As I write this, a lot of my North American readers are getting buried in snow. It’s definitely winter!

So, I thought that this week it might be nice to counter the cold with a post about a site visit on one of the hottest days I experienced last summer in Greece.

I’m talking about my visit to the ancient theatre of Argos.

Until my first visit to the Peloponnese years ago, my only knowledge of Argos came from the movie, Clash of the Titans.

I can hear Harry Hamlin saying it now – “I am Perseus, heir to the kingdom of Argos.”

Harry Hamlin as Perseus, in Clash of the Titans

I loved that movie, so whenever I heard of Argos I pictured a city punished by Zeus for Acrisius’ blasphemy, turned to ruin by an earthquake and tidal wave caused by the Kraken.

Clash of the Titans had a huge impact on my imagination. Great storytelling!

Despite that, for years I had driven past Argos (an easy place to get lost in!), and seen the signs to the ancient theatre, but never stopped to explore.

It took some research for Heart of Fire to make me plan a trip to the archaeological site, and I’m so glad that I did!

On a day when the temperature soared slightly over 40 degrees Celsius, we set out from where we were staying in the southern Argolid peninsula, over the mountain switchbacks, and along the road from ancient Epidaurus to Nauplio. From Nauplio and the shadow of the Palamidi castle, our car whined along, past the ancient citadel of Tiryns, and then on to the city of Argos at the top of the Argolic Gulf.

The East Galaria of Tiryns

Once in the city, we promptly got lost.

No matter how many signs we saw for the ancient theatre, it seemed that we kept missing one important turn, and so we found ourselves in the farmers’ fields to the south of the city, among irrigation canals and orange groves.

A friendly Russian mechanic finally gave us some convoluted instructions, in Greek, with a lot of pointing, and eventually we found our way there.

We parked our car in the shade of a side street, alongside the ancient agora, crossed the road, and checked in at the entrance.

Due to funding restrictions, there were no site plans available at the time, but that was all right as the person working there said there were placards around the site.

The best part was that we had the entire archaeological site to ourselves!

Street leading to the ancient theatre

Before I get into the site visit itself, I would be remiss if I did not touch on the history of Argos.

Argos is believed to be the first town of any sort in Greece, or the surrounding geographical regions. It has been inhabited since the prehistoric age. It was a great centre during the Mycenaean age, along with Mycenae itself, and Tiryns nearby.

It its rise to power, Argos assimilated some of its smaller neighbours such as Tiryns, Mycenae, and Nemea, site of the Nemean Games. Argos was one of the foremost cities of Greece during the Classical period, as well as during the Hellenistic and Roman eras, until about A.D. 395 when it went into decline.

It was nearer to the Argonic gulf in ancient times, just as Tiryns was, but due to the silting up of the land, it now lies a short distance to the north of the seashore.

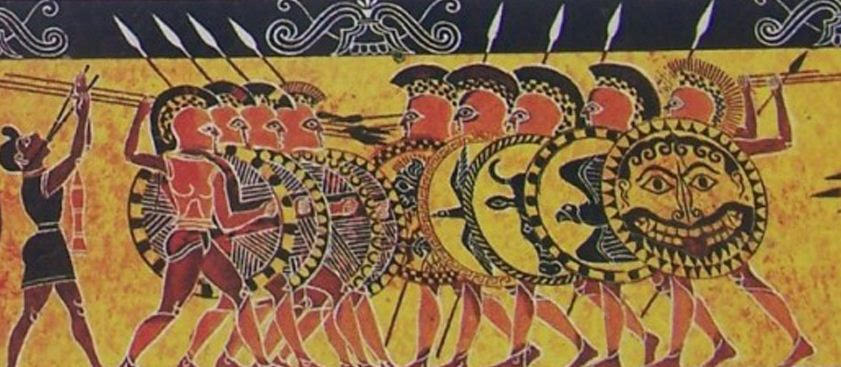

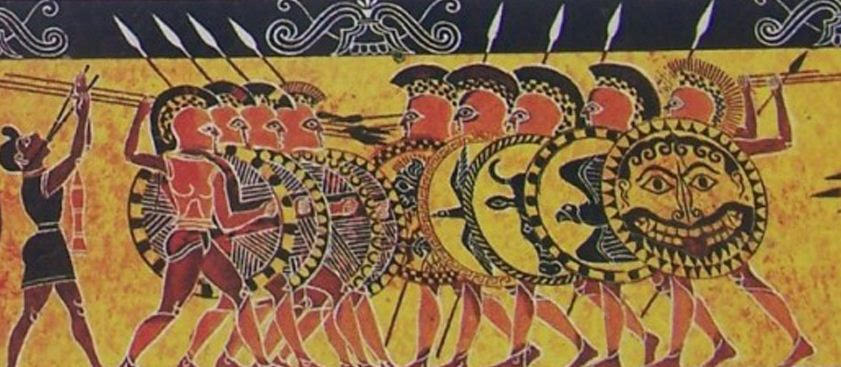

The peak of Argos’ power was said to have been in the 7th century B.C. during the reign of King Pheidon, the latter credited by some with the development of hoplite battle tactics in the Peloponnese.

Ancient Greek Hoplites in Battle

From the 7th to 5th centuries B.C., Argos came into conflict with that mighty martial power to the south, Sparta. During that time, the two city states fought for domination of the Argolid peninsula.

During the Persian wars, Argos decided not to fight the Persians alongside their fellow Greeks, and so became a bit of an outcast. Then, during the Peloponnesian War, it was a somewhat ineffective ally of Athens against their old rival, Sparta.

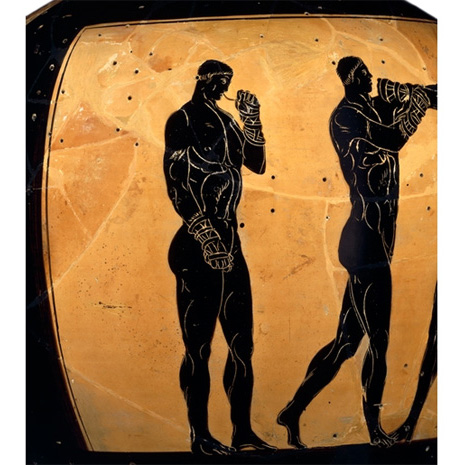

But Argos thrived during the Roman period too. In addition to being a centre for pottery production and the tanning of leather, Argos was a leader in bronze work. It was here that a noted school of bronze sculpting was established.

The Antikythera Youth – Possibly from an Argive School

When that famous philhellene emperor, Hadrian, came into power, he showed this ancient Greek city much favour, and, among several building projects in Argos, he gave the city an aqueduct and baths, or thermae.

I didn’t actually know what to expect from the site of the theatre in Argos when we parked our car. After all, I’d already been to Epidaurus, and that is pretty tough to match.

However, when we passed through the pine-shaded gates into the blinding light of the site itself, I knew it was going to be fantastic.

As you step down the stairs into the archaeological site, you are staring directly down an ancient street with walls rising up on either side in the faded white, grey and red of antiquity.

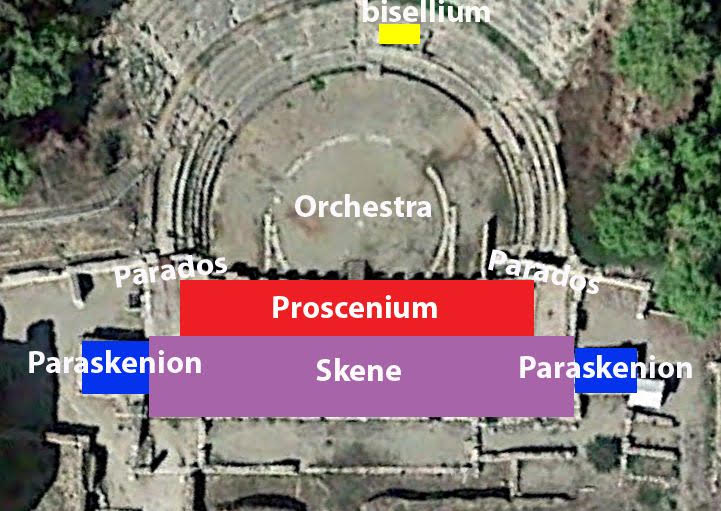

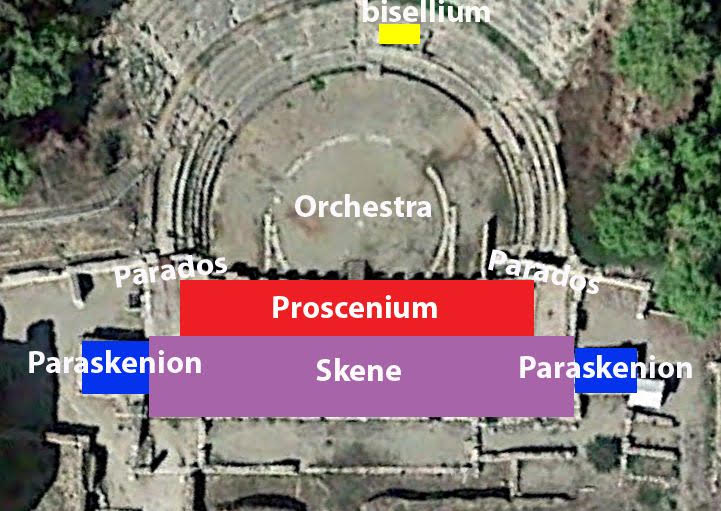

Aerial view of theatre (Wikimedia Commons)

The sun beat down on us with an intensity I’ve seldom experienced. The cicadas even sounded tired, their little hearts (if they have one?) probably near to bursting for all their song. We stopped here and there to look at some chipped and worn ornamentation, the gravel of the path crunching beneath our feet, sending lizards scampering into the ancient cracks and crevices.

I tried to imagine what the place would have looked like in its golden age, the walls and buildings of the neighbouring baths and other buildings rising high above the street level, perhaps some torches jutting out from the walls to light the way as the crowds were funneled into the theatre itself.

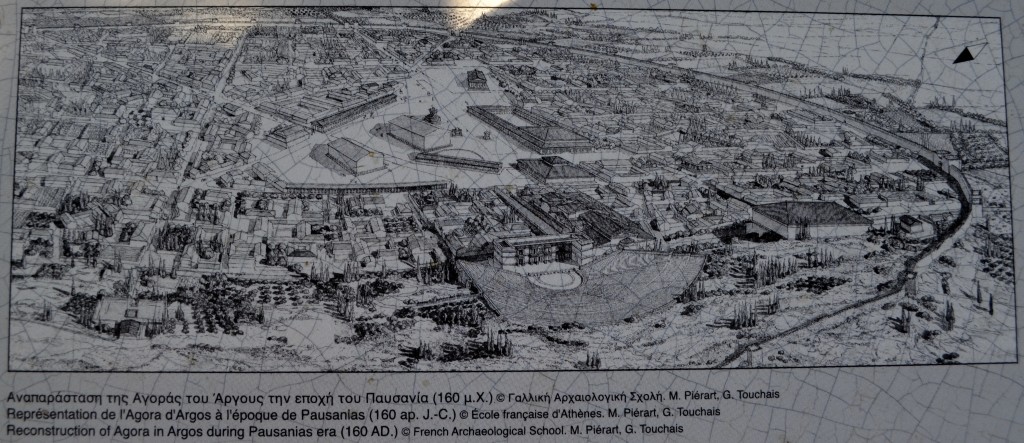

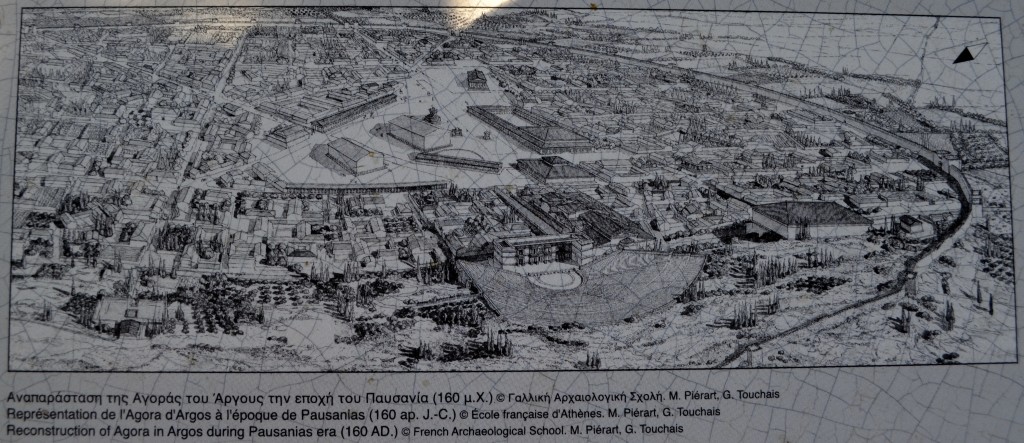

Site placard showing an artistic representation of ancient Argos with the theatre in the foreground

The theatre of Argos is a beautiful monster.

It was the largest theatre in ancient Greece, with a seating capacity of 20,000 spectators!

From a distance, it looks like any other theatre, but when you are up close and personal with it, you feel like a fly on the back of the Cretan Bull.

It has 81 rows of seats that rise up steeply from the round orchestra, one of only two such orchestras in ancient Greece, the other being at Epidaurus. The amazing thing about the theatre of Argos is that it’s carved directly into the rock of the Larisa which overlooks the city of Argos.

View from the orchestra

Behind the orchestra are the proscenion and scene, buildings that served as the stage and backdrop. I stood on the stage overlooking the orchestra and just took it all in.

What a sight!

The present theatre was built in the 3rd century B.C. and was used to host the musical and dramatic contests of the Nemean Games in honour of Hera, the patron goddess of this ancient city.

Once I had taken in the view from below, I began to walk up to the top of the seats.

I really started to cook here, the sun beating down on the stone increasing in intensity. But I couldn’t resist going to the top. It is actually quite steep, and the seating is nowhere near in as good a condition as Epidaurus.

However, it is well worth the trek, for when you reach the top, the view is amazing.

View of Argos from top row of the theatre. See the ancient Agora across the street where there is a clump of cypress trees to the right.

From the top of the theatre, with pine and towering cypress trees flanking me, I stared down the rows of seats to the stage, beyond to the ancient agora of Argos, just across the street, and the into the distance over the modern town to see the brilliant blue of the Argolic Gulf, and the mound of ancient Tiryns, just visible through the heat haze, like a thing out of legend.

I don’t remember how long I stood there, but it wasn’t until my arms started to sizzle that I thought perhaps I should head back to my party waiting in the shade of a pine tree at the bottom.

The site, apparently, was closing, and so I had a quick look at the remains of the sanctuary of Aphrodite to the right of the theatre, where a smaller Odeon was located, and then the Roman baths opposite.

The Roman baths next to the theatre

The ruins of the latter are worth a look too, and you can see marble floor and wall panels, the remains of columns, and some of the rooms of the Roman thermae. You can imagine the water dripping as you walk through there, the sound of conversation, the slap of masseurs’ hands on the backs of their clients. Just be careful where you walk, for snakes hide the shady corners, and there are some big drops if you spend more time looking through your camera lens than you should.

Column remains inside the ruins of the bath complex

Before leaving the site behind, I had to do one last thing: test the acoustics of the theatre.

Since we had the place to ourselves, I didn’t quite mind doing so. It’s a little difficult to hear the echo of my voice in this video, but, even though the theatre is ruined, and the lines broken in many spots, you can just hear how my voice travels up to the top when I turn to face the theatre. The acoustics of this place blew me away.

When I started talking in the direction of the seats, it was like I was holding a megaphone. I could hear my voice travelling up the rows of seats all the way to the top to disappear into the wild growth beyond.

If my untrained voice projected so well in that place, I can imagine what a trained actor’s would do.

With the site manager waving to us that it was time to go, I reluctantly turned my back on this ancient marvel, and walked back up the street.

Before exiting, I turned for one last glimpse of the theatre, grateful that we had taken the time to stop.

The ancient agora of Argos – across the street from the theatre

As we were leaving, we asked the site manager if we could visit the agora across the street, but he shook his head and told us that, due to budget cuts, all the sites were closing for the day. It was only 2:00 pm. He also told us that he had just heard Greece was going to have to sell some of its archaeological sites due to pressure from creditors.

I certainly hoped that was not true, for it would be a tragedy if the country lost control and care of such magnificent sites at the ancient theatre of Argos.

We thanked him, wished him well, and told him we would definitely be back to see the agora on another trip.

I was happy we visited, not only for the chance to see the site, but also to fuel the story for Heart of Fire, one of the protagonists of the story being an Argive mercenary. I needed to get a sense of the place where he grew up, the place he had left behind.

And I did.

Back in the car, we found the road to Nauplio once more and headed there for a stop at one of the seaside cafes and gelato at our favourite gelateria, Antica Gelateria di Roma.

Antica Gelateria di Roma

After all, it’s isn’t only archaeological sites that warrant a return visit. Especially when it’s over 40 degrees!

Thank you for reading.