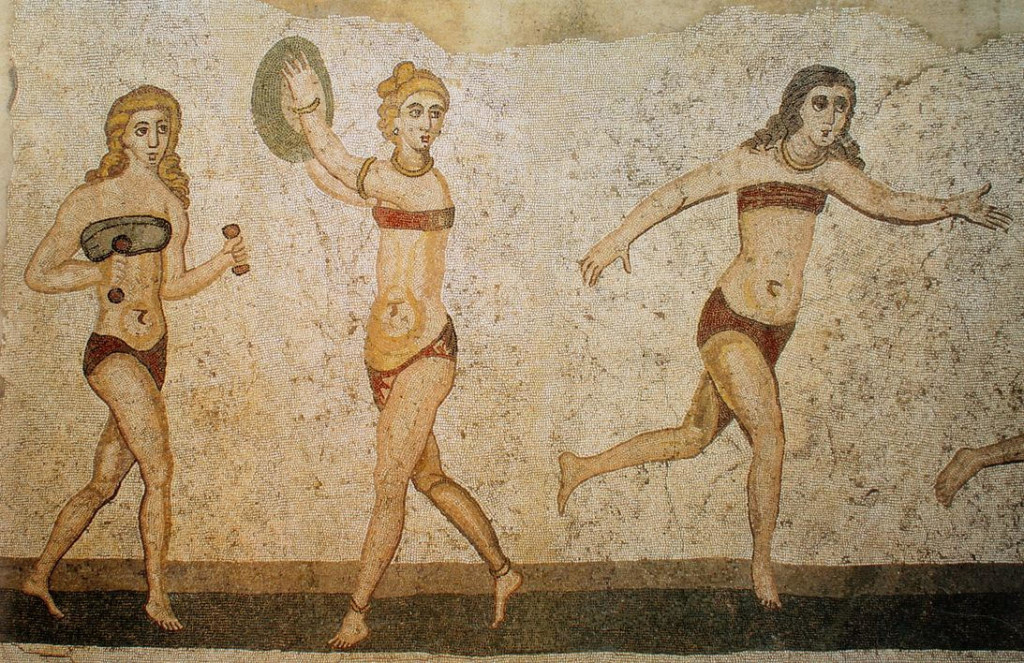

But the palaestra was not just for men. In ancient Rome, women too were permitted to exercise and stay fit. One famous mosaic shows a group of women engaged in exercise on the palaestra floor, though this was probably done at a different time, or in a separate area from the men.

The Tepidarium

After the exertions of the palaestra, patrons would then move to the first room of the baths proper, the tepidarium. As the name implies, this was the ‘warm’ room where one could begin to heat up and start sweating. In some cases, the tepidarium had a warm water bath in which bathers could submerse themselves, but in other instances, it was just a room of warm air, thanks to the underground, and in-wall heating from the system of hypocausts that were used to heat the baths.

The tepidarium was often highly ornate too. Men and women could lounge and talk business, gossip or anything else while being rubbed down with oils which the Romans used instead of soap. Once they were warm enough, and the oils had started to go to work on their pores, bathers moved to the next room.

The Caldarium

The caldarium was the hottest room in the bath complex, located as it was directly above the hypocaust furnace. This was the equivalent of the modern sauna where patrons would be more still, sweat, and scrape the mixture of oil and dirt from their skin with a tool called a strigil.

The caldarium had a basin with cold water for patrons to wet themselves with, but also a hot pool if they wanted to soak some more. The heat from the caldarium is what brought the dirt to the surface and aided with the cleaning of their bodies in concert with the oil that was rubbed on.

The Frigidarium

After the tepidarium and caldarium, it was time to close the pores and revive, and what better way to do this than by jumping into a cold pool of water.

Welcome to the frigidarium! One can imagine the echo of people’s squeals as they landed in the cold water, the shock running through them in a great wake-up call. Some of the larger bath complexes would also have included a swimming pool at this stage, in which patrons could swim a few laps.

The frigidarium was not a room patrons would spend too much time in. Who would want to when the next step is so enjoyable?

Massages, Food, and more Socializing

After having made his/her way through the various rooms of the bathing complex, many Romans would opt to get a massage. Either they had their own slaves oil them again and work away at their muscles, or they would have one of the bathing complex’s massage slaves work on them.

What better way to work out the knots owed to debates in the Senate house, fights on the battlefield, haggling in the imperial fora or other activities than to have fragrant oils massaged into your newly cleaned skin.

I tell you, the Romans knew what they were doing with this ancient toilette ritual! I’m relaxed just thinking about it.

After the massage, and dressing again in the apodyterium, some of the larger complexes had tabernae attached where patrons could go and eat, have a drink, gamble a bit at games, and most importantly, socialize.

That’s the interesting thing about public baths in the Roman Empire; they weren’t just facilities intended to curb public health issues by keeping the populace clean and hygienic, they were also the community centres, or community hubs, of the ancient world.

They were a bit of an equalizer too. In the Colosseum or Circus Maximus, the rich might have had the better seats with cushions, but in the thermae of the Empire, when naked, everyone was standing on equal footing.

So, next time you visit your, gym, local pool, or community centre, remember that you are participating in a highly social activity, owed mainly to the ingenuity of the Romans.

Thank you for reading.

For a bit more information, check out the video below from the series What the Romans Did for Us, with Adam Hart Davis. In this episode, he looks at Roman baths among other things related to Roman luxury!